Abstract

JAK2 unmutated or non-polycythemia vera (PV) erythrocytosis encompasses both hereditary and acquired conditions. A systematic diagnostic approach begins with documentation of historical hematocrit (Hct)/hemoglobin (Hgb) measurements and classification of the process as life-long/unknown duration or acquired. Further investigation in both categories is facilitated by determination of serum erythropoietin level (EPO). Workup for hereditary/congenital erythrocytosis requires documentation of family history and laboratory screening for high-oxygen affinity hemoglobin variants, 2, 3 biphosphoglycerate deficiency, and germline mutations that are known to alter cellular oxygen sensing (e.g., PHD2, HIF2A, VHL) or EPO signaling (e.g., EPOR mutations); the latter is uniquely associated with subnormal EPO. Acquired erythrocytosis is often elicited by central or peripheral hypoxia resulting from cardiopulmonary disease/high-altitude dwelling or renal artery stenosis, respectively; EPO in the former instance is often normal (compensated by negative feed-back). Other conditions associated with acquired erythrocytosis include EPO-producing tumors and the use of drugs that promote erythropoiesis (e.g., testosterone, erythropoiesis stimulating agents). “Idiopathic erythrocytosis” loosely refers to an otherwise not explained situation. Historically, management of non-PV erythrocytosis has been conflicted by unfounded concerns regarding thrombosis risk, stemming from limited phenotypic characterization, save for Chuvash polycythemia, well-known for its thrombotic tendency. In general, cytoreductive therapy should be avoided and phlebotomy is seldom warranted where frequency is determined by symptom control rather than Hct threshold. Although not supported by hard evidence, cardiovascular risk optimization and low-dose aspirin use are often advised. Application of modern genetic tests and development of controlled therapeutic intervention trials are needed to advance current clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Erythrocytosis refers to either a true or apparent increase in hemoglobin (Hgb)/hematocrit (Hct); distinction requires familiarity with sex-, race- and altitude-adjusted normal values, together with an appreciation of extreme normal values that exceed the 95th percentile (2 SD) of reference range and attention to clinical factors associated with plasma volume depletion (relative erythrocytosis) [1, 2]. In 2008, the World Health organization (WHO) proposed Hgb and Hct diagnostic thresholds of 18.5 g/dl/52% and 16.5 g/dl/48% in Caucasian males and females, respectively, for investigation of polycythemia vera (PV) [3]. However, in 2016, the WHO classification system revised the Hct/Hct thresholds for PV diagnosis to 16.5 g/dL/49% in males and 16 g/dL/48% in females [4]. In a recent large population-based study, the incidence of erythrocytosis ranged from 0.3% to 3.4% based on the application of the WHO 2008 and 2016 criteria, respectively; importantly increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality was reported only in the context of a higher Hgb threshold (WHO 2008) [3, 5].

The diagnostic workup of JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis lacks uniformity, and often includes investigations for rare hereditary conditions and several acquired entities known to be associated with secondary erythrocytosis [6]. In a substantial proportion (up to 70%) of patients, despite extensive testing, erythrocytosis remains uncharacterized and sometimes labeled as “idiopathic”, which is often a diagnosis of exclusion [7,8,9]. The complexity and variability of the decision-making processes involved in managing erythrocytosis were underscored by an international survey of 134 myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) physicians evaluating standard practice in erythrocytosis [10]; in this regard, while first-line assessments were relatively consistent (JAK2, EPO testing), second-line investigations were markedly heterogeneous. Equally variable were treatment practices, including the decision to initiate daily aspirin therapy and/or phlebotomy, as well as the desired Hct target, ranging from 48–56%. Some of this variability in management stems from unsubstantiated concern regarding thrombosis risk. The particular issue was further highlighted in a recent retrospective study where as many as one-third of patients with secondary erythrocytosis were subjected to bone marrow examination and 42% to periodic phlebotomy [11]. Herein, we outline our systematic diagnostic and therapeutic approach in JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis; our review also includes illustrative cases and a discussion on underlying pathogenetic mechanisms.

Illustrative cases

Case 1: Erythropoietin receptor (EPOR) mutation

A 48-year-old Caucasian lady, an elementary school teacher from Minnesota, was noted to have erythrocytosis while undergoing a kidney donor evaluation. Hgb and Hct were 19.4 g/dl and 57%, respectively, with normal leukocyte and platelet count. The patient had a history of persistent erythrocytosis with Hgb/Hct of 19.3 g/dl/58%, documented two decades prior to her diagnosis. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, optimally controlled with lisinopril; tobacco use, vascular events, or microvascular symptoms were absent in her medical history. Importantly, both her mother and brother were previously noted to have erythrocytosis. Initial laboratory evaluation included EPO (1.1 mIU/mL; normal reference range 2.6–18.5) and peripheral blood JAK2 mutational screen (wild-type for both exons 12 and 14). Based on family history and subnormal EPO, EPOR mutation screen was pursued and revealed a heterozygous c.1316G>A, p.(Trp439*) mutation in exon 8 that caused a premature stop codon and truncated the 70 C-terminal amino acids resulting in a gain of function [12]; the altered C-terminal increases EPOR stability at the cell surface resulting in pre-activation of both receptor and constitutive JAK2 signaling similar to what is seen in PV [13]. This EPOR mutation has been shown to be associated with autosomal dominant erythrocytosis [14] and also reported as a de novo alteration [15, 16]. Taken together, this information supported a diagnosis of autosomal dominant hereditary or familial erythrocytosis type 1. Most patients with EPOR mutations are asymptomatic; with isolated cases experiencing cardiovascular complications and deep vein thrombosis [17]. While phlebotomy may benefit some patients in alleviating symptoms, it does not appear to have a protective effect with regards to cardiovascular events [18]. In terms of management, optimal hypertension control with lisinopril was emphasized and low-dose aspirin initiated. Since our patient was asymptomatic, routine phlebotomy was not recommended, however, phlebotomy prior to kidney donation was a consideration.

Case 2: Secondary erythrocytosis associated with cerebrovascular malformations

A 17-year-old Caucasian male, a high school student from Missouri was referred for evaluation of unexplained erythrocytosis. He reported a myriad of symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weight loss, fatigue, headaches, cold hands and feet with numbness and tingling, hyperhidrosis, palpitations, and pruritus. He was a non-smoker without illicit drug or hormone use. Family history was unremarkable. On physical examination, no cutaneous, abdominal or neurological abnormalities were noted. A review of serial blood counts showed a consistent elevation in Hgb >16.5 g/dl, with peak Hgb/Hct of 18.3 g/dl/52.4% and normal leukocyte and platelet counts. PV was excluded with a negative JAK2V617F/exon 12 mutation screen and elevated EPO at 22.6 mIU/mL (normal range; 2.6–18.5 mIU/mL). Bone marrow aspirate/biopsy was without features of a MPN. Hereditary erythrocytosis evaluation did not reveal high-affinity Hgb variants or mutations in 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate Mutase (BPGM)(exons 1–4), EPOR (exon 8), or oxygen‐sensing pathway proteins, including hypoxia-inducible factor 2 α (HIF2A) encoded by endothelial PASS domain protein 1 (EPAS1) (exons 9 and 12), prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) encoded by egl-9 family hypoxia-inducible factor 1(EGLN1)(exons 1-5), von Hippel Lindau (VHL) (three coding exons and intron/exon boundaries). Chest/abdominal imaging, arterial blood gas, transthoracic echocardiogram with shunt study, urinary catecholamines/metanephrines were unremarkable. Interestingly, MRI brain/spine revealed multiple cerebrovascular malformations; both developmental venous anomalies and cavernous hemangiomas in the frontal and temporal regions. Accordingly, the cerebrovascular malformations were hypothesized to be a plausible link to the patient’s erythrocytosis. Surgical intervention was not feasible due to the presence of multiple anomalies. He was initiated on phlebotomies with marked improvement in symptoms; thereafter, need for periodic phlebotomies was determined by symptoms rather than a target Hct value. This previously published case underscores the importance of a systematic diagnostic approach to JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis [19].

