Abstract

Bistability is widely exploited to demonstrate all-optical signal processing and light-based computing. The standard paradigm of switching between two steady states corresponding to “0” and “1” bits is based on the rule that a transition occurs when the signal pulse intensity overcomes the bistability threshold, and otherwise, the system remains in the initial state. Here, we break with this concept by revealing the phenomenon of indefinite switching in which the eventual steady state of a resonant bistable system is transformed into a nontrivial function of signal pulse parameters for moderately intense signal pulses. The essential nonlinearity of the indefinite switching allows realization of well-protected cryptographic algorithms with a single bistable element in contrast to software-assisted cryptographic protocols that require thousands of logic gates. As a proof of concept, we demonstrate stream deciphering of the word “enigma” by means of an indefinitely switchable optical nanoantenna. An extremely high bitrate ranging from ~0.1 to 1 terabits per second and a small size make such systems promising as basic elements for all-optical cryptographic architectures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuous growth in communication traffic drives new demands in novel cryptographic techniques that can supply reliable security of information exchange at a high rate. Many methods have been actively proposed and explored. Although the majority of modern solutions focus on development of software algorithms1,2, hardware realizations offer an additional and valuable degree of security. Recent examples of such approaches include digital metamaterials3 and metasurfaces4,5,6, which consider two elemental media with a strong contrast in the electromagnetic response as building blocks (treated as “metamaterial bits”). The direct correspondence between the spatial structuring of such information bits and the electromagnetic properties of the entire system leads to a number of promising functionalities, such as information encoding in the radiation field patterns5 as well as analogous7 and digital4 computations. Another actively developed realm involves securing optical information in images via linear and nonlinear holography8,9. However, all of these techniques typically require bulky structures and complicated programming algorithms8,10,11, which restrict their performance.

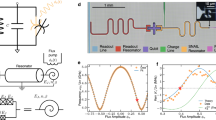

Alternative strategies for all-optical information processing apply bistability. From a physical viewpoint, bistability occurs when a free-energy landscape of the system contains two minima separated by one maximum12. To switch between the minima, the system is disturbed with a form of activation energy, which is typically supplied by a large-amplitude input signal. For the all-optical bistable switchers reported thus far, this type of transition appears when the signal pulse intensity slightly overcomes the bistability threshold and the system returns to the initial state for weaker pulses12,13,14,15. Here, we show that this paradigm can be changed for sufficiently strong signal pulses that induce the activation energy to a much larger extent than the local maxima of the free energy. As a result, the eventual steady state is transformed to a nontrivial function of the pulse intensity, phase, and duration, as shown in Fig. 1a. This phenomenon of indefinite switching is used to demonstrate cryptographically secure stream encryption.

a Switching diagram calculated by Eqs. 1 and 3. Polar angle and radii correspond to the signal pulse phase and intensity. Yellow and pink areas associated with “0” and “1” bits denote the eventual system state after disturbance by a signal pulse. The initial state is set to “1”. The grey shadow area marks the regime of operation for conventional bistable switchers. A transition appears when the intensity of a signal pulse with an appropriate phase slightly overcomes the bistability threshold and the system remains in the initial position for weaker pulses, regardless of the pulse phase. The indefinite switching regime arises for stronger signal pulse intensities, transforming the eventual steady state into a nonlinear function of the pulse parameters. b Schematic demonstration of stream deciphering by indefinite switching implemented with a bistable heterodimer. Formed by continuous-wave background radiation, the heterodimer scattering pattern can take on omnidirectional or backward scattering states corresponding to “1” and “0” bits. Ciphertext, a sequence of signal pulses with distinct phases and intensities, is decoded into dual-bit plaintext by switching the nanoantenna scattering pattern, which is measured with aid of two synchronized photodiodes. The nonlinearity in the relationship between ciphertext and plaintext is supplied by indefinite switching, which warrants strong cryptographic security

Stream ciphers encrypt and decrypt bits individually using a secret key (a string of bits). To make ciphering sufficiently reliable, cryptographic devices must combine the randomness of a securing key and nonlinearity in the relationship between plaintext and ciphertext1. Importantly, vanishing nonlinearity results in a weak cryptographical security even when one has a random key with appropriate statistical properties because it is sufficient to know only a small portion of a message to fully unwrap the secret key by solving the linear system of equations (algebraic attack). Software-assisted cryptographic algorithms exploit combinations of many Boolean operations and shift registers to achieve nonlinearity. This approach calls for cascading of thousands of logic gates, which limits compactness and performance for such cryptographic architectures. For example, one of the fastest and most efficient modern stream ciphers, trivium, occupies approximately 4000 logic gates and encrypts at a maximal bitrate of 2 Gb s−11. In contrast, indefinite switching naturally brings nonlinearity into the relationship between plaintext and ciphertext at the level of a single optical bistable nanoantenna. The ultrafast switching time and small size render such systems promising basic elements for novel lightweight cryptographic protocols operating at a Tb s−1 bitrate.

