Abstract

Renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma were accepted as unique renal tumors in the late 1990s. Since their formal description, criteria for diagnosis have evolved and additional distinct tumor subtypes originally considered as one these two entities are now recognized. The last two decades have witnessed unprecedented interest in the spectrum of low grade oncocytic renal neoplasms in three specific areas: (1) histologic characterization of tumors with overlapping morphologic features between oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; (2) description of potentially unique entities within this spectrum, such as eosinophilic vacuolated tumor and low-grade oncocytic tumor; and (3) better appreciation of the association between a subset of low grade oncocytic tumors and hereditary renal neoplasia. While this important work has been academically rewarding, the proposal of several histologic entities with overlapping morphologic and immunophenotypic features (which may require esoteric adjunctive immunohistochemical and/or molecular techniques for confirmation) has created frustration in the diagnostic pathology and urology community as information evolves regarding classification within this spectrum of renal neoplasia. Pathologists, including genitourinary subspecialists, are often uncertain as to the “best practice” diagnostic approach to such tumors. In this review, we present a practical clinically relevant algorithmic approach to classifying tumors within the low grade oncocytic family of renal neoplasia, including a proposal for compressing terminology for evolving categories where appropriate without sacrificing prognostic relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1975, the histologic diversity of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), as described in the second series Armed Forces Institute of Pathology fascicle on “Tumors of the kidney, renal pelvis and ureter”, was merely acknowledged as “(RCC) has many faces” and accompanying histologic descriptions divided tumors into two major groups: “granular cell RCC” and “clear cell RCC”1. Clinicopathologic studies attempting to delineate prognostic differences between these granular and clear cell patterns typically failed as they both included what we now know to be many different entities, both benign and malignant. In 1976, Klein and Valensi2 described renal oncocytoma, creating awareness of histologically meaningful subtypes of adult renal neoplasia beyond RCC. A year later, Mancilla-Jiminez et al.3 outlined criteria for papillary RCC and reported an overall favorable survival compared to other subtypes. In the following 40 years, astute histological observations, often later validated by ultrastructural, cytogenetic, immunohistochemical, and/or molecular data, resulted in a considerable expansion of the histologic classification and spectrum of adult renal neoplasia. In the 2016 WHO classification of renal tumors, there were 16 types of adult renal epithelial neoplasia with 5 in the overall category of low grade renal oncocytic tumors4. Over the past 7–8 years, description of further distinct entities and subtypes of RCC, again validated by the identification of shared recurring molecular alterations, has helped narrow the proportion of tumors previously diagnosed as unclassified RCC at both the high-grade and low-grade end of the spectrum. In a series of 2021 publications by the Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS), providing a comprehensive update on renal neoplasia, including existing, “emerging”, and “provisional” renal entities5,6, 22 tumor types were considered, including 10 with overall low grade eosinophilic (oncocytic) morphology (Table 1).

Herein, we assess the current state of renal neoplasia knowledge regarding potentially significant histopathologic entities to be reported by surgical pathologists in routine clinical practice. In Table 2 we provide a historical perspective about the evolution of classifying renal oncocytic tumors over the past five decades. Based on increasing numbers of oncocytic tumors we see referred in consultation and feedback/questions received during courses and workshops on this topic, it has become clear that accurate histologic classification of tumors within this spectrum is a daunting task for even pathologists with considerable experience, particularly those who are up to date with the expanding literature. The many factors contributing to these challenges include: subtle histologic differences between the oncocytic tumor entities, the extreme rarity of some clinically significant subtypes, the variable classification strategies employed at different major academic centers, the practical utility in maintaining some contemporary immunohistochemical antibodies that are rarely utilized, the variable provision of clinical and family history, and the confusion as to when an “entity” becomes accepted for routine diagnosis. This constellation of problems has led to lack of a prescribed best practice diagnostic approach, particularly regarding when immunohistochemical and/or molecular work up is required for “standard of care” diagnosis.

Our goal is to provide a practical overview on the histopathologic classification of low grade oncocytic renal tumors using clinically relevant nomenclature (Table 3) and a systematic approach (Fig. 1). For this review, the term “low grade” is used to designate the spectrum of tumors with favorable biologic potential and/or histologic low-grade features, including categories that arose from further study of problematic cases with overlapping features between renal oncocytoma and chromophobe RCC, and refined understanding of some syndrome-associated RCCs. Oncocytic tumors included in the review are those composed predominantly of cells with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. We acknowledge that despite these clarifications, many tumors described in this review may have prominent nucleoli or moderate nuclear atypia or areas with variable clear cell morphology. This review also does not include a discussion of every possible renal tumor that may exhibit low grade eosinophilic morphology such as oncocytic angiomyolipoma, some translocation associated RCCs, thyroid-like follicular carcinoma of kidney, clear cell RCC, or “solid” papillary RCC with oncocytic features.

Oncocytoma, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and related emerging low-risk renal oncocytic neoplasia

