Abstract

Introduction:

To investigate whether immunologic factors in breast milk change in response to nursing infants’ infection.

Results:

Total CD45 leukocyte count dropped from 5,655 (median and interquartile range: 1,911; 16,871) in the acute phase to 2,122 (672; 6,819) cells/ml milk after recovery with macrophage count decreasing from 1,220 (236; 3,973) to 300 (122; 945) cells/ml. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) levels decreased from 3.66 ± 1.68 to 2.91 ± 1.51 pg/ml. The decrease in lactoferrin levels was of borderline statistical significance. Such differences were not recorded in samples of the controls. Interleukin-10 levels decreased in the sick infants’ breast milk after recovery, but also in the healthy controls, requiring further investigation. Secretory immunoglobulin A levels did not change significantly in the study or control group.

Discussion:

During active infection in nursing infants, the total number of white blood cells, specifically the number of macrophages, and TNFα levels increase in their mothers’ breast milk. These results may support the dynamic nature of the immune defense provided by breastfeeding sick infants.

Methods:

Breast milk from mothers of 31 infants, up to 3 months of age, who were hospitalized with fever, was sampled during active illness and recovery. Milk from mothers of 20 healthy infants served as controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The increased sensitivity of the newborn infant to infections originates from the immaturity of the immune system (1). In addition to transfer of immunoglobulin G to the fetus through the placenta, breastfeeding constitutes an important immunological support that the mammalian mother can provide to her relatively immunocompromised offspring against infections during the first months of life (2,3,4,5,6). The immune system in human milk includes secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA), immunoglobulin G, free fatty acids, monoglycerides, proteins such as lactoferrin, lactalbumin, glycans, nonabsorbed oligosaccharides, exosomes, immunomodulators such as cytokines, nucleic acids, antioxidants, and immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes (1,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17). All these immunologic milk constituents interact together and with the newborn’s gut directly or indirectly (e.g., by changing the gut flora) to increase immunity against infection, and probably also contribute to the maturation and efficiency of the newborn immune system (5,6).

Many studies in both industrialized and developing countries have shown that nursing infants are less vulnerable to infections during their first months of life, including gastroenteritis, respiratory infections, otitis media, urinary tract infections, and necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants (3,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25).

The mechanisms involved in the immunity provided by human milk to the nursing infant are not fully understood. Until recently, it was believed that the changes in immunological constituents of breast milk were mostly related to the time that elapsed from delivery or, in some cases, were also related to the mother’s nutritional state. It was unknown if such a passive and relatively constant immunological defense could have changed according to the active needs of the nursing infant in response to situations such as infections. The aim of this study was to investigate whether some of the immunologic factors in breast milk change in response to infections in nursing infants.

Results

The characteristics of the study and control groups are shown in Table 1 . Most of the characteristics were not statistically different, except for the fact that some of the mothers and sibs of infants in the study group were sick at the time of the first milk sampling, as would be expected for many infectious diseases, especially viral, in families with small children.

The infants of the study group comprised 12 infants with undefined viral disease (41.38%), 1 with gastroenteritis (3.45%), 5 with upper respiratory infection (17.24%), and 13 with proven focal localized infection: 5 with urinary tract infection (13.79%), 2 with pneumonia (6.90%), 1 with acute otitis media (3.45%), 4 with meningitis (10.34%), and 1 with periorbital cellulitis (3.45%). The average time that elapsed from symptoms in the babies to the first milk sampling from the mothers was 48.00 ± 26.83 h.

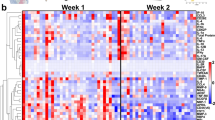

Table 2 compares the immunological characteristics of the first and second milk samples taken from the mothers of the study group (the left-hand columns designated P). From these data, it can be noted that the total number of CD45+ leukocytes significantly decreased between the times of active illness and convalescence. This decrease was more pronounced in the fraction of macrophages. The decrease in neutrophils and lymphocytes was only of borderline statistical significance. These differences in the counts of the leukocytes during the active infection and recovery phases were more pronounced between the two samples of milk taken from the 13 mothers of infants with proven focal infection (as defined above). In this subgroup, the total number of CD45+ leukocytes dropped from (mean (interquartile range) 9,512 (2,180; 36,909) to 2,337 (672; 5,014) cells/ml (P < 0.001), the number of macrophages decreased from 2,736 (276; 6,020) to 317 (122; 1,203) cells/ml (P < 0.001), the total number of lymphocytes decreased from 2,474 (330; 13,981) to 325 (177; 1,957) cells/ml (P = 0.034), and the neutrophils decreased from 2,941 (1,152; 16,739) to 813 (312; 2,297) cells/ml (P = 0.005).

