Abstract

Concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment have led to interest in de-escalating treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). This article reviews the epidemiology, natural history, and current treatment options for DCIS and discusses ongoing efforts to further de-escalate treatment for these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is now well recognized that term “ductal carcinoma in situ” (DCIS) encompasses a heterogeneous group of lesions clinically, radiographically, histologically, immunophenotypically, and at the molecular level [1, 2]. If left untreated, some cases of DCIS will progress to invasive breast cancer whereas some, perhaps even the majority among certain types, will not [3]. For many years, a major goal of clinical research has been to distinguish patients with DCIS who are more likely to progress to invasive cancer and who, in turn, require more treatment, from those in whom the lesion is unlikely to progress and who require less treatment, or perhaps even no treatment beyond the diagnostic biopsy.

More recently, the management of patients with DCIS has come under even greater scrutiny amidst concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment [4,5,6,7,8], particularly at a time when de-escalation of local and systemic therapy for patients with invasive breast cancer is becoming increasingly common [9,10,11,12,13]. The purpose of this article, therefore, is to review the issues related to de-escalation of therapy for patients with DCIS.

Epidemiology and natural history

Most cases of DCIS in current clinical practice are asymptomatic and present as microcalcifications detected on screening mammograms. The impact of mammographic screening on the number of DCIS cases detected over the last several decades has been dramatic. For example, there was an almost ninefold increase in the age-adjusted incidence of DCIS in 2007 relative to 1997 [14]. DCIS currently accounts for ~20–25% of newly diagnosed breast “cancers” with over 60,000 new cases each year in the U.S. [6, 8]. One major question of clinical concern is: how much of this represents overdiagnosis (i.e., lesions that are identified but are biologically innocuous and will never harm the patient)?

DCIS is found at autopsy in up to 14.7% of women dying from other causes (the median prevalence in these studies is 8.9%) [3, 15] and in 0.1–1.1% of women undergoing reduction mammoplasty [16]. These autopsy and reduction mammoplasty studies undoubtedly underestimate the prevalence of DCIS in the population because of the limited sampling of breast tissue in these studies. Therefore, the true prevalence of DCIS in the general population is unknown.

The natural history of DCIS is poorly defined. A few, very small, retrospective reviews of surgical breast biopsies that were originally diagnosed as benign but in which DCIS was found on subsequent histologic review have been used to gain insight into the natural history of this lesion [3, 17,18,19,20] (Table 1). Because these biopsies were initially interpreted as benign, the patients received no treatment beyond the diagnostic surgical excision. However, it is important to note that in these cases, neither the extent of the lesion nor the adequacy of excision were known. In these studies, the reported frequency of subsequent invasive breast cancer ranged from 20 to 53%. These data indicate that if left untreated, some but not all DCIS lesions will progress to invasive breast cancer and that DCIS is, therefore, best regarded as a non-obligate precursor to invasive breast cancer. However, the proportion of DCIS cases that will progress to invasive cancer among the small, mammographically-detected lesions often encountered in current clinical practice is unknown.

Current treatment

Since DCIS poses no threat to life, the major purpose of treatment is to prevent the development of an invasive breast cancer (i.e., prophylactic treatment). In current clinical practice there are three main treatment options for DCIS: mastectomy, breast conserving surgery followed by radiation therapy, and breast conserving surgery alone. Any of these may be accompanied by adjuvant endocrine therapy [21]. In recent years, the combination of breast conserving surgery followed by radiation therapy has become the most frequently used treatment approach to women with DCIS. It is important to note that none of these treatment options offers a survival advantage over the others.

