Abstract

In November 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics convened key stakeholders to discuss the feasibility of accelerating children’s medical advances by creating an independent global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network. The Forum identified challenges posed by the US and global clinical trial systems regarding testing and disseminating drugs and devices for pediatric patients. Stakeholders mapped a vision to improve the safety and efficacy of pediatric drugs, biological products, and medical devices by creating a global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network. Such a Network would act as a central infrastructure for pediatric subspecialties and enable dedicated staff to provide clinical research sites with scientific, medical, and operational support. A Network would facilitate development and availability of innovative, high-quality therapies to extend and enhance the lives of neonates, infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. Participants expressed strong interest in forming such a Network, since drugs and devices still come to market without adequate pediatric indications—particularly in neonatology and rare diseases. Participants developed a Consensus Statement expressing their shared vision for a Network: Attendees of the Pediatric Clinical Trials Stakeholder Forum resolved to establish a Global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network and are committed to engage in the work to create and sustain it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Overview

On 4–5 November 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) convened a diverse group of key stakeholders for a Pediatric Clinical Trials Stakeholder Forum. The Forum brought together an unprecedented number of leaders with diverse backgrounds and interests, including clinicians, academicians, regulators, families and patient advocates, AAP leadership, and representatives from the pharmaceutical industry as well as from other focused disease Networks. Figure 1 is a photograph of the world experts in pediatric pharmacology and pediatric clinical trials who assembled for the AAP Pediatric Clinical Trials Stakeholders’ Forum.

Participants of the AAP Pediatric Clinical Trials Stakeholders’ Forum.

The meeting’s goal was to discuss the feasibility of accelerating medical advances for children by creating an independent Pediatric Clinical Trials Network. The desired outcome was to address the challenges currently posed by the US and global clinical trial system and processes with respect to testing and disseminating drugs and devices for pediatric patients—and thereby to improve the safety and efficacy of pediatric drugs, biological products, and medical devices.

The Challenge

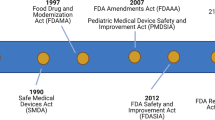

The “Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act” was enacted in 2012 to renew and strengthen laws designed to improve the safety and efficacy of pediatric drugs, biological products, and medical devices used in children. The Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act made permanent both the “Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act” and the “Pediatric Research Equity Act,” which are no longer subject to reauthorization every 5 y. (Similar policies have been put in place in the European Union and Canada; Japan and China are currently considering such legislation.)

These changes ensure that children have a permanent seat at the table for drug and device research and development, and the effects are already being seen. Pediatric studies spurred by this legislation have already provided important information to guide children’s clinical care. As of August 2014, studies submitted in response to US legislative initiatives have resulted in 527 changes in product labels relevant to children.

Despite these advances, significant barriers remain. Since 2007, more than half (60%) of the studies mandated by the US law have not initiated enrollment due to a variety of scientific, ethical, and operational challenges. Figure 2 illustrates the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) “Annual Pediatric Post-marketing Requirements Summary,” which reflects Center for Drug Evaluation and Research as well as Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research studies (1). (Note that pediatric studies released, fulfilled, or with a due date prior to FDA Amendments Act’s enactment are not included in the chart. The sharp decrease in the number of delayed studies is due, in large part, to the number of these same studies were subsequently converted to a status of pending or ongoing.)

FDA annual pediatric postmarketing requirements summary. The description of terms used in the figure is as follows: Pending: Study has not been initiated (i.e., no subjects have been enrolled or animals dosed) but does not meet the criterion for delayed (i.e., the original projected date for initiation of patient accrual or initiation of animal dosing has not passed). On-going: Study is proceeding according to, or is ahead of, the original schedule. The FDA considers a study to be on-going until a final study report is submitted to the agency, as long as the activities proceed according to the original study schedule. If patient accrual or animal dosing has started but is incomplete, and the projected date for completion of that milestone has passed, the study should be categorized as “delayed.” Submitted: Applicant has concluded or terminated the study and submitted a final study report to the FDA, but the agency has not yet notified the applicant in writing that the study commitment has been fulfilled or the commitment been released. Fulfilled: Applicant has submitted the final study report for the commitment and the FDA is satisfied the applicant has met the terms of the commitment. Released: FDA has informed the applicant that it has been released from its obligation to conduct the postmarketing study because the study is either no longer feasible or would not provide useful information. Delayed: Progression of the study is behind the original study schedule. Delays can occur in any study phase, including patient enrollment, analysis of results, or submission of the final study report. (The sharp decrease in the number of delayed studies is due, in large part, to the number of deferral extensions granted under FDASIA. Many of these same studies were subsequently converted to a status of “pending” or “ongoing.”) Terminated: Applicant ended the study before completion, and has not yet submitted a final study report to the FDA. FDASIA, Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act.