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) levels in the breast milk of the mothers in the study group dropped significantly during the recovery phase of their infants ( Table 2 , columns designated P). TNFα levels were positively correlated to total CD45 leukocyte and macrophage counts (Spearman rank order correlation coefficients of 0.35 and 0.34, respectively, P < 0.005), as demonstrated in Figure 1 (panels a and b, respectively) after logarithmic transformation.

Pearson’s correlation between tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) levels and (a) the total number of CD45+ and (b) macrophage cells in human breast milk samples. (a) TNFα breast milk levels and the number of CD45+ cells were calculated for each sample. After logarithmic transformation, correlation between the two variables was plotted and calculated (R = 0.46, P < 0.001). (b) The levels of TNFα and the number of macrophages were calculated for each breast milk sample. After logarithmic transformation, correlation between the two variables was calculated and plotted (R = 0.50, P < 0.001).

Although the decrease we found in interleukin-10 (IL-10) levels was also statistically significant, this result should be interpreted cautiously, as a similar finding was recorded in the control group as well ( Table 2 , columns P vs. C). The reduction in lactoferrin levels between the first and second samples of the study group was of borderline statistical significance. In contrast, no significant difference was found in sIgA levels ( Table 2 , columns P).

No significant differences were recorded between the first and second milk samples collected from the mothers of the control group in breast milk CD45+ cells or in the levels of TNFα, lactoferrin, or sIgA ( Table 2 , columns C). However, IL-10 levels dropped significantly, as mentioned above.

As a significant portion (35%) of the mothers of the sick infants reported being sick as well, although not verified by physical examination or laboratory tests, we conducted additional analysis to check whether this might have affected the concentrations of leukocytes in their breast milk. Thus, we analyzed the differences in milk constituents without this group of mothers who reported being sick. This additional analysis, presented in columns N of Table 2 , still showed that in the nonsick mothers’ milk, the total number of CD45+ leukocytes significantly decreased between the times of active illness and convalescence of their infants and that this decrease was more pronounced in the fraction of macrophages. Although the same trends of decrease were noted for TNFα, lactoferrin, and IL-10 levels after recovery, these changes did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to the smaller sample size (n = 20).

We also compared the study and control groups ( Table 3 ). In line with our previous analysis where each mother served as her own control as we examined changes between the first and second samples of milk, the comparison between the study and control groups was based on analysis of the differences in the proportions of changes seen within each group. Such comparison seems to be the most appropriate in face of the wide biologic variation in the constituents of milks taken from different mothers. These comparisons, presented in Table 3 , further demonstrate the decrease in the total number of CD45+ leukocytes in the milk of the mothers between the times of active illness and convalescence of their infants and that this decrease was most pronounced in the fraction of macrophages.

Discussion

Human breast milk provides a significant immunologic support system for the infant during the first months of life. In our study, we found that the mean number of white blood cells (CD45+) in mothers’ milk significantly declined between the active infection and convalescence phases of their nursing infants, the most significant and pronounced drop being in the number of macrophages. The number of lymphocytes and neutrophils also decreased. This decline was more significant in the milk of the mothers of the infants with proven localized infection. No similar changes were demonstrated in the control group.

The levels of TNFα significantly decreased in the milk of the mothers of the study group between the times of acute infection and recovery. The levels of lactoferrin also showed a tendency to decrease, but this was only of borderline statistical significance. Although IL-10 levels dropped significantly, this finding should be interpreted cautiously because a similar drop was also noted in the control group.

There is a wide variability in the composition of breast milk between lactating women, in the amount of the different nutrients as well as in the cellular components, oligosaccharides, and cytokine levels. This variability, which may be diurnal and even occur within the same breastfeeding, is also controlled genetically and may depend on the atopic status of the mother (26,27,28,29). To deal with this significant biologic variability, we took two samples from each nursing mother in the study and control groups so that each mother became her own control. The first sample taken from the study mothers reflected milk composition during active infection and the second sample reflected the changes in its composition during convalescence. The lack of similar changes between the two samples of milk in the control group formed a sound basis for defining the changes between milk samples in the study group as true evidence for immunological change in mother’s milk composition in response to infection.

It is known that maternal blood leukocytes that home to the mammary gland pass through the junctures of epithelial cells and are secreted into the breast milk. In contrast, blood monocytes reaching the mammary gland are activated locally to become macrophages and are then secreted into the breast milk.