Until the early 1990s, mastectomy was the standard treatment for women with DCIS. However, as increasing numbers of patients with invasive breast cancer were being managed with breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy rather than mastectomy in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it seemed paradoxical to treat patients with DCIS with mastectomy while offering patients with invasive breast cancer the option of breast conserving therapy. No randomized clinical trial has ever compared mastectomy to breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy in women with DCIS. However, four randomized clinical trials have compared breast conserving surgery with radiation therapy to breast conserving surgery alone. A meta-analysis of these four trials from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists Collaborative Group demonstrated that the addition of radiation therapy to breast conserving surgery reduced the risk of local recurrence by ~50%, and further, that there was no subgroup of patients with DCIS that did not benefit from the addition of radiation therapy [22]. A subsequent randomized clinical trial from the NSABP (NSABP B24) demonstrated that the addition of tamoxifen to the combination of breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy reduced the risk of local recurrence by ~30% [23], and that the benefit of tamoxifen was limited to women whose DCIS was estrogen receptor (ER) positive [24]. Other studies have shown that the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole similarly reduced the risk of local recurrence in women with DCIS treated with breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy (IBIS II) or was superior to tamoxifen in women <60 years of age (NSABP B35) [25, 26].

In summary, while standard therapy for DCIS has largely been de-escalated from mastectomy to breast conserving surgery with radiation (with or without endocrine therapy), the addition of radiation therapy and even endocrine therapy to breast conserving surgery is likely overtreatment for some women with DCIS.

De-escalation of treatment

Attempting to further de-escalate treatment for women with DCIS may be accomplished by (1) the identification of women with DCIS at low risk for local recurrence; (2) evaluating the potential role of active surveillance for the management of patients with low risk DCIS; and (3) “de-escalation” of the diagnosis of DCIS by pathologists.

Identification of women with DCIS at low risk for local recurrence

Identification of risk factors for local recurrence of DCIS after breast conserving therapy provides insights into which patients may have “low risk” DCIS and may, therefore, be candidates for further de-escalation of therapy. Many studies have demonstrated that a variety of clinical factors, tumor factors, and treatment factors influence the risk of local recurrence of DCIS and/or the progression to invasive breast cancer (Table 2). Based on the results of these primarily retrospective studies, the combination of features that appears to most consistently characterize DCIS with a lower risk of recurrence and/or progression to invasive breast cancer includes older age, mammographic detection, small size, non-high grade histology, and negative margins of excision.

There are three prospective studies that have attempted to determine if low risk DCIS lesions can be safely treated with breast conserving surgery without radiation therapy [27,28,29] (Table 3). Unfortunately, these prospective studies have been unable to identify a subset of patients with low risk DCIS treated with breast conserving surgery alone who have local recurrence rates of <10% after long-term follow-up based on conventional clinical and pathologic features. However, the views of what constitutes an acceptably low rate of local recurrence vary. For example, in the RTOG 9084 trial comparing breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy to breast conserving surgery alone for women with low risk DCIS [29], local recurrence rates in patients treated with breast conserving surgery alone were similar to the risk of subsequent breast cancer in women with lobular carcinoma in situ (~1%/year), a lesion that is managed conservatively (i.e., without attempt at surgical excision to negative margins and without radiation therapy).

More recent attempts to refine risk stratification among patients with DCIS have focused on the evaluation of gene expression profiling and biomarker analysis. The Oncotype DCIS score is a 12 gene RT-PCR-based assay that stratifies women with DCIS into low, intermediate, and high risk groups based on the gene expression signature. However, in two cohorts of patients (one derived from the ECOG E5194 prospective study of women with DCIS treated with breast conserving surgery alone and the other derived from the Ontario DCIS cohort) the 10-year local recurrence rates in the low risk groups were 12–13%, local recurrence rates that are too high for many clinicians to avoid recommending radiation therapy [30, 31]. A more recent meta-analysis combined data from these two cohorts and attempted to further refine the risk estimates provided by the Oncotype DCIS score using clinico-pathologic features (i.e., patient age and tumor size). In this analysis, a low risk group with a 10-year local recurrence rate of 7.2% was identified. This group was composed of women ≥50 years of age with DCIS lesions ≤1 cm who had a low risk DCIS score [32]. More recently, a signature that combines several biomarkers detected by immunohistochemistry with clinico-pathologic factors was reported to be predictive of recurrence risk and to predict benefit from radiation therapy [33]. Among patients treated with breast conserving surgery alone this assay (DCISionRT) identified a group of women with DCIS with an 8% risk of an ipsilateral breast event at 10 years in the initial population analyzed [33] and a 10% 10-year ipsilateral breast event risk in a subsequent validation study [34]. Taken together the results of these studies suggest that the combination of clinico-pathologic factors and biological features is better at identifying women with low risk DCIS than either alone.

