Abstract

Chromosomal abnormalities are established prognostic markers in adult ALL. We assessed the prognostic impact of established chromosomal abnormalities and key copy number alterations (CNA) among 652 patients with B-cell precursor ALL treated on a modern MRD driven protocol. Patients with KMT2A-AFF1, complex karyotype (CK) and low hypodiploidy/near-triploidy (HoTr) had high relapse rates 50%, 60% & 53% and correspondingly poor survival. Patients with BCR-ABL1 had an outcome similar to other patients. JAK-STAT abnormalities (CRLF2, JAK2) occurred in 6% patients and were associated with a high relapse rate (56%). Patients with ABL-class fusions were rare (1%). A small group of patients with ZNF384 fusions (n = 12) had very good survival. CNA affecting IKZF1, CDKN2A/B, PAX5, BTG1, ETV6, EBF1, RB1 and PAR1 were assessed in 436 patients. None of the individual deletions or profiles were associated with survival, either in the cohort overall or within key subgroups. Collectively these data indicate that primary genetic abnormalities are stronger prognostic markers than secondary deletions. We propose a revised UKALL genetic risk classification based on key established chromosomal abnormalities: (1) very high risk: CK, HoTr or JAK-STAT abnormalities; (2) high risk: KMT2A fusions; (3) Tyrosine kinase activating: BCR-ABL1 and ABL-class fusions; (4) standard risk: all other patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outcome for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) treated with multi-agent chemotherapy remains unsatisfactory. Adoption of treatment elements from paediatric protocols, targeted therapy for specific subtypes, improved disease monitoring and better risk stratification have benefited some patient subgroups [1]. However, further advances are required especially for older adults for whom treatment intensification is not feasible due to toxicity [1]. Accurate stratification according to the risk of treatment failure is vital for effective patient management and improving outcome. A profusion of genomic studies over the past 10–15 years has identified numerous recurrent genetic abnormalities. The prognostic or predictive value of these potential biomarkers has yet to be fully determined in adult ALL.

The UKALLXII/ECOG2993 international trial generated one of the first widely used risk classifiers in adult ALL, showing that patients harbouring BCR-ABL1, KMT2A-AFF1, low hypodiploidy/near triploidy (HoTr), or complex karyotype (CK) had an inferior survival [2,3,4]. This study identified the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of induction and age >40 years as risk factors for poor outcome [5, 6]. These findings were applied in UKALL14 and patients with one or more of these risk features were assigned to the high-risk arm and allocated to allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) wherever possible [7].

Retrospective studies examining the prognostic impact of copy number alterations (CNA) or mutations have reported correlations with outcome but the magnitude of the effect was often marginal, frequently restricted to specific genetic subtypes and rarely replicated across independent cohorts [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Hence, the majority of stratification algorithms in adult ALL focus on primary chromosomal abnormalities rather than secondary CNA or mutations, although there are rare exceptions [11]. Genomic studies have identified and characterised large numbers of additional primary genetic abnormalities, including ABL-class fusions and abnormalities leading to deregulated JAK-STAT signalling, which underpin the BCR-ABL1-like gene expression signatures [19,20,21]. Initial studies suggested the frequency of BCR-ABL1-like ALL increased with age and was associated with a poor outcome [22,23,24,25,26]. Moreover, there are emerging data to suggest that patients with an ABL-class fusion benefit from targeted therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor [27,28,29].

In this study, we sought to assess the prognostic impact of the most relevant primary and secondary genetic abnormalities in a large cohort of patients aged 25–65 years with ALL treated on a single clinical trial, UKALL14.

Materials and methods

Full details of patients and methods are provided in the supplementary methods section. Briefly patients (25-65 years) were enroled onto UKALL14 (ISRCTN 66541317), a phase 3 clinical trial for patients with de novo ALL between 2010 and 2018. All patients provided written informed consent to trial treatment and correlative science studies. Patients underwent a two-phase induction followed by stratification to continuing chemotherapy or allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) based on risk assessment. Patients were assigned to high-risk treatment if they had any of the following features: BCR-ABL1, KMT2A-AFF1, HoTr, CK, WCC > 30 × 109/l, MRD post phase 2 induction and ≥41 years. High-risk patients were assigned to allo-SCT if they were fit and had an antigen-matched sibling or unrelated donor.

