Abstract

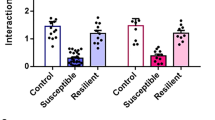

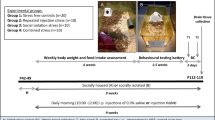

Chronic social isolation stress during adolescence induces susceptibility for neuropsychiatric disorders. Here we show that 5-week post-weaning isolation stress induces sex-specific behavioral abnormalities and neuronal activity changes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), basal lateral amygdala (BLA), and ventral tegmental area (VTA). Chemogenetic manipulation, optogenetic recording, and in vivo calcium imaging identify that the PFC to BLA pathway is causally linked to heightened aggression in stressed males, and the PFC to VTA pathway is causally linked to social withdrawal in stressed females. Isolation stress induces genome-wide transcriptional alterations in a region-specific manner. Particularly, the upregulated genes in BLA of stressed males are under the control of activated transcription factor CREB, and CREB inhibition in BLA normalizes gene expression and reverses aggressive behaviors. On the other hand, neuropeptide Hcrt (Hypocretin/Orexin) is among the top-ranking downregulated genes in VTA of stressed females, and Orexin-A treatment rescues social withdrawal. These results have revealed molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets for stress-related mental illness.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO public repository under accession code GSE198725.

References

Sanacora G, Yan Z, Popoli M. The stressed synapse 2.0: pathophysiological mechanisms in stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2022;23:86–103.

McEwen BS, Bowles NP, Gray JD, Hill MN, Hunter RG, Karatsoreos IN, et al. Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1353–63.

Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:651.

Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13.

Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Yonkers KA, McCullough JP, Keitner GI, et al. Gender differences in chronic major and double depression. J Affect Disord. 2000;60:1–11.

Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1044–8.

Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:959–92.

Yan Z, Rein B. Mechanisms of synaptic transmission dysregulation in the prefrontal cortex: pathophysiological implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01092-3.

Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–63.

Walker DM, Cunningham AM, Gregory JK, Nestler EJ. Long-term behavioral effects of post-weaning social isolation in males and females. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:66.

Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:434–45.

Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–57.

Wongwitdecha N, Marsden CA. Social isolation increases aggressive behaviour and alters the effects of diazepam in the rat social interaction test. Behav Brain Res. 1996;75:27–32.

Tan T, Wang W, Liu T, Zhong P, Conrow-Graham M, Tian X, et al. Neural circuits and activity dynamics underlying sex-specific effects of chronic social isolation stress. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108874.

Amiri S, Haj-Mirzaian A, Rahimi-Balaei M, Razmi A, Kordjazy N, Shirzadian A, et al. Co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive-like behaviors following adolescent social isolation in male mice; possible role of nitrergic system. Physiol Behav. 2015;145:38–44.

Van den Berg CL, Pijlman FT, Koning HA, Diergaarde L, Van Ree JM, Spruijt BM. Isolation changes the incentive value of sucrose and social behaviour in juvenile and adult rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;106:133–42.

Liu J, Dietz K, DeLoyht JM, Pedre X, Kelkar D, Kaur J, et al. Impaired adult myelination in the prefrontal cortex of socially isolated mice. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1621–3.

Han X, Wang W, Xue X, Shao F, Li N. Brief social isolation in early adolescence affects reversal learning and forebrain BDNF expression in adult rats. Brain Res Bull. 2011;86:173–8.

Wang YC, Ho UC, Ko MC, Liao CC, Lee LJ. Differential neuronal changes in medial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala and nucleus accumbens after postweaning social isolation. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217:337–51.

Pena CJ, Kronman HG, Walker DM, Cates HM, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, et al. Early life stress confers lifelong stress susceptibility in mice via ventral tegmental area OTX2. Science. 2017;356:1185–8.

Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW, et al. Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493:532–6.

Gold PW. The organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in depressive illness. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:32–47.

Fone KC, Porkess MV. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of post-weaning social isolation in rodents-relevance to developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1087–102.

Wang ZJ, Zhong P, Ma K, Seo JS, Yang F, Hu Z, et al. Amelioration of autism-like social deficits by targeting histone methyltransferases EHMT1/2 in Shank3-deficient mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:2517–33.

Wei J, Zhong P, Qin L, Tan T, Yan Z. Chemicogenetic restoration of the prefrontal cortex to amygdala pathway ameliorates stress-induced deficits. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:1980–90.

Rapanelli M, Tan T, Wang W, Wang X, Wang ZJ, Zhong P, et al. Behavioral, circuitry, and molecular aberrations by region-specific deficiency of the high-risk autism gene Cul3. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:1491–504.

Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation-a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–4.