Clinical trials of active surveillance for DCIS

In an effort to identify whether there is a subset of women with DCIS who require no treatment beyond the initial diagnostic core needle biopsy, several groups initiated randomized clinical trials to compare active surveillance to standard therapy for women with low risk DCIS. Until recently, three such trials were accruing patients: The LORIS trial in the United Kingdom, the LORD trial in continental Europe, and the Comparison of Operative vs Medical Endocrine Therapy (COMET) trial in the U.S. [6, 8, 35] (Table 4). In addition, the LORETTA trial in Japan is a prospective, single-arm trial of active surveillance and endocrine therapy for low risk DCIS [8, 36]. However, both the LORIS and LORD trials have recently been converted to registry trials due to lower than expected accrual. Therefore, the COMET trial is now the only prospective, randomized clinical trial that will be able to provide results comparing active surveillance to standard therapy for women with low risk DCIS.

The COMET trial is a prospective, randomized non-inferiority trial comparing guideline concordant care with active surveillance for women with low risk DCIS diagnosed on a breast core needle biopsy. This trial is open to women ≥40 years of age with low or intermediate grade DCIS that is ER positive and/or progesterone receptor positive. Two pathologists must agree on the diagnosis. The presence of comedo necrosis in the DCIS was initially an exclusion criterion, but was subsequently permitted when it became clear that there was poor interobserver agreement among pathologists on the definition of comedo necrosis [37]. Enrollment in the COMET trial is also open to women who have had a surgical excision for DCIS with positive margins but in whom the DCIS otherwise meets enrollment criteria, as well as to women with atypical ductal hyperplasia bordering on DCIS on a core needle biopsy. The use of endocrine therapy is optional. The accrual goal for this trial is 1200 patients; as of June 23, 2020, 537 patients have been enrolled. The primary clinical endpoint of the trial is the development of an ipsilateral invasive breast cancer within 2 years; rates of ipsilateral breast cancer at 5, 7, and 10 years will also be evaluated.

Clinical trials of active surveillance raise the question of how often patients with a core needle biopsy showing DCIS have concurrent invasive carcinoma in the breast. A meta-analysis of 52 studies containing 7350 cases of DCIS diagnosed on core needle biopsy in which a subsequent surgical excision was performed reported a pooled upgrade rate to invasive cancer of 25.9%. However, the more clinically germane question is: what is the upgrade rate for patients who would have been eligible for the clinical trials of active surveillance? A number of studies have attempted to address this question by identifying patients with DCIS who underwent surgical excision but who would have been eligible for one or more of the active surveillance trials based on trial entry criteria and then determining the frequency of invasive cancer in the surgical specimens (Table 5). While some of these studies are limited by small patient numbers, upgrade rates to invasive breast cancer range from 6 to 24% [38,39,40,41]. The clinical significance of these findings remains to be determined, but these studies demonstrate that a proportion of patients enrolled in the active surveillance trials of DCIS will have undiagnosed invasive carcinoma.

De-escalation of the diagnosis of DCIS by pathologists

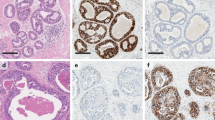

Given the trend toward de-escalation of treatment, it seems prudent for pathologists to assist in this by attempting to “de-escalate” the diagnosis of DCIS in borderline cases. While the most recent World Health Organization Classification of Breast Tumours reiterates the traditional quantitative criteria of Page and of Tavassoli and Norris for the distinction between atypical ductal hyperplasia and low grade DCIS (i.e., 2 spaces and 2 mm, respectively), it further indicates that “these thresholds are arbitrary and should be used as general guidelines. Because both of these systems were developed on the basis of findings in excisional biopsies, the criteria should be applied with caution, and the WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board recommends a conservative approach when lesions of limited extent are identified, particularly in core needle biopsies, in which the entire lesion may not be visualized” [42]. For example, Fig. 1 illustrates core needle biopsies from four different patients containing atypical, low grade, ductal pattern proliferations that range in extent from 2 spaces (Fig. 1a) to 2.5 mm (Fig. 1d). Each of these lesions had been diagnosed as DCIS, all four patients underwent mastectomy, and none had DCIS in the mastectomy specimen. If these cases had been given diagnoses that fell short of DCIS (e.g., severely atypical ductal hyperplasia, severely atypical intraductal proliferation bordering on DCIS, etc.), it is likely that none of these patients would have undergone mastectomy which, in retrospect, was overtreatment for all of these patients. Thus, cases of this type illustrate the value of using the conservative approach to atypical ductal lesions of limited extent as currently recommended by WHO [42]. They further emphasize that, given the concerns about the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS, pathologists can help mitigate the problem by taking a conservative approach for borderline lesions, especially in core needle biopsies.