Cytogenetics, FISH, MLPA and SNP array analyses were performed on diagnostic bone marrow samples by regional NHS genetic laboratories or the Leukaemia Research Cytogenetics Group at Newcastle University as previously described [8, 30]. (Supplementary Methods, Fig. S1, Table S1/S2) Principal genetic abnormalities were defined as BCR-ABL1/t(9;22)(q34;q11), KMT2A-AFF1/t(4;11)(q21;q23), other KMT2A fusions (together referred to as KMT2A-r), HoTr (30–39/60–78 chromosomes), CK (≥5 chromosomal abnormalities), JAK-STAT abnormalities (CRLF2 or JAK2 fusions), ABL-class fusions (ABL1, ABL2, PDGFRB, CSF1R fusions, except BCR-ABL1), ETV6-RUNX1, high hyperdiploidy (51–65 chromosomes), ZNF384 fusions (ZNF384-r), and t(1;19)(q21;p13)/TCF3-PBX1. MRD analysis was preformed and interpreted by the UK Adult ALL MRD lab according to EuroMRD guidelines [31]. MRD was measured after both phases of induction but only the post-phase 2 results were used to assign treatment. Survival analysis focussed on event-free survival (EFS), relapse rate (RR) and overall survival (OS) at 3 years which were calculated using Kaplan–Meier methods (see supplementary methods). Hazard ratios were estimated using univariable and multivariable Cox regression models. All P values were two-sided and, because of multiple testing, values <0.01 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Intercooled Stata v16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R version 3.4.3 (http://www.R-project.org).

Results

Frequency and key clinical correlates of primary chromosomal abnormalities

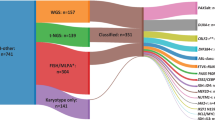

A total of 652 patients with B-cell precursor ALL were included in this study (Table 1, Fig. S1). The median age of the cohort was 46 years with an interquartile range of 35–55 years. BCR-ABL1 was the most prevalent abnormality (31%) followed by KMT2A-r and HoTr (10% each) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Overall, 319 (49%) patients’ disease harboured a pre-defined high-risk genetic abnormality (BCR-ABL1, KMT2A-AFF1, HoTr, CK). Most KMT2A-r cases had KMT2A-AFF1 (49/58, 84%) but other partner genes were observed: MLLT1 (n = 6) and MLLT4, EPS15, LASP1, unknown (one each). Conventional karyotype revealed a CK in 21 (4%) cases. None of the CK cases harboured BCR-ABL1, KMT2A-r or TCF3-PBX1 and the majority (>80%) were also negative for ABL-class, JAK-STAT and ZNF384-r.

A Pie chart showing the frequency of chromosomal abnormalities. Most KMT2A rearranged cases had KMT2A-AFF1 (i.e., t(4;11), 49/58, 84%) but other partner genes were observed: MLLT1 (n = 6) and MLLT4, EPS15, LASP1, unknown (one each). The low hypodiploidy (30–39 chromosomes) group included two cases of near-haploidy (26–28 chromosomes). The JAK-STAT group comprised IGH-CRLF2 (n = 23), P2RY8-CRLF2 (n = 9) and JAK2 fusions (n = 2, PAX5-JAK2 & BCR-JAK2). P2RY8-CRLF2 fusions were identified by MLPA (n = 4), FISH (n = 3) or both techniques (n = 2). We were able to identify the partner gene in 3/6 cases: EBF1-PDGFRB (n = 2), FOXP1-ABL1 (n = 1). The remaining three cases had a PDGFRB/CSF1R (n = 2) or ABL1 (n = 1) rearrangement. Twelve patients had a ZNF384 rearrangement with EP300 (n = 5) and TCF3 (n = 4) being the most prevalent partners along with single cases of AKAP8-ZNF384 and EWSR1-ZNF384 and one where the partner gene is unknown. B Bar chart and table showing the frequency and co-occurrence of copy number alterations.

A small majority of the 52 patients with ALL classified as HoTr (29/52, 56%) presented with direct evidence of a clone with <40 chromosomes. Analysis of the remaining 23 cases with a near-triploid clone [cytogenetics (n = 23), SNP array (n = 14)] revealed features consistent with the HoTr subgroup; i.e., tetrasomy of chromosome 1, 6, 11 and 19 and widespread whole chromosome copy-number neutral loss of heterozygosity (CNN-LOH) [30, 32]. Three cases with a near-triploid clone and CNN-LOH had a modal chromosome number below the standard threshold of 60 chromosomes; the presence of a TP53 mutation in all three cases confirmed their HoTr status [30]. There was no difference in the demographics or clinical features of patients with HoTr according to type of clone(s) present at diagnosis (Table S3).

The two major genetic subgroups underlying the BCR-ABL1-like/Philadelphia-like gene expression profile are defined by JAK-STAT abnormalities and ABL-class fusions. FISH and MLPA screening of >500 cases revealed a frequency of 6% and 1% respectively (Table 1, Fig. 1, Fig. S1). The JAK-STAT group comprised IGH-CRLF2 (n = 23), P2RY8-CRLF2 (n = 9) and JAK2 fusions (n = 2, PAX5-JAK2 & BCR-JAK2). P2RY8-CRLF2 fusions were determined by MLPA (n = 4), FISH (n = 3) or both (n = 2). We were able to identify the partner gene in 3/6 cases: EBF1-PDGFRB (n = 2), FOXP1-ABL1 (n = 1). The remaining three cases had a PDGFRB or /CSF1R fusion (n = 2) or ABL1 (n = 1) rearrangement. A lack of material prevented the identification of the partner gene.