These data summarize information submitted by applicants about their progress in conducting pediatric studies. The sharp decrease in the number of delayed studies stems, in large part, to the number of deferral extensions granted under Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act. After receiving deferral extensions, many of these studies were subsequently converted to a status of “pending” or “on-going.”

A comparison of the adult and pediatric clinic trials for the same indication of systemic hypertension is provided by fosinopril studies. The adult fosinopril trial enrolled 220 adult patients in nine US sites (an average of 24 patients per site) and completed the efficacy study in 5 mo. The pediatric study, in comparison, enrolled 253 pediatric patients aged 6 to 16 y in 70 sites, in three countries (an average of 3.5 patients per site), and required 1 y for completion.

As a result of these challenges, many drugs and devices are brought to market without pediatric indications and pediatric-specific labeling. The FDA notes that, “As of 2008, an estimated 50–60% of prescription drugs used to treat children have been studied in some part of the pediatric population. Still, the likelihood that a medicine has actually been studied in neonates—children less than a month old—is close to zero” (2,3). Only 17 products have received approved pediatric formulations under the US law since 2007 (4), and only 1 product label change (for sodium nitroprusside) has been made for off-patent medicines since that year (5). (The National Institutes of Health funded the Pediatric Trials Network in an effort to address this issue.)

In addition, a median of 9 y passes between the approval of medicines for adult use and the inclusion of pediatric data in product labels. The same situation occurs with pediatric-specific devices, medicines, procedures, and other interventions where robust data are required to support regulatory approval for pediatric use and to guide informed decision making in clinical practice.

Sadly, the pathway and process for conducting clinical trials in the United States currently fails to optimize or accelerate medical advances for children. The current situation, which is characterized by stakeholders working in isolated silos, is far from optimal.

Efforts to improve this situation face methodological, ethical, regulatory, and operational challenges, including:

-

Lack of dedicated pediatric clinical investigator sites, infrastructure, and trained personnel to support pediatric clinical research—which results in long start-up times and recruitment challenges.

-

Poor and/or infeasible pediatric clinical study designs with a lack of validated end points.

-

Increasing financial costs, including inadequate per-study costs given the small numbers of patients to be enrolled per site.

-

Limited public awareness and understanding about the importance of providing well-studied drug therapies for children (especially newborns).

-

Need for data to be of sufficient caliber and detail to comply with regulatory submission standards and support rigorous review.

-

Lack of suitable and stable infrastructure for therapeutic studies, which results in building site infrastructures to support individual studies, dismantling them when studies are completed, and rebuilding them again when studies are initiated at a later time.

Addressing these challenges requires all children’s health stakeholders to move beyond the current fragmented and insular approach, create a shared new vision for pediatric clinical trials, and then collaborate to implement that vision. Such a vision would include a clear articulation of:

-

An improved, innovative approach to planning pediatric studies and the commensurate pediatric clinical trial infrastructure to perform those studies.

-

Timely development of age-appropriate formulations, evaluative tools, and biomarkers for the developmental continuum of the pediatric population.

-

Reduction of administrative barriers that hamper safe and efficacious products being assessed through clinical trials and accessed by the patients who need them.

-

More robust, publicly available data demonstrating the safety and efficacy of drugs and devices used in children that are communicated in a timely manner.

-

Shorter time frames between adult and pediatric labeling.

-

More integrative work across a variety of stakeholders.

The Solution: A Pediatric Clinical Trials Network

The creation of an independent Global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network would help address all of these challenges by creating a central infrastructure spanning all pediatric subspecialties and providing clinical research sites with scientific, medical, and operational support delivered by dedicated staff. These benefits would reduce administrative burdens and reduce the time needed to plan and complete studies, thereby making it more feasible to meet regulatory timelines.

