Abstract

The development of high-performance, portable and miniaturized gas sensors has aroused increasing interest in the fields of environmental monitoring, security, medical diagnosis, and agriculture. Among different detection tools, metal oxide semiconductor (MOS)-based chemiresistive gas sensors are the most popular choice in commercial applications and have the advantages of high stability, low cost, and high sensitivity. One of the most important ways to further enhance the sensor performance is to construct MOS-based nanoscale heterojunctions (heteronanostructural MOSs) from MOS nanomaterials. However, the sensing mechanism of heteronanostructural MOS-based sensors is different from that of single MOS-based gas sensors in that it is fairly complex. The performance of the sensors is influenced by various parameters, including the physical and chemical properties of the sensing materials (e.g., grain size, density of defects, and oxygen vacancies of materials), working temperatures, and device structures. This review introduces several concepts in the design of high-performance gas sensors by analyzing the sensing mechanism of heteronanostructural MOS-based sensors. In addition, the influence of the geometric device structure determined by the interconnection between the sensing materials and the working electrodes is discussed. To systematically investigate the sensing behavior of the sensor, the general sensing mechanism of three typical types of geometric device structures based on different heteronanostructural materials are introduced and discussed in this review. This review will provide guidelines for readers studying the sensing mechanism of gas sensors and designing high-performance gas sensors in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution is becoming a growing concern and a serious worldwide environmental problem that threatens the wellbeing of humans and organisms. Inhalation of gas pollutants can cause many health problems, such as respiratory disease, lung cancer, leukemia, and even early death1,2,3,4. It is reported that from 2012 to 2016, millions of people died from air pollution, and billions of people face poor air quality every year5. Therefore, it is important to develop portable and miniaturized gas sensors that can provide real-time feedback and high sensing performance (e.g., sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and response and recovery time). In addition to environmental monitoring, gas sensors also play a crucial role in security6,7,8, medical diagnosis9,10, aquaculture11, and other fields12.

To date, several types of portable gas sensors based on different sensing mechanisms, such as optical13,14,15,16,17,18, electrochemical19,20,21,22, and chemiresistive sensors23,24, have been made available. Among them, metal oxide semiconductor (MOS)-based chemiresistive sensors are the most popular in commercial applications due to their high stability and low cost25,26. The concentration of pollutants can be obtained by simply detecting changes in the resistance of MOSs. At the beginning of the 1960s, the first chemiresistive gas sensor based on ZnO film was reported, and it aroused great interest in the field of gas sensing27,28. To date, many different MOSs have been used as gas sensing materials, and they can be divided into two classes according to their physical properties: n-type MOSs where electrons are the majority charge carriers and p-type MOSs where holes are the majority charge carriers. Normally, p-type MOSs are less popular than n-type MOSs because the sensing response of a p-type MOS (Sp) is proportional to the square root of an n-type MOS (\(S_p = \sqrt {S_n}\)) under the same presumptions (e.g., same morphological configurations and same band bending changes in the air)29,30. However, the practical applications of single MOS-based sensors still encounter some issues, such as insufficient detection limit and poor sensitivity and selectivity. The selectivity issue can be addressed to some degree by constructing sensor arrays, known as “electronic noses”, and by combining computational analysis algorithms such as learning vector quantization (LVQ), principal component analysis (PCA), and partial least squares (PLS) analysis31,32,33,34,35. In addition, fabrication of low-dimensional MOSs32,36,37,38,39 (e.g., one-dimensional (1D), 0D and 2D nanomaterials) and modification of backbone MOSs with other nanomaterials (e.g., MOSs40,41,42, noble metal nanoparticles (NPs)43,44, carbon nanomaterials45,46, and conducting polymers47,48) to construct nanoscale heterojunctions (i.e., heteronanostructural MOSs) are the other preferred approaches to tackle the abovementioned issues. Compared with conventional thick MOS films, low-dimensional MOSs with large specific surface areas could provide more activation sites for gas adsorption and facilitate gas diffusion36,37,49. In addition, the design of MOS-based heteronanostructures can further modulate carrier transport at the heterointerface, leading to larger resistance changes due to the different working functions50,51,52. Moreover, some chemical effects (e.g., catalytic activity and synergistic surface reactions) originating from designing MOS heteronnanostructures could also improve the sensor performance50,53,54. Although the design and construction of MOS-based heteronanostructures would be a promising approach to enhance the sensor performance, current chemiresistive sensors often use a trial-and-error type approach, which is time-consuming and inefficient. Therefore, it is important to understand the sensing mechanism of MOS-based gas sensors, as it can provide a guideline for the directional design of high-performance sensors.

In recent years, MOS-based gas sensors have undergone rapid development, and some review papers about MOS nanostructures55,56,57, room-temperature gas sensors58,59, specific MOS sensing materials60,61,62, and specific gas sensors63 have been reported. Other reviews have focused on elucidating the sensing mechanism of gas sensors according to the intrinsic physical and chemical properties of the MOSs, including the role of oxygen vacancies64, the role of heteronanostructure55,65, and charge transfer at the heterointerface66. Moreover, the sensor performance is also influenced by various other parameters, including heterostructure, grain size, operation temperature, defect density, oxygen vacancy, and even the exposed crystal facet of the sensing materials25,67,68,69,70,71,72,73. However, the geometric device structure determined by the interconnection between the sensing materials and the working electrodes, which is seldom mentioned, can also significantly affect the sensing behavior of the sensor74,75,76 (more details are provided in Section 3). For example, Kumar et al.77 reported two gas sensors based on the same materials (e.g., TiO2@NiO and NiO@TiO2 bilayer-based gas sensors) and observed different resistance changes upon NH3 gases due to the different geometric structures of the devices. Therefore, it is important to consider the device structure when analyzing the gas sensing mechanism. In this review, the authors focus on the sensing mechanism based on different heteronanostructures of MOSs and the structures of the devices. We believe that this review could provide guidelines for readers who wish to understand and analyze the gas sensing mechanism, and it may facilitate the design of high-performance gas sensors in the future.

Basic sensing mechanism of a single material and enhancement sensing mechanism of a MOS heterostructure

Figure 1a illustrates the basic gas sensing mechanism model based on a single MOS. When the temperature increases, the adsorption of oxygen molecules (O2) on the surface of MOS attracts electrons from MOS and form anionic species (such as O2− and O−). Then, an electron-depletion layer (EDL) for an n-type MOS or a hole accumulation layer (HAL) for a p-type MOS is formed at the surface of the MOS15,23,78. The interaction between O2 and MOSs leads to upward bending of the MOS conduction band at the surface and forms a potential barrier. Later, when the sensor is exposed to target gases, the gases adsorbed on the surface of the MOS react with ionic oxygen species by attracting electrons (oxidizing gases) or donating electrons (reducing gases)79,80. The transfer of the electrons between the target gases and MOS can regulate the width of EDL or HAL30,81, resulting in a change in the overall resistance for the MOS-based sensors. For example, for reducing gases, the electrons will transfer from the reducing gases to the n-type MOS, leading to a decrease in EDL and a decrease in resistance, which is named n-type sensing behavior. In contrast, p-type sensing behavior is defined when a p-type MOS is exposed to the reducing gases, HAL will shrink and the resistance will increase due to the donated electrons. For oxidizing gases, the sensor response is opposite to that of reducing gases.

a Basic sensing mechanism of n- and p-type MOSs toward reducing and oxidizing gases; b Key factors and physicochemical or material properties involved in semiconductor gas sensors89

Except for the basic sensing mechanism, the gas sensing mechanisms involved in practical gas sensors are fairly complex. For instance, the practical use of gas sensors should meet many requirements (e.g., sensitivity, selectivity, and stability) depending on the users’ needs. These requirements are closely correlated with the physical and chemical properties of the sensing materials. For example, Xu et al.71 demonstrated that a SnO2-based sensor reached the highest sensitivity when the crystal diameter (d) was comparable to or less than twice the Debye length (λD) of SnO271. When d ≤ 2λD, the SnO2 is completely depleted after adsorption of O2 molecules, and the sensing response to the reducing gases is maximized. In addition, various other parameters can also influence the sensor performance, including working temperatures, crystal defects, and even the exposed crystal facets of the sensing materials25,67,68,69,70,71,72,73. Specifically, the influence of the working temperatures is ascribed to the possible competition between adsorption and desorption rates of the target gases and the surface reactivity between the adsorbed gas molecules and oxygen species4,82. The effect of crystal defects is greatly related to the content of oxygen vacancies83,84. The sensor performance can also be influenced by the exposed crystal facets due to their different reactivities67,85,86,87. The exposed crystal facets with lower density reveal more uncoordinated metal cations with higher energy that facilitate surface adsorption and reactivity88. Several main factors and relevant enhancement sensing mechanisms are listed in Table 1. Therefore, by tuning these material parameters, the sensing performance can be improved, and it is crucial for determining the key factors that influence the sensor performance.

