Abstract

Background/objectives

Hypothalamic obesity (HO) occurs in 50% of patients with the pituitary tumor craniopharyngioma (CP). Attempts have been made to predict the risk of HO based on hypothalamic (HT) damage on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but none have included volumetry. We performed qualitative and quantitative volumetric analyses of HT damage. The results were explored in relation to feeding related peptides and body fat.

Subjects/methods

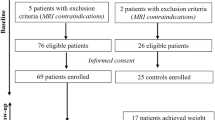

A cross-sectional study of childhood onset CPs involving 3 Tesla MRI, was performed at median 22 years after first operation; 41 CPs, median age 35 (range: 17–56), of whom 23 had HT damage, were compared to 32 controls. After exclusions, 35 patients and 31 controls remained in the MRI study. Main outcome measures were the relation of metabolic parameters to HT volume and qualitative analyses of HT damage.

Results

Metabolic parameters scored persistently very high in vascular risk particularly among HT damaged patients. Patients had smaller HT volumes compared to controls 769 (35–1168) mm3 vs. 879 (775–1086) mm3; P < 0.001. HT volume correlated negatively with fat mass and leptin among CP patients (rs = −0.67; P < .001; rs = −0.53; P = 0.001), and explained 39% of the variation in fat mass. For every 100 mm3 increase in HT volume fat mass decreased by 2.7 kg (95% CI: 1.5–3.9; P < 0.001). Qualitative assessments revealed HT damage in three out of six patients with normal volumetry, but HT damage according to operation records.

Conclusions

A decrease in HT volume was associated with an increase in fat mass and leptin. We present a method with a high inter-rater reliability (0.94) that can be applied by nonradiologists for the assessment of HT damage. The method may be valuable in the risk assessment of diseases involving the HT.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schneeberger M, Gomis R, Claret M. Hypothalamic and brainstem neuronal circuits controlling homeostatic energy balance. J Endocrinol. 2014;220:T25–46.

van Swieten MM, Pandit R, Adan RA, van der Plasse G. The neuroanatomical function of leptin in the hypothalamus. J Chem Neuroanat. 2014;61-62:207–20.

Horvath T, Diano S, Sotonyi P, Heiman M, Tschöp M. Minireview: ghrelin and the regulation of energy balance—a hypothalamic perspective. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4163–9.

Bülow B, Attewell R, Hagmar L, Malmström P, Nordström CH, Erfurth EM. Postoperative prognosis in craniopharyngioma with respect to cardiovascular mortality, survival, and tumor recurrence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3897–904.

Holmer H, Ekman B, Björk J, Nordstöm CH, Popovic V, Siversson A, et al. Hypothalamic involvement predicts cardiovascular risk in adults with childhood onset craniopharyngioma on long-term GH therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;61:671–9.

Holmer H, Pozarek G, Wirfält E, Popovic V, Ekman B, Björk J, et al. Reduced energy expenditure and impaired feeding-related signals but not high energy intake reinforces hypothalamic obesity in adults with childhood onset craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5395–402.

Müller HL, Gebhardt U, Teske C, Faldum A, Zwiener I, Warmuth-Metz M, et al. Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: Results of the multinational prospective trial kraniopharyngeom 2000 after 3-year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:17–24.

Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, Bruner JM. The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:547–51.

Erfurth EM, Holmer H, Fjalldal SB. Mortality and morbidity in adult craniopahryngioma. Pituitary. 2013;16:46–55.

Müller HL. Childhood craniopharyngioma. Pituitary. 2013;16:56–67.

Müller HL, Emser A, Faldum A, Bruhnken G, Etavard-Goris N, Gebhardt U, et al. Longitudinal study on growth and body mass index before and after diagnosis of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3298–305.

Grant DB, Kendall BE, Neville BG, Stanhope R, Watkins KE, Hayward RD. Management of childhood craniopharyngioma: can the morbidity of radical surgery be predicted. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:73–81.

Roth CL. Hypothalamic obesity in craniopharyngioma patients: disturbed energy homeostasis related to extent of hypothalamic damage and its implication for obesity intervention. J Clin Med. 2015;4:1774–97.

Babinski J. Tumeur du corps pituitaire sans acromégalie et avecarrêt de développement des organes génitaux. Rev Neurol. 1900;8:531–3.

Frohlich A. Ein fall von tumor der hypophysis cerebri ohne akromegalie. Wien Klin Rdsch. 1901;15:883–6.

Hochberg I, Hochberg Z. Expanding the definition of hypothalamic obesity. Obes Rev. 2010;11:709–21.

Roth CL, Hunneman DH, Gebhardt U, Stoffel-Wagner B, Reinehr T, Müller HL. Reduced sympathetic metabolites in urine of obese patients with craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:496–501.

Lustig RH. Hypothalamic obesity: the sixth cranial endocrinopathy. Endocrinologist. 2002;12:210–7.

Bray GA, Gallagher TF Jr. Manifestations of hypothalamic obesity in man: a comprehensive investigation of eight patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54:301–30.

Bray GA, Inoue S, Nishizawa Y. Hypothalamic obesity. The autonomic hypothesis and the lateral hypothalamus. Diabetologia. 1981;20:366–77.

