Abstract

The involvement of human papillomavirus (HPV) in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma was investigated in a series of ten cases (seven laryngeal and three hypopharyngeal), retrieved from the files of three tertiary hospitals in the 2000–2017 period, through polymerase chain reaction with SPF10 primers and INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra II (Innogenetics). Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was tested in all cases with in situ hybridization INFORM EBER Probe (Ventana Medical Systems). p16 and p53 expression were immunohistochemically analyzed. Calculated annual incidence was 0.013/100,000, and prevalence was 0.2% of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. All cases were EBV negative. HPV was detected in five cases, three of which also overexpressed p16. HPV16 was detected in four cases, and HPV58 in one case. Five cases were HPV negative, only one of these five overexpressed p16. No recurrence was observed in nine cases during follow-up. The 5-year disease-specific-survival rate was 100%. Mean overall survival was 87 months. Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx are not related to EBV. Simultaneous HPV+/p16+ is consistent with HPV causation in a fraction of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma are extremely rare neoplasms, which present frequently with cervical lymph node and systemic metastases (75% and 29% of cases, respectively) [1] with a reported disease-specific survival of 63% at 5 years [2].

Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma occur more frequently in the larynx than in the hypopharynx and, within the larynx, the supraglottis is the most commonly affected site. Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinomas are more common in Caucasian populations than in Asian populations and occur at a mean age of 60 years with a male predominance [1].

The etiopathogenesis of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinomas remains controversial. Tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are likely contributing factors. However, in contrast with the much more common nasopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma, the association with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma is weaker [3]. Recently, a series of oropharyngeal carcinomas with well-developed lymphoepithelial features has been shown to be EBV-unrelated and HPV-related, similarly to oropharyngeal non-keratinizing head and neck carcinomas [4].

In the same way we looked for the presence of a similar association with HPV and EBV in the largest series of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma with lymphoepithelial features so far investigated.

Materials and methods

Cases were retrieved from the files of three tertiary hospitals in the period 2000–2017. Three pathologists (AN, MG, and JT) reviewed the cases. Taken together, the three hospitals gave coverage to a total reference population of 1,319,723 [5]. Only cases diagnosed among the reference population were used to calculate the annual incidence according to the formula: Incidence = [number of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma diagnosed in the reference population in the period investigated/(reference population number × number of years)] × 100,000. Prevalence was calculated as the ratio between the number of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma cases and the total number of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers.

Ten-micrometer-thick sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were cut using the sandwich technique, which implies that the first and last sections (4 µm thick) were stained with H&E for histological confirmation of tumor presence, whereas the central sections were used for DNA extraction. Sectioning and sample preparation were carried out with the highest measures to avoid contamination and cross-contamination. The microtome blade was replaced after each case. A vacuum cleaner was used.

The tissue sections were digested with proteinase K in a volume of 250 μL at 56 °C overnight. Proteinase K was heat inactivated at 95 °C for 10 min. A 1/10 dilution of the sample was used for PCR (10 μL).

HPV detection was performed with a polymerase chain reaction-based method and hybridization of the amplified fragment using the INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra II (Innogenetics Diagnostica, Gent, Belgium).

EBV mRNA was analyzed through in situ hybridization of EBER genes 1 and 2 with INFORM EBER probe (Ventana, Medical Systems, Tucson, USA) and the slides were counterstained with Ventana Red Counterstain (Ventana, Medical Systems, Tucson, USA). A positive hybridization was defined as punctuate or diffuse signals in the nucleus of the tumor cells. An appropriate positive control was used in all cases.

p16 expression was analyzed through immunohistochemistry with CINtec® p16 Histology (Ventana, Medical System, Tucson, USA). A diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in ≥ 50% of tumor cells was considered positive.

Expression of p53 was assessed by immunohistochemical staining using anti-p53 monoclonal mouse anti-human p53 protein, Clone DO-7 (Ventana, Medical System, Tucson, USA).

Results

Ten patients with lymphoepithelial carcinomas of larynx or hypopharynx were identified among a total number of 4952 patients with laryngeal or hypopharyngeal carcinomas. All patients were male and the mean age was 64 years. Three of the cases were patients from the population of reference of the three hospitals, four cases were received in pathology consultation, and three patients were referred for treatment from other hospitals. This results in an estimated annual incidence of 0.013/100,000, and a prevalence of 0.2% of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. The main characteristics of all patients included in the study are shown in Table 1.

