Abstract

Background:

We aim to investigate the detailed associations between allergic diseases with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) among children.

Methods:

Clinical information from 2,896 children enrolled in the Taiwan Children Health Study was obtained for analyses. Allergic diseases, including atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, have been evaluated based on the questions adjusted from International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham questionnaire was used to assess symptoms of ADHD and ODD. Symptoms of depression, stress, and poor sleep quality were evaluated as the interactive risk factors.

Results:

Children having symptoms of allergic diseases within the past 1 y were associated with having all dimensions of symptoms of ADHD and ODD. Children with ever having a physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis were associated with inattentive and hyperactive–impulsive symptoms of ADHD. Ever diagnosed asthma was associated with ADHD and ODD. Ever diagnosed allergic rhinitis was associated with inattentive and combined symptoms of ADHD and ODD.

Conclusion:

Children with allergic diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, were associated with exhibiting ADHD and ODD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Allergic diseases, including atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, are common chronic illnesses in children, and their prevalence has increased markedly over the past decade (1). Associated symptoms may interfere with daily life and the sleep quality of affected children (2), leading to mental health and behavioral problems (3). An increase in the prevalence of childhood behavioral disorders has paralleled that of allergic diseases. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common and impairing childhood neuropsychiatric disorder (4,5). Clinically, ADHD often coexists with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (6), one of the most common behavioral disorders found in children and adolescents. Children with ODD show an ongoing pattern of extreme negativity, hostility, and defiance lasting for at least 6 mo. Without appropriate management, ODD may progress to conduct disorder, law-breaking and illicit substance usage.

Allergic and behavioral diseases may share a multifactorial pathophysiology, such as genetic factors, chronic inflammation, or environmental factors. A positive correlation between allergic diseases and ADHD has been reported in several clinical studies (7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). Most of the studies focused on the relationship between ADHD and a specific allergic disease, namely, atopic dermatitis (8,9,10) or asthma (7,11,13). Few studies discussed the relationship between allergic rhinitis and mental health problems (14). The presence of behavioral disorders may differ among the three major allergic diseases. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between allergic diseases (atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis) and childhood behavior disorders (ADHD and ODD), based on the hypothesis that allergic diseases may be an exacerbating factor or a potential cause of behavioral disorders. We also investigated important psychological problems, including depression, stress, and poor sleep quality, to identify whether these had interacting effects on the relationships between childhood allergic diseases and psychological behavior disorders.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

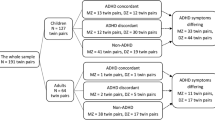

A total of 3,246 parent questionnaires (response rate = 87.7%) and 3,208 children questionnaires (response rate = 86.7%) were returned. After combining the parent and children questionnaires by subject identification number, we retrieved the data of 2,896 subjects for further analyses. All subjects were of Han Chinese ethnic origin. There were 1,463 boys (50.5%) and 1,433 girls (49.5%). The majority of participants were 10 y of age and from households with low to middle parental educational levels.

The Prevalence of Allergic Diseases and ADHD-Related Behavioral Disorders

The overall prevalence rates of lifetime physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis were 9.1%, 9.7%, and 31.6%, respectively. The prevalence rates of active atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis were 7.0%, 3.0%, and 19.9%, respectively ( Table 1 ). The prevalence of ADHD symptoms was 6.1%, with attentive, hyperactive–impulsive, and combined symptoms of ADHD divided into 3.0%, 4.6%, and 2.2%, respectively. The prevalence of ODD symptoms was 2.9% of the participants.

Main Effects of Allergic Diseases on ADHD-Related Behavioral Disorders

Logistic-regression models were created for each subscale of behavioral disorders to control for known confounders. As shown in Table 2 , children with active allergic diseases were associated with having all dimensions of symptoms of ADHD and ODD. Children who had ever been diagnosed with atopic dermatitis had higher odds of developing inattentive ADHD (odds ratio (OR) 2.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.44–3.32), hyperactive–impulsive ADHD (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.02–2.14), and ODD (OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.08–2.72). Children who had ever been diagnosed with asthma had higher odds of having symptoms of inattentive ADHD (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.26–2.46), hyperactive–impulsive ADHD (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.29–2.20), combined ADHD (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.10–2.45), and ODD (OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.34–2.56). Children who had ever been diagnosed with allergic rhinitis had higher odds of having symptoms of inattentive ADHD (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.10–1.82), combined ADHD (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.37–2.45), and ODD (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.06–1.75).