Case 3: “Idiopathic” erythrocytosis (erythrocytosis not otherwise specified)

Sixty-six-year-old lady from Minnesota with history of mild asthma, recurrent generalized anxiety, and episodic hypertension with possible right subclavian steal, was referred for evaluation of erythrocytosis. Complete blood count revealed Hgb of 19.3 g/dL, Hct of 58%, leukocytes 6.5 × 109/l, and platelet count of 349 × 109/l. Historical blood count review noted Hgb of 18.6 g/dl four years prior with progressive rise in Hgb >19 g/dl. Family history was unremarkable, and the patient was a non-smoker, without history of thrombosis, or aquagenic pruritus. Her dominant symptoms included severe headaches and fatigue. Physical exam revealed hypertension, normal oxygen saturation, without palpable hepatosplenomegaly. EPO level was in the normal range at 13.9 mIU/mL and JAK2V617F/exon 12 mutation analyses were negative. Bone marrow examination lacked features of MPN. Abdominal ultrasound did not reveal renal or hepatic lesions or evidence for renal artery stenosis. CT head was without intracranial abnormalities. Sleep apnea was excluded by overnight oximetry. Monoclonal protein studies and pheochromocytoma evaluation with urinary catecholamines/metanephrines were also obtained and unrevealing. In addition, hereditary erythrocytosis workup including high-oxygen affinity Hgb variants, EPOR, BPGM, VHL, PHD2, HIF2A mutation testing was unrevealing. In the absence of a specific etiology for erythrocytosis, our working diagnosis was “idiopathic” erythrocytosis or erythrocytosis not otherwise specified. She was recommended aspirin 81 mg daily and initiated on phlebotomy due to her symptoms and labile hypertension. The need for periodic phlebotomy was based upon symptoms. At six-month follow-up, Hgb remained below 16 g/dl without phlebotomy, along with resolution of headaches and hypertension. We recommended close monitoring of blood counts every 3–6 months.

Pathogenetic mechanisms in hypoxia-induced secondary erythrocytosis

The HIF pathway regulates erythropoiesis and EPO production within renal peritubular cells, in an oxygen-dependent manner [20,21,22]. HIF transcription factor is a heterodimer with alpha and beta subunits, the latter is constitutively expressed, while hypoxia affects the function of the former. HIF-A has three known isoforms (HIF-1A, HIF2A, HIF-3A), amongst which HIF2A is mainly involved in regulation of EPO synthesis; HIF2A knockout mice demonstrate a hypocellular marrow and anemia as a result of inadequate EPO production [23]. In the presence of oxygen, HIF2A undergoes hydroxylation at two critical proline residues, Pro405 and Pro531, mediated by PHD2 [24, 25], following which it undergoes degradation by the ubiquitin proteasomal pathway, a process mediated by VHL, a tumor suppressor protein, serving as the substrate recognition component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [26]. In addition, a 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenase, factor inhibiting HIF (FIH), catalyzes hydroxylation of a specific arginine residue within HIF which inhibits HIF binding to p300, a transcriptional co-activator [27]. The end result is reduced transcriptional activation of EPO; a HIF target gene.

Conversely, under hypoxic conditions, PHD2 enzymatic activity is reduced, resulting in diminished hydroxylation and degradation of HIF2A, in other words stabilization of HIF2A following which the HIF complex binds hypoxia responsive elements within the EPO gene and turns on its transcription [28,29,30]. This constitutes the pathogenetic basis for hypoxia-induced acquired erythrocytosis associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cyanotic heart disease with right to left shunt, and high-altitude habitat. Amelioration of tissue hypoxia reverses the process resulting in compensated normal EPO in such conditions, consistent with the assertion that regulation of erythropoiesis by HIF is exquisitely sensitive to oxygen levels [31, 32]. In addition, HIF2A expression is also controlled by iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 (Irps) via its iron-responsive elements, and deletion of Irp1 in murine studies has been found to increase HIF2A expression, which in turn stimulates EPO, leading to erythrocytosis [33].

Pathogenetic mechanisms in hereditary erythrocytosis

Germline VHL/HIF2A/PHD mutations

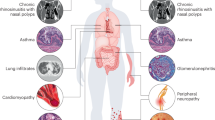

Germline mutations in the oxygen-sensing (VHL-HIF2A-PHD) pathway genes are relatively rare but when present may result in erythrocytosis with elevated or inappropriately normal EPO [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. It is to be noted that interrogation of this pathway is an evolving area of investigation with recent identification of novel zinc finger domain PHD2 mutations and splicing mutations in VHL [44, 45]. In chronological order (Fig. 1), in 1997, Chuvash polycythemia (CP), an autosomal recessive condition with homozygous VHL (R200W) mutation was initially described in Chuvashia (Russia) and subsequently noted in the Italian island of Ischia and worldwide [34, 35, 46, 47]. Functionally, VHL–HIF2A interaction is disrupted with impaired ability of VHL to target hydroxylated HIF2A for proteasomal degradation, resulting in increased HIF2A and EPO levels under normoxic conditions [34]. In addition, mutant VHL exhibits altered affinity for suppressor of cytokine signaling 1, impeding formation of a heterodimeric E3 ligase involved in targeting phosphorylated JAK2 for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation [48]. Accordingly, erythroid progenitors in affected patients also displayed hypersensitivity to EPO, which is an inherent feature shared by PV. In contrast to what is seen with the autosomal dominant “VHL syndrome”, malignant and benign tumors, including spinocerebellar hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytoma and renal cell carcinoma are not seen in patients with CP, reflecting the differential impact of the mutation in terms of HIF regulation [49]. On the other hand, erythrocytosis seldom accompanies “VHL syndrome” and is typically mediated by ectopic EPO production by tumor [50, 51].

In 2006, a PHD2 mutation (P317R) was implicated in a family with erythrocytosis; EPO levels were inappropriately normal, pointing toward secondary erythrocytosis [37]. The loss of function PHD2 mutations (P317R and the P371H variants), affect the catalytic rate and substrate-binding of PHD2, thereby hindering HIF hydroxylation. These mutations are not typically associated with tumors except for a patient with a recurrent extra-adrenal paraganglioma harboring the PHD2 H374R mutation [39].

In 2008, a heterozygous missense gain of function HIF2A mutation, located near the primary site of HIF hydroxylation (Pro531) was discovered upon investigation of a family with erythrocytosis; the particular mutation results in stabilization of HIF2A due to impaired hydroxylation [40]. HIF2A mutations may be associated with neuroendocrine tumors with a recent genotype/phenotype study describing the clinical spectrum of HIF2A mediated diseases (n = 66): class 1a (n = 6, sporadic) with pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, somatostatinoma and erythrocytosis; class 1b (n = 12; 1 familial, 11 sporadic) with pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma and erythrocytosis; class 1c (n = 20; all sporadic) with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, and class 2 (n = 28; 9 familial, 6 sporadic) with erythrocytosis alone. Each class was found to be driven by a unique set of non-overlapping mutations with class 1 mutations typically located between amino acid residues 529 and 532, which contain Pro531, whereas, class 2 mutations were found exclusively between residues 533 and 540. These findings highlight the differential impact of HIF2A mutations on HIF2A-VHL interaction with higher HIF2A levels implicated in tumorigenesis (class 1 disease) as opposed to slight increases in HIF2A activity that are sufficient to induce erythrocytosis in class 2 disease [52].

