Abstract

Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase, NDU) and complex IV (cytochrome-c-oxidase, COX) of the mitochondrial electron transport chain have been implicated in the pathophysiology of major psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder (BD), and schizophrenia (SZ), as well as in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease (AD) and Parkinson disease (PD). We conducted meta-analyses comparing complex I and IV in each disorder MDD, BD, SZ, AD, and PD, as well as in normal aging. The electronic databases Pubmed, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and Google Scholar, were searched for studies published between 1980 and 2018. Of 2049 screened studies, 125 articles were eligible for the meta-analyses. Complex I and IV were assessed in peripheral blood, muscle biopsy, or postmortem brain at the level of enzyme activity or subunits. Separate meta-analyses of mood disorder studies, MDD and BD, revealed moderate effect sizes for similar abnormality patterns in the expression of complex I with SZ in frontal cortex, cerebellum and striatum, whereas evidence for complex IV alterations was low. By contrast, the neurodegenerative disorders, AD and PD, showed strong effect sizes for shared deficits in complex I and IV, such as in peripheral blood, frontal cortex, cerebellum, and substantia nigra. Beyond the diseased state, there was an age-related robust decline in both complexes I and IV. In summary, the strongest support for a role for complex I and/or IV deficits, is in the pathophysiology of PD and AD, and evidence is less robust for MDD, BD, or SZ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in the pathophysiology of major psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) [1], bipolar disorder (BD) [2] and schizophrenia (SZ) [3], as well as neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease (AD) [4] and Parkinson disease (PD) [4]. Mitochondria are intracellular organelles that produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the main source of cellular energy. Impaired mitochondrial function results in decreased ATP production, impaired bioenergetics, apoptosis and oxidative stress [5]. Prior to the generation of ATP, the electrons extracted from nutrients are transported along the electron transport chain (ETC) and the energy released is directed into a transmembrane proton.

Research has identified two enzymes of the ETC located at the inner mitochondrial membrane as being particular impaired in these five disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, and PD. The first enzyme, complex I (NADH dehydrogenase, NDU) consists of 45 subunits, seven of which are encoded by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and the remaining subunits by nuclear DNA (nDNA). Complex I is one of the entry enzymes of cellular respiration or oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondrion. It is also the largest multimeric enzyme complex of the ETC and is a major contributor to the generation of the proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane, which drives ATP production. The second enzyme of interest, complex IV (cytochrome-c-oxidase, COX) consists of 13 subunits, three of which are encoded by mtDNA, the remainder by nDNA. Complex IV catalyzes the final step in the mitochondrial ETC and, due to its rate-limiting role in this oxidative process [6], has been proposed as a key markers of mitochondrial function [7]. Numerous excellent reviews [1,2,3,4] have discussed the details of impairments in both complex I and IV enzyme activities and subunit assembly within each of the above mentioned disorders. A meta-analysis summarizing the findings across these disorders could not be found in the literature. The remaining complexes II (succinate dehydrogenase), III (cytochrome c reductase) and V (ATP synthase) either have not been studied, or they have been studied to a much smaller degree in these five disorders, compared with complex I and IV, and thus there are too few data for a meta-analysis.

We chose these five disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, and PD not only because of the potential common mitochondrial dysfunction, but also based on their clinical similarities. Though regarded as different disorders in major classification systems like DSM and ICD, there is also overlap in clinical symptoms. Depression is found in mood disorders, but is also frequent in schizophrenia and both AD and PD [8, 9]. Psychotic symptoms are observed in MDD and BD, as well as SZ ((DSM-IV-TR), [10]). Although, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases have distinct brain histopathology, both are age-related neurodegenerative conditions characterized by memory loss and depression and have some commonality in molecular pathogenesis, such as proteinopathy, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress [11]. Cross-disorder commonalities are also found in schizophrenia sharing dopaminergic abnormalities with Parkinson’s [12] and cognitive impairment (dementia praecox) with Alzheimer’s [13].

Beyond disease states, normal aging plays an independent role in mitochondrial ETC function [14]. To separate the influence of age from that of disease, we therefore additionally meta-analyzed complex I and IV functioning in healthy older versus younger individuals. The present meta-analyses aimed to provide a synthesis of the work done on complex I and IV that can guide future research and stimulate development of novel in vivo technologies such as for example the assessment of the redox states of complex I NAD+/NADH ratio [15, 16] or oxidized complex IV [17].

Materials and methods

Literature search and study identification

We conducted a structured literature search in the PubMed, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and Google Scholar, to identify studies published between January 1980 and January 2018 using the search strings ‘NADH dehydrogenase’ OR ‘cytochrome-c-oxidase’ OR ‘complex I’ OR ‘complex IV’ AND ‘major depressive disorder’ OR ‘bipolar disorder’ OR ‘schizophrenia’ OR ‘Alzheimer’ OR ‘Parkinson’ OR ‘age/aging’. We manually reviewed reference lists in all retrieved articles for related publications.

Inclusion criteria were: studies investigated either complex I and/or complex IV, studies published in the English language, studies reporting original human data and studies that investigated patients in comparison with a control group. Exclusion criteria were: animal studies, cellular studies, genetic studies, studies with less than three subjects per group, case reports, letters to the editor and editorials and publications not reporting original data.

Data extraction

Aggregated data were extracted for each of the disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, PD and normal aging (AGING). Aggregated data contained quantitative data (i.e., number of patients and controls, mean age of patients, and controls), qualitative information (i.e., methods such as enzyme activity or subunits at the level of mRNA or protein expression, and tissues assayed, such as peripheral blood, muscle, or brain regions of interest, ROIs) and outcomes (effect sizes in terms of the standardized mean difference, SMD, and p-values). Enzyme activity was extracted as a corrected ratio to citrate synthase to normalize for mitochondrial content, if available. For studies on AGING, we chose a breakpoint of mean 60 years [18] to derive group differences between older (> 60) and younger (< 60) individuals using t-test. In case of medication reported in the studies, both un-medicated and medicated cohorts were included. In case of BD, data were included from both BD I and BD II during depressive episodes, but not manic episodes.

The authors of some studies were contacted for permission to reuse original data [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]; no answer was received in some cases and the data could therefore not or only partially included [19, 20, 23, 25]. Some data were read from figures [18, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Multivariate random-effect meta-analyses

Separate meta-analyses were first computed for each disorder. Moderator variables were generated representing the combination of two aspects: (1) method (enzyme activity or subunit); and (2) tissue (blood, muscle, or ROI). A moderator was included in the meta-analysis only if it was reported by at least three studies. This threshold was chosen after extensive prior testing in order to avoid spurious results.

A summary meta-analysis was computed across all disorders. Here, the moderator variable consisted of the five disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, PD, and AGING. This analysis included all data found to be eligible in the present work and thus also included rare outcomes that could not be included in the separate disease/aging meta-analyses.

For all meta-analyses, a multivariate random-effect model was applied based on the Metafor package [46] as implemented in R [47]. The multivariate model accounts for heterogeneity and dependency in the underlying true effects of multiple moderators that can overlap within subjects and studies (random factors). To adjust for age effects, the age-difference between patients and controls was added as a continuous covariate. To adjust for sample size, the effects were weighted based on study size. To allow for heterogeneity differences between moderators, an unstructured variance-covariance matrix was applied (rma.mv function; observed effects = SMD + age-difference; variance-covariance matrix = COV; weight = study size; variance structure = UN; mods = moderators/disorder; random factors = subject/study; method = REML).

Forest plots were generated to illustrate the results of the multivariate models in terms of the weighted beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran's Q-test and the inconsistency I2 statistic that directly indicates to what extent each outcome contributes to the total variance. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression analysis.