Interaction of Depression, Stress, and Poor Sleep With Allergic Diseases

Children with depressive mood had a higher OR to meet the criteria of ADHD and ODD, with an OR ranging from 2.12 to 4.03, which was statistically significant in all aspects. Children with high stress above the median did not show a significant association with symptoms of ADHD and ODD. Children with poor sleep quality had a higher OR to meet the criteria of ADHD and ODD, with an OR ranging from 2.48 to 3.35, which was statistically significant in all aspects. The interactions of depression, stress, and poor sleep quality with the relationships between each allergic diseases and ADHD/ODD are displayed in Table 3 . Stress and depression interacted with the relationship between atopic dermatitis and ADHD/ODD. Stress interacted with the relationship between asthma and ADHD/ODD. Depression and poor sleep quality especially affected the relationship between asthma and inattentive ADHD. Stress and poor sleep quality interacted with the relationship between allergic rhinitis and combined ADHD.

Joint Effects of Depression, Stress, or Poor Sleep and Allergic Diseases

The joint effects of depression, stress, and poor sleep and allergic diseases are displayed in Table 4 . Children with depression and either asthma or allergic rhinitis had higher odds of exhibiting symptoms of ADHD and ODD. Children with stress and one of the allergic diseases had higher odds of having symptoms of ADHD and ODD. Children with poor sleep quality and atopic dermatitis had higher odds of coexisting of ADHD, while those who with poor sleep quality and either asthma or allergic rhinitis had higher odds of coexisting of both ADHD and ODD.

Discussion

The current population-based epidemiologic study demonstrated the associations between allergic diseases and ADHD-related behavioral disorders. Different allergic diseases were associated with different subtypes of ADHD and ODD. We observed the highest effects of active atopic dermatitis with inattentive ADHD and active allergic rhinitis with combined ADHD. The odds for ADHD-related behavioral disorders increased synergistically when children had both allergic diseases and psychological problems including depression, stress, and poor sleep.

The associations between allergic diseases and mental health disorders, including ADHD, conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety, have been increasingly recognized (3,8,11,14,15). The mechanisms underlying the relationship between allergic diseases and mental health disorders, however, remain uncertain. The temporal relationship between atopic dermatitis and ADHD has been studied, revealing that infants with atopic dermatitis are at an increased risk for mental health problems at 10 y of age (9). One meta-analysis study demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between allergic diseases and mental health symptoms (17). Identifying genetic networks, behavioral processes, and gene–environmental interactions will provide insights into the complex relationships among allergic diseases and ADHD-related behavioral disorders.

Different dimensions of ADHD are associated with different developmental courses, comorbid disorders, sex ratios, and forms of functional impairment. Hyperactive–impulsive symptoms strongly correlate with Children’s Global Assessment Scores, and inattentive symptoms are related to academic impairment. Further analysis has revealed that both combined and inattentive types of ADHD are associated with significant social impairment (18). In this study, we observed that children with atopic dermatitis had higher odds of developing inattentive ADHD and ODD. Children who had ever been diagnosed with allergic rhinitis had higher risks of having inattentive and combined ADHD. A previous study had shown that only inattention symptoms (but not hyperactivity symptoms) were associated with allergic rhinitis (19), which is in agreement with the observations of our study. It has been demonstrated that asthmatic children exhibit more symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity in adolescence than controls (11). Deconstructing global assessments of ADHD into component subtypes may promote our analysis and understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relationships among allergic diseases and behavioral disorders.

