Abstract

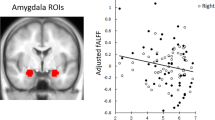

The significant link between stress and psychiatric disorders has prompted research on stress’s impact on the brain. Interestingly, previous studies on healthy subjects have demonstrated an association between perceived stress and amygdala volume, although the mechanisms by which perceived stress can affect brain function remain unknown. To better understand what this association entails at a functional level, herein, we explore the association of perceived stress, measured by the PSS10 questionnaire, with disseminated functional connectivity between brain areas. Using resting-state fMRI from 252 healthy subjects spanning a broad age range, we performed both a seed-based amygdala connectivity analysis (static connectivity, with spatial resolution but no temporal definition) and a whole-brain data-driven approach to detect altered patterns of phase interactions between brain areas (dynamic connectivity with spatiotemporal information). Results show that increased perceived stress is directly associated with increased amygdala connectivity with frontal cortical regions, which is driven by a reduced occurrence of an activity pattern where the signals in the amygdala and the hippocampus evolve in opposite directions with respect to the rest of the brain. Overall, these results not only reinforce the pathological effect of in-phase synchronicity between subcortical and cortical brain areas but also demonstrate the protective effect of counterbalanced (i.e., phase-shifted) activity between brain subsystems, which are otherwise missed with correlation-based functional connectivity analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

FSL software is available by the authors at https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FslInstallation and LEiDA scripts at GitHub (https://github.com/juanitacabral/LEiDA).

References

Fett A-KJ, Lemmers-Jansen ILJ, Krabbendam L. Psychosis and urbanicity: a review of the recent literature from epidemiology to neurourbanism. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32:232–41.

Gong Y, Palmer S, Gallacher J, Marsden T, Fone D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ Int. 2016;96:48–57.

Lederbogen F, Ulshoefer E, Peifer A, Fehlner P, Bilek E, Streit F, et al. No association between cardiometabolic risk and neural reactivity to acute psychosocial stress. NeuroImage-Clin. 2018;20:1115–22.

Ritchie H, Roser M. Urbanization. Our World in Data. 2018.

Cerqueira JJ, Mailliet F, Almeida OFX, Jay TM, Sousa N. The Prefrontal Cortex as a Key Target of the Maladaptive Response to Stress. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2781–7.

Magalhães R, Barrière DA, Novais A, Marques F, Marques P, Cerqueira J, et al. The dynamics of stress: a longitudinal MRI study of rat brain structure and connectome. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1998–2006.

Popoli M, Yan Z, McEwen BS, Sanacora G. The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:22–37.

Sousa N, Lukoyanov NV, Madeira MD, Almeida OFX, Paula-Barbosa MM. Reorganization of the morphology of hippocampal neurites and synapses after stress-induced damage correlates with behavioral improvement. Neuroscience 2000;97:253–66.

Yuen EY, Wei J, Liu W, Zhong P, Li X, Yan Z. Repeated Stress Causes Cognitive Impairment by Suppressing Glutamate Receptor Expression and Function in Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron 2012;73:962–77.

Koenig JI, Walker C-D, Romeo RD, Lupien SJ. Effects of stress across the lifespan. Stress 2011;14:475–80.

Kogler L, Müller VI, Chang A, Eickhoff SB, Fox PT, Gur RC, et al. Psychosocial versus physiological stress—Meta-analyses on deactivations and activations of the neural correlates of stress reactions. NeuroImage 2015;119:235–51.

Lucassen PJ, Pruessner J, Sousa N, Almeida OFX, Van Dam AM, Rajkowska G, et al. Neuropathology of stress. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:109–35.

Magalhães R, Novais A, Barrière DA, Marques P, Marques F, Sousa JC, et al. A Resting-State Functional MR Imaging and Spectroscopy Study of the Dorsal Hippocampus in the Chronic Unpredictable Stress Rat Model. J Neurosci. 2019;39:3640–50.

Novais A, Monteiro S, Roque S, Correia-Neves M, Sousa N. How age, sex and genotype shape the stress response. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;6:44–56.

Soares JM, Magalhães R, Moreira PS, Sousa A, Ganz E, Sampaio A, et al. A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Front Neurosci. 2016;10.