In general, any side in a cryptographically secured data exchange process performs ciphering and deciphering procedures. Although these operations are the mathematical inverse of each other, they can be physically implemented by different devices. Here, we focus on deciphering by indefinite switching in an optical bistable nanoantenna (receiver), assuming data encoding in the intensities and phases of coherent signal pulses generated by an external laser system (sender).

As proof of concept, we consider scattering of a laser beam by a pair of nanoparticles (Fig. 1b). We assume that one nanoparticle in the dimer possesses a Kerr-type nonlinearity combined with a resonant response. In practice, such a nanoparticle can be constructed, for example, using any plasmonic material16,17,18. A surface plasmon resonance appears together with a strong cubic susceptibility for such materials as silver, gold and graphene19,20,21. This configuration allows driving of bistability at a moderate light power due to the strength of the nonlinear response reached via the resonance. The second nanoparticle is assumed to be linear and nonresonant and plays a role of a director to shape the directivity of the dimer scattering pattern.

Continuous-wave background radiation creates the desired nanoantenna energy landscape, giving rise to bistability, which together with the asymmetric dimer structure allows switching of the scattering pattern from an omnidirectional to a backward-scattered regime and back by illuminating the system with high-power signal pulses. Being easily distinguished in an experiment, such scattering states are associated with “0” and “1”. With the aid of the general theoretical model, which describes the temporal transitions between these states, we show how to reach the regime of indefinite switching and elucidate its applications for ultrafast and efficient stream ciphering.

Results

Indefinite switching: theoretical framework

To perform a rigorous theoretical analysis of the system, the optical responses of subwavelength nanoparticles are treated within the point-dipole approximation. The dimer consists of a pair of particles in which one is resonant and nonlinear, and the second is nonresonant and linear (for the purpose of the directivity pattern switching). When the dimer is illuminated by a wave with the carrier frequency in the vicinity of the resonance (ω0), the first nanoparticle acts as a resonating oscillator with a slow (compared with the carrier) inertial response, whereas the time delay in the response of the second nanoparticle can be neglected because it is assumed to be nonresonant and dispersionless. With these considerations, we apply the dispersion relation method22, which formulates the dynamic problem as a set of coupled equations for the slowly varying amplitudes of the nanoparticle dipole moments P1 and P2, written in dimensionless units as follows:

In this formulation, E = Ep + Es is the slow varying amplitude of the external light field containing pumping continuous-wave background radiation Ep and signal pulse Es contributions, Ω = (ω−ω0−δω)/ω0 is the driving frequency detuning from the resonant value, δω is the resonance frequency shift due to the dipole–dipole coupling between the nanoparticles, γ describes the thermal and radiation losses of the resonant nanoparticle, \(k_0 = \left( {\omega _0/c} \right)\sqrt {\varepsilon _h}\), c is the speed of light in vacuo, εh is the permittivity of the host media, η is the dipole-dipole coupling between nanoparticles, ς is the normalized director particle polarizability, and τ = ω0t is the dimensionless time. The model derivation and detailed definitions of all these quantities are available in the Methods.

The steady-state solution of Eq. 1 is written as follows

The nanoparticle polarizations P1 and P2 turn into three-valued functions of frequency with two stable branches and one unstable branch when \(\Omega < - \sqrt {3\gamma }\). These branches feature different scattering patterns that can be found by substitution of Eq. 2 into the general expression for the normalized scattering pattern (far-field intensity) of a couple of dipoles:23

where φ and θ are the spherical azimuthal and polar angles, and Δκ denotes the phase shift between the dipoles. Because the director particle is nonresonant, efficient interparticle coupling occurs only when k0d << 1. In this case, the shape of the scattering pattern is defined predominantly by Δκ, altering the behavior from dipole-like for Δκ∼0 to pronounced directional shape for Δκ∼π24. Considering the negligible dispersion of the second nanoparticle, Δκ is tunable mainly due to the resonance of the first nanoparticle. We also introduce the front-to-back scattering ratio as U(π/2,π/2)/U(3π/2,π/2) to supply quantitative information on the dimer scattering properties.

