Abstract

The prevalence of childhood obesity has increased globally over the past three decades, with evidence of recent leveling off in developed countries. Reduction in the, currently high, prevalence of obesity will require a full understanding of the biological and social pathways to obesity in order to develop appropriately targeted prevention strategies in early life. Determinants of childhood obesity include individual level factors, including biological, social, and behavioral risks, acting within the influence of the child’s family environment, which is, in turn, imbedded in the context of the community environment. These influences act across childhood, with suggestions of early critical periods of biological and behavioral plasticity. There is evidence of sex and gender differences in the responses of boys and girls to their environments. The evidence that determinants of childhood obesity act at many levels and at different stages of childhood is of policy relevance to those planning early health promotion and primary prevention programs as it suggests the need to address the individual, the family, the physical environment, the social environment, and social policy. The purpose of this narrative review is to summarize current, and emerging, literature in a multilevel, life course framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity has increased globally over the past three decades, with more rapid increases recently occurring in low-income countries (1). In the United States, more than 30% of children are now overweight or obese (1), with evidence that the prevalence has leveled off (2). Children and adolescents are exhibiting obesity-related conditions such as type 2 diabetes, elevated blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and higher fasting insulin levels (3,4,5,6). In addition, childhood obesity predicts adulthood obesity and its known health consequences (7,8). Treatment of obesity is notoriously difficult, with weight loss rarely sustained in adults (9). Therapeutic interventions in childhood are somewhat more successful, particularly if the intervention occurs prior to onset of puberty (10). However, real and sustained progress in combating the obesity epidemic will require a full understanding of the biological and social pathways to obesity in order to develop appropriately targeted prevention strategies in early life.

Pathways to childhood obesity are complex. It is therefore helpful to discuss determinants of obesity within a conceptual framework. A multilevel conceptual model, Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Systems Theory (11), has previously been applied to the conceptualization of childhood obesity by Davison and Birch (12). This framework depicts individual-level factors, including biological, social, and behavioral risks, as acting within the influence of the child’s family environment, which is, in turn imbedded in the context of the community environment. It is also helpful to consider critical periods for obesity risk and, as will be further illustrated in a later section, there are likely critical periods of biological and behavioral plasticity beginning as early as fetal life (13) with risk factors accumulating, and interacting with each other, across the life course. This is consistent with a life course model of chronic disease epidemiology (14). Specific determinants of obesity will be discussed below within this multilevel framework and life course perspective.

This narrative review will discuss both biological and social determinants of childhood obesity at three levels (individual, family, and community) and across early childhood. The relationship between childhood stress and obesity will be explored in greater detail as this is an important pathway of active interest in current literature. In addition, the review will address recent attention to sex- and gender-based differences in obesity risk. A key purpose in undertaking this review was to summarize evidence regarding pathways to obesity in boys and girls by integrating established plus emerging perspectives in the literature. These include an overview of important factors at each level. Given the breadth of the literature, it was not the intention to cover all literature on each determinant but rather to provide these as key examples of the many dimensions of obesity risk.

Individual-, Family-, and Community-Level Determinants of Obesity

At the individual level, the most direct determinant of children’s obesity is the energy balance between nutritional intake and activity, the latter being influenced by both physical activity and sedentary behaviors (15,16,17). These behavioral factors are therefore frequent targets for both preventive and therapeutic interventions. However, nutrition and activity are “downstream” factors that can be influenced by many “upstream” causes. The energy balance required to maintain an appropriate fat mass varies among individuals due to differences in metabolism and in lipostatic set point, which will influence appetite and activity preferences (18). Metabolism and lipostatic set point, while to some degree influenced by genetic predisposition (18), can be altered by gene–environment interactions (19,20,21).

The family, physical, and social environment influence children’s obesity risk in two ways: through a direct influence on children’s nutrition and activity behaviors and through indirect influences via stress as will be discussed later in this paper. Higher parental education, parental nurturing, and higher self-esteem reduce obesity risk in girls (22). There is an abundance of evidence that the home food environment (23,24,25), shared family meals (26,27), and electronic media use influence children’s obesity (28) largely through behavioral pathways. Mothers primarily establish the home food environment and are role models for eating behaviors (29) with evidence of strong correlation between the eating patterns of mothers and children (25,29). Appetite control and food preferences are established early in life (30), and there is a high correlation between parental obesity and their children’s obesity (20,22).