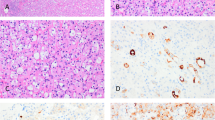

We typically recommend that pathologists should first evaluate cases to determine whether the histologic features are typical for a chromophobe RCC or a renal oncocytoma (based on stringent published criteria) (Fig. 1)7,8. Unfortunately, most descriptions of these two subtypes do not fully account for the complete histologic spectrum of low-risk oncocytic renal tumors encountered in routine practice, and many tumors simply do not precisely fit strict criteria for either renal oncocytoma or chromophobe RCC. We recommend first evaluating cases for definitive features of chromophobe RCC. In general, the presence of irregular hyperchromatic wrinkled nuclei (i.e., raisinoid), often with well-developed perinuclear halos, is sufficient for definitive classification as eosinophilic chromophobe RCC (Fig. 2A, B)9. Although the architecture in chromophobe RCC can be nested like oncocytoma, the presence of solid or broad alveolar architecture argues against oncocytoma. Other rare histologic features described in chromophobe RCC include microcystic architecture, cytoplasmic pigmentation, adenomatous glands, neuroendocrine-like architecture, and focal papillary pattern10,11,12,13,14. Evaluating the range of architectural features that both compound and/or help in the diagnosis of chromophobe RCC in resection specimens may be more difficult to assess in needle biopsies specimens, sometime restricting the confidence level of determining whether an oncocytic tumor is a chromophobe RCC versus an oncocytoma and other close differentials. Additional caution is warranted in core needle biopsies with greater attention to cyto-architectural features, applying appropriate, perhaps a wider panel of immunohistochemical stains, and possibly even providing a descriptive diagnosis listing reasonable differential diagnostic possibilities. The classic variant of chromophobe RCC has prominent cell membranes with cytoplasmic clearing that overlaps more with clear cell RCC than oncocytoma. When following strict published criteria, there are cases that do not have the distinct nuclear features of chromophobe RCC yet show a greater degree of architectural growth complexity and nuclear variability than typically allowed for renal oncocytoma. Features of these “difficult to classify” or “borderline” oncocytic tumors often include marked variation in the size of rounded nuclei, scattered cells with marked nuclear hyperchromasia (non-degenerative type), and macronucleoli (Fig. 2C, D). Mitoses in the (low grade) oncocytic tumors under discussion are almost non-existent, or extremely uncommon. Brisk mitotic activity in tumors with cytoplasmic eosinophilia would exclude them from this group of low grade tumors and should always merit investigations for alternative diagnoses. Unfortunately, based on our experience in consultation cases and anecdotal personal observations of reports of cases seen at multiple academic institutions, the classification of such borderline cases varies considerably between institutions. Possible strategies employed for classifying such cases include: (1) classify all morphologically “non-prototypical” chromophobe RCCs as oncocytoma, (2) classify cases with any degree of nuclear variability as chromophobe RCC, (3) use adjunctive immunophenotypic and/or molecular studies to classify into a definitive category, or (4) utilize a descriptive diagnostic category for borderline cases. We prefer adhering to rigid criteria for the diagnosis of both oncocytoma and chromophobe RCC; therefore, we favor utilizing a descriptive diagnostic category such as “oncocytic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential” for borderline cases. Lack of a consistent consensus approach for classification in this setting continues to create confusion for pathologists and urologists alike15.

Chromophobe RCC is best classified based on classic histologic features that include (A, B) irregular nuclear membranes and perinuclear clearing. Features of “borderline” or “difficult to classify” low grade oncocytic tumors, which we designate as “oncocytic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential”, include (C) more variability in nuclear size without the irregular nuclear membranes typical of chromophobe RCC, D often with more irregular chromatin distribution.

There have been numerous studies on the use of adjunctive immunohistochemistry and molecular techniques to subclassify oncocytic tumors within this family. While a comprehensive review is beyond our scope, some examples include immunohistochemistry for S100A1, HNF-1beta, FOXI1, and CK7 (among many others)15,16,17,18,19,20,21, and Hale’s colloidal iron stain22,23. Practically all adjunctive marker studies utilize the methodology of comparing immunophenotypes between two discreet categories as established for classic cases in the literature (i.e., renal oncocytoma and chromophobe RCC). As a specific example, studies are essentially reporting that “tumors classified as chromophobe RCC more typically have a CK7 positive immunophenotype”. Out of necessity, these studies are inherently biased by varied inclusion criteria for classification, as well as the distribution of prototypical and borderline cases evaluated. To our knowledge, there are no studies showing which adjunctive studies, if any, predict for metastatic disease; therefore, their utility for separating clinically benign tumors from their malignant counterparts remains unproven. In fact, it would be almost impossible to do such a study given that almost all of these tumors, including eosinophilic chromophobe RCC, follow an indolent clinical course after resection. The number of low-risk oncocytic renal neoplasms with well-documented aggressive behavior is incredibly small, such that most consultants have seen only rare examples in their career. Therefore, we generally recommend classification of these tumors primarily on histologic features. The only rare exception is that we do not classify the tumor as oncocytoma if it is strongly or relatively diffusely positive for CK 7, a scenario occasionally encountered in consultation cases where immunostaining has already been performed.

There have also been numerous studies on the underlying cytogenetic and molecular features of tumors within this family but mostly in chromophobe RCC, which are consistently associated with multiple chromosomal losses (e.g., 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 17, 21, and sex chromosomes)24,25 and highly variable molecular pathway changes that include alterations in mtDNA, TERT, p53, and PTEN (less commonly MTOR, NRAS, TSC1, and TSC2)24. Similar to immunohistochemical studies, molecular features are very heterogeneous and there is little data on correlation with outcome, particularly in histologically borderline cases. Although the problem of heterogeneity may be compounded in needle biopsy specimens, in current practice, like in immunohistochemistry, testing for molecular studies in best represented tissue material available usually yields satisfactory results; out of abundance of caution, we have advocated to our clinicians, particularly during multidisciplinary conferences and in an International Consortium of Urologic Disease Consultation providing recommendations to obtain 3 or more cores while procuring core biopsies to potentially overcome this issue26,27.