A total of 14 (3%) patients had ALL with TCF3-PBX1 detected by karyotyping (n = 10) and/or FISH analysis (n = 10). Karyotyping, FISH and SNP array analysis revealed the unbalanced form of the translocation [der(19)t(1;19)] in 8/14 (57%) cases. Patients with der(19)t(1;19) harbour two normal copies of chromosome 1 and thus have trisomy of chromosome arm 1q (Fig. S2c). SNP array analysis of these 14 patient specimens plus an additional 9 t(1;19) cases from UKALLXII [2] showed that all patients with der(19)t(1;19) harboured heterodisomy of chromosome 1 rather than uniparental disomy of chromosome 1 (Fig. S2a, b); suggesting the translocation arose during the G2 phase of the cell cycle rather following after duplication of a normal copy of chromosome 1 [33]. Comparing the demographics and clinical features of patients with the balanced and unbalanced form of the t(1;19) revealed no significant differences.

Twelve patient samples had a ZNF384-r with EP300 (n = 5) and TCF3 (n = 4) being the most prevalent partners along with single cases of AKAP8-ZNF384 and EWSR1-ZNF384 and one where the partner gene is unknown.

Chromosomal abnormalities associated with childhood ALL were rare: iAMP21 (n = 4), ETV6-RUNX1 (n = 1), and patients were younger (25, 26, 26, 30 and 48 years). There were few strong correlations between genetic abnormalities and demographic features but HeH and ZNF384-r were more common in patients ≤40 years old whereas HoTr was more prevalent among patients >40 years (Table 1). In addition, patients with HeH or HoTr had lower WCC, but patients with KMT2A-r had elevated WCC.

Frequency of copy number alterations and correlation with primary chromosomal abnormalities

CNA affecting IKZF1, CDKN2A/B, PAX5, BTG1, ETV6, EBF1, RB1 and the PAR1 region were determined by MLPA in a representative cohort of 437 patients (Table S2). One or more CNA was observed in 270 (62%) patients. Deletions of IKZF1 or CDKN2A/B occurred in 39% and 37% cases (Table 2, Fig. 1B). PAX5 alterations and BTG1 deletions were present in 21% and 11% cases while other deletions were present in <10% cases. A total of 189 IKZF1 deletions were detected in 170 patients. MLPA detects the full spectrum of deletions ranging from canonical intragenic ex4-7 deletions to whole gene deletions as well as rare deletions (Fig. S3). Among 162 patients with a CDKN2A/B deletion, 95 (59%) were monoallelic and 67 (41%) biallelic. The distribution of deletions was not random and pairwise testing revealed numerous genes were co-deleted more often than expected (Fig. 1B). IKZF1 deletions frequently co-existed with CDKN2A/B deletions (p < 0.001). CDKN2A/B and PAX5 which are co-located on chromosome 9p were also frequently co-deleted (p < 0.001). Ninety-three patients (57% of those with an IKZF1 deletion) fulfilled the criteria for IKZF1plus [IKZF1 deletion plus PAX5, CDKN2A/B or PAR1 deletion] [34]. There was no association between the type of CDKN2A/B deletion and deletion of the other genes investigated (Fig. S4b).

There was a strong correlation between primary genetic subtype and the spectrum of CNA (Figs. 2 and 3). Patients with BCR-ABL1 had a higher frequency of IKZF1 deletions and IKZF1plus compared to other cases: 60% v 22%, p < 0.01 and 32% v 16%, p < 0.01. Patients with KMT2A-r had few recurrent deletions and 26 (56%) harboured none of these deletions. The only CNA present in >3 KMT2A-r cases was CDKN2A/B deletions in 17/46 (37%) cases. Patients with a JAK-STAT abnormality had a higher frequency of all CNA (Fig. 3); especially IKZF1 deletions and IKZF1plus 63% v 18%, p < 0.01 and 54% v 12%, p < 0.01 respectively. Patients with a CK harboured a high frequency of CDKN2A/B and/or PAX5 deletions (10/14, 71%) but few IKZF1 deletions (3/14). In order to investigate the spectrum of CNAs associated with CK in more detail, we performed SNP array analysis on a cohort of CK cases from UKALL14 (n = 9) and UKALLXII (n = 10). This genome-wide analysis confirmed the high frequency of CDKN2A/B deletions and low frequency of IKZF1 deletions (Fig. S5a). There was no consistent pattern or profile of CNAs underpinning CK. The most frequently deleted regions were 9p and 6q targeting CDKN2A/B, MTAP, BACH2 and EPHA7 (Fig. S5c). There were few correlations between CNA and demographic or clinical features (Table 2). The exception was a female predominance among patients with an ETV6 deletion (21 females: 12 males, p = 0.018).