Conclusions

Concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS have led to efforts to de-escalate therapy. The combination of breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy has replaced mastectomy as the most common form of treatment for DCIS, but this still likely represents overtreatment for many patients. While the reproducible identification of low risk DCIS has remained elusive, ongoing clinical trials of active surveillance of patients with presumed low risk DCIS and their correlative science components will provide important information on the feasibility of further de-escalating therapy for DCIS, provide new insights into factors associated with the progression of DCIS to invasive breast cancer, and perhaps identify new targets for prevention.

References

Burstein HJ, Polyak K, Wong JS, Lester SC, Kaelin CM. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. N. Engl J Med. 2004;350:1430–41.

Hanna WM, Parra-Herran C, Lu FI, Slodkowska E, Rakovitch E, Nofech-Mozes S. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: an update for the pathologist in the era of individualized risk assessment and tailored therapies. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:896–915.

Erbas B, Provenzano E, Armes J, Gertig D. The natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:135–44.

Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–13.

Welch HG. The heterogeneity of cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169:207–8.

van Seijen M, Lips EH, Thompson AM, Nik-Zainal S, Futreal A, Hwang ES, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: to treat or not to treat, that is the question. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:285–92.

Lazzeroni M, DeCensi A. De-escalating treatment of low-risk breast ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1252–4.

Hwang ES, Solin L. De-escalation of locoregional therapy in low-risk disease for DCIS and early-stage invasive cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2230–9.

Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Gnant M, Dubsky P, Loibl S, et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1700–12.

Smith IE, Okines AFC. De-escalating and escalating systemic therapy of early breast cancer. Breast. 2017;34:S5–S9.

Morrow M. De-escalating and escalating surgery in the management of early breast cancer. Breast. 2017;34:S1–S4.

Shah C, Vicini F. Accelerated partial breast irradiation-redefining the treatment target for women with early stage breast cancer. Breast J. 2019;25:408–17.

White J, Thompson A, Whelan T. Accelerated partial breast irradiation and intraoperative partial breast irradiation: reducing the burden of effective breast conservation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2254–62.

Punglia RS, Schnitt SJ, Weeks JC. Treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ after excision: would a prophylactic paradigm be more appropriate? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1527–33.

Welch HG, Black WC. Using autopsy series to estimate the disease “reservoir” for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: how much more breast cancer can we find? Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1023–8.

Desouki MM, Li Z, Hameed O, Fadare O, Zhao C. Incidental atypical proliferative lesions in reduction mammoplasty specimens: analysis of 2498 cases from 2 tertiary women’s health centers. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1877–81.

Eusebi V, Feudale E, Foschini MP, Micheli A, Conti A, Riva C, et al. Long-term follow-up of in situ carcinoma of the breast. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11:223–35.

Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Simpson JF, Page DL, Dupont WD. Continued observation of the natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ reaffirms proclivity for local recurrence even after more than 30 years of follow-up. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:662–9.

Rosen PP, Braun DW Jr., Kinne DE. The clinical significance of pre-invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:919–25.

Collins LC, Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, Connolly JL, Colditz GA, Schnitt SJ. Outcome of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ untreated after diagnostic biopsy: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer. 2005;103:1778–84.

Solin LJ. Management of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast: present approaches and future directions. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21:33.

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative G, Correa C, McGale P, Taylor C, Wang Y, Clarke M, et al. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:162–77.

Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Fisher ER, Mamounas E, et al. Tamoxifen in treatment of intraductal breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-24 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1993–2000.

