Abstract

We studied by questionnaire 530 subjects with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) in Hubei Province during the recent SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Five developed confirmed (N = 4) or probable COVID-19 (N = 1). Prevalence of COVID-19 in our subjects, 0.9% (95% Confidence Interval, 0.1, 1.8%) was ninefold higher than 0.1% (0, 0.12%) reported in normals but lower than 10% (6, 17%) reported in hospitalised persons with other haematological cancers or normal health-care providers, 7% (4, 12%). Co-variates associated with an increased risk of developing COVID-19 amongst persons with CML were exposure to someone infected with SARS-CoV-2 (P = 0.037), no complete haematologic response (P = 0.003) and co-morbidity(ies) (P = 0.024). There was also an increased risk of developing COVID-19 in subjects in advanced phase CML (P = 0.004) even when they achieved a complete cytogenetic response or major molecular response at the time of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. 1 of 21 subjects receiving 3rd generation tyrosine kinase-inhibitor (TKI) developed COVID-19 versus 3 of 346 subjects receiving imatinib versus 0 of 162 subjects receiving 2nd generation TKIs (P = 0.096). Other co-variates such as age and TKI-therapy duration were not significantly associated with an increased risk of developing COVID-19. Persons with these risk factors may benefit from increased surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 infection and possible protective isolation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some data suggest persons with cancer are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2-infection and to develop coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) compared with normals (1% [95% Confidence Interval (CI), 0.6, 1.7%] versus 0.1% [0, 0.12%]), but these estimates are controversial and it is unclear if this increased risk applies to persons with all cancer types [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. One study of 125 hospitalised persons with haematological cancers had a 10 percent (6, 17%) case rate of COVID-19 but none of their subjects had chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) [9]. We performed a cross-sectional survey of non-hospitalized persons with CML receiving tyrosine kinase-inhibitor (TKI)-therapy in Hubei Province to explore the prevalence and clinical features of COVID-19 during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Prevalence of COVID-19 in persons with CML, 0.9 percent (0.1, 1.8%) was substantially higher than normals but lower than hospitalised persons with haematological cancers. Clinical features of COVID-19 in our subjects and otherwise normal persons were similar. We identified co-variates associated with an increased risk of developing COVID-19. Persons with these co-variates may benefit from increased SARS-CoV-2-infection surveillance and possible protective isolation.

Methods

Survey design

From February 15, 2020 to April 10, 2020 persons with CML receiving TKI-therapy from Hubei Province were recruited from 29 centres of the Hubei Anti-Cancer Association. An online questionnaire was distributed and collected by physicians at each centre. Persons with CML or their family (if they were too sick or died) were asked to complete the questionnaire which included two dimensions (Supplementary 1). The 1st included 16 questions assessing demographics, co-morbidities, CML-related data including diagnosis, therapy and response. The 2nd included 12 questions related to COVID-19 including exposure history, symptoms of acute respiratory illness such as fever, cough, shortness of breath and fatigue, diagnosis, treatment and outcome. Missing or unclear data items were collected and clarified by direct communication between physicians and the patient, their family and/or health-care providers. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College who waived the requirement for written informed consent. Data were analyzed as of Aril 11, 2020.

Diagnosis, monitoring and response to TKI-therapy of CML

Diagnosis, disease phase, monitoring and response to TKI-therapy were based on European LeukemiaNet recommendations [10].

Diagnosis, severity and outcome of COVID-19

Infection was confirmed by qualitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 was diagnosed according to the World Health Organisation criteria (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331506/WHO-2019-nCoV-SurveillanceGuidance-2020.6-eng.pdf). Severity of COVID-19 was graded as follows (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml): (1) mild–mild clinical symptoms, no pneumonia on lung CT scan; (2) common-fever, cough and lung CT with pneumonia; (3) severe-respiratory distress (respiratory rate > 30/min, oxygen saturation (O2Sat) ≤ 93% at rest and/or ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen ≤300 mmHg (PaO2/FIO2); and (4) critical-criteria of respiratory failure and mechanical ventilation, shock, organ failure (other than lung) and/or intensive care unit hospitalisation. Therapy of COVID-19 was according to the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Prevention and Control Programme of the National Health Commission of China (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml).

Outcomes other than death were defined as follows: (1) cure—two successive negative RT-PCR tests >24 h apart and asymptomatic; (2) improved—improvement in signs, symptoms, and laboratory parameters and no progression on lung CT scan; (3) progressing—increase in symptoms and/or progression of lung CT scan findings; (4) stable—not progressing or improving (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis results are presented as median (range) or number (percentage) as appropriate. Pearson Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U/Kruskal–Wallis tests (for continuous variables) were used to measure between-group differences. Variables with P < 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were conducted with SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Subject variables

