Abstract

Background

Current knowledge regarding the relationship between segregation and body weight is derived mainly from cross-sectional data. Longitudinal studies are needed to provide stronger causal inference.

Methods

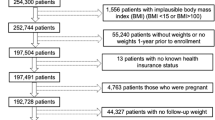

We use longitudinal data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and apply an econometric fixed-effect strategy, which accounts for all time-invariant confounders, and compare results to conventional cross-sectional analyses. We examine the relationship between neighborhood-level racial/ethnic segregation, neighborhood poverty, and body mass index (BMI) separately for blacks, Hispanics, and whites. Segregation*gender interactions are included in all models. Neighborhood segregation was operationalized by the local Gi* statistic, which assesses the extent to which a neighborhood’s racial/ethnic composition is under (Gi* statistic < 0) or over (Gi* statistic > 0) represented, given the composition in the broader (e.g., county) area. For black, Hispanic, and white stratified models, the Gi* statistic reflects the level of black, Hispanic, and white segregation, respectively. The Gi* statistic was scaled such that a unit change represents a 1.96 difference in the score.

Results

Cross-sectional models indicated higher segregation to be negatively associated with BMI for white females and positively associated for Hispanic females. No association was found for black females or males in general. In contrast, fixed-effect models adjusting for neighborhood poverty, higher segregation was positively associated with BMI for black females (coeff = 0.25 kg/m2; 95% CI = [0.03, 0.46]; p-value = 0.03) but negatively associated for Hispanic females (coeff = −0.17 kg/m2; 95% CI = [−0.33, −0.01]; p-value = 0.04) and Hispanic males (coeff = −0.20; 95% CI = [−0.39, −0.01]; p-value = 0.04). Further controls for socioeconomic factors fully explained the associations for Hispanics but not for black females.

Conclusions

Fixed-effect results suggest that segregation’s impacts might not be universally harmful, with possible null or beneficial impacts, depending on race/ethnicity. The persistent associations after accounting for neighborhood poverty indicate that the segregation–BMI link may operate through different pathways other than neighborhood poverty.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Overweight and obesity statistics. NIH Publication no. 04-4158; 2012.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015.

Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Krueger PM. The effect of obesity on overall, circulatory disease- and diabetes-specific mortality. J Biosoc Sci. 2003;35:107–29.

Pan L, Galuska DA, Sherry B, et al. Differences in prevalence of obesity among black, white, and Hispanic adults—United States, 2006–2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:740–4.

Bruce MA, Sims M, Miller S, et al. One size fits all? Race, gender and body mass index among US adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1152.

Robert SA, Reither EN. A multilevel analysis of race, community disadvantage, and body mass index among adults in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:2421–34.

Kramer MR, Hogue CR. Is segregation bad for your health? Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:178–94.

Kershaw KN, Diez Roux AV, Burgard SA, et al. Metropolitan-level racial residential segregation and black-white disparities in hypertension. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:537–45.

Kershaw KN, Osypuk TL, Do DP, et al. Neighborhood-level racial/ethnic residential segregation and incident cardiovascular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2015;131:141.

Chang VW. Racial residential segregation and weight status among US adults. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1289–303.

Chang VW, Hillier AE, Mehta NK. Neighborhood racial isolation, disorder and obesity. Soc Forces. 2009;87:2063–92.

Do DP, Dubowitz T, Bird CE, et al. Neighborhood context and ethnicity differences in body mass index: a multilevel analysis using the NHANES III survey (1988–1994). Econ Hum Biol. 2007;5:179–203.

Mobley LR, Root ED, Finkelstein EA, et al. Environment, obesity, and cardiovascular disease risk in low-income women. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:327–32.

Osypuk TL, Diez Roux AV, Hadley C, et al. Are immigrant enclaves healthy places to live? The Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:110–20.

Portes A, Shafer S. Revisiting the enclave hypothesis: Miami twenty-five years later. Res Sociol Organ. 2007;25:157–90.

Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: a portrait. 3rd ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2006.

Logan J. Separate and unequal: The neighborhood gap for blacks and Hispanics in metropolitan America. US2010 Project Discover America in a new century; 2011.

Kirby JB, Liang L, Chen H-J, et al. Race, place, and obesity: the complex relationships among community racial/ethnic composition, individual race/ethnicity, and obesity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1572–8.

Wen M, Maloney TN. Latino residential isolation and the risk of obesity in Utah: the role of neighborhood socioeconomic, built-environmental, and subcultural context. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:1134–41.

U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: Detroit city, Michigan. 2016. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/2622000. Accessed 8 Sept 2016.

U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. 2016. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00. Accessed 8 Sept 2016.

Kershaw KN, Albrecht SS, Carnethon MR. Racial and ethnic residential segregation, the neighborhood socioeconomic environment, and obesity among Blacks and Mexican Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:299–309.

Massey D, Denton N. American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993.

Do DP, Frank R, Iceland J. Black-white metropolitan segregation and self-rated health: investigating the role of neighborhood poverty. Soc Sci Med. 2017;187:85–92.

Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, et al. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:23–9.

Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, et al. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:660–7.

Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:74–81.

Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, et al. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:7–20.

Tucker-Seeley RD, Subramanian SV, Li Y, et al. Neighborhood safety, socioeconomic status, and physical activity in older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:207–13.

Getis A, Ord JK. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr Anal. 1992;24:189–206.

Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Brown DG, et al. Association of insulin resistance with distance to wealthy areas: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:389–97.

Hajat A, Diez-Roux A, Franklin TG, et al. Socioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in daily salivary cortisol profiles: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010;35:932–43.

Allison P. Fixed effects regression models. Los Angeles: Sage; 2009.

Vaisey S, Miles A. What You can—and can’t—do with three-wave panel data. Sociol Methods Res. 2014;46:44–67.

Wooldridge JM. Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. 5th ed. South-Western: Cengage Learning; 2013.

Pool LR, Carnethon MR, Goff DCJ, et al. Longitudinal associations of neighborhood-level racial residential segregation with obesity among Blacks. Epidemiology. 2018;29:207–14.

Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:233.

Salas-Wright CP, Robles EH, Vaughn MG, et al. Toward a typology of acculturative stress: results among Hispanic immigrants in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2015;37:223–42.

Funding

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, by grants UL1-TR-000040 and UL1-TR-001079 from NCRR, by grant R01 HL071759 from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health, and by grant P60 MD002249 from National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Do, D.P., Moore, K., Barber, S. et al. Neighborhood racial/ethnic segregation and BMI: A longitudinal analysis of the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Int J Obes 43, 1601–1610 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0322-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0322-3

This article is cited by

-

Household Composition, Income, and Fast-Food Consumption among Black Women and Men

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023)

-

Current Approaches to Measuring Local Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in Population Health Studies

Current Epidemiology Reports (2023)

-

Responding to Health Disparities in Behavioral Weight Loss Interventions and COVID-19 in Black Adults: Recommendations for Health Equity

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2022)

-

The impact of long-term PM2.5 exposure on specific causes of death: exposure-response curves and effect modification among 53 million U.S. Medicare beneficiaries

Environmental Health (2020)