EPOR mutation

EPO binds to its receptor (EPOR) on the erythroid progenitor surface, which is part of the cytokine class I receptor superfamily; the receptor subsequently undergoes dimerization and activates JAK2, which in turn leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of its distal region [53]. EPO-induced JAK2 activation leads to intracellular activation of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways, and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT 1, 3, 5A, 5B), which turn on numerous target genes that promote red cell survival, proliferation and maturation [53]. In essence, EPO in synergy with several growth factors (SCF, GM-CSF, 1L-3, and IGF-1) enhances red cell survival by inhibition of apoptosis together with maturation and proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells. Germline heterozygous nonsense and frameshift mutations in exon 8 of EPOR have been described causing truncation of the C-terminal distal portion of the receptor which contains several tyrosine residues that serve as docking sites for SHP1, SOCS3 that are negative regulators of EPO signaling [14, 54,55,56]. This results in hypersensitivity to EPO via excessive activation of the EPO receptor [57,58,59].

Recently, mutations in the EPO gene itself have been identified in relation to familial erythrocytosis whereby a single base pair deletion in exon 2 caused a frameshift that truncated translation of the main EPO messenger RNA (mRNA), but converted a typically noncoding mRNA, which was transcribed from an alternative promoter within intron 1, to produce excess functional EPO mainly through the liver [60]. In addition, in a five-generation kindred with erythrocytosis, a novel heterozygous 5′UTR EPO variant has been newly discovered; the mutated 5′UTR of EPO augments interaction with HIF2, leading to increased production of EPO [61].

Altered oxygen affinity (high-oxygen-affinity Hgb variants and 2, 3 BPGM deficiency)

Structurally, Hgb is a tetramer, comprising of two alpha and beta globin subunits (an α1β1 dimer and an α2β2 dimer in Hgb A) with two conformationally stable states; the relaxed (R), high-oxygen affinity state and tense (T), low-oxygen affinity state [62, 63]. Oxygen binding to Hgb subunits demonstrates cooperativity, resulting in a sigmoidal oxygen dissociation curve which is left-shifted (low p50) with high-affinity variants [64]. The R–T transition is impacted by mutations in critical regions of the globin chain in high-affinity variants. Oxygen delivery is compromised at the tissue capillary level, resulting in hypoxia which serves as a stimulus for EPO production and subsequent erythrocytosis. Almost, 100 high-oxygen affinity Hgb variants have been reported [65]; a review of the Mayo Clinic Hgb variant database (1974-2018) identified 762 patients with 80 distinct variants (61 β, 20 α) [66]. These mutations were mostly missense impacting the heme pocket, α1β2 contact sites, 2, 3 BPG binding sites and C-terminal conformation stabilization regions, with the most common variants being Hb Tarrant (α chain variant) and Hb Malmo (β chain variant) [66]. Only one-third of high-affinity variants give rise to erythrocytosis, likely a result of either low‐level expression of the variant or concomitant hemolysis [65, 67]. Within red cells, 2, 3, BPGM catalyzes conversion of 1, 2 BPG to 2, 3 BPG, the latter binds deoxy Hgb tetramer and allosterically converts it to a low-oxygen affinity state, prompting release of oxygen. However, with 2, 3 BPGM deficiency, conversion of 1, 2 BPG to 2, 3 BPG is impaired, which enables the Hgb tetramer to assume a high-oxygen affinity state. Erythrocytosis resulting from 2, 3 BPG deficiency is relatively uncommon with limited cases described in the literature [68, 69].

Diagnostic approach

In clinical practice, hematology referrals for erythrocytosis are triggered by Hgb/Hct level above 16.5 g/dl/49% and 16 g/dl/48% in Caucasian males and females, respectively, and should be confirmed by at least two separate blood counts evaluated at different time points. This should be followed by distinguishing true from apparent erythrocytosis; the former is a result of either a clonal MPN, as in PV, or a non-clonal process resulting in secondary erythrocytosis. It is also important to recognize inapparent (masked) erythrocytosis in which an increase in red cell mass (RCM) is accompanied by a concomitant increase in plasma volume and therefore masked by a normal Hgb/Hct. Similarly, in situations with normal Hgb/Hct and concomitant iron deficiency, PV is often underrecognized. Conversely, an apparent erythrocytosis may result from either a reduction in plasma volume (relative erythrocytosis) or extreme high normal values which exceed the 95th percentile of sex-, race-and altitude-adjusted normal values. RCM measurement is no longer available at our institution; however, upon evaluation of its performance and practical utility in a total of 105 patients with erythrocytosis; elevated RCM was seen in 76%, 20%, 21%, and 57% with PV, secondary erythrocytosis, apparent erythrocytosis, and essential thrombocythemia, respectively. In the particular study RCM significantly correlated with both Hct and Hgb levels (p < 0.001). Hgb/Hct values below which an elevated RCM was not observed were 16/48% for males and 13/39% for females. In contrast, values >19.5/58% for males and 17.5/53% for females were almost always associated with increased RCM [70]. In other words, RCM measurement was found to be suboptimal in distinguishing PV from other causes of erythrocytosis and failed to offer any additional diagnostic value. Furthermore, obesity is a confounding factor that hinders accurate interpretation of RCM values [71].

During the evaluation of erythrocytosis, PV should always be considered and the diagnosis excluded by the absence of a JAK2 mutation (V617F exon 14 and exon 12) [72, 73]; also helpful in this regard is serum EPO especially in cases of JAK2V617F-negative but exon 12 mutated PV, where serum EPO levels are often subnormal [74]. If PV is suspected clinically or EPO is subnormal with the absence of JAK2V617F, a bone marrow examination is recommended in order to identify histological features associated with MPN. Additional testing for MPN associated mutations; CALR and SH2B3/LNK, albeit rarely found in PV, may be pursued [75,76,77,78,79]. Though predating molecular designations and not uniformly performed, in centers where available, bone marrow erythroid progenitor cultures may be a useful adjunct to rule-out endogenous erythroid proliferation [80, 81]. According to a seminal study on the subject, endogenous erythroid colonies were noted in the vast majority of PV (43 of 46) and in 0 of 17 secondary erythrocytosis cases [82], substantiating the enduring value of this test.

Once PV has been conclusively ruled out, we entertain the possibility of either hereditary or acquired erythrocytosis and commence our workup by reviewing prior blood counts when available in order to determine the duration of erythrocytosis. Figure 2 reviews our diagnostic algorithm which hinges upon duration of erythrocytosis (if known) and EPO levels.

Workup for suspected hereditary erythrocytosis

Hereditary erythrocytosis is suspected in children and young adults with long-standing erythrocytosis, particularly with a positive family history [83, 84]. A subnormal serum EPO level is suspicious for the presence of an EPOR mutation, as illustrated in Case 1. On the other hand, if serum EPO is normal or elevated, we proceed with venous p50 measurement (oxygen tension at which Hgb is 50% saturated). Venous p50 may also be calculated from venous blood gas using the following mathematical formula https://www.medsci.org/v04/p0232/ijmsv04p0232s1.xls [85].

