Abstract

Background/objectives

The frequency of metabolic syndrome (MetS) is significantly higher in schizophrenia (SCH) patients, when compared to the general populatiotin. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether genetic variants T-786C (rs2070744), G894T (rs1799983) and C774T (rs1549758) in the endothelial nitric oxide (NOS3) gene and/or their haplotypes could be associated with the risk of MetS in SCH patients or healthy subjects from Russian population.

Subjects/methods

We performed two case−control comparisons. NOS3 polymorphisms were genotyped in 70 SCH patients with MetS, 190 normal weight SCH patients, 155 MetS patients, and 100 healthy controls. MetS was defined as per the criteria proposed by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Anthropometric, clinical, biochemical parameters, and serum nitrite concentrations were measured in all samples. Haplotype frequency estimations and linkage disequilibrium measures were made using Haploview 4.2.

Results

The higher C allele (P = 0.009) and lower TT genotype (P = 0.008) frequencies of T-786C polymorphism were found in SCH patients with MetS compared to those in normal weight SCH patients. SCH patients with MetS who were carriers of the T-786C TT genotype had lower serum total cholesterol levels in comparison to the CC genotype (P = 0.016). Furthermore, the 774T/894T haplotype was more frequent in non-SCH individuals with MetS compared to healthy controls (P = 0.0004, odds ratio = 2.18, 95% confidence interval 1.4–3.37). Conversely, the most common haplotype 774C/894G was less frequent in MetS patients than in healthy controls (P = 0.013, odds ratio = 0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.41–0.9).

Conclusions

These results indicate that the NOS3 T-786C promoter polymorphism was closely associated with MetS risk in SCH patients. In addition, the haplotypes composed of G894T and C774T polymorphisms are associated with the MetS susceptibility in Russian population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is described as a collection of interrelated factors that lead to an increase in risk for cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). MetS has developed into a global health problem because of its rapidly increasing worldwide prevalence that ranges between 10 and 84% in various populations [1]. There are multiple definitions of MetS, and more recent criteria established by the IDF for practical worldwide use include abdominal obesity, as well as two of the following four factors: elevated fasting plasma glucose concentration or previously diagnosed T2DM, elevated triglyceride levels, high blood pressure and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [2]. Compared with the general population, individuals with SCH have significantly higher frequency rates of MetS, which remains the principal cause of cardiovascular mortality among this population [3, 4]. Several specific factors that may influence susceptibility to MetS in patients with SCH include antipsychotic medication and other severe impacts involving the mental illness itself [5,6,7]. Recent reviews showed that MetS in the general population, and MetS in SCH patients may have both shared and specific underlying genetic determinants [8, 9]. The identification of susceptibility genes and their functional variants corresponding with MetS risk might lead to effective interventions for its prevention and targeted treatment in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations.

The nitric oxide (NO) generated by the enzyme endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) regulates essential cardiovascular and metabolic functions [10]. The production of NO is impaired in patients with MetS features. This impairment can be related to reduced eNOS enzymatic activity and expression, alterations in eNOS phosphorylation, and eNOS uncoupling [11]. Mice that lacked the NOS3 gene that codes for eNOS had certain cardiovascular risk factors which appear to imitate human MetS including hypertension, metabolic insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia [12, 13]. In addition, partial as well as total deletion of the NOS3 gene result in a significant deficiency in coronary vasodilation ability, providing yet more evidence that this gene may be accountable for the relationship between MetS and cardiovascular morbidity [14].

The NOS3 gene is positioned within chromosomal region 7q36, which has shown a suggestive linkage to MetS-related traits in numerous genome-wide scans [15, 16]. Genetic variations in the nucleotide sequence at the promoter, the exons, and the intronic regions of the NOS3 gene have been revealed. Amid the frequently identified NOS3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), G894T (rs1799983) within exon 7 and T-786C (rs2070744) in the 5′-flanking region, are of particular interest because these SNPs may lead to modifications in gene expression, and may even influence interindividual differences related to the activity of the encoded protein [17, 18]. Variations such as these have been implicated in a number of studies investigating MetS, T2DM, and insulin resistance, but studies show inconsistent results [19,20,21,22]. These inconsistencies could perhaps be due to differences in sample size, age, MetS criteria, study design, and interethnic differences within the distribution of NOS3 genetic variants. A recent study showed that synonymous NOS3 SNP C774T in exon 6 (rs1549758) is associated with the development of microvascular and macrovascular complications of T2DM [23, 24]. However, the contribution of C774T nucleotide substitution in cardiometabolic factors still remains controversial [25]. The molecular mechanisms for how these three NOS3 SNPs might affect clinical outcomes are not fully investigated.

