Abstract

Background

To determine whether hypothyroidism is associated with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and how this association is influenced by race–ethnicity, sex, and timing of exposure.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using records from 397,201 children who were delivered from 1991 to 2011 and remained health plan members from 1993 to 2014.

Results

Children of hypothyroid women had higher ASD rates than children of women without the diagnosis (2.14 vs. 1.62/1,000 person-years; adjusted hazard ratios (adj.HR), 1.31; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.13–1.53). This occurred in women diagnosed before as well as during pregnancy. Maternal hypothyroidism was associated with ASD for both boys (3.93 vs. 2.62/1,000 person-years; adj.HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07–1.50) and girls (1.10 vs. 0.61/1,000 person-years; adj.HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.10–2.08). Of women with a diagnosis of hypothyroidism during pregnancy, normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (fT4) levels were not associated with an increased risk of ASD in children. Compared with white children, prenatal hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk of ASD in children of Hispanics (adj.HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01–1.17) and women of other/mixed race–ethnicity (adj.HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.00–1.16).

Conclusion

Maternal hypothyroidism is associated with ASD in children in a manner dependent on race–ethnicity. Management of maternal hypothyroidism may ameliorate the risk of ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) affect 1 in 68 children, and their prevalence has been increasing over the past 20 years. Prevalence estimates, however, vary greatly within and across gender and racial/ethnic groups (1). These conditions may have their origins during fetal development, and both genetic and environmental factors are likely to be involved (2, 3). The specific genes and environmental exposures that increase the risk for ASD, however, have not yet been identified.

Maternal thyroid hormones are required for neurodevelopment. Many genes that have polymorphisms or whose dysfunction has been linked to ASD (e.g., bdnf and reelin) are regulated by triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) (4). Administration of propylthiouracil, a drug that induces hypothyroidism, in a pregnancy animal model resulted in changes in locomotor activity and learning in the pups that are consistent with ASD (5). Clinical studies also suggest that thyroid dysfunction may increase the risk of ASD. Although thyroid hormone concentrations in infants at the time of birth were associated with an increased risk of ASD in some studies (6, 7) and in certain subgroups but not others (8), maternal concentrations of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) at mid-pregnancy were inversely correlated with risk of ASD in children (9). Maternal autoantibodies to thyroid peroxidase were associated with an increased risk of ASD (10), and a family history of thyroid autoimmune diseases is more prevalent in autistic children (11). European studies have also suggested that hypothyroidism during pregnancy increases the risk of ASD (12, 13). However, to our knowledge, no studies have assessed the relationship between maternal hypothyroidism and the risk of ASD in children in the United States where there are wide racial/ethnic disparities. Therefore, we used electronic medical records (EMRs) from the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) system to evaluate whether maternal hypothyroidism is associated with increased risk of ASD in children and whether this risk is modified by race–ethnicity, fetal sex, and timing of exposure.

METHODS

This study, approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board, employed a retrospective cohort approach to examine the association between maternal hypothyroidism and ASD in the singleton, live-born children.

Subjects

We used perinatal service, maternal and child inpatient and outpatient medical care, and laboratory and pharmacy records. Information extracted from the patient’s EMRs included maternal medical and obstetrical conditions and procedures, fetal and neonatal outcomes, maternal sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics, parental race/ethnicity, and the child’s age, sex, and medical history. The reliability and validity of these data sources have been previously published (14, 15). Parental demographic and maternal health records were linked to child records using medical record numbers unique for each pregnancy. The study population was drawn from a total of 594,638 births. To be eligible, children must have been born to KPSC members in KPSC hospitals between 1 January 1991 and 31 December 2011, be a singleton birth with a gestational age of 280/7 through 426/7 weeks, and be a KPSC health plan member for ≥3 months between 2 and 17 years of age during the years 1993–2014. Multiple gestation pregnancies were excluded as higher human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations in multiple gestations known to suppress the TSH level. Births at <280/7 weeks were excluded because of their high incidence of morbidity and mortality. A total of 397,201 children were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1).

