Abstract

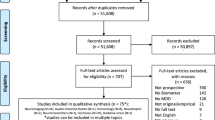

Research into major depressive disorder (MDD) is complicated by population heterogeneity, which has motivated the search for more homogeneous subtypes through data-driven computational methods to identify patterns in data. In addition, data on biological differences could play an important role in identifying clinically useful subtypes. This systematic review aimed to summarize evidence for biological subtypes of MDD from data-driven studies. We undertook a systematic literature search of PubMed, PsycINFO, and Embase (December 2018). We included studies that identified (1) data-driven subtypes of MDD based on biological variables, or (2) data-driven subtypes based on clinical features (e.g., symptom patterns) and validated these with biological variables post-hoc. Twenty-nine publications including 24 separate analyses in 20 unique samples were identified, including a total of ~ 4000 subjects. Five out of six biochemical studies indicated that there might be depression subtypes with and without disturbed neurotransmitter levels, and one indicated there might be an inflammatory subtype. Seven symptom-based studies identified subtypes, which were mainly determined by severity and by weight gain vs. loss. Two studies compared subtypes based on medication response. These symptom-based subtypes were associated with differences in biomarker profiles and functional connectivity, but results have not sufficiently been replicated. Four out of five neuroimaging studies found evidence for groups with structural and connectivity differences, but results were inconsistent. The single genetic study found a subtype with a distinct pattern of SNPs, but this subtype has not been replicated in an independent test sample. One study combining all aforementioned types of data discovered a subtypes with different levels of functional connectivity, childhood abuse, and treatment response, but the sample size was small. Although the reviewed work provides many leads for future research, the methodological differences across studies and lack of replication preclude definitive conclusions about the existence of clinically useful and generalizable biological subtypes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, et al. Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;109:38–46.

Sobocki P, Jönsson B, Angst J, Rehnberg C. Cost of depression in Europe. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9:87–98.

Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86.

Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1,162–478.

Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, Cuijpers P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:415–24.

Kessler RC, Broment EJ, de Jonge P, Shahly V, Wilcox M. The burden of depressive illness. Public Health Perspectives on Depressive Disorders. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2017, p 40.

Rush AJ. The varied clinical presentations of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 8):4–10.

Nandi A, Beard JR, Galea S. Epidemiologic heterogeneity of common mood and anxiety disorders over the lifecourse in the general population: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:31.

Goldberg D. The heterogeneity of ‘major depression’. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:226–8.

Wardenaar KJ, de Jonge P. Diagnostic heterogeneity in psychiatry: towards an empirical solution. BMC Med. 2013;11:201.

Fried EI, Nesse RM. Depression is not a consistent syndrome: an investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR???D study. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:96–102.

Monroe SM, Anderson SF. Depression: the shroud of heterogeneity. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2015;24:227–31.

Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008;455:894–902.

Hasler G. Pathophysiology of depression: do we have any solid evidence of interest to clinicians? World Psychiatry. 2010;9:155–61.

Simon GE, Perlis RH. Personalized medicine for depression: can we match patients with treatments? Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1445–55.

Ozomaro U, Wahlestedt C, Nemeroff CB. Personalized medicine in psychiatry: problems and promises. BMC Med. 2013;11:132.

Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Peyrot WJ, Abdellaoui A, Willemsen G, Hottenga J-J, et al. Polygenic dissection of major depression clinical heterogeneity. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:516–22.

Korte SM, Prins J, Krajnc AM, Hendriksen H, Oosting RS, Westphal KG, et al. The many different faces of major depression: it is time for personalized medicine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;753:88–104.

Bartova L, Berger A, Pezawas L. Is there a personalized medicine for mood disorders? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:121–6.

Nierenberg AA. Advancing the treatment of depression with personalized medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:e17.

Miller DB, O’Callaghan JP. Personalized medicine in major depressive disorder - opportunities and pitfalls. Metabolism 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2012.08.021.

Trivedi MH. Right patient, right treatment, right time: biosignatures and precision medicine in depression. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:237–8.