Histologically, all cases showed sheets of pleomorphic cells with little or no evidence of squamous differentiation and indistinct cell borders intermingled with a dense inflammatory infiltrate composed mostly of lymphocytes or plasma cells (Fig. 1).

a–d Characteristic features of lymphoepithelial carcinoma in four of the cases included in this series. Tumor cell are undifferentiated and arrange in syncytial fashion surrounded and infiltrated by inflammatory cells. b shows abundant atypical mitotic figures. d shows a prominent plasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. Original magnification 20 ×

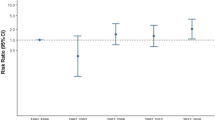

All ten cases were consistently negative for EBV. Five cases were HPV-positive: four type 16 and one type 58. Case 3 was positive for HPV type 58 only in one out of two different tumor samples (Fig. 2). p16 protein expression was detected in four laryngeal cases, three of them HPV-type 16 positive and one HPV negative (Table 1). Fifty-five percentage of cases showed positivity for p53 immunohistochemical staining in more than 50% of tumor cells. These cases were p16-negative (Table 1).

Follow-up was available in nine patients, ranging between 2 and 11 years. No patient experienced recurrence during follow-up. Three patients are alive and free of disease. In four patients the cause of death was attributed to development of another extralaryngeal malignant neoplasm (one patient each with esophageal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lung carcinoma and gastric adenocarcinoma). The two remaining patients died of other causes non-related to the laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma. The 5-year disease-specific-survival rate was 100%. Mean overall survival was 87 months.

Discussion

Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma are considered rare and aggressive neoplasms. About 40 cases have been reported, always as single cases or short series [3]. We estimated the annual incidence in 0.013/100,000, and the prevalence in 0.2%, a figure previously reported [6]. Actual prevalence should be lower (between 0.06 and 0.2%), as complex and uncommon cases tend to accumulate in tertiary specialized centers as it is the case in seven of the cases included in this series.

The etiology of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma remains controversial. Only about a third of the cases reported in the literature in which this analysis has been conducted have shown EBV positivity. This figure is significantly lower that the involvement of nasopharyngeal carcinomas, where almost all cases are EBV-related. None of our tumors was positive for EBV, suggesting that the percentage of EBV involvement in these tumors might be even lower, similarly to the results reported by MacMillan et al. [7]. So far, only six out of 19 tested cases are positive [1, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Including our cases, EBV prevalence in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma drops to about 20%.

High-risk HPV prevalence in lymphoepithelial carcinomas differs markedly between sites, with the highest figures in the oropharynx, where 86–94% of cases have been reported to be HPV-positive [4, 17]. In the nasopharynx, HPV-positive cases accumulate in patients from non-endemic areas, such as Caucasian Americans. In this group, more than 30% of nasopharyngeal carcinomas are HPV-positive, whereas among patients from areas where nasopharyngeal carcinomas are endemic HPV-associated carcinomas are exceedingly unusual. Previously reported HPV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinomas have constantly been of non-keratinizing type [18, 19]. Finally, although about 20% of sinonasal squamous carcinomas are HPV-associated, HPV has not been reported in sinonasal lymphoepithelial carcinomas [20]. The participation of HPV in laryngeal carcinoma has been largely debated, although current belief points to a low participation [21, 22].

Interestingly, half of our tumors were positive for HPV DNA, four for type 16 and one for type 58. In three of them (all HPV16) p16 protein expression was intense and diffuse, indicating that the virus was transcriptionally active and, therefore, that HPV was likely involved in the oncogenesis of the neoplasm. The three HPV16-positive and p16-positive cases were located in the larynx. This finding has not been previously reported and is the first time that HPV is linked to laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma in a similar way as in oropharyngeal carcinomas.