A Network would help plan, establish, conduct, and complete studies to efficiently deliver the high-quality data that are required by regulatory standards and provide timely reviews. Its infrastructure would ensure that best practices are disseminated and built upon, rather than having to be rediscovered and reinvented with every new trial. It would enable early and continuous partnerships between children and their caregivers, academia, industry, government agencies, and families. While focused on the United States, a Global Network would enable communication and collaboration with other networks internationally.

A Network will facilitate the development of a global overview of therapeutic and scientific needs, statuses, and opportunities—and enable the establishment and maintenance of long-term extension studies and registries. It will help create an accessible pool of pediatric patients with specific diseases, thereby facilitating participant recruitment for clinical trials. A Global Network would enable stakeholders to examine therapeutic needs and prioritize their work based on accurate assessments of what research questions are feasible.

A Network would provide an international platform to unite key pediatric stakeholders in a public–private partnership that is centered around child health and is shared, systematic, efficient, credible, transparent, and comprehensive. It will reduce the risk that ineffective and/or unsafe therapies are prescribed to children. Most importantly, a Global Network would facilitate the development and availability of innovative, evidence-based, and high-quality therapies—according to the highest ethical and scientific standards—to help extend and enhance the lives of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults.

In 2014, Dr Woodcock, Director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, presented testimony to the US House of Representatives’ Energy & Commerce Committee on this issue. In her testimony, Dr Woodcock prioritized clinical trial networks as a way to foster faster development of new drugs, modernize biomedical innovation, and address barriers faced by developers in bringing drugs to market (6).

Dr Woodcock spoke to the Forum attendees, noting, “to answer the multiple and ever-evolving questions about drug therapy in children, an organized effort would be most efficient. It is certainly possible to create a clinical trial network that is capable of evaluating everything from pharmacokinetics at different age groups to pediatric formulations and conducting full-scale efficacy trials. Because such an organized effort would be much more cost effective than current one-off trials, the entire program could cost no more than what is currently being invested. The challenge will be to make this effort sustainable.”

She also made specific recommendations to respond to the ethical imperative for evidence-based pediatric treatment by developing a pediatric clinical trials network and her recommendations included:

-

Base the network on common standards. Tremendous underlying variability exists in pediatrics based on age, developmental stage, regional practice variations, etc. In the face of so much variation, it is prudent to reduce controllable, external sources of variability. After initial investment, standards-based data collection can also save both time and money. The Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium is a standards organization for clinical trial data; it has collaborated with the C-Path Institute to form the Coalition for Accelerating Standards and Therapies. This organization is developing disease-specific data standards and might have interesting lessons for a pediatric network.

-

Use modern technology, including Electronic Health Records. It is possible that much acquisition of clinical trial data could be conducted in the context of the care delivery process (with the exception of randomization and specialized testing).

-

Include community practices as part of research networks in order to increase the external validity of results and ensure adequate participation in clinical trials.

-

Ensure strong staff support and infrastructure, which are keys to ensuring sustainability. There needs to be enough staff at each site to maintain momentum and not rely on those who have other full-time jobs.

-

Start small; set up pilot projects and see what works.

-

Be pragmatic; most clinical trials use multiple site audits and conduct extensive “data cleanup” efforts, which may be unnecessary. The Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative is exploring “Quality by Design,” which seeks to “build” quality in rather than “inspect” it in. (The FDA and other regulatory authorities generally accept these approaches.)

-

Assess what data elements are really needed, especially since adult data are available in many cases. Academia and industry alike both generally collect excessive data during clinical trials, which can degrade the quality of the important data elements. Trails that focus on only essential data elements can actually be better; for example, the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI) trials collected minimal data elements, yet led to important FDA approvals.

-

Incorporate parents and patients from the start; they have important insights and can help keep the momentum going.

-

Write a business plan to gain a clear idea of the network’s feasibility.

Dr Woodcock closed by noting that children deserve evidence-based therapies. While much is being done under current circumstances, our country can do better and generate much more evidence if all stakeholders unite their forces. To accomplish this goal, concerned parties will need to put aside traditional practices and do things differently; the patients deserve no less.