Our main finding is the increase in the total number of white blood cells in mothers’ milk in relation to active infection in their nursing infants. The mechanism explaining this phenomenon is not clear and has not been investigated in this study. It is reasonable to assume that respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infections in the infant actually infect the mother as well, resulting in inflammatory response in her body that causes increased secretion of white blood cells and cytokines into the milk she produces. One can speculate that the inflammatory response might increase her blood leukocytes or attract more cells to the mammary gland or alternate the intra-mammary cell traffic, resulting in increase of secreted cells in the breast milk. Support to this hypothesis in our data is the finding that 35% of the mothers and 65% of the sibs of the study infants had concurrent fever. This mechanism looks less plausible in cases of bacterial or localized infections like urinary tract infections or meningitis. However, when we specifically investigated the breast milk cell components of only the nonsick mothers, we still found that during infant infection vs. recovery, they secreted statistically significant increased numbers of leukocytes and macrophages.

We have also demonstrated in our study that TNFα concentrations in breast milk of the study group mothers were relatively high in the first samples during infection and then significantly declined during convalescence of their infants. The main source of TNFα is from secretion of macrophages, although other cells like neutrophils, T and B lymphocytes, and natural killer cells can also secrete TNFα, especially after antigenic stimulation of bacterial origin. The finding of increased inflammatory cells, especially macrophages and neutrophils, in human milk taken from the mothers of the sick infants can explain the increased levels of TNFα. This explanation is supported by the positive correlation we have found between the total number of CD45+ leukocytes, especially the number of macrophages, and the levels of TNFα ( Figure 1 ).

Lactoferrin is secreted by the epithelial cells of the mammary tissue and by activated leukocytes. In our study, we have demonstrated higher levels of lactoferrin in the milk of mothers nursing sick infants. Although this difference did not reach the required level of statistical significance, it showed borderline significant tendency that was not observed in the control group. This might be explained by the fact that the increase we found in the number of activated neutrophils, which secrete some of the lactoferrin in breast milk during infection, was also at the level of borderline significance.

sIgA is secreted from mammary lymphoid cells that probably originate from B lymphocytes migrating from the gastrointestinal tract to the mammary gland (4). Only a small portion of sIgA is secreted from macrophages containing this antibody. From our results, it seems that the secretion of this immunoglobulin antibody is not affected enough by infectious disease in the nursing infant to cause a statistically significant elevation.

The immunological meaning of our finding is not clear. One can speculate that the increased number of cells as well as the higher levels of TNFα and, to a lesser extent, lactoferrin in human milk can help the nursing child cope with infection. This is supported by the proven ability of macrophages and leukocytes from human milk to kill enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Giardia lamblia, Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida albicans (30,31,32).

Although this suggested dynamic interaction between the sick babies and their mothers that alters the milk to help protect the babies seems very plausible, it is possible that some of the findings in the first milk samples from the mothers of the sick infants (e.g., more CD45 cells and higher TNFα levels, especially in comparison with those found in the controls, Table 2 ) actually reflect a nonspecific stress response of the mothers whose infants were hospitalized.

In summary, in this study we have found that during active infection in the nursing infant, the total number of white blood cells, specifically the number of macrophages, and TNFα levels increase. Our findings support the dynamic immunological connection between lactating mothers and their nursing infants, especially during active infection, thus further encouraging breastfeeding. Our study provides only a glimpse into the rich nature of the immunological defense provided by human milk. Further studies are needed in order to enlighten the immunological mechanisms underlying these responses, as well as their clinical significance.

Methods

Subjects and Study Design

During the study period (1 March 2009 to 28 February 2010), milk samples were collected from 31 lactating mothers of infants aged 3 months or younger, who were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics in Bnai Zion Medical Center, for sepsis evaluation because of fever with or without other symptoms. Concurrently, milk samples were collected from 20 mothers of healthy nursing infants aged 3 months or younger, who served as controls.

This study was approved by the Bnai Zion Medical Center Ethical Committee and written informed consent was obtained from the mothers during recruitment to the study. The participating mothers from both the study and control groups were asked to provide two samples of breast milk ~7 days apart. The first sample of milk from mothers of the study group was collected during the hospitalization of their sick infants and the second was collected during recovery.

All the infants in this study were either exclusively breastfed or predominantly breastfed, i.e., more than 80% of their nutrition was based on breastfeeding. This was also true for the sick infants who were hospitalized, as in our pediatric ward we provide room for the mothers to be at their infants’ bedside at all times and fully nurse them. None of these sick infants was placed on intravenous fluids, parenteral nutrition, or any artificial alternative enteral formula, as our policy is to encourage continuous breastfeeding even while sick in the hospital. Thus, possible significant decrease in the production of milk that could have affected milk constituents, as occurs in partial weaning (33), was less likely.