Exposure and Outcome Measures

Definition of the exposure to hypothyroidism was based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code 244.x, and medication was prescribed to treat the condition. Blood levels of TSH (>90.4 pmol/ml) and free thyroxine (fT4, <10.45 pmol/ml) obtained from women with a clinical diagnosis of hypothyroidism (99.4% of women with the diagnosis) were used to determine how biochemical hypothyroidism may affect the risk of ASD diagnosis. In this study, data on prepregnancy hypothyroidism were obtained from women who had uninterrupted medical and pharmacy coverage for at least a 3-month period before pregnancy. Gestational hypothyroidism is defined as hypothyroidism with onset or first diagnosis during pregnancy in women without a prior history of the condition and used as a surrogate marker of the timing of initial in utero exposure. Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is against routine prenatal thyroid testing but advocates testing only in at-risk women, symptomatic women, or those with personal history of thyroid disease or other related medical conditions (16). Therefore, in this study, women without the clinical diagnosis of hypothyroidism formed the comparison group. The outcome variable was physician-diagnosed ASD in children between 2 and 17 years. In the KPSC system, the clinical diagnosis of ASD was largely based on definitive diagnosis by a child/adolescent psychiatrist, developmental/behavioral pediatrician, child psychologist, or neurologist who adhered to a standard protocol (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) (17). Therefore, these diagnoses are assumed to be accurate because they were made based on gold-standard diagnostic measures. In a preliminary analysis for a related project, 96% of ADHD children were diagnosed by specialists trained to diagnose and treat the condition (18). ASD diagnoses were made in contracting hospitals or unrecognizable health-care centers only in a small minority of children, and the validity of their diagnoses was assessed through medical record review by clinical experts and suggested to use at least two ASD diagnoses (19). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) codes for any of the following conditions: autistic disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, Rett’s disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified were used to ascertain ASD cases. Children with at least one documented DSM-IV code for ASD on any two separate visits during the follow-up period formed the ASD cases.

Potential confounders and effect modifiers extracted from the EMRs included maternal characteristics at the time of pregnancy (age (grouped as <20, 20–29, 30–34, and ≥35 years), education (<12, 12, and ≥13 years of completed schooling), median family household income based on the 2010 US census tract of residence (<$29,999, $30,000–$49,000, $50,000–$69,999, $70,000–$89,999, and ≥$90,000), parity, timing of prenatal care initiation (early or first trimester vs. later/no prenatal care or second trimester), clinically estimated gestational age, and smoking habits (yes or no)), year of diagnosis, and child’s sex (male or female). Information on child race/ethnicity was based on maternal and paternal race/ethnicity recorded in the EMRs and grouped as non-Hispanic white (White) if a child was born to non-Hispanic white mother and father. The same applies to non-Hispanic black (Black), Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander race/ethnicity. The Other/Mixed (other) race/ethnicity category includes children born from inter-racial/interethnic relationship. Data on child’s age were ascertained at the time of first diagnosis. However, information on child’s medical history was obtained from EMRs during the follow-up period. Follow-up began at birth and ended with ASD diagnosis or when censoring occurred, on the earliest of the following dates: health plan disenrollment, 17th birthday, non-ASD-related death, or end of study (31 December 2014).

Data Analyses

The distribution of maternal and child characteristics based on ASD status was compared using χ2-tests. Cumulative incidence rates were estimated by dividing the number of ASD cases by the person-years of follow-up. Because hypothyroidism that may recur between pregnancies and ASD also tends to recur in siblings, such clustered observations are likely to be correlated. Therefore, we used Marginal Cox proportional hazards model that accounts for within-cluster correlation to estimate crude and adjusted hazard ratios (adj.HR) (20) of the association between prenatal exposure to hypothyroidism and ASD risk. This approach used sandwich estimate for the covariance matrix to adjust for correlated observations. The outcome variable was “time-to-event,” with the “event” being a diagnosis of ASD, and “event-time” being the time between child’s delivery and the date of first diagnosis for children with ASD or the last date of visit for children without ASD. This approach would appropriately account for varying follow-up times of cohort members. The HR is estimating the risk of developing ASD in the exposed children as compared with the risk in the unexposed children of the same age. Confounding variables were chosen a priori or if they resulted in a P value<0.05 for differences between each potential confounding factor and ASD status of participating children.