Results

Data extraction

Of 2049 screened studies, 125 studies were eligible for the meta-analyses, some of them for more than one disorder (MDD N = 7, BD N = 19, SZ N = 21, AD N = 43, PD N = 35, AGING N = 18) (Table 1). The overall number of studies reporting on complex I (total N = 101, MDD N = 6, BD N = 19, SZ N = 15, AD N = 19, PD N = 32, AGING N = 11) and complex IV (total N = 104, MDD N = 4, BD N = 10, SZ N = 10, AD N = 39, PD N = 28, AGING N = 15) were similar but varied between disorders. Both complex I and IV were analysed in either peripheral blood elements, such as platelets, lymphocytes, or other blood cells (MDD N = 1, BD N = 10, SZ N = 8, AD N = 9, PD N = 14, AGING N = 2), in muscle biopsies (MDD N = 2, BD N = 0, SZ N = 0, AD N = 0, PD N = 9, AGING N = 14), or in postmortem brain samples (MDD N = 4, BD N = 8, SZ N = 13, AD N = 34, PD N = 14, AGING N = 2). Both complex I and IV were analysed at the level of enzymatic activity (either in blood, muscle, or brain, MDD N = 4, BD N = 5, SZ N = 11, AD N = 32, PD N = 32, AGING N = 14), or of their subunits by mRNA level (only brain, MDD N = 3, BD N = 7, SZ N = 7, AD N = 7, PD N = 1, AGING N = 2) or protein level (only brain, MDD N = 3, BD N = 12, SZ N = 7, AD N = 6, PD N = 3, AGING N = 5). In the following, enzyme activity is denoted with NDU/COX respectively, whereas subunits as assessed by either mRNA or protein expression are referred to with their full names.

Note that we combined data from levels of mRNA/protein expression for all subunits. The correlation between mRNA and protein expression is generally thought to be around 40% [48, 49], which is typically attributed to other levels of regulation between transcript and protein product [50]. We separated the findings in a pre-analysis but found no significant differences between mRNA and protein expression and therefore presented the results together.

Assay of enzyme activity was more common in studies of neurodegenerative disorders, AD (88%) and PD (66%); whereas, the assessment of mRNA/protein expression was more common in studies of mood disorders, MDD (60%), BD (79%) and SZ (56%). None of the five disorders, however, showed differences in enzyme activity or mRNA/protein expression for complex I or IV (p > 0.05). Moreover, there were no differences between peripheral blood and brain in the enzyme activity/mRNA/protein levels of complex I and IV (p > 0.05).

All studies involved subjects over 18 years old, except two studies examined early-onset SZ patients below age 18 years [27, 51]. The mean age-difference between cases and controls differed between disorders (main effect F = 35.21, p < 0.0001). Psychiatric studies, MDD (mean age-difference ± STD = −0.7 ± 3.9), BD (mean age-difference ± STD = 0.8 ± 4.9) and SZ (mean age-difference ± STD = −1.0 ± 3.7) included closer age-matched cases and controls compared with AD (mean age-difference ± STD = 5.0 ± 7.5) or PD (mean age-difference ± STD = 5.3 ± 5.9) as indicated by significant post hoc comparisons (p < 0.0001). Some studies did not provide mean ages for cases and/or controls [52,53,54,55,56], for which we therefore assumed zero age-difference.

Multivariate random-effect meta-analyses

Meta-analyses were performed for each of the disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, PD, and AGING. Based on the precondition that a moderator was reported at least three times across studies, the number of studies finally included in the meta-analyses (and the percentage of the eligible studies) differed between disorders MDD (complex I N = 4 (67%), complex IV N = 2 (50%)), BD (complex I N = 16 (84%), complex IV N = 3 (30%)), SZ (complex I N = 14 (93%), complex IV N = 6 (60%)), AD (complex I N = 12 (63%), complex IV N = 33 (85%)), PD (complex I N = 29 (91%), complex IV N = 24 (86%), and AGING (complex I N = 7 (64%), complex IV N = 14 (93%)).

Mood disorders

In MDD (Fig. 1a), complex I subunits NDUFS1cerebellum (p = 0.0075), NDUFV1cerebellum (p = 0.00014), and NDUFV2cerebellum (p = 0.00051) were lower in cerebellum and subunit NDUFV1frontal (p = 0.0047) was lower in frontal cortex compared with controls. No differences were found for complex IV (note that only in this case, we set the moderator threshold to at least two).

Forest plots MDD, BD, and SZ. Multivariate random-effect estimates of the SMD (95% CI, p-values) of complex I (NDU) and IV (COX) enzyme activity and subunits are shown both in numerical and graphical form. Values lower than 0 indicate that patients had lower levels than controls (CO), and vice versa for values greater than 0; the dashed vertical line at SMD = 0 indicates no effect. The size of the filled circles for each estimated SMD is proportional to the weight of the studies. P putamen, NA nucleus accumbens, GP globus pallidus

In BD (Fig. 1b), complex I subunit NDUFS1cerebellum (p < 0.0001) was lower in cerebellum, subunits NDUFS1frontal (p = 0.033), and NDUFS7frontal (p < 0.0001) were lower in frontal cortex and subunit NDUFS1striatum (p = 0.0023) was lower in striatum compared with controls. No differences were found for complex IV.

In SZ (Fig. 1c), complex I subunit NDUFV2blood (p = 0.019) was lower in blood, whereas subunit NDUFS1blood (p = 0.00086) was higher in blood compared with controls. Further, subunits NDUFS1striatum (p = 0.00072), NDUFV1striatum (p < 0.0001), and NDUFV2striatum (p < 0.0001) were lower in striatum, subunit NDUFV1frontal (p = 0.011) was lower in frontal cortex, whereas subunit NDUFV2parietal (p = 0.019) was higher in parietal cortex compared with controls. Complex IV enzyme activity was lower in frontal cortex (COXfrontal p = 0.016), but higher in basal ganglia (COXNA/GP/P p < 0.0001, nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus and putamen) compared with controls.

We also assessed the overlap in findings between MDD, BD, and SZ using meta-regressions. Results confirmed lower NDUFS1/NDUFV1/NDUFV2 levels in the cerebellum in MDD (p = 0.005/p = 0.001/p = 0.006) and in some subunits also BD (p = 0.088/p = 0.001/p = 0.258) compared to SZ, respectively. By contrast, lower NDUFS1/NDUFV1/NDUFV2 levels in striatum were observed in SZ compared to MDD (p = 0.001/p < 0.0001/p < 0.0001) and in some subunits also BD (p = 0.250/p < 0.0001/p < 0.0001), respectively. Further, both BD (p = 0.024) and SZ (p = 0.008) revealed higher levels of NDUFV2 in the parietal cortex compared to MDD. Last, in BD, subunit NDUFS1blood levels (p = 0.002) in blood and subunit NDUFS7frontal (p = 0.009) in frontal cortex were lower compared to SZ.

Neurodegenerative disorders

In AD (Fig. 2a), complex I enzyme activity in the temporal cortex (NDUtemporal/entorhinal p = 0.0023) and subunits NDUFA1/4/7-9blood (p < 0.0001), NDUFB2/3/6blood (p < 0.0001) and NDUFS3/4/5blood (p < 0.0001) were lower in blood compared with controls. It should be noted that these subunits were reported by Lunnon et al. [57], which was the largest study eligible for the present work with a total of 209 subjects (patients N = 104, controls N = 105). Initially only a small subset of that study could be included in the meta-analysis because of the high moderator threshold; in order to include more of the results from that study, we summarized results across subunits to build sufficient moderators.

Forest plots AD, PD, and AGING. Multivariate random-effect estimates of the SMD (95% CI, p-values) of complex I (NDU) and IV (COX) enzyme activity and subunits are shown both in numerical and graphical form. Values lower than 0 indicate that patients (or older (O) individuals) had lower levels than controls (CO) (or younger (Y) individuals), and vice versa for values greater than 0; the dashed vertical line at SMD = 0 indicates no effect. The size of the filled circles for each estimated SMD is proportional to the weight of the studies

Complex IV enzyme activity was lower in frontal cortex (COXfrontal p = 0.044), motor cortex (COXmotor p = 0.0003), occipital cortex (COXocciptal p = 0.032), parietal cortex (COXparietal p = 0.00069), temporal/entorhinal cortex (COXtemporal/entorhinal p = 0.00012), and hippocampus (COXhippocampus p < 0.0001) compared to controls. Subunit COX2hippocampus in hippocampus (p < 0.0001) and subunit COX7blood in peripheral blood (p = 0.011) were lower.