To date, no studies have inspected the association between NOS3 haplotypes and MetS in the Russian population. Furthermore, as far as we know, no study as of yet has examined the contribution of NOS3 SNPs to MetS risk in SCH patients. However, one study has been conducted recently which assesses the relationship between NOS3 G894T and T-786C SNPs and endothelial function in a group of SCH subjects who take antipsychotics [26]. The connection of NOS3 T-786C SNP with worse endothelial function was found only in SCH patients who did not have MetS. Hence, the intention of our study was to investigate potential associations of the NOS3 T-786C, G894T and C774T SNPs or their haplotypes with MetS risk in the Russian population and SCH patients. Additionally, associations of these SNPs with serum nitrite concentrations in SCH and non-SCH subjects with MetS were examined.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The first case−control comparison included 70 SCH patients with MetS defined according to the IDF definition (19 males, 51 females) and 190 normal weight SCH patients (122 males, 68 females). Normal weight was established as a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5−25 kg/m2. All SCH patients were recruited from three psychiatric hospitals in Kemerovo, Chita, and Tomsk areas in Siberia (Russia). Ethics approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Local Bioethics Committee of the Mental Health Research Institute (Tomsk, Russia). The main criteria for including the patients in both groups were a clinically verified diagnosis of SCH (ICD-10: F20), Russian ethnicity, Caucasian race identification, and the absence of organic or neurological disorders. Similar proportions of patients in both groups received treatment with atypical antipsychotic drugs (71% of SCH patients with MetS versus 74% normal weight SCH patients). Among the SCH patients with MetS, 16% received first-generation antipsychotics and 13% received combined treatment, whereas these percentages within the sample of normal weight SCH patients were 20 and 6%, respectively. The most frequently prescribed second-generation antipsychotics were risperidone, amisulpride, paliperidone, clozapine, olanzapine, and sertindole. The most common conventional antipsychotic was haloperidol.

For the second case−control comparison, we enrolled 155 Russian MetS patients (60 males, 95 females) from the Regional Clinical Hospital of the Kaliningrad Region and 100 healthy controls (48 males, 52 females) recruited from the same geographic region. Occurrence of MetS was established in accordance with the IDF criteria. All controls from the general population had normal weight and were free of infectious, chronic, and endocrine diseases. The Local Ethics Committee of Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University (Kaliningrad, Russia) approved this study.

Both studies were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was acquired from each subject. To promote homogeneity in samples, all included SCH and non-SCH subjects belonged to Russian Caucasian population. Ethnicity was determined according to both the self-identification of each subject and the subject’s understanding of the ethnicity of their parents and four grandparents. For all cohorts, each participant was interviewed using a questionnaire to determine their cigarette smoking status (non-smoker or current smoker).

Anthropometrical and biochemical assessments

Anthropometric measurements included waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and BMI. The waist circumference was established as the smallest width between coastal margins and iliac crests, when taken at a minimum respiration. Hip circumference was obtained at the maximum extension of the buttocks while the participant was in standing position. Waist-to-hip ratio was found by dividing the waist by the hip values. BMI is the weight of the subject (kg) divided by height of the subject (m2).

For all participants, an overnight fasting venous blood sample was acquired during the same day as flow measurements. Biochemical studies of fasting blood glucose and serum lipid parameters (triglycerides, total cholesterol low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol) were carried out on a biochemical autoanalyzer CA-180 (Furuno Electric Co., Ltd., Hyogo, Japan) using DiaSys reagent kits (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany). The levels of nitrite were determined spectrophotometrically, based on the Griess reaction as described by Moshage et al. [27]. Briefly, 100 μl of serum samples were diluted fourfold with deionized water and deproteinized by adding 20 μl of zinc sulfate (1.85 M). After centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min), supernatants were transferred to wells of microtiter plates in duplicate, followed by the addition of 100 μl of Griess reagent. The absorbance was read at 540 nm after 10 min. The nitrite concentration in each sample was quantified by extrapolation from the sodium nitrite standard curve.

Genotyping

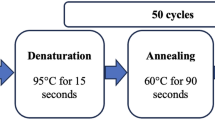

All subjects were genotyped for the T-786C, G894T, and C774T SNPs in the NOS3 gene using allele-specific real-time PCR. The cycling conditions for T-786C and C774T SNPs were 95 °C for 3 min, 50 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 40 s at 65 °C. The PCR protocol for G894T SNP included heating of the reaction mixture for 3 min at 95 °C and 50 amplification cycles performed as follows: 95 °C for 15 s, 63 °C for 40 s. Two PCR amplification reactions were set up for each sample. All PCRs were run on the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria). All three SNPs were genotyped with the SNP genotyping assays (Syntol JSC, Moscow, Russia). Primers and probes were designed and manufactured by Syntol JSC (Moscow, Russia).