Indefinite switching: realization

The model represented by Eq. 1 is quite general and can be attributed to many different physical systems and engineering realizations. To make a qualitative estimate, we choose the following scenario: the heterodimer is realized as a pair of spherical nanoparticles made of graphene-wrapped ZnSe and silicon and placed in a free space. Graphene-based bistable switchers currently attract a great amount of attention25,26,27. The nanoparticle radii and the center-to-center distance are RSi = 120 nm and RZnSe = 50 nm and d = 400 nm. We adjusted the parameters of the structure to obtain ħω0 = 0.133 eV, which corresponds to the wavelength of a CO2 laser at 9.32 µm (see further details in Methods).

The typical bistable response of the heterodimer is shown in Fig. 2a. Once the light intensity enters the bistability domain, the system demonstrates two stable solutions with omnidirectional dipole-like and pronounced backward scattering patterns, which we associate with information bits “1” and “0”, respectively. The sharpest contrast in the front-to-back ratio between these states (~30 dB) appears for the intensity 3.9 MW cm−2 and Δκ = 0.1 × π and 1.08 × π for the “1” and “0” bits, in agreement with Eq. 3. We consider switching between these states, which, in practice, can be measured with a couple of synchronized photodiodes (Fig. 1b).

a Steady-state front-to-back scattering ratio as a function of the background intensity given by Eqs. 2 and 3 with the detuning Ω = −0.12. The bistability thresholds correspond to intensities 0.8 and 25 MW cm−2 (indicated by dotted lines in b and c). The inserts show the scattering patterns at an intensity of 3.9 MW cm−2 for which the steady states are marked by purple circles. Arrows denote the schematic transitions from one branch to another. The unstable branch is marked by the green dashed curve. b Demonstration of conventional temporal switching from the upper branch to the lower branch and back when the signal pulses slightly overcome the bistability thresholds. c The switching-off regime for signal pulses with peak intensities much stronger bistability thresholds. In b and c, the driving light intensity and the resulted front-to-back scattering ratio are shown in the bottom and top rows, respectively. The pulse peak intensities and phases are (31.9 MW cm−2, 0), (0.09 MW cm−2, π) and (86.6 MW cm−2, 0), (1.1 MW cm−2, π) for (b) and (c), respectively. The pulse duration is 0.3 ps

To induce transition from “0” to “1”, following the common paradigm, one should illuminate the dimer with a signal pulse that is in phase with the background radiation and whose peak intensity together with the background intensity overcomes the high-intensity bistability threshold. An opposite transition from “1” to “0” is stimulated if one drives the system using an out-of-phase signal pulse with peak intensity, which is sufficiently large to decrease the total external field below the low-intensity bistability threshold. Figure 2b shows this type of switching, obtained by direct numerical simulation of Eq. 1. We assume that the background field slowly increases to the saturation level E0 as Ep = (2E0/π) arctan(τ/Δτ) (Δτ is the characteristic time of reaching the saturation), and the phase-locked signal pulse follows the Gaussian shape Es = Epeakexp[−(τ−τ0)2/δ2 + iΔΦ], where Epeak is the peak amplitude of the pulse, τ0 defines the pulse temporal localization, δ is the pulse half-width, and ΔΦ is the phase shift between the pulse and the background radiation. In practice, similar driving is widely used to realize coherent control over excitations in different nanostructures28,29,30.

Surprisingly, we reveal that the system does not obey this rule when the peak pulse intensity grows considerably higher than the bistability thresholds. Specifically, the nanoantenna can transit to the counterpart state or remain in the initial position, depending on the signal pulse peak intensity, phase and duration. An example of such indefinite switching is shown in Fig. 2c when the switching is cancelled even though the signal peak intensities are significantly above the bistability thresholds.

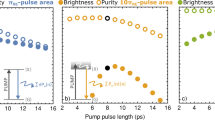

Figure 3 shows the switching diagrams obtained by numerical simulations of Eq. 1. Specifically, we found the eventual heterodimer steady state by variations in the peak intensity, phase and duration of the signal pulse for the two initial states shown schematically in Fig. 3a, b. When the pulse intensity remains comparatively low, the system obeys the conventional switching regime described above (Fig. 1a). However, as the intensity grows, the final state turns into a nontrivial function of the pulse characteristics due to an intricate interplay between the system inertia and nonlinearity and the stimuli, as shown in Fig. 3c–j. Once the signal pulse passes, the system might be attracted by either the “0” or “1” state as a result of combined action of all of these factors. Additionally, the inertia yields the considerable increase of the switching thresholds with respect to the steady state prediction when the time of flight of a signal pulse decreases to below the decay time of oscillations, which is estimated as 0.3 ps (see Methods) (Fig. 3g, h).