The community environment is increasingly obesogenic, with increased use of convenience foods, automobiles, and electronic and televised forms of entertainment (31,32,33) leading to higher consumption of calorie-dense foods and more sedentary lifestyles. Food choices have been shown to be influenced by proximity to fast food outlets, supermarkets, and farmers markets (34,35,36,37,38). Physical activity levels are influenced by public recreation opportunities, transit availability, and neighborhood walkability (35,37,39,40,41,42). In addition, lower obesity levels are observed in areas where the natural environment has high recreational value (43). While evidence suggests that the above environmental factors affect risk behaviors and obesity, there is still a gap in understanding how children interface with the obesogenic environment (44).

Prenatal and Postnatal Influences

There is emerging interest in prenatal factors, postnatal factors, and their interactions. These are critical time periods of metabolic and endocrine plasticity and may condition later physiologic responses to environmental influences (13). This field of research has been labeled as the developmental origins of health and disease and is the subject of much attention in the biomedical and epidemiologic sciences.

For the past two decades, there has been intense interest in the possible effect of fetal undernutrition on later obesity. The interest in this proposed association was precipitated by seminal work by Barker (45). In humans, fetal undernutrition may be a consequence of maternal undernutrition, maternal smoking, or placental dysfunction from preeclampsia. Markers of fetal undernutrition, which include fetal growth restriction and its proxy indicator small birth weight for gestational age, have been shown to be associated with a modestly elevated risk of obesity. It has been suggested that this effect is due to an in utero adaptation that becomes a mismatch to a postnatal environment in which nutrition is abundant (46,47). Animal studies, often based on maternal dietary restriction, confirm evidence for such fetal metabolic adaptations to undernutrition (48). In both animal and human studies, there is evidence of the permanence of these adaptations. The greatest elevation in obesity risk is for those who were born small, but experienced rapid “catch up growth” postnatally (48,49,50,51,52).

Emerging literature is challenging the relationship of fetal undernutrition as a determinant of obesity. First, if the association does exist, is a genetic component partially responsible? Specific adult obesity gene loci have been implicated as associated both with fetal growth (53) and with growth velocity in infancy (54). In this genomic era, this will be an aspect of the literature to watch, although to date the predictive value of individual gene loci for obesity risk has been modest. There is emerging speculation as to whether this association indeed exists at all, despite the abundance of literature on the topic. Part of this speculation is based on a statistical argument that, in the zealous effort to control for the myriad of potential confounders, most studies looking at the relationship between fetal growth restriction or small birth weight for gestational age and later chronic conditions have controlled for variables along the causal pathway and thus introduced bias (55,56). Moreover, recent carefully analyzed studies have suggested the inverse; that small birth weight for gestational age is associated with a lower risk of obesity (57). This question remains an active topic of interest in the literature, despite the recognition that the association, if real, is a small magnitude association with no clear implications for prevention (58).

Fetal overnutrition, evidenced by large infant birth weight for gestational age, is a strong predictor of obesity in childhood and later life (59,60,61). A caveat is that, while large infant birth weight for gestational age is generally an indicator of excess fat mass, it may also reflect other growth parameters such that a subset of large infant birth weight for gestational age infants may have increased lean mass (62,63). Risk factors for large infant birth weight for gestational age include maternal obesity and maternal gestational diabetes (64,65) with African-American women exhibiting risk at lower maternal BMI thresholds (66). It is suggested that fetal hyperglycemia triggers fetal insulin production which in turn triggers fetal growth and adiposity (67). Animal studies demonstrate that fetal hyperinsulinemia may invoke permanent changes in the CNS mechanisms for regulating metabolism and body weight (67). Thus, fetal overnutrition may be a mechanism of intergenerational transmission of obesity and diabetes (67,68).

Early postnatal experiences are also important contributors to obesity risk. Breastfed infants are at lower risk for later obesity (69,70,71,72,73) for hypothesized reasons including that formula-fed infants develop greater reliance on external hunger cues (74) and have higher intake of protein (75), which may contribute to obesity risk through behavioral and physiologic mechanisms, respectively. The benefits of breastfeeding appear to be confined to exclusive breastfeeding; mixed infant feeding of breastmilk and formula do not reduce obesity risks associated with formula feeding (76). In addition, the timing and choice of complementary foods introduced into an infant’s diet may influence their food preferences in the long term (77). In general, obesity risk is elevated for those who experienced rapid early weight gain in infancy (78,79,80). Based on this knowledge, strategies for primary prevention in high-income countries may include support for long-term breastfeeding (81).