As there is sex and racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of ASD and risks differ by gestational age at birth (21), and that the level of TSH among black women is much lower than that among their white counterparts (22), we repeated the analysis and adj.HRs were derived to assess the relationship between prenatal exposure to hypothyroidism and ASD risk for each sex (boys and girls), race/ethnicity, and preterm and term birth categories. Departure from the proportionality assumption in these models was checked graphically. Furthermore, disparities in the association between prenatal exposure to hypothyroidism and ASD risk across sex (girls as reference) and race/ethnicity (white as a reference) groups were compared. Diagnosing ASD in children with accompanying developmental and emotional disorders (mental retardation, developmental dyslexia, deficits in language processing, conduct disorder, irritability, depressed mood, and bipolar/anxiety disorders), and congenital anomalies is challenging. Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding all children with these conditions to assess its impact on our findings. Finally, because children aged 2–3 years may have a shorter follow-up period to capture enough events and as such may potentially have affected our risk estimates, we performed a sensitivity analysis after limiting the cohort to children aged ≥4 years. In all analyses, children of women without the clinical diagnosis of hypothyroidism served as the reference group. HR with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to quantify the magnitude of associations. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

During the study period, the prevalence of chronic hypothyroidism was 2.2% and the incidence of hypothyroidism first diagnosed during pregnancy was 2.4/1,000 person-years. The mean age at first diagnosis of ASD was ~5.1 years (SD=3.4). The median follow-up times and its interquartile ranges (IQR) for children with and without exposure to hypothyroidism were 3 (IQR=2, 17) and 4 (IQR=2, 17) years, respectively. There were significant differences between women whose children developed ASD (n=6,475) with those who did not (n=390,726), Table 1. Women in the ASD group were older, better educated, at lower parity, and received prenatal care earlier. Their children were born earlier and were more often males of White race.

Children of hypothyroid women had higher rates of ASD than children of women without the diagnosis (2.14 vs. 1.62‰; HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.25–1.68). This trend persisted after adjusting for variables listed in Table 1 (adj.HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13–1.53). Hypothyroidism diagnosed before (2.56 vs. 1.62‰, adj.HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.07–1.58) or during (2.43 vs. 1.62‰, adj.HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.05–1.69) pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of ASD. However, of the women diagnosed with hypothyroidism during pregnancy, only those diagnosed during the first trimester (2.14 vs. 1.62‰, HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.08–1.98) were at an increased risk of delivering a baby who would be diagnosed with ASD. This trend continued after adjustment for potential confounders (adj.HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.01–1.85; Table 2). Because findings on trimester-specific associations were based on a small sample, caution must be taken when interpreting these results. Sensitivity analyses after (i) limiting the cohort to children aged 4–17 years and (ii) excluding children with a history of accompanying developmental or emotional disorders or congenital anomalies did not produce any significant changes in the magnitude and direction of the associations.

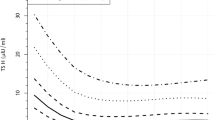

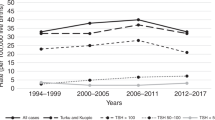

Autism diagnoses occurred at younger ages for children born to mothers with hypothyroidism diagnosis than those born to mothers without the diagnosis (Figure 2a). This trend persisted when data were further stratified by pre- vs. within-pregnancy diagnosis and child sex (Figure 2b). When the analysis was stratified by the levels of TSH and fT4, more children of women with the diagnosis and abnormal levels of hormone (TSH >90.4 pmol/ml (adj. HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.11–2.15] or fT4 <10.45 pmol/ml (adj.HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.26–2.50)) went on to develop ASD when compared to children of women without the diagnosis (Figure 3a). However, children born to women with a pre-pregnancy diagnosis of hypothyroidism tended to be at greater risk of ASD even if the TSH and fT4 levels were normal. Incidence rates for ASD were also 1.4–2-fold higher in women with hypothyroidism diagnosis, regardless of hormone values (Figure 3c). High TSH or low T4 levels resulted in the highest HRs for both boys and girls when they occurred during pregnancy (data not shown).