The fourth case lacked p16 protein expression, questioning the viral transcriptional activity. Occasionally, HPV-positive, p16-negative tumors show transcriptional activity in RNA studies, consistent with causation [23]. In these cases, absence of p16 protein expression could reflect CDKN2A silencing due to gene promoter methylation or homozygous deletion [24]. The type 58 positive case was only positive in one out of two different tumor samples, and tumor cells were p16-negative, two facts that point against a viral etiology for this particular case. Should the virus be a tumor driver, it should be found in all tumor cells (or at least in cells in all parts of the tumor) and tumor cells should be strongly and diffusely positive for p16 protein expression. A single case showed p16 protein overexpression and was negative for HPV. This is not surprising as we and others have previously described this phenomenon in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, where p16 expression can reflect different CDKN2A genetic alterations [24, 25]. A PCR false-negative result would be also an alternative explanation. Among vulvar carcinomas, HPV−/p16 + cases are similar to those unquestionably HPV-related, indicating that these cases may represent false-negative HPV DNA results [23], but we consider this hypothesis unlikely, as built-in controls for sample DNA integrity were consistently positive. In this series p16 and p53 overexpression show an inverse relationship. That is, either p16 or p53 is positive, but not both simultaneously. This reminds the model of vulvar neoplasia where carcinomas and preinvasive lesions (VIN) are either p16 protein positive, p53 protein negative reflecting a viral etiology, or p16 protein negative and p53 protein positive, indicating a TP53 mutation, non-HPV-related etiology [26]. It is tempting to speculate that the HPV type 16 positive, p16 protein and p53 protein negative could be an actual HPV-driven tumor with simultaneous CDKN2A gene deletion which is a common alteration in laryngeal carcinoma [27]. However, this situation is unlikely, because CDKN2A genetic alterations accumulate in HPV-negative tumors in the head and neck [28].

Aggressiveness of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinomas is highlighted by the high number of cases presenting with lymph metastasis at diagnosis (about 75% of cases). According to SEER data, 5-year disease-specific mortality of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma is about 60% [2] but our results show a better survival. In fact, 5-year overall survival was 63.5%, but disease-specific survival was 100%, as none of the cases included in the analysis with available follow-up died because of the lymphoepithelial carcinoma. This good prognosis was also reported by MacMillan et al. [7]. Interestingly, most of deaths in our series were due to second neoplasms. Sone et al. reported a 72-year-old patient with a laryngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma who died of renal cell carcinoma 3 months after surgery [14]. In our series, four patients who developed second neoplasms died of this new cancer at 3, 5, 7, and 8 years. This high frequency of second neoplasms observed in our series could be related to the long period in which our patients were followed up, much longer than in most of the previously reported cases.

In summary, our results, obtained from the largest series of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma published so far, confirm the low incidence and low prevalence of this particular neoplasm that could have a better prognosis than previously estimated, in spite of its tendency to present with locoregional dissemination. Here we show for the first time evidence of HPV involvement in laryngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma in a similar way to oropharyngeal cases. These results confirm that EBV positivity is not required for the diagnosis of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma and support the need for including HPV testing in the analysis of metastatic lymphoepithelial carcinoma of unknown origin.

References

Marioni G, Mariuzzi L, Gaio E, Portaleone S, Pertoldi B, Staffieri A. Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the larynx. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:429–34.

Chan JYK, Wong EWY, Ng SK, Vlantis AC. Non-nasopharyngeal head and neck lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma in the United States: a population-based study. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1294–300.

Gaulard P, Bishop J, Gillison M. Lymphoepithelial carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. Who classification of head and neck tumours, 4th edn. Lyon: International Agency for Research in Cancer; 2017, p. 90.

Singhi AD, Stelow EB, Mills SE, Westra WH. Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma of the oropharynx: a morphologic variant of HPV-related head and neck carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:800–5.

Servei Català de la Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya. Dependència—influencia territorial Regió Sanitària Barcelona. Àrees bàsiques de salut Hospitals [Internet]. http://catsalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/catsalut/catsalut_territori/barcelona/documents/arxiu/dependencia_influencia_territorial_rsb_abs-hospitals_2005.pdf

Micheau C, Luboinski B, Schwaab G, Richard J, Cachin Y. Lymphoepitheliomas of the larynx (undifferentiated carcinoma of nasopharyngeal type). Clin Otolaryngol. 1979;4:43–48.

MacMillan C, Kapadia SB, Finkelstein SD, Nalesnik MA, Barnes L. Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the larynx and hypopharynx: study of eight cases with relationship to Epstein-Barr virus and p53 gene alterations, and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1172–9.