A left shift of the oxygen dissociation curve, that is venous p50 < 24 mmHg may result from high-oxygen affinity Hgb, defective 2,3 BPG mutase causing 2, 3 BPG deficiency or methemoglobinemia [66]. Detection of high-oxygen-affinity Hgb variants is accomplished by cation exchange HPLC, capillary electrophoresis, or mass spectrometry. Since HPLC is normal in one-third of cases, sequencing of HBB, HBA1, HBA2 genes is often necessary.

Mutations in the oxygen-sensing pathway (VHL, PHD2, HIF2A) do not affect the venous p50 measurement and EPO is either elevated or inappropriately normal; in this regard, it is important to note that serum EPO might be impacted by phlebotomy. Sequencing studies for VHL (exons 1–3), PHD2 (exons 1–5), HIF2A (exons 9 and 12) are performed. Our Mayo clinic laboratory experience lends to the rarity of the above entities; of 1192 cases tested for hereditary erythrocytosis only 143 (12%) cases had identified abnormalities of which 85 were pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations (inclusive of alpha and beta high-oxygen affinity Hgb) and 58 variants of unknown significance [66]. Phenotypically, the majority of patients with high-oxygen affinity Hgb variants are asymptomatic [67].

Diagnostic approach in acquired erythrocytosis

A workup for acquired erythrocytosis warrants a thorough medical evaluation with attention to place of residence, tobacco use, along with a careful review of medications both prescription and supplements particularly testosterone, androgen, erythropoietin, diuretics, and certain antidiabetic agents (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; e.g., canagliflozin). Physical examination should focus on identifying hypoxia, cardiopulmonary disease, telangiectasias, cushingoid or virilization features, and abdominal masses raising concern for renal or hepatic tumors. Initial testing should include arterial blood gas, overnight oximetry, and abdominal ultrasound to assess for renal/hepatic tumors/renal artery stenosis. Further investigations are dictated by clinical findings; in the instance of neurological symptoms, brain imaging is of utility as in Case 2. An echocardiogram with shunt study is indicated in the presence of relevant cardiac findings. In females, myomatous erythrocytosis syndrome should be kept in mind, particularly since erythrocytosis is often masked by menorrhagia [86]. Rare acquired disorders to consider include the monoclonal gammopathy driven TEMPI syndrome which is characterized by telangiectasias, elevated serum EPO (which might be >5000 mIU/ml) and erythrocytosis, monoclonal gammopathy, perinephric fluid collections and intrapulmonary shunting [87, 88]; erythrocytosis and telangiectasis are often the initial manifestation, therefore obtaining monoclonal protein studies might provide diagnostic clues to this entity. Similarly, erythrocytosis along with thrombocytosis may be a part of polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M‐protein, skin changes syndrome [89].

Idiopathic erythrocytosis

In a high proportion (70%) of patients with erythrocytosis, a specific etiology remains elusive despite extensive testing; such cases are often referred to as “idiopathic” or “not otherwise specified” [7, 55]. In rare instances, SH2B3/LNK exon 2 mutations or polymorphisms have been reported in patients with unexplained erythrocytosis, with subnormal serum EPO levels, and absence of JAK2, MPL, and EPOR mutations [90, 91]. For instance, LNK mutations were detected in 6 of 112 (5.3%) of patients with JAK2 negative erythrocytosis, assumed to be idiopathic [92]. In patients with clinical suspicion of hereditary erythrocytosis, aberrant functioning of proteins involved in the oxygen-sensing pathway (PHD2-HIF2A-VHL-EPO) and erythropoiesis have a high likelihood of being implicated, hence expanded gene/exome sequencing should be offered if available on a research basis in order to uncover novel variants/polymorphisms [7]. Recently, pathogenic mutations in the PIEZO1 gene were noted in up to 4% of individuals with idiopathic erythrocytosis, in association with clinical or biological manifestations of hereditary xerocytosis (HX)(iron overload, splenomegaly, hemolysis, decreased venous p50) [93]. In a large series of patients with HX and PIEZO1 mutations, 68% were not anemic; moreover, 7 adults had Hgb >16 g/dl, with two patients known to have erythrocytosis [94]. Functionally, Piezo1-HX affects red cell energy metabolism and glycolysis, resulting in reduced BPG levels, conferring a high-oxygen affinity state, which explains the basis for erythrocytosis in this disorder [95]. Another rare entity to consider particularly in children with unexplained erythrocytosis are SLC30A10 mutations, which occurs in association with hypermanganesemia, parkinsonism, and hepatic cirrhosis [96].

Continued monitoring of cases with unexplained erythrocytosis is advised, especially in those where information on JAK2 mutation is not available. Not surprisingly, in comparison to patients with PV, those with idiopathic erythrocytosis were more likely to be males and display lower white and platelet count, higher EPO levels, lower lactate dehydrogenase levels, absence of palpable splenomegaly or thrombosis [11, 97]. In the particular study, phlebotomy led to elevation in leukocyte and platelet count in PV but not in idiopathic erythrocytosis [97]. Another report comparing 145 patients with idiopathic erythrocytosis and PV also confirmed a lower incidence of thrombosis and bleeding with idiopathic erythrocytosis [98].

Management

A dearth of compelling evidence defining optimal management strategies for JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis stems from the heterogeneity in associated hereditary and acquired disorders. Hence, it is common practice to inadvertently extrapolate outcomes from studies conducted in PV patients or follow consensus guidelines [99, 100]. In order to formulate our recommendations that have been summarized in Fig. 3, we reviewed the relevant literature pertaining to secondary erythrocytosis associated with common acquired and hereditary conditions (Table 1). Data regarding thrombosis risk in acquired secondary erythrocytosis has been conflicting; while the majority of studies do not support an increased thrombotic risk [101,102,103], two recent studies have implied the contrary [5, 11]. In a noteworthy large population-based series, erythrocytosis defined by higher Hgb/Hct thresholds, as per the 2008 WHO criteria, was associated with higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [5]; however, details of conditions associated with erythrocytosis were not specified but a high incidence (38%) of clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular risk factors were reported accounting for a higher incidence of cardiovascular events. In a second smaller series of 35 patients with secondary erythrocytosis, thrombosis rates at or prior to diagnosis were similar to those reported in PV, which is likely explained by the clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in those with secondary erythrocytosis [11].

On the other hand, phlebotomy might be detrimental to patients with COPD or in adults with cyanotic heart disease and CP, in terms of thrombosis risk [103,104,105,106]. Therefore, the institution of phlebotomy in such cases requires careful assessment of risk-benefit balance. The same is true for most cases of secondary erythrocytosis. Moreover, transient symptom relief from phlebotomy is often complicated by a vicious cycle precipitated by depletion of iron stores, resulting in inhibition of PHD2, stabilization of HIF, and increased Epo mediated erythropoiesis. Furthermore, rigid microcytic red cells that are associated with phlebotomy-induced iron deficiency have an inherent tendency to exacerbate hyper-viscosity. Taken together, phlebotomy should be reserved for relief of symptoms with documented response to the particular treatment modality; reported symptoms in patients with non-clonal erythrocytosis include fatigue, generalized weakness, headaches, visual changes, mental fog, tinnitus, chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, abdominal and bone pain. Similar symptoms can be seen with phlebotomy-induced dehydration and iron deficiency, and therefore should be concomitantly addressed. Aspirin 81 mg daily should be instituted in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors. Arterial and venous thromboses are managed with antiplatelet agents and systemic anticoagulation respectively.