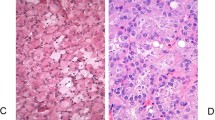

New descriptions of distinct renal neoplasms, most likely considered within the spectrum of chromophobe RCC by prior studies, are emerging and add further complexity to these diagnostic issues. The International Society of Urologic Pathology discussed some of the molecular aspects with immunohistochemical correlation of these tumors in a report in 201927. prior to the currently accepted nomenclature for these emerging tumors. These tumors have subtle but distinctive morphologic differences, as well as distinct immunophenotypic and molecular findings. One example described as “low-grade oncocytic tumor” has predominantly round nuclei but with some perinuclear clearing, an unusual immunophenotype (CD117 negative; CK7 positive), and frequent alterations in the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway- predominantly mutations of MTOR, TSC1, and TSC2 (Fig. 3A–C)28,29,30,31. Another distinctive renal tumor has been reported under the name “high-grade oncocytic renal tumor” but is more recently described as “eosinophilic vacuolated tumor” (Fig. 3D, E)32,33,34,35. These tumors have similar architectural features, but have nuclear enlargement with prominent nucleoli and distinctive intracytoplasmic vacuoles. They frequently express cathepsin-K, and have underlying mutations in MTOR, TSC1, and TSC2. In fact, both emerging renal neoplasms are very similar to a subset arising in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex36. It is not known how many of such tumors were included in the TCGA study of chromophobe RCC23. To date, all reported examples of these two tumors have followed an indolent clinical course with no metastases.

While “low grade oncocytic tumor (LOT)” has a characteristic (A) CK7 positive and (B) CD117 negative immunophenotype, it is histologically characterized by a low grade oncocytic morphology similar to eosinophilic RCC, often with edematous zones (C). “Eosinophilic vacuolated tumor (EVT)” has (D) distinct intracytoplasmic vacuoles and (E) greater nuclear variation (without chromophobe-like nuclear membrane irregularity).

While we fully recognize these emerging renal entities are distinctive, the increasing complexity and inconsistent criteria between academic institutions leaves many pathologists understandably frustrated by what constitutes “standard-of-care” work-up and diagnosis. The morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular diversity within the spectrum of low-risk oncocytic renal neoplasia could lead to increasing numbers of separate “entities” for each possible combination, creating a complex classification system difficult for urologists and oncologists to adopt (and for all pathologists to accurately recognize). Moreover, the current data suggest that all tumors within this spectrum have minimal risk for patient morbidity, questioning the clinical utility of subclassification (and its expense). One simplified approach to classifying tumors within this spectrum would be liberal use of the diagnosis “oncocytic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential”. A second descriptive term could be optionally utilized, where features point to a LOT or EVT tumor histology, such as “oncocytic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential [low-grade oncocytic tumor (LOT) type]” or “oncocytic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential [eosinophilic vacuolated tumor (EVT) type]” in academic settings with a desire to catalog cases for further study. For tumors with worrisome histologic features, such as vascular invasion or identifiable mitotic activity, another allowable descriptive term might be “RCC, low-risk oncocytic type”. Such a strategy would allow a diagnosis in the absence of expanded immunophenotypic or molecular techniques and would not impact clinical management. This proposed approach favors practical utility across all practice settings worldwide, possibly at the expense of academic advancement; however, it is our stance that the complexity of a more molecular and immunophenotypic approach to low-risk oncocytic renal neoplasia may prove unwieldy to urological practice.

Eosinophilic (oncocytic) tumors with hereditary connotations

Among the “oncocytic renal neoplasms of low malignant potential”, as discussed above, the diagnosis as specific entities may not have significant clinical implications5,6. However, there is a group of low-grade eosinophilic/oncocytic tumors that have a genetic/hereditary basis, where recognition is critical to ensure appropriate clinical consideration37. In some cases, the pathologist may be the first physician to suspect the syndrome. Such tumors include succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient RCC, a rare subset of low-grade fumarate hydratase (FH)-deficient RCC, Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome-associated RCC, and some rare cases of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)-associated RCC38,39,40,41. The presence of these tumors is often associated with increased risk of RCC and other syndrome specific extrarenal findings, necessitating genetic counseling/testing to ensure appropriate tumor screening for the patient and their affected family members37,39,40,41.

As discussed, when evaluating a renal tumor with exclusive or predominant oncocytic features, pathologists need to assess whether the tumor represents a renal oncocytoma or eosinophilic chromophobe RCC, the more common tumors in this differential. Once those diagnoses are excluded, mainly based on the morphology with some immunohistochemical support if required, it is essential to concentrate on the surrounding renal parenchyma and consider syndrome-associated renal neoplasia (Fig. 1). There may be morphological findings in the specimen that suggest a specific syndromic association in many cases. While early age at presentation may be the first clue, we recommend an electronic medical record search for any clinical/radiological evidence of bilateral renal involvement or a history of prior non-renal manifestations, which may include prior pathology specimens5,6.

Oncocytic renal tumors in a younger patient, particularly with a history/family history of prior pheochromocytoma or gastric GIST, requires careful search for the presence of intracytoplasmic pale eosinophilic to clear inclusions that may suggest a SDH-deficient tumor. “SDH-deficient RCC” mostly show low-grade cytology with only mild nuclear atypia, cells with abundant eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm, usually nested growth pattern, and frequently the presence of one or more pale eosinophilic or flocculent to completely clear cytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 4A). These inclusions correspond to giant mitochondria by ultrastructural examination. The presence of such findings, even when focal, will need immunohistochemical staining for SDHB38,42,43. Occasional SDH-deficient tumors may show focal, dominant, or even exclusive high-grade cytology. The cytoplasmic inclusions are seen even in such high-grade areas, although the finding may be only focal42,44,45,46. SDHB immunohistochemical staining is now available in many pathology laboratories, but if not available in-house, it may be prudent to send the case out for staining by a reference laboratory. Since SDHB is localized to mitochondria, positive/retained immunohistochemistry always shows granular cytoplasmic positivity. Weak, non-granular, diffuse cytoplasmic positivity is not regarded as retained reactivity44. Patients with SDH-deficient RCC are most often (75%) associated with mutation in SDHB, although rare cases with mutations in SDHD, SDHC and SHDA are described. In general, SDHB staining is lost in tumors with underlying mutations in any of these genes, while retained expression is seen in the internal control tissues (e.g., endothelial cells and inflammatory cells, Fig. 4B)45,46,47,48,49,50.