Frank DK, Cheron F, Cho H, DiConstanzo D, Sclafani AP. Nonnasopharyngeal lymphoepitheliomas (undifferentiated carcinomas) of the upper aerodigestive tract. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:305–10.

Weiss LM, Gaffey MJ, Shibata D. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma and its relationship to the Epstein-Barr virus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:156–8.

Wu TC, Mann RB, Epstein JI, MacMahon E, Lee WA, Charache P. Abundant expression of EBER1 small nuclear RNA in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A morphologically distinctive target for detection of Epstein-Barr virus in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded carcinoma specimens. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1461–9.

Andryk J, Frejie JE, Schultz CJ, Campbell BH, Komorowski RA. Lymphoepithelioma of the larynx. Am J Otolaryngol. 1996;17:61–63.

Zbaren P, Borisch B, Lang H, Greiner R. Undifferentiated carcinoma of nasopharyngeal type of the laryngopharyngeal region. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:688–93.

Tardio JC, Cristobal E, Burgos F, Menárguez J. Absence of EBV genome in lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas of the larynx. Histopathology. 1997;30:126–8.

Sone M, Nakashima T, Nagasaka T, Itoh A, Yanagita N. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the larynx associated with an Epstein-Barr viral infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:134–7.

Dray T, Vargas H, Weidner N, Sofferman RA. Lymphoepitheliomas of the laryngohypopharynx. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:263–6.

Kermani W, Belcadhi M, Sriha B, Abdelkéfi M. Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the larynx. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2015;132:231–3.

Carpenter DH, El Mofty SK, Lewis JS Jr. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the oropharynx: a human papillomavirus-associated tumor with a favorable prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1306–12.

Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, Walline HM, Komarck C, Feng FY, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:580–8.

Lin Z, Khong B, Kwok S, Cao H, West RB, Le Q-T, et al. Human papillomavirus 16 detected in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white americans but not in endemic southern Chinese patients. Head Neck. 2014;35:709–14.

Larque AB, Hakim S, Ordi J, Nadal A, Diaz A, del Pino M, et al. High-risk papillomavirus is transcriptionally active in a subset of sinonasal squamous call carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:343–51.

Chernock RD, Wang X, Gao G, Lewis JS Jr, Zhang Q, Thorstad WL, et al. Detection and significance of human papillomavirus, CDKN2A (p16) and CDKN1A (p21) expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:223–31.

Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M, Halec G, Quiros B, Tous S, et al. HPV involvement in head and neck cancers: comprehensive assessment of biomarkers in 3680 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv403.

Rakislova N, Clavero O, Alemany L, Saco A, Quirós B, Lloveras B, et al. Histological characteristics of HPV-associated and -independent squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva: a study of 1,594 cases. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:2517–27.

Jares P, Nadal A, Fernandez PL, Pinyol M, Hernández L, Cazorla M, et al. Disregulation of p16MTS1/CDK4I protein and mRNA expression is associated with gene alterations in squamous-cell carcinoma of the larynx. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:705–11.

Larque AB, Conde L, Hakim S, Alos L, Jares P, Vilaseca I, et al. p16INK4a overexpression is associated with CDKN2A mutation and worse prognosis in HPV-negative laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:375–82.

Santos M, Montagut C, Mellado B, Garcia A, Ramon y Cajal S, Cardesa A, et al. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 and p53 in premalignant and malignant epithelial lesions of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:206–14.

Jares P, Fernandez PL, Nadal A, Cazorla M, Hernández L, Pinyol M. et al. p16MTS1/CDK4I mutations and concomitant loss of heterozygosity at 9p21-23 are frequent events in squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Oncogene. 1997;15:1445–53.

Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, Kostic AD, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–60.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Acuña, G., Gomà, M., Temprana-Salvador, J. et al. Human papillomavirus in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma. Mod Pathol 32, 621–626 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0188-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0188-2

This article is cited by

-

Challenging Tumor Heterogeneity with HER2, p16 and Somatostatin Receptor 2 Expression in a Case of EBV-Associated Lymphoepithelial Carcinoma of the Salivary Gland

Head and Neck Pathology (2023)

-

Development of head and neck pathology in Europe

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Hypopharynx, Larynx, Trachea and Parapharyngeal Space

Head and Neck Pathology (2022)

-

Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of larynx and hypopharynx: a systematic review and pooled analysis

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2022)