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analysis was executed using the Statistica version 10.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). The Levene’s test was utilized to confirm the assumption of equal variances. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to discern whether data followed normal distribution, and the significance of intergroup differences in continuous variables was determined using the independent t test. The gender variables were evaluated using Chi-square testing.

Departures of genotype frequencies from the Hardy−Weinberg proportions were evaluated using Chi-square testing. The allele, genotype, and haplotype frequencies of SNPs were compared between groups by using either Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test when deemed appropriate. One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test was performed to differentiate serum biochemical profiles depending on genotypes among SCH and non-SCH MetS patients.

Haplotype frequency estimations and LD measures were made with the program Haploview version 4.2 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). The solid spine of the LD method was used to estimate the haplotype block as a pairwise D′ value of greater than 0.7 between SNPs. Computation of the odds ratios and its 95% confidence intervals (CI) were performed using the statistical calculator on VassarStats website (http://vassarstats.net/). A P value <0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Results

The comparisons of clinical and biochemical variables among case samples and control samples are represented in Table 1. SCH patients with MetS had a higher BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, blood pressure when compared to normal weight SCH subjects. Compared to healthy controls, MetS patients had higher scores on all four anthropometric parameters, blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and lower HDL-cholesterol levels. Serum nitrite content in SCH patients with MetS were threefold higher than those of normal weight SCH patients, while serum nitrite content in MetS patients was comparable to healthy controls. There was no difference in the smoking frequency among SCH patients with MetS compared with normal weight SCH subjects. Additionally, no significant variance appeared in the proportions of current smokers between MetS patients and healthy controls. When antidiabetic, antihypertensive, and cholesterol-lowering medication was compared between SCH patients with MetS and MetS patients, significant differences were found only for the proportion of patients taking oral antidiabetic agents (Table 2).

Table 3 displays allele and genotype frequencies of NOS3 variants in all cases and controls. In all samples, genotype frequencies did not diverge from the Hardy−Weinberg proportions (all P > 0.05). We found that the T allele (P = 0.009) and the TT genotype (P = 0.008) of T-786C SNP were significantly less common among SCH patients with MetS than in normal weight SCH subjects. The C774T and G894T SNPs were not associated with MetS in SCH patients. However, the prevalence of T allele of the G894T (P = 0.002) and T allele of C774T (P = 0.003) was higher in MetS patients in comparison to healthy controls. The GT (P = 0.011) and TT genotypes (P = 0.0004) of G894T, as well as the heterozygous genotype of C774T (P = 0.035) were more common in MetS patients in comparison to healthy controls. Furthermore, frequencies of the GG genotype (P = 0.002) and CC genotype (P = 0.002), in turn, were less in MetS patients in comparison to healthy controls.

To explore how polymorphisms in the NOS3 gene may be of pathophysiological importance when considering the MetS risk in SCH and non-SCH subjects, we evaluated NOS3 polymorphisms for the associations with MetS biochemical traits in these groups (Table 4). SCH patients with MetS with the TT genotype of the T-786C SNP showed lower levels of total cholesterol compared to carriers of CC genotype (P = 0.016). No significant effect of genotype in relation to serum nitrite level in these groups was discovered.

The LD plot with LD scores (D′ and r2) generated by pairwise comparison of investigated SNPs is shown in Fig. 1. The C774T and G894T SNPs were in strong LD in all samples (D′ > 0.7, r2 > 0.5). Table 5 reflects the frequencies of haplotypes formed by these two NOS3 SNPs. Haplotype analysis showed that the frequency of the 774T/894T haplotype containing both mutant alleles was higher in MetS patients in comparison to healthy controls, and this haplotype was associated with increased occurrence of MetS (P = 0.0004, odds ratio = 2.18, 95% CI 1.4–3.37). In turn, the most common 774C/894G haplotype was associated with a decrease in MetS risk (P = 0.013, odds ratio = 0.61, 95% CI 0.41–0.9). The distribution of haplotype frequencies between SCH patients with MetS and normal weight SCH patients was not of significant difference.