Management specifics in patients with hypoxic pulmonary disease, including COPD

The incidence of erythrocytosis in COPD ranges from 5.9 to 18.1% and is declining with the implementation of long-term oxygen therapy [107, 108]. Patients are often referred to hematology to address risks for thrombosis and optimal Hct control. Amongst 86 COPD patients with erythrocytosis, retrospectively compared with age- and sex-matched COPD patients without erythrocytosis, no difference in the incidence of venous thromboembolism was recorded: 19.8%vs 14%; p = 0.42 [101]. Another study investigated the impact of phlebotomy on prevalence of arterial and venous thrombosis in COPD with erythrocytosis and found similar thrombosis rates in phlebotomized (31%) vs non-phlebotomized (22%) patients (p = 0.28) [109]. Moreover, amongst phlebotomized COPD patients, stringent Hct control did not appear to influence the incidence of thrombosis; 25% with Hct <52% vs 37% at higher Hct levels (p = 0.45) [109]. These observations are supportive of restricting phlebotomy in COPD to only those patients whose symptoms can clearly be correlated to the increased Hct with documentation of symptom relief from phlebotomy [110]. Furthermore, smoking cessation counseling should be provided when applicable. Management of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) includes referral to a sleep specialist for institution of overnight continuous positive airway pressure. It is to be noted that in a large study of 1604 patients with suspected OSA, only 1.6% had erythrocytosis defined by Hct ≥51% and 48% in males and females, respectively [111].

Management specifics in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease

A retrospective study on 162 adults with erythrocytosis in association with cyanotic heart disease, reported a higher incidence of cerebrovascular events in patients treated with phlebotomy. In that particular study, patients were stratified into two groups based on absence/presence of prior cerebrovascular events; Group 1 (n = 140) and Group 2 (n = 22), respectively. Amongst 46/162 (28%) of patients that underwent phlebotomy, cerebral events occurred in 25% of Group 1 (n = 35) vs 50% of Group 2 (n = 11), (p = 0.016). Other noteworthy findings were a strong association of iron deficiency and/or microcytosis with cerebrovascular events; reported in 11/41(27%) with iron deficiency; p = 0.004. As a result, phlebotomy with volume replacement should be used sparingly for mere symptom relief only when Hct rises above 65%. We also encourage collaborative care with an adult congenital cardiologist [112]. In terms of alternatives to phlebotomy, when 4 patients with symptomatic secondary erythrocytosis and congenital heart disease were treated with hydroxyurea, symptom relief was achieved but without a clear impact on thrombosis risk and at the cost of myelosuppression requiring dose reduction in three patients [113].

Management specifics in post-renal transplant erythrocytosis

Incidence of erythrocytosis after renal transplant ranges from 8 to 15% and has been associated with increased risk of thromboembolic events [114]. The mechanism remains obscure but excessive Epo production may be driven by angiotensin-II [115]. Accordingly, both ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have been used to control post-renal transplant erythrocytosis, obviating the need for intermittent phlebotomy. The use of enalapril in post-transplant erythrocytosis was studied in a randomized fashion with administration of either 2.5 mg of enalapril daily (n = 15) or placebo (n = 10) for 4 months. Hct decreased from 52.7 to 47.1 at 1 month and to 46.1 after 4 months of therapy with enalapril; no change with placebo (p = 0.004) without any thrombotic events [116]. Similarly, both enalapril and losartan were also evaluated in a prospective randomized study, and both drugs showed a significant decline in Hgb [117]. Theophylline is another agent, which significantly reduced Hct and Epo levels in renal transplant patients (58– 46%; 60–9 units; p < 0.05) vs controls (43–39%; 6.9–4.7 units; p < 0.05), thereby eliminating requirement of weekly phlebotomy [118].

Management specifics in patients on androgen therapy

Erythrocytosis may develop in men with androgen deficiency receiving testosterone therapy [119, 120]. Androgen replacement is generally not advised when Hct is >50%. In patients with Hct above 54%, testosterone is withheld until Hct is at an acceptable level below 50%, and therapy resumed at a reduced dose [121]. Amongst 234 transgenders receiving testosterone, with mean Hgb 13.5 g/dL and Hct 40.3% (pre-testosterone), Hgb peaked at 15.7 g/dl, Hct 47.2% at an average of 21 months post therapy [122]. Approximately a quarter of patients developed Hct >50%, one thrombotic event recorded, and dose reduction was implemented in 14.5% of patients with erythrocytosis [122].

Management specifics in patients with hereditary erythrocytosis

Amongst hereditary conditions associated with erythrocytosis, CP is the only one with a well-defined natural history. It is phenotypically characterized by low systemic blood pressure, body mass index, and white count, with an unusual propensity for vascular events leading to early mortality from both cerebrovascular events and peripheral thrombosis [46]. In a prospective study of 155 CP patients, control-matched by age, sex, and place of residence, the rate of new thrombotic events was considerably higher in CP (37 arterial and venous events of which 9 were fatal) vs controls (5 arterial events) [106]. On multivariate analysis, age and previous thrombotic event, but not Hct, were independent predictors of new events. Moreover, phlebotomy was associated with increased incidence of thrombosis (HR 1.9, p = 0.028). In the particular study, none of the patients were on systemic anticoagulation while approximately half were on aspirin therapy at the time of the second event; however, aspirin 75 mg/day was not protective [106].

In addition, in a comparison of CP and PV patients; overall mortality was higher (47%) in CP vs 18.5% with PV, with a higher proportion of deaths due to cerebrovascular events or peripheral thrombosis (46.1% vs 21.9%), regardless of younger age (median age; 16 vs 60 years) [46]. In the particular study, 78% of CP patients received phlebotomy; with no significant benefit in thrombotic risk or mortality reduction, suggesting that thrombotic events are likely driven by factors beyond the high Hct, such as elevated vascular endothelial growth factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor- 1, 2 (PAI-1,2) and homocysteine levels [46]. In regards to drug therapy, in murine models administration of a highly selective JAK2 inhibitor, TG101209 was able to reverse the CP phenotype [48]. To date, three patients have been treated with ruxolitinib with each experiencing hematologic and symptomatic improvement, however, no impact on thrombotic events or mortality has been appreciated [123]. Based on the above, CP patients require close monitoring with stringent cardiovascular risk modification and antiplatelet therapy.

Meanwhile, in a recent prospective observation of eight patients that were part of a six-generation pedigree harboring the HIF2A p.M535V variant, arterial and venous thrombosis occurred in 5 of 8 patients vs no events in 17 HIF2A wild-type patients (p = 0.001). Moreover, thrombotic events occurred despite strict phlebotomy with Hct maintained below 45%, in the absence of cardiovascular risk factors [106].

Concluding remarks

The discovery of JAK2 exons 14 and 12 mutations in 2005 and 2007, respectively, and their almost invariable association with PV has greatly simplified our current diagnostic approach to erythrocytosis [73, 124]. This is because the most treatment-relevant step in addressing the differential diagnosis of erythrocytosis is the exclusion of PV, because of its specific association with increased risk of thrombosis and fibrotic/leukemic transformation. The increased utilization of peripheral blood JAK2 mutation screening has increased general awareness and recognition of non-PV erythrocytosis. In the current document, we have provided practical algorithms for both diagnosing and treating this condition. In this regard, the prompt and accurate distinction between underlying causes is decidedly crucial, as management is directly dictated by etiology, and incorrect diagnosis may lead to under or overtreatment. Promising discoveries within the last 3 years have included mutations in the EPO gene, novel zinc finger domain PHD2 mutations and splicing mutations in VHL [44, 45, 60]. Also, in the foreseeable future, we anticipate improved molecular characterization of the elusive entity, “idiopathic erythrocytosis” [7]. Finally, prospective controlled studies are needed to confirm or further advance current treatment strategies in non-PV erythrocytosis.