Essential Components of a Network: Long-term Vision and Short-term Activities

Many of the Forum activities were devoted to discussing and specifying the activities needed to develop systems to ensure that a potential network could be both implemented and sustained.

The primary goal of the Stakeholder Forum was to answer key questions about establishing a Global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network: did the attendees agree that their representative organizations share a common vision and set of desirable outcomes, goals, and objectives to improve the system and process to advance pediatric care; did the attendees agree that the will exists to take the necessary steps to lead and implement change; and did the attendees agree that there are actionable opportunities (i.e., first steps) to support realization of these outcomes?

To guide this discussion, the Forum participants used a draft design proposal, which was developed over the 18 mo leading up to the Forum and offered a starting point for consideration of the long-term vision and short-term activities of a network. This draft design proposal reflected the ideas, requirements, and aspirations of more than 100 stakeholders from patient advocacy groups, academia, government, associations, foundations, and industry. The proposed design offered a “full-service” solution to facilitate collaboration and partnerships. Key structural components of the proposal were modeled after lessons learned from existing pediatric networks in order to reflect best practices.

In addition, before the Forum, 39 attendees completed a survey to provide feedback on four questions to guide the discussion:

-

1. What are the critical factors and challenges affecting the efficiency of pediatric drug development and clinical trials for innovative drugs and biologics?

-

2. In what areas would a pediatric clinical trial network create the most value?

-

3. What are the short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term measures of success for a pediatric clinical trial network?

-

4. What is the vision for the group’s mission?

The survey responses confirmed the sense that solutions are possible. Survey results demonstrated that participants have both the desire and commitment to create a Global Network and ensure it is operational as soon as possible.

Salient comments about the challenges, value, successful indicators, and vision of the network include the following:

-

“The greatest challenges are: developing strong working relationships between academics and industry; creating a culture of research participation among patients/families; and demonstrating that patients and families had positive experiences through participation [in clinical trials].”

-

“The greatest need is for one-stop shopping for investigators/sites/institutional review boards that have a mechanism to fast-track approval of protocols. From receiving a protocol, to enrolling the first patient should take only 2 w, not 4–6 mo. Agreement on review of the protocols should occur before they are accepted by the Network, so that when sites receive the protocols, there is pre-acceptance of the protocol by investigators, institutional review boards, etc.”

-

“For the group assembled by the AAP for this forum, my vision is that this group will: quickly come to agreement that a well-functioning clinical trials network is required to effect a substantial improvement in the evaluation of drugs and devices for use in children of all ages; identify area(s) that each of the diverse stakeholder groups will contribute to the network; and identify early wins for the network that will accelerate the network’s launch and success.”

Using this background work as a foundation to the proceedings, meeting participants were assigned to seven issue-oriented small groups, each of which addressed a critical function or operational aspect of a potential Network. The seven groups were: Patient Engagement and Advocacy; Pediatrics Research Education and Support; Improving Pediatric Study Science; Outcomes Research and Epidemiology; Pediatric Study Operations; Site Engagement and Advocacy; and Operating Model Considerations and Alternatives.

Members of these seven groups worked together to generate a summary of a Pediatric Clinical Trials Network’s essential elements, and craft both short- and long-term actions to accomplish these elements within the next year. These essential elements and immediate activities include:

-

1. Leadership team: Form an inclusive leadership team that includes representatives from the various stakeholder groups: patients, parents, community members, industry, academia, Children’s Hospitals, disease organizations, advocacy groups, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health (including the NIH’s Global Health Research Initiative), other regulators, and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The team will be accountable for creating and achieving clear and unambiguous deliverables.

-

2. Funding: Acquire seed funding for the entity and create a transparent funding model.

-

3. Plans: Draft a business plan and an operations plan that together direct the network’s actions and goals. These plans provide a clear sense of a network’s feasibility and align the interests of the sites and associated investigators, industry, parents/families, and regulators.

-

4. Incorporate the new entity: Create a new nonprofit entity that can lead, receive input from stakeholders, and facilitate communication among the various stakeholders (i.e., Food and Drug Administration and industry).

-

5. Other networks: Engage the many other existing networks in order to benefit from business analysis, lessons learned, and best practices.