LD plot showing the positions of the three NOS3 gene polymorphisms in SCH patients with MetS (a), normal weight SCH patients (b), MetS patients (c), and healthy controls (d). Values in squares are the pairwise calculation of the LD coefficient D′ and the correlation coefficient r2 expressed in percentage. The color code in D′ plots follows the standard color D′/logarithm (base 10) of odds (LOD) scheme for Haploview: white, |D′| < 1, LOD < 2; shades of pink/red, |D′| < 1, LOD greater than or equal to 2. For r2 plots, different colors designate the extent of LD: for r2 LD plots white (r2 = 0), shades of gray (0 < r2 < 1), black (r2 = 1)

Discussion

In this study three NOS3 gene polymorphisms were investigated in samples of SCH patients with MetS and normal weight, and of these, only the T-786C SNP was established to be significantly associated with MetS in SCH patients. Our finding contradicts the results of Burghardt et al. [26] that showed that the −786C allele can preserve endothelial functioning only for SCH patients who are not subjected to chronic pro-inflammatory state related to MetS. Similarly, they found no association between endothelial functioning and the G894T polymorphism for SCH patients with or without MetS [26]. The association of the C-786 allele with decreased MetS risk has been shown previously in the Taiwanese general population [20]. Two Japanese investigations have also reported about the association of this allele with a decrease in risk for atherosclerosis and reduced serum triglyceride levels during leisurely physical activities [28, 29]. By contrast, the other Japanese study has revealed that the C allele carriers had both higher blood pressure and lower endothelium-dependent vasodilation when compared to non-carriers; this is consistent with our results [30]. Our results of case−control study in SCH patients are consistent with findings from population-based association studies in different general populations. Associations of TC + CC genotypes of the T-786C SNP with MetS in Koreans and with insulin resistance in Japanese subjects without diabetes have been demonstrated [31, 32]. High-risk haplotypes for MetS susceptibility containing the −786C allele have been established in Arab and Spanish populations [19, 21]. We have explored the associations of NOS3 SNPs with MetS risk in the context of SCH, but similar findings related to the T-786C mutant allele and MetS risk were found in studies in patients with different non-psychiatric disorders, in particular ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension and T2DM [32,33,34].

According to Nakayama et al. [17] the rare C allele of the T-786C SNP was connected with a reduction in promoter activity of the NOS3 gene. The molecular mechanism underlying a decrease in promoter activity in individuals carrying the –786C allele might be related to its binding with the replication protein A1. This protein can act as a gene repressor [35]. Two other experiments demonstrated that NOS3 gene and protein expression levels in human endothelial cells under shear stress conditions were greatly decreased or absent for cells possessing a CC genotype [36, 37]. The association of the TT genotype with lower MetS risk in SCH patients revealed in our study is consistent with other research showing the association of this genotype with the maintenance of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in Caucasian hypertensive patients [38]. In the present study, total cholesterol concentration was lower in SCH patients with MetS who happened to be carriers of TT genotype, in comparison with −786CC homozygotes. The revealed association of the T-786C SNP with total cholesterol levels in SCH homozygous carriers of the harmful recessive alleles may be functionally connected to the development of hypercholesterolemia that accompanies MetS. The association of CC genotype with higher serum total cholesterol has been previously described in Caucasian patients with MetS defined according to IDF criteria [39]. Moreover, modulation of the connection between blood pressure and serum cholesterol within the general population has been reported for G894T variant in NOS3 gene [40].

The other main outcome from this study is that the haplotype 774C/894T is associated with an increased MetS risk for the Russian population. The C774T polymorphism, located at exon 6, is functionally neutral, because the C to T transition does not result in amino acid substitution. The effect of this haplotype block of high LD formed by C774T and G894T SNPs on MetS susceptibility can likely be attributed to the G894T substitution resulting in a glutamate or aspartate positioned at 298 of eNOS, respectively. The NOS3 G894T polymorphism was correlated with a reduction in basal NO production for healthy subjects [41]. Tesauro et al. [18] have determined that NOS3 gene product with aspartate, as opposed to glutamate positioned at 298 is likely to cleave in normal tissue and in cells which overexpress eNOS. Other suggested mechanisms for this nonsynonymous mutation are based on the disruption of NOS3 caveolar localization or altered interaction with regulatory proteins including caveolin-1 [42]. Previously, it has been shown that this synonymous SNP in strong LD with the G894T polymorphism was associated with coronary artery disease which is a major adverse consequence of MetS [23, 24]. Considering the disputed data of the effect of the polymorphism in exon 7 on impaired enzyme function, Novoradovsky et al. [43] suggested a hypothesis that both C774T and G894T polymorphisms could be markers of an unknown functional NOS3 SNP, which is in LD with them.