References

Pearson TC. Apparent polycythaemia. Blood Rev. 1991;5:205–13.

Fairbanks VF, Tefferi A. Normal ranges for packed cell volume and hemoglobin concentration in adults: relevance to ‘apparent polycythemia’. Eur J Haematol. 2000;65:285–96.

Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–51.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–405.

Wouters H, Mulder R, van Zeventer IA, Schuringa JJ, van der Klauw MM, van der Harst P, et al. Erythrocytosis in the general population: clinical characteristics and association with clonal hematopoiesis. Blood Adv. 2020;4:6353–63.

Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. The complete evaluation of erythrocytosis: congenital and acquired. Leukemia 2009;23:834–44.

Camps C, Petousi N, Bento C, Cario H, Copley RR, McMullin MF, et al. Gene panel sequencing improves the diagnostic work-up of patients with idiopathic erythrocytosis and identifies new mutations. Haematologica. 2016;101:1306–18.

McMullin MF. Idiopathic erythrocytosis: a disappearing entity. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:629–35. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.629.

Bento C, Almeida H, Maia TM, Relvas L, Oliveira AC, Rossi C, et al. Molecular study of congenital erythrocytosis in 70 unrelated patients revealed a potential causal mutation in less than half of the cases (Where is/are the missing gene(s)?). Eur J Haematol. 2013;91:361–8.

Rumi E, McMullin MF, Harrison C, Ellis MH, Barzilai M, Sarid N, et al. Facing erythrocytosis: results of an international physician survey. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:E225–E7.

Nguyen E, Szuber N, Harnois M, Busque L, Mollica L, Assouline SE, et al. Secondary erythrocytosis is phenotypically distinct from polycythemia vera but associated with comparable rates of thrombosis at diagnosis. Blood. 2020;136:4–7.

Huang LJ, Shen YM, Bulut GB. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of primary familial and congenital polycythaemia. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:844–52.

Pasquier F, Marty C, Balligand T, Verdier F, Grosjean S, Gryshkova V, et al. New pathogenic mechanisms induced by germline erythropoietin receptor mutations in primary erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2018;103:575–86.

de la Chapelle A, Traskelin AL, Juvonen E. Truncated erythropoietin receptor causes dominantly inherited benign human erythrocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4495–9.

Rives S, Pahl HL, Florensa L, Bellosillo B, Neusuess A, Estella J, et al. Molecular genetic analyses in familial and sporadic congenital primary erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2007;92:674–7.

Percy MJ, McMullin MF, Roques AW, Westwood NB, Acharya J, Hughes AE, et al. Erythrocytosis due to a mutation in the erythropoietin receptor gene. Br J Haematol. 1998;100:407–10.

Bento C, Percy MJ, Gardie B, Maia TM, van Wijk R, Perrotta S, et al. Genetic basis of congenital erythrocytosis: mutation update and online databases. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:15–26.

Kralovics R, Sokol L, Prchal JT. Absence of polycythemia in a child with a unique erythropoietin receptor mutation in a family with autosomal dominant primary polycythemia. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:124–9.

Gangat N, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Erythrocytosis associated with cerebral hemangiomas and multiple venous anomalies. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:1224–5.

Wenger RH, Hoogewijs D. Regulated oxygen sensing by protein hydroxylation in renal erythropoietin-producing cells. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2010;298:F1287–96.

Haase VH. Regulation of erythropoiesis by hypoxia-inducible factors. Blood Rev. 2013;27:41–53.

Lappin TR, Lee FS. Update on mutations in the HIF: EPO pathway and their role in erythrocytosis. Blood Rev. 2019;37:100590.

Scortegagna M, Morris MA, Oktay Y, Bennett M, Garcia JA. The HIF family member EPAS1/HIF-2alpha is required for normal hematopoiesis in mice. Blood. 2003;102:1634–40.

Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M, et al. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–8.

Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–72.

Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–5.

Mahon PC, Hirota K, Semenza GL. FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1alpha and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2675–86.

Semenza GL, Wang GL. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5447–54.

Wang GL, Semenza GL. General involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in transcriptional response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4304–8.

Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5510–4.

Jewell UR, Kvietikova I, Scheid A, Bauer C, Wenger RH, Gassmann M. Induction of HIF-1alpha in response to hypoxia is instantaneous. FASEB J. 2001;15:1312–4.

Fandrey J, Gorr TA, Gassmann M. Regulating cellular oxygen sensing by hydroxylation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;71:642–51.

Ghosh MC, Zhang DL, Jeong SY, Kovtunovych G, Ollivierre-Wilson H, Noguchi A, et al. Deletion of iron regulatory protein 1 causes polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in mice through translational derepression of HIF2alpha. Cell Metab. 2013;17:271–81.

Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, Gordeuk VR, Jelinek J, Guan Y, et al. Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet. 2002;32:614–21.

Tomasic NL, Piterkova L, Huff C, Bilic E, Yoon D, Miasnikova GY, et al. The phenotype of polycythemia due to Croatian homozygous VHL (571C>G:H191D) mutation is different from that of Chuvash polycythemia (VHL 598C>T:R200W). Haematologica. 2013;98:560–7.

Pastore Y, Jedlickova K, Guan Y, Liu E, Fahner J, Hasle H, et al. Mutations of von Hippel-Lindau tumor-suppressor gene and congenital polycythemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:412–9.

Percy MJ, Zhao Q, Flores A, Harrison C, Lappin TR, Maxwell PH, et al. A family with erythrocytosis establishes a role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:654–9.

Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Beer PA, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS. A novel erythrocytosis-associated PHD2 mutation suggests the location of a HIF binding groove. Blood. 2007;110:2193–6.

Ladroue C, Carcenac R, Leporrier M, Gad S, Le Hello C, Galateau-Salle F, et al. PHD2 mutation and congenital erythrocytosis with paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2685–92.

Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Lucas GS, Li X, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in the HIF2A gene in familial erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:162–8.

Zhuang Z, Yang C, Lorenzo F, Merino M, Fojo T, Kebebew E, et al. Somatic HIF2A gain-of-function mutations in paraganglioma with polycythemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:922–30.

Yang C, Sun MG, Matro J, Huynh TT, Rahimpour S, Prchal JT, et al. Novel HIF2A mutations disrupt oxygen sensing, leading to polycythemia, paragangliomas, and somatostatinomas. Blood. 2013;121:2563–6.

Comino-Mendez I, de Cubas AA, Bernal C, Alvarez-Escola C, Sanchez-Malo C, Ramirez-Tortosa CL, et al. Tumoral EPAS1 (HIF2A) mutations explain sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in the absence of erythrocytosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2169–76.

Sinnema M, Song D, Guan W, Janssen JWH, van Wijk R, Navalsky BE, et al. Loss-of-function zinc finger mutation in the EGLN1 gene associated with erythrocytosis. Blood. 2018;132:1455–8.

Lenglet M, Robriquet F, Schwarz K, Camps C, Couturier A, Hoogewijs D, et al. Identification of a new VHL exon and complex splicing alterations in familial erythrocytosis or von Hippel-Lindau disease. Blood. 2018;132:469–83.

Gordeuk VR, Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, Okhotin D, Voloshin Y, Choyke PL, et al. Congenital disorder of oxygen sensing: association of the homozygous Chuvash polycythemia VHL mutation with thrombosis and vascular abnormalities but not tumors. Blood. 2004;103:3924–32.