Arruda-Carvalho M, Clem RL. Pathway-selective adjustment of prefrontal-amygdala transmission during fear encoding. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15601–9.

Wang W, Rein B, Zhang F, Tan T, Zhong P, Qin L, et al. Chemogenetic activation of prefrontal cortex rescues synaptic and behavioral deficits in a mouse model of 16p11.2 deletion syndrome. J Neurosci. 2018;38:5939–48.

Zhong P, Qin L, Yan Z. Dopamine differentially regulates response dynamics of PFC principal neurons and interneurons to optogenetic stimulation of VTA inputs. Cereb Cortex. 2020;30:4402–9.

Nelson RJ, Trainor BC. Neural mechanisms of aggression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:536–46.

Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:321–52.

Wu GY, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. Activity-dependent CREB phosphorylation: convergence of a fast, sensitive calmodulin kinase pathway and a slow, less sensitive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2808–13.

Boer U, Alejel T, Beimesche S, Cierny I, Krause D, Knepel W, et al. CRE/CREB-driven up-regulation of gene expression by chronic social stress in CRE-luciferase transgenic mice: reversal by antidepressant treatment. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e431.

Yin JC, Wallach JS, Del Vecchio M, Wilder EL, Zhou H, Quinn WG, et al. Induction of a dominant negative CREB transgene specifically blocks long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:49–58.

Valverde O, Mantamadiotis T, Torrecilla M, Ugedo L, Pineda J, Bleckmann S, et al. Modulation of anxiety-like behavior and morphine dependence in CREB-deficient mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1122–33.

Barrot M, Wallace DL, Bolanos CA, Graham DL, Perrotti LI, Neve RL, et al. Regulation of anxiety and initiation of sexual behavior by CREB in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8357–62.

Blendy JA. The role of CREB in depression and antidepressant treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1144–50.

Xie F, Li BX, Kassenbrock A, Xue C, Wang X, Qian DZ, et al. Identification of a potent inhibitor of CREB-mediated gene transcription with efficacious in vivo anticancer activity. J Med Chem. 2015;58:5075–87.

Li BX, Gardner R, Xue C, Qian DZ, Xie F, Thomas G, et al. Systemic inhibition of CREB is well-tolerated in vivo. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34513.

Franklin TB, Silva BA, Perova Z, Marrone L, Masferrer ME, Zhan Y, et al. Prefrontal cortical control of a brainstem social behavior circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:260–70.

Qin L, Ma K, Wang ZJ, Hu Z, Matas E, Wei J, et al. Social deficits in Shank3-deficient mouse models of autism are rescued by histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:564–75.

Kim CK, Yang SJ, Pichamoorthy N, Young NP, Kauvar I, Jennings JH, et al. Simultaneous fast measurement of circuit dynamics at multiple sites across the mammalian brain. Nat Methods. 2016;13:325–8.

Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300.

Gunaydin LA, Grosenick L, Finkelstein JC, Kauvar IV, Fenno LE, Adhikari A, et al. Natural neural projection dynamics underlying social behavior. Cell. 2014;157:1535–51.

Bariselli S, Tzanoulinou S, Glangetas C, Prevost-Solie C, Pucci L, Viguie J, et al. SHANK3 controls maturation of social reward circuits in the VTA. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:926–34.

Hung LW, Neuner S, Polepalli JS, Beier KT, Wright M, Walsh JJ, et al. Gating of social reward by oxytocin in the ventral tegmental area. Science. 2017;357:1406–11.

Kash TL, Pleil KE, Marcinkiewcz CA, Lowery-Gionta EG, Crowley N, Mazzone C, et al. Neuropeptide regulation of signaling and behavior in the BNST. Mol Cells. 2015;38:1–13.

Ji MJ, Zhang XY, Chen Z, Wang JJ, Zhu JN. Orexin prevents depressive-like behavior by promoting stress resilience. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:282–93.

Grippo AJ, Gerena D, Huang J, Kumar N, Shah M, Ughreja R, et al. Social isolation induces behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances relevant to depression in female and male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:966–80.

de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, et al. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:322–7.

Zelikowsky M, Hui M, Karigo T, Choe A, Yang B, Blanco MR, et al. The neuropeptide Tac2 controls a distributed brain state induced by chronic social isolation stress. Cell. 2018;173:1265–79.e19.

Mikics E, Guirado R, Umemori J, Toth M, Biro L, Miskolczi C, et al. Social learning requires plasticity enhanced by fluoxetine through prefrontal Bdnf-TrkB signaling to limit aggression induced by post-weaning social isolation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:235–45.