Psychosocial Vulnerabilities

There is evidence that psychosocial stress is associated with obesity in children. Measures of stress vary from study to study (82), but the findings are consistent. Whether this association is causal is not known, but there are theoretical frameworks that suggest causality. For example, the life course–stress process perspective introduced by Pearlin et al. (83) has been discussed by Wickrama et al. (84) in the context of body mass. A pathway from stress to obesity could include inflammatory mechanisms (85) including arousal of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis leading to increased cortisol levels and subsequent metabolic disruption and increased hunger (84,86,87,88). If so, nutrition may mediate the relationship between stress and obesity, or lifestyle factors may be coexisting with environmental stressors (89,90). Some of the reported associations of environmental stressors with childhood overweight and obesity include negative life events (82), maltreatment (91), how well the family communicates (90), and parental stress (92).

Depression and obesity are often comorbid in both children and adults. This comorbidity may be due to common genetic and environmental etiologies (93,94,95,96) or common pathways via dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system (93,95,96). Increased food intake and reduced physical activity are characteristic of both conditions (94). Bidirectional causation is also plausible, with suggestions that obesity may be a determinant of later depression in children (97,98,99) and conversely hypothesized mechanisms for depression causing obesity (93,95,98,99,100). Indeed, it has more recently been suggested that these two comorbid conditions may mutually reinforce a progressive downward spiral in each other (101) and that additional insight into their longitudinal interaction may be important for intervention strategies (102).

Mothers’ mental and emotional well-being has been shown to be associated with childhood obesity. Children of mothers with depressive symptoms are more likely to be obese or overweight in infancy (103,104), childhood (105,106), and adolescence (107). Prenatal exposure to maternal stress and distress has been shown to be associated with both children’s obesity and rapid postnatal growth (108,109). Proposed mechanisms for the association include infant feeding practices (110), mother–infant interaction (111), mother–infant feeding interactions (112), parenting style (113), and a direct effect of stressors leading to central adiposity via arousal of the child’s hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (86). It has also been suggested that, due to the comorbidity between maternal overweight and emotion regulation, these pathways may also play into the intergenerational transfer of overweight and obesity (112), as well as the roles of shared genes and environment (86). A recent systematic review noted the need for more prospective studies to confirm and explain these associations (114).

Consistently, in high-income countries, socioeconomic disadvantage has been shown to be associated with obesity risk in childhood and persistently throughout life (115,116,117). Socioeconomic disadvantage may exert its influence as early as the prenatal and postnatal period, through its association with maternal depression (106,118) and its consequences. Moreover, poverty may be associated with poorer individual diet (119), poorer retail food and recreational environment (34,120,121), suboptimal family food routines (118,122), and environmental stressors such as living in a higher crime neighborhood (121). The risks associated with socioeconomic disadvantage may accumulate and compound throughout childhood (123). Miller and Chen (124) present a theoretical model, with corresponding research evidence, linking poverty to the development of a proinflammatory phenotype and subsequent elevated risk for chronic conditions in childhood and beyond. Overall, it appears that poverty is associated with later obesity through its association with other obesity risk factors and through the stress process.

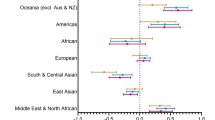

There is an increasing attention in the literature to the differences in vulnerabilities in boys and girls, suggesting different pathways to obesity. Much of the literature, to date, has looked at determinants of childhood obesity while statistically controlling for children’s sex. However, to truly understand the developmental processes leading to obesity, researchers may need to look at boys and girls separately in order to recognize both sex-specific (biological) and gender-specific (social and cultural) differences in the ways in which boys and girls interact with their physical and social environments. Some biological differences include body composition and growth patterns, with clear sex differences in the distribution of adiposity beginning as early as the neonatal period and continuing through adulthood (125). Energy requirements and the aptitude for specific physical activities exhibit sex differences, while specific gender differences include how boys and girls interact with their family and their food environment as well as their overall physical activity levels (126). There are also gender differences in metabolic responses to stress (87) and family disruption or conflict (127). Responses to the physical and social environment will influence, and be influenced by, pubertal development (47,48,125). Pubertal timing itself has significant influence on insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, particularly in girls (128,129). The pubertal transition is also well established as a time when depression rates rise dramatically, particularly for females; indeed, this developmental stage is when the gender difference in depression emerges (130,131). Finally, pubertal timing and growth influence later adult cardiovascular risk in both males and females (128). Additional research focusing on the gendered dimensions of childhood obesity is needed.