Oncoplot showing the pattern of individual copy number alterations, IKZF1plus profile and the UKALL-CNA profile per case according genetic subtype. Purple cells indicate the presence of a deletion affecting that gene. Notes: (1) Patients with low hypodiploidy were under-represented in the tested cohort due to a high failure rate. Calling copy number alterations by MLPA on a backdrop of large-scale chromosomal loss and ploidy doubling is a recognised limitation of the assay (Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 2010, 49:1104); (2) PAX5 alterations included a single case with an intragenic PAX5 amplification (Blood Advances 2017, 1:1473); (3) Among 170 cases with an IKZF1 deletion, 93 were classified as fulfilling the definition of IKZF1plus (IKZF1 deletion with concomitant CDKN2A/B, PAX5 or PAR1 deletion in the absence of an ERG deletion). All 93 cases had IKZF1 deletion with concomitant CDKN2A/B, PAX5 or PAR1 deletion. Among these cases, 68 cases with an established primary genetic abnormality were assumed to lack an ERG deletion as they are extremely rare in the absence of IGH-DUX4. A further 18 cases tested negative for an ERG deletion by MLPA. The remaining 7 cases, who were not tested due to lack of material, were included on the basis that ERGdeletions are rare in B-other (4/150, <3%) and hence <1 case is likely be incorrectly classified.

Outcome of patients by genetic subtype and prognostic impact of secondary abnormalities

After a median follow-up time of 4.45 years, the 3-year survival rates for the whole BCP-ALL cohort were OS 54% (95% CI 50–58%), EFS 47% (43–51%), RR 32% (28–37%) (Table 1). In univariable analysis, patients with HoTr or CK had double the rate of relapse and death compared with other patients. The OS rates were 22% (11–34%) and 24% (9–43%) respectively despite being treated as high risk and in the case of HoTr having a relatively good response to induction therapy (Table 1). Patients with KMT2A-AFF1 had an increased RR but not a worse OS. There was no difference in outcome for patients with HoTr according to the ploidy of the presenting clone. However, there was some suggestion that patients presenting with low hypodiploid clones had lower CR rates and higher non-relapse mortality (Table S3).

Patients with BCR-ABL1 did not have a higher RR or poorer OS compared to the remaining patients (hazard ratio 0.89 (95% CI 0.65–1.22), p = 0.5 and 0.89 (0.69–1.13), p = 0.3, respectively). Among patients with abnormalities underpinning BCR-ABL1-like, the 6 patients with an ABL-class fusion did not have a poor outcome—all achieved a complete remission post phase 2 and none relapsed within three years of diagnosis. The ABL-class fusion was identified retrospectively so did not influence therapy. MRD was evaluated for four patients and three were negative. In contrast, the 35 patients with a JAK-STAT abnormality had a high rate of MRD positivity at both time-points (88% & 76%), high RR (56%) and a poor OS (36%) despite 83% being treated as high-risk (Table 1).

Patients with TCF3-PBX1 had outcome almost identical to the cohort overall with RR and OS rates of 38% and 54% respectively. The RR among patients with the balanced and unbalanced form of the translocation was very similar (40% v 38%). Although the ZNF384 subgroup was small (n = 12) none suffered an event within 3 years of diagnosis. Two patients relapsed after 3 years, one at 3.1 years and one at 6.3 years and both died within a year of relapse.

Overall none of the CNA detected by MLPA were associated with survival (Table 2). As previously reported, IKZF1 deletions did not confer an inferior outcome in BCR-ABL1 positive, BCR-ABL1 negative or B-other ALL (Table S4) [35]. Extending our analysis to examine the type of deletion (exons 4–7 and whole gene) and IKZF1plus, again did not reveal any association with outcome (Table S4). Patients harbouring P2RY8-CRLF2 had a high RR consistent with the outcome of the broader JAK-STAT subgroup (Table 1). We found no evidence of a prognostic effect associated with the UKALL-CNA profile [36, 37] in the whole cohort or the B-other subgroup (Table S4). However the presence of a biallelic CDKN2A/B deletion was associated with a poor outcome in the BCR-ABL1 cohort but not the remaining cases (Table S4, Fig. S4c, d). A comparison of the outcome of patients with biallelic and monoallelic deletions and BCR-ABL1 revealed raised, but not significant, hazard ratios (Table S4). However, the presence of a biallelic CDKN2A/B deletion was associated with lower EFS and OS rates when compared with patients with no CDKN2A/B deletion but not higher RR (EFS hazard ratio 1.93 (1.14–3.24), p = 0.01 and OS 1.88 (1.06–3.35), p = 0.03). A multivariate EFS model with variables for CDKN2A\B and BCR-ABL1 status revealed significant interaction indicating that the prognostic effect of biallelic CDKN2A/B deletion was different in BCR-ABL1 positive and negative cases (p = 0.046).