Sergeyeva A, Gordeuk VR, Tokarev YN, Sokol L, Prchal JF, Prchal JT. Congenital polycythemia in Chuvashia. Blood. 1997;89:2148–54.

Russell RC, Sufan RI, Zhou B, Heir P, Bunda S, Sybingco SS, et al. Loss of JAK2 regulation via a heterodimeric VHL-SOCS1 E3 ubiquitin ligase underlies Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Med. 2011;17:845–53.

Kim WY, Kaelin WG. Role of VHL gene mutation in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4991–5004.

Krieg M, Marti HH, Plate KH. Coexpression of erythropoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor in nervous system tumors associated with von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene loss of function. Blood. 1998;92:3388–93.

Da Silva JL, Lacombe C, Bruneval P, Casadevall N, Leporrier M, Camilleri JP, et al. Tumor cells are the site of erythropoietin synthesis in human renal cancers associated with polycythemia. Blood. 1990;75:577–82.

Tarade D, Robinson CM, Lee JE, Ohh M. HIF-2alpha-pVHL complex reveals broad genotype-phenotype correlations in HIF-2alpha-driven disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3359.

Kuhrt D, Wojchowski DM. Emerging EPO and EPO receptor regulators and signal transducers. Blood 2015;125:3536–41.

Vocanec D, Prijatelj T, Debeljak N, Kunej T. Genetic variants of erythropoietin (EPO) and EPO receptor genes in familial erythrocytosis. Int J Lab Hematol. 2019;41:162–7.

Filser M, Aral B, Airaud F, Chauveau A, Bruce A, Polfrit Y, et al. Low incidence of EPOR mutations in idiopathic erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2021;106:299–301.

de la Chapelle A, Sistonen P, Lehvaslaiho H, Ikkala E, Juvonen E. Familial erythrocytosis genetically linked to erythropoietin receptor gene. Lancet. 1993;341:82–4.

Sokol L, Luhovy M, Guan Y, Prchal JF, Semenza GL, Prchal JT. Primary familial polycythemia: a frameshift mutation in the erythropoietin receptor gene and increased sensitivity of erythroid progenitors to erythropoietin. Blood. 1995;86:15–22.

Perrotta S, Cucciolla V, Ferraro M, Ronzoni L, Tramontano A, Rossi F, et al. EPO receptor gain-of-function causes hereditary polycythemia, alters CD34 cell differentiation and increases circulating endothelial precursors. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12015.

Watowich SS, Xie X, Klingmuller U, Kere J, Lindlof M, Berglund S, et al. Erythropoietin receptor mutations associated with familial erythrocytosis cause hypersensitivity to erythropoietin in the heterozygous state. Blood. 1999;94:2530–2.

Zmajkovic J, Lundberg P, Nienhold R, Torgersen ML, Sundan A, Waage A, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in EPO in familial erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:924–30.

Lanikova L, Song J, Babosova O, Berkova L, Korinek V, Prchal JT. Mutation of EPO 5’UTR facilitates interaction with HIF2 and causes autosomal dominant erythrocytosis. Blood. 2020;136:28-.

Perutz MF. Structure and mechanism of haemoglobin. Br Med Bull. 1976;32:195–208.

Perutz MF. Haemoglobin: structure, function and synthesis. Br Med Bull. 1976;32:193–4.

Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux JP. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118.

Yudin J, Verhovsek M. How we diagnose and manage altered oxygen affinity hemoglobin variants. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:597–603.

Oliveira JL, Coon LM, Frederick LA, Hein M, Swanson KC, Savedra ME, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of hereditary erythrocytosis mutations, a single center experience. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:1029–41.

Wajcman H, Galacteros F. Hemoglobins with high oxygen affinity leading to erythrocytosis. New variants and new concepts. Hemoglobin. 2005;29:91–106.

Rosa R, Prehu MO, Beuzard Y, Rosa J. The first case of a complete deficiency of diphosphoglycerate mutase in human erythrocytes. J Clin Investig. 1978;62:907–15.

Hoyer JD, Allen SL, Beutler E, Kubik K, West C, Fairbanks VF. Erythrocytosis due to bisphosphoglycerate mutase deficiency with concurrent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency. Am J Hematol. 2004;75:205–8.

Sirhan S, Fairbanks VF, Tefferi A. Red cell mass and plasma volume measurements in polycythemia: evaluation of performance and practical utility. Cancer. 2005;104:213–5.

Leslie WD, Dupont JO, Peterdy AE. Effect of obesity on red cell mass results. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:422–8.

Pardanani A, Lasho TL, Finke C, Hanson CA, Tefferi A. Prevalence and clinicopathologic correlates of JAK2 exon 12 mutations in JAK2V617F-negative polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2007;21:1960–3.

Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, Scott MA, Beer PA, Stratton MR, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:459–68.

Scott LM. The JAK2 exon 12 mutations: a comprehensive review. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:668–76.

Broseus J, Park JH, Carillo S, Hermouet S, Girodon F. Presence of calreticulin mutations in JAK2-negative polycythemia vera. Blood. 2014;124:3964–6.

Oh ST, Simonds EF, Jones C, Hale MB, Goltsev Y, Gibbs KD Jr., et al. Novel mutations in the inhibitory adaptor protein LNK drive JAK-STAT signaling in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2010;116:988–92.

Pardanani A, Lasho T, Finke C, Oh ST, Gotlib J, Tefferi A. LNK mutation studies in blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms, and in chronic-phase disease with TET2, IDH, JAK2 or MPL mutations. Leukemia. 2010;24:1713–8.

Xu N, Ding L, Yin C, Zhou X, Li L, Li Y, et al. A report on the co-occurrence of JAK2V617F and CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasm patients. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:865–7.

Chauveau A, Nibourel O, Tondeur S, Paz DL, Mansier O, Paul F, et al. Absence of CALR mutations in JAK2-negative polycythemia. Haematologica. 2017;102:e15–e6.

Dobo I, Donnard M, Girodon F, Mossuz P, Boiret N, Boukhari R, et al. Standardization and comparison of endogenous erythroid colony assays performed with bone marrow or blood progenitors for the diagnosis of polycythemia vera. Hematol J. 2004;5:161–7.

Dobo I, Mossuz P, Campos L, Girodon F, Allegraud A, Latger-Cannard V, et al. Comparison of four serum-free, cytokine-free media for analysis of endogenous erythroid colony growth in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Hematol J. 2001;2:396–403.

Lemoine F, Najman A, Baillou C, Stachowiak J, Boffa G, Aegerter P, et al. A prospective study of the value of bone marrow erythroid progenitor cultures in polycythemia. Blood. 1986;68:996–1002.

Bento C. Genetic basis of congenital erythrocytosis. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018;40:62–7.

Cario H, McMullin MF, Bento C, Pospisilova D, Percy MJ, Hussein K, et al. Erythrocytosis in children and adolescents-classification, characterization, and consensus recommendations for the diagnostic approach. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1734–8.

Agarwal N, Mojica-Henshaw MP, Simmons ED, Hussey D, Ou CN, Prchal JT. Familial polycythemia caused by a novel mutation in the beta globin gene: essential role of P50 in evaluation of familial polycythemia. Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:232–6.

Mui J, Yang MMH, Cohen T, McDonald DI, Hunt H. More than a myoma: a review of myomatous erythrocytosis syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42:198–203 e3.

Sykes DB, Schroyens W, O’Connell C. The TEMPI syndrome–a novel multisystem disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:475–7.