a, b Schematics of the system energy profile. Minima correspond to the stable steady states with omnidirectional and backward scattering patterns. The magenta circle indicates the system initial state. The results shown in the upper (c, e, g, and i) and lower (d, f, h, and j) rows were obtained for the initial states depicted in (a) and (b), respectively. In (c) and (d), the color denotes the front-to-back scattering ratio in the final state. The azimuthal angle and the polar radius mark the phase (with respect to the background radiation) and intensity (in MW cm-2) of the signal pulse. In (e), (f), (i) and (j), the color shows the characteristic time required to reach the eventual steady state. The pulse duration for (c)–(f) is 0.4 ps. Panels (g)–(j) demonstrate the transitional diagrams in terms of signal pulse intensity and duration. For (g) and (i), the signal pulse is in phase with the background radiation, and for (h) and (j), it is out-of-phase. Other parameters are the same as in Fig. 2. The horizontal dashed lines in (g) and (h) mark the upper and lower steady-state bistability thresholds with respect to the background intensity

The important characteristic of indefinite switching is the transitional time required to reach the eventual state, which also appears to be signal-pulse-dependent (Fig. 3e, f, i, j). Obviously, this time scale is minimal when the system remains in the initial position and increases once a transition occurs. These dependencies should be considered as the main limitation on the bitrate of information processing with the heterodimer because the temporal separation between the signal pulses must be longer than the system switching time to distinguish distinct bits.

Decryption with indefinite switching

An indefinitely switchable nanoantenna serves as a nonlinear function that converts incoming signal pulses with different intensities, phases, and durations into a binary output signal such that by relying on the switching diagrams in Fig. 3, one can build up a cipher, which allows conversion of a message hidden in a sequence of signal pulses (ciphertext) into a dual-bit format (plaintext). To demonstrate information decryption in this manner, we take 9 points belonging to the Archimedean spiral \(\rho = \frac{{300}}{{3\pi }}\Delta \Phi\) [MW cm−2] (the encryption key) at the phase-intensity switching map, as shown in Fig. 4a, b, with the following parameters: 1–(50 MW cm−2, π/2), 2–(75 MW cm−2, 3π/4), 3–(150 MW cm−2, 3π/2), 4–(175 MW cm−2, 7π/4), 5–(200 MW cm−2, 0), 6–(225 MW cm−2, π/4), 7–(275 MW cm−2, 3π/4), 8–(287 MW cm−2, 7π/8), and 9–(300 MW cm−2, π). Each of these pulses might drive switching to the counterpart state or may not, depending on the current dimer state. As the message, we choose the word “enigma”, which in a dual-bit ASCII (American standard code for information interchange) format is written as “01100101 01101110 01101001 01100111 01101101 01100001”.

a, b Switching diagrams from Figs. 3c, d with the encryption key, i.e., the points belonging to the Archimedean spiral \(\rho = \frac{{300}}{{3\pi }}\Delta \Phi\) [MW cm−2], shown in blue. c Driving light field containing the background radiation and the sequence of ciphertext pulses as a function of time. The numbers above the figure denote the signal pulses from (a) and (b). d Resulting front-to-back scattering ratio for the excitation shown in (c). The numbers above the figure show the eventual dual-bit code corresponds to the word “enigma”

We launch a sequence of chosen signal pulses (Fig. 4c) with a fixed interval of 7.4 ps between them, which we adjusted based on Fig. 3e, f to avoid bit overlap. We stress that for successful decoding, one must appropriately set the background radiation intensity, the frequency detuning and the initial state. Figure 4d shows the resulting temporal response of the nanoantenna, which exactly reproduces the dual-bit code corresponding to the message. It is instructive to note that the bitrate of the demonstrated stream decryption is as fast as 240 light periods per one-bit processing or 0.13 Tb s−1. This quantity is predominantly defined by the resonant frequency and the quality factor, which is ~30 for the considered system. Remarkably, the dipole plasmonic resonance in metallic nanoantennas is characterized by a similar quality factor. However, ω0 for such structures lies in the visible domain. Hence, for metallic-based nanoantennas, one can expect a bit rate of approximately several Tb s−1.

Discussion

The nonlinearity of indefinite-switching-assisted encryption means that a given plaintext bit can be encoded by a variety of ciphertext signal pulses, yielding an infinite number of ways to relate the ciphertext to the plaintext. Additional randomization of coding pulses renders the problem of identifying the correct coding key extremely challenging. It should be noted that this crucial requirement for reliability of cryptographic protocols is reached with only a single indefinitely switchable nanoantenna in contrast to software-assisted solutions, which are based on the use of thousands of logic gates.