Summary and Implications

In undertaking a review of this broad area of significant health promotion interest, I have used the narrative review method. It has been argued that narrative reviews have advantages when the scope and literature coverage is broad and covers a range of issues within a given topic (132). This broader coverage comes at the expense of the more explicit methods, reporting and reproducibility, that are associated with systematic reviews, which tend to focus on narrower topics using prescribed search methods (132). Given the methodological limitations of the narrative method, and the acknowledged potential for selection biases in study selection when a nonsystematic review is undertaken, the reader should turn to determinant-specific systematic reviews for exhaustive discussion of the specific determinants covered in this review. The main objective of this review was to summarize key early determinants of childhood obesity within the important framework of individual-, family-, and community-level biological and social influences acting across early life.

Consideration of determinants of obesity within this broader multilevel framework may imply that strategies for health promotion and primary prevention should include attention to determinants at all levels. The upstream influences on childhood obesity occur at many levels, including the family and the community, and begin very early in the life course. Health promotion activities typically target individual lifestyle factors, despite emerging evidence of the importance of broader environmental prevention targets (133). Family-based interventions to improve the home food environment (90) and parenting style (134) and policies to reduce the costs of healthy food choices (135) are needed. Prevention efforts should also include programs to reduce financial stress in families and programs aimed at teaching children on how to cope with stressors in their environment (86). It has been suggested that overweight and obesity reductions may accrue if the prevention focus is shifted, more broadly, to promoting healthy lifestyles and healthy environments and beyond the focus on individual children’s body weight as the outcome (136). The opportunities for early health promotion require attention simultaneously to many levels (30), suggesting the need to address the individual, family, and physical environment, the social environment, and social policy.

Statement of Financial Support

None.

Disclosure

none; there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, et al. Child and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger picture. Lancet 2015;385:2510–20.

Rokholm B, Baker JL, Sørensen TI. The levelling off of the obesity epidemic since the year 1999–a review of evidence and perspectives. Obes Rev 2010;11:835–46.

Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. Future Child 2006;16:47–67.

Amed S, Dean HJ, Panagiotopoulos C, et al. Type 2 diabetes, medication-induced diabetes, and monogenic diabetes in Canadian children: a prospective national surveillance study. Diabetes Care 2010;33:786–91.

Clarson CL, Mahmud FH, Baker JE, et al. Metformin in combination with structured lifestyle intervention improved body mass index in obese adolescents, but did not improve insulin resistance. Endocrine 2009;36:141–6.

Thompson DR, Obarzanek E, Franko DL, et al. Childhood overweight and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. J Pediatr 2007;150:18–25.

Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:653–8.

Steinberger J, Moran A, Hong CP, Jacobs DR Jr, Sinaiko AR. Adiposity in childhood predicts obesity and insulin resistance in young adulthood. J Pediatr 2001;138:469–73.

Stelmach-Mardas M, Mardas M, Walkowiak J, Boeing H. Long-term weight status in regainers after weight loss by lifestyle intervention: status and challenges. Proc Nutr Soc 2014;73:509–18.

Wiegand S, Keller KM, Lob-Corzilius T, et al. Predicting weight loss and maintenance in overweight/obese pediatric patients. Horm Res Paediatr 2014;82:380–7.

Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: a bioecological model. Psychol Rev 1994;101:568–86.

Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev 2001;2:159–71.

Hanson MA, Gluckman PD. Early developmental conditioning of later health and disease: physiology or pathophysiology? Physiol Rev 2014;94:1027–76.

Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:285–93.

Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS. Obesogenic clusters: multidimensional adolescent obesity-related behaviors in the U.S. Ann Behav Med 2008;36:217–30.

Nelson MC, Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM. Adolescent physical activity and sedentary behavior: patterning and long-term maintenance. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:259–66.

Owen N, Leslie E, Salmon J, Fotheringham MJ. Environmental determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2000;28:153–8.

Speakman JR. Obesity: the integrated roles of environment and genetics. J Nutr 2004;134:Suppl 8:2090S–105S.

Bouchard C. Gene-environment interactions in the etiology of obesity: defining the fundamentals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:Suppl 3:S5–S10.

Kosti RI, Panagiotakos DB, Tountas Y, et al. Parental body mass index in association with the prevalence of overweight/obesity among adolescents in Greece; dietary and lifestyle habits in the context of the family environment: the Vyronas study. Appetite 2008;51:218–22.