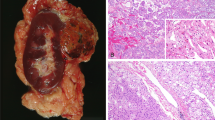

Presence of multifocal, oncocytic tumors in the nephrectomy specimen should raise the possibility of “BHD syndrome”. In addition to the grossly identifiable tumor nodules, the background kidney often shows numerous additional microscopic oncocytic nodules, cysts lined by oncocytic cells or small clusters of oncocytic cells percolating between non-neoplastic nephrons (Fig. 5A)51. Histologically, the tumors most frequently show hybrid oncocytic-chromophobe tumor like features, with larger areas resembling an oncocytoma (round monomorphic nuclei, often with prominent nucleoli, and eosinophilic cytoplasm), intermixed with nests of cells with relatively clear/fibrillary cytoplasm (Fig. 5B). The GUPS recommendations suggest that such tumors occurring in the setting of BHD syndrome be called “hybrid oncocytic chromophobe tumor”6. They recommend the term oncocytic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential for solitary tumors or tumors occurring in a sporadic setting. Pure oncocytoma or eosinophilic chromophobe RCC-like histology in some or all the tumor nodules is also not uncommon. Collectively, based on the gross tumors and the findings in the background kidney, the designation of renal oncocytosis is appropriate. There should be a comment in the report that renal oncocytosis is often associated with BHD syndrome, although many cases are still sporadic in nature. Immunohistochemistry is not useful in distinguishing BHD-associated oncocytosis from the much less common non-BHD oncocytosis. Clinical findings including the presence of bilateral lesions, cutaneous fibrofolliculomas or trichodiscomas, basilar pulmonary cysts, or history of spontaneous pneumothorax would be highly supportive of the syndromic association52,53,54.

“Low-grade Fumarate Hydratase (FH)-deficient tumors” are recently recognized renal oncocytoma-like or SDH-deficient-like tumors that need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of low-grade oncocytic tumors. In many of the 16 reported cases to date, histological appearance was similar to that of SDH-deficient tumors (Fig. 6A), with intracytoplasmic inclusions and/or vacuoles; although vacuoles are much less common in low-grade FH-deficient tumors (~25% have vacuoles) compared to SDH-deficient tumors where vacuoles are very commonly present38,39. In some instances, these low-grade tumors may contain some high-grade areas, with morphologic features highly suggestive of FH-deficient tumors (i.e., prominent nucleoli with peri-nucleolar halos). However, most pure eosinophilic tumors show no definite morphological suggestions indicative of the more common high-grade FH-deficient tumors38,39. There are usually no specific features in the non-neoplastic kidney that could suggest the diagnosis, although rarely oncocytic cell-lined cysts may be present. Since most of the cases of low grade FH-deficient RCC occur in the setting of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome, the potential diagnostic clues include presence of high-grade areas or separate high-grade typical tumors, clinical history of skin lesions (pathologically diagnosed leiomyomas or clinical skin nodules), uterine leiomyomas at young age, and an oncocytic renal tumor that looks like an SDH-deficient tumor but with retained SDHB immunohistochemical staining38,39,55,56. Immunohistochemically, loss of granular FH cytoplasmic staining is specific but not as sensitive (since some cases, particularly with missense mutations, may show retained staining), and increased 2SC expression is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis (Fig. 6B)57,58.

Fumarate hydratase-deficient low-grade oncocytic renal cell carcinoma (A) may closely resemble an SDH-deficient tumor. However, SDHB is retained in the tumor cells, whereas FH is completely lost. Diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity for 2SC in the tumor (B); this immunohistochemical stain is considered to be more sensitive than FH in these tumors.

Rare cases of “tuberous sclerosis complex-associated eosinophilic/oncocytic RCC” also need to be considered in the differential diagnosis in rare cases36,59,60,61,62,63. A subset of tumors shows features of “Eosinophilic Solid and Cystic (ESC) tumor” more commonly seen in a sporadic setting. These tumors are composed of a nested, tight acinar, solid, and cystic architecture comprised of cells with abundant finally granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, with occasional cells demonstrating Leishmania-like cytoplasmic stippling and multi-nucleation (Fig. 7A). Tumors are frequently CK 20 positive, but often not diffuse. It must be noted that some ESC tumors may be predominantly solid or may have only focal to negative CK 20 immunoreaction. In some cases, cysts lined by large cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, often with apocrine-type histology may also be present59,60,61,62,63. TSC-associated tumors almost always have associated angiomyolipomas in the surrounding kidney, which may be small and subtle (Fig. 7B), or in the resected lymph nodes.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)-associated low grade oncocytic tumor (A). Such tumors are not among the commoner type of RCC in TSC, and may show solid, nested, and cystic architecture in various combinations. Surrounding renal parenchyma (B) and accompanying lymph nodes often contain angiomyolipoma/s. Multiple renal cysts are also frequent.

The final diagnosis for most tumors associated with hereditary renal neoplasia will ultimately need genetic counseling/germ line testing, but histopathological evaluation can direct to a specific suspected syndrome in a significant proportion of such cases. Depending on the practice, academic/tertiary pathology practice, or after multidisciplinary discussion, mutational analysis may be performed to identify tumor or germline genes associated with hereditary neoplasia including VHL, MET, FH, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, MITF BHD, Folliculin, HRPT2, TSC1, TSC2, BAP1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 genes. We do not initiate germline testing given the need for informed consent, preferably under the guidance of a genetic counselor, but we provide a comment at the end of the histological diagnosis regarding the potential possibilities of the syndromic associations.

The American Urological Association Guidelines for renal mass and localized renal cancer were updated in 2021 with expanded indications for genetic counseling. Such counseling is now recommended for all patients ≤46 years of age with renal cancer, those with multifocal or bilateral renal masses, or whenever: (1) the personal or family history suggests a familial RCC syndrome; (2) there is a first or second-degree relative with a history of RCC or a known genetic or clinical diagnosis of a familial renal neoplastic syndrome, even if RCC has not been observed; or (3) whenever the pathology demonstrates histology suggestive of such a syndrome64. We clearly agree with these guidelines and encourage pathologists to be familiar with them.