Effects of TSH (a, c) and fT4 (b, d) levels on risk of autism in children of hypothyroid women. Adjusted hazard ratios with 95% CI (a, b) and incidence rates (c, d) of autism in children when hypothyroidism was diagnosed before or within the index pregnancy are shown. Abnormal TSH levels: A TSH reading above 90.4 pmol/ml is considered high and a fT4 reading below 10.45 pmol/ml is considered low. Hormone-level readings came from women with suspected hypothyroid disease. The control (reference) group consists of women without the diagnosis of hypothyroidism. CI, confidence interval; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

In a predefined category of gestational age, maternal hypothyroidism was not significantly associated with ASD in children born at 28–36 weeks (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.77–1.94). The association between maternal hypothyroidism and ASD in term (37–42 weeks) births, however, was similar to that of the overall analysis (adj.HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.13–1.55; Table 3). Nonetheless, tests for interaction between hypothyroidism and preterm and term birth status with ASD risk did not reach statistical significance (P value=0.69).

ASD occurred approximately four times as often in boys as in girls. In the crude analysis, hypothyroidism was a slightly stronger risk factor for ASD for girls than it was for boys (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.25–2.37 vs. HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.19–1.67), but attenuated with adjustment (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.10–2.08 vs. HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07–1.50; Table 3). However, tests for interaction between hypothyroidism status and child’s sex with ASD risk did not reach statistical significance (P value=0.30). For boys, maternal hypothyroidism increased the risk of ASD to an equivalent degree when diagnosed before, or during, pregnancy. Most of these associations, however, became nonsignificant after adjustment for covariates (Table 3). Girls, however, were at greater risk of ASD when maternal hypothyroidism was diagnosed pre-pregnancy as opposed to during pregnancy. Boys born to mothers diagnosed with hypothyroidism before or during pregnancy were diagnosed with ASD at younger ages than those born to women without the diagnosis (Figure 2b).

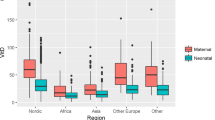

When we repeat the analysis separately for each race/ethnic group (Table 4), the association between maternal hypothyroidism and ASD was significant in Asian/Pacific Islanders (adj.HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.08–2.60) and Other/Multiple race ethnicities (adj.HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.09–1.96) but not in Whites (adj. HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.97–1.67), Hispanics (adj. HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.81–1.47), and Blacks (adj. HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.74–2.79). In a further stratified analysis by the pregestational and gestational hypothyroidism status, a significant association between hypothyroidism and ASD risk was observed in Blacks (adj. HR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.00–5.00) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (adj. HR, 3.16; 95% CI, 1.92–5.19) when diagnosed during, but not prior to, pregnancy. Children of Other/Multiple race ethnicities were only at an increased risk for ASD if their mothers’ hypothyroidism was diagnosed before pregnancy (adj. HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.25–2.51).

In examining disparities across race/ethnicity groups, no significant interaction between race/ethnicity with hypothyroidism on ASD risk was detected (P value=0.72).

Discussion

Although the association between hypothyroidism and ASD has been proposed, most previous studies have used neonatal samples that poorly reflect in utero exposure. Therefore, results are varied depending on which subgroup has been analyzed (7). We found that maternal hypothyroidism may increase the risk of ASD in a manner that is dependent on timing of diagnosis (before vs. within-pregnancy diagnosis) and race–ethnicity. Our findings are consistent with studies from Denmark (12) and the Netherlands (23) but with notable differences. Roman et al. (13) found that severe hypothyroidism (fT4 <10.99 pmol/ml) in the first trimester of pregnancy resulted in a 4-fold increase in the child testing positive on screening instruments for autism (Social Responsiveness Scale and the Pervasive Developmental Problems subscale scores of the Child Behavior Checklist for Toddlers in the 95th and 98th percentile). However, we only found that maternal hypothyroidism in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of ASD by ~30% when adjusted for covariates, a much weaker association. There are several key differences between our studies that may account for these differences. First, Roman et al. may have sampled from a patient population with greater rates of hypothyroidism in pregnancy. Approximately 3.5% of the patients in their sample were diagnosed as being hypothyroid because of severe hypothyroxinemia (13) but only 2.1% of our patients were classified as hypothyroid. Hypothyroidism is frequently underdiagnosed in pregnancy (23) and may have been in our study too. The data reported by Roman et al. were a part of a larger population cohort study (Generation R) in which T4 levels were quantified in batches of archived samples and subjects with hypothyroidism may have been untreated accounting for a greater risk. When we stratified hypothyroid women based on TSH and fT4 levels, we found that children of hypothyroid women with hypothroxinemia (TSH >90.4 pmol/ml or fT4 <10.45 pmol/ml) were at a greater risk of developing ASD similar to their findings. Our findings that women with a prepregnancy hypothyroidism diagnosis but normal TSH and fT4 levels suggest that, even when controlled, maternal hypothyroidism may remain a risk factor for ASD in children. Although there was an elevated risk of autism in children of women diagnosed with hypothyroidism in pregnancy but having normal TSH and fT4 levels, results did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that well-controlled hypothyroidism during pregnancy may reduce the risk of autism in children.