Revised genetic risk classification for adult ALL

We propose a revised genetic classification for adult ALL comprising five subgroups with distinct genetics and/or outcomes (Table 3, Fig. 4). The very high-risk (VHR) category includes patients with HoTr and CK who had an OS rates <25% at 3 years despite being classified and treated as high risk. Patients with JAK-STAT abnormalities are also included in the VHR group on the basis of a high RR and MRD rates. Stratifying the VHR group according to MRD status post phase 2 induction revealed a high RR at 3 years for both MRD negative and MRD positive cases: 54% (35–76) and 81% (59–95) hazard ratio 1.79 (0.85–3.79), p = 0.126. The high-risk group comprises all patients with a KMT2A fusion. Although only KMT2A-AFF1 was classified as high risk on UKALL14, 50% of patients with other KMT2A fusion partners relapsed. KMT2A-r were not grouped in the VHR group because their OS rates were >40%. Patients in the HR group (i.e. KMT2A-r) had a differential RR at 3 years according to MRD status: MRD positive 69% (46-89) v MRD negative 9% (1–49); hazard ratio 6.80 (95% CI 1.49-30.92), p = 0.013. Patients with BCR-ABL1 and ABL-class fusion were combined on the basis of the underlying functional consequence of the fusions and likely sensitivity to a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The remaining cases which encompass B-other ALL and abnormalities associated with paediatric ALL/younger age are categorised together in standard risk. The majority of patients in the new standard risk group were MRD negative post-induction (74/103, 72%). Among patients in the standard risk group there was no significant difference in RR at 3 years between patients who were MRD positive and negative: 34% (18–57) v 21% (13–32), hazard ratio 1.56 (0.72–3.40), p = 0.263. In comparison with the standard genetic risk group, patients in the high-risk genetic group had inferior outcomes in univariable but not in multivariable analysis (Table 3). Whereas the inferior outcome of patients with very high-risk genetics was independent of sex, age and WCC. Patients with tyrosine kinase activating fusions had significantly decreased EFS but not increased RR in relation to standard risk patients. The small number of patients in each revised genetic group receiving protocol defined post-induction therapy makes estimating the interaction between genetics and treatment difficult especially as several genetic abnormalities were used to assign patients to high-risk therapy (Table 3). The OS of patients in the new standard risk genetic group was 64% (57–71) at 3 years significantly higher than other patients 47% (41–52), hazard ratio 1.65 (1.27–2.12), p < 0.001. One third of these patients (n = 62) received chemotherapy maintenance per protocol and achieved a 3 years OS rate of 72% (57–82).

Discussion

The central aims of this project were (1) to assess the prognostic impact of key genetic abnormalities in a contemporary MRD driven trial (UKALL14) and (2) to revise the UKALL genetic risk classification system for adult ALL. We have assessed the prognostic impact of a wide range of genetic abnormalities and propose a revised genetic classification of adult ALL BCP-ALL (Fig. 4). The four risk groups can be used to evaluate the efficacy of treatment interventions including transplant as well as providing a basis for designing novel risk stratification algorithms. Evaluating this revised classification system in additional datasets will help determine its relevance in the context of other therapies; especially immunotherapies.

Patients in UKALL14 with HoTr, KMT2A-AFF1 or CK were assigned high risk therapy irrespective of other clinical features or MRD. Despite this intervention, the survival of patients with HoTr or CK remained below 25% at 3 years. The poor outcome associated with HoTr has been reported by both paediatric and adult ALL study groups and given the high frequency of TP53 mutations in HoTr is perhaps not surprising [26, 32, 38,39,40]. HoTr can cause diagnostic dilemmas because patients present with one or two of the related clones and when only a near-triploid clone is detected there can be confusion with HeH [30]. We recently published guidance and an algorithm to assist in the diagnosis of HoTr in these scenarios [30].

The association of CK with poor outcome has not been observed universally.(37, 41) This outcome heterogeneity is likely due to the subjective nature of the definition of CK. We screened CK cases for known gene fusions but found only one. SNP array analysis of CK cases did not find a consistent or novel profile of CNA underpinning this subgroup. The poor outcome cannot be attributed to IKZF1 deletions or IKZF1plus which are rare in this subgroup (Fig. 2B). The most frequent CNA observed in CK was CDKN2A/B deletions but these are common across all BCP-ALL and not associated with outcome unless present as biallelic deletions which were not common in CK. Further genomic studies are urgently needed to unravel the key genetic drivers of this subtype.

The outcome of patients with KMT2A-AFF1 and other KMT2A-r was very similar which was not the case in UKALLXII [2]. Compared with age-matched counterparts from UKALLXII, patients with KMT2A-AFF1 treated on UKALL14 had similar RR rates (~50%) but a higher OS rates (45% v < 35%) [4]. It is difficult to compare outcomes across different treatment eras but in UKALL14 patients with KMT2A-AFF1 were recommended for allo-SCT which was not the case in UKALLXII.

Patients on UKALL14 with BCR-ABL1 were treated with imatinib added and asparaginase omitted and had an outcome very similar to the overall cohort (Table 1). Although IKZF1 deletions and IKZF1plus were prevalent in this subgroup those lesions did not have any prognostic effect. A previous GMALL study also showed no effect of IKZF1 deletions but did report an adverse effect of CDKNA2/B deletions in patients undergoing allo-SCT [12]. We did not observe any prognostic effect of CDKN2A/B deletions per se but did notice a trend towards an adverse effect for BCR-ABL1 patients with biallelic CDKN2A/B deletions which was not restricted to patients receiving an allo-SCT. There were several key differences between the two studies. The GMALL study was smaller (n = 97) recruited patients as young as 18 years old and comprised three different imatinib schedules including “late” imatinib which we have previously shown to be less effective in the UKALLXII trial [41].