Qi L, Cho YA. Gene-environment interaction and obesity. Nutr Rev 2008;66:684–94.

Crossman A, Anne Sullivan D, Benin M. The family environment and American adolescents’ risk of obesity as young adults. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:2255–67.

Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA. Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutr Rev 2008;66:123–40.

Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M. Personal, behavioral, and environmental risk and protective factors for adolescent overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2748–60.

Arcan C, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P, van den Berg P, Story M, Larson N. Parental eating behaviours, home food environment and adolescent intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy foods: longitudinal findings from Project EAT. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:1257–65.

Pinard CA, Yaroch AL, Hart MH, Serrano EL, McFerren MM, Estabrooks PA. Measures of the home environment related to childhood obesity: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:97–109.

Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Austin SB. Examination of shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:336–43.

Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prevention of obesity and eating disorders: a consideration of shared risk factors. Health Educ Res 2006;21:770–82.

Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:719–30.

Gluckman P, Nishtar S, Armstrong T. Ending childhood obesity: a multidimensional challenge. Lancet 2015;385:1048–50.

Jeffery RW, Utter J. The changing environment and population obesity in the United States. Obes Res 2003;11:Suppl:12S–22S.

Gilliland J . The built environment and obesity: trimming waistlines through neighbourhood design. In: Bunting E, Filion P, Walker R, eds. Canadian Cities in Transition. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2010:391–410.

Gilliland JA, Rangel CY, Healy MA, et al. Linking childhood obesity to the built environment: a multi-level analysis of home and school neighbourhood factors associated with body mass index. Can J Public Health 2012;103:Suppl 3:eS15–21.

Ford PB, Dzewaltowski DA. Disparities in obesity prevalence due to variation in the retail food environment: three testable hypotheses. Nutr Rev 2008;66:216–28.

Rahman T, Cushing RA, Jackson RJ. Contributions of built environment to childhood obesity. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:49–57.

Zhang X, van der Lans I, Dagevos H. Impacts of fast food and the food retail environment on overweight and obesity in China: a multilevel latent class cluster approach. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:88–96.

Epstein LH, Raja S, Daniel TO, et al. The built environment moderates effects of family-based childhood obesity treatment over 2 years. Ann Behav Med 2012;44:248–58.

He M, Tucker P, Gilliland J, Irwin JD, Larsen K, Hess P. The influence of local food environments on adolescents’ food purchasing behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:1458–71.

Lopez RP, Hynes HP. Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: public health research needs. Environ Health 2006;5:25.

Oreskovic NM, Winickoff JP, Kuhlthau KA, Romm D, Perrin JM. Obesity and the built environment among Massachusetts children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:904–12.

Tucker P, Irwin JD, Gilliland J, He M, Larsen K, Hess P. Environmental influences on physical activity levels in youth. Health Place 2009;15:357–63.

Larsen K, Gilliland J, Hess PM. Route-based analysis to capture the environmental influences on a child’s mode of travel between home and school. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 2012;102:1348–65.

Björk J, Albin M, Grahn P, et al. Recreational values of the natural environment in relation to neighbourhood satisfaction, physical activity, obesity and wellbeing. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:e2.

Penney TL, Almiron-Roig E, Shearer C, McIsaac JL, Kirk SF. Modifying the food environment for childhood obesity prevention: challenges and opportunities. Proc Nutr Soc 2014;73:226–36.

Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 1990;301:1111.

Zafon C. Oscillations in total body fat content through life: an evolutionary perspective. Obes Rev 2007;8:525–30.

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Beedle AS, Raubenheimer D. Fetal and neonatal pathways to obesity. Front Horm Res 2008;36:61–72.

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental and epigenetic pathways to obesity: an evolutionary-developmental perspective. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:Suppl 7:S62–71.

Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Tuomilehto J, Winter PD, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Catch-up growth in childhood and death from coronary heart disease: longitudinal study. BMJ 1999;318:427–31.

Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Early growth and coronary heart disease in later life: longitudinal study. BMJ 2001;322:949–53.

Soto N, Bazaes RA, Peña V, et al. Insulin sensitivity and secretion are related to catch-up growth in small-for-gestational-age infants at age 1 year: results from a prospective cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:3645–50.

Nobili V, Alisi A, Panera N, Agostoni C. Low birth weight and catch-up-growth associated with metabolic syndrome: a ten year systematic review. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2008;6:241–7.

Morgan AR, Thompson JM, Murphy R, et al. Obesity and diabetes genes are associated with being born small for gestational age: results from the Auckland Birthweight Collaborative study. BMC Med Genet 2010;11:125.