Sykes DB, O’Connell C, Schroyens W. The TEMPI syndrome. Blood. 2020;135:1199–203.

Dispenzieri A. POEMS Syndrome: 2019 Update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:812–27.

Lasho TL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. LNK mutations in JAK2 mutation-negative erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1189–90.

McMullin MF, Wu C, Percy MJ, Tong W. A nonsynonymous LNK polymorphism associated with idiopathic erythrocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:962–4.

Spolverini A, Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Pancrazzi A, Fanelli T, Paoli C, et al. Infrequent occurrence of mutations in the PH domain of LNK in patients with JAK2 mutation-negative ‘idiopathic’ erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2013;98:e101–2.

Filser M, Giansily-Blaizot M, Grenier M, Monedero Alonso D, Bouyer G, Peres L, et al. Increased incidence of germline PIEZO1 mutations in individuals with idiopathic erythrocytosis. Blood. 2021;137:1828–32.

Picard V, Guitton C, Thuret I, Rose C, Bendelac L, Ghazal K, et al. Clinical and biological features in PIEZO1-hereditary xerocytosis and Gardos channelopathy: a retrospective series of 126 patients. Haematologica 2019;104:1554–64.

Kiger L, Oliveira L, Guitton C, Bendelac L, Ghazal K, Proulle V, et al. Piezo1-xerocytosis red cell metabolome shows impaired glycolysis and increased hemoglobin oxygen affinity. Blood Adv. 2021;5:84–8.

Quadri M, Federico A, Zhao T, Breedveld GJ, Battisti C, Delnooz C, et al. Mutations in SLC30A10 cause parkinsonism and dystonia with hypermanganesemia, polycythemia, and chronic liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:467–77.

Randi ML, Bertozzi I, Cosi E, Santarossa C, Peroni E, Fabris F. Idiopathic erythrocytosis: a study of a large cohort with a long follow-up. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:233–7.

Bertozzi I, Ruggeri M, Nichele I, Biagetti G, Cosi E, Randi ML. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications in idiopathic erythrocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:E639–E41.

Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, Cacciola R, Cavazzina R, Cilloni D, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:22–33.

McMullin MFF, Mead AJ, Ali S, Cargo C, Chen F, Ewing J, et al. A guideline for the management of specific situations in polycythaemia vera and secondary erythrocytosis: a British Society for Haematology Guideline. Br J Haematol. 2019;184:161–75.

Nadeem O, Gui J, Ornstein DL. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with secondary polycythemia. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2013;19:363–6.

Lubarsky DA, Gallagher CJ, Berend JL. Secondary polycythemia does not increase the risk of perioperative hemorrhagic or thrombotic complications. J Clin Anesth. 1991;3:99–103.

Ammash N, Warnes CA. Cerebrovascular events in adult patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:768–72.

Perloff JK, Marelli AJ, Miner PD. Risk of stroke in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation 1993;87:1954–9.

Sergueeva A, Miasnikova G, Shah BN, Song J, Lisina E, Okhotin DJ, et al. Prospective study of thrombosis and thrombospondin-1 expression in Chuvash polycythemia. Haematologica. 2017;102:e166–e9.

Gordeuk VR, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, Lorenzo FR, Zhang X, Song J, et al. Thrombotic risk in congenital erythrocytosis due to up-regulated hypoxia sensing is not associated with elevated hematocrit. Haematologica. 2020;105:e87–e90.

Kollert F, Tippelt A, Muller C, Jorres RA, Porzelius C, Pfeifer M, et al. Hemoglobin levels above anemia thresholds are maximally predictive for long-term survival in COPD with chronic respiratory failure. Respir Care. 2013;58:1204–12.

Cote C, Zilberberg MD, Mody SH, Dordelly LJ, Celli B. Haemoglobin level and its clinical impact in a cohort of patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:923–9.

Mao C, Olszewski AJ, Egan PC, Barth P, Reagan JL. Evaluating the incidence of cardiovascular and thrombotic events in secondary polycythemia. Blood. 2019;134:3511.

Dayton LM, McCullougy RE, Scheinhorn DJ, Weil JV. Symptomatic and puomonary response to acute phlebotomy in secondary polycythemia. Chest. 1975;68:785–90.

Nguyen CD, Holty JC. Does untreated obstructive sleep apnea cause secondary erythrocytosis? Respir Med. 2017;130:27–34.

Thorne SA. Management of polycythaemia in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Heart. 1998;79:315–6.

Reiss UM, Bensimhon P, Zimmerman SA, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea therapy for management of secondary erythrocytosis in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:740–3.

Wickre CG, Norman DJ, Bennison A, Barry JM, Bennett WM. Postrenal transplant erythrocytosis: a review of 53 patients. Kidney Int. 1983;23:731–7.

Mrug M, Stopka T, Julian BA, Prchal JF, Prchal JT. Angiotensin II stimulates proliferation of normal early erythroid progenitors. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2310–4.

Beckingham IJ, Woodrow G, Hinwood M, Rigg KM, Morgan AG, Burden RP, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled study of enalapril in the treatment of erythrocytosis after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 1995;10:2316–20.

Yildiz A, Cine N, Akkaya V, Sahin S, Ismailoglu V, Turk S, et al. Comparison of the effects of enalapril and losartan on posttransplantation erythrocytosis in renal transplant recipients: prospective randomized study. Transplantation. 2001;72:542–4.

Bakris GL, Sauter ER, Hussey JL, Fisher JW, Gaber AO, Winsett R. Effects of theophylline on erythropoietin production in normal subjects and in patients with erythrocytosis after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:86–90.

Ohlander SJ, Varghese B, Pastuszak AW. Erythrocytosis following testosterone therapy. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:77–85.

Jones SD Jr., Dukovac T, Sangkum P, Yafi FA, Hellstrom WJ. Erythrocytosis and polycythemia secondary to testosterone replacement therapy in the aging male. Sex Med Rev. 2015;3:101–12.

Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536–59.

Oakes M, Kato C, Yazdani S, Deloughery TG, Milano C, Shatzel JJ, et al. The prevalence and management of secondary erythrocytosis in transgender individuals undergoing masculinizing therapy. Blood. 2020;136:13-.

Zhou AW, Knoche EM, Engle EK, Ban-Hoefen M, Kaiwar C, Oh ST. Clinical improvement with JAK2 inhibition in chuvash polycythemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:494–6.

James C, Ugo V, Le Couedic JP, Staerk J, Delhommeau F, Lacout C, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434:1144–8.

Chambellan A, Chailleux E, Similowski T., Prognostic value of the hematocrit in patients with severe COPD receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Chest. 2005;128:1201–8.

Ristić L, Rančić M, Radović M, Cirić Z, Kutlešić Kurtović D. Pulmonary embolism in chronic hypoxemic patients with and without secondary polycythemia–analysis of risk factors in prospective clinical study. Med Glas (Zenica). 2013;10:258–65.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NG, NS, AP, and AT co-wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gangat, N., Szuber, N., Pardanani, A. et al. JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis: current diagnostic approach and therapeutic views. Leukemia 35, 2166–2181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01290-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01290-6

This article is cited by

-

Idiopathic erythrocytosis: a germline disease?

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2024)

-

Diagnostic Approaches to Investigate JAK2-Unmutated Erythrocytosis Based on a Single Tertiary Center Experience

Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy (2024)

-

A novel germline hyperactivating JAK2 mutation L604F

Annals of Hematology (2023)

-

Potential limitations of diagnostic standard codes to distinguish polycythemia vera and secondary erythrocytosis

Scientific Reports (2022)