The information exchange via indefinite switching relies on the sender’s encoding algorithm (encryption key) and the sum of the receiver’s system parameters (decryption key), which include the geometrical and material properties of the nanoantenna, the background radiation intensity, the frequency detuning and the initial state, and all of those parameters must be set prior to the deciphering procedure. Independent manipulations over these keys permit integration of indefinite switching and existing cryptographic principles.

In case of symmetric-key cryptography, all parties use the same encryption key and the same decryption key. Hence, the parties should have identical indefinitely switchable nanoantennas, and the keys should be shared in advance (before every encryption session) via a secured channel. Moreover, the background radiation intensity, frequency detuning and initial state play the role of the initialization vector (IV), which should take on a new random value for every encryption session. As the IV and the encryption key must be coherent, this procedure warrants that the encryption key must always be randomly different even if one encrypts the same message several times (semantic security)1,2.

In asymmetric-key cryptography, the sides share only a public (encryption) key, which can be widely disseminated, and the private (decryption) key, which is different for every side, is held in secret. The pairing of these keys is based on the formalism of one-way functions, i.e., functions that are easy to compute on every input but computationally difficult to invert given the image of a random input. One-way functions are fundamental tools in personal identification, authentication, digital signatures and many other data security applications1,2. Indefinite switching can also operate as a one-way function since a given encoding algorithm can match many different decryption keys. Thus, once the public key is known, each party should use an individual nanoantenna with distinct properties to generate its own private key.

Importantly, the essential requirement for every cryptographic scheme is to maintain the carrier frequencies of the optical signals and the background radiation as equal. Unsynchronized light driving results in beating, which can be described as the following exchange in Eq. 1 Es→Es exp(iΔΨ(τ)τ), where ΔΨ(τ) is the frequency drift between the background radiation and a signal pulse in time. Obviously, this effect can lead to error switching unless the drift is much slower than the time duration of a decryption session T, i.e., ΔΨ(τ)T<<π. Another potential source of errors is nanoantenna damage owing to overheating, which might change its optical properties. However, a recent study31 has shown that coating of plasmonic nanoantennas with a protective Al2O3 thin layer gives rise to unchanged both linear and nonlinear responses during 10-min illumination at a pulse repetition rate of 44 MHz and a pulse intensity 0.6 GW cm−2. This observation allows us to believe that this issue is also avoidable.

To conclude, we have shown that a bistable optical heterodimer features indefinite switching, i.e., in response to a sufficiently strong signal pulse, the system can eventually transit to a counterpart steady state or remain in the initial position, depending on the pulse parameters. The essential nonlinearity of this operation makes indefinite-switching-enabled stream ciphering immune to algebraic attacks. In contrast to commonly used cryptographic algorithms requiring thousands of logic gates, indefinite-switching-assisted cryptographic protocols can be realized with a single bistable element, benefiting from compactness and performance. We demonstrated this principle by decrypting the word “enigma” with the remarkably high bit rate of 240 light periods per one-bit processing (or 0.13 Tb s−1).

Our findings can be transferred to a variety of bistable systems, thus supplying great capacity for practical use. In particular, the presented general model is straightforwardly applicable to a broad range of nanoantennas, including plasmonic32, core-shell33,34,35 and high-index nanoparticles36 as well as graphene flakes37. We believe indefinite switching can also be obtained in a wide range of other resonant bistable system, including multilayered structures38,39, photonic crystal waveguides15,40, and polaritonic cavities41. Many of these elements are readily available for integration in existing nanophotonic circuitry14,42 and optical fibers25,43, paving the way towards numerous opportunities for implementation of indefinite-switching-assisted cryptographic protocols on well-developed platforms. Additional highly important cryptographic functionalities, such as random secure key generation with appropriate statistical properties and integration of many bistable elements in a single device for parallelization, could enable engineering of all-optical cryptographic architectures operating at ultrafast speeds at the nanoscale.

Methods

General model derivation

We assume that the dipole terms dominate in the nanoparticle responses and that quantum finite-size effects are negligible. The Kerr-like nonlinearity can be introduced via either the permittivity for nonlinear media as εNL = εL + Δε or the conductivity for graphene σNL = σL + Δσ. Here, nonlinear corrections \(\Delta \varepsilon = \chi ^{(3)}\left| {{\mathbf{E}}^{(in)}} \right|^2\) and \(\Delta \sigma = \sigma ^{(3)}\left| {{\mathbf{E}}^{(in)}} \right|^2\) contain the local electric field inside the nonlinear media E(in), the cubic susceptibility χ(3) and conductivity σ(3). The type of nonlinearity is assumed to be focusing since it was measured for the majority of highly nonlinear materials19,20. However, one can easily adjust our derivations for the defocusing nonlinearity as well.