Yamazoe89 and Shimanoe et al.68,71 performed many works to study the theoretical sensing mechanism of the sensors and proposed three independent key factors that can affect the performance of the sensors, specifically the receptor function, transducer function, and utility (Fig. 1b). Receptor function means the ability of the MOS surface to interact with gas molecules. This function is strongly related to the chemical properties of MOS and can be largely improved by introducing foreign receptors (e.g., metal NPs and other MOSs). Transducer function refers to the ability to convert reactions between the gases and MOS surface into electrical signals, and this function is dominated by the grain boundary of MOSs. Therefore, the transducer function is significantly influenced by the grain size of MOSs and the density of foreign receptors. Katoch et al.90 reported that reducing the grain size of ZnO-SnO2 nanofibrils leads to the formation of a large number of heterojunctions and improves the sensor sensitivity, which is consistent with the transducer function. Wang et al.91 compared different Zn2GeO4 grain sizes and demonstrated that the sensor sensitivity increased by 6.5 times after grain boundaries were introduced. Utility is another key factor in the performance of the sensors that describes the accessibility of interior MOSs to gases. If the gas molecules cannot access and react with the interior MOSs, the sensor responsivity is reduced. Utility is closely related to the diffusion depth of a specific gas, which is dependent on the pore size of the sensing materials. Sakai et al.92 simulated the sensing response of sensors to combustion gases with respect to different diffusion depths of gases inside the sensing films and found that both the molecular weight of the gas and the pore radius of the sensing film can affect the sensor response. Through the above discussions, it is demonstrated that high-performance gas sensors can be designed by balancing and optimizing the receptor function, transducer function and utility93.

The abovementioned works have elucidated the basic sensing mechanism of a single MOS and discussed several factors that impact the MOS performance. In addition to these factors, gas sensors based on heterostructures can further improve the sensor performance by greatly enhancing the transducer function and receptor function93. In addition, heteronanostructures can further improve the sensor performance by enhancing catalytic reactions, modulating charge transport, and providing more adsorption sites94. To date, numerous MOS heteronanostructure-based gas sensors have been studied to discuss the enhancement sensing mechanism95,96,97. Miller et al.55 summarized several of the most likely mechanisms responsible for enhancing the sensing performance of heteronanostructures, including surface-dependent, interface-dependent, and structure-dependent. Among them, the interface-dependent enhancement mechanism is too complicated to cover all interface interactions by one theory, as various heteronanostructural material-based sensors are available (e.g., n-n heterojunctions, p-n heterojunctions, p-p heterojunctions, and Schottky junctions). Generally, sensors based on heteronanostructural MOSs always involve more than two or three enhancement sensing mechanisms98,99,100. The synergistic effects of these enhancement mechanisms can amplify the reception and transduction of the sensor signal101. Therefore, understanding the sensing mechanism of sensors based on heteronanostructural materials is essential and can guide researchers in the bottom-up design of gas sensors according to their demands. In addition, the geometric device structure can also significantly affect the sensing behavior of the sensor74,75,76. To systematically analyze the sensing behavior of the sensor, the sensing mechanism of three types of device structures based on different heteronanostructural materials will be introduced and discussed in the following sections.

Three typical device structures and relevant sensing mechanisms

With the rapid development of MOS-based gas sensors, various heteronanostructural MOSs have been proposed. The charge transfer at the heterointerface depends on the different Fermi levels (Ef) of the components. At the heterointerface, the electrons move from one side with higher Ef to the other with lower Ef until their Fermi levels reach equilibrium, and vice versa for holes. Then, the carriers at the heterointerface are depleted and form a depletion layer. Once the sensor is exposed to target gases, the carrier concentration of heteronanostructural MOSs changes, as does the potential barrier height, which amplifies the detection signal. In addition, the various approaches to fabricating heteronanostructures lead to varied interconnections between the materials and electrodes, which produces different geometric device structures and leads to different sensing mechanisms. In this review, we propose three types of geometric device structures and discuss the sensing mechanism of each structure.

Definition of three types of device structures

Although the heterojunction plays a very important role in gas sensing performance, the geometric device structure of the whole sensor can also significantly affect the sensing behavior because the position of the conduction channel of the sensor greatly depends on the geometric device structure. Here, three typical types of geometric device structures based on MOS heterojunctions are discussed and shown in Fig. 2. In the first type, two MOS compounds are randomly distributed between two electrodes, and the position of the conduction channel is determined by the major MOS. In the second type, heteronanostructures are formed from different MOSs, while only one MOS is connected to the electrodes, and the conduction channel is normally located inside one MOS, which is directly connected to the electrodes. In the third type, two materials are connected to the two electrodes separately, and the device is channeled by the formed heterojunction between the two materials.

A hyphen between compounds (e.g., “SnO2-NiO”) indicates that the two constituents are simply mixed (type-I). An “@” between two compounds (e.g., “SnO2@NiO”) indicates that the backbone material (NiO) is decorated with SnO2, which is used in the type-II sensor structure. A forward slash (e.g., “NiO/SnO2”) represents the type-III sensor structure

Sensing Mechanism of the Type-I Sensor Structure

For MOS composite-based gas sensors, two kinds of MOSs are randomly distributed between the electrodes. Many fabrication methods have been developed to obtain MOS composites, including sol-gel, coprecipitation, hydrothermal, electrospinning, and mechanical mixing methods98,102,103,104. Recently, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), a class of porous crystalline framework-structured materials, which consist of a metal center and an organic linker, have been used as a template to fabricate porous MOS composites105,106,107,108. Notably, even though the composition percentages of MOS composites are the same, the sensing performance can be quite different when different fabrication processes are used109,110. For instance, Gao et al.109 prepared two sensors based on MoO3-SnO2 composites with the same atomic ratio (Mo:Sn = 1:1.9) and found that different fabrication methods led to different responsivities. Shaposhnik et al.110 reported that the response of coprecipitated SnO2-TiO2 to H2 gases differs from that of the material formed by mechanical mixing, even though the Sn/Ti ratio was the same. This difference occurred because the interconnections between the MOSs and the crystallite size of the MOSs differ with various synthesis methods109,110. When the size and shape of the grains are uniform in terms of donor density and semiconductor type, the response results should remain the same if the contact geometry is unchanged110. Staerz et al.111 reported that the sensing performance of SnO2-Cr2O3 core-shell nanofibers (CSNs) and crushed SnO2-Cr2O3 CSNs are practically identical, indicating that the nanofiber morphology shows no advantages if the characteristics of the samples remain unchanged.

In addition to different fabrication methods, the semiconducting type of two different MOSs can also influence the sensing behavior of the sensors. This can be further classified into two categories depending on whether the two MOSs are of the same type of semiconductors (n-n or p-p composite) or different types (p-n composite). When the types of MOS composite-based gas sensors are the same, the sensing response behavior remains unchanged by varying the molar ratio of the two MOSs, while the sensitivity of the sensor changes as the number of n-n or p-p heterojunctions is different102. When one component dominates in the composites (e.g., 0.9 ZnO-0.1 SnO2 or 0.1 ZnO-0.9 SnO2), the conduction channel is determined by the major MOS, which is called the homojunction conduction channel92. When the proportion of two components is comparable, the conduction channel is believed to be dominated by the heterojunction98,102. Yamazoe et al.112,113 reported that the heterocontact regions of two components could dramatically enhance the sensitivity of the sensor because the heterojunction potential barrier formed due to the different work functions of the components can efficiently tune the drift mobility of electrons when the sensor is exposed to different ambient gases112,113. Figure 3a shows that the sensors based on fibrous SnO2-ZnO hierarchical structures with different ZnO contents (0 to 10 mol% Zn) can selectively detect ethanol54. Among them, the sensor based on the SnO2-ZnO fiber (7 mol% Zn) exhibited the highest sensitivity due to the formation of a large number of heterojunctions and an increase in the specific surface area, which increased the transducer function and enhanced the sensitivity90. However, by further increasing the ZnO component to 10 mol%, the microstructure of the SnO2-ZnO composites might wrap up the surface activation sites and reduce the sensing response85. A similar tendency can be observed for sensors based on NiO-NiFe2O4 p-p heterojunction composites with different Fe/Ni ratios (Fig. 3b)114.

a SEM image of a SnO2-ZnO fiber (7 mol% Zn) and responses of the sensors to various 100 ppm gases at 260 °C;54 b responses of the sensors based on pure NiO and NiO-NiFe2O4 composites to 50 ppm different gases at 260 °C;114 (c) schematic diagram of the number of junctions in the xSnO2-(1−x)Co3O4 compositions and relevant resistance and sensing response of xSnO2-(1−x)Co3O4 compositions to 10 ppm CO, acetone, C6H6, and SO2 gases at 350 °C by varying the Sn/Co molar ratio98

For the case of p-n MOS composites, they exhibit different sensing behaviors depending on the atomic ratio of MOSs115. Generally, the sensing behavior of MOS composites greatly depends on which MOS acts as the dominating conduction channel of the sensor. Therefore, it is very important to characterize the percentage composition and the nanostructure of the composites. Kim et al.98 verified this conclusion by synthesizing a series of composite xSnO2-(1−x)Co3O4 nanofibers via an electrospinning method and studying their sensing performance. They observed that the sensing behavior of sensors based on SnO2-Co3O4 composites transits from n-type to p-type sensing behavior by reducing the SnO2 percentage (Fig. 3c)98. Moreover, compared with homojunction-dominated sensors (e.g., SnO2-rich or Co3O4-rich sensors), the heterojunction-dominated sensor (0.5 SnO2-0.5 Co3O4-based) exhibits the highest sensing response to C6H6. The intrinsic high resistance of 0.5 SnO2-0.5 Co3O4-based sensor and its higher ability to modulate the total resistance of the sensor contribute to its supreme sensitivity to C6H6. Moreover, defects originating from lattice mismatch form at the SnO2-Co3O4 heterointerfaces, which can provide preferential adsorption sites for gas molecules, lead to an enhanced sensing response109,116.