Kay DW, Garside RF, Beamish P, Roy JR. Endogenous and neurotic syndromes of depression: a factor analytic study of 104 cases. Clin Features Br J Psychiatry. 1969;115:377–88.

Pilowsky I, Levine S, Boulton DM. The classification of depression by numerical taxonomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1969;115:937–45.

Paykel ES. Classification of depressed patients: a cluster analysis derived grouping. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;118:275–88.

Andreasen NC, Grove WM. The classification of depression: traditional versus mathematical approaches. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:45–52.

Merikangas KR, Wicki W, Angst J. Heterogeneity of depression. Classification of depressive subtypes by longitudinal course. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:342–8.

Sullivan PF, Kessler RC, Kendler KS. Latent class analysis of lifetime depressive symptoms in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1398–406.

Orrù G, Pettersson-Yeo W, Marquand AF, Sartori G, Mechelli A. Using support vector machine to identify imaging biomarkers of neurological and psychiatric disease: a critical review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1140–52.

Van Loo HM, De Jonge P, Romeijn J-W, Kessler RC, Schoevers RA. Data-driven subtypes of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2012;10:156.

Marquand AF, Wolfers T, Mennes M, Buitelaar J, Beckmann CF. Beyond lumping and splitting: a review of computational approaches for stratifying psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1:433–47.

Ahmad A, Fröhlich H. Integrating heterogeneous omics data via statistical inference and learning techniques. Genom Comput Biol. 2016;2:e32.

Lin E, Hsien-Yuan L. Machine learning and systems genomicsapproaches for multi-omics data. Biomark Res. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-017-0082-y.

Baumeister H, Parker G. Meta-review of depressive subtyping models. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:126–40.

Kendell R, Jablensky A. Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:4–12.

Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine D, Quinn K, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–51.

Haro JM, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Bitter I, Demotes-Mainard J, Leboyer M, Lewis SW, et al. ROAMER: roadmap for mental health research in Europe. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23:1–14.

Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Brain disorders? Precisely. Science (80-). 2015;348:499–500.

The Prisma Group from, Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff JAD. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: the Prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–15.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Asberg M, Bertilsson L, Tuck D, Cronholm B, Sjöqvist F. Indoleamine metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressed patients before and during treatment with nortriptyline. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14:277–86.

Asberg M, Thoren P, Traskman L, Bertilsson L, Ringberger V. ‘Serotonin depression’–a biochemical subgroup within the affective disorders? Science (80-). 1976;191:478–80.

Gibbons RD, Davis JM. Consistent evidence for a biological subtype of depression characterized by low CSF monoamine levels. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;74:8–12.

Westenberg HGM, Verhoeven WMA. CSF monoamine metabolites in patients and controls: support for a bimodal distribution in major affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78:541–9.

Maas JW, Kocsis JH, Bowden CL, Davis JM, Redmond DE, Hanin I, et al. Pre-treatment neurotransmitter metabolites and response to imipramine or amitriptyline treatment. Psychol Med. 1982;12:37–43.

Åsberg M, Bertilsson L, Mårtensson B, Scalia‐Tomba G, Thorén P, Träskman‐Bendz P, et al. CSF monoamine metabolites in melancholia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1984;69:201–19.

Azorin JM, Raucoules D, Valli M, Levy C, Lancon C, Luccioni JM, et al. Plasma levels of 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol in depressed patients compared with normal controls. Neuropsychobiology. 1990;23:18–24.

Davis JM, Koslow SH, Gibbons RD, Maas JW, Bowden CL, Casper R, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and urinary biogenic amines in depressed patients and healthy controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:705–17.

Haroon E, Chen X, Li Z, Patel T, Woolwine BJ, Hu XP, et al. Increased inflammation and brain glutamate define a subtype of depression with decreased regional homogeneity, impaired network integrity, and anhedonia. Transl Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0241-4

Protzner AB, Kovacevic N, Cohn M, McAndrews MP. Characterizing functional integrity: intraindividual brain signal variability predicts memory performance in patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3009-12.2013.

Maes M, Cosyns P, Maes L, D’Hondt P, Schotte C. Clinical subtypes of unipolar depression: part I. A validation of the vital and nonvital clusters. Psychiatry Res. 1990;34:29–41.