We present the Fourier transforms of the nanoparticle electric-dipole moments as follows

where Ez(ex) is the driving electric field, and the nanoparticle polarizabilities α1 and α2 are given by the geometry of a specific system and analytically or numerically calculated or experimentally measured. The resonance frequency ω0 corresponds to the maximal nanoparticle polarizability α1. By appropriate fitting of the material composition, the nanoparticle shape and the host medium, one can tune this frequency from the visible range to the THz spectral domain. The electromagnetic Green’s function, which describes the dipole-dipole interaction between the particles, is written as follows

where d is the center-to-center distance between the nanoparticles, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity and \(k = \left( {\omega /c} \right)\sqrt {\varepsilon _h}\) is the wavenumber in the host medium. Hereinafter, we assume harmonic dependence on time as exp[−iωt].

The dispersion relation method is based on the assumption that nonlinearity, losses, frequency detuning from resonance, and broadening of the particle polarization spectrum (due to temporal dynamics) are taken in the first order of perturbation, i.e., Δε<<εL, ImεL<<ReεL, (ω-ω0)/ω0<<144. With this consideration, we decompose α1−1(ω) in the vicinity of ω0,

In this formulation, we used the fact that Re{α1−1} = 0 at resonance in a lossless case. We disregard the weak frequency-induced variations in the director polarizability α2 and the dipole coupling field and accept α2 = α2(ω0) and G = G(ω0).

Next, we assume that the nonlinear correction Δε does not change the structure of the particle eigenmode and results in the field-self action effect only45 such that one can replace the spatially dependent local field in the graphene layer E(in) with its average value

where V is the volume of the nonlinear media. We express the nonlinear correction for the permittivity as follows

where \(\psi = \left\langle {\left| {{\mathbf{E}}^{(in)}} \right|^2} \right\rangle /\left| {{\mathbf{E}}^{(ex)}} \right|^2\) is the field enhancement factor at resonance.

Using these considerations, we substitute Eqs. 5 and 6 into Eq. 4 and derive Eq. 1. The normalized quantities are given by the following

To obtain the model for a graphene-based nanoantenna, one should make the following exchange: εL→σL, Δε→Δσ, and χ(3)→σ(3).

Specific details of the heterodimer containing silicon and graphene-wrapped ZnSe nanoparticles

We assume that the heterodimer is placed in air with permittivity εh = 1 and contains a couple of spherical nanoparticles made of silicon and graphene-wrapped ZnSe. The nanoparticle radii and the center-to-center distance are R1 = RZnSe = 50 nm and R2 = RSi = 120 nm and d = 400 nm. Because the gap between nanoparticle surfaces exceeds min{RSi,RZnSe} and the light wavelength is much larger than the nanoparticle sizes, one can neglect boundary, nonlocal, and quantum finite-size effects46 and apply the point-dipole approximation47. In the wavelength domain of 2.5–10 μm, dispersion for both silicon and ZnSe is insignificant such that we take their permittivities as εSi ≈ 11.748 and εZnSe ≈ 5.749. The linear graphene conductivity can be expressed for photon energies smaller than the Fermi energy in terms of the Drude model as follows20

where e is the electron charge, ℏ is the Planck constant, ξ is the relaxation time for intraband transitions, \({\it{{\rm E}}}_F = \hbar V_F\sqrt {\pi n}\) is the Fermi energy, n is the doping electron density, and VF ≈ c/300 is the Fermi velocity. For high-quality graphene samples, one can estimate ξ = 0.3 ps and EF = 0.6 eV. Hereinafter, we consider intraband transitions only. The assumption kBT<< EF (kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature) allows us to disregard both interband transitions and temperature effects. The cubic conductivity is written in the local quasiclassical approximation as follows20,21

The nanoparticle polarizabilities are expressed as α2 = αSi = 6πε0ia1/k3 (a1 is the electric dipole Mie scattering coefficient) and

The size of the silicon nanoparticle was adjusted to avoid the appearance of Mie resonances in the infrared spectral range. In contrast50, the graphene-wrapped ZnSe nanoparticle possesses the pronounced resonance associated with the excitation of the dipole-type plasmon in the graphene shell. The eigenfrequency for this mode can be found from Eq. 7 and written in the linear and lossless case as follows

We adjusted the parameters of the structure to obtain ℏω0 = 0.133eV, which corresponds to the wavelength of a CO2 laser of 9.32 µm.