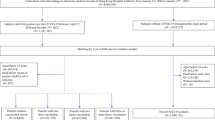

Among 551 persons with CML receiving TKI-therapy in the Hubei Anti-Cancer Association, 476 filled out electronic questionnaires. Another 75 were completed telephonically by health-care providers. Questionnaires from 21 subjects not resident in Hubei Province during the outbreak were excluded. Data from 530 subjects were included in this report. Two hundred and ninety-six (56%) were male. Median age was 44 years (range, 6–89 years). Ninety-five (18%) were ≥60 years. One hundred and forty (26%) had ≥1 co-morbidity(ies). Five hundred and nineteen (98%) were in the chronic phase (CP) at diagnosis of CML. One subject was synchronously diagnosed with CML by RT-PCR and COVID-19. 346 (65%) were receiving imatinib when they answered the questionnaire, 102 (19%), dasatinib; 59 (11%), nilotinib; 18, HQP1351 (a 3rd generation TKI under study in a clinical trial); 3, ponatinib; and 2, flumatinib (a new 2nd generation TKI developed in China). Median TKI-therapy duration was 42 months (range, 1–182 months). All 530 were in the CP when they answered the questionnaire. Eighty-one (15%) had a complete haematologic response (CHR); 52 (10%), a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR); and 387 (73%), a major molecular response (MMR).

All 530 subjects continued resident in Hubei Province during the epidemic. Four reported close contact with SARS-CoV-2 infected persons. Eighteen subjects had an acute respiratory illness including fever (n = 8), cough (n = 7), sore throat (n = 4), fatigue (n = 3), and shortness of breath (n = 2). Eleven had mild symptoms, were isolated at home and recovered within 2–4 days. Seven others had moderate or severe illness and were hospitalised. Two subjects with a negative qRT-PCR for SARS-CoV-19 and no abnormality of lung CT scan were excluded. Four subjects had confirmed COVID-19. One subject was classified as probable COVID-19 because of no qRT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 testing. Cumulative prevalence of confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases was 0.9 percent (0.1, 1.8%).

Comparison of baseline co-variates of the subjects with and without COVID-19

Baseline co-variates of subjects with (n = 5) and without COVID-19 (n = 525) are shown in Table 1. Subjects with COVID-19 were more likely to have been in the accelerated or blast phase at diagnosis (2 of 5 versus 2%; P = 0.004), no CHR at diagnosis of COVID-19 (2 of 5 versus 2%; P = 0.003), have ≥1 co-morbidity(ies) (4 of 5 versus 26%; P = 0.024) and have contact with confirmed or suspected persons (1 of 5 versus 0.6%, P = 0.037). 1 of 21 (5%) subjects receiving 3rd generation TKI developed COVID-19 versus 3 of 346 (1%) subjects receiving imatinib versus 0 of 162 subjects receiving 2nd generation TKIs, P = 0.095). There was no difference between the cohorts in sex, age and TKI-therapy duration.

Clinical features and outcomes of the subjects with COVID-19

Clinical features and outcomes of the five subjects with confirmed or probable COVID-19 are summarised in Table 2 and Supplementary 2. Four subjects with confirmed mild (N = 1) or common (n = 3) COVID-19 had typical symptoms and/or lung CT scan findings; all recovered. An older female subject (case 5) with probable critical severe COVID-19 had typical lung CT scan findings (Fig. 1) and developed ARDS. Her condition deteriorated rapidly and she died of multiple organ failure. Four subjects remained on TKI-therapy during COVID-19 treatment.

Discussion

Whether persons with CML are immune compromised is controversial [11]. However, TKI-therapy is immune suppressive [12,13,14]. Based on these data one might expect a higher incidence and prevalence of SARS-CoV-2-infection and higher case- and case-fatality rates of COVID-19 in persons with CML compared with normals. We found a 0.9 percent prevalence of COVID-19 in persons with CML receiving TKI-therapy in Hubei Provence, ninefold higher than the reported 0.1 percent (0.11, 0.12%) incidence by April 10, 2020 in the general population (http://en.nhc.gov.cn/2020-04/11/c_79032.htm). Clinical features of the confirmed COVID-19 in our survey were like that reported in Hubei Province [15,16,17]. One subject died but our sample size is too small to compare with the published case-fatality rate of about 4% [18, 19].

We found several co-variates associated with an increased risk to develop COVID-19. Including exposure to someone infected with SARS-CoV-2, no CHR and co-morbidity(ies). There was also an increased risk of developing COVID-19 in subjects in advanced phase CML at diagnosis even when they achieved a CCyR or MMR at the time of the pandemic. One of 21 subjects receiving 3rd generation TKIs developed COVID-19 compared with 3 of 346 subjects receiving imatinib and none of 162 subjects receiving 2nd generation TKIs (P = 0.096). These data suggest possibly different risks but need confirmation. There are no data whether 3rd generation TKI is more immune suppressive than other TKIs. Also, 1 of 2 subjects receiving flumatinib developed COVID-19. However, one subject had synchronous diagnoses of CML and COVID-19 excluding a causative. Why subjects with advanced leukaemia at diagnosis had a higher risk of COVID-19 despite responding well to TKI-therapy is unclear.

