Abstract

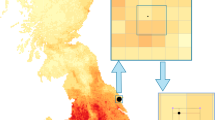

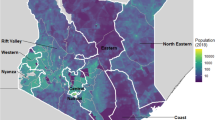

Health studies on spatially-varying exposures (e.g., air pollution) during pregnancy often estimate exposure using residence at birth, disregarding residential mobility. We investigated moving patterns in pregnant women (n = 10,116) in linked cohorts focused on Connecticut and Massachusetts, U.S., 1988–2008. Moving patterns were assessed by race/ethnicity, age, marital status, education, working status, population density, parity, income, and season of birth. In this population, 11.6% of women moved during pregnancy. Movers were more likely to be younger, unmarried, and living in urban areas with no previous children. Among movers, multiple moves were more likely for racial/ethnic minority, younger, less educated, unmarried, and lower income women. Most moves occurred later in pregnancy, with 87.4% of first moves in the second or third trimester, although not all cohort subjects enrolled in the first few weeks of pregnancy. Distance between first and second residence had a median value of 5.2 km (interquartile range 11.3 km, average 57.8 km, range 0.0–4277 km). Women moving larger distances were more likely to be white, older, married, and work during pregnancy. Findings indicate that residential mobility may impact studies of spatially-varying exposure during pregnancy and health and that subpopulations vary in probability of moving, and timing and distance of moves.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wilhelm M, Ghosh JK, Su J, Cockburn M, Jerrett M, Ritz B. Traffic-related air toxics and preterm birth: a population-based case-control study in Los Angeles county, California. Environ Health. 2011;10:Art. No. 89.

Bell ML, Ebisu K, Belanger K. Ambient air pollution and low birth weight in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1118–25.

Ahern M, Mullett M, Mackay K, Hamilton C. Residence in coal-mining areas and low-birth-weight outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:974–9.

Winchester PD, Huskins J, Ying J. Agrichemicals in surface water and birth defects in the United States. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:664–9.

Auger N, Joseph D, Goneau M, Daniel M. The relationship between residential proximity to extremely low frequency power transmission lines and adverse birth outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:83–5.

Brender JD, Shinde MU, Zhan FB, Gong X, Langlois PH. Maternal residential proximity to chlorinated solvent emissions and birth defects in offspring: a case-control study. Environ Health. 2014;13:96.

Porter TR, Kent ST, Su W, Beck HM, Gohlke JM. Spatiotemporal association between birth outcomes and coke production and steel making facilities in Alabama, USA: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2014;13:85.

Dadvand P, et al. Residential proximity to major roads and term low birth weight: the roles of air pollution, heat, noise, and road-adjacent trees. Epidemiology. 2014;25:518–25.

McKenzie LM, Guo R, Witter RZ, Savitz DA, Newman LS, Adgate JL. Birth outcomes and maternal residential proximity to natural gas development in rural Colorado. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:412–7.

Huppe V, Kestens Y, Auger N, Daniel M, Smargiassi A. Residential proximity to gasoline service stations and preterm birth. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013;20:7186–93.

Gemmill A, Gunier RB, Bradman A, Eskenazi B, Harley KG. Residential proximity to methyl bromide use and birth outcomes in an agricultural population in California. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:737–43.

Wang SI, Lee LT, Zou ML, Fan CW, Yaung CL. Pregnancy outcome of women in the vicinity of nuclear power plants in Taiwan. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2010;49:57–65.

Langlois PH, et al. Maternal residential proximity to waste sites and industrial facilities and conotruncal heart defects in offspring. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:321–31.

Bell ML, Belanger K. Review of research on residential mobility during pregnancy: consequences for assessment of prenatal environmental exposures. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22:429–38.

Blaasaas KG, Tynes T, Lie RT. Residence near power lines and the risk of birth defects. Epidemiology. 2003;14:95–98.

Brauer M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, Koehoorn M, Demers P, Karr C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:680–6.

Hodgson S, Lurz PW, Shirley MD, Bythell M, Rankin J. Exposure misclassification due to residential mobility during pregnancy. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2015;218:414–21.

Sadler L, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and small-for-gestational-age birth. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:695–705.

Grosso LM, Triche EW, Belanger K, Benowitz NL, Holford TR, Bracken MB. Caffeine metabolites in umbilical cord blood, cytochrome P-450 1A2 activity, and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1035–41.