We estimate other parameters for this configuration as follows: ψ ≈ 550, γ ≈ 0.0082, δω/ω0 ≈ −7.4 × 10−6, ς ≈ −56, η ≈ −0.02.

References

Paar, C. & Pelzl, J. Understanding Cryptography. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010).

Ferguson, N., Schneier, B. & Kohno, T. Cryptography Engineering: Design Principles and Practical Applications. (Wiley, New York, 2010).

Della, G. C. & Engheta, N. Digital metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 13, 1115–1121 (2014).

Cui, T. J., Qi, M. Q., Wan, X., Zhao, J. & Cheng, Q. Coding metamaterials, digital metamaterials and programmable metamaterials. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e218 (2014).

Cui, T. J., Liu, S. & Li, L. L. Information entropy of coding metasurface. Light Sci. Appl. 5, e16172 (2016).

Cui, T. J., Liu, S. & Zhang, L. Information metamaterials and metasurfaces. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5, 3644–3668 (2017).

Silva, A. et al. Performing mathematical operations with metamaterials. Science 343, 160–163 (2014).

Li, L. L. et al. Electromagnetic reprogrammable coding-metasurface holograms. Nat. Commun. 8, 197 (2017).

Chen, J. W. et al. Tungsten disulfide–gold nanohole hybrid metasurfaces for nonlinear metalenses in the visible region. Nano. Lett. 18, 1344–1350 (2018).

Moccia, M. et al. Coding metasurfaces for diffuse scattering: scaling laws, bounds, and suboptimal design. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1700455 (2017).

Wu, H. T. et al. Controlling energy radiations of electromagnetic waves via frequency coding metamaterials. Adv. Sci. 4, 1700098 (2017).

Gibbs, H. M. Optical Bistability, Controling Light with Light. 133 (Academic, Orlando, 1985).

Rosanov, N. N. Spatial Hysteresis and Optical Patterns. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2002).

Liu, L. et al. An ultra-small, low-power, all-optical flip-flop memory on a silicon chip. Nat. Photonics 4, 182–187 (2010).

Li, Z. Y. & Meng, Z. M. Polystyrene Kerr nonlinear photonic crystals for building ultrafast optical switching and logic devices. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2, 783–800 (2014).

Ginzburg, P., Krasavin, A. V., Wurtz, G. A. & Zayats, A. V. Non-perturbative hydrodynamic model for multiple harmonics generation in metallic nanostructures. ACS Photonics 2, 8–13 (2015).

Krasavin, A. V., Ginzburg, P., Wurtz, G. A. & Zayats, A. V. Nonlocality-driven supercontinuum white light generation in plasmonic nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 7, 11497 (2016).

Chen, J. S. et al. Evidence of high-order nonlinearities in supercontinuum white-light generation from a gold nanofilm. ACS Photonics 5, 1927–1932 (2018).

Palpant, B. Third-order nonlinear optical response of metal nanoparticles. in Non-Linear Optical Properties of Matter (eds Papadopoulos, M. G., Sadlej, A. J., Leszczynski, J.) 461–508 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2006).

Mikhailov, S. A. & Ziegler, K. Nonlinear electromagnetic response of graphene: frequency multiplication and the self-consistent-field effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 384204 (2008).

Peres, N. M. R., Bludov, Y. V., Santos, J. E., Jauho, A. P. & Vasilevskiy, M. I. Optical bistability of graphene in the terahertz range. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125425 (2014).

Noskov, R. E., Belov, P. A. & Kivshar, Y. S. Subwavelength modulational instability and plasmon oscillons in nanoparticle arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 093901 (2012).

Balanis, C. A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design. (Wiley-Interscience, New York, 2005).

Shegai, T. et al. A bimetallic nanoantenna for directional colour routing. Nat. Commun. 2, 481 (2011).

Gan, X. T. et al. Graphene-controlled fiber bragg grating and enabled optical bistability. Opt. Lett. 41, 603–606 (2016).

Gu, T. et al. Regenerative oscillation and four-wave mixing in graphene optoelectronics. Nat. Photonics 6, 554–559 (2012).

Zhang, K., Huang, Y., Miroshnichenko, A. E. & Gao, L. Tunable optical bistability and tristability in nonlinear graphene-wrapped nanospheres. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 11804–11810 (2017).