By using confirmed clinical diagnoses from EMRs, we found that 1.6% of our population had ASD. This closely matches the most recent estimates by the CDC of 1/68 (1.5%) (1) and is lower than the 2% rate that Roman et al. identified as being probable autistics based on the Social Responsiveness Scale and Pervasive Developmental Problems scores (13). The findings reported in a population-based study of medical records in Denmark were closer to ours in terms of ASD rates, maternal hypothyroidism, and the adj.HRs for maternal hypothyroidism to increase the risk of ASD diagnosis (12). Neither of the previous studies examined how risk of ASD may vary with the timing of diagnosis of hypothyroidism and how results could vary with sex or race–ethnicity.

ASD was diagnosed about four times as often in boys than in girls in our cohort and is consistent with the general US trend. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the sex difference in the autism rate that include under-/misdiagnosis, better adaptation, or hormonal factors in girls that reduce their susceptibility to the condition (24, 25). Both boys and girls were at an increased risk when hypothyroidism was diagnosed pre-pregnancy but the HR was slightly higher for girls than it was for boys (girls did have a lower incidence overall, however). The incidence rate for boys was relatively consistent, regardless of when maternal hypothyroidism was diagnosed, at 3.7–4.1 cases/1,000 person-years. However, for girls, the highest incidence rate for ASD occurred when maternal hypothyroidism was diagnosed before pregnancy (1.1 events/1,000 person-years). Sex differences in neurodevelopment are well documented and anatomical differences have been noted in regions such as the amygdala, cerebellum, corpus callosum, and hippocampus that have been implicated in the development of ASD (26, 27). Recent studies with diffusion tensor imaging also demonstrated sex differences in terms of connectivity between different regions of the brain (28). The molecular mechanisms behind these differences in neuronal anatomy and interconnectivity are poorly understood but could be reflective of genes regulated by thyroid hormones.

Hypothyroidism may be the result of a number of conditions such as inflammatory disease, autoimmune disorders, or iodine deficiencies. The bulk of our hypothyroid patients are so because of autoimmune thyroiditis or iatrogenic ablation. Thyroid hormones may also be altered by air pollution, pesticides, and persistent organic pollutants (29). Exposure to perchlorate salts may also introduce hypothyroidism by inhibiting uptake of iodine to disrupt neurodevelopment (30). Maternal residence near road ways (31), regions with high fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution (32), and agricultural pesticides (33) have been suggested to increase the risk of ASD in children. Other studies have suggested that in utero exposure to environmental compounds such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) (34) may increase the risk of ASD-like symptoms in children. PBDEs have significant structural similarity to T3 and T4 and can interfere with thyroid receptor-regulated gene expression and inhibit T4-stimulated arborization and growth of the Purkinje cells (35). Reduced Purkinje cell size is a neuroanatomical feature of autism (36). PBDEs may be especially relevant to our patient population because Californian women likely have the highest PBDE exposures in the world (37). PBDEs increase the risk of preterm birth (38) and intrauterine growth restriction (39), and pregnancy outcomes whose risk is increased by maternal hypothyroidism.

Although formal testing for interactions between hypothyroidism and sex (male and female (P=0.30)), gestational age (preterm and term birth (P=0.69)), and race/ethnicity categories (P=0.72) did not reach statistical significance, our predefined stratified analyses showed that the risk associated with hypothyroidism may differ across these categories, suggesting the need for further investigation. It is known that testing for interactions requires a lot more sample size than testing for the main effects.