Most studies that report an association of NOS3 gene variants with MetS aspects have utilized NOS3 SNPs alone to describe genetic architecture. For instance, G894T SNP has been individually associated with the features of MetS in Brazilian, Italian, Tunisian, Taiwanese, and Indian populations [22, 44,45,46,47,48]. Furthermore, haplotype -786C/894G was found to be associated with MetS susceptibility in hypertensive subjects in the Spanish population [34]. Similarly, the G894T SNP in LD with other SNPs was found to be linked to MetS susceptibility in Arab and Taiwanese populations [20, 21]. We revealed no associations for G894T or C774T SNPs with biochemical parameters of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in MetS patients with or without SCH. However, some other studies demonstrated the associations between G894T SNP and plasma triglycerides in Caucasian patients with obesity and T2DM [49, 50]. Moreover, NOS3 G894T polymorphism is likely a predictor for persistent hyperglycemia for individuals who have a compromised glucose tolerance and atherogenic lipid profile in Asian populations [30, 46, 51].

This study is the first that assesses and compares serum nitrite levels in SCH patients with MetS and normal BMI. Nitrites are thought to be a main area of storage for circulating NO pool. Alterations in plasma nitrites sensitively reflect acute changes in eNOS activity in human forearm circulation [52]. In our work, the observed highly enhanced synthesis of the plasmatic nitrites in SCH patients with MetS compared to normal weight SCH patients might play a compensatory and protective role neutralizing the endothelium-damaging molecular substances. In contrast to the comparison of circulating nitrite levels in SCH samples, no significant changes in serum nitrites were observed between MetS patients and healthy controls. Our findings are consistent with two previous works that concluded that MetS and T2DM appear not to influence nitrite plasma levels [53, 54]. In another study, whole-blood nitrite concentrations in hypertensive obese children and adolescents did not differ from the controls [55].

We found no influence of all three NOS3 SNPs on nitrite concentrations on MetS in SCH or non-SCH subjects. The lack of evidence for the contribution of T-786C and G894T SNPs to circulating nitrite/nitrate levels has been also reported in other studies conducted in healthy subjects [56, 57]. Interestingly, while NOS3 genotypes did not have a significant association with plasma nitrite concentrations in the study of Metzger et al., the NOS3 haplotype including −786C allele and G894 allele did have an association with lower plasma nitrites when compared to those found in other haplotype groups in healthy subjects [58]. However, the same haplotype did not reveal association with nitrite concentrations in hypertensive or normotensive obese children and adolescents [59]. A lack of effects for all three NOS3 SNPs investigated in our study on nitrite concentrations suggests that these SNPs possibly promote MetS by other mechanisms, thus far undetermined.

Certain limitations of this study should be considered. A major limitation might be the fact that described case−control studies have been conducted in two different Russian regions (Siberia and Kaliningrad Region). However, subjects in all samples were self-reported Caucasian Russian, and all cases were ethnically and geographically matched with control subjects within each case−control comparison. Another limitation of our work includes the somewhat small sample sizes. We also could not exclude the possibility of other factors affecting our results, such as individualized effects of smoking, or the fact that our study contained a higher proportion of women than men in the SCH with MetS group compared to the normal weight SCH group. Finally, the subjects in this study did not have a specific diet prior to blood sampling. Although possible increased dietary nitrate may lead to increased circulating nitrite concentrations, it has been shown that in adults, most plasma nitrites are derived from the oxidation of eNOS-derived NO [60]. Thus, due to the limitations described above, our results should be considered preliminary. To confirm the findings from our study, future studies that have larger samples are necessary. In conclusion, the findings from the study indicate that the NOS3774T/894T haplotype is significantly associated with greater MetS risk than each of the individual harboring alleles considered alone. However, in the presence of SCH and such factors as antipsychotic therapy, G894T and C774T variants probably do not contribute to MetS risk, while the NOS3 T-786C polymorphism seems to be a determining factor. The association of this promoter polymorphism affecting the transcription rate of the NOS3 gene with serum total cholesterol might be a possible mechanism by which the T-786C SNP affects the development of MetS features in SCH subjects.

Data availability

Data are available in the NCBI ClinVar database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) under accession numbers SUB3605688: SCV000680062 and SUB3729182: SCV000692592.

References

Kolovou GD, Anagnostopoulou KK, Salpea KD, Mikhailidis DP. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in various populations. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:362–71.

Alberti KG,Zimmet P,Shaw J,IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059–62.

Darcin AE, Cavus S, Dilbaz N, Kaya H, Dogan E. Metabolic syndrome in drug-naive and drug-free patients with schizophrenia and in their siblings. Schizophr Res. 2015;166:201–6.