Maes M, Maes L, Schotte C, Cosyns P. A clinical and biological validation of the DSM-III melancholia diagnosis in men: results of pattern recognition methods. J Psychiatr Res. 1992;26:183–96.

Schotte CKW, Maes M, Cluydts R, Cosyns P. Cluster analytic validation of the DSM melancholic depression. The threshold model: integration of quantitative and qualitative distinctions between unipolar depressive subtypes. Psychiatry Res. 1997;71:181–95.

Orsel S, Karadag H, Turkcapar H, Karaoglan Kahilogullari A. Diagnosis and classification subtyping of depressive disorders: comparison of three methods. Klin Psikofarmakol Bul. 2010;20:57–65.

Lamers F, de Jonge P, Nolen WA, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Beekman AT, et al. Identifying depressive subtypes in a large cohort study: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1582–9.

Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Mbarek H, Hottenga JJ, Boomsma DI, Penninx BWJH. The effect of FTO rs9939609 on major depression differs across MDD subtypes. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:960–2.

Lamers F, Rhebergen D, Merikangas KR, de Jonge P, Beekman ATF, Penninx BWJH. Stability and transitions of depressive subtypes over a 2-year follow-up. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2083–93.

Lamers F, Vogelzangs N, Merikangas KR, De Jonge P, Beekman ATF, Penninx BWJH. Evidence for a differential role of HPA-axis function, inflammation and metabolic syndrome in melancholic versus atypical depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:692–9.

Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Bot M, Drent ML, Penninx BWJH. Leptin dysregulation is specifically associated with major depression with atypical features: evidence for a mechanism connecting obesity and depression. Biol Psychiatry 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.023.

Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, Perry JRB, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science (80-). 2007;316:889–94.

Lamers F, Bot M, Jansen R, Chan MK, Cooper JD, Bahn S, et al. Serum proteomic profiles of depressive subtypes. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e851.

Bus BAA, Molendijk ML, Penninx B, Buitelaar JK, Prickaerts J, Elzinga BM, et al. Low serum BDNF levels in depressed patients cannot be attributed to individual depressive symptoms or symptom cluster. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15:561–9.

Bouveyron C, Girard S, Schmid C. High-dimensional data clustering. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2007;52:502–19.

Maglanoc LA, Landrø NI, Jonassen R, Kaufmann T, Cordova-Palomera A, Hilland E, et al. Data-driven clustering reveals a link between symptoms and functional brain connectivity in depression. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2019;4:16–26.

Feighner JP, Sverdlov L, Nicolau G, Noble JF. Cluster analysis of clinical data to identify subtypes within a study population following treatment with a new pentapeptide antidepressant. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;3:237–42.

Ballard ED, Yarrington JS, Farmer CA, Richards E, Machado-Vieira R, Kadriu B, et al. Characterizing the course of suicidal ideation response to ketamine. J Affect Disord. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.077.

Greicius M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;24:424–30.

Sundermann B, Olde lütke Beverborg M, Pfleiderer B. Toward literature-based feature selection for diagnostic classification: a meta-analysis of resting-state fMRI in depression. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00692.

Feder S, Sundermann B, Wersching H, Teuber A, Kugel H, Teismann H, et al. Sample heterogeneity in unipolar depression as assessed by functional connectivity analyses is dominated by general disease effects. J Affect Disord. 2017;222:79–87.

Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:603–11.

Price RB, Lane S, Gates K, Kraynak TE, Horner MS, Thase ME, et al. Parsing heterogeneity in the brain connectivity of depressed and healthy adults during positive mood. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:347–57.

Price RB, Gates K, Kraynak TE, Thase ME, Siegle GJ. Data-driven subgroups in depression derived from directed functional connectivity paths at rest. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2623–32.

Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, Dunlop K, Mansouri F, Meng Y, et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat Med. 2017;23:28–38.

Cheng Y, Xu J, Yu H, Nie B, Li N, Luo C, et al. Delineation of early and later adult onset depression by diffusion tensor imaging. PLoS One 2014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112307.