Elks CE, Loos RJ, Sharp SJ, et al. Genetic markers of adult obesity risk are associated with greater early infancy weight gain and growth. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000284.

Kramer MS. Invited commentary: association between restricted fetal growth and adult chronic disease: is it causal? Is it important? Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:605–8.

Tu YK, West R, Ellison GT, Gilthorpe MS. Why evidence for the fetal origins of adult disease might be a statistical artifact: the “reversal paradox” for the relation between birth weight and blood pressure in later life. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:27–32.

Kramer MS, Martin RM, Bogdanovich N, Vilchuk K, Dahhou M, Oken E. Is restricted fetal growth associated with later adiposity? Observational analysis of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:176–81.

Joseph KS. Should we intervene to improve fetal and infant growth? In: Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, eds. A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004:399–414.

Adair LS. Child and adolescent obesity: epidemiology and developmental perspectives. Physiol Behav 2008;94:8–16.

Huang JS, Lee TA, Lu MC. Prenatal programming of childhood overweight and obesity. Matern Child Health J 2007;11:461–73.

Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005;115:e290–6.

Murphy MJ, Metcalf BS, Jeffery AN, Voss LD, Wilkin TJ. Does lean rather than fat mass provide the link between birth weight, BMI, and metabolic risk? EarlyBird 23. Pediatr Diabetes 2006;7:211–4.

Singhal A, Wells J, Cole TJ, Fewtrell M, Lucas A. Programming of lean body mass: a link between birth weight, obesity, and cardiovascular disease? Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:726–30.

Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman S, Berkey CS, Field AE, Colditz GA. Maternal gestational diabetes, birth weight, and adolescent obesity. Pediatrics 2003;111:e221–6.

Kim SY, Sharma AJ, Sappenfield W, Wilson HG, Salihu HM. Association of maternal body mass index, excessive weight gain, and gestational diabetes mellitus with large-for-gestational-age births. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:737–44.

Sridhar SB, Ferrara A, Ehrlich SF, Brown SD, Hedderson MM. Risk of large-for-gestational-age newborns in women with gestational diabetes by race and ethnicity and body mass index categories. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1255–62.

Dabelea D, Crume T. Maternal environment and the transgenerational cycle of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes 2011;60:1849–55.

Ma RC, Tutino GE, Lillycrop KA, Hanson MA, Tam WH. Maternal diabetes, gestational diabetes and the role of epigenetics in their long term effects on offspring. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2015;118:55–68.

Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Camargo CA Jr, et al. Risk of overweight among adolescents who were breastfed as infants. JAMA 2001;285:2461–7.

Hediger ML, Overpeck MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Ruan WJ. Association between infant breastfeeding and overweight in young children. JAMA 2001;285:2453–60.

Hawkins SS, Cole TJ, Law C ; Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group. An ecological systems approach to examining risk factors for early childhood overweight: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:147–55.

Arenz S, Rückerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R. Breast-feeding and childhood obesity–a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:1247–56.

Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics 2005;115:1367–77.

Fisher JO, Birch LL, Smiciklas-Wright H, Picciano MF. Breast-feeding through the first year predicts maternal control in feeding and subsequent toddler energy intakes. J Am Diet Assoc 2000;100:641–6.

Kirchberg FF, Harder U, Weber M, et al.; European Childhood Obesity Trial Study Group. Dietary protein intake affects amino acid and acylcarnitine metabolism in infants aged 6 months. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:149–58.

Rossiter MD, Colapinto CK, Khan MK, et al. Breast, formula and combination feeding in relation to childhood obesity in Nova Scotia, Canada. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2048–56.

Mennella JA, Trabulsi JC. Complementary foods and flavor experiences: setting the foundation. Ann Nutr Metab 2012;60:Suppl 2:40–50.

Stettler N, Zemel BS, Kumanyika S, Stallings VA. Infant weight gain and childhood overweight status in a multicenter, cohort study. Pediatrics 2002;109:194–9.

Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, Kleijnen J, Roberts H, Law C. Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 2005;331:929.

Dubois L, Girard M. Early determinants of overweight at 4.5 years in a population-based longitudinal study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:610–7.

Çamurdan MO, Çamurdan AD, Polat S, Beyazova U. Growth patterns of large, small, and appropriate for gestational age infants: impacts of long-term breastfeeding: a retrospective cohort study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2011;24:463–8.