Other renal tumors with oncocytic features that should be considered

After careful consideration of oncocytoma, chromophobe RCC, “borderline” tumors, and the spectrum of hereditary renal neoplasia, there are other subtypes of RCC that may rarely have overlapping histology and should be considered before the diagnosis of unclassified RCC is rendered (Fig. 1). MiTF-family/TFE-rearranged carcinomas with low-grade histology are very rare but do occasionally enter the differential diagnostic possibility among low-grade oncocytic tumors with nested features65,66. Biphasic histology, if present, is very suggestive of the diagnosis. Although TFE3 and TFEB immunohistochemistry is often used, we see many cases where use of these stains with conflicting results generates the consultation. We recommend that, if these tumors are suspected, confirmation by fluorescent in situ hybridization (studies) should be pursued. Other categories of tumors to consider include an unusual manifestation of a low-grade clear cell RCC with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm, a “solid” pattern of papillary RCC with eosinophilic cytoplasm, thyroid-like follicular carcinoma of the kidney, and oncocytic angiomyolipoma.

Summary of diagnostic approach and clinical implications

The spectrum of renal tumors with predominantly finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and low-grade nuclear features has grown and the pathological features of different diagnostic entities may have significant overlap. We have outlined a systematic approach for recognizing these tumors accurately in a clinically relevant fashion in routine surgical pathology practice. From the clinical perspective in low-grade oncocytic tumors, it is important to clarify that the tumors are organ confined and lack aggressive biologic features such as extrarenal extension, coagulative necrosis, high-grade nuclear atypia, sarcomatoid change or vascular-lymphatic invasion. This is particularly important for chromophobe RCC where these features have occasionally been associated with disease progression, metastasis, and death. Most other tumors discussed in this manuscript have low-risk or indolent biologic potential, such that their accurate diagnosis will allow for a management regimen based on their overall low-risk of progression. At present, treatment of metastatic chromophobe tumors remains a clinical conundrum. While multikinase inhibitors such as cabozantinib in combination with checkpoint inhibitors have a demonstrated encouraging activity in other subtypes such as papillary RCC, response rates are much more modest in chromophobe disease67,68. The presence of specific aforementioned features, in particular sarcomatoid and rhabdoid differentiation, may predispose to a greater responsiveness to immunotherapy69,70. The correct histologic diagnosis is important especially in renal tumors associated with hereditary neoplasms for surveillance and management of non-renal associated disease as well as genetic counseling for other family members as appropriate.

References

Bennington J BB. Tumors of the kidney, renal pelvis, and ureter. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Vol. 12. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (1975)

Klein MJ, Valensi QJ. Proximal tubular adenomas of kidney with so-called oncocytic features. A clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rarely reported neoplasm. Cancer 38, 906–914 (1976)

Mancilla-Jimenez R, Stanley RJ, Blath RA. Papillary renal cell carcinoma: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study of 34 cases. Cancer 38, 2469–2480 (1976).

Moch H, Amin M, Argani P, et al. Renal Cell Tumors Introduction. In: Moch H, Humphrey P, Ulbright T, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetic Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs., 4th ed. Lyon: Press, IARC, 2016. p. 14–17.

Trpkov K, Williamson SR, Gill AJ, Adeniran AJ, Agaimy A, Alaghehbandan R, et al. Novel, emerging and provisional renal entities: The Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) update on renal neoplasia. Mod Pathol 34, 1167–1184 (2021)

Trpkov K, Hes O, Williamson SR, Adeniran AJ, Agaimy A, Alaghehbandan R, et al. New developments in existing WHO entities and evolving molecular concepts: The Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) update on renal neoplasia. Mod Pathol 34, 1392–1424 (2021)

Amin MB, Crotty TB, Tickoo SK, Farrow GM. Renal oncocytoma: a reappraisal of morphologic features with clinicopathologic findings in 80 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 21, 1–12 (1997)

Amin MB, Paner GP, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Young AN, Stricker HJ, Lyles RH, et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: histomorphologic characteristics and evaluation of conventional pathologic prognostic parameters in 145 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 32, 1822–1834 (2008)

Tickoo SK, Amin MB. Discriminant nuclear features of renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Analysis of their potential utility in the differential diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol 110, 782–787 (1998)

Foix MP, Dunatov A, Martinek P, Mundó EC, Suster S, Sperga M, et al. Morphological, immunohistochemical, and chromosomal analysis of multicystic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, an architecturally unusual challenging variant. Virchows Arch 469, 669–678 (2016)

Michalova K, Tretiakova M, Pivovarcikova K, Alaghehbandan R, Perez Montiel D, Ulamec M, et al. Expanding the morphologic spectrum of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: A study of 8 cases with papillary architecture. Ann Diagn Pathol 44,151448 (2020)

Hes O, Vanecek T, Perez-Montiel DM, Alvarado CI, Hora M, Suster S, et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with microcystic and adenomatous arrangement and pigmentation--a diagnostic pitfall. Morphological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and molecular genetic report of 20 cases. Virchows Arch 446, 383–393 (2005)

Michal M, Hes O, Svec A, Ludvíková M. Pigmented microcystic chromophobe cell carcinoma: a unique variant of renal cell carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 2, 149–153 (1998)

Peckova K, Martinek P, Ohe C, Kuroda N, Bulimbasic S, Condom Mundo E, al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with neuroendocrine and neuroendocrine-like features. Morphologic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and array comparative genomic hybridization analysis of 18 cases and review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol 19, 261–268 (2015)

Molnar A, Horvath CA, Czovek P, Szanto A, Kovacs G. FOXI1 Immunohistochemistry Differentiates Benign Renal Oncocytoma from Malignant Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma. Anticancer Res 39, 2785–2790 (2019)