Allred DC, Bryant J, Land S, Paik S, Fisher E, Julian T, et al. Estrogen receptor expression as a predictive marker of the effectiveness of tamoxifen in the treatment of DCIS: findings from NSABP Protocol B-24. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;76:S36.

Forbes JF, Sestak I, Howell A, Bonanni B, Bundred N, Levy C, et al. Anastrozole versus tamoxifen for the prevention of locoregional and contralateral breast cancer in postmenopausal women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ (IBIS-II DCIS): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:866–73.

Margolese RG, Cecchini RS, Julian TB, Ganz PA, Costantino JP, Vallow LA, et al. Anastrozole versus tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with ductal carcinoma in situ undergoing lumpectomy plus radiotherapy (NSABP B-35): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387:849–56.

Wong JS, Chen YH, Gadd MA, Gelman R, Lester SC, Schnitt SJ, et al. Eight-year update of a prospective study of wide excision alone for small low- or intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:343–50.

Solin LJ, Gray R, Hughes LL, Wood WC, Lowen MA, Badve SS, et al. Surgical excision without radiation for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: 12-Year results from the ECOG-ACRIN E5194 study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3938–44.

McCormick B, Winter K, Hudis C, Kuerer HM, Rakovitch E, Smith BL, et al. RTOG 9804: a prospective randomized trial for good-risk ductal carcinoma in situ comparing radiotherapy with observation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:709–15.

Solin LJ, Gray R, Baehner FL, Butler SM, Hughes LL, Yoshizawa C, et al. A multigene expression assay to predict local recurrence risk for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:701–10.

Rakovitch E, Nofech-Mozes S, Hanna W, Baehner FL, Saskin R, Butler SM, et al. A population-based validation study of the DCIS Score predicting recurrence risk in individuals treated by breast-conserving surgery alone. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152:389–98.

Rakovitch E, Gray R, Baehner FL, Sutradhar R, Crager M, Gu S, et al. Refined estimates of local recurrence risks by DCIS score adjusting for clinicopathological features: a combined analysis of ECOG-ACRIN E5194 and Ontario DCIS cohort studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169:359–69.

Bremer T, Whitworth PW, Patel R, Savala J, Barry T, Lyle S, et al. A biological signature for breast ductal carcinoma in situ to predict radiotherapy benefit and assess recurrence risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5895–901.

Weinmann S, Leo MC, Francisco M, Jenkins CL, Barry T, Leesman G, et al. Validation of a ductal carcinoma in situ biomarker profile for risk of recurrence after breast-conserving surgery with and without radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4054–63.

Grimm LJ, Shelley Hwang E. Active surveillance for DCIS: the importance of selection criteria and monitoring. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:4134–6.

Kanbayashi C, Iwata H. Current approach and future perspective for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:671–7.

Harrison BT, Hwang ES, Partridge AH, Thompson AM, Schnitt SJ. Variability in diagnostic threshold for comedo necrosis among breast pathologists: implications for patient eligibility for active surveillance trials of ductal carcinoma in situ. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:1257–62.

Pilewskie M, Stempel M, Rosenfeld H, Eaton A, Van Zee KJ, Morrow M. Do LORIS trial eligibility criteria identify a ductal carcinoma in situ patient population at low risk of upgrade to invasive carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3487–93.

Grimm LJ, Ryser MD, Partridge AH, Thompson AM, Thomas JS, Wesseling J, et al. Surgical upstaging rates for vacuum assisted biopsy proven DCIS: implications for active surveillance trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3534–40.

Jakub JW, Murphy BL, Gonzalez AB, Conners AL, Henrichsen TL, Maimone ST, et al. A validated nomogram to predict upstaging of ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2915–24.

Patel GV, Van Sant EP, Taback B, Ha R. Patient selection for ductal carcinoma in situ observation trials: are the lesions truly low risk? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:712–3.

Allison KH, Collins LC, Moriya T, Sanders ME, Visscher DW Atypical ductal hyperplasia. In: WHO Classfication of Tumours Editorial Board, editor. Breast Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2019. p. 18–21.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schnitt, S.J. Diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ in an era of de-escalation of therapy. Mod Pathol 34 (Suppl 1), 1–7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-00665-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-00665-x