We examined the outcome of patients with the two primary genetic drivers of the BCR-ABL1-like subtype. Patients with JAK-STAT abnormalities had a high RR (56% at 3 years) akin to patients with HoTr or CK. Although these patients were not assigned high risk therapy on the basis of genetics, the majority (>80%) received high risk therapy due to other reasons, notably MRD. JAK-STAT abnormalities account for a significant proportion of the BCR-ABL1-like subtype so our results are consistent with previous reports [22,23,24,25,26]. The frequency of ABL-class fusions in this study was low (1%) but consistent with that reported by a US study (2%)[22]. It is impossible to draw definitive conclusions regarding outcome on such a small subgroup but their outcome did not appear to be poor.

TCF3-PBX1 has previously been reported to be associated with a poor outcome and some clinical study groups classify and treat patients as high risk [40, 42, 43]. However in UKALL14, these patients had an OS rate identical to the whole BCP-ALL cohort (54%) a result consistent with our UKALLXII study [2]. We also report that our small group of 12 patients with ZNF384-r had a relatively good outcome with only 2 relapses/deaths reported to date. This finding is consistent with a larger cohort of patients with ZNF384-r treated in Japan who had a 5 year OS rate of 74% [44].

We assessed the frequency and prognostic impact of common CNA in adult ALL. The frequency and distribution of the CNA studied in this report were consistent with our previous UKALLXII study [8] and those from other study groups [9, 11,12,13,14]. With the exception of a trend for biallelic deletions of CDKN2A/B in BCR-ABL1 cases, we failed to identify any significant associations between CNA and outcome. This was true for individual deletions and CNA profiles in both the whole cohort and specific subgroups. This finding is in contrast to other studies which reported prognostic associations for several CNA notably IKZF1 and CDKN2A/B deletions [8, 9, 11, 13, 14]. The majority of these studies used MLPA as the primary or validation technique so it is unlikely that diverse methodologies are driving these differences. This is supported by the fact that we did not observe any prognostic effect of IKZF1 deletions in UKALL14 using PCR [35]. However, there are major differences between UKALL14 and other studies with respect to cohort size, age range of the patients and use of SCT. We examined the prognostic effect of CNA among 436 patients aged 25–65 years including 163 patients who were BCR-ABL1 positive. Previous studies were significantly smaller (mostly < 300 patients) and included younger patients (15–24 years) [8, 9, 11,12,13,14]. As the incidence of ALL decreases sharply between 15 and 24 years of age [45] many of the previous cohorts includes large number of cases not eligible for UKALL14. For example, 40% of patients included in our previous UKALLXII study were aged under 25 years old [8]. This point, coupled with the small size of the previous studies and the low frequency of some CNA deletions, means that previous studies were ill-equipped to assess the prognostic impact of CNA in adults aged >25 years old. Our previous UKALLXII study included 51 patients with an IKZF1 deletion >25 years old much lower than the 170 patients in this study. In addition, the CNA examined in this study and previous studies are based on deletions common in high-risk children (43) and may not represent the key CNA in adult ALL. Our findings are substantially more robust and pertinent to the wider group of adults with ALL. This is an important observation given that many adolescent and young adult patients are increasingly being treated on paediatric inspired protocols and future adult ALL protocols are likely to have age inclusion criteria more akin to UKALL14.

In conclusion, the extensive analysis of genetic data for adults treated on UKALL14 confirmed the high-risk status of HoTr, KMT2A-r and CK while adding JAK-STAT abnormalities to the list of high-risk abnormalities in adult ALL. We have proposed a revised UKALL genetic classification for adult ALL which will enhance future studies.

References

Bassan R, Bourquin JP, DeAngelo DJ, Chiaretti S. New approaches to the management of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2018: JCO2017773648.

Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, Richards SM, Secker-Walker LM, Martineau M, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 Trial. Blood. 2007;109:3189–97.

Fielding AK, Rowe JM, Richards SM, Buck G, Moorman AV, Durrant IJ, et al. Prospective outcome data on 267 unselected adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia confirms superiority of allogeneic transplantation over chemotherapy in the pre-imatinib era: results from the International ALL Trial MRC UKALLXII/ECOG2993. Blood. 2009;113:4489–96. May 07.

Marks DI, Moorman AV, Chilton L, Paietta E, Enshaie A, DeWald G, et al. The clinical characteristics, therapy and outcome of 85 adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and t(4;11)(q21;q23)/MLL-AFF1 prospectively treated in the UKALLXII/ECOG2993 trial. Haematologica. 2013;98:945–52. Jun.

Patel B, Rai L, Buck G, Richards SM, Mortuza Y, Mitchell W, et al. Minimal residual disease is a significant predictor of treatment failure in non T-lineage adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: final results of the international trial UKALL XII/ECOG2993. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:80–9. Jan.

Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, Tallman MS, Buck G, Fielding AK, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008;111:1827–33. Feb 15.

Patel B, Kirkwood AA, Dey A, Marks DI, McMillan AK, Menne TF, et al. Pegylated-asparaginase during induction therapy for adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: toxicity data from the UKALL14 trial. Leukemia. 2017;31:58–64.

Moorman AV, Schwab C, Ensor HM, Russell LJ, Morrison H, Jones L, et al. IGH@ translocations, CRLF2 deregulation, and microdeletions in adolescents and adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3100–8.

Ribera J, Morgades M, Zamora L, Montesinos P, Gomez-Segui I, Pratcorona M, et al. Prognostic significance of copy number alterations in adolescent and adult patients with precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia enrolled in PETHEMA protocols. Cancer. 2015;121:3809–17.

Safavi S, Hansson M, Karlsson K, Biloglav A, Johansson B, Paulsson K. Novel gene targets detected by genomic profiling in a consecutive series of 126 adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100:55–61.

Beldjord K, Chevret S, Asnafi V, Huguet F, Boulland ML, Leguay T, et al. Oncogenetics and minimal residual disease are independent outcome predictors in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:3739–49.

Pfeifer H, Raum K, Markovic S, Nowak V, Fey S, Oblander J, et al. Genomic CDKN2A/2B deletions in adult Ph(+) ALL are adverse despite allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2018;131:1464–75.

Messina M, Chiaretti S, Fedullo AL, Piciocchi A, Puzzolo MC, Lauretti A, et al. Clinical significance of recurrent copy number aberrations in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia without recurrent fusion genes across age cohorts. Br J Haematol. 2017;178:583–7.

Fedullo AL, Messina M, Elia L, Piciocchi A, Gianfelici V, Lauretti A, et al. Prognostic implications of additional genomic lesions in adult Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104:312–8.

Mansour MR, Sulis ML, Duke V, Foroni L, Jenkinson S, Koo K, et al. Prognostic implications of NOTCH1 and FBXW7 mutations in adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia on the MRC UKALLXII/ECOG E2993 protocol. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4352–6.

Trinquand A, Tanguy-Schmidt A, Ben Abdelali R, Lambert J, Beldjord K, Lengline E, et al. Toward a NOTCH1/FBXW7/RAS/PTEN-based oncogenetic risk classification of adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Group for Research in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4333–42.

Petit A, Trinquand A, Chevret S, Ballerini P, Cayuela JM, Grardel N, et al. Oncogenetic mutations combined with MRD improve outcome prediction in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2018;131:289–300.

Jenkinson S, Kirkwood AA, Goulden N, Vora A, Linch DC, Gale RE. Impact of PTEN abnormalities on outcome in pediatric patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on the MRC UKALL2003 trial. Leukemia. 2016;30:39–47.

Li JF, Dai YT, Lilljebjorn H, Shen SH, Cui BW, Bai L, et al. Transcriptional landscape of B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia based on an international study of 1,223 cases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E11711–E11720.

Gu Z, Churchman ML, Roberts KG, Moore I, Zhou X, Nakitandwe J, et al. PAX5-driven subtypes of B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2019;51:296–307.

Lilljebjorn H, Fioretos T. New oncogenic subtypes in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:1395–401.

Roberts KG, Gu Z, Payne-Turner D, McCastlain K, Harvey RC, Chen IM, et al. High frequency and poor outcome of Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:394–401.

Jain N, Roberts KG, Jabbour E, Patel K, Eterovic AK, Chen K, et al. Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a high-risk subtype in adults. Blood. 2017;129:572–81.

Tasian SK, Hurtz C, Wertheim GB, Bailey NG, Lim MS, Harvey RC, et al. High incidence of Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in older adults with B-ALL. Leukemia. 2017;31:981–4.

Chiaretti S, Messina M, Della Starza I, Piciocchi A, Cafforio L, Cavalli M, et al. Philadelphia-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with minimal residual disease persistence and poor outcome. First report of the minimal residual disease-oriented GIMEMA LAL1913. Haematologica. 2021;106:1559–68.

Paietta E, Roberts KG, Wang V, Gu Z, Buck G, Pei D, et al. Molecular Classification Improves Risk Assessment in Adult BCR-ABL1-negative B-ALL. Blood. 2021;138:948–58.

Tanasi I, Ba I, Sirvent N, Braun T, Cuccuini W, Ballerini P, et al. Efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia harboring ABL-class rearrangements. Blood. 2019;134:1351–5.

Cario G, Leoni V, Conter V, Attarbaschi A, Zaliova M, Sramkova L, et al. Relapses and treatment-related events contributed equally to poor prognosis in children with ABL-class fusion positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated according to AIEOP-BFM protocols. Haematologica. 2020;105:1887–94.

Moorman AV, Schwab C, Winterman E, Hancock J, Castleton A, Cummins M, et al. Adjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy improves outcome for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia who have an ABL-class fusion. Br J Haematol. 2020;191:844–51.