In PD (Fig. 2b), complex I enzyme activity in peripheral muscle (NDUmuscle p = 0.000084) as well as in substantia nigra (NDUsubstantia nigra p = 0.006) was lower compared to controls. Complex IV enzyme activity in frontal cortex (COXfrontal p = 0.036) was also lower.

The overlap between AD and PD was assessed using meta-regressions. Results showed comparable patterns of enzyme activity in blood (COXblood p = 0.981) and brain such as in frontal cortex (NDUfrontal p = 0.171, COXfrontal p = 0.711), cerebellum (COXcerebellum p = 0.582) and substantia nigra (COXsubstantia nigra p = 0.671), indicating no significant differences between AD and PD.

Aging

To assess complex I and IV functioning in normal aging, we performed a separate meta-analysis in healthy subjects using a breakpoint of 60 years [18] (Fig. 2c). Older (≥60 years) subjects in comparison with younger (<60 years) subjects had lower complex I enzyme activity in frontal cortex (NDUfrontal p < 0.0001) and muscle (NDUmuscle p < 0.0001, NDUFB8muscle p = 0.00015). Similarly, complex IV enzyme activity was lower in frontal cortex (COXfrontal p = 0.00072) and muscle (COXmuscle p = 0.00027, COX2muscle p < 0.0001) in older compared to younger subjects.

Summary comparison of all cases and controls

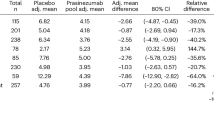

A summary meta-analysis was performed to categorize the disorders according to the severity of overall mitochondrial impairments (Fig. 3). Robust deficits were observed for complex I in PD (p = 0.0016) and AGING (p = 0.009) and for complex IV in AD (p = 0.004) and AGING (p < 0.0001). MDD (p < 0.0001) also showed an effect on complex I; however, it was based on small samples sizes from few studies and can therefore not be considered a robust result. The main effect across both complex I and IV was significant in PD (p = 0.00058), AD (p = 0.049) and AGING (p < 0.0001) indicating that these three conditions were also affected if both complex I and IV are considered.

Forest plot Summary. Multivariate random-effect estimates of the SMD (95% CI, p-values) of complex I and IV are shown both in numerical and graphical form. SMD are ordered according to their strengths. Values lower than 0 indicate that patients (P) had lower levels than controls (CO), and vice versa for values greater than 0; the dashed vertical line at SMD = 0 indicates no effect. The size of the filled circles for each estimated SMD is proportional to the weight of the studies

Heterogeneity and publication bias

Overall, there was a high degree of heterogeneity (Table 2). The I2 for the five disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, and PD ranged between 80 and 100%. Noticeable, there was low heterogeneity in AGING in both complex I (Q = 27.934, p = 0.218, I2 = 18%) and IV (Q = 11.684, p = 1, I2 = 0%). Putative low heterogeneity was observed in MDD for complex IV (Q = 0.030, p = 1, I2 = 0%), most likely explained by the fact that the data came from few studies (N = 4).

Publication bias as assessed using Egger’s regression test (Table 2) provided non-significant results for most of the data indicating no publication bias. Considerable publication bias was only found in PD for complex I (p = 0.043) and in AGING for complex IV (p = 0.014).

Discussion

Our findings provide a picture of the current findings on complex I and IV in mood and neurodegenerative disorders (Fig. 4). We found that mood disorders, MDD, and BD, share commonalities with SZ in having low expression of complex I subunits. Neurodegenerative disorders, AD, and PD, share similarities in complex I and IV enzyme activity abnormalities. Due to heterogeneity in study findings, strong evidence for complex I and/or IV deficits is present for AD and PD; whereas, the overall proof for the involvement of these complexes in MDD, BD, and SZ is less robust and requires further research. Normal aging is a substantial independent factor contributing to both complex I and IV decline and should be considered when interpreting study heterogeneity.

Schematic overview of our findings. Highlighted are the main findings of the meta-analyses for the five disorders MDD, BD, SZ, AD, PD, and normal aging. Region-specific heterogeneity means that complex levels vary from brain region to brain region (i.e., variation from ROI to ROI); tissue-specific heterogeneity indicates that complex levels vary between tissues (i.e., peripheral blood versus brain)

Mood disorders

Mood disorders show shared patterns of complex I subunits NDUFS1, NDUFV1 and NDUFV2 between MDD and BD on the one hand, and between BD and SZ on the other hand (Fig. 1) [24, 26, 43, 45, 58,59,60]. While, MDD and to some degree BD, have lower levels of NDUFS1, NDUFV1, NDUFV2 in cerebellum compared with SZ, the latter had lower NDUFS1, NDUFV1, NDUFV2 levels in striatum compared with MDD and to some degree BD; this indicates a shared mechanism between MDD and BD that is distinct from SZ. By contrast, BD and SZ had elevated levels of NDUFV2 in parietal cortex compared with MDD, which may indicate a shared mechanism between BD and SZ. These brain regions, i.e., the frontal cortex [61, 62], cerebellum [63, 64], and striatum [65], have been previously suggested to contribute to the pathophysiology of mood disorders and schizophrenia spectrum [66]. Distinct from the mood disorders, SZ has higher complex IV levels in basal ganglia [67, 68] perhaps related to previous neuropathological findings in putamen, nucleus accumbens, and globus pallidus [69, 70].

Notably, while most of the eligible studies pointed to dysregulation of complex I and/or IV, the reported direction of change has not always been consistent. While some of the heterogeneity may be due to potential differences in the clinical picture like presence of psychosis in MDD or BD and presence of depression in SZ, several other explanations may underlie these discrepancies. First, there may be state-related differences in the expression of complex I and IV. For example BD patients showed up-regulation of complex I subunits during manic compared to depressive episodes [71] maybe related to elevated brain metabolism in frontal and temporal cortex [72]. Similarly in SZ, state-dependence has been suggested with increased complex I activity in active psychotic patients but decreased activity in patients with residual schizophrenia [73,74,75]. Unfortunately, postmortem studies were unable to provide information on whether patients were depressed, manic or euthymic at time of death. Second, there may be brain region-specific heterogeneity, possibly indicating that ETC energy production varies from region to region, as previously exemplarily shown [59]. Third, there may be tissue-specific differences between blood samples from living patients and brain samples obtained postmortem. For example, it has been hypothesized that ETC genes are upregulated in blood, but downregulated in some or all brain regions in BD [76] and SZ [77], although this was not confirmed statistically by the present meta-analysis. Fourth, the majority of patients were receiving psychotropic medication, such as antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics. All of these pharmacological agents have been reported to potentially interfere or even inhibit the mitochondrial ETC [78]. Finally, differences in brain pH at the time of death may explain difference in gene expression [79]. Larger sample studies of medication-free patients are needed to clarify more precisely the relationships between diagnosis, mood state, treatment status, and brain pH in mood disorders and schizophrenia pathophysiology. There is also evidence of shared global gene expression patterns between mood disorders and schizophrenia that go beyond purely mitochondrial function that could be investigated in relation [80].

Neurodegenerative disorders

Neurodegenerative disorders AD and PD show similarities in the impairment of complex I and IV enzyme activities in the blood, frontal cortex, cerebellum, and substantia nigra (Fig. 2). These brain regions are potentially involved in the cognitive decline and neuronal loss-in-AD [81, 82], as well as in the motor and non-motor related degeneration of neurotransmitter systems in PD [83, 84].