In this study, we investigated the interaction of three psychological problems with the relationships between allergic diseases and ADHD-related psychiatric problems. Problems with depression in patients with bronchial asthma have been reported in the literature (20). Depression plays a major role in children’s internalizing disorder. The transformation between internalizing and externalizing behavior through childhood may occur. In our study, depression appeared to significantly influence the relationships between asthma and inattentive ADHD and also between atopic dermatitis and ADHD/ODD. Children experience stress from multiple sources, both internal and external. To cope with stressors, some children reported using aggressive behaviors. We observed that in children faced with stress that exceeded the adaptive resources of an individual and social system. We observed stress interacted between allergic diseases and ADHD/ODD. Sleep disturbances accompanying allergic disorders may predispose to psychiatric disorders and strengthen the association between allergic disorders and mental health conditions. One cross-sectional study reported that the association of ADHD and atopic dermatitis was modified by sleep disturbance in a large population-based sample (14). Some authors have argued that night-time asthma disturbances are related to poor sleep quality (21). The symptoms of allergic rhinitis also affect sleep quality, which results in daytime fatigue and cognitive and memory impairment. In our study, inadequate sleep appeared to significantly influence the relationships between asthma and inattentive ADHD and between allergic rhinitis and combined ADHD.

Compared with previous studies, the strength of this study is that the confounding effects of age, gender, parental marital status, socioeconomic status, prenatal tobacco exposure, and preterm status on ADHD symptoms have been adjusted in logistic regression models. It has been documented that parental marital conflicts (22), low socioeconomic status (23), household second-hand smoke or prenatal tobacco exposure (24), and preterm birth are related to ADHD or ODD. However, two limitations of this study deserve discussion. First, allergic diseases and ADHD-related behavior disorders were ascertained using questionnaires. Nevertheless, the relationships between allergic diseases and behavioral disorders were consistent with those reported in the literature. The questionnaires we used have been validated and widely used in epidemiologic studies. Second, under the design of a cross-sectional survey, this study can only demonstrate trends in associations, but not causal relationships. As the Taiwan Children Health Study is an ongoing cohort study, future investigations in this cohort may be helpful in elucidating the causal effects between allergic diseases and ADHD/ODD.

Uncontrolled ADHD and ODD may result in several complications, including the persistence of symptoms into adolescence or adulthood, poor social skills, depression, or even criminal activity (25). Accordingly, more comprehensive care should be offered to these children, their parents, and other caregivers (26). Whether good control of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis could provide favorable control of mental health disorders, or whether psychological interventions could ameliorate symptoms of allergic diseases was undetermined. Further longitudinal study may provide more information about it.

Children with allergic disease, such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, may have higher odds of developing different subtypes of ADHD-related behavioral disorders. The odds for ADHD-related behavioral disorders increased synergistically when these children had both allergic diseases and psychological problems including depression, stress, and poor sleep. In addition to physical discomfort, allergic diseases may also be related to psychiatric and behavioral problems.

Methods

The Study Population

We performed a cross-sectional analysis using the baseline data from Taiwan Children Health Study cohort, which is a nationwide multidisciplinary study investigating the influence of common environmental factors on allergic diseases and mental health problems in children (27,28). Since 2010, a total of 3,700 fourth-grade children (aged 9–10 y old) were enrolled in this cohort (cohort 2) from 14 different Taiwanese communities. After informed consent was obtained from both parents and children, the participants and their parents completed a written questionnaire, which included demographic information, socio-demographic factors, household environmental exposures, child behaviors, and allergic diseases. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital.

Evaluation of Allergic Diseases

All of the questions regarding allergic diseases were based on the standardized questions in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Atopic dermatitis was measured by the questions: “Has your child ever been diagnosed as having atopic dermatitis by a physician?” “Has your child had an itchy rash that was coming and going for at least six months? Did the itchy rash occur in the folds of the elbows, behind the knees, in front of the ankles, under the buttocks, or around the neck, ears or eyes within the last year?” Asthma was measured by using the questions: “Has your child ever had been diagnosed as having asthma by a physician?” “Has your children had an asthma attack within the last year?” Allergic rhinitis was assessed by asking: “Has your child ever had been diagnosed as having allergic rhinitis by a physician?” “Has your children had sneezing, running nose, or nose issues when not having a cold within the last year?” The questions answered were marked as “ever having a disease,” which means ever having a physician-diagnosed disease in the child’s lifetime. Having a “disease within the last year” was marked if both of the two questions in each allergic disease were “yes.”