Bracken MB, Triche EW, Belanger K, Hellenbrand K, Leaderer BP. Association of maternal caffeine consumption with decrements in fetal growth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:456–66.

Bracken MB, Triche E, Grosso L, Hellenbrand K, Belanger K, Leaderer BP. Heterogeneity in assessing self-reports of caffeine exposure: implications for studies of health effects. Epidemiology. 2002;13:165–71.

Triche EW, Saftlas AF, Belanger K, Leaderer BP, Bracken MB. Association of asthma diagnosis, severity, symptoms, and treatment with risk of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:585–93.

Belanger K, Hellenbrand ME, Holford TR, Bracken M. Effect of pregnancy on maternal asthma symptoms and medication use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:559–67.

Triche EW, et al. Indoor heating sources and respiratory symptoms in nonsmoking women. Epidemiology. 2005;16:377–84.

Rogal SS, et al. Effects of posttraumatic stress disorder on pregnancy outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:137–43.

Spoozak L, Gotman N, Smith MV, Belanger K, Yonkers KA. Evaluation of a social support measure that may indicate risk of depression during pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:216–23.

Bryere J, Pornet C, Dejardin O, Launay L, Guittet L, Launoy G. Correction of misclassification bias induced by the residential mobility in studies examining the link between socioeconomic environment and cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:256–64.

Drevdahl DJ, Philips DA, Taylor JY. Uncontested categories: the use of race and ethnicity variables in nursing research. Nurs Inq. 2006;13:52–63.

Valles SA, Bhopal RS, Aspinall PJ. Census categories for mixed race and mixed ethnicity: impacts on data collection and analysis in the US, UK and NZ. Public Health. 2015;129:266–70.

Ito K, Xue N, Thurston G. Spatial variation of PM2.5 chemical species and source-apportioned mass concentrations in New York City. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:5269–82.

Bravo MA, Bell ML. Spatial heterogeneity of PM10 and O3 in São Paulo, Brazil, and implications for human health studies. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2011;61:69–77.

Hu XF, Du Y, Feng JW, Fang SQ, Gao XJ, Xu SY. Spatial and seasonal variations of heavy metals in wetland soils of the tidal flats in the Yangtze Estuary, China: environmental implications. Pedosphere. 2013;23:511–22.

Rice J, Westerhoff P. Spatial and temporal variation in de facto wastewater reuse in drinking water systems across the U.S.A. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:982–9.

Boyle PJ, Kulu H, Cooke T, Gayle V, Mulder CH. Moving and union dissolution. Demography. 2008;45:209–22.

Brown D, Benzeval M, Gayle V, Macintyre S, O’Reilly D, Leyland AH. Childhood residential mobility and health in late adolescence and adulthood: findings from the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:942–50.

Busacker A, Kasehagen L. Association of residential mobility with child health: an analysis of the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(Suppl 1):S78–87.

Jelleyman T, Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:584–92.

Haelermans C, De Witte K. Does residential mobility improve educational outcomes? Evidence from the Netherlands. Soc Sci Res. 2015;52:351–69.

Jackson N, Denny S, Ameratunga S. Social and socio-demographic neighborhood effects on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of multi-level studies. Soc Sci Med. 2014;115:10–20.

Hendershott AB. Residential mobility, social support and adolescent self-concept. Adolescence. 1989;24:217–32.

Oishi S, Schimmack U. Residential mobility, well-being, and mortality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:980–94.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Yale Center for Perinatal, Pediatric, and Environmental Epidemiology and study participants. This work was funded by NIEHS (R01ES01587 and R01ES019560), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA RD 83479801 and RD 835871) and an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship grant (1052236 to GP). This paper has not been formally reviewed by the EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Agency. EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bell, M.L., Banerjee, G. & Pereira, G. Residential mobility of pregnant women and implications for assessment of spatially-varying environmental exposures. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 28, 470–480 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-018-0026-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-018-0026-0

Key words

This article is cited by

-

Predictors of early life residential mobility in urban and rural Pennsylvania children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and implications for environmental exposure assessment

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2023)

-

Assessing Exposure to Unconventional Oil and Gas Development: Strengths, Challenges, and Implications for Epidemiologic Research

Current Environmental Health Reports (2022)

-

On the potential of iPhone significant location data to characterize individual mobility for air pollution health studies

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2022)