Lumeng JC, Wendorf K, Pesch MH, et al. Overweight adolescents and life events in childhood. Pediatrics 2013;132:e1506–12.

Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav 2005;46:205–19.

Wickrama KK, O’Neal CW, Oshri A. Are stressful developmental processes of youths leading to health problems amplified by genetic polymorphisms? The case of body mass index. J Youth Adolesc 2014;43:1096–109.

Magrone T, Jirillo E. Childhood obesity: immune response and nutritional approaches. Front Immunol 2015;6:76.

Gundersen C, Mahatmya D, Garasky S, Lohman B. Linking psychosocial stressors and childhood obesity. Obes Rev 2011;12:e54–63.

Huybrechts I, De Vriendt T, Breidenassel C, et al.; HELENA Study Group. Mechanisms of stress, energy homeostasis and insulin resistance in European adolescents–the HELENA study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:1082–9.

Pasquali R. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sex hormones in chronic stress and obesity: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. Ann NY Acad Sci 2012;1264:20–35.

Vanaelst B, Michels N, Clays E, et al. The association between childhood stress and body composition, and the role of stress-related lifestyle factors–cross-sectional findings from the baseline ChiBSD survey. Int J Behav Med 2014;21:292–301.

Renzaho AM, Dau A, Cyril S, Ayala GX. The influence of family functioning on the consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages among 1- to 12-y-old children in Victoria, Australia. Nutrition 2014;30:1028–33.

Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2014;19:544–54.

Shankardass K, McConnell R, Jerrett M, et al. Parental stress increases body mass index trajectory in pre-adolescents. Pediatr Obes 2014;9:435–42.

Bornstein SR, Schuppenies A, Wong ML, Licinio J. Approaching the shared biology of obesity and depression: the stress axis as the locus of gene-environment interactions. Mol Psychiatry 2006;11:892–902.

de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res 2010;178:230–5.

McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Malhotra S, Nelson EB, Keck PE, Nemeroff CB. Are mood disorders and obesity related? A review for the mental health professional. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:634–51, quiz 730.

Stunkard AJ, Faith MS, Allison KC. Depression and obesity. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:330–7.

Erickson SJ, Robinson TN, Haydel KF, Killen JD. Are overweight children unhappy?: Body mass index, depressive symptoms, and overweight concerns in elementary school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:931–5.

Needham BL, Crosnoe R. Overweight status and depressive symptoms during adolescence. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:48–55.

Ross CE. Overweight and depression. J Health Soc Behav 1994;35:63–79.

Duclos M, Gatta B, Corcuff JB, Rashedi M, Pehourcq F, Roger P. Fat distribution in obese women is associated with subtle alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and sensitivity to glucocorticoids. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:447–54.

Penninx BW, Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Vogelzangs N. Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Med 2013;11:129.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:220–9.

Surkan PJ, Kawachi I, Peterson KE. Childhood overweight and maternal depressive symptoms. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:e11.

Wang L, Anderson JL, Dalton Iii WT, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and the risk of overweight in their children. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:940–8.

Ramasubramanian L, Lane S, Rahman A. The association between maternal serious psychological distress and child obesity at 3 years: a cross-sectional analysis of the UK Millennium Cohort Data. Child Care Health Dev 2013;39:134–40.

Gross RS, Velazco NK, Briggs RD, Racine AD. Maternal depressive symptoms and child obesity in low-income urban families. Acad Pediatr 2013;13:356–63.

Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Modi AC, Gutzwiller J, Vannatta K, Davies WH. Controlled study of critical parent and family factors in the obesigenic environment. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:126–36.

Stout SA, Espel EV, Sandman CA, Glynn LM, Davis EP. Fetal programming of children’s obesity risk. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;53:29–39.

Hohwü L, Henriksen TB, Grønborg TK, Hedegaard M, Sørensen TI, Obel C. Maternal salivary cortisol levels during pregnancy are positively associated with overweight children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;52:143–52.

Farrow CV, Blissett JM. Is maternal psychopathology related to obesigenic feeding practices at 1 year? Obes Res 2005;13:1999–2005.

Wachs TD. Multiple influences on children’s nutritional deficiencies: a systems perspective. Physiol Behav 2008;94:48–60.

de Campora G, Giromini L, Larciprete G, Li Volsi V, Zavattini GC. The impact of maternal overweight and emotion regulation on early eating behaviors. Eat Behav 2014;15:403–9.

McConley RL, Mrug S, Gilliland MJ, et al. Mediators of maternal depression and family structure on child BMI: parenting quality and risk factors for child overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:345–52.