Samples of milk (20–30 ml) were collected from each mother in the morning hours, just before breastfeeding, and were immediately transferred to the laboratory in sterile plastic containers at room temperature, so that they could be processed within 1 h of collection.

Analysis of Breast Milk Constituents

Whole-milk aliquots were centrifuged at 1,200g for 15 min, after which the lipid layer and aqueous fraction were removed. Aliquots of the aqueous fraction were stored at −70 °C until assayed for cytokines. The breast milk cell pellets were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline.

Flow Cytometry of Breast Milk Cells

For determination of leukocyte cell subsets, breast milk cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min with saturating concentrations of fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies and analyzed using a Beckman-Coulter (Brea, CA) FACScan Flow Cytometer. A three-color flow cytometry was performed. The cells were labeled with directly conjugated mouse monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibody to CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) phycoerythrin-Cy 5 and directly conjugated mouse monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibody to CD14/CD86, CD16/CD66b, or a combination of CD19 and CD3/CD56 (phycoerythrin or fluorescent isothiocyanate; Becton Dickinson). The neutrophils were characterized by labeling the cells with fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies against CD45/CD16/CD66b. CD66b reacts with human granulocytes and does not react with macrophages. To identify the macrophages group, we used a combination of fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies against CD45/CD14/CD86. The monoclonal antibodies that identify CD86 are expressed on macrophages and not on neutrophils. Each sample was live-gated using CD45 fluorescence and side-scatter parameters to collect 10,000 CD45+ events. Aliquots from 2 ml of breast milk were analyzed by FACScan in order to determine the total CD45 cell (breast milk immune cell) count per milliliter.

Analysis of Cytokine Concentrations in Breast Milk

The concentrations of TNFα and IL-10 in the aqueous fraction of the breast milk were determined using commercial high sensitivity sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (DuoSet R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Assays were performed as recommended by the manufacturer. The range of detected values for TNFα was 0.5–16 pg/ml and for IL-10 from 7.8–500 pg/ml.

Analysis of Lactoferrin Concentrations in Breast Milk

Lactoferrin concentrations were analyzed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay procedure (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). The minimum detectable dose level for lactoferrin was 1.56 ng/ml.

Analysis of sIgA Concentrations in Breast Milk

sIgA levels in human milk were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay procedure according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Bethyl Laboratories, Cat. No. E88-102). The minimum detectable dose level for sIgA was 1.03 ng/ml. The antibodies in this kit bind epitopes on the IgAα chain. As sIgA comprises ~90% of total IgA in human milk, most of the measured IgA was sIgA.

Data Analyses

Each lactating mother served as her own control as differences between the milk constituents in the two milk samples collected from her were compared. Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics, paired and unpaired Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the appropriate nonparametric tests when the normality test failed. Chi-square was used to assess differences with respect to dichotomous outcomes (SigmaStat version 2.03, Chicago, IL). Statistical difference was set at the 5% level of probability. Unless indicated otherwise, the data were expressed as mean ± s.d. values. When nonparametric tests were applied for data that were not normally distributed, these data were presented as median and interquartile (25%; 75%) range.

Statement of Financial Support

This study was supported by a research grant from Materna Research Institute, Maabarot, Israel.

References

Chirico G, Marzollo R, Cortinovis S, Fonte C, Gasparoni A . Antiinfective properties of human milk. J Nutr 2008;138:1801S–6.

Goldman AS, Chheda S, Garofalo R . Evolution of immunologic functions of the mammary gland and the postnatal development of immunity. Pediatr Res 1998;43:155–62.

Goldman AS . The immune system in human milk and the developing infant. Breastfeed Med 2007;2:195–204.

Hanson LA . Session 1: Feeding and infant development breast-feeding and immune function. Proc Nutr Soc 2007;66:384–96.

Newburg DS . Innate immunity and human milk. J Nutr 2005;135:1308–12.

Newburg DS, Walker WA . Protection of the neonate by the innate immune system of developing gut and of human milk. Pediatr Res 2007;61:2–8.

Bollinger RR, Everett ML, Palestrant D, et al. Human secretory immunoglobulin A may contribute to biofilm formation in the gut. Immunology 2003;109:580–7.

de la Rosa G, Yang D, Tewary P, Varadhachary A, Oppenheim JJ . Lactoferrin acts as an alarmin to promote the recruitment and activation of APCs and antigen-specific immune responses. J Immunol 2008;180:6868–76.

Field CJ . The immunological components of human milk and their effect on immune development in infants. J Nutr 2005;135:1–4.