In AD, there are a well-documented deficit in both complex I and IV [4, 85, 86]. These deficits are thought to be due to the neuronal toxicity induced by amyloid β peptide (Aβ), an important component of AD pathogenesis, in that Aβ accumulates in mitochondria, directly inhibits mitochondrial enzymes, perpetuates oxidative stress, and leads to a hypometabolic state, which causes mitochondrial dysfunction [87,88,89,90]. The meta-analysis supported these findings in terms of downregulated complex I and IV in the blood [57, 91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98], frontal cortex [38, 44, 56, 99,100,101,102,103,104], motor cortex [102, 105, 106], occipital cortex [44, 107, 108], parietal cortex [36, 44, 52, 102, 107, 108], temporal/entorhinal cortex [37, 44, 52, 54, 99, 102, 107,108,109,110] and hippocampus [33, 34, 36, 44, 52, 99, 102, 106, 111,112,113,114]. The strength of the effect sizes are in line with findings of neuronal loss in entorhinal cortex, hippocampus and association neocortex [81]. Due to limited data, the meta-analysis was not able to distinguish between Brack stages in AD. A large study in AD (N = 148) reported less expression of complex I and IV subunits in entorhinal and frontal cortex in disease stages V–VI but not in stages I–II [115]. A smaller study (N = 18) compared complex I and IV enzyme activity in frontal cortex in stages III–VI to stages I–II but found no stage-dependence [19]. There were also no differences between early-versus late-onset AD (age <60 versus age >60) [96].

In PD, the meta-analysis points to downregulation of both complex I and IV enzyme activity in the blood, muscle, and brain. For example, inhibition of complex I has been reported in platelets [110, 116,117,118,119,120,121,122] and skeletal muscles [123,124,125,126,127], although there was dissenting studies in platelets [128, 129] or muscle [55, 130, 131]. Similarly, complex IV has been found to be decreased in blood [116, 118, 121, 122, 132, 133] and muscle [124, 125, 127, 131], while others could not confirm this for either platelets [120, 134] or muscle [53, 55, 123, 126, 130]. Within the brain, some studies reported lower complex I enzyme activity in substantia nigra [110, 130, 135,136,137], as well as low activity and impaired assembly of complex I in frontal cortex [29, 31, 40, 135, 138, 139], the latter not being confirmed in the meta-analysis. Similarly, complex IV in the brain is reported to be low in frontal cortex [31, 36, 135, 138, 139] and substantia nigra [36, 110, 130, 136, 140], the latter finding not confirmed here. Note that although all data eligible for the meta-analysis were obtained from patients suffering from the more common sporadic form of PD, derangements in mitochondrial metabolism and oxidative stress have also been strongly linked to the less common familial form of PD [141].

Likewise for mood disorders, medication may affect mitochondrial functioning in neurodegeneration. Cholinesterase (ChE) inhibitors and amyloid-beta binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) modulators are used to treat the key symptoms in AD in order to improve activities of daily living, behavior, and cognition [142]. Most of these drugs can negatively affect both complex I and IV [143]. There are however newly developed ChEs and ABADs, as well as other more recent drug developments that target multiple AD pathophysiological pathways that are thought to have a better outcome on mitochondrial function [144]. By contrast, in PD, levodopa, cardidopa, and selegiline, which are used to treat PD motor symptoms, have not been shown not affect complex I and IV in PD [145, 146]. Similarly, melatonin that is used as sleep/wake regulator in PD, acts as an effective antioxidant and mitochondrial function protector [147]. These observations support the hypothesis that impaired complex I and IV activity in PD patients is a characteristic of the disease and not due to medications.

Aging

Normal aging has been associated with a decline in mitochondrial quality [14] and activity of both complex I and IV [6, 148]. The meta-analysis supported these findings in terms of decreased levels of enzyme activity in the muscle [32, 39, 41, 42, 149,150,151,152,153,154,155] and frontal cortex [18, 30, 153, 156] (Fig. 2c). Across all meta-analyses, the effect of aging was the most robust both in terms of the strength of the summary effect sizes (Fig. 3), as well as the low degree of heterogeneity (Table 2).

The decline in both complex I and IV in normal aging [6, 148] as indicated by this meta-analysis can represent a functionally serious impairment of mitochondrial function with respect to basal ATP production [157]. Therefore, aged neurons with lower mitochondrial mass and enzyme activities as well as more dysfunctional mitochondria may be unable to respond adequately to any increased ATP demand [158].

The term normal aging should be considered carefully. Normal aging is thought to be a function of both chronological age as well as biological age [32]. Although the underlying mechanism is still controversial, age-dependent mitochondrial decline may contribute to loss-of-physical capacity and mental exertion [159, 160]. The ‘free radical’ theories of aging [161, 162] state that reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced aberrantly during mitochondrial electron transport damage mitochondrial components, including mtDNA. Since, mtDNA encodes essential complex I and IV proteins [163], its damage and mutagenesis would disrupt ETC complex assembly and, in turn, lead to more ROS production, cellular oxidative stress and tissue dysfunction that promote aging [164]. This theory, however, has been thought to be too simplistic and there is debate about other age-dependent cellular changes that may be important in precipitating the decline in mitochondrial ETC [160].

Summary comparison of all cases and controls

Summarizing the overall severity of mitochondrial impairment in the five disorders (Fig. 3) indicates that major psychiatric disorders MDD, BD, and SZ show less robust effects. The small effect sizes in those pathologies were most likely due to the small number of studies with small sample sizes, large region-specific heterogeneity and variation in medication and treatment, which made in harder to detect underlying mitochondrial disease. By contrast, strong evidence for a complex I deficit is found in PD, whereas a complex IV deficit is present in AD; with the simultaneous decline in complex I and IV being significant in both AD and PD. These results indicate an interaction of complex I with IV involved in the assembly and stability of complex I [165,166,167].

The interpretation of the strengths of the effect sizes between the five disorder compared with normal aging, as shown in Fig. 3, should however be cautious. Aging is a major risk factor for developing both AD [168] and idiopathic PD [169]. Consequently, the effects of normal aging and that of the diseases cannot be clearly separated because of their inter-dependence. Of note, patients in all studies included were age-matched, thus in principle presenting age-adjusted effects. We therefore argue that the lesser effects in mood disorders is not related to the younger age of these patients, and the larger effects in AD is also not related to older age.

Further research is required to enlarge sample sizes and strengthen the evidence base. Our results may stimulate the application of novel in vivo technologies such as assessing complex I NAD+/NADH redox state via auto-fluorescence [16] or magnetic resonance spectroscopy [15] and complex IV redox states via functional near-infrared spectroscopy [17].

References

Bansal Y, Kuhad A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14:610–8.

Kato T. Neurobiological basis of bipolar disorder: mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis and beyond. Schizophr Res. 2017;187:62–66.

Bergman O, Ben-Shachar D. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) deficits in schizophrenia: possible interactions with cellular processes. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:457–69.

Onyango I, Khan S, Bennett J. Mitochondria in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Front Biosci. 2017;22:854–72.

Hroudová J, Fišar Z. Connectivity between mitochondrial functions and psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:130–41.

Arnold S. Cytochrome c oxidase and its role in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;305–339.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3573-0_13.

Srinivasan S, Avadhani NG. Cytochrome c oxidase dysfunction in oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1252–63.

Zhuo C, Xue R, Luo L, Ji F, Tian H, Qu H, et al. Efficacy of antidepressive medication for depression in Parkinson disease: a network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96:e6698.

Lanctôt KL, Amatniek J, Ancoli-Israel S, Arnold SE, Ballard C, Cohen-Mansfield J, et al. Neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: new treatment paradigms. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;3:440–9.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

Aarsland D, Cummings J, Larsen J. Neuropsychiatric differences between Parkinson’s disease with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2001;16:184–91.

Brisch R, Saniotis A, Wolf R, Bielau H, Bernstein H-G, Steiner J, et al. The role of dopamine in schizophrenia from a neurobiological and evolutionary perspective: old fashioned, but still in vogue. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:47.

Lyketsos CG, Peters ME. Dementia in patients with schizophrenia: evidence for heterogeneity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1075–6.

Sun N, Youle RJ, Finkel T. The mitochondrial basis of aging. Mol Cell. 2016;61:654–66.

Zhu X-H, Lu M, Lee B-Y, Ugurbil K, Chen W. In vivo NAD assay reveals the intracellular NAD contents and redox state in healthy human brain and their age dependences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2876–81.

Blacker TS, Duchen MR. Investigating mitochondrial redox state using NADH and NADPH autofluorescence. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:53–65.