Milgrom J, Skouteris H, Worotniuk T, Henwood A, Bruce L. The association between ante- and postnatal depressive symptoms and obesity in both mother and child: a systematic review of the literature. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e319–28.

O’Dea JA, Chiang H, Peralta LR. Socioeconomic patterns of overweight, obesity but not thinness persist from childhood to adolescence in a 6-year longitudinal cohort of Australian schoolchildren from 2007 to 2012. BMC Public Health 2014;14:222.

Kakinami L, Séguin L, Lambert M, Gauvin L, Nikiema B, Paradis G. Poverty’s latent effect on adiposity during childhood: evidence from a Québec birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:239–45.

Lee H, Andrew M, Gebremariam A, Lumeng JC, Lee JM. Longitudinal associations between poverty and obesity from birth through adolescence. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e70–6.

McCurdy K, Gorman KS, Kisler T, Metallinos-Katsaras E. Associations between family food behaviors, maternal depression, and child weight among low-income children. Appetite 2014;79:97–105.

de Jong E, Visscher TL, HiraSing RA, Seidell JC, Renders CM. Home environmental determinants of children’s fruit and vegetable consumption across different SES backgrounds. Pediatr Obes 2015;10:134–40.

Carroll-Scott A, Gilstad-Hayden K, Rosenthal L, et al. Disentangling neighborhood contextual associations with child body mass index, diet, and physical activity: the role of built, socioeconomic, and social environments. Soc Sci Med 2013;95:106–14.

Lovasi GS, Schwartz-Soicher O, Quinn JW, et al. Neighborhood safety and green space as predictors of obesity among preschool children from low-income families in New York City. Prev Med 2013;57:189–93.

Malhotra K, Herman AN, Wright G, Bruton Y, Fisher JO, Whitaker RC. Perceived benefits and challenges for low-income mothers of having family meals with preschool-aged children: childhood memories matter. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:1484–93.

Hernandez DC, Pressler E. Accumulation of childhood poverty on young adult overweight or obese status: race/ethnicity and gender disparities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:478–84.

Miller GE, Chen E. The biological residue of childhood poverty. Child Dev Perspect 2013;7:67–73.

Wisniewski AB, Chernausek SD. Gender in childhood obesity: family environment, hormones, and genes. Gend Med 2009;6:Suppl 1:76–85.

Sweeting HN. Gendered dimensions of obesity in childhood and adolescence. Nutr J 2008;7:1.

Hernandez DC, Pressler E. Gender disparities among the association between cumulative family-level stress & adolescent weight status. Prev Med 2015;73:60–6.

Widén E, Silventoinen K, Sovio U, et al. Pubertal timing and growth influences cardiometabolic risk factors in adult males and females. Diabetes Care 2012;35:850–6.

Goran MI, Gower BA. Longitudinal study on pubertal insulin resistance. Diabetes 2001;50:2444–50.

Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychol Bull 2001;127:773–96.

Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol 1998;107:128–40.

Collins JA, Fauser BC. Balancing the strengths of systematic and narrative reviews. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:103–4.

Alvaro C, Jackson LA, Kirk S, et al. Moving Canadian governmental policies beyond a focus on individual lifestyle: some insights from complexity and critical theories. Health Promot Int 2011;26:91–9.

Kakinami L, Barnett TA, Séguin L, Paradis G. Parenting style and obesity risk in children. Prev Med 2015;75:18–22.

Morrissey TW, Jacknowitz A, Vinopal K. Local food prices and their associations with children’s weight and food security. Pediatrics 2014;133:422–30.

Penney TL, Kirk SF. The health at every size paradigm and obesity: missing empirical evidence may help push the reframing obesity debate forward. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e38–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, M. Biological, environmental, and social influences on childhood obesity. Pediatr Res 79, 205–211 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.208

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.208

This article is cited by

-

Bayesian spatial modeling of childhood overweight and obesity prevalence in Costa Rica

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Likelihood of obesity in early and late childhood based on growth trajectory during infancy

International Journal of Obesity (2023)

-

Rare genetic forms of obesity in childhood and adolescence, a comprehensive review of their molecular mechanisms and diagnostic approach

European Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

-

Neighborhood Walkability, Historical Redlining, and Childhood Obesity in Denver, Colorado

Journal of Urban Health (2023)

-

Mothers as advocates for healthier lifestyle behaviour environments for their children: results from INFANT 3.5-year follow-up

BMC Public Health (2022)