Evaluation of ADHD and ODD

Parents were requested to complete questionnaires pertaining to their children’s behavioral and emotional problems using the SNAP-26. The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) questionnaire was developed in 1983, and the original SNAP-IV (43 items) was shortened to 26 items in the Multisite Multimodal Treatment Study for ADHD (The MTA Cooperative Group) in 1999 (29). In this study, we used the Chinese version of the SNAP-26 questionnaire (30). It consists of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV symptoms for the inattention (Items 1–9) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Items 10–18) criteria for ADHD and the oppositional symptom (Item 19–26) criteria for ODD. If the SNAP-26 inattention, hyperactivity, or combined subscale was equal to or higher than the cutoff score, participants were defined as having symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, or combined ADHD. If the participants belonged to any of the aforementioned categories, he or she was defined as having ADHD. Additionally, they were defined as having ODD by the same rule.

Assessment of Depression, Stress, and Sleep Problems

To evaluate the symptoms of depression in the participants, we used the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale questionnaire (31). CES-D is a structured questionnaire used to assess depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance. In our study, a CES-D cutoff score of 16 or higher (≥16) was set to define depression. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the CES-D questionnaire was 0.87. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (32) was used to quantify the stress perceived by the participants. Children were requested to answer the 14 items of the PSS. A PSS-14 score equal to or higher than 29, which was the median value among the participants of this study, was labeled as “high stress.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the PSS questionnaire was 0.40. To assess sleep problems, we used the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire (33). PSQI is a simplified tool for evaluating sleep quality within the most recent 1 mo, including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction (34). If the sum of the scores for the seven components was equal to or higher than 7, the participant was regarded as having “poor sleep quality.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the PSQI questionnaire was 0.60.

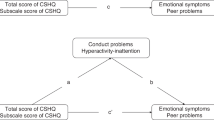

Statistical Analysis

SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the statistical analysis. The independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used to study continuous variables, and the χ2 test was used to study categorical variables. Stepwise logistic regression was used to establish predictive models, and the main effects of allergic diseases (atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis) on psychiatric behavioral disorders (ADHD and ODD) were explored. The PROC MI procedure method was used in SAS program that creates multiply imputed data sets for incomplete data. Our data were reduced bias and increased precision by the method and specify the Markov chain Monte Carlo. After the main effects of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis were validated, psychotic factors, such as depression, stress, and poor sleep quality, were further analyzed to investigate the interaction effects.

Statement of Financial Support

This study was partially supported by grants #98-2314-B-002-138-MY3 and #96-2314-B-006-053 from the Taiwan National Science Council.

Disclosure

The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al.; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733–43.

Baiardini I, Braido F, Cauglia S, Canonica GW. Sleep disturbances in allergic diseases. Allergy 2006;61:1259–67.

Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:428–33.

Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World Psychiatry 2003;2:104–13.

Gau SS, Chong MY, Chen TH, Cheng AT. A 3-year panel study of mental disorders among adolescents in Taiwan. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1344–50.

Gau SS, Ni HC, Shang CY, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity among children and adolescents with and without persistent attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:135–43.

Blackman JA, Gurka MJ. Developmental and behavioral comorbidities of asthma in children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007;28:92–9.

Schmitt J, Romanos M, Schmitt NM, Meurer M, Kirch W. Atopic eczema and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. JAMA 2009;301:724–6.

Schmitt J, Apfelbacher C, Chen CM, et al.; German Infant Nutrition Intervention plus Study Group. Infant-onset eczema in relation to mental health problems at age 10 years: results from a prospective birth cohort study (German Infant Nutrition Intervention plus). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:404–10.