Soares JM, Marques P, Alves V, Sousa N. A hitchhiker’s guide to diffusion tensor imaging. Front Neurosci. 2013;7.

Sousa N. The dynamics of the stress neuromatrix. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:302–12.

Cabral J, Vidaurre D, Marques P, Magalhães R, Silva Moreira P, Miguel Soares J, et al. Cognitive performance in healthy older adults relates to spontaneous switching between states of functional connectivity during rest. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5135.

Esteban O, Markiewicz CJ, Blair RW, Moodie CA, Isik AI, Erramuzpe A, et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat Methods. 2018;16:111–6.

Lv H, Wang Z, Tong E, Williams LM, Zaharchuk G, Zeineh M, et al. Resting-State Functional MRI: Everything That Nonexperts Have Always Wanted to Know. Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:1390–9.

Bassett DS, Sporns O. Network neuroscience. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:353–64.

Biswal B, Zerrin Yetkin F, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar mri. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–41.

Menon SS, Krishnamurthy K. A Comparison of Static and Dynamic Functional Connectivities for Identifying Subjects and Biological Sex Using Intrinsic Individual Brain Connectivity. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5729.

Alonso Martínez S, Deco G, Ter Horst GJ, Cabral J. The Dynamics of Functional Brain Networks Associated With Depressive Symptoms in a Nonclinical Sample. Front Neural Circuits. 2020;14:570583.

Figueroa CA, Cabral J, Mocking RJT, Rapuano KM, Hartevelt TJ, Deco G, et al. Altered ability to access a clinically relevant control network in patients remitted from major depressive disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:2771–86.

Larabi DI, Renken RJ, Cabral J, Marsman J-BC, Aleman A, Ćurčić-Blake B. Trait self-reflectiveness relates to time-varying dynamics of resting state functional connectivity and underlying structural connectomes: Role of the default mode network. NeuroImage 2020;219:116896.

Arnold Anteraper S, Triantafyllou C, Sawyer AT, Hofmann SG, Gabrieli JD, Whitfield-Gabrieli S. Hyper-Connectivity of Subcortical Resting-State Networks in Social Anxiety Disorder. Brain Connect. 2014;4:81–90.

Chen JE, Lewis LD, Chang C, Tian Q, Fultz NE, Ohringer NA, et al. Resting-state “physiological networks”. NeuroImage 2020;213:116707.

Johnson FK, Delpech J-C, Thompson GJ, Wei L, Hao J, Herman P, et al. Amygdala hyper-connectivity in a mouse model of unpredictable early life stress. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:49.

Williams LM. Precision psychiatry: a neural circuit taxonomy for depression and anxiety. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:472–80.

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748–66.

Bryant RA. Post‐traumatic stress disorder: a state‐of‐the‐art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:259–69.

Melchior M, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Danese A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1119–29.

Pêgo JM, Sousa JC, Almeida O, Sousa N. Stress and the Neuroendocrinology of Anxiety Disorders. In: Stein MB, Steckler T, editors. Behavioral Neurobiology of Anxiety and Its Treatment, vol. 2, Berlin, Heidelberg:Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009. p. 97–118.

Hammen C. Stress and Depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319.

Carvalho AF, Firth J, Vieta E. Bipolar Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:58–66.

Kim EY, Miklowitz DJ, Biuckians A, Mullen K. Life stress and the course of early-onset bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;99:37–44.

Gispen-de Wied CC. Stress in schizophrenia: an integrative view. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:375–84.

Walker E, Mittal V, Tessner K. Stress and the Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis in the Developmental Course of Schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:189–216.

Avvenuti G, Leo A, Cecchetti L, Franco MF, Travis F, Caramella D, et al. Reductions in perceived stress following Transcendental Meditation practice are associated with increased brain regional connectivity at rest. Brain Cogn. 2020;139:105517.

Bergdahl J, Larsson A, Nilsson L-G, Ahlström KR, Nyberg L. Treatment of chronic stress in employees: subjective, cognitive and neural correlates. Scand J Psychol. 2005;46:395–402.

Kaul D, Schwab SG, Mechawar N, Matosin N. How stress physically re-shapes the brain: Impact on brain cell shapes, numbers and connections in psychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;124:193–215.