Bale G, Elwell C, Tachtsidis I. From Jöbsis to the present day: a review of clinical near-infrared spectroscopy measurements of cerebral cytochrome-c-oxidase. J Biomed Opt. 2016;21:91307.

Cabré R, Naudí A, Dominguez-Gonzalez M, Ayala V, Jové M, Mota-Martorell N, et al. Sixty years old is the breakpoint of human frontal cortex aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;103:14–22.

Manczak M, Park BS, Jung Y, Reddy PH. Differential expression of oxidative phosphorylation genes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;5:147–62.

Thomas R, Keeney P, Bennett J. Impaired complex-I mitochondrial biogenesis in Parkinson disease frontal cortex. J Park Dis. 2012;2:67–76.

Washizuka S, Iwamoto K, Kakiuchi C, Bundo M, Kato T. Expression of mitochondrial complex I subunit gene NDUFV2 in the lymphoblastoid cells derived from patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neurosci Res. 2009;63:199–204.

Washizuka S, Kakiuchi C, Mori K, Tajima O, Akiyama T, Kato T. Expression of mitochondria-related genes in lymphoblastoid cells from patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:146–52.

Altar CA, Jurata LW, Charles V, Lemire A, Liu P, Bukhman Y, et al. Deficient hippocampal neuron expression of proteasome, ubiquitin, and mitochondrial genes in multiple schizophrenia cohorts. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:85–96.

Karry R, Klein E, Ben Shachar D. Mitochondrial complex I subunits expression is altered in schizophrenia: a postmortem study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:676–84.

Konradi C, Eaton M, MacDonald ML, Walsh J, Benes FM, Heckers S. Molecular evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:300–8.

Andreazza AC, Wang J-F, Salmasi F, Shao L, Young LT. Specific subcellular changes in oxidative stress in prefrontal cortex from patients with bipolar disorder. J Neurochem. 2013;127:552–61.

Mehler-Wex C, Duvigneau JC, Hartl RT, Ben-Shachar D, Warnke A, Gerlach M. Increased mRNA levels of the mitochondrial complex I 75-kDa subunit. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:504–7.

Munkholm K, Peijs L, Vinberg M, Kessing LV. A composite peripheral blood gene expression measure as a potential diagnostic biomarker in bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e614.

Mythri RB, Venkateshappa C, Harish G, Mahadevan A, Muthane UB, Yasha TC, et al. Evaluation of markers of oxidative stress, antioxidant function and astrocytic proliferation in the striatum and frontal cortex of Parkinson’s disease brains. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:1452–63.

Ojaimi J, Masters CL, Opeskin K, McKelvie P, Byrne E. Mitochondrial respiratory chain activity in the human brain as a function of age. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;111:39–47.

Parker WD, Parks JK, Swerdlow RH. Complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease frontal cortex. Brain Res. 2008;1189:215–8.

Safdar A, Hamadeh MJ, Kaczor JJ, Raha S, deBeer J, Tarnopolsky MA. Aberrant mitochondrial homeostasis in the skeletal muscle of sedentary older adults. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10778.

Simonian N, Hyman B. Functional alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: diminution of cytochrome oxidase in the hippocampal formation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52:580–5.

Simonian N, Hyman B. Functional alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: selective loss of mitochondrial-encoded cytochrome oxidase mRNA in the hippocampal formation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;53:508–12.

Trounce I, Byrne E, Marzuki S. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory chain function: possible factor in ageing. Lancet. 1989;333:637–9.

Chagnon P, Bétard C, Robitaille Y, Cholette A, Gauvrea D. Distribution of brain cytochrome oxidase activity in various neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroreport: Int J Rapid Commun Res Neurosci. 1995;6:711–5.

Chandrasekaran K, Hatanpää K, Brady DR, Stoll J, Rapoport SI. Downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease: loss of cytochrome oxidase subunit mRNA in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Brain Res. 1998;796:13–19.

Devi L, Prabhu BM, Galati DF, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer’s disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9057.

Distefano G, Standley RA, Dubé JJ, Carnero EA, Ritov VB, Stefanovic-Racic M, et al. Chronological age does not influence ex-vivo mitochondrial respiration and quality control in skeletal muscle. J Gerontol: Ser A. 2017;72:535–42.

Gatt AP, Duncan OF, Attems J, Francis PT, Ballard CG, Bateman JM. Dementia in Parkinson’s disease is associated with enhanced mitochondrial complex I deficiency. Mov Disord. 2016;31:352–9.

Gueugneau M, Coudy-Gandilhon C, Théron L, Meunier B, Barboiron C, Combaret L, et al. Skeletal muscle lipid content and oxidative activity in relation to muscle fiber type in Aging and Metabolic syndrome. J Gerontol: Ser A. 2015;70:566–76.

Hsieh R, Hou J, Hsu H, Wei Y. Age-dependent respiratory function decline and DNA deletions in human muscle mitochondria. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;32:10009–22.

Kim HK, Andreazza AC, Elmi N, Chen W, Young LT. Nod-like receptor pyrin containing 3 (NLRP3) in the post-mortem frontal cortex from patients with bipolar disorder: a potential mediator between mitochondria and immune-activation. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;72:43–50.

Kish SJ, Bergeron C, Rajput A, Dozic S, Mastrogiacomo F, Chang L-J, et al. Brain cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1992;59:776–9.

Andreazza AC, Shao L, Wang J, Young L. Mitochondrial complex i activity and oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins in the prefrontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:360–8.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48.

R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. VIenna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008.

Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:227–32.

Abreu RdeS, Penalva LO, Marcotte EM, Vogel C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:1512–26.

Maier T, Güell M, Serrano L. Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3966–73.

Taurines R, Thome J, Duvigneau JC, Forbes-Robertson S, Yang L, Klampfl K, et al. Expression analyses of the mitochondrial complex I 75-kDa subunit in early onset schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder: increased levels as a potential biomarker for early onset schizophrenia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:441–8.

Reichmann H, Fhirke S, Hebenstreit G, Schrubar H, Riederer P. Analyses of energy metabolism and mitochondrial genome in post-mortem brain from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol. 1993;240:377–80.

Wiedemann FR, Winkler K, Lins H, Wallesch C-W, Kunz WS. Detection of respiratory chain defects in cultivated skin fibroblasts and skeletal muscle of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;893:426–9.

Cooper JM, Wischik C, Schapira AHV. Mitochondrial function in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1993;341:969–70.

DiDonato S, Zeviani M, Giovannini P, Savarese N, Rimoldi M, Mariotti C, et al. Respiratory chain and mitochondrial DNA in muscle and brain in Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurology. 1993;43:2262.

Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Russell RL, Atwood CS, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3017–23.

Lunnon K, Ibrahim Z, Proitsi P, Lourdusamy A, Newhouse S, Sattlecker M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and immune activation are detectable in early alzheimer’s disease blood. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:685–710.

Sun X, Wang J-F, Tseng M, Young LT. Downregulation in components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in the postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:189–96.

Ben-Shachar D, Karry R. Neuroanatomical pattern of mitochondrial complex I pathology varies between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3676.

Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Kato T. Altered expression of mitochondria-related genes in postmortem brains of patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, as revealed by large-scale DNA microarray analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:241–53.

Brakowski J, Spinelli S, Dörig N, Bosch OG, Manoliu A, Holtforth MG, et al. Resting state brain network function in major depression – depression symptomatology, antidepressant treatment effects, future research. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;92:147–59.

Hibar DP, Westlye LT, Doan NT, Jahanshad N, Cheung JW, Ching CRK, et al. Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder: an MRI analysis of 6503 individuals from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. (2017)https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.73

Shinn AK, Roh YS, Ravichandran CT, Baker JT, Öngür D, Cohen BM. Aberrant cerebellar connectivity in bipolar disorder with psychosis. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017;2:438–48.

Jiang J, Zhao Y-J, Hu X-Y, Du M-Y, Chen Z-Q, Wu M, et al. Microstructural brain abnormalities in medication-free patients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging. J Psychiatry Neuroscience. 2017;42:150–63.

Pacifico R, Davis RL. Transcriptome sequencing implicates dorsal striatum-specific gene network, immune response and energy metabolism pathways in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;22:441.