In addition to the semiconducting type of MOSs, the sensing behavior of MOS composites can also be modulated by the chemical properties of the MOS117. Huo et al.117 used a simple soak calcination method to fabricate Co3O4-SnO2 composites and observed that when the Co/Sn molar ratio was 10%, the sensor exhibited a p-type sensing response to H2, while it demonstrated an n-type sensing response to CO, H2S, and NH3 gases, as shown in Fig. 4a117. With a low Co/Sn ratio, many homojunctions form at the SnO2-SnO2 nanograin boundaries and exhibit an n-type sensing response to H2 (Fig. 4b, c)115. By increasing the Co/Sn ratio to 10 mol%, many Co3O4-SnO2 heterojunctions simultaneously form instead of the SnO2-SnO2 homojunction (Fig. 4d). Since Co3O4 is inactive to H2 while SnO2 is highly reactive to H2, the reaction between H2 and ionic oxygen species mainly occurs on the surface of SnO2117. Therefore, the electrons are transferred to SnO2 and shift the Ef of SnO2 toward the conduction band, while the Ef of Co3O4 remains unchanged. As a result, the resistance of the sensor increases, revealing that the materials with a high Co/Sn ratio exhibit p-type sensing behavior (Fig. 4e). In contrast, CO, H2S, and NH3 gases react with ionic oxygen species on both the SnO2 and Co3O4 surfaces, and electrons move from the gases to the sensor, leading to a decrease in the potential barrier height and n-type sensing behavior (Fig. 4f). This different sensing behavior is caused by the different reactivity of Co3O4 toward various gases and was further verified by Yin et al.118. Similarly, Katoch et al.119 demonstrated that SnO2-ZnO composites exhibited good selectivity for H2 with high sensitivity. This behavior occurs because H atoms can easily adsorb on O sites of ZnO via a strong hybridization between the s-orbitals of H and the p-orbitals of O, which leads to the metallization of ZnO120,121.

In summary, we can enhance the sensitivity of type-I sensors by choosing a proper fabrication method, reducing the grain size of the composites, and optimizing the molar ratio of MOS composites. In addition, a thorough understanding of the chemical properties of the sensing materials can further improve the selectivity of the sensors.

Mechanism of the Type-II Sensor Structure

The type-II sensor structure is another popular sensor structure, and various heteronanostructural materials are available, which consist of one “backbone” nanomaterial and a second or even third nanomaterial. For instance, (1D or 2D materials decorated with nanoparticles, core-shell (C-S), and multilayer heteronanostructure materials are generally used in type-II sensor structures and will be discussed in detail below.

Decorated heteronanostructures

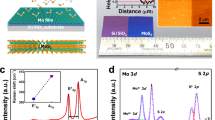

For the first kind of heteronanostructural material (decorated heteronanostructures), as demonstrated in Fig. 2b (1), the conduction channel of the sensor is connected by the backbone materials. The modified nanoparticles can provide more reaction sites for adsorption or desorption of gases due to the formation of heterojunctions and can also work as catalysts to enhance the sensing performance109,122,123,124. Yuan et al.41 observed that decorating WO3 nanowires with CeO2 nanodots can provide more adsorption sites at the CeO2@WO3 heterointerfaces and the CeO2 surface and generate more chemisorbed oxygen species to react with acetone. Gunawan et al.125. presented an ultrahigh sensitivity acetone sensor based on 1D Au@α-Fe2O3 and observed that the sensing performance of the sensor is controlled by the activation of O2 molecules as the oxygen supply. The presence of Au NPs may act as catalysts to promote the dissociation of oxygen molecules into lattice oxygen for the oxidation of acetone125. A similar result was observed by Choi et al.9, where Pt catalysts were used to dissociate adsorbed oxygen molecules into ionized oxygen species and enhance the sensing response to acetone. In 2017, the same research group demonstrated that the catalytic effect of bimetallic NPs is much higher than that of single noble nanoparticles, as shown in Fig. 5126. Figure 5a shows a schematic graph of the fabrication process for Pt-based bimetallic (PtM) NPs with an average size less than 3 nm using an apoferritin protein cage. Then, electrospinning technology was used to obtain PtM@WO3 nanofibers to improve the sensitivity and selectivity toward acetone or H2S (Fig. 5b–g). Recently, owing to maximum atom utilization efficiency and tunable electronic structures, single-atom catalysts (SACs) have exhibited superior catalytic performance in the fields of catalysis and gas sensing127,128. Shin et al.129 used Pt SA-anchored shredded melamine-derived carbon nitride nanosheets (MCN), SnCl2, and PVP as chemical sources to prepare Pt@MCN@SnO2 fiber-in-tubes for gas sensing. Although the amount of Pt@MCNs was very low (0.13 wt% to 0.68 wt%), Pt@MCN@SnO2 showed the highest sensing performance toward formaldehyde gas over other reference samples (pristine SnO2, MCN@SnO2, and Pt NPs@SnO2). This superior sensing performance can be explained by the maximized catalyst atom efficiency of Pt SAs and the minimum coverage of the active sites on SnO2129.

a Apoferritin-encapsulating method for preparing PtM-apo NPs (PtPd, PtRh, PtNi); b–d dynamic gas-sensing properties of pristine WO3, PtPd@WO3, PtRn@WO3, and Pt-NiO@WO3 nanofibers; e–g selectivity property of sensors based on PtPd@WO3, PtRn@WO3, and Pt-NiO@WO3 nanofibers toward 1 ppm interfering gases126

In addition, the formed heterojunctions between the backbone material and the nanoparticles can also efficiently modulate the conduction channel via a radial modulation mechanism to enhance the sensor performance130,131,132. Figure 6a demonstrates the sensing performance of pure SnO2 and Cr2O3@SnO2 nanowires to reducing and oxidizing gases and their corresponding sensing mechanisms131. Compared with pure SnO2 nanowires, the response of the Cr2O3@SnO2 nanowires to the reducing gases is greatly enhanced, whereas it deteriorates to oxidizing gases. These phenomena are closely related to the local suppression of the conduction channel of SnO2 nanowires in the radial direction of the formed p-n heterojunction131. The resistance of the sensor is simply tuned by changing the width of the EDL on the surface of the pure SnO2 nanowires after exposure to the reducing and oxidizing gases131. However, for Cr2O3@SnO2 nanowires, the initial EDL of the SnO2 nanowires in the air is expanded, and the conduction channel is suppressed compared with that of the pure SnO2 nanowires due to the formed heterojunctions. Therefore, when the sensor is exposed to reducing gases, captured electrons are released to the SnO2 nanowires, and the EDL dramatically shrinks, resulting in a higher sensitivity than that of the pure SnO2 nanowires. In contrast, when switching to oxidizing gases, the expansion of the EDL is limited, which leads to low sensitivity. Similar sensing response results were observed by Choi et al.133, where the sensing response of SnO2 nanowires decorated with p-type WO3 nanoparticles for reducing gases was significantly improved, while an enhanced sensitivity to oxidizing gases was observed for a SnO2 sensor decorated with n-type TiO2 nanoparticles (Fig. 6b)133. This result was mainly due to the different working functions between the SnO2 and MOS nanoparticles (TiO2 or WO3). In p-type (n-type) nanoparticles, the conduction channel of the backbone material (SnO2) expands (or shrinks) radially, and then further expansion (or shortening) of the SnO2 conduction channel is marginal upon exposure to reducing (or oxidizing) gases (Fig. 6b).