There are several limitations to our study. First, there were selection biases. Because the survey was made available online, respondents were self-selected. These persons had computer access and competence and tended to be proactive in seeking information and resources for their care. As such, the likelihood of detecting SARS-CoV-2-infection and COVID-19 is higher than in the general Hubei population. Second, not all 18 subjects with acute respiratory illness were tested for SARS-CoV-19-infection so our prevalence estimate may be an under-estimate. However, according to Chinese government policy, people with mild illness were isolated at home and not tested for SARS-CoV-2-infection. Eleven of these 18 had no lung CT scan we may have under-estimated the prevalence of COVID-19 in our sample.

In summary, our survey suggests that although persons with CML receiving TKI-therapy developing COVID-19 may be higher than the general population the absolute case-rate is very low and clinical features are like normals. Persons with no CHR, with co-morbidity(ies), with advanced phase at diagnosis despite responding to TKI-therapy and those exposed to someone with SARS-CoV-2-infection may benefit from increased surveillance and possible protective isolation

References

Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–7.

Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, Wang C, Wang J, Chen R, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: A retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020:S0923-7534(20)36383-3.

Xia Y, Jin R, Zhao J, Li W, Shen H. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e180.

Wang H, Zhang L. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e181.

Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980.

Kutikov A, Weinberg DS, Edelman MJ, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Fisher RI. A war on two fronts: cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1133.

The Lancet Oncology. COVID-19: global consequences for oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:467.

Lilienfeld-Toal M, Vehreschild JJ, Cornely O, Pagano L, Compagno F, EHA Infectious Disease Scientific Working Group, et al. Frequently asked questions regarding SARS-CoV2 in cancer patients—recommendations for clinicians caring for patients with malignant diseases. Leukemia. 2020. In press.

He W, Chen L, Chen L, Yuan G, Fang Y, Chen W, et al. COVID-19 in persons with haematological cancers. Leukemia. 2020;1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0836-7.

Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, Schiffer C, Apperley JF, Cervantes F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:966–84.

Gale RP, Opelz G. Is there immune surveillance against chronic myeloid leukaemia? Possibly, but not much. Leuk Res. 2017;57:109–11.

Weichsel R, Dix C, Wooldridge L, Clement M, Fenton-May A, Sewell AK, et al. Profound inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell effector functions by dasatinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2484–91.

Thiant S, Moutuou MM, Laflamme P, Sidi Boumedine R, Leboeuf DM, Busque L, et al. Imatinib mesylate inhibits STAT5 phosphorylation in response to IL-7 and promotes T cell lymphopenia in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e551.

Dörfel D, Lechner CJ, Joas S, Funk T, Gutknecht M, Salih J, et al. The BCR-ABL inhibitor nilotinib influences phenotype and function of monocyte-derived human dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:775–83.

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72/314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

Spychalski P, Błażyńska-Spychalska A, Kobiela J. Estimating case fatality rates of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020:S1473-3099(20)30246–2.

Acknowledgements

We thank patients, families and physicians from Hubei Anti-Cancer Association (XLZ, DZJ, HXW, JH, YFZ, BC, QW, ZPH, QHL, YB, DLZ, XHZ, ZZ, RYG, JD, YPW, HBR, HH, YHW, and HX) who participated in the study. This study is funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81873440, 81770161, and 81700142). RPG acknowledges support from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Hubei Anti-Cancer Association

Yicheng Zhang9, Weiming Li1, Yang Chao9, Jingming Guo3, Guolin Yuan4, Zhuangzhi Yang5, Shiming Chen7, Chucheng Wan8, Wei Chang10, Hui Cheng11, Youshan Zhang12, Jun Qin13, Xuelan Zuo15, Daozi Jiang16, Hongxiang Wang17, Jun Huang18, Youfang Zhao19, Bin Chen20, Qing Wu21, Zhiping Huang22, Qihuan Liu23, Ying Bao24, Dalin Zhang25, Xinhua Zhang26, Zhe Zhao27, Renying Ge28, Jie Du29, Hongbo Ren12, Hong Han30, Yunhui Wei31, Hang Xiang32

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

WML, QJ, LM designed the study. DYW, JMG, GLY, ZZY, YY, ZCC, SMC, CCW, XJZ, WC, LSS, HC, YSZ, QL, and JQ, collected the data. WML, QJ and RPG analyzed the data and help prepare the typescript. All authors approved final approval and supported submission for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the Hubei Anti-Cancer Association are listed below acknowledgement.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Wang, D., Guo, J. et al. COVID-19 in persons with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 34, 1799–1804 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0853-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0853-6

This article is cited by

-

The impact of Covid-19 in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia—a nationwide population-based study

Leukemia (2023)

-

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5.2-infection and COVID-19 in persons with chronic myeloid leukaemia

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and coronavirus disease 2019 in the Omicron era

Annals of Hematology (2023)

-

Improving safety in dental practices during the COVID-19 pandemic

Health and Technology (2022)

-

What Do We Currently Know About Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) and COVID-19?

Current Oncology Reports (2022)