Schmitt J, Chen CM, Apfelbacher C, et al.; LISA-plus Study Group. Infant eczema, infant sleeping problems, and mental health at 10 years of age: the prospective birth cohort study LISAplus. Allergy 2011;66:404–11.

Mogensen N, Larsson H, Lundholm C, Almqvist C. Association between childhood asthma and ADHD symptoms in adolescence—a prospective population-based twin study. Allergy 2011;66:1224–30.

Schmitt J, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Roessner V. Is atopic disease a risk factor for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? A systematic review. Allergy 2010;65:1506–24.

Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown R. ADHD and health services utilization in the national health interview survey. J Atten Disord 2009;12:330–40.

Romanos M, Gerlach M, Warnke A, Schmitt J. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and atopic eczema modified by sleep disturbance in a large population-based sample. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:269–73.

Chang HY, Seo JH, Kim HY, et al. Allergic diseases in preschoolers are associated with psychological and behavioural problems. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2013;5:315–21.

Tsai CJ, Chou PH, Cheng C, Lin CH, Lan TH, Lin CC. Asthma in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2014;26:254–60.

Chida Y, Hamer M, Steptoe A. A bidirectional relationship between psychosocial factors and atopic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2008;70:102–16.

Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, et al. DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1673–85.

Lee YS, Kim SH, You JH, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder like behavioral problems and parenting stress in pediatric allergic rhinitis. Psychiatry Investig 2014;11:266–71.

Coban H, Aydemir Y. The relationship between allergy and asthma control, quality of life, and emotional status in patients with asthma: a cross-sectional study. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2014;10:67.

Tran BW, Papoiu AD, Russoniello CV, et al. Effect of itch, scratching and mental stress on autonomic nervous system function in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90:354–61.

Luyster FS, Teodorescu M, Bleecker E, et al. Sleep quality and asthma control and quality of life in non-severe and severe asthma. Sleep Breath 2012;16:1129–37.

Harvey EA, Metcalfe LA, Herbert SD, Fanton JH. The role of family experiences and ADHD in the early development of oppositional defiant disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:784–95.

Nomura Y, Marks DJ, Grossman B, et al. Exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus and low socioeconomic status: effects on neurocognitive development and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:337–43.

Tsai CH, Huang JH, Hwang BF, Lee YL. Household environmental tobacco smoke and risks of asthma, wheeze and bronchitic symptoms among children in Taiwan. Respir Res 2010;11:11.

Chida Y, Steptoe A, Hirakawa N, Sudo N, Kubo C. The effects of psychological intervention on atopic dermatitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2007;144:1–9.

Chen YC, Chen PC, Hsieh WS, Portnov BA, Chen YA, Lee YL. Environmental factors associated with overweight and obesity in taiwanese children. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:561–71.

Chen YC, Tu YK, Huang KC, Chen PC, Chu DC, Lee YL. Pathway from central obesity to childhood asthma. Physical fitness and sedentary time are leading factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1194–203.

Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, et al. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:168–79.

Gau SS, Shang CY, Liu SK, et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham, version IV scale—parent form. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2008;17:35–44.

Chien CP, Cheng TA. Depression in Taiwan: epidemiological survey utilizing CES-D. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1985;87:335–8.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96.

Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1943–52.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, YT., Chen, YC., Gau, SF. et al. Associations between allergic diseases and attention deficit hyperactivity/oppositional defiant disorders in children. Pediatr Res 80, 480–485 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.111

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.111

This article is cited by

-

Association of atopic dermatitis with delinquent behaviors in US children and adolescents

Archives of Dermatological Research (2022)

-

Characteristics of childhood allergic diseases in outpatient and emergency departments in Shanghai, China, 2016–2018: a multicenter, retrospective study

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

Evaluation of neuropsychiatric comorbidities and their clinical characteristics in Chinese children with asthma using the MINI kid tool

BMC Pediatrics (2019)

-

Allergic Rhinitis and Other Atopic Diseases in Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Current Treatment Options in Allergy (2018)

-

In response to Letter regarding “Revision adenoidectomy in children: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan”

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2017)