Abstract

Objective

To quantify racial differences in contribution of previable live births (<20 weeks gestational age (GA)) to United States (US) Infant Mortality Rates (IMR).

Methods

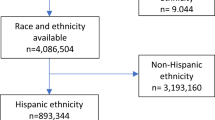

Population-based retrospective cohort of US live births (2007–14) using CDC WONDER database stratified by maternal race/ethnicity. We compared the contribution of previable births to IMR and calculated modified IMRs (≥20 weeks GA) excluding previable live births in each group. Contingency tables and chi-square calculations were performed to detect differences between groups.

Results

Previable deaths represented 4.1%, 7.7%, and 5.0% of total deaths for nonHispanic white, nonHispanic black, and Hispanic, respectively. Previable contribution to total IMR are 0.21, 0.89, and 0.26 per 1000 live births (P < 0.0001). Modified IMRs are 4.98, 10.85, and 4.69 deaths per 1000 live births.

Conclusion

IMR standardization with a minimum GA may obscure the disproportionate contribution of previable births to IMRs among the black population, which has the largest proportion of previable births.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1–30.

Willis E, McManus P, Magallanes N, Johnson S, Majnik A. Conquering racial disparities in perinatal outcomes. Clin Perinatol. 2014;41:847–75.

MacDorman MF, Mathews TJ. Understanding racial and ethnic disparities in US infant mortality rates. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;74:1–8.

MacDorman MF. Race and ethnic disparities in fetal mortality, preterm birth, and infant mortality in the United States: an overview. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35:200–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC features: premature birth. https://www.cdc.gov/features/prematurebirth/index.html. Accessed 5 July 2018.

Eikemo TA, Skalicka V, Avendano M. Variations in relative health inequalities: are they a mathematical artefact? Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:32.

March of dimes 2017 premature birth report card. https://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/PrematureBirthReportCard-United-States-2017.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2018.

DeFranco EA, Hall ES, Muglia LJ. Racial disparity in previable birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:394 e391–397.

American College of O, Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal M. Obstetric care consensus no. 6: periviable birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e187–e199.

Barfield WD, Committee On F, Newborn. Standard terminology for fetal, infant, and perinatal deaths. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20160551.

Silver RM, Branch DW, Goldenberg R, Iams JD, Klebanoff MA. Nomenclature for pregnancy outcomes: time for a change. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1402–8.

Lee ML, Hall E, Taylor M, DeFranco E. Contribution of previable infant deaths to infant mortality rates among US census regions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:S444–S445.

Malloy MH. The Born-Alive Infant Protection Act: impact on fetal and live birth mortality. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:399–404.

Stampfel C, Kroelinger CD, Dudgeon M, Goodman D, Ramos LR, Barfield WD. Developing a standard approach to examine infant mortality: findings from the State Infant Mortality Collaborative (SIMC). Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(Suppl 2):360–9.

Williams BL, Magsumbol MS. Inclusion of non-viable neonates in the birth record and its impact on infant mortality rates in Shelby County, Tennessee, USA. Pedia Rep. 2010;2:e1.

United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Division of Vital Statistics (DVS). Linked birth/infant death records 2007–2015, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program, on CDC WONDER on-line database. https://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd-current.html. Accessed 18 Feb 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive health; maternal and infant health: infant mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm. Accessed 5 July 2018.

Larsen EC, Christiansen OB, Kolte AM, Macklon N. New insights into mechanisms behind miscarriage. BMC Med. 2013;11:154.

Moutquin JM. Classification and heterogeneity of preterm birth. BJOG. 2003;110(Suppl 20):30–33.

National Center for Health Statistics Guide to completing the facility worksheets for the certificate of live birth and report of fetal death (2003 revision). Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/GuidetoCompleteFacilityWks.pdf Accessed 9 Mar 2019.

U.S. Standard Certificate of Live Birth (November 2003). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/birth11-03final-ACC.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2019.

VassarStats: Lowry, R. Chi-Square, Cramer’s V, Lambda. http://vassarstats.net/newcs.html. Accessed 18 Feb 2018.

Mukherjee S, Velez Edwards DR, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Hartmann KE. Risk of miscarriage among black women and white women in a US prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1271–8.

Chen HY, Chauhan SP, Rankins NC, Ananth CV, Siddiqui DS, Vintzileos AM. Racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality in the United States: the role of gestational age. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:469–75.

Loggins S, Andrade FC. Despite an overall decline in US infant mortality rates, the black/white disparity persists: recent trends and future projections. J Community Health. 2014;39:118–23.

Hall ES, Lee M, DeFranco EA. Contribution of previable live births to disparity in infant mortality of US-born Puerto Ricans compared with infants of other Hispanic origins. Public Health. 2018;160:77–80.

Funding

ML received research funding from an educational grant from the University of Cincinnati, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Women’s Health Scholars Program at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. ED received research funding from the Perinatal Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center Ohio Collaborative

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Presentation information

The abstract for this study was presented at the 2018 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting (poster presentation), April 27–30, 2018, Austin, TX

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, M., Hall, E.S. & DeFranco, E. Contribution of previable births to infant mortality rate racial disparity in the United States. J Perinatol 39, 1190–1195 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0394-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0394-x

This article is cited by

-

Cohort selection and the estimation of racial disparity in mortality of extremely preterm neonates

Pediatric Research (2023)