Radial modulation mechanism caused by decorated MOS NPs. a Summary of gas response to 10 ppm of reducing gases and oxidizing gases based on pure SnO2 and Cr2O3@SnO2 nanowires and relevant schematic of sensing mechanisms;131 b summary of the gas response to 1 ppm reducing gases and oxidizing gases based on pure SnO2, TiO2@SnO2 and WO3@SnO2 nanorods and relevant schematic of sensing mechanisms133

Bilayer and multilayer heteronanostructures

In bilayer and multilayer heteronanostructure devices, the conduction channel of the device is dominated by the layer that is directly in contact with the electrodes (generally the bottom layer), and the heterojunctions formed at the contact regions of the two layers can modulate the conductance of the bottom layer. Therefore, once the gases interact with the top layer, they significantly influence the conduction channel of the bottom layer and the resistance of the device134. For instance, Kumar et al.77 reported the opposite sensing behavior of TiO2@NiO and NiO@TiO2 bilayer films toward NH3. This discrepancy occurs because the conduction channels of the two sensors are dominant in different material layers (NiO and TiO2, respectively), and then the changes in the conduction channel in the bottom layer are different77.

Bilayer or multilayer heteronanostructures are commonly obtained by sputtering, atomic layer deposition (ALD), and spin coating56,70,134,135,136. The thicknesses of the films and the contact areas of the two materials can be well controlled. Figure 7a and b show the NiO@SnO2 and Ga2O3@WO3 nanofilms prepared by the sputtering method for ethanol sensing135,137. However, these methods usually result in planar films, and the sensitivity of these planar films is lower than that of 3D nanostructured materials due to their low specific surface area and low gas permeation rate. Thus, liquid phase strategies have also been proposed to fabricate bilayer films with different hierarchical structures to increase the sensing performance by increasing the specific surface area41,52,138. Zhu et al.139 combined sputtering and hydrothermal methods and obtained highly ordered ZnO nanowires on top of SnO2 nanobowls (ZnO@SnO2 nanowires) for H2S sensing (Fig. 7c). Its responsivity to 1 ppm H2S is 1.6-fold higher than that of sensors based on the ZnO@SnO2 nanofilm, which is prepared by sputtering. Liu et al.52 reported a high-performance H2S sensor by fabricating SnO2@NiO hierarchical nanostructures with an in-situ two-step chemical bath deposition method followed by thermal annealing treatment (Fig. 10d). Compared with conventional SnO2@NiO bilayer films, which are prepared by the sputtering method, the sensing performance of the hierarchical SnO2@NiO bilayer structure is dramatically enhanced owing to the increase in the specific surface area52,137.

Core-shell heteronanostructures

In core-shell heteronanostructure (CSHN)-based type-II devices, the sensing mechanism is more complex since the conduction channel is not confined to the inner shell. The fabrication routes and the thicknesses of the shell (hs) can both determine the location of the conduction channel. For example, the conduction channel is normally confined to the inner core when using bottom-up synthesis approaches, and the structure is similar to bilayer or multilayer device structures (Fig. 2b(3))123,140,141,142,143. Xu et al.144 reported a bottom-up approach to prepare NiO@α-Fe2O3 and CuO@α-Fe2O3 CSHNs by depositing a layer of NiO or CuO NPs on top of α-Fe2O3 nanorods, in which the conduction channel is confined to the core part (α-Fe2O3 nanorods). Liu et al.142 also successfully confined the conduction channel to the core part of TiO2@Si CSHNs by drop-casting TiO2 onto the as-prepared Si nanowire array. Therefore, its sensing behavior (p-type or n-type) only depends on the semiconducting type of Si nanowires.

However, most reported CSHN-based sensors (Fig. 2b(4)) are prepared by transferring synthesized CS material powders onto a chip. In this case, the conduction channel of the sensor is influenced by the thickness of the shell (hs). Kim’s group studied the effects of hs on the gas sensing performance and proposed a possible sensing mechanism100,112,145,146,147,148. It is believed that two factors contribute to the sensing mechanism of this structure: (1) the radial modulation of the EDL of the shell and (2) the electric field smearing effect (Fig. 8) 145. The researchers mentioned that the conduction channel of the carriers is mostly confined to the shell layer when hs > λD of the shell layer145. As a result, the resistance modulation of sensors based on CSHNs is mainly dominated by the radial modulation of the EDL of the shell (Fig. 8a). However, when hs ≤ λD of the shell layer, the shell layer becomes fully electron depleted by the adsorbed oxygen species and the formed heterojunction at the CS heterointerface. Therefore, the conduction channel is not only located inside the shell layer but also partially in the core part, especially when hs < λD of the shell layer. In this case, both the fully electron-depleted shell layer and the partially depleted core layer contribute to modulating the resistance of the whole CSHNs, generating an electric-field smearing effect (Fig. 8b). Some other studies use the concept of EDL volume fraction instead of electric field smearing effect to analyze the effect of hs100,148. By taking both contributions into consideration, the overall resistance modulation of the CSHNs reaches the highest when hs is comparable with λD of the shell layer, as shown in Fig. 8c. Therefore, the optimal hs of the CSHN may be close to λD of the shell layer, which is consistent with experimental observations99,144,145,146,149. Several studies have demonstrated that hs can also influence the sensing behavior of sensors based on p-n heterojunction CSHNs40,148. Lee et al.148 and Bai et al.40 systematically studied the influence of hs on the performance of p-n heterojunction CSHN (e.g., TiO2@CuO and ZnO@NiO)-based sensors by varying the ALD cycles of the shell layer. As a result, the sensing behavior transits from p-type to n-type with increasing hs40,148. This behavior occurs because at the beginning (with a limited ALD cycle number), the heterostructure can be regarded as decorated heteronanostructures. Thus, the conduction channel is confined to the core layer (p-type MOS), and the sensor shows p-type sensing behavior40. By increasing the ALD cycle number, the shell layer (n-type MOS) becomes quasi-continuous and serves as the conduction channel, resulting in n-type sensing behavior40. Similar sensing transition behaviors have also been reported on branched p-n heteronanostructures150,151. Zhou et al.150 studied the sensing behavior of Zn2SnO4@Mn3O4 branched heteronanostructures by tuning the content of Zn2SnO4 on the surface of Mn3O4 nanowires. The p-type sensing behavior is observed when Zn2SnO4 seeds form on the surface of Mn3O4. With a further increase in the content of Zn2SnO4, the sensor based on Zn2SnO4@Mn3O4 branched heteronanostructures switches to n-type sensing behavior.

Conceptual description showing the dual functional sensing mechanism of CS nanowires. a Resistance modulation by radial modulation of the electron-depleted shell layer, b adverse effect of smearing on resistance modulation, and c total resistance modulation of CS nanowires by a combination of both effects40

In summary, the type-II sensor involves many different hierarchical nanostructures, and the sensor performance depends largely on the position of the conduction channel. Therefore, it is crucial to control the location of the conduction channel of the sensor and use a suitable model based on heteronanostructural MOSs to study the enhanced sensing mechanism of the type-II sensor.

Sensing mechanism of the type-III sensor structure

The type-III sensor structure is not very common, and the conduction channel is based on the formed heterojunction between the two semiconductors, which are separately connected to the two electrodes. The unique device structure is usually obtained via microfabrication techniques, and the sensing mechanism is quite different from those of the previous two types of sensor structures. The I–V curves of the type-III sensor usually present the typical rectification characteristics due to the formed heterojunctions48,152,153. The I–V curves of the ideal heterojunction could be described by the thermionic emission mechanism of electrons over the heterojunction barrier height152,154,155.

where Va is the bias voltage, A is the device area, k is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, q is the electrical charge of the carrier, and Jn and Jp represent the hole and electron diffusion current densities, respectively. IS represents the reverse saturation current given by the following equation:152,154,155

where A*is the Richadson constant and \(V_{bi}^0\) is the built-in potential.

Therefore, the total current of the p-n heterojunction is determined by both the changes in the carrier concentrations and the heterojunction barrier height, as illustrated by Eqs. (3) and (4) 156

where nn0 and pp0 are the electron (hole) concentrations in n-type (p-type) MOSs, \(V_{bi}^0\) is the built-in potential, Dp (Dn) is the diffusion coefficient for the electron (hole), Ln (Lp) is the diffusion length for the electron (hole), and ΔEv (ΔEc) is the energy shift of the valence band (conduction band) at the heterointerface. Although the current density is proportional to the carrier density, it is inversely exponentially correlated with \(V_{bi}^0\). Therefore, the overall change in the current density is significantly dependent on the modulation of the heterojunction barrier height.