Taren AA, Gianaros PJ, Greco CM, Lindsay EK, Fairgrieve A, Brown KW, et al. Mindfulness meditation training alters stress-related amygdala resting state functional connectivity: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2015;10:1758–68.

Caetano I, Amorim L, Soares JM, Ferreira S, Coelho A, Reis J, et al. Amygdala size varies with stress perception. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;14:100334.

Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, Hoge EA, Dusek JA, Morgan L, et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5:11–7.

Archer JA, Lee A, Qiu A, Chen S-HA. Functional connectivity of resting-state, working memory and inhibition networks in perceived stress. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;8:186–201.

Jovanovic H, Perski A, Berglund H, Savic I. Chronic stress is linked to 5-HT1A receptor changes and functional disintegration of the limbic networks. Neuroimage 2011;55:1178–88.

Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Olaru M, Sugrue LP, Staffaroni AM, Delucchi KL, et al. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Training in Surgery: Additional Analysis of the Mindful Surgeon Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194108.

Soares JM, Sampaio A, Ferreira LM, Santos NC, Marques P, Marques F, et al. Stress Impact on Resting State Brain Networks. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e66500.

Soares JM, Sampaio A, Marques P, Ferreira LM, Santos NC, Marques F, et al. Plasticity of resting state brain networks in recovery from stress. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7.

Soares JM, Sampaio A, Ferreira LM, Santos NC, Marques F, Palha JA, et al. Stress-induced changes in human decision-making are reversible. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e131.

Taren AA, Gianaros PJ, Greco CM, Lindsay EK, Fairgrieve A, Brown KW, et al. Mindfulness Meditation Training and Executive Control Network Resting State Functional Connectivity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:674–83.

Wu J, Geng X, Shao R, Wong NML, Tao J, Chen L, et al. Neurodevelopmental changes in the relationship between stress perception and prefrontal-amygdala functional circuitry. NeuroImage-Clin. 2018;20:267–74.

Esteban O, Markiewicz CJ, Goncalves M, DuPre E, Kent JD, Salo T, et al. fMRIPrep (software). Zenodo; 2021.

Esteban O, Markiewicz CJ, Burns C, Goncalves M, Jarecka D, Ziegler E, et al. Nipype (software). Zenodo; 2020.

Gorgolewski K, Burns CD, Madison C, Clark D, Halchenko YO, Waskom ML, et al. Nipype: A Flexible, Lightweight and Extensible Neuroimaging Data Processing Framework in Python. Front Neuroinform. 2011;5.

Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. NeuroImage 2012;62:782–90.

Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 2004;23:S208–S219.

Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, Chappell M, Makni S, Behrens T, et al. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. NeuroImage 2009;45:S173–S186.

Rolls ET, Joliot M, Tzourio-Mazoyer N. Implementation of a new parcellation of the orbitofrontal cortex in the automated anatomical labeling atlas. NeuroImage 2015;122:1–5.

Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. NeuroImage 2002;15:273–89.

Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, Nichols TE. Permutation inference for the general linear model. NeuroImage 2014;92:381–97.

Xia M, Wang J, He Y. BrainNet Viewer: A Network Visualization Tool for Human Brain Connectomics. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68910.

Vohryzek J, Deco G, Cessac B, Kringelbach ML, Cabral J. Ghost Attractors in Spontaneous Brain Activity: Recurrent Excursions Into Functionally-Relevant BOLD Phase-Locking States. Front Syst Neurosci. 2020;14:20.

Lord L-D, Expert P, Atasoy S, Roseman L, Rapuano K, Lambiotte R, et al. Dynamical exploration of the repertoire of brain networks at rest is modulated by psilocybin. NeuroImage 2019;199:127–42.

Killgore WDS. Self-Reported Sleep Correlates with Prefrontal-Amygdala Functional Connectivity and Emotional Functioning. Sleep 2013;36:1597–608.

Johnstone T, van Reekum CM, Urry HL, Kalin NH, Davidson RJ. Failure to Regulate: Counterproductive Recruitment of Top-Down Prefrontal-Subcortical Circuitry in Major Depression. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8877–84.