Dietsche B, Kircher T, Falkenberg I. Structural brain changes in schizophrenia at different stages of the illness: a selective review of longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51:500–8.

Prince JA, Blennow K, Gottfries CG, Karlsson I, Oreland L. Mitochondrial function is differentially altered in the basal ganglia of chronic schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:372.

Prince JA, Harro J, Blennow K, Gottfries CG, Oreland L. Putamen mitochondrial energy metabolism is highly correlated to emotional and intellectual impairment in schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:284.

Mamah D, Wang L, Erausquin DBGAde, Gado M, Csernansky JG. Structural analysis of the basal ganglia in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:59–71.

Womer FY, Wang L, Alpert K, Smith MJ, Csernansky JG, Barch D, et al. Basal ganglia and thalamic morphology in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014;223:75–83.

Akarsu S, Torun D, Erdem M, Kozan S, Akar H, Uzun O. Mitochondrial complex I and III mRNA levels in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;184:160–3.

Shao L, Martin MV, Watson SJ, Schatzberg A, Akil H, Myers RM, et al. Mitochondrial involvement in psychiatric disorders. Ann Med. 2008;40:281–95.

Rosenfeld M, Brenner-Lavie H, Ari SG-B, Kavushansky A, Ben-Shachar D. Perturbation in mitochondrial network dynamics and in complex I dependent cellular respiration in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:980–8.

Ben-Shachar D, Bonne O, Chisin R, Klein E, Lester H, Aharon-Peretz J, et al. Cerebral glucose utilization and platelet mitochondrial complex I activity in schizophrenia: a FDG-PET study. Progress NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:807–13.

Dror N, Klein E, Karry R, Sheinkman A, Kirsh Z, Mazor M, et al. State-dependent alterations in mitochondrial complex I activity in platelets: a potential peripheral marker for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:995.

Beech RD, Lowthert L, Leffert JJ, Mason PN, Taylor MM, Umlauf S, et al. Increased peripheral blood expression of electron transport chain genes in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:813–24.

Ben-Shachar D, Karry R. Sp1 expression is disrupted in schizophrenia; a possible mechanism for the abnormal expression of mitochondrial complex I genes, NDUFV1 and NDUFV2. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e817.

Manji H, Kato T, Di Prospero NA, Ness S, Beal MF, Krams M, et al. Impaired mitochondrial function in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:293.

Vawter M, Tomita H, Meng F, Bolstad B, Li J, Evans S, et al. Mitochondrial-related gene expression changes are sensitive to agonal-pH state: implications for brain disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:615–79.

Gandal MJ, Haney JR, Parikshak NN, Leppa V, Ramaswami G, Hartl C, et al. Shared molecular neuropathology across major psychiatric disorders parallels polygenic overlap. Science. 2018;359:693.

Perluigi M, Barone E, Di Domenico F, Butterfield DA. Aberrant protein phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease brain disturbs pro-survival and cell death pathways. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Basis Dis. 2016;1862:1871–82.

Boublay N, Schott AM, Krolak-Salmon P. Neuroimaging correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 20 years of research. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1500–9.

Atkinson-Clement C, Pinto S, Eusebio A, Coulon O. Diffusion tensor imaging in Parkinson’s disease: review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage: Clin. 2017;16:98–110.

Gao L, Wu T. The study of brain functional connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2016;5:18.

Coskun P, Wyrembak J, Schriner S, Chen H-W, Marciniack C, LaFerla F, et al. A mitochondrial etiology of Alzheimer and Parkinson disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:553–64.

Giachin G, Bouverot R, Acajjaoui S, Pantalone S, Soler-López M. Dynamics of human mitochondrial complex I assembly: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 2016;3:43.

Picone P, Nuzzo D, Caruana L, Scafidi V, Di Carlo M. Mitochondrial dysfunction: different routes to Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;Article ID780179.

Pinho CM, Teixeira PF, Glaser E. Mitochondrial import and degradation of amyloid-β peptide. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Bioenerg. 2014;1837:1069–74.

Readnower R, Sauerbeck A, Sullivan P. Mitochondria, Amyloid β, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011; Article ID 104545.

Cenini G, Rüb C, Bruderek M, Voos W, Gilmore R. Amyloid β-peptides interfere with mitochondrial preprotein import competence by a coaggregation process. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:3257–72.

Mancuso M, Filosto M, Bosetti F, Ceravolo R, Rocchi A, Tognoni G, et al. Decreased platelet cytochrome c oxidase activity is accompanied by increased blood lactate concentration during exercise in patients with Alzheimer disease. Exp Neurol. 2003;182:421–6.

Parker W, Filley C, Parks J. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1302–3.

Parker W, Mahr N, Filley C, Parks J, Hughes D, Young D, et al. Reduced platelet cytochrome c oxidase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1994a;44:1086–90.

Sheehan JP, Swerdlow RH, Miller SW, Davis RE, Parks JK, Parker WD, et al. Calcium homeostasis and reactive oxygen species production in cells transformed by mitochondria from individuals with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4612.

Valla J, Schneider L, Niedzielko T, Coon KD, Caselli R, Sabbagh MN, et al. Impaired platelet mitochondrial activity in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Mitochondrion. 2006;6:323–30.

Cardoso SM, Proença MT, Santos S, Santana I, Oliveira CR. Cytochrome c oxidase is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease platelets. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:105–10.

Feldhaus P, Fraga DB, Ghedim FV, De Luca RD, Bruna TD, Heluany M, et al. Evaluation of respiratory chain activity in lymphocytes of patients with Alzheimer disease. Metab Brain Dis. 2011;26:229.

Fišar Z, Hroudová J, Hansíková H, Spáčilová J, Lelková P, Wenchich L, et al. Mitochondrial respiration in the platelets of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:930–41.

Maurer I, Zierz S, Möller H. A selective defect of cytochrome c oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:455–62.

Parker W, Parks J, Filley C, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B. Electron transport chain defects in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurology. 1994b;44:1090–96.

Pérez-Gracia E, Torrejón-Escribano B, Ferrer I. Dystrophic neurites of senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease are deficient in cytochrome c oxidase. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:261–8.

Wong-Riley M, Antuono P, Ho K-C, Egan R, Hevner R, Liebl W, et al. Cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease: biochemical, histochemical, and immunohistochemical analyses of the visual and other systems. Vision Res. 1997;37:3593–608.

Cavelier L, Jazin EE, Eriksson I, Prince J, Båve U, Oreland L, et al. Decreased cytochrome-c oxidase activity and lack of age-related accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in the brains of schizophrenics. Genomics. 1995;29:217–24.

Long J, He P, Shen Y, Li R. New evidence of mitochondria dysfunction in the female Alzheimer’s brain: deficiency of estrogen receptor-β. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012;30:545–58.

Valla J, Berndt JD, Gonzalez-Lima F. Energy hypometabolism in posterior cingulate cortex of Alzheimer’s patients: superficial laminar cytochrome oxidase associated with disease duration. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4923.

Bosetti F, Brizzi F, Barogi S, Mancuso M, Siciliano G, Tendi EA, et al. Cytochrome c oxidase and mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase (ATP synthase) activities in platelets and brain from patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:371–6.

Mutisya EM, Bowling AC, Beal MF. Cortical cytochrome oxidase activity is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1994;63:2179–84.

Kish SJ, Mastrogiacomo F, Guttman M, Furukawa Y, Taanman J-W, Dozic S, et al. Decreased brain protein levels of cytochrome oxidase subunits in Alzheimer’s disease and in hereditary spinocerebella ataxia disorders. J Neurochem. 1999;72:700–7.

Alikhani N, Guo L, Yan S, Du H, Pinho CM, Chen JX, et al. Decreased proteolytic activity of the mitochondrial amyloid-β degrading enzyme, PreP peptidasome, in Alzheimer’s disease brain mitochondria. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:75–87.

Gu M, Owen A, Toffa SE, Cooper J, Dexter D, Jenner P, et al. Mitochondrial function, GSH and iron in neurodegeneration and Lewy body diseases. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:24–29.