Tong K, Hu Z. FOXI1 expression in chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma: a study of The Cancer Genome Atlas transcriptome-based outlier mining and immunohistochemistry. Virchows Arch 478, 647–658 (2021)

Ng KL, Morais C, Bernard A, Saunders N, Samaratunga H, Gobe G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of immunohistochemical biomarkers that differentiate chromophobe renal cell carcinoma from renal oncocytoma. J Clin Pathol 69, 661–671 (2016)

Adley BP, Gupta A, Lin F, Luan C, Teh BT, Yang XJ. Expression of kidney-specific cadherin in chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma. Am J Clin Pathol, 126, 79–85 (2006)

Liu L, Qian J, Singh H, Meiers I, Zhou X, Bostwick DG. Immunohistochemical analysis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, renal oncocytoma, and clear cell carcinoma: an optimal and practical panel for differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol & Lab Med 131, 1290–1297 (2007)

Kuehn A, Paner GP, Skinnider BF, Cohen C, Datta MW, Young AN, et al. Expression analysis of kidney-specific cadherin in a wide spectrum of traditional and newly recognized renal epithelial neoplasms: diagnostic and histogenetic implications. Am J Surg Pathol 31,1528–1533 (2007)

Zheng G, Chaux A, Sharma R, Netto G, Caturegli P. LMP2, a novel immunohistochemical marker to distinguish renal oncocytoma from the eosinophilic variant of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol 94, 29–32 (2013)

Tickoo SK, Amin MB, Zarbo RJ. Colloidal iron staining in renal epithelial neoplasms, including chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: emphasis on technique and patterns of staining. Am J Surg Pathol 22, 419–424 (1998)

Cochand-Priollet B, Molinié V, Bougaran J, Bouvier R, Dauge-Geffroy MC, Deslignières S, et al. Renal chromophobe cell carcinoma and oncocytoma. A comparative morphologic, histochemical, and immunohistochemical study of 124 cases. Arch Pathol & Lab Med 121, 1081–1086 (1997)

Davis CF, Ricketts CJ, Wang M, Yang L, Cherniack AD, Shen H, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell, 26, 319–330 (2014)

Alaghehbandan R, Trpkov K, Tretiakova M, Luis AS, Rogala JD, Hes O. Comprehensive Review of Numerical Chromosomal Aberrations in Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma Including Its Variant Morphologies. Adv Anat Pathol 28, 8–20 (2021)

Jewett M, Volpe A, Evans A, Kuroda N, Reuter VE, Colecchia M, et al. Renal Tumour Biopsy: Indications, Technique, Safety, Accuracy/Results and Impact on Treatment Decision-making. In: Desai M, Sanchez-Salas R, editors. Image-Guided Therapy in Urology. Paris, France: ICUD-EAU Press (2016).

Williamson SR, Gill AJ, Argani P, Chen YB, Egevad L, Kristiansen G, et al. Report From the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consultation Conference on Molecular Pathology of Urogenital Cancers: III: Molecular Pathology of Kidney Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 44, e47–e65 (2020)

Morini A, Drossart T, Timsit MO, Sibony M, Vasiliu V, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, et al. Low-grade oncocytic renal tumor (LOT): mutations in mTOR pathway genes and low expression of FOXI1. Mod Pathol 35, 352–360 (2022)

Kapur P, Gao M, Zhong H, Chintalapati S, Mitui M, Barnes SD, et al. Germline and sporadic mTOR pathway mutations in low-grade oncocytic tumor of the kidney. Mod Pathol 35, 333–343 (2022)

Trpkov K, Williamson SR, Gao Y, Martinek P, Cheng L, Sangoi AR, et al. Low-grade oncocytic tumour of kidney (CD117-negative, cytokeratin 7-positive): a distinct entity? Histopathology 75, 174–184 (2019)

Guo Q, Liu N, Wang F, Guo Y, Yang B, Cao Z, et al. Characterization of a distinct low-grade oncocytic renal tumor (CD117-negative and cytokeratin 7-positive) based on a tertiary oncology center experience: the new evidence from China. Virchows Arch 478, 449–458 (2021)

Farcaş M, Gatalica Z, Trpkov K, Swensen J, Zhou M, Alaghehbandan R, et al. Eosinophilic vacuolated tumor (EVT) of kidney demonstrates sporadic TSC/MTOR mutations: next-generation sequencing multi-institutional study of 19 cases. Mod Pathol 35, 344–351 (2022)

Chen Y-B, Mirsadraei L, Jayakumaran G, Al-Ahmadie HA, Fine SW, Gopalan A, et al. Somatic Mutations of TSC2 or MTOR Characterize a Morphologically Distinct Subset of Sporadic Renal Cell Carcinoma With Eosinophilic and Vacuolated Cytoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol 43, 121–131 (2019)

He H, Trpkov K, Martinek P, Isikci OT, Maggi-Galuzzi C, Alaghehbandan R, et al. “High-grade oncocytic renal tumor”: morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 14 cases. Virchows Arch 473, 725–738 (2018)

Kapur P, Gao M, Zhong H, Rakheja D, Cai Q, Pedrosa I, et al. Eosinophilic Vacuolated Tumor of the Kidney: A Review of Evolving Concepts in This Novel Subtype With Additional Insights From a Case With MTOR Mutation and Concomitant Chromosome 1 Loss. Adv Anat Pathol 28, 251–257 (2021)

Guo J, Tretiakova MS, Troxell ML, Osunkoya AO, Fadare O, Sangoi AR, et al. Tuberous sclerosis-associated renal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 separate carcinomas in 18 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 38, 1457–1467 (2014)

Maher ER. Hereditary renal cell carcinoma syndromes: diagnosis, surveillance and management. World J Urol 36, 1891–1898 (2018)

Smith SC, Sirohi D, Ohe C, McHugh JB, Hornick JL, Kalariya J, et al. A distinctive, low-grade oncocytic fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma, morphologically reminiscent of succinate dehydrogenase-deficient renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology 71, 42–52 (2017)