-

6. Systems and standard operating procedures: Create systems including prioritization process for studies, centralized training and data collection structure, Data Safety Monitoring Board, parental/advocates’ involvement, single institutional review board, outreach plan, and conflict of interest policies.

-

7. Membership requirements and benefits: Create membership criteria for sponsors and sites, including their expected responsibilities, and enumerate the benefits of membership in the Network (i.e., study prioritization) for all types of sponsors.

-

8. Data warehouse: Lay the groundwork for a creation of a national Data Warehouse (driven by Electronic Health Records) and single Electronic Data Capture platform/provider with data-sharing agreements.

-

9. Momentum: The organizers were urged to build upon the momentum generated by the November meeting to create the Network. Suggested 6-mo goals include drafting a science plan and business plan and establishing the network’s core activities (i.e., site enrollment criteria, Master Service Agreement, legal review, etc.) to facilitate, within 1 y of initiating the Network, completing one trial and having four protocols underway.

Consensus Statement

There was a palpable sense of urgency at the Forum to move ahead with the global Network. Attendees agreed that their representative organizations share a common vision and set of desirable outcomes, goals, and objectives to improve the current system and collaborate on a process to advance pediatric care.

The wide variety of stakeholders agreed that such a network should exist to implement change and created a Consensus Statement to that effect. Officially stated: The attendees at the Pediatric Clinical Trials Stakeholder Forum resolved to establish a Global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network and are committed to engage in the work to create and sustain it.

Attendees identified key actions that build upon the expertise and commitment of the various stakeholders and advance the Network. The first step was to identify members of a transitional leadership team. It was noted that multiple stakeholders have expressed interest in supporting next steps with funding and that this funding could be used to form an infrastructure and oversight board to catalyze formation of business and operational plans to create the Network.

These are described in Table 1 and include:

-

Establish an advisory board (leadership team) with tactical, strategic, and operational functions; address ethics and safety.

-

Ensure creation of a strong organizational structure.

-

Protect leadership’ time and institutional support to ensure that a quality product results.

-

Engage a consultant to explore the legal, regulatory, and logistical elements of creating a transitional entity and eventual Network.

-

Decide on public–private partnership pathway (i.e., Limited Liability Corporation, foundation, etc.).

-

Create mechanisms for on-going operations (fee-for-service, membership fees, and grants).

-

Identify and quantify required seed money and on-going funding.

-

Ensure that the funding mechanism is transparent.

-

Build the transitional entity that will begin to work in conjunction with the Advisory Board.

-

Review and revise existing (draft) business plan and create a strong business plan.

-

Connect with existing networks, models, and parent groups to foster collaboration, gather feedback, and avoid recreating the wheel (i.e., use existing Standard Operating Procedures, etc.).

-

Create an operational plan that is transparent, specific, and available for input and critique (the network is held accountable to this plan).

-

Establish conflict of interest policies and standard operating procedures.

-

Create a master service agreement/contract; standardized budget templates; model institutional review board; metrics on data access.

-

Draft communications and public relations strategies and plans.

-

Create unambiguous deliverables with clear timelines and outcomes that can be measured and acted upon.

-

Define a clear path forward for the creation of the Board of Directors and the official Network entity.

-

Secure major funding for the Network.

Meeting participants expressed the critical need for children to have timely access to needed medications—including the same innovative and clinically relevant medical therapies that adults do—delivered in pediatric-suitable formulations. The Forum participants agreed that achieving medical advances and breakthroughs as rapidly as possible helps the greatest number of children and families attain and sustain health. There is also a need for more information about postmarketing and the long-term safety of products used in pediatrics. A global Pediatric Clinical Trials Network can help meet these needs and address challenges posed by the clinical trial systems with respect to testing and disseminating drugs and devices for pediatric patients.

Planning Committee

-

○ Clifford Bogue, MD, FAAP, Planning Committee Chair, Yale School of Medicine, Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital

-

○ Linda A. DiMeglio, MD, MPH, FAAP, Indiana University School of Medicine, Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health

-

○ Samuel Maldonado, MD, MPH, FAAP, Janssen Research & Development

-

○ Ronald J. Portman, MD, FAAP, Pediatric Therapeutic Area, Novartis Pharmaceuticals

-

○ P. Brian Smith, MD, MPH, MHS, FAAP, Duke University Medical Center

-

○ Janice E. Sullivan, MD, FAAP, Kosair Charities Pediatric Clinical Research Unit, University of Louisville

-

○ Charles Thompson, MD, FAAP, Pediatric Center of Excellence, Pfizer, Inc.

