Abstract

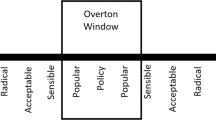

Critical decision-making in neonatology and other areas of pediatrics often carries with it a complex and difficult ethical component. For any treatment under consideration, the impermissible–permissible–obligatory (I–P–O) spectrum provides a useful framework for determining how to proceed. Any proposed treatment can be located along this spectrum, and identified as either ethically impermissible, permissible, or obligatory. Treatments determined to be ethically impermissible should not be made available by physicians. Those deemed ethically permissible should be explained to parents, commonly with a specific recommendation. Informed parents should then be free to choose from among permissible options. Potential treatments deemed ethically obligatory should be provided to the patient, even in the face of parental objection. The fundamental ethical work in neonatology and pediatrics is determining where on the I–P–O spectrum a treatment under consideration should be located. This should be determined by the prognosis for the patient with and without the treatment, the feasibility of providing the treatment, and consideration of all relevant rights and obligations. Location on the line is dynamic, and clinicians should be open to movement of a given treatment along the spectrum as new information, particularly regarding effectiveness, toxicity, and/or alternatives, becomes available. This framework provides a structure for ethical conversation and decision-making related to a specific patient, as well as in the formation of institutional and national guidelines.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Feudtner C, Schall T, Hill D. Parental personal sense of duty as a foundation of pediatric medical decision-making. Pediatrics. 2018;142:S133–41.

Sullivan A, Cummings C. Historical perspectives: shared decision making in the NICU. NeoReviews. 2020;21:e217–25.

Lantos JD. Ethical problems in decision making in the neonatal ICU. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1851–60.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement: religious objections to medical care. Pediatrics. 1997;99:279–81. Reaffirmed Oct 2006.

Weiner GM, Zaichkin J, Kattwinkel J, Eds. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation (NRP), 7th edition. Lesson 11: Ethics and Care at the End of Life. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association. 2016:265–75.

Cummings J, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Antenatal counseling regarding resuscitation and intensive care before 25 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics . 2015;136:588–59.

Mercurio MR. The ethics of newborn resuscitation. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:354–63.

Cummings C, Mercurio M. Ethics of emerging technologies and their transition to accepted practice: intestinal transplant for short bowel syndrome. J Perinatol. 2012;32:752–6.

Marathe SP, Talwar S. Surgery for transposition of great arteries: a historical perspective. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;8:122–8.

Hartnett ME, Lane RH. Effects of oxygen on the development and severity of retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS. 2013;17:229–34.

Cummings CL, Diefenbach K, Mercurio M. Counseling and practice variation among physicians regarding intestinal transplant for severe short bowel syndrome. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:665–70.

Truog RD, Brett AS, Frader J. The problem with futility. NEJM. 1992;326:1560–4.

Helft PR, Siegler M, Lantos J. The rise and fall of the futility movement. NEJM. 2000;343:293–6.

Cummings C, Mercurio M. Ethics for the pediatrician: autonomy, beneficence and rights. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31:252–5.

Mercurio MR, Murray PD, Gross I. Unilateral pediatric “do not attempt resuscitation” orders: the pros, the cons, and a proposed approach. Pediatrics. 2014;133:S37–43.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of bioethics. 7th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Hardwig J. What about the family? Hastings Cent Rep. 1990;20:5–10.

Chapman RL, Peterec SM, Bizzarro MJ, Mercurio MR. Patient selection for neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: beyond severity of illness. J Perinatol. 2009;29:606–11.

DeTora A, Cummings CL. Ethics and the law: practical applications in the NICU. Neoreviews. 2015;16:e384–92.

Janvier A, Mercurio MR. Saving vs creating: perceptions of intensive care at different ages and the potential for injustice. J Perinatol. 2013;33:333–35.

Haward M, Mercurio M, Janvier A. Perpetuating biases and injustice toward preterm infants. Am J Bioeth. 2017;17:27–29.

Rhodes R, Holzman IR. Is the best interest standard good for pediatrics? Pediatrics. 2014;134:S121–2.

Gillam L. The zone of parental discretion: an ethical tool for dealing with disagreement between parents and doctors about medical treatment for a child. Clin Ethics. 2016;11:1–8.

Funding Information

CLC is supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award R01HD094794 (CC PI). MRM is supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health 5R25TW007700.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MRM participated in the development of the concepts and framework, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and participated in the revision of the manuscript. CLC participated in the development of the concepts and framework, and participated in the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CLC has no conflicts of interest to disclose. MRM receives royalty payments as a contributor to the online publication Up-To-Date.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mercurio, M.R., Cummings, C.L. Critical decision-making in neonatology and pediatrics: the I–P–O framework. J Perinatol 41, 173–178 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-00841-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-00841-6

This article is cited by

-

Navigating the post-Dobbs landscape: ethical considerations from a perinatal perspective

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

The patient/physician relationship in a post-Roe world: a neonatologist viewpoint

Journal of Perinatology (2023)

-

The past, current, and future of neonatal intensive care units with artificial intelligence: a systematic review

npj Digital Medicine (2023)

-

Resuscitation policies for extremely preterm newborns: finally moving beyond gestational age

Journal of Perinatology (2020)