Creasey T, Enshaei A, Nebral K, Schwab C, Watts K, Cuthbert G, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism array-based signature of low hypodiploidy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2021;60:604–15.

Bruggemann M, Schrauder A, Raff T, Pfeifer H, Dworzak M, Ottmann OG, et al. Standardized MRD quantification in European ALL trials: proceedings of the Second International Symposium on MRD assessment in Kiel, Germany, 18-20 September 2008. Leukemia. 2010;24:521–35.

Charrin C, Thomas X, Ffrench M, Le QH, Andrieux J, Mozziconacci MJ, et al. A report from the LALA-94 and LALA-SA groups on hypodiploidy with 30 to 39 chromosomes and near-triploidy: 2 possible expressions of a sole entity conferring poor prognosis in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Blood. 2004;104:2444–51.

Paulsson K, Horvat A, Fioretos T, Mitelman F, Johansson B. Formation of der(19)t(1;19)(q23;p13) in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:144–8.

Stanulla M, Dagdan E, Zaliova M, Moricke A, Palmi C, Cazzaniga G, et al. IKZF1(plus) defines a new minimal residual disease-dependent very-poor prognostic profile in pediatric b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1240–9.

Mitchell RJ, Kirkwood AA, Barretta E, Clifton-Hadley L, Lawrie E, Lee S, et al. IKZF1 alterations are not associated with outcome in 498 adults with B-precursor ALL enrolled on the UKALL14 trial. Blood Adv. 2021;5:3322–32.

Hamadeh L, Enshaei A, Schwab C, Alonso CN, Attarbaschi A, Barbany G, et al. Validation of the United Kingdom copy-number alteration classifier in 3239 children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood Adv. 2019;3:148–57.

Moorman AV, Enshaei A, Schwab C, Wade R, Chilton L, Elliott A, et al. A novel integrated cytogenetic and genomic classification refines risk stratification in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:1434–44.

Holmfeldt L, Wei L, Diaz-Flores E, Walsh M, Zhang J, Ding L, et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:242–52.

Pui CH, Rebora P, Schrappe M, Attarbaschi A, Baruchel A, Basso G, et al. Outcome of children with hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective multinational study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:770–9.

Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Baranger L, Hunault M, Cuccuini W, Lefebvre C, Bidet A, et al. Impact of cytogenetic abnormalities in adults with Ph-negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:1832–44.

Fielding AK, Rowe JM, Buck G, Foroni L, Gerrard G, Litzow MR, et al. UKALLXII/ECOG2993: addition of imatinib to a standard treatment regimen enhances long-term outcomes in Philadelphia positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:843–50.

GFCH. Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic findings and outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. Blood. 1996;87:3135–42.

Mancini M, Scappaticci D, Cimino G, Nanni M, Derme V, Elia L, et al. A comprehensive genetic classification of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of the GIMEMA 0496 protocol. Blood. 2005;105:3434–41.

Yasuda T, Nishijima D, Kojima S, Kawazu M, Ueno T, Tsuzuki S, et al. Genomic and clinical characterization of adult Ph-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132:2821.

Dores GM, Devesa SS, Curtis RE, Linet MS, Morton LM. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001–2007. Blood. 2012;119:34–43.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating sites, local investigators and research teams for their ongoing participation in the study, together with patients who took part in this trial as well as their families. We acknowledge the input of all the scientists and technicians working in the adult ALL MRD laboratory based at UCL. The UKALL14 trial was coordinated by the CRUK & UCL Cancer Trials Centre and funded by CRUK (C27995/A9609, Fielding). This study was supported by research grants from Cancer Research UK (A21019, Moorman and Fielding) and Blood Cancer UK (15036, Moorman and Harrison). Finally, we thank the member laboratories of the UK Cancer Cytogenetic Group for cytogenetic data and material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and Design: AVM, AKF. Collection and assembly of data: AVM, EB, EJW, KT, AAK, AE, CS, TC, DL, EP, PP, LC-H. Data analysis and interpretation: AVM, EB, EB, EJW, KT, AAK, AE, AKF. Financial support: AVM, CJH, AKF. Administrative support: CJH, AVM. Provision of study materials or patients: AAK, DL, EP, PP, LC-H, BP, TM, AM, CR, DM, AKF. Manuscript writing: AVM. Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moorman, A.V., Barretta, E., Butler, E.R. et al. Prognostic impact of chromosomal abnormalities and copy number alterations in adult B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a UKALL14 study. Leukemia 36, 625–636 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01448-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01448-2

This article is cited by

-

The evolution of acute lymphoblastic leukemia research and therapy at MD Anderson over four decades

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2023)

-

Results of salvage therapy with mini-hyper-CVD and inotuzumab ozogamicin with or without blinatumomab in pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2023)

-

Cytogenetics or MRD in B-cell ALL. Do both reign supreme?

Leukemia (2022)

-

Molekulare Diversität der akuten lymphoblastischen Leukämie

Die Onkologie (2022)