-

○ Heide Woo, MD, FAAP, Pediatric Research in Office Settings, University of California–Los Angeles

The Pediatric Clinical Trials Stakeholder Forum Planning Committee wishes to acknowledge the support of the AAP and its staff in the organization of the Forum and its proceedings: Jackie Burke; William Cull, PhD; Jonathan Klein, MD, MPH, FAAP; Raymond Koteras, MHA; and Ken Slaw, PhD.

The Planning Committee also wishes to acknowledge the hard work of the facilitator, Mr Matt Hendricks, Pharmica Consulting, and Ms Susan Flinn, Documentarian and Technical Editor.

We acknowledge the participation and insight of the meeting attendees, who not only served as content experts but also contributed to the meeting discussions, workgroups, ideas, and outcomes. A full list of participants is available from the corresponding author.

Forum Participants

-

○ Donna Appell, RN, Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome (HPS) Network; Parent Representative

-

○ Ronald Ariagno, MD, FAAP, AAP Section on Perinatal Pediatrics

-

○ Charles Bailey, Jr, MD, PhD, PEDSnet, The Children’s’ Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP)

-

○ Daniel K Benjamin, Jr, MD, FAAP, Pediatric Trials Network

-

○ David Bertoch, MHA, Children’s Hospitals Association

-

○ Susan M. Blaney, MD, FAAP, Children’s Oncology Group, Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital

-

○ John S. Bradley, MD, FAAP, Rady Children’s Hospital/UCSD

-

○ Gilbert Burckart, PharmD, US Food and Drug Administration, Office of Clinical Pharmacology (OCP)

-

○ Ira M. Cheifetz, MD, FCCM, FAARC, Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Clinical Trials Network

-

○ Michael Cohen-Wolkowiez, MD, FAAP, Duke Clinical Research Institute

-

○ Edward Connor, MD, MBE, FAAP, Clinical Research Alliance, LLC.

-

○ William Cull, PhD, American Academy of Pediatrics

-

○ J Michael Dean, MD, MBA, FAAP, Division of Pediatric Critical Care, University Of Utah School Of Medicine

-

○ Mark Del Monte, JD, American Academy of Pediatrics

-

○ Irmgard Eichler, MD, European Medicines Agency

-

○ Lindsey L. Elsaesser, Parent Representative

-

○ G. Alexander Fleming, MD, Kinexum

-

○ Debbie S. Gipson, MD, University of Michigan School of Medicine

-

○ Rashmi Gopal-Srivastava, PhD, NCATS, National Institutes of Health Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network

-

○ Robert J. Guidos, JD, US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

-

○ Sandra G. Hassink, MD, FAAP, President-Elect American Academy of Pediatrics; Department of Pediatrics, Nemours Children’s Health System

-

○ Sascha Haverfield, PhD, PhRMA

-

○ Steven Hirschfeld, MD, PhD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

-

○ Cynthia R. Jackson, DO, FAAP, Quintiles, Inc.

-

○ Anne K. Junker, MD, MICYRN, Canada

-

○ Frederick J. Kaskel, MD, FAAP, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, The Children’s Hospital, Montefiore Medical Center

-

○ Gregory L. Kearns, PharmD, PhD, FAAP, Division of Pediatric Pharmacology and Medical Toxicology, Pediatric Pharmacology Research Unit, Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics

-

○ Jonathan D. Klein, MD, MPH, FAAP, American Academy of Pediatrics

-

○ Raymond J. Koteras, MHA, American Academy of Pediatrics

-

○ Mary B. Leonard, MD, MSCE, Stanford Spectrum Child Health

-

○ Dianne Murphy, MD, FAAP, US Food and Drug Administration, Office of Pediatric Therapeutics

-

○ Hidefumi Nakamura, MD, National Center Child Health and Development, Japan

-

○ Kathleen Neville, MD, FAAP, AAP Committee on Drugs

-

○ Martin Offringa, MD, PhD, The Hospital for Sick Children, Child Health Evaluative Sciences Program, Toronto, Canada