As discussed above, the construction of heteronanostructural MOS (e.g., type-I and type-II devices) can dramatically enhance the sensor performance over that of the individual components. Whereas, for the type-III device, the response of hetero-nanostructure can be either higher than both the components48,153 or just higher than only one component76 depending on the chemical properties of the materials. Several reports have illustrated that when one of the components is insensitive to target gases, the response of the heteronanostucture is much higher than that of individual components48,75,76,153. In this case, the target gas would just interact with the sensitive layer and cause the shift of Ef for the sensitive layer as well as the change of heterojunction barrier height147. Then, the total current of the device dramatically changes as it is inverse exponentially correlated with the heterojunction barrier height according to Eqs. (3) and (4) 48,76,153. However, when both n-type and p-type components are sensitive to target gases, the sensing performance may lie in between. Jose et al.76 used the sputtering method to obtain a NiO/SnO2 porous thin film-based NO2 sensor and found that the sensitivity of the sensor was only higher than that of a NiO-based sensor but lower than that of a SnO2-based sensor. This phenomenon is because SnO2 and NiO exhibit opposite responses to NO276. In addition, as the two components show different sensitivities to gases, they may cause the same trend in sensing oxidizing and reducing gases. For instance, Kwon et al.157 proposed a NiO/SnO2 p-n heterojunction-based gas sensor via an oblique-angle deposition method, as shown in Fig. 9a. Interestingly, the sensor based on the NiO/SnO2 p-n heterojunction showed the same sensing trend to H2 and NO2 (Fig. 9a). To address this result, Kwon et al.157 systematically studied how NO2 and H2 would change the carrier concentration and modulate the \(V_{bi}^0\) of both materials via I-V characterization and computational simulation (Fig. 9 b–d). Figure 9b, c demonstrate the ability of H2 and NO2 to change the carrier density of the sensor based on p-NiO (pp0) and n-SnO2 (nn0), respectively. They show that the pp0 of p-type NiO changed slightly in the NO2 environment, while a dramatic change occurred in the H2 environment (Fig. 9b). However, nn0 showed the opposite behavior for n-type SnO2 (Fig. 9c). Based on these results, the authors concluded that when the sensor based on the NiO/SnO2 p-n heterojunction was exposed to H2, the increase in nn0 led to an increase in Jn, and the slight increase in \(V_{bi}^0\) led to a low response (Fig. 9d). After exposure to NO2, the large decrease in nn0 in SnO2 and the small increase in pp0 in NiO both led to a large decrease in \(V_{bi}^0\), which ensured an enhancement of the sensing response (Fig. 9d)157. In summary, both changes in the carrier concentrations and \(V_{bi}^0\) can lead to the variation of the total current, which further influences the sensing capability.

Sensing mechanism of the gas sensor based on the type-III device structure. a Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the device based on p-NiO/n-SnO2 nanohelices and the sensing properties of the p-NiO/n-SnO2 nanohelix heterojunction sensor at 200 °C toward H2 and NO2; b, c cross-sectional SEM of the devices and simulation results of the devices having b the p-NiO layer and c the n-SnO2 layer. Measured and fitted I–V characteristics in dry air and after H2 and NO2 exposure of the b p-NiO sensor and c n-SnO2 sensor. Two-dimensional b hole density map in p-NiO and c electron map in an n-SnO2 layer with color scale simulated by using Sentaurus TCAD software. d Results of the simulation showing a three-dimensional map of the p-NiO/n-SnO2 in dry air, H2 and ambient NO2157

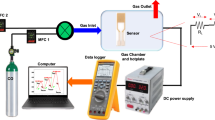

In addition to the chemical properties of the materials themselves, the Type-III device structure shows the ability to construct a self-powered gas sensor, which cannot be achieved by type-I and type-II devices. The p-n heterojunction diode structure is commonly utilized to construct photovoltaic devices owing to the inherent electric field (BEF) and shows the potential to fabricate photovoltaic room temperature self-powered gas sensors under light illumination74,158,159,160,161. The BEF at the heterointerface, which results from the difference in Fermi levels of the materials, can also contribute to the separation of electron-hole pairs. The merit of the photovoltaic self-powered gas sensor lies in its low energy consumption, as it can absorb energy from illuminated light and then drive itself or other miniaturized devices without external energy sources. For instance, Tanuma and Sugiyama162 fabricated a NiO/ZnO p-n heterojunction as a solar cell to activate a polycrystalline SnO2-based CO2 sensor. Gad et al.74 reported a photovoltaic self-powered gas sensor based on a Si/ZnO@CdS p-n heterojunction, as demonstrated in Fig. 10a. Vertically aligned ZnO nanowires were directly grown on the p-type Si substrate to form a Si/ZnO p-n heterojunction. Then, CdS nanoparticles were decorated on the surface of ZnO nanowires via chemical surface modification. Figure 10a demonstrates the sensing response results of Si/ZnO@CdS to O2 and ethanol under self-powered mode. Under light illumination, the open-circuit voltage (Voc), which was induced by the separation of electron-hole pairs under the BEF at the heterointerface of Si/ZnO, increased linearly with the number of connected diodes74,161. Voc can be expressed by Eq. (5) 156,

where ND, NA, and Ni are the concentrations of the donor, acceptor, and intrinsic carrier, respectively, and k, T, and q represent the same parameters as in previous equations. When exposure to oxidizing gases, they withdraw electrons from the ZnO nanowires and result in a decrease in \(N_D^{ZnO}\) and then Voc. In contrast, the reducing gases lead to an increase in Voc (Fig. 10a). By decorating ZnO with CdS nanoparticles, the photoexcited electrons in the CdS nanoparticles are injected into the conduction band of ZnO and interact with adsorbed gases, resulting in improved sensing performance74,160. Hoffmann et al.160,161 reported a similar photovoltaic self-powered gas sensor based on Si/ZnO (Fig. 10b). The sensor can selectively detect NO2 by modulating the working function of target gases by functionalizing ZnO nanowires with amine ([3-(2-aminoethylamino) propyl] trimethoxysilane) (amine functionalized-SAM) and thiol ((3-mercapto-propyl)-trimethoxysilane) (thiol functionalized-SAM)) (Fig. 10b)74,161.

Photovoltaic self-powered gas sensor based on a type-III device structure. a Self-powered photovoltaic gas sensors based on Si/ZnO@CdS and the self-powered sensing mechanism and sensing responses of the sensor toward oxidizing (O2) and reducing (1000 ppm ethanol) gases under solar illumination;74 b Self-powered photovoltaic gas sensors based on Si/ZnO and the sensing response to different gases after modifying ZnO with amine- and thiol-terminated SAM functionalizations161

Therefore, when discussing the sensing mechanism of type-III sensors, it is very important to determine the changes in the heterojunction barrier height and the ability of gases to affect carrier concentrations. In addition, light illumination can produce photogenerated carriers that react with gases, and these carriers are promising for self-powered gas detection.

Conclusions, future outlook, remaining challenges

As discussed in this literature review, many different MOS heteronanostructures have been fabricated to enhance the performance of sensors. Various keywords (metal oxide composites, core-shell metal oxide, hierarchical metal oxide, and self-powered gas sensor) were searched on the Web of Science database, and the differentiating features (popularity, sensitivity/selectivity, power generation potential, fabrication method, and conduction channel) of the three types of devices are summarized in Table 2. A general concept of how to design high-performance gas sensors has been discussed by analyzing the three key factors proposed by Yamazoe. Researchers have further discussed and classified the enhancement sensing mechanisms of sensors based on MOS heteronanostructures. To understand the influencing factors of gas sensors, various parameters of MOSs (e.g., grain size, operation temperatures, density of defects and oxygen vacancies, exposed crystal facet) have been investigated thoroughly. However, the influence of the geometric device structure, which is also critical to the sensing behavior of the sensors, has been ignored and has seldom been discussed. In this review, the basic sensing mechanisms of three typical types of device structures are discussed.

The grain size structure, fabrication method, and number of heterojunctions formed by the sensing materials in type-I sensors can greatly influence the sensitivity of the sensors. In addition, the sensing behavior is also influenced by the molar ratio of the components. The type-II device structure (decorated heteronanostructures, bilayer or multilayer films, and CSHNs) is the most popular device structure; it consists of two or more components, and only one of them connects to the electrodes. For this device structure, it is critical to determine the location of the conduction channel and its relative changes when studying the sensing mechanism. As type-II devices involve many different hierarchical heteronanostructures, many different sensing mechanisms have been proposed. In the type-III sensor structure, the conduction channel is dominated by the formed heterojunction at the heterointerface, and the sensing mechanism is quite different. Therefore, it is very important to determine the changes in the heterojunction barrier height of the type-III sensors once exposed to target gases. With this structure, it is possible to fabricate photovoltaic self-powered gas sensors to reduce power consumption. However, there is much progress to be made in studies of self-powered gas sensors since their current fabrication process is rather complicated and the sensitivity is much lower than that of traditional MOS-based chemiresistive gas sensors.

The key advantages of MOS gas sensors with hierarchical heteronanostructures are their fast responses and improved sensitivity. However, several key challenges (e.g., high working temperature, long-term stability, poor selectivity and reproducibility, humidity impact, and so on) of MOS gas sensors remain and need to be addressed before they can be used in practical applications. Current MOS gas sensors usually work under high temperatures, which causes high power consumption and impacts the long-term stability of sensors. There are two common approaches to address this problem: (1) the design of low power consumption sensor chips and (2) the development of novel sensing materials that can work at low temperatures or even at room temperature. One method of designing low power consumption sensor chips, one of the method is to minimize the sensor size by fabricating ceramic-based and silicon-based microhotplates163. The power consumption of ceramic-based microhotplates is approximately 50–70 mV per sensor, while the power consumption of optimized silicon-based microhotplates can decrease to 2 mW per sensor when operated continuously at 300 °C163,164. The development of novel sensing materials is an effective way to reduce the power consumption by decreasing the working temperature and can also improve the stability of the sensor. The thermal stability of MOSs becomes more challenging when the size of MOSs continues to reduce to improve the sensor sensitivity, which results in the signal drift of the sensor165. In addition, high temperature promotes the diffusion of materials across the heterointerfaces and form mixed phases, which affects the electronic properties of sensors166. Researchers have reported that the optimized operation temperatures of sensors can be reduced by choosing appropriate sensing materials and designing MOS heteronanostructures167,168. Seeking a low-temperature method of fabricating highly crystalline MOS heteronanostructures is another promising approach to enhancing stability168.