Ratliff JC, Palmese LB, Reutenauer EL, Srihari VH, Tek C. Obese schizophrenia spectrum patients have significantly higher 10-year general cardiovascular risk and vascular ages than obese individuals without severe mental illness. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:67–73.

Ryan MC, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode, drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:284–9.

Thakore JH, Mann JN, Vlahos I, Martin A, Reznek R. Increased visceral fat distribution in drug-naive and drug-free patients with schizophrenia. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:137–41.

Margari F, Lozupone M, Pisani R, Pastore A, Todarello O, Zagaria G, et al. Metabolic syndrome: differences between psychiatric and internal medicine patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013;45:203–26.

Malan-Muller S, Kilian S, van den Heuvel LL, Bardien S, Asmal L, Warnich L, et al. A systematic review of genetic variants associated with metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;170:1–17.

Brown AE, Walker M. Genetics of insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:75.

Albrecht EW, Stegeman CA, Heeringa P, Henning RH, van Goor H. Protective role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Pathol. 2002;199:8–17.

Litvinova L, Atochin DN, Fattakhov N, Vasilenko M, Zatolokin P, Kirienkova E. Nitric oxide and mitochondria in metabolic syndrome. Front Physiol. 2015;6:20.

Duplain H, Burcelin R, Sartori C, Cook S, Egli M, Lepori M, et al. Insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2001;104:342–5.

Cook S, Hugli O, Egli M, Vollenweider P, Burcelin R, Nicod P, et al. Clustering of cardiovascular risk factors mimicking the human metabolic syndrome X in eNOS null mice. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:360–3.

Vecoli C, Novelli M, Pippa A, Giacopelli D, Beffy P, Masiello P, et al. Partial deletion of eNOS gene causes hyperinsulinemic state, unbalance of cardiac insulin signaling pathways and coronary dysfunction independently of high fat diet. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104156.

An P, Freedman BI, Hanis CL, Chen Y-DI, Weder AB, Schork NJ, et al. Genome-wide linkage scans for fasting glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Blood Pressure Program: evidence of linkages to chromosome 7q36 and 19q13 from meta-analysis. Diabetes. 2005;54:909–14.

Li W-D, Dong C, Li D, Garrigan C, Price RA. A genome scan for serum triglyceride in obese nuclear families. J Lipid Res. 2004;46:432–8.

Nakayama M, Yasue H, Yoshimura M, Shimasaki Y, Kugiyama K, Ogawa H, et al. T-786→C mutation in the 5’-flanking region of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with coronary spasm. Circulation. 1999;99:2864–70.

Tesauro M, Thompson WC, Rogliani P, Qi L, Chaudhary PP, Moss J. Intracellular processing of endothelial nitric oxide synthase isoforms associated with differences in severity of cardiopulmonary diseases: cleavage of proteins with aspartate vs. glutamate at position 298. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2832–5.

González-Sánchez JL, Martinez-Larrad MT, Saez ME, Zabena C, Martinez-Calatrava MJ, Serrano-Rios M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase haplotypes are associated with features of metabolic syndrome. Clin Chem. 2007;53:91–97.

Liu CS, Huang RJ, Sung FC, Lin CC, Yeh CC. Association between endothelial nitric oxide synthase polymorphisms and risk of metabolic syndrome. Dis Markers. 2013;34:187–97.

Alkharfy KM, Al-Daghri NM, Al-Attas OS, Alokail MS, Mohammed AK, Vinodson B, et al. Variants of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene are associated with components of metabolic syndrome in an Arab population. Endocr J. 2012;59:253–63.

Monti LD, Barlassina C, Citterio L, Galluccio E, Berzuini C, Setola E, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase polymorphisms are associated with type 2 diabetes and the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes. 2003;52:1270–5.

Levinsson A, Olin AC, Björck L, Rosengren A, Nyberg F. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) single nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with coronary heart disease and hypertension in the INTERGENE study. Nitric Oxide. 2014;39:1–7.

Taverna MJ, Elgrably F, Selmi H, Selam JL, Slama G. The T-786C and C774T endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms independently affect the onset pattern of severe diabetic retinopathy. Nitric Oxide. 2005;13:88–92.

Min BW, Na JY, Juhng SW, Park MS, Park JT, Kim HS. A polymorphism (G894T) in eNOS increases the risk of coronary atherosclerosis rather than intracranial atherosclerosis in Koreans. Acta Neurol Belg. 2010;110:255–62.