Verwer RWH, Jansen KA, Sluiter AA, Pool CW, Kamphorst W, Swaab DF. Decreased hippocampal metabolic activity in Alzheimer patients is not reflected in the immunoreactivity of cytochrome oxidase subunits. Exp Neurol. 2000;163:440–51.

Aksenov MY, Tucker HM, Nair P, Aksenova MV, Butterfield DA, Estus S, et al. The expression of several mitochondrial and nuclear genes encoding the subunits of electron transport chain enzyme complexes, cytochrome c oxidase, and NADH dehydrogenase, in different brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:767–74.

Chandrasekaran K, Giordano T, Brady DR, Stoll J, Martin LJ, Rapoport SI. Impairment in mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase gene expression in Alzheimer disease. Mol Brain Res. 1994;24:336–40.

Cottrell DA, Blakely EL, Johnson MA, Ince PG, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial enzyme-deficient hippocampal neurons and choroidal cells in AD. Neurology. 2001;57:260.

Armand-Ugon M, Ansoleaga B, Berjaoui S, Ferrer I. Reduced mitochondrial activity is early and steady in the entorhinal cortex but it is mainly unmodified in the frontal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14:1327–34.

Parker W, Boyson S, Parks J. Abnormalities of the electron transport chain in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:719–23.

Varghese M, Pandey M, Samanta A, Gangopadhyay PK, Mohanakumar KP. Reduced NADH coenzyme Q dehydrogenase activity in platelets of Parkinson’s disease, but not Parkinson plus patients, from an Indian population. J Neurol Sci. 2009;279:39–42.

Benecke R, Struemper P, Weiss H. Electron transfer complexes I and IV of platelets are abnormal in Parkinson’s disease but normal in Parkinson-plus syndromes. Brain. 1993;116:1451–63.

Yoshino H, Nakagawa-Hattori Y, Kondo T, Mizuno Y. Mitochondrial complex I and II activities of lymphocytes and platelets in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1992;4:27–34.

Blake CI, Spitz E, Leehey M, Hoffer BJ, Boyson SJ. Platelet mitochondrial respiratory chain function in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1997;12:3–8.

Bravi D, Anderson JJ, Dagani F, Davis TL, Ferrari R, Gillespie M, et al. Effect of aging and dopaminomimetic therapy on mitochondrial respiratory function in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1992;7:228–31.

Krige D, Carroll M, Cooper J, Marsden C, Schapira A. Platelet mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:782–8.

Nakagawa-Hattori Y, Yoshino H, Kondo T, Mizuno Y, Horai S. Is Parkinson’s disease a mitochondrial disorder? J Neurol Sci. 1992;107:29–33.

Shoffner JM, Watts RL, Juncos JL, Torroni A, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defects in parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:332–9.

Bindoff LA, Birch-Machin MA, Cartlidge NEF, Parker WD, Turnbull DM. Respiratory chain abnormalities in skeletal muscle from patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1991;104:203–8.

Blin O, Desnuelle C, Rascol O, Borg M, Paul HPS, Azulay JP, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory failure in skeletal muscle from patients with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1994;125:95–101.

Cardellach F, Martí MJ, Fernández-Solá J, Marín C, Hoek JB, Tolosa E, et al. Mitochondria1 respiratory chain activity in skeletal muscle from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1993;43:2258.

Martín MA, Molina JA, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Benito-León J, Ortí-Pareja M, Campos Y, et al. Respiratory‐chain enzyme activities in isolated mitochondria of lymphocytes from untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurology. 1996;46:1343.

Bronstein JM, Paul K, Yang L, Haas RH, Shults CW, Le T, et al. Platelet mitochondrial activity and pesticide exposure in early Parkinson’s disease. Mov disorders. 2015;30:862–6.

Mann VM, Cooper JM, Krige D, Daniel SE, Schapira AHV, Marsden CD. Brain, skeletal muscle and platelet homogenate mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1992;115:333–42.

Anderson JJ, Bravi D, Ferrari R, Davis TL, Baronti F, Chase TN, et al. No evidence for altered muscle mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:477–80.

Shinde S, Pasupathy K. Respiratory-chain enzyme activities in isolated mitochondria of lymphocytes from patients with Parkinson’s disease: preliminary study. Neurol India. 2006;54:390–3.

Haas RH, Nasirian F, Nakano K, Ward D, Pay M, Hill R, et al. Low platelet mitochondrial complex I and complex II/III activity in early untreated parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:714–22.

Hanagasi HA, Ayribas D, Baysal K, Emre M. Mitochondrial complex I, II/III, and IV activities in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115:479–93.

Mizuno Y, Suzuki K, Ohta S. Postmortem changes in mitochondrial respiratory enzymes in brain and a preliminary observation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1990;96:49–57.

Schägger H. Quantification of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes after blue native electrophoresis and two-dimensional resolution: normal complex I protein amounts in Parkinson’s disease conflict with reduced catalytic activities. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:763–70.

Schapira AHV, Mann VM, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Daniel SE, Jenner P, et al. Anatomic and disease specificity of NADH CoQ1 reductase (Complex I) deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 1990b;55:2142–5.

Barroso N, Campos Y, Huertas R, Esteban J, Molina JA, Alonso A, et al. Respiratory chain enzyme activities in lymphocytes from untreated patients with Parkinson disease. Clin Chem. 1993;39:667.

Keeney PM, Xie J, Capaldi RA, Bennett JP. Parkinson’s disease brain mitochondrial complex I has oxidatively damaged subunits and is functionally impaired and misassembled. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5256.

Schapira AHV, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Jenner P, Clark JB, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1990a;333:1269.

Ryan BJ, Hoek S, Fon EA, Wade-Martins R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in Parkinson’s: from familial to sporadic disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:200–10.

Grossberg GT. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: getting on and staying on. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64:216–35.

Hroudová J, Fišar Z, Korábečny J, Nepovímová E, Spilovská K, Vašková L, et al. In vitro effects of newly developed cholinesterase inhibitors and ABAD modulators on mitochondrial respiration. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:S1022.

Korábečný J, Nepovimová E, Cikánková T, Špilovská K, Vašková L, Mezeiová E, et al. Newly developed drugs for Alzheimer’s disease in relation to energy metabolism, cholinergic and monoaminergic neurotransmission. Neuroscience. 2018;370:191–206.

Shults CW, Nasirian F, Ward DM, Nakano K, Pay M, Hill LR, et al. Cardidopa/Levodopa and selegiline do not affect platelet mitochondrial function in early Parkinsonism. Neurology. 1995;45:344–8.

Dixit A, Srivastava G, Verma D, Mishra M, Singh PK, Prakash O, et al. Minocycline, levodopa and MnTMPyP induced changes in the mitochondrial proteome profile of MPTP and maneb and paraquat mice models of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Basis Dis. 2013;1832:1227–40.

Srinivasan V, Cardinali DP, Srinivasan US, Kaur C, Brown GM, Spence DW, et al. Therapeutic potential of melatonin and its analogs in Parkinson’s disease: focus on sleep and neuroprotection. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:297–317.

Navarro A, Boveris A. The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C670.

Ogborn DI, McKay BR, Crane JD, Safdar A, Akhtar M, Parise G, et al. Effects of age and unaccustomed resistance exercise on mitochondrial transcript and protein abundance in skeletal muscle of men. Am J Physiol-Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R734–R741.

Pestronk A, Keeling R, Choksi R. Sarcopenia, age, atrophy, and myopathy: mitochondrial oxidative enzyme activities. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56:122–8.

Rooyackers OE, Adey DB, Ades PA, Nair KS. Effect of age on in vivo rates of mitochondrial protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15364–9.

Zucchini C, Pugnaloni A, Pallotti F, Solmi R, Crimi M, Castaldini C, et al. Human skeletal muscle mitochondria in aging: lack of detectable morphological and enzymic defects. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1995;37:607–16.

Boffoli D, Scacco SC, Vergari R, Persio MT, Solarino G, Laforgia R, et al. Ageing is associated in females with a decline in the content and activity of the b-c1 complex in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Basis Dis. 1996;1315:66–72.