-

○ Gail Pearson, MD, ScD, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Adult and Pediatric Cardiac Research Program, National Institutes of Health

-

○ Scott W. Powers, PhD, ABPP, Office for Clinical and Translational Research, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

-

○ Lee M. Sanders, MD, MPH, FAAP, Society for Pediatric Research

-

○ Pamela L. Simpkins, MBA, PMP, Janssen CHILD Pediatrics

-

○ Kenneth Slaw, PhD, American Academy of Pediatrics

-

○ William E. Smoyer, MD, FAAP, FASN, CTSA Consortium

-

○ Stephen P. Spielberg, PhD, MD, FAAP, Drug Information Association

-

○ Michael J. Spigarelli, MD, PhD, FAAP, Academia

-

○ Susan Swedo, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health

-

○ William V. Tamborlane, MD, T1DM Exchange

-

○ Melissa S. Tassinari, PhD, DABT, US Food and Drug Administration

-

○ Mark Turner MBChB, PhD, National Institute for Health Research, Clinical Research Network: Children, UK

-

○ Robert M. Ward, MD, FCP, FAAP, University of Utah

-

○ Andrew W. Womack, PhD, BIO

-

○ Janet Woodcock, MD, US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

-

○ Lynne Yao, MD, FAAP, US Food and Drug Administration

-

○ Anne Zajicek, MD, PharmD, FAAP, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Statement of Financial Support

Funding for this Forum and meeting proceedings was made possible by an unrestricted contribution from The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

Disclosure

L.A.D. has a consulting relationship with Sanofi-Aventis and Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. S.M. is employed by Janssen Research and Development. R.J.P. is employed by Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation. P.B.S. has a consulting relationship with Astellas Pharma US, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline plc, and Pfizer, Inc. J.E.S. has a clinical trials relationship with AbbVie, Inc., Amgen, AstraZeneca, plc, Baxter US, Bayer AG, BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cadence Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited, Forest Laboratories, Genzyme Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline plc, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Johnson & Johnson, KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Optimer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pfizer, Inc., Purdue Pharma, LP, Sanofi-Aventis Selexys Pharmaceuticals, Sucampo Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd., Trius Therapeutics, UCB, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals—these funds are paid to the University of Louisville and for expenses associated with conducting clinical trials and are not paid to her personally. C.T. has an employee and shareholder relationship with Pfizer, Inc. S.F. was paid as a consultant to the AAP to write the proceedings report and draft this special article. The remaining authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric studies – annual status summary, no date. (www.fda.gov/downloads/scienceresearch/specialtopics/pediatrictherapeuticsresearch/ucm308465.pdf.)

Food and Drug Administration. Consumer updates: giving drugs to children, 2015. (http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm164427.htm.)

Cuzzolin L, Atzei A, Fanos V. Off-label and unlicensed prescribing for newborns and children in different settings: a review of the literature and a consideration about drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2006;5:703–18.

Food and Drug Administration. Formulations: pediatric formulations in accordance with sections 505A(f)(6)(D) and 505B(f)(6)(F) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the FDA Amendments Act (FDAAA), 2014. (http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/ucm049872.htm.)

National Library of Medicine. NITROPRESS®: Sodium Nitroprusside Injection, solution, concentrate, 2014. (http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=bf27f0a9-e64b-492a-b08f-2448bf097988.)

The Pink Sheet. Karlin S. FDA’s Woodcock prioritizes trial networks as drug development solution, 2014. (http://www.focr.org/5-7-2014-pink-sheet-fda’s-woodcock-prioritizes-trial-networks-drug-development-solution.)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and appreciate the hard work of the members of the Planning Committee, who provided input into the organization and process for the Stakeholder Forum. They participated in the event itself, where they not only served as content experts but also contributed to the meeting discussions, workgroups, ideas, and outcomes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bogue, C., DiMeglio, L., Maldonado, S. et al. Special article: 2014 Pediatric Clinical Trials Forum. Pediatr Res 79, 662–669 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.255

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.255

This article is cited by

-

The future of pediatric research: European perspective

Pediatric Research (2017)

-

Moving toward a paradigm shift in the regulatory requirements for pediatric medicines

European Journal of Pediatrics (2016)