Strengths of our study include the use of a large sample from a multiethnic population with high rates of follow-up over a 17-year period and detailed patient records. According to the KPSC guidelines (revised in April 2013) (40), the diagnosis and treatment of ASD in young children are suggested to be made by health-care professionals with expertise to diagnose and treat the condition. The health-care professionals perform behavioral and developmental surveillance at all well-child check-up visits (as early as 4 months) followed by specific screening instruments when there is suspicion of developmental delay (beginning at 18 months). Routine screening for thyroid disorders and the stringent criteria used by KPSC in diagnosis and treatment of ASD minimize risks of patient misclassification. Because of the prospective nature of data collection, our findings are resistant to sampling and recall biases.

Our study is not without limitations, however. We were unable to distinguish subclinical from overt hypothyroidism in our cohort and its impact on ASD risk since patients was not screened for it which is in line with current American Congress of Obstetrician and Gynecologist recommendations (41). Lack of data from screening instruments such as the Social Responsiveness Scale score makes it difficult to comment on the severity of or types of autistic traits in diagnosed children. However, younger ages of ASD diagnosis in children of hypothyroid mothers suggest that hypothyroidism may enhance the severity as well as the rate of ASD. One potential source of bias is diagnostic suspicion (exposure suspicion) bias that occurs when exposed and unexposed patients differ in measurement (both the intensity and diagnostic process) of health outcome statuses. Another potential limitation of the study is that we did not control for perinatal exposure to environmental toxins as this information was not available in the medical records.

In summary, we found that maternal hypothyroidism is associated with an increased risk of ASD in children in a manner dependent upon race–ethnicity. Management of maternal hypothyroidism may ameliorate the risk of this increasingly common neurodevelopmental disorder.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ2014;63:1-21.

Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I et al. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med 1995;25:63–77.

Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:1095–102.

Berbel P, Navarro D, Roman GC . An evo-devo approach to thyroid hormones in cerebral and cerebellar cortical development: etiological implications for autism. Front Endocrinol 2014;5:146.

Sadamatsu M, Kanai H, Xu X, Liu Y, Kato N . Review of animal models for autism: implication of thyroid hormone. Congenit Anom 2006;46:1–9.

Hoshiko S, Grether JK, Windham GC, Smith D, Fessel K . Are thyroid hormone concentrations at birth associated with subsequent autism diagnosis? Autism Res 2011;4:456–63.

Lyall K, Anderson M, Kharrazi M, Windham GC . Neonatal thyroid hormone levels in association with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 2017;10:585–92.

Soldin OP, Lai S, Lamm SH, Mosee S . Lack of a relation between human neonatal thyroxine and pediatric neurobehavioral disorders. Thyroid 2003;13:193–8.

Yau VM, Lutsky M, Yoshida CK et al. Prenatal and neonatal thyroid stimulating hormone levels and autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45:719–30.

Brown AS, Surcel HM, Hinkka-Yli-Salomaki S, Cheslack-Postava K, Bao Y, Sourander A . Maternal thyroid autoantibody and elevated risk of autism in a national birth cohort. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2015;57:86–92.

Wu S, Ding Y, Wu F et al. Family history of autoimmune diseases is associated with an increased risk of autism in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;55:322–332.

Andersen SL, Laurberg P, Wu CS, Olsen J . Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder in children born to mothers with thyroid dysfunction: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BJOG 2014;121:1365–74.

Roman GC, Ghassabian A, Bongers-Schokking JJ et al. Association of gestational maternal hypothyroxinemia and increased autism risk. Ann Neurol 2013;74:733–42.

Getahun D, Rhoads GG, Fassett MJ et al. Accuracy of reporting maternal and infant perinatal service system coding and clinical utilization coding. J Med Stat Inform 2013;1:1–3. http://www.hoajonline.com/medicalstat/2053-7662/2051/2053.

Andrade SE, Scott PE, Davis RL et al. Validity of health plan and birth certificate data for pregnancy research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:7–15.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.. ACOG practice bulletin. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Number 37, August 2002. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002;79:171–80.

Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S et al. Autism diagnostic observation schedule: a standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord 1989;19:185–212.

Getahun D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K et al. In utero exposure to ischemic-hypoxic conditions and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2013;131:e53–61.

Coleman KJ, Lutsky MA, Yau V et al. Validation of autism spectrum disorder diagnoses in large healthcare systems with electronic medical records. J Autism Dev Disord 2015;45:1989–96.