Yu C, Arcos-Burgos M, Licinio J, Wong ML. A latent genetic subtype of major depression identified by whole-exome genotyping data in a Mexican-American cohort. Transl Psychiatry 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.102.

Tokuda T, Yoshimoto J, Shimizu Y, Okada G, Takamura M, Okamoto Y, et al. Identification of depression subtypes and relevant brain regions using a data-driven approach. Sci Rep. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32521-z.

Tokuda T, Yoshimoto J, Shimizu Y, Okada G, Takamura M, Okamoto Y, et al. Multiple co-clustering based on nonparametric mixture models with heterogeneous marginal distributions. PLoS One 2017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186566.

Albert PR, Benkelfat C, Descarries L. The neurobiology of depression-revisiting the serotonin hypothesis. I. cellular and molecular mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2012;367:2378–81.

Lacasse JR, Leo J. Serotonin and depression: a disconnect between the advertisements and the scientific literature. PLoS Med. 2005;2:1211–6.

Maes M, Maes L, Schotte C, Vandewoude M, Martin M, D’Hondt P, et al. Clinical subtypes of unipolar depression: part III. Quantitative differences in various biological markers between the cluster-analytically generated nonvital and vital depression classes. Psychiatry Res. 1990;34:59–75.

Rodgers S, Grosse Holtforth M, Hengartner MP, Müller M, Aleksandrowicz AA, Rössler W, et al. Serum testosterone levels and symptom-based depression subtypes in men. Front Psychiatry 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00061.

Bot M, Chan MK, Jansen R, Lamers F, Vogelzangs N, Steiner J, et al. Serum proteomic profiling of major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e599.

Zhu X, Wang X, Xiao J, Zhong M, Liao J, Yao S. Altered white matter integrity in first-episode, treatment-naive young adults with major depressive disorder: a tract-based spatial statistics study. Brain Res. 2011;1369:223–9.

Koenigs M, Baskin-Sommers A, Zeier J, Newman JP. Investigating the neural correlates of psychopathy: a critical review. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:792–9.

van Loo HM, Wanders RBK, Wardenaar KJ, Fried EI. Problems with latent class analysis to detect data-driven subtypes of depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.202.

APA. Submit proposals for making changes to DSM–5. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/submit-proposals. Accessed 12 Dec 2017.

Kriegeskorte N, Simmons WK, Bellgowan PS, Baker CI. Circular analysis in systems neuroscience: the dangers of double dipping. Nat Neurosci. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2303

Liu Y, Hayes DN, Nobel A, Marron JS. Statistical significance of clustering for high-dimension, low-sample size data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103:1281–93.

Tibshirani R, Walther G, Hastie T. Estimating the number of data clusters via the gap statistic. Biostat. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9868.00293.

Kou J. Estimating the number of clusters via the GUD statistic. J Comput Graph Stat. 2014;23:403–17.

Lubke GH, Muthén B. Investigating population heterogeneity with factor mixture models. Psychol Methods. 2005;10:21–39.

Wardenaar KJ, Wanders RBK, ten Have M, de Graaf R, de Jonge P. Using a hybrid subtyping model to capture patterns and dimensionality of depressive and anxiety symptomatology in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2017;215:125–34.

Kapur S, Phillips AG, Insel TR. Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it? Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1174–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beijers, L., Wardenaar, K.J., van Loo, H.M. et al. Data-driven biological subtypes of depression: systematic review of biological approaches to depression subtyping. Mol Psychiatry 24, 888–900 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0385-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0385-5

This article is cited by

-

Olfactory genes affect major depression in highly educated, emotionally stable, lean women: a bridge between animal models and precision medicine

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

Parsing altered gray matter morphology of depression using a framework integrating the normative model and non-negative matrix factorization

Nature Communications (2023)

-

The genetic basis of major depressive disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Biological subtyping of psychiatric syndromes as a pathway for advances in drug discovery and personalized medicine

Nature Mental Health (2023)

-

Biomarkers of central and peripheral inflammation mediate the association between HIV and depressive symptoms

Translational Psychiatry (2023)