Cahill L, Uncapher M, Kilpatrick L, Alkire MT, Turner J. Sex-Related Hemispheric Lateralization of Amygdala Function in Emotionally Influenced Memory: an fMRI Investigation. Learn Mem. 2004;11:261–6.

Kilpatrick LA, Zald DH, Pardo JV, Cahill LF. Sex-related differences in amygdala functional connectivity during resting conditions. NeuroImage 2006;30:452–61.

Cahill L. Sex-Related Influences on the Neurobiology of Emotionally Influenced Memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;985:163–73.

Cerqueira JJ, Almeida OFX, Sousa N. The stressed prefrontal cortex. Left? Right! Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:630–8.

Clark US, Miller ER, Hegde RR. Experiences of Discrimination Are Associated With Greater Resting Amygdala Activity and Functional Connectivity. Biol Psychiat-Cogn Neurosci Neuroimag. 2018;3:367–78.

Banks SJ, Eddy KT, Angstadt M, Nathan PJ, Phan KL. Amygdala–frontal connectivity during emotion regulation. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:303–12.

Marek S, Dosenbach NUF. The frontoparietal network: function, electrophysiology, and importance of individual precision mapping. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20:133–40.

Berboth S, Morawetz C. Amygdala-prefrontal connectivity during emotion regulation: a meta-analysis of psychophysiological interactions. Neuropsychologia 2021;153:107767.

Cerullo MA, Fleck DE, Eliassen JC, Smith MS, DelBello MP, Adler CM, et al. A longitudinal functional connectivity analysis of the amygdala in bipolar I disorder across mood states: A longitudinal functional connectivity analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:175–84.

Li M, Huang C, Deng W, Ma X, Han Y, Wang Q, et al. Contrasting and convergent patterns of amygdala connectivity in mania and depression: a resting-state study. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:53–58.

Magalhães R, Picó-Pérez M, Esteves M, Vieira R, Castanho TC, Amorim L, et al. Habitual coffee drinkers display a distinct pattern of brain functional connectivity. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:6589–98.

Kolassa I-T, Wienbruch C, Neuner F, Schauer M, Ruf M, Odenwald M, et al. Altered oscillatory brain dynamics after repeated traumatic stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:56.

García-Martínez B, Martínez-Rodrigo A, Fernández-Caballero A, Moncho-Bogani J, Alcaraz R. Nonlinear predictability analysis of brain dynamics for automatic recognition of negative stress. Neural Comput Applic. 2020;32:13221–31.

Fontenele AJ, de Vasconcelos NAP, Feliciano T, Aguiar LAA, Soares-Cunha C, Coimbra B, et al. Criticality between Cortical States. Phys Rev Lett. 2019;122:208101.

Beggs JM, Timme N. Being Critical of Criticality in the Brain. Front Physio. 2012;3.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by National funds, through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) [projects UIDB/50026/2020, UIDP/50026/2020, PTDC/MED-NEU/29071/2017]; by BIAL foundation [grants PT/FB/BL-2016-206, BIAL 30-16]; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian [contract grant P-139977]; and the European Commission (FP7) [contract HEALTH-F2-2010-259772]. Fellowship grants supported IC, LA, and AC through the FCT [grants number SFRH/BD/133006/2017, SFRH/BD/101398/2014, NORTE-08-5369-FSE-000041] from the Health Science program. JC is funded by FCT grant CEECIND/03325/2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: IC, NS. Methodology: IC, SF, JC, NS. Software: IC, SF, JC. Validation: IC, LA, TCC, CL, MPP, JC. Formal analysis: IC, SF, JC. Investigation: LA, TCC, AC, SF, CPN, JMS, NG, RS, JR, PMarques, PSM, AJR, PM, RM, MPP. Resources: AJR, NCS, PM, NS. Data Curation: AC, RM. Writing - Original Draft: IC. Writing—Review & Editing: JC, NS. Visualization: IC, JC, NS. Supervision: NS. Project administration: NS. Funding acquisition: AJR, NCS, PM, NS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Caetano, I., Ferreira, S., Coelho, A. et al. Perceived stress modulates the activity between the amygdala and the cortex. Mol Psychiatry 27, 4939–4947 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01780-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01780-8