Hamza A, Sirohi D, Smith SC, Amin MB. Low-grade Oncocytic Fumarate Hydratase-deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma: An Update on Biologic Potential, Morphologic Spectrum, and Differential Diagnosis With Other Low-grade Oncocytic Tumors. Adv Anat Pathol 28, 396–407 (2021)

Kryvenko ON, Jorda M, Argani P, Epstein JI Diagnostic approach to eosinophilic renal neoplasms. Arch Pathol & Lab Med 138, 1531–1541 (2014)

Trpkov K, Hes O. New and emerging renal entities: a perspective post-WHO 2016 classification. Histopathology 74, 31–59 (2019)

Gill A, Amin M, Smith SC, Šedivcová M, Tan PH, Agaimy A, et al. SDH Defficient Renal Cell Carcinoma. In: Moch H, Humphrey P, Ulbright T, et al. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetic Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs., 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press (2016) p. 35–36.

Gupta S, Menon S, Raghunathan A, Herrera-Hernandez L, Jimenez RE, Cheville JC. Do We Have Sufficient Evidence to Define Prognosis for “Low-grade” Fumarate Hydratase-deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma? Adv Anat Pathol (2022).

Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, Clarkson A, Muljono A, Meyer-Rochow GY, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD in paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol 41, 805–814 (2010)

Fuchs TL, Maclean F, Turchini J, Vargas AC, Bhattarai S, Agaimy A, et al. Expanding the clinicopathological spectrum of succinate dehydrogenase-deficient renal cell carcinoma with a focus on variant morphologies: a study of 62 new tumors in 59 patients. Mod Pathol (2021)

Cimadamore A, Cheng L, Scarpelli M, Massari F, Mollica V, Santoni M, et al. Towards a new WHO classification of renal cell tumor: what the clinician needs to know-a narrative review. Transl Androl Urol 10, 1506–1520 (2021)

Wilczek Y, Sachdeva A, Turner H, Veeratterapillay R. SDH-deficient renal cell carcinoma: a clinicopathological analysis highlighting the role of genetic counselling. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 103, e20–e22 (2021)

Kennedy JM, Wang X, Plouffe KR, Dhanasekaran SM, Hafez K, Palapattu GS, et al. Clinical and morphologic review of 60 hereditary renal tumors from 30 hereditary renal cell carcinoma syndrome patients: lessons from a contemporary single institution series. Med Oncol 36, 74 (2019).

Carlo MI, Hakimi AA, Stewart GD, Bratslavsky G, Brugarolas J, Chen YB, et al. Familial Kidney Cancer: Implications of New Syndromes and Molecular Insights. Eur Urol 76, 754–764 (2019)

Agaimy A, Hartmann A. Uncovering Hereditary Tumor Syndromes: Emerging Role of Surgical Pathology. Semin Diagn Pathol, 35, 154–160 (2018)

Tickoo SK, Reuter VE, Amin MB, Srigley JR, Epstein JI, Min KW, et al. Renal oncocytosis: a morphologic study of fourteen cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1094–1101.

Steinlein OK, Ertl-Wagner B, Ruzicka T, Sattler EC. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: an underdiagnosed genetic tumor syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 16, 278–283 (2018)

Adamy A, Lowrance WT, Yee DS, Chong KT, Bernstein M, Tickoo SK, et al. Renal oncocytosis: management and clinical outcomes. J Urol 185, 795–801 (2011)

Menko FH, van Steensel MAM, Giraud S, Friis-Hansen L, Richard S, Ungari S, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol 10, 1199–1206 (2009)

Trpkov K, Hes O, Agaimy A, Bonert M, Martinek P, Magi-Galluzzi C, et al. Fumarate Hydratase-deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma Is Strongly Correlated With Fumarate Hydratase Mutation and Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 40, 865–875 (2016)

Linehan WM, Pinto PA, Bratslavsky G, Pfaffenroth E, Merino M, Vocke CD, et al. Hereditary kidney cancer: unique opportunity for disease-based therapy. Cancer 115, 2252–2261 (2009)

Chen YB, Brannon AR, Toubaji A, Dudas ME, Won HH, Al-Ahmadie HA, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome-associated renal cancer: recognition of the syndrome by pathologic features and the utility of detecting aberrant succination by immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol 38, 627–637 (2014)

Buelow B, Cohen J, Nagymanyoki Z, Frizzell N, Joseph NM, McCalmont T, et al. Immunohistochemistry for 2-Succinocysteine (2SC) and Fumarate Hydratase (FH) in Cutaneous Leiomyomas May Aid in Identification of Patients With HLRCC (Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome). Am J Surg Pathol 40, 982–988 (2016)

Yang P, Cornejo KM, Sadow PM, Cheng L, Wang M, Xiao Y, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Surg Pathol 38, 895–909 (2014)

Gupta S, Lohse CM, Rowsey R, McCarthy MR, Shen W, Herrera-Hernandez L, et al. Renal Neoplasia in Polycystic Kidney Disease: An Assessment of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-associated Renal Neoplasia and PKD1/TSC2 Contiguous Gene Deletion Syndrome. Eur Urol (2021)

Henske EP, Cornejo KM, Wu C-L. Renal Cell Carcinoma in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Genes (Basel) 12 (2021)

Trnka P, Kennedy SE. Renal tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Nephrol 36, 1427–1438 (2021)

Verkarre V, Morini A, Denize T, Ferlicot S, Richard S. [Hereditary kidney cancers: The pathologist’s view in 2020]. Ann Pathol 40, 148–167 (2020)

Campbell SC, Clark PE, Chang SS, Karam JA, Souter L, Uzzo RG. Renal Mass and Localized Renal Cancer: Evaluation, Management, and Follow-Up: AUA Guideline: Part I. J Urol 206, 199–208 (2021)

Wei S, Testa JR, Argani P. A review of neoplasms with MITF/MiT family translocations. Histol Histopathol (2022).