Toth M, Mikics E, Tulogdi A, Aliczki M, Haller J. Post-weaning social isolation induces abnormal forms of aggression in conjunction with increased glucocorticoid and autonomic stress responses. Horm Behav. 2011;60:28–36.

Senst L, Baimoukhametova D, Sterley TL, Bains JS. Sexually dimorphic neuronal responses to social isolation. Elife. 2016;5:e18726.

Pena CJ, Smith M, Ramakrishnan A, Cates HM, Bagot RC, Kronman HG, et al. Early life stress alters transcriptomic patterning across reward circuitry in male and female mice. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5098.

Neumann ID, Veenema AH, Beiderbeck DI. Aggression and anxiety: social context and neurobiological links. Front Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:12.

Aleyasin H, Flanigan ME, Russo SJ. Neurocircuitry of aggression and aggression seeking behavior: nose poking into brain circuitry controlling aggression. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018;49:184–91.

van Heukelum S, Tulva K, Geers FE, van Dulm S, Ruisch IH, Mill J, et al. A central role for anterior cingulate cortex in the control of pathological aggression. Curr Biol. 2021;31:2321–33.e5.

Yamamuro K, Yoshino H, Ogawa Y, Makinodan M, Toritsuka M, Yamashita M, et al. Social isolation during the critical period reduces synaptic and intrinsic excitability of a subtype of pyramidal cell in mouse prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:998–1010.

Murase S, Grenhoff J, Chouvet G, Gonon FG, Svensson TH. Prefrontal cortex regulates burst firing and transmitter release in rat mesolimbic dopamine neurons studied in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 1993;157:53–6.

Holly EN, Miczek KA. Ventral tegmental area dopamine revisited: effects of acute and repeated stress. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:163–86.

Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–73.

Zamarbide M, Mossa A, Munoz-Llancao P, Wilkinson MK, Pond HL, Oaks AW, et al. Male-specific cAMP signaling in the hippocampus controls spatial memory deficits in a mouse model of autism and intellectual disability. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:760–8.

Brundin L, Bjorkqvist M, Petersen A, Traskman-Bendz L. Reduced orexin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of suicidal patients with major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:573–9.

Johnson PL, Truitt W, Fitz SD, Minick PE, Dietrich A, Sanghani S, et al. A key role for orexin in panic anxiety. Nat Med. 2010;16:111–5.

Strawn JR, Pyne-Geithman GJ, Ekhator NN, Horn PS, Uhde TW, Shutter LA, et al. Low cerebrospinal fluid and plasma orexin-A (hypocretin-1) concentrations in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:1001–7.

Grafe LA, Cornfeld A, Luz S, Valentino R, Bhatnagar S. Orexins mediate sex differences in the stress response and in cognitive flexibility. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:683–92.

Murugan M, Jang HJ, Park M, Miller EM, Cox J, Taliaferro JP, et al. Combined social and spatial coding in a descending projection from the prefrontal cortex. Cell. 2017;171:1663–77.e16.

Lee CR, Chen A, Tye KM. The neural circuitry of social homeostasis: consequences of acute versus chronic social isolation. Cell. 2021;184:2794–5.

Matthews GA, Nieh EH, Vander Weele CM, Halbert SA, Pradhan RV, Yosafat AS, et al. Dorsal raphe dopamine neurons represent the experience of social isolation. Cell. 2016;164:617–31.

Ehrstrom M, Naslund E, Levin F, Kaur R, Kirchgessner AL, Theodorsson E, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of orexin A and effects on plasma insulin and glucagon in the rat. Regul Pept. 2004;119:209–12.

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaoqing Chen and Kaijie Ma for their excellent technical support. We also thank the support of the Genomics and Bioinformatics Core of the State University of New York at Buffalo. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-MH108842 and R01-MH126443 to ZY, R01-MH111872 to AP and K01-DA050908 to ZJW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZJW performed behavioral, immunohistochemical, biochemical, and molecular biological experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; TS performed DREADD experiments and analyzed data. JL and AP designed and performed calcium imaging experiments and analyzed data. PZ performed optogenetic and electrophysiological experiments and analyzed data. FY analyzed genomic data. KS performed some immunohistochemical experiments. FZ performed some behavioral and biochemical experiments. ZY designed experiments, supervised the project, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, ZJ., Shwani, T., Liu, J. et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms for differential effects of chronic social isolation stress in males and females. Mol Psychiatry 27, 3056–3068 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01574-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01574-y

This article is cited by

-

Circadian desynchronization disrupts physiological rhythms of prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons in mice

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

The PFC-LH-VTA pathway contributes to social deficits in IRSp53-mutant mice

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Social isolation and the brain: effects and mechanisms

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)