Feurer, T., Vaughan, J. C. & Nelson, K. A. Spatiotemporal coherent control of lattice vibrational waves. Science 299, 374–377 (2003).

Brinks, D. et al. Visualizing and controlling vibrational wave packets of single molecules. Nature 465, 905–908 (2010).

Koehler, J. R., Noskov, R. E., Sukhorukov, A. A., Novoa, D. & Russell, PstJ. Coherent control of flexural vibrations in dual-nanoweb fibers using phase-modulated two-frequency light. Phys. Rev. A. 96, 063822 (2017).

Albrecht, G., Ubl, M., Kaiser, S., Giessen, H. & Hentschel, M. Comprehensive study of plasmonic materials in the visible and near-infrared: linear, refractory, and nonlinear optical properties. ACS Photonics 5, 1058–1067 (2018).

Drachev, V. P., Buin, A. K., Nakotte, H. & Shalaev, V. M. Size dependent χ(3) for conduction electrons in Ag nanoparticles. Nano. Lett. 4, 1535–1539 (2004).

Neuendorf, R., Quinten, M. & Kreibig, U. Optical bistability of small heterogeneous clusters. J. Chem. Phys. 104, 6348–6354 (1996).

Argyropoulos, C., Chen, P. Y., Monticone, F., D’Aguanno, G. & Alù, A. Nonlinear plasmonic cloaks to realize giant all-optical scattering switching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 263905 (2012).

Yu, W. J., Ma, P. J., Sun, H., Gao, L. & Noskov, R. E. Optical tristability and ultrafast fano switching in nonlinear magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 97, 075436 (2018).

Makarov, S. V. et al. Light-induced tuning and reconfiguration of nanophotonic structures. Laser Photon Rev. 11, 1700108 (2017).

Smirnova, D. A., Noskov, R. E., Smirnov, L. A. & Kivshar, Y. S. Dissipative plasmon solitons in graphene nanodisk arrays. Phys. Rev. B 91, 075409 (2015).

Noskov, R. E. & Zharov, A. A. Optical bistability of planar metal/dielectric nonlinear nanostructures. Opto-Electron. Rev. 14, 217–223 (2006).

Husakou, A. & Herrmann, J. Steplike transmission of light through a metal-dielectric multilayer structure due to an intensity-dependent sign of the effective dielectric constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 127402 (2007).

Yanik, M. F., Fan, S. H., Soljačić, M. & Joannopoulos, J. D. All-optical transistor action with bistable switching in a photonic crystal cross-waveguide geometry. Opt. Lett. 28, 2506–2508 (2003).

Amo, A. et al. Exciton–polariton spin switches. Nat. Photonics 4, 361–366 (2010).

Chen, R. et al. Nanophotonic integrated circuits from nanoresonators grown on silicon. Nat. Commun. 5, 4325 (2014).

Xomalis, A. et al. Fibre-optic metadevice for all-optical signal modulation based on coherent absorption. Nat. Commun. 9, 182 (2018).

Whitham, G. B. Linear and Nonlinear Waves. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999).

Gao, L. & Li, Z. Y. Self-consistent formalism for a strongly nonlinear composite: comparison with variational approach. Phys. Lett. A 219, 324–328 (1996).

Thongrattanasiri, S., Manjavacas, A., García & de Abajo, F. J. Quantum finite-size effects in graphene plasmons. ACS Nano 6, 1766–1775 (2012).

Olivares, I., Rojas, R. & Claro, F. Surface modes of a pair of unequal spheres. Phys. Rev. B 35, 2453–2455 (1987).

Chandler-Horowitz, D. & Amirtharaj, P. M. High-accuracy, midinfrared (450 cm−1 ≤ ω ≤ 4000 cm−1) refractive index values of silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 123526 (2005).

Connolly, J., diBenedetto, B. & Donadio, R. Specifications of raytran material. Proc. SPIE 0181, 141–144 (1979).

Christensen, T., Jauho, A. P., Wubs, M. & Mortensen, N. A. Localized plasmons in graphene-coated nanospheres. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125414 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by PAZY Foundation, Kamin Project, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11374223), the National Science of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20161210), the Qing Lan project, the “333” project (Grant No. BRA2015353), and PAPD of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and China Scholarship Council (CSC). REN acknowledges useful discussions with Prof. N. A. Gippius, M. V. Tsarev, I. I. Shishkin, and A. Machnev.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, P., Gao, L., Ginzburg, P. et al. Ultrafast cryptography with indefinitely switchable optical nanoantennas. Light Sci Appl 7, 77 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-018-0079-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-018-0079-9