The selectivity of MOS-based sensors is another practical issue because various gases coexist with the target gas, and MOS-based sensors are normally sensitive to more than one gas and usually show cross-sensitivities. Therefore, it is crucial to improve the selectivity of the sensor to a target gas among other gases for real-world applications. Over the past few decades, the selectivity has been partially addressed by constructing gas sensor arrays known as “electronic noses (E-noses)”, and combining computational analysis algorithms such as learning vector quantization (LVQ), principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares (PLS), and so on31,32,33,34. Two main factors (the number of sensors, which is greatly related to the kinds of sensing materials, and the computational analysis) are essential for enhancing the ability of the E-nose to distinguish gases169. However, it usually requires many complex fabrication processes to increase the sensor number; thus, it is crucial to seek a facile method to enhance the E-nose performance. In addition, modification of the MOS with other materials can also enhance the selectivity of the sensor. For example, one can realize the selective detection of H2 using Pd NP-decorated MOSs due to their good catalytic activity170. In recent years, some researchers have covered the surface of MOSs with MOFs to improve the sensor selectivity through the size-excusive effect171,172. Inspired by this work, the functionalization of materials may address the issue of selectivity in some way. However, much work still needs to be performed on how to choose appropriate materials.

Reproducibility in performance among sensors fabricated under identical conditions and methods is another important requirement of large-scale fabrication and practical applications. Generally, spin- and dip-coating methods are low-cost routes to fabricate gas sensors with high throughput. However, during these processes, the sensing materials tend to aggregate, and the interconnections between the sensing materials and the substrates are weak68,138,168. Therefore, the sensitivity and stability of the sensors are significantly influenced, and the performance reproducibility is poor. Other fabrication methods, such as sputtering, ALD, pulsed laser deposition (PLD) and physical vapor deposition (PVD), can directly yield bilayer or multilayer MOS films on patterned silicon or alumina substrates. These techniques can avoid aggregation of the sensing materials and ensure the reproducibility of the sensors and demonstrate the feasibility for large-scale fabrication of planar film-based sensors173. However, the sensitivity of these planar films is usually much lower than that of 3D nanostructured materials due to their low specific surface area and low gas permeation rate41,174. New strategies for growing MOS heteronanostructures at specific locations on patterned microchips and precisely controlling the size, thickness and morphology of the sensing materials are essential for the low-cost wafer-scale fabrication of sensors with high reproducibility and sensitivity. For instance, Liu et al.174 proposed a combined “top-down” and “bottom-up” strategy to manufacture wafer-scale miniaturized gas sensors with high throughput by in-situ growth of Ni(OH)2 nanowalls at specific locations of the microhotplate wafer.

In addition, it is important to consider the impact of humidity on the sensor in real-world applications. The water molecules can compete with oxygen molecules for the adsorption site of the sensing materials and influence the responsibility of the sensors to target gases175. Similar to oxygen gases, water acts as a molecule via physical adsorption and can also present as hydroxyl radicals or hydroxyl groups in multiple oxidation stations via chemical adsorption176. Furthermore, the reliable response of sensors to target gases is a great challenge due to the high level and nonconstant humidity in the environment. Several strategies have been developed to address this issue, such as the gas preconcentration method177, humidity compensation and cross-reactive array method178 and dehumidification techniques179,180. However, these methods are costly and complex and lower the sensor’s sensitivity. Some low-cost strategies have been proposed to suppress the impact of humidity. For example, decorating SnO2 with Pd NPs can facilitate the transition of adsorbed oxygen into anionic species, and functionalization of SnO2 with materials (e.g., NiO and CuO) with a high affinity to water molecules are two possible methods to prevent the humidity dependence of the sensors181,182,183. In addition, the construction of hydrophobic surfaces by introducing hydrophobic materials can also reduce the influence of humidity36,138,184,185. However, the design of humidity-resistant gas sensors remains in its early stage, and more advanced strategies are needed to tackle these problems.

In conclusion, improvements in sensing performance (e.g., sensitivity, selectivity, low optimal working temperature) have been achieved by the construction of MOS heteronanostructures, and different enhancement sensing mechanisms have been proposed. The geometric device structure must also be taken into consideration when studying the sensing mechanism of a specific sensor. To further improve the performance of gas sensors and address the remaining challenges, exploring novel sensing materials and investigating advanced fabrication strategies are needed in the future. To tune the sensing performance in a controlled way, it is essential to systematically construct relationships between the synthesis methods and the functions of the heteronanostructure for the sensing materials. In addition, the study of the surface reactions and the changes at the heterointerfaces by state-of-the-art characterization techniques can help elucidate their sensing mechanisms and provide guidelines for the design of heteronanostructure material-based sensors. Finally, exploring modern fabrication strategies of sensors may enable the implementation of wafer-scale fabrication of miniaturized gas sensors, which lead to their industrial applications.

References

Hansel, N. N. et al. A longitudinal study of indoor nitrogen dioxide levels and respiratory symptoms in inner-city children with asthma. Environ. Health Perspect. 116, 1428–1432 (2008).

Wellenius, G. A., Bateson, T. F., Mittleman, M. A. & Schwartz, J. Particulate air pollution and the rate of hospitalization for congestive heart failure among medicare beneficiaries in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Am. J. Epidemiol. 161, 1030–1036 (2005).

Elliott, E. G. et al. Unconventional oil and gas development and risk of childhood leukemia: Assessing the evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 576, 138–147 (2017).

Yu, T. et al. Highly sensitive H2S detection sensors at low temperature based on hierarchically structured NiO porous nanowall arrays. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 11991–11999 (2015).

Institute, H. E. Start of Global air 2018, Special Report. (Boston, MA: Health Effects Institue, 2018).

Peveler, W. J. et al. Multichannel Detection and Differentiation of Explosives with a Quantum Dot Array. ACS Nano 10, 1139–1146 (2016).

Freund, P., Senkovska, I. & Kaskel, S. Switchable conductive MOF-nanocarbon composite coatings as threshold sensing architectures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 43782–43789 (2017).

Qu, J. et al. Transition-metal-doped p-type ZnO nanoparticle-based sensory array for instant discrimination of explosive vapors. Small 12, 1369–1377 (2016).

Choi, S. J. et al. Selective diagnosis of diabetes using Pt-functionalized WO3 hemitube networks as a sensing layer of acetone in exhaled breath. Anal. Chem. 85, 1792–1796 (2013).

Nasiri, N. & Clarke, C. Nanostructured gas sensors for medical and health applications: low to high dimensional materials. Biosensors 9, 43 (2019).

Srinivasan, P. & Rayappan, J. B. B. Investigations on room temperature dual sensitization of ZnO nanostructures towards fish quality biomarkers. Sens. Actuators, B 304, 127082 (2020).

Srivastava, A. K., Dev, A. & Karmakar, S. Nanosensors and nanobiosensors in food and agriculture. Environ. Chem. Lett. 16, 161–182 (2017).

Masrie, M., Adnan, R., Ahmad, A. A hybrid gas sensor based on infrared absorption for indoor air quality monitoring. Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2, (2012).

Werle, P. et al. Near-and mid-infrared laser-optical sensors for gas analysis. Opt. lasers Eng. 37, 101–114 (2002).

Dey, A. Semiconductor metal oxide gas sensors: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 229, 206–217 (2018).

Narayanan, S., Rice, G. & Agah, M. A micro-discharge photoionization detector for micro-gas chromatography. Microchim. Acta 181, 493–499 (2013).

Zimmer, C. M., Kallis, K. T. & Giebel, F. J. Micro-structured electron accelerator for the mobile gas ionization sensor technology. J. Sens. Sens. Syst. 4, 151–157 (2015).

Liu, J., Tan, Q., Xue, C. & Xiong, J. Design of a gas sensor for hydrazines based on photo-ionization principle. Appl. Mech. Mater. 44, 2050–2054 (2011).

SebtAhmadi, S. S. et al. General modeling and experimental observation of size dependence surface activity on the example of Pt nano-particles in electrochemical CO gas sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 285, 310–316 (2019).

Gębicki, J., Kloskowski, A. & Chrzanowski, W. Prototype of electrochemical sensor for measurements of volatile organic compounds in gases. Sens. Actuators, B 177, 1173–1179 (2013).

Dosi, M. et al. Ultrasensitive electrochemical methane sensors based on solid polymer electrolyte infused laser-induced graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 6166–6173 (2019).