Emelyanova L, Preston C, Gupta A, Viqar M, Negmadjanov U, Edwards S, et al. Effect of aging on mitochondrial energetics in the human atria. J Gerontol: Series A. 2017;glx160–glx160. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx160.

Lanza IR, Short DK, Short KR, Raghavakaimal S, Basu R, Joyner MJ, et al. Endurance exercise as a countermeasure for aging. Diabetes. 2008;57:2933–42.

Boffoli D, Scacco SC, Vergari R, Solarino G, Santacroce G, Papa S. Decline with age of the respiratory chain activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Basis Dis. 1994;1226:73–82.

Boveris A, Costa L, Cadenas E. The mitochondrial production of oxygen radicals and cellular aging. Oxid Stress Dis. 1999;2:1–16.

Navarro A, Boveris A. Rat brain and liver mitochondria develop oxidative stress and lose enzymatic activities on aging. Am J Physiol-Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1244–R1249.

Payne B, Chinnery P. Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging: Much progress but many unresolved questions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1847:1347–53.

Christian BE, Shadel GS. Aging: it’s SIRTainly possible to restore mitochondrial dysfunction. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R206–R208.

Miquel J, Economos AC, Fleming J, Johnson JE. Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp Gerontol. 1980;15:575–91.

Harman D. Free radical theory of aging. Mutat Res. 1992;275:257–66.

Bonawitz ND, Clayton DA, Shadel GS. Initiation and beyond: multiple functions of the human mitochondrial transcription machinery. Mol Cell. 2006;24:813–25.

Mandavilli BS, Santos JH, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA repair and aging. Mutat Res. 2002;509:127–51.

Schäfer E, Dencher NA, Vonck J, Parcej DN. Three-dimensional structure of the respiratory chain supercomplex I1III2IV1 from bovine heart mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12579–85.

Diaz F, Fukui H, Garcia S, Moraes CT. Cytochrome c oxidase is required for the assembly/stability of respiratory complex I in mouse fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4872–81.

Li Y, D’Aurelio M, Deng J-H, Park J-S, Manfredi G, Hu P, et al. An assembled complex IV maintains the stability and activity of complex I in mammalian mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17557–62.

Swerdlow RH. Brain aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and mitochondria. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Basis Dis. 2011;1812:1630–9.

Reeve A, Simcox E, Turnbull D. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: why is advancing age the biggest risk factor?. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;14:19–30.

Ben-Shachar D, Zuk R, Gazawi H, Reshef A, Sheinkman A, Klein E. Increased mitochondrial complex I activity in platelets of schizophrenic patients. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2:245–53.

Gardner A, Johansson A, Wibom R, Nennesmo I, Döbeln Uvon, Hagenfeldt L, et al. Alterations of mitochondrial function and correlations with personality traits in selected major depressive disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2003;76:55–68.

Gardner A, Salmaso D, Nardo D, Micucci F, Nobili F, Sanchez-Crespo A, et al. Mitochondrial function is related to alterations at brain SPECT in depressed patients. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:805–14.

Casademont J, Rodriguez-Santiago B, Miró O, Beato A, López S, Nunes V, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory chain in brain homogenates: activities in different brain areas in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:1–7.

Sanchez-Bahillo A, Bautista-Hernandez V, Barcia Gonzalez C, Bañon R, Luna A, Hirsch E, et al. Increased mRNA expression of cytochrome oxidase in dorsal raphe nucleus of depressive suicide victims. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:413–6.

Sousa RTde, Streck EL, Zanetti MV, Ferreira GK, Diniz BS, Brunoni AR, et al. Lithium increases leukocyte mitochondrial complex I activity in bipolar disorder during depressive episodes. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:245–50.

Gubert C, Stertz L, Pfaffenseller B, Panizzutti BS, Rezin GT, Massuda R, et al. Mitochondrial activity and oxidative stress markers in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and healthy subjects. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1396–402.

Merlo Pich M, Raule N, Catani L, Fagioli ME, Faenza I, Cocco L, et al. Increased transcription of mitochondrial genes for complex I in human platelets during ageing. FEBS Lett. 2004;558:19–22.

Merlo Pich M, Bovina C, Formiggini G, Cometti GG, Ghelli A, Parenti Castelli G, et al. Inhibitor sensitivity of respiratory complex I in human platelets: a possible biomarker of ageing. FEBS Lett. 1996;380:176–8.

Cooper JM, Daniel SE, Marsden CD, Schapira AHV. L-Dihydroxyphenylalanine and complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease brain. Mov Disord. 1995;10:295–7.

Maurer I, Zierz S, Möller H-J. Evidence for a mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defect in brains from patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:125–36.

Duke DC, Moran LB, Pearce RKB, Graeber MB. The medial and lateral substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease: mRNA profiles associated with higher brain tissue vulnerability. Neurogenetics. 2007;8:83–94.

Rasmussen UF, Krustrup P, Kjaer M, Rasmussen HN. Human skeletal muscle mitochondrial metabolism in youth and senescence: no signs of functional changes in ATP formation and mitochondrial oxidative capacity. Pflüg Arch. 2003;446:270–8.

Naydenov AV, MacDonald ML, Ongur D, Konradi C. Differences in lymphocyte electron transport gene expression levels between subjects with bipolar disorder and normal controls in response to glucose deprivation stress. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:555–64.

Fukuyama R, Hatanpää K, Rapoport SI, Chandrasekaran K. Gene expression of ND4, a subunit of complex I of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, is decreased in temporal cortex of brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Brain Res. 1996;713:290–3.

Rice MW, Smith KL, Roberts RC, Perez-Costas E, Melendez-Ferro M. Assessment of cytochrome c oxidase dysfunction in the substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area in schizophrenia. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100054.

Kim SH, Vlkolinsky R, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G. The reduction of NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase 24- and 75-kDa subunits in brains of patients with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2001;68:2741–50.

Whatley S, Curti D, Marchbanks R. Mitochondrial involvement in schizophrenia and other functional psychoses. Neurochem Res. 1996;21:995–1004.

Liang WS, Reiman EM, Valla J, Dunckley T, Beach TG, Grover A, et al. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with reduced expression of energy metabolism genes in posterior cingulate neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4441–6.

Sekar S, McDonald J, Cuyugan L, Aldrich J, Kurdoglu A, Adkins J, et al. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with altered expression of genes involved in immune response and mitochondrial processes in astrocytes. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:583–91.

Terni B, Boada J, Portero-Otin M, Pamplona R, Ferrer I. Mitochondrial ATP-synthase in the entorhinal cortex is a target of oxidative stress at stages I/II of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:222–33.

Vitali M, Venturelli E, Galimberti D, Benerini Gatta L, Scarpini E, Finazzi D. Analysis of the genes coding for subunit 10 and 15 of cytochrome c oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:1635–41.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tadafumi Kato, Brain Science Institute, RIKEN, Wako, Saitama, Japan, for sharing data. The authors thank Mercedes Armand-Ugon, Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain, for sharing data. The authors thank Tony Altar, Verge Genomics, San Francisco, USA, for sharing data. The work was funded by a Janssen Fellowship in Translational Neuroscience at Columbia University, New York awarded to L.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.J.J. receives royalties for commercial use of the C-SSRS from the Research Foundation of Mental Hygiene. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holper, L., Ben-Shachar, D. & Mann, J. Multivariate meta-analyses of mitochondrial complex I and IV in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease. Neuropsychopharmacol. 44, 837–849 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0090-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0090-0

This article is cited by

-

N1-methylation of adenosine (m1A) in ND5 mRNA leads to complex I dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Mitochondrial genetic variants associated with bipolar disorder and Schizophrenia in a Japanese population

International Journal of Bipolar Disorders (2023)

-

Brain mitochondrial diversity and network organization predict anxiety-like behavior in male mice

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Mitochondria play an essential role in the trajectory of adolescent neurodevelopment and behavior in adulthood: evidence from a schizophrenia rat model

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Antidepressants that increase mitochondrial energetics may elevate risk of treatment-emergent mania

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)