Burghardt K, Grove T, Ellingrod V. Endothelial nitric oxide synthetase genetic variants, metabolic syndrome and endothelial function in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:349–56.

Moshage H, Kok B, Huizenga JR, Jansen PL. Nitrite and nitrate determinations in plasma: a critical evaluation. Clin Chem. 1995;41:892–6.

Hashimoto M, Miyai N, Hattori S, Iwahara A, Utsumi M, Arita M, et al. Age and gender differences in the influences of eNOS T-786C polymorphism on arteriosclerotic parameters in general population in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2016;21:274–82.

Higashibata T, Hamajima N, Naito M, Kawai S, Yin G, Suzuki S, et al. eNOS genotype modifies the effect of leisure-time physical activity on serum triglyceride levels in a Japanese population. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:150.

Imamura A, Takahashi R, Murakami R, Kataoka H, Cheng XW, Numaguchi Y, et al. The effects of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms on endothelial function and metabolic risk factors in healthy subjects: the significance of plasma adiponectin levels. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:189–95.

Kang MK, Kim OJ, Jeon YJ, Kim HS, Oh SH, Kim JK, et al. Interplay between polymorphisms in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene and metabolic syndrome in determining the risk of ischemic stroke in Koreans. J Neurol Sci. 2014;344:55–59.

Ohtoshi K, Yamasaki Y, Gorogawa S, Hayaishi-Okano R, Node K, Matsuhisa M, et al. Association of -786T-C mutation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene with insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1594–601.

Vecoli C, Andreassi MG, Liga R, Colombo MG, Coceani M, Carpeggiani C, et al. T−786→C polymorphism of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with insulin resistance in patients with ischemic or non ischemic cardiomyopathy. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:92.

Fernandez ML, Ruiz R, Gonzalez MA, Ramirez-Lorca R, Couto C, Ramos A, et al. Association of NOS3 gene with metabolic syndrome in hypertensive patients. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:413–8.

Miyamoto Y, Saito Y, Nakayama M, Shimasaki Y, Yoshimura T, Yoshimura M, et al. Replication protein A1 reduces transcription of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene containing a–786T→C mutation associated with coronary spastic angina. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2629–37.

Cattaruzza M, Guzik TJ, Slodowski W, Pelvan A, Becker J, Halle M, et al. Shear stress insensitivity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression as a genetic risk factor for coronary heart disease. Circ Res. 2004;95:841–7.

Asif AR, Oellerich M, Armstrong VW, Hecker M, Cattaruzza M. T-786C polymorphism of the NOS-3 gene and the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress—a proteome analysis. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3161–8.

Rossi GP, Taddei S, Virdis A, Cavallin M, Ghiadoni L, Favilla S, et al. The T-786C and Glu298Asp polymorphisms of the endothelial nitric oxide gene affect the forearm blood flow responses of Caucasian hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:938–45.

Misiak B, Krolik M, Kukowka A, Lewera A, Leszczynski P, Stankiewicz-Olczyk J, et al. The role of −786T/C polymorphism in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene in males with clinical and biochemical features of the metabolic syndrome. Int J Endocrinol. 2011;2011:458750.

Pereira AC, Sposito AC, Mota GF, Cunha RS, Herkenhoff FL, Mill JG, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene variant modulates the relationship between serum cholesterol levels and blood pressure in the general population: new evidence for a direct effect of lipids in arterial blood pressure. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:193–200.

Veldman BA, Spiering W, Doevendans PA, Vervoort G, Kroon AA, de Leeuw PW, et al. The Glu298Asp polymorphism of the NOS 3 gene as a determinant of the baseline production of nitric oxide. J Hypertens. 2002;20:2023–7.

Joshi MS, Mineo C, Shaul PW, Bauer JA. Biochemical consequences of the NOS3 Glu298Asp variation in human endothelium: altered caveolar localization and impaired response to shear. FASEB J. 2007;21:2655–63.

Novoradovsky A, Brantly ML, Waclawiw MA, Chaudhary PP, Ihara H, Qi L, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase as a potential susceptibility gene in the pathogenesis of emphysema in α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:441–7.

Piccoli JC, Gottlieb MG, Castro L, Bodanese LC, Manenti ER, Bogo MR, et al. Association between 894G T endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms and metabolic syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;52:1367–73.

Nasr HB, Dimassi S, M’Hadhbi R, Debbabi H, Kortas M, Tabka Z, et al. Functional G894T (rs1799983) polymorphism and intron-4 VNTR variant of nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) gene are susceptibility biomarkers of obesity among Tunisians. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;10:465–75.