Roth C, Wilken B, Hanefels F, Schröter W, Leonhardt U. Hyperphagia in children with craniopharyngioma is associatedwith hyperleptinaemia and a failure in the downregulation of appetite. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:89–91.

Tschöp M, Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Devanarayan V, Ravussin E, Heiman ML. Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes. 2001;50:707–9.

Roth CL, Gebhardt U, Müller HL. Appetite-regulating hormone changes in patients with craniopharyngioma. Obesity. 2011;19:36–42.

Bray GA. Syndromes of hypothalamic obesity in man. Pediatr Ann. 1984;13:525–36.

De Vile CJ, Grant DB, Kendall BE, Neville BG, Stanhope R, Watkins KE, et al. Management of childhood craniopharyngioma: can the morbidity of radical surgery be predicted? J Neurosurg. 1996;85:73–81.

Puget S, Garnett M, Wray A, Grill J, Habrand JL, Bodaert N, et al. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: classification and treatment according to the degree of hypothalamic involvement. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:3–12.

Elliott RE, Sands SA, Strom RG, Wisoff JH. Craniopharyngioma Clinical Status Scale: a standardized metric of preoperative function and posttreatment outcome. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E2.

Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R, Pinto G, Samara-Boustani D, Thalassinos C, et al. Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2376–82.

Van Gompel JJ, Nippoldt TB, Higgins DM, Meyer FB. Magnetic resonance imaging-graded hypothalamic compression in surgically treated adult craniopharyngiomas determining postoperative obesity. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E3.

Mortini P, Gagliardi F, Bailo M, Spina A, Parlangeli A, Falini A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging as predictor of functional outcome in craniopharyngiomas. Endocrine. 2016;51:148–62.

Mallucci C, Pizer B, Blair J, Didi M, Doss A, Upadrasta S, et al. Management of craniopharyngioma: the Liverpool experience following the introduction of the CCLG guidelines. Introducing a new risk assessment grading system. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1181–92.

Ha J, Cohen J, Aziz T, Convit A. Association of obesity-mediated insulin resistance and hypothalamic volumes: possible sex differences. Hind Public Corp. 2013;35:249–59.

Follin C, Gabery S, Petersén Å, Sundgren PC, Björkman-Burtcher I, Lätt J, et al. Associations between metabolic risk factors and the hypothalamic volume in childhood leukemia survivors treated with cranial radiotherapy. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147575.

Fjalldal S, Holmer H, Rylander L, Elfving M, Ekman B, Osterberg K, et al. Hypothalamic involvement predicts cognitive performance and psychosocial health in long-term survivors of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3253–62.

Follin C, Link K, Wiebe T, Moëll C, Björk J, Erfurth EM. Bone loss after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: an observational study with and without GH therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:695–703.

Link K, Moell C, Garwicz S, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Björk J, Thilén U, et al. Growth hormone deficiency predicts cardiovascular risk in young adults treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. J Clin Endrinol Metab. 2004;89:5003–12.

Wilhelmsen L, Tibblin G, Aurell M, Bjure J, Ekström-Jodal B, Grimby G. Physical activity, physical fitness and risk of myocardial infarction. Adv Cardiol. 1976;18:217–30.

Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–25.

Gabery S, Murphy K, Schultz K, Loy CT, McCusker E, Kirik D, et al. Changes in key hypothalamic neuropeptide populations in Huntington disease revealed by neuropathological analyses. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:777–88.

Gabery S, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Lundh SH, Cheong RY, Churchyard A, Chua P, et al. Volumetric analysis of the hypothalamus in Huntington disease using 3T MRI: the image-HD study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117593.

Mai J, Paxinos G, Voss T. Atlas of human brain. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2008.

Harz KJ, Müller HL, Waldeck E, Pudel V, Roth C. Obesity in patients with craniopharyngioma: assessment of food intake and movement counts indicating physical activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5227–31.

Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:292–5.

Goldstone AP, Patterson M, Kalingag N, Ghatei MA, Brynes AE, Bloom SR, et al. Fasting and postprandialhyperghrelinemia in Prader–Willi syndrome is partially explainedby hypoinsulinemia, and is not due to peptide YY3–36 deficiencyor seen in HT obesity due to craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2681–90.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Children's Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Medical Faculty, Lund University, Sweden

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Eva Marie Erfurth received lecture fees from Pfizer and Eli Lilly, B.E. received lecture fees from Novartis and has received fees for consultancy from Pfizer and Shire, all other authors have nothing to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fjalldal, S., Follin, C., Gabery, S. et al. Detailed assessment of hypothalamic damage in craniopharyngioma patients with obesity. Int J Obes 43, 533–544 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0185-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0185-z

This article is cited by

-

Posterior hypothalamic involvement on pre-operative MRI predicts hypothalamic obesity in craniopharyngiomas

Pituitary (2023)

-

Benign Paranasal Sinus Tumors

Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports (2023)

-

Hypothalamic syndrome

Nature Reviews Disease Primers (2022)

-

Body mass index at diagnosis of a childhood brain tumor; a reflection of hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction or lifestyle?

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Cognitive interference processing in adults with childhood craniopharyngioma using functional magnetic resonance imaging

Endocrine (2021)