Wei LJ, Lin DY, Weissfeld L . Regression analysis of multivariate incomplete failure time data by modeling marginal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc 1989;84:1065–73.

Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Peltier MR et al. Association of perinatal risk factors with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Perinatol 2017;34:295–304.

Aoki Y, Belin RM, Clickner R, Jeffries R, Phillips L, Mahaffey KR . Serum TSH and total T4 in the United States population and their association with participant characteristics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2002). Thyroid 2007;17:1211–23.

Krassas G, Karras SN, Pontikides N . Thyroid diseases during pregnancy: a number of important issues. Hormones 2015;14:59–69.

Robinson EB, Lichtenstein P, Anckarsater H, Happe F, Ronald A . Examining and interpreting the female protective effect against autistic behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:5258–62.

Dworzynski K, Ronald A, Bolton P, Happe F . How different are girls and boys above and below the diagnostic threshold for autism spectrum disorders? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51:788–97.

Giedd JN, Snell JW, Lange N et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of human brain development: ages 4-18. Cereb Cortex 1996;6:551–60.

Allen LS, Richey MF, Chai YM, Gorski RA . Sex differences in the corpus callosum of the living human being. J Neurosci 1991;11:933–42.

Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D et al. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:823–828.

de Cock M, Maas YG, van de Bor M . Does perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors induce autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders? Rev Acta Paediatr 2012;101:811–818.

Taylor PN, Okosieme OE, Murphy R et al. Maternal perchlorate levels in women with borderline thyroid function during pregnancy and the cognitive development of their offspring: data from the Controlled Antenatal Thyroid Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:4291–8.

Volk HE, Hertz-Picciotto I, Delwiche L, Lurmann F, McConnell R . Residential proximity to freeways and autism in the CHARGE study. Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:873–7.

Raz R, Roberts AL, Lyall K et al. Autism spectrum disorder and particulate matter air pollution before, during, and after pregnancy: a nested case-control analysis within the Nurses' Health Study II Cohort. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:264–70.

Roberts EM, English PB, Grether JK, Windham GC, Somberg L, Wolff C . Maternal residence near agricultural pesticide applications and autism spectrum disorders among children in the California Central Valley. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115:1482–9.

Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Just AC et al. Gestational exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and reciprocal social, repetitive, and stereotypic behaviors in 4- and 5-year-old children: the HOME study. Environ Health Perspect 2014;122:513–20.

Ibhazehiebo K, Iwasaki T, Kimura-Kuroda J, Miyazaki W, Shimokawa N, Koibuchi N . Disruption of thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription and thyroid hormone-induced Purkinje cell dendrite arborization by polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:168–75.

Fatemi SH, Halt AR, Realmuto G et al. Purkinje cell size is reduced in cerebellum of patients with autism. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2002;22:171–5.

Petreas M, She J, Brown FR et al. High body burdens of 2,2',4,4'-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47) in California women. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111:1175–9.

Peltier MR, Koo HC, Getahun D, Menon R . Does exposure to flame retardants increase the risk for preterm birth? J Reprod Immunol 2015;107:20–5.

Chen L, Wang C, Cui C et al. Prenatal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and birth outcomes. Environ Pollut 2015;206:32–7.

Clinical Practice Guideline Kaiser Permanente Southern California Preventive Services for Children and Adlolescents, 2013. (http://cl.kp.org/pkc/scal/cpg/cpg/html/PrevSvcsChild.html.) PMCID Accessed 20 June 2016.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 148: thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:996–1005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Statement of Financial Support

This study is supported by Kaiser Permanente Direct Community Benefit Funds.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Getahun, D., Jacobsen, S., Fassett, M. et al. Association between maternal hypothyroidism and autism spectrum disorders in children. Pediatr Res 83, 580–588 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2017.308

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2017.308

This article is cited by

-

Association of maternal levothyroxine use during pregnancy with offspring birth and neurodevelopmental outcomes: a population-based cohort study

BMC Medicine (2022)

-

A profile and review of findings from the Early Markers for Autism study: unique contributions from a population-based case–control study in California

Molecular Autism (2021)

-

Maternal iodine status in a multi-ethnic UK birth cohort: associations with autism spectrum disorder

BMC Pediatrics (2020)