Abstract

Objective

Measure the effectiveness of and preference for a standardized, national curriculum utilizing flipped classrooms (FC) in neonatal-perinatal medicine (NPM) fellowships.

Study design

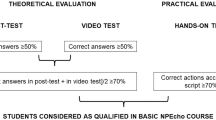

Multicentered equivalence, cluster randomized controlled trial of NPM fellowship programs randomized to receive standardized physiology education as in-class lectures (traditional didactic, TD arm) or as pre-class online videos followed by in-class discussions (FC arm). Four multiple-choice question quizzes and three surveys were administered to measure knowledge acquisition, retention, and educational preferences.

Results

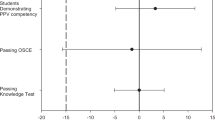

530 fellows from 61 NPM fellowships participated. Quiz performance was comparable between groups at all time points (p = NS, TD vs FC at 4 time points). Post intervention, more fellows in both groups preferred group discussions (pre/post FC 42% vs. 58%, P = 0.002; pre/post TD 43% vs. 60%, P = < 0.001). FC fellows were more likely to rate classroom effectiveness positively (FC/TD, 70% vs. 36%, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

FCs promote knowledge acquisition and retention equivalent to TD and FC modalities are preferred by fellows.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Datasets and other supporting materials will be made available to readers promptly upon request.

References

Ryan RMDE. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-bein. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78.

Ten Cate O, Kusurkar RA, Williams GC. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE Guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2012;33:961–73.

Phillips J, Wiesbauer F. The flipped classroom in medical education: A new standard in teaching. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2022;42:4–8.

Chen F, Lui AM, Martinelli SM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ. 2017;51:585–97.

French H, Arias-Shah A, Gisondo C, Gray MM. Perspectives: the flipped classroom in graduate medical education. Neoreviews. 2020;21:e150–6.

Blair RA, Caton JB, Hamnvik OR. A flipped classroom in graduate medical education. Clin Teach. 2020;17:195–9.

Lin Y, Zhu Y, Chen C, Wang W, Chen T, Li T, et al. Facing the challenges in ophthalmology clerkship teaching: Is flipped classroom the answer? Plos One. 2017;12:e0174829.

Martinelli SM, Chen F, DiLorenzo AN, Mayer DC, Fairbanks S, Moran K, et al. Results of a flipped classroom teaching approach in anesthesiology residents. J Graduate Med Educ. 2017;9:485–90.

Tainter CR, Wong NL, Cudemus-Deseda GA, Bittner EA. The “flipped classroom” model for teaching in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2016;32:187–96.

Marchalot A, Dureuil B, Veber B, Fellahi JL, Hanouz JL, Dupont H, et al. Effectiveness of a blended learning course and flipped classroom in first year anaesthesia training. Anaesth Crit Care Pa. 2018;37:411–5.

Riddell J, Jhun P, Fung CC, Comes J, Sawtelle S, Tabatabai R, et al. Does the flipped classroom improve learning in graduate. Med Educ? J Graduate Med Educ. 2017;9:491–6.

Graham KLCA, Reynolds EE, Huang GC. Effect of a flipped classroom on knowledge acquisition and retention in an internal medicine residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:92–7.

French H, Gray M, Gillam-Krakauer M, Bonachea EM, Carbajal M, Payne A, et al. Flipping the classroom: a national pilot curriculum for physiology in neonatal–perinatal medicine. J Perinatol. 2018;38:1420–7.

Izatt S, Gray M, Dadiz R, French H. Development and implementation of a national neonatology flipped classroom curriculum. J Graduate Med Educ. 2019;11:335–6.

Gray M, Dadiz R, Izatt S, Gillam-Krakauer M, Carbajal MM, Falck AJ, et al. Value, strengths, and challenges of e-learning modules paired with the flipped classroom for graduate medical education: a survey from the national neonatology curriculum. Am J Perinat. 2020;38:e187–92.

American Board of Pediatrics. Content Outline: Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/pdf/neonatal_perinatal_content_outline.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2018.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42:377–81.

McConnell MMMS, Bryson GL. Sample size calculations for educational interventions: principles and methods. Can J Anesth. 2019;66:864–73.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

Vaona A, Banzi R, Kwag KH, Rigon G, Cereda D, Pecoraro V, et al. E‐learning for health professionals. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD011736.

Hew KF, Lo CK. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. Bmc Med Educ. 2018;18:38.

Evans L, Vanden Bosch ML, Harrington S, Schoofs N, Coviak C. Flipping the classroom in health care. High Educ Nurs Educ. 2019;44:74–8.

Rui Z, Lian-rui X, Rong-zheng Y, Jing Z, Xue-hong W, Chuan Z. Friend or foe? Flipped classroom for undergraduate electrocardiogram learning: a randomized controlled study. Bmc Med Educ. 2017;17:53.

Prithishkumar I, Michael S. Understanding your student: Using the VARK model. J Postgrad Med. 2014;60:183–6.

Rogers L, Cohen MS. Medical education in pediatric and congenital heart disease: a focus on generational learning and technology in education. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2020;59:101305.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the AAP’s Section of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine for their funding of the National Neonatology Curriculum and this research project. We also thank NPM fellowship programs, fellows, and educators who participated in the study for their time and Med Ed On the Go for their support of this project.

Funding

This research was supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Strategic Aims Grant. The AAP was not involved in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG, HF, RD, SI, MGK, EB, MV, AP, PC, HK, LJ, MC, and AF contributed to the conception and design of the study and data collection instruments. HF and MG were involved in the recruitment of participants. MG, HF, RD, SI, MGK, EB, MV, AP, PC, HK, LJ, MC, and AF were involved in data collection. MG, MH, and HF performed data analysis. All authors (MG, HF, RD, SI, MGK, EB, MV, AP, PC, HK, LJ, MC, AF, MH) contributed to the interpretation of the data. HF, MG, RD, and SI prepared the initial draft manuscript. MG, HF, RD, SI, MGK, EB, MV, AP, PC, HK, LJ, MC, and AF were involved in the revision and edit of the manuscript. All authors (MG, HF, RD, SI, MGK, EB, MV, AP, PC, HK, LJ, MC, AF, MH) approved of the final version to be published and are responsible for accuracy and integrity of all aspects of research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, M.M., Dadiz, R., Izatt, S. et al. Comparison of knowledge acquisition and retention following traditional didactic vs. flipped classroom education utilizing a standardized national curriculum: a randomized controlled trial. J Perinatol 42, 1512–1518 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-022-01423-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-022-01423-4