Argani P. Translocation carcinomas of the kidney. Genes Chromosomes Cancer (2021).

Pal SK, McGregor B, Suárez C, Tsao CK, Kelly W, Vaishampayan U, et al. Cabozantinib in Combination With Atezolizumab for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results From the COSMIC-021 Study. J Clin Oncol 39, 3725–3736 (2021)

Lee C-H, Voss MH, Carlo MI, Chen, YB, Reznik E, Knezevic A, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib in patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Results of a phase 2 trial. J Clin Oncol 39, 4509 (2021)

Tannir NM, Signoretti S, Choueiri TK, McDermott DF, Motzer RJ, Flaifel A, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in First-line Treatment of Patients with Advanced Sarcomatoid Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 27, 78–86 (2021)

Bakouny Z, Braun DA, Shukla SA, Pan W, Gao X, Hou Y, et al. Integrative molecular characterization of sarcomatoid and rhabdoid renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun 12, 808 (2021)

Jaffe RH. Adenolymphoma (Oncocytoma) of Parotid Gland. Am J Cancer 16, 1415–1423 (1932)

Zippel J. Zur Kenntnis der Onkocyten. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med 308, 360–382 (1941)

MacLennan GT, Cheng L. Five decades of urologic pathology: the accelerating expansion of knowledge in renal cell neoplasia. Hum Pathol 95, 24–45 (2020)

Bannasch P, Schacht U, Storch E. [Morphogenesis and micromorphology of epithelial tumors of the kidney of nitrosomorpholine intoxicated rats. I. Induction and histology (author’s transl)]. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol 81, 311–331 (1974)

Engel U, Horn T, Nielsen OS, Olsen JH. Renal oncocytoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A 95, 107–111 (1987)

Jockle GA, Toker C, Shamsuddin AM. Metastatic renal oncocytic neoplasm with benign histologic appearance. Urology 30, 79–81 (1987)

Psihramis KE, Goldberg SD. Flow cytometric analysis of cellular deoxyribonucleic acid content of nine renal oncocytomas. Urology 38, 310–313 (1991)

Lieber MM, Tomera KM, Farrow GM. Renal oncocytoma. J Urol 125, 481–485 (1981)

Neisius D, Braedel HU, Schindler E, Hoene E, Alloussi S. Computed tomographic and angiographic findings in renal oncocytoma. Br J Radiol 61, 1019–1025 (1988)

Spring DB, Ulirsch RC, Starke WR, Brown SJ. Renal oncocytoma followed for eighteen years without resection. Urology 26, 389–392 (1985)

Thoenes W, Störkel S, Rumpelt HJ. Human chromophobe cell renal carcinoma. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 48, 207–217 (1985)

Thoenes W, Störkel S, Rumpelt HJ, Moll R, Baum HP, Werner S. Chromophobe cell renal carcinoma and its variants--a report on 32 cases. J Pathol 155, 277–287 (1988)

Crotty TB, Farrow GM, Lieber MM. Chromophobe cell renal carcinoma: clinicopathological features of 50 cases. J Urol 154, 964–967 (1995)

Kovacs A, Kovacs G. Low chromosome number in chromophobe renal cell carcinomas. Genes, Chromosom & Cancer 4, 267–268 (1992)

Störkel S, Eble JN, Adlakha K, Amin MB, Blute ML, Bostwick DG, et al. Classification of renal cell carcinoma: Workgroup No. 1. Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Cancer 80, 987–989 (1997)

Weirich G, Glenn G, Junker K, Merino M, Störkel S, Lubensky I, et al. Familial renal oncocytoma: clinicopathological study of 5 families. J Urol 160, 335–340 (1998)

Pavlovich CP, Walther MM, Eyler RA, Hewitt SM, Zbar B, Linehan WM, et al. Renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 26, 1542–1552 (2002)

Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, Egevad L, Epstein JI, Grignon D, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 37, 1469–1489 (2013)

Schreiner A, Daneshmand S, Bayne A, Countryman G, Corless CL, Troxell ML. Distinctive morphology of renal cell carcinomas in tuberous sclerosis. Int J Surg Pathol 18, 409–418 (2010)

Trpkov K, Hes O, Bonert M, Lopez JI, Bonsib SM, Nesi G et al. Eosinophilic, Solid, and Cystic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Clinicopathologic Study of 16 Unique, Sporadic Neoplasms Occurring in Women. Am J Surg Pathol 40, 60–71 (2016)

Gill AJ, Hes O, Papathomas T, Šedivcová M, Tan PH, Agaimy A, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient renal carcinoma: a morphologically distinct entity: a clinicopathologic series of 36 tumors from 27 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 38, 1588–1602 (2014)

Gill AJ, Pachter NS, Chou A, Young B, Clarkson A, Tucker KM, et al. Renal tumors associated with germline SDHB mutation show distinctive morphology. Am J Surg Pathol 35, 1578–1585 (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MBA, JKM and SKT performed study concept and design, provided acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of published literature, and performed writing; MBA, JKM, SCC, SP, GM and SKT performed review and revision of the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MBA is the Medical Director of the West Division of LabCorp. The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amin, M.B., McKenney, J.K., Martignoni, G. et al. Low grade oncocytic tumors of the kidney: a clinically relevant approach for the workup and accurate diagnosis. Mod Pathol 35, 1306–1316 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01108-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01108-5

This article is cited by

-

mTOR eosinophilic renal cell carcinoma: a distinctive tumor characterized by mTOR mutation, loss of chromosome 1, cathepsin-K expression, and response to target therapy

Virchows Archiv (2023)

-

Evaluation of an institutional series of low-grade oncocytic tumor (LOT) of the kidney and review of the mutational landscape of LOT

Virchows Archiv (2023)