Hsieh MC, Hsiao JY, Tien KJ, Chang SJ, Lin PC, Hsu SC, et al. The association of endothelial nitric oxide synthase G894T polymorphism with C-reactive protein level and metabolic syndrome in a Chinese study group. Metabolism. 2008;57:1125–9.

Lee YC, Huang SP, Liu CC, Yang YH, Yeh HC, Li WM, et al. The association of eNOS G894T polymorphism with metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9:837–43.

Angeline T, Krithiga H, Isabel W, Asirvatham A, Poornima A. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphism (G894T) and diabetes mellitus (type II) among South Indians. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2011;2011:462607.

Teixeira TG, Tibana RA, Nascimento DD, de Sousa NM, de Souza VC, Vieira DC, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase Glu298Asp gene polymorphism influences body composition and biochemical parameters but not the nitric oxide response to eccentric resistance exercise in elderly obese women. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2015;36:482–9.

Ukkola O, Erkkilä PH, Savolainen MJ, Kesäniemi YA. Lack of association between polymorphisms of catalase, copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD), extracellular SOD and endothelial nitric oxide synthase genes and macroangiopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Intern Med. 2001;249:451–9.

Tso AW, Tan KC, Wat NM, Janus ED, Lam TH, Lam KS. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase G894T (Glu298Asp) polymorphism was predictive of glycemic status in a 5-year prospective study of Chinese subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Metabolism. 2006;55:1155–8.

Lauer T, Preik M, Rassaf T, Strauer BE, Deussen A, Feelisch M, et al. Plasma nitrite rather than nitrate reflects regional endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity but lacks intrinsic vasodilator action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12814–9.

da Fonseca LJS, Nunes-Souza V, da Silva Guedes G, Schettino-Silva G, Mota-Gomes MA, Rabelo LA. Oxidative status imbalance in patients with metabolic syndrome: Role of the myeloperoxidase/hydrogen peroxide axis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:898501.

Ferlito S, Gallina M. Nitrite plasma levels in type 1 and 2 diabetics with and without complications. Minerva Endocrinol. 1999;24:117–21.

de Miranda JA, Lacchini R, Belo VA, Lanna CMM, Sertorio JT, Luizon MR, et al. The effects of endothelial nitric oxide synthase tagSNPs on nitrite levels and risk of hypertension and obesity in children and adolescents. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;29:109–14.

Moon J, Yoon S, Kim E, Shin C, Jo SA, Jo I. Lack of evidence for contribution of Glu298Asp (G894T) polymorphism of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene to plasma nitric oxide levels. Thromb Res. 2002;107:129–34.

Nagassaki S, Metzger IF, Souza-Costa DC, Marroni AS, Uzuelli JA, Tanus-Santos JE. eNOS genotype is without effect on circulating nitrite/nitrate level in healthy male population. Thromb Res. 2005;115:375–9.

Metzger IF, Sertório JT, Tanus-Santos JE. Modulation of nitric oxide formation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene haplotypes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:987–92.

Souza-Costa DC, Belo VA, Silva PS, Sertorio JT, Metzger IF, Lanna CM, et al. eNOS haplotype associated with hypertension in obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2011;35:387–92.

Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, Rassaf T, Schindler A, Picker O, et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:790–6.

Acknowledgements

The research was financially supported by the Russian Scientific Foundation under Grant No. 17-15-01111 for the portion of the study involving MetS patients and healthy subjects, and Fundamental Research for Biomedical Technologies Program of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences No. 1.42 “Development of technology for predicting the side metabolic effects of antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia based on the function of endothelial nitric oxide synthase” for the portion of the study involving SCH subjects. The case−control comparison involving non-SCH subjects was conducted within the framework of National Research Tomsk Polytechnic University Competitiveness Enhancement Program and Competitiveness Increase Program of Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University (“Organization of Scientific Research 20.4986.2017/6.7”), which did not provide financial assistance for research. The authors thank Dr. Mariia Vasilenko, (Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Kaliningrad, Russia) who assisted in collecting and compiling clinical data from MetS patients and healthy controls, and Dr. Tatiana Polushina (University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway) for the statistical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fattakhov, N., Smirnova, L., Atochin, D. et al. Haplotype analysis of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) genetic variants and metabolic syndrome in healthy subjects and schizophrenia patients. Int J Obes 42, 2036–2046 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0124-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0124-z

This article is cited by

-

The incidence of NOS3 gene polymorphisms on newborns with large and small birth weight

Molecular Biology Reports (2020)