Struzik, M., Garbayo, I., Pfenninger, R. & Rupp, J. L. M. A simple and fast electrochemical CO2 sensor based on Li7La3Zr2O12 for environmental monitoring. Adv. Mater. 30, e1804098 (2018).

Yang, M. et al. Preparation of highly crystalline NiO meshed nanowalls via ammonia volatilization liquid deposition for H2S detection. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 540, 39–50 (2019).

Bao, F. et al. Photochemical Aging of Beijing Urban PM2.5: HONO Production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 6309–6316 (2018).

Korotcenkov, G. Metal oxides for solid-state gas sensors: What determines our choice? Mater. Sci. Eng., B 139, 1–23 (2007).

Neri, G., Donato, N. Resistive gas sensors. Wiley encyclopedia of electrical and electronics engineering, 1–12, (1999).

Seiyama, T., Kato, A., Fujiishi, K. & Nagatani, M. A new detector for gaseous components using semiconductive thin films. Anal. Chem. 34, 1502–1503 (1962).

Neri, G. First Fifty Years of Chemoresistive Gas Sensors. Chemosensors 3, 1–20 (2015).

Hübner, M. et al. Influence of humidity on CO sensing with p-type CuO thick film gas sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 153, 347–353 (2011).

Kim, H. J. & Lee, J. H. Highly sensitive and selective gas sensors using p-type oxide semiconductors: Overview. Sens. Actuators, B 192, 607–627 (2014).

Song, Z. et al. Wireless self-powered high-performance integrated nanostructured-gas-sensor network for future smart homes. ACS Nano 15, 7659–7667 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Ultra-low-power smart electronic nose system based on three-dimensional tin oxide nanotube arrays. ACS Nano 12, 6079–6088 (2018).

Pour, M. N., Nikfarjam, A., Taheri, A. & Sadredini, A. R. Gas sensor array assisted with UV illumination for discriminating several analytes at room temperature. Micro Nano Lett. 14, 1064–1068 (2019).

Hu, W. et al. Electronic noses: from advanced materials to sensors aided with data processing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800488 (2019).

Zhang, B. & Gao, P. Metal oxide nanoarrays for chemical sensing: a review of fabrication methods, sensing modes, and their inter-correlations. Front. Mater. 6, 55 (2019).

Bulemo, P. M., Cho, H. J., Kim, N. H. & Kim, I. D. Mesoporous SnO2 nanotubes via electrospinning-etching route: highly sensitive and selective detection of H2S molecule. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 26304–26313 (2017).

Song, Z. et al. Nanosheet-assembled, hollowed-out hierarchical γ-Fe2O3 microrods for high-performance gas sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 3754–3762 (2020).

Meng, F. et al. UV-activated room temperature single-sheet ZnO gas sensor. Micro Nano Lett. 12, 813–817 (2017).

Kim, J. W. et al. Micropatternable double-faced ZnO nanoflowers for flexible gas sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 32876–32886 (2017).

Bai, J. et al. Debye-length controlled gas sensing performances in NiO@ZnO p-n junctional core–shell nanotubes. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 52, 285103 (2019).

Yuan, K. et al. Fabrication of a micro-electromechanical system-based acetone gas sensor using CeO2 nanodot-decorated WO3 nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 14095–14104 (2020).

Shao, S. et al. ZnO nanosheets modified with graphene quantum dots and SnO2 quantum nanoparticles for room-temperature H2S sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 5220–5230 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Nanoparticle cluster gas sensor: Pt activated SnO2 nanoparticles for NH3 detection with ultrahigh sensitivity. Nanoscale 7, 14872–14880 (2015).

Majhi, S. M. et al. Au@NiO core-shell nanoparticles as a p-type gas sensor: Novel synthesis, characterization, and their gas sensing properties with sensing mechanism. Sens. Actuators, B 268, 223–231 (2018).

Kim, J. D., Yun, J. H., Song, J. W. & Han, C. S. The spontaneous metal-sitting structure on carbon nanotube arrays positioned by inkjet printing for wafer-scale production of high sensitive gas sensor units. Sens. Actuators, B 135, 587–591 (2009).

Feng, Q., Li, X. & Wang, J. Percolation effect of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) on ammonia sensing of rGO-SnO2 composite based sensor. Sens. Actuators, B 243, 1115–1126 (2017).

Siddiqui, G. U. et al. Wide range highly sensitive relative humidity sensor based on series combination of MoS2 and PEDOT:PSS sensors array. Sens. Actuators, B 266, 354–363 (2018).

Wang, K. et al. Inorganic–organic pn heterojunction nanotree arrays for a high-sensitivity diode humidity sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 5825–5831 (2013).

Yuan, H. et al. ZnO nanosheets abundant in oxygen vacancies derived from metal‐organic frameworks for ppb‐level gas sensing. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807161 (2019).

Gui, Y. et al. P-type Co3O4 nanoarrays decorated on the surface of n-type flower-like WO3 nanosheets for high-performance gas sensing. Sens. Actuators, B 288, 104–112 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Novel SnO2@ZnO hierarchical nanostructures for highly sensitive and selective NO2 gas sensing. Sens. Actuators, B 257, 714–727 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. In situ growth of NiO@SnO2 hierarchical nanostructures for high performance H2S sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 44829–44836 (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. An acetone gas sensor based on nanosized Pt-loaded Fe2O3 nanocubes. Sens. Actuators, B 290, 59–67 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Multilevel effective heterojunctions based on SnO2/ZnO 1D fibrous hierarchical structure with unique interface electronic effects. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 31551–31561 (2019).

Miller, D. R., Akbar, S. A. & Morris, P. A. Nanoscale metal oxide-based heterojunctions for gas sensing: a review. Sens. Actuators, B 204, 250–272 (2014).

Zappa, D. et al. “Metal oxide -based heterostructures for gas sensors”- a review. Anal. Chim. Acta 1039, 1–23 (2018).

Mercante, L. A., Andre, R. S., Mattoso, L. H. C. & Correa, D. S. Electrospun ceramic nanofibers and hybrid-nanofiber composites for gas sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 4026–4042 (2019).

Yu, H. et al. Spatial variation of surface water quality in Hangzhou section of Qiantang river during different water periods. Yellow River, 08, (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Advances in designs and mechanisms of semiconducting metal oxide nanostructures for high-precision gas sensors operated at room temperature. Mater. Horiz. 6, 470–506 (2019).

Ahmad, R. et al. Recent progress and perspectives of gas sensors based on vertically oriented ZnO nanomaterials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 270, 1–27 (2019).

Yuliarto, B., Gumilar, G. & Septiani, N. L. W. SnO2 nanostructure as pollutant gas sensors: synthesis, sensing performances, and mechanism. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1–14 (2015).

Gurlo, A. Nanosensors: towards morphological control of gas sensing activity. SnO2, In2O3, ZnO and WO3 case studies. Nanoscale 3, 154–165 (2011).

Koo, W. T. et al. Chemiresistive hydrogen sensors: fundamentals, recent advances, and challenges. ACS Nano 14, 14284–14322 (2020).

Al-Hashem, M., Akbar, S. & Morris, P. Role of oxygen vacancies in nanostructured metal-oxide gas sensors: a review. Sens. Actuators, B 301, 126845 (2019).

Ji, H., Zeng, W. & Li, Y. Gas sensing mechanisms of metal oxide semiconductors: a focus review. Nanoscale 11, 22664–22684 (2019).

Chen, S., Gao, N., Bunes, B. R. & Zang, L. Tunable nanofibril heterojunctions for controlling interfacial charge transfer in chemiresistive gas sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 13709–13735 (2019).

Wang, B., Nisar, J. & Ahuja, R. Molecular simulation for gas adsorption at NiO (100) surface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 5691–5697 (2012).

Kida, T. et al. Pore and particle size control of gas sensing films using SnO2 nanoparticles synthesized by seed-mediated growth: design of highly sensitive gas sensors. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 17574–17582 (2013).

Bulemo, P. M., Cho, H. J., Kim, D. H. & Kim, I. D. Facile synthesis of Pt-functionalized meso/macroporous SnO2 hollow spheres through in situ templating with SiO2 for H2S sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 18183–18191 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Sputtered SnO2:NiO thin films on self-assembled Au nanoparticle arrays for MEMS compatible NO2 gas sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 278, 28–38 (2019).

Xu, C., Tamaki, J., Miura, N. & Yamazoe, N. Grain size effects on gas sensitivity of porous SnO2-based elements. Sens. Actuators, B 3, 147–155 (1991).

Cui, S. et al. Ultrasensitive chemical sensing through facile tuning defects and functional groups in reduced graphene oxide. Anal. Chem. 86, 7516–7522 (2014).

Bandara, N., Jayathilaka, C., Dissanayaka, D. & Jayanetti, S. Temperature effects on gas sensing properties of electrodeposited chlorine doped and undoped n-type cuprous oxide thin films. J. Sens. Technol. 04, 119–126 (2014).

Gad, A. et al. Integrated strategy toward self-powering and selectivity tuning of semiconductor gas sensors. ACS Sens 1, 1256–1264 (2016).

Liu, L. et al. A photovoltaic self-powered gas sensor based on a single-walled carbon nanotube/Si heterojunction. Nanoscale 9, 18579–18583 (2017).

Jose, A. S., Prajwal, K., Chowdhury, P. & Barshilia, H. C. Sputter deposited p-NiO/n-SnO2 porous thin film heterojunction based NO2 sensor with high selectivity and fast response. Sens. Actuators, B 310, 127830 (2020).

Kumar, A., Sanger, A., Kumar, A. & Chandra, R. Fast response ammonia sensors based on TiO2 and NiO nanostructured bilayer thin films. RSC Adv. 6, 77636–77643 (2016).

Barsan, N., Koziej, D. & Weimar, U. Metal oxide-based gas sensor research: How to? Sens. Actuators, B 121, 18–35 (2007).

Batzill, M. & Diebold, U. The surface and materials science of tin oxide. Prog. Surf. Sci. 79, 47–154 (2005).

Lee, J.-H. Gas sensors using hierarchical and hollow oxide nanostructures: overview. Sens. Actuators, B 140, 319–336 (2009).

Comini, E. et al. Stable and highly sensitive gas sensors based on semiconducting oxide nanobelts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 1869–1871 (2002).

Sun, G. J. et al. H2S gas sensing properties of Fe2O3 nanoparticle-decorated NiO nanoplate sensors. Surf. Coat. Technol. 307, 1088–1095 (2016).

Zhou, X. et al. Crystal-defect-dependent gas-sensing mechanism of the single ZnO nanowire sensors. ACS Sens 3, 2385–2393 (2018).

Choi, P. G., Fuchigami, T., Kakimoto, K.-I. & Masuda, Y. Effect of crystal defect on gas sensing properties of Co3O4 nanoparticles. ACS Sens 5, 1665–1673 (2020).

Motaung, D. E. et al. Ultra-high sensitive and selective H2 gas sensor manifested by interface of n-n heterostructure of CeO2-SnO2 nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators, B 254, 984–995 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Controlled synthesis and enhanced catalytic and gas‐sensing properties of tin dioxide nanoparticles with exposed high-energy facets. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 2283–2289 (2012).

Bi, H. et al. Morphology-controlled synthesis of CeO2 nanocrystals and their facet-dependent gas sensing properties. Sens. Actuators, B 330, 129374 (2021).

Han, X. et al. Synthesis of tin dioxide octahedral nanoparticles with exposed high‐energy {221} facets and enhanced gas‐sensing properties. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 48, 9180–9183 (2009).

Yamazoe, N. Toward innovations of gas sensor technology. Sens. Actuators, B 108, 2–14 (2005).

Katoch, A., Abideen, Z. U., Kim, H. W. & Kim, S. S. Grain-size-tuned highly H2-selective chemiresistive sensors based on ZnO-SnO2 composite nanofibers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2486–2494 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Grain‐boundary‐induced drastic sensing performance enhancement of polycrystalline‐microwire printed gas sensors. Adv. Mater. 31, 1804583 (2019).

Sakai, G., Matsunaga, N., Shimanoe, K. & Yamazoe, N. Theory of gas-diffusion controlled sensitivity for thin film semiconductor gas sensor. Sens. Actuators, B 80, 125–131 (2001).

Shimanoe, K., Yuasa, M., Kida, T., Yamazoe, N. In 2011 IEEE Nanotechnology Materials and Devices Conference. 38–43 (IEEE).

Adamu, B. I. et al. p-p heterojunction sensors of p-Cu3Mo2O9 micro/nanorods vertically grown on p-CuO layers for room-temperature ultrasensitive and fast recoverable detection of NO2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 8411–8421 (2020).

Yan, W. et al. MOF-derived porous hollow Co3O4@ZnO cages for high-performance MEMS trimethylamine sensors. ACS Sens 6, 2613–2621 (2021).

Lou, C. et al. Fe2O3-sensitized SnO2 nanosheets via atomic layer deposition for sensitive formaldehyde detection. Sens. Actuators, B 345, 130429 (2021).

Zhang, R. et al. Rational design and tunable synthesis of Co3O4 nanoparticle-incorporating into In2O3 one-dimensional ribbon as effective sensing material for gas detection. Sens. Actuators, B 310, (2020).

Kim, J. H. et al. Optimization and gas sensing mechanism of n-SnO2-p-Co3O4 composite nanofibers. Sens. Actuators, B 248, 500–511 (2017).

Kim, J. H. et al. Enhancement of CO and NO2 sensing in n-SnO2-p-Cu2O core-shell nanofibers by shell optimization. J. Hazard. Mater. 376, 68–82 (2019).

Kim, J. H. & Kim, S. S. Realization of ppb-Scale toluene-sensing abilities with Pt-functionalized SnO2-ZnO core-shell nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 17199–17208 (2015).

Walker, J. M., Akbar, S. A. & Morris, P. A. Synergistic effects in gas sensing semiconducting oxide nano-heterostructures: a review. Sens. Actuators, B 286, 624–640 (2019).

Naik, A., Parkin, I. & Binions, R. Gas sensing studies of an n-n hetero-junction array based on SnO2 and ZnO. Compos. Chemosens. 4, 3 (2016).

Li, B. et al. Core-shell structure of ZnO/Co3O4 composites derived from bimetallic-organic frameworks with superior sensing performance for ethanol gas. Appl. Surf. Sci. 475, 700–709 (2019).

Mulmi, S. & Thangadurai, V. Semiconducting SnO2-TiO2 (ST) composites for detection of SO2 gas. Ionics 22, 1927–1935 (2016).

Li, S. et al. Metal-Organic frameworks-derived bamboo-like CuO/In2O3 Heterostructure for high-performance H2S gas sensor with Low operating temperature. Sens. Actuators, B 310, 127828 (2020).

Xiong, Y. et al. ZIF-derived porous ZnO-Co3O4 hollow polyhedrons heterostructure with highly enhanced ethanol detection performance. Sens. Actuators, B 253, 523–532 (2017).

Wei, Q. et al. Spindle-like Fe2O3/ZnFe2O4 porous nanocomposites derived from metal-organic frameworks with excellent sensing performance towards triethylamine. Sens. Actuators, B 317, 128205 (2020).

Liu, D., Wan, J., Pang, G. & Tang, Z. Hollow metal–organic‐framework micro/nanostructures and their derivatives: emerging multifunctional materials. Adv. Mater. 31, 1803291 (2019).

Gao, X. et al. Porous MoO3/SnO2 Nanoflakes with n–n Junctions for Sensing H2S. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 2418–2425 (2019).

Shaposhnik, D. et al. Hydrogen sensors on the basis of SnO2-TiO2 systems. Sens. Actuators, B 174, 527–534 (2012).

Staerz, A. et al. Dominant role of heterojunctions in gas sensing with composite materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 21127–21132 (2020).

Yamazoe, N. & Shimanoe, K. Basic approach to the transducer function of oxide semiconductor gas sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 160, 1352–1362 (2011).

Yamazoe, N. & Shimanoe, K. Proposal of contact potential promoted oxide semiconductor gas sensor. Sens. Actuators, B 187, 162–167 (2013).

Xu, Y. et al. p-p heterojunction composite of NiFe2O4 nanoparticles-decorated NiO nanosheets for acetone gas detection. Mater. Lett. 270, 127728 (2020).

Dong, S. et al. Multi-dimensional templated synthesis of hierarchical Fe2O3/NiO composites and their superior ethanol sensing properties promoted by nanoscale p-n heterojunctions. Dalton Trans. 49, 1300–1310 (2020).

Yoon, J. W. et al. Kilogram-scale synthesis of Pd-loaded quintupleshelled Co3O4 microreactors and their application to ultrasensitive and ultraselective detection of methylbenzenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 7717–7723 (2015).

Huo, L. et al. Modulation of potential barrier heights in Co3O4/SnO2 heterojunctions for highly H2-selective sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 244, 694–700 (2017).

Yin, X.-T. et al. Ultra-high selectivity of H2 over CO with a p-n nanojunction based gas sensors and its mechanism. Sens. Actuators, B 319, 128330 (2020).

Katoch, A. et al. Bifunctional sensing mechanism of SnO2–ZnO composite nanofibers for drastically enhancing the sensing behavior in H2 gas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 11351–11358 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Hydrogen-induced metallization of zinc oxide (2(11)over-bar-0) surface and nanowires: the effect of curvature. Phys. Rev. B 77, 245303 (2008).

Wang, Y. et al. Hydrogen Induced Metallicity on the ZnO (1010) Surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 266104 (2005).

Ramakrishnan, V. et al. Porous, n-p type ultra-long, ZnO@Bi2O3 heterojunction nanorods-based NO2 gas sensor: new insights towards charge transport characteristics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 7524–7536 (2020).