Goldman AS, Chheda S, Garofalo R, Schmalstieg FC . Cytokines in human milk: properties and potential effects upon the mammary gland and the neonate. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 1996;1:251–8.

Gustafsson L, Hallgren O, Mossberg AK, et al. HAMLET kills tumor cells by apoptosis: structure, cellular mechanisms, and therapy. J Nutr 2005;135:1299–1303.

Hawkes JS, Bryan DL, James MJ, Gibson RA . Cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1, and TGF-beta2) and prostaglandin E2 in human milk during the first three months postpartum. Pediatr Res 1999;46:194–9.

Hawkes JS, Bryan DL, Gibson RA . Cytokine production by human milk cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the same mothers. J Clin Immunol 2002;22:338–44.

Morrow AL, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Jiang X, Newburg DS . Human-milk glycans that inhibit pathogen binding protect breast-feeding infants against infectious diarrhea. J Nutr 2005;135:1304–7.

Thormar H, Isaacs CE, Brown HR, Barshatzky MR, Pessolano T . Inactivation of enveloped viruses and killing of cells by fatty acids and monoglycerides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1987;31:27–31.

Ustundag B, Yilmaz E, Dogan Y, et al. Levels of cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-alpha) and trace elements (Zn, Cu) in breast milk from mothers of preterm and term infants. Mediators Inflamm 2005;2005:331–6.

Admyre C, Johansson SM, Qazi KR, et al. Exosomes with immune modulatory features are present in human breast milk. J Immunol 2007;179:1969–78.

Bryan DL, Hart PH, Forsyth KD, Gibson RA . Immunomodulatory constituents of human milk change in response to infant bronchiolitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2007;18:495–502.

Cushing AH, Samet JM, Lambert WE, et al. Breastfeeding reduces risk of respiratory illness in infants. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:863–70.

Duncan B, Ey J, Holberg CJ, et al. Exclusive breast-feeding for at least 4 months protects against otitis media. Pediatrics 1993;91:867–72.

Levy I, Comarsca J, Davidovits M, et al. Urinary tract infection in preterm infants: the protective role of breastfeeding. Pediatr Nephrol 2009;24:527–31.

Mårild S, Hansson S, Jodal U, Odén A, Svedberg K . Protective effect of breastfeeding against urinary tract infection. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:164–8.

Morrow AL, Reves RR, West MS, et al. Protection against infection with Giardia lamblia by breast-feeding in a cohort of Mexican infants. J Pediatr 1992;121:363–70.

Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A . Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e837–42.

Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, et al. An exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk-based products. J Pediatr 2010;156:562–7.e1.

Oddy WH, Halonen M, Martinez FD, et al. TGF-beta in human milk is associated with wheeze in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:723–8.

Pittard WB 3rd, Geddes KM, Pepkowitz SH, Carr R . The immunologic composition of neonatal milk: cellular components. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1988;46:294–8.

Rudloff S, Niehues T, Rutsch M, Kunz C, Schroten H . Inflammation markers and cytokines in breast milk of atopic and nonatopic women. Allergy 1999;54:206–11.

Erney RM, Malone WT, Skelding MB, et al. Variability of human milk neutral oligosaccharides in a diverse population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;30:181–92.

França-Botelho AC, Honório-França AC, França EL, Gomes MA, Costa-Cruz JM . Phagocytosis of Giardia lamblia trophozoites by human colostral leukocytes. Acta Paediatr 2006;95:438–43.

Honorio-França AC, Carvalho MP, Isaac L, Trabulsi LR, Carneiro-Sampaio MM . Colostral mononuclear phagocytes are able to kill enteropathogenic Escherichia coli opsonized with colostral IgA. Scand J Immunol 1997;46:59–66.

Robinson JE, Harvey BA, Soothill JF . Phagocytosis and killing of bacteria and yeast by human milk cells after opsonisation in aqueous phase of milk. Br Med J 1978;1:1443–5.

Goldman AS, Goldblum RM, Garza C, Nichols BL, Smith EO . Immunologic components in human milk during weaning. Acta Paediatr Scand 1983;72:133–4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riskin, A., Almog, M., Peri, R. et al. Changes in immunomodulatory constituents of human milk in response to active infection in the nursing infant. Pediatr Res 71, 220–225 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2011.34

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2011.34

This article is cited by

-

Breastfeeding support among re-hospitalized young children: a survey from Italy

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2024)

-

Dynamic change, influencing factors, and clinical impact of cellular components in human breast milk

Pediatric Research (2023)

-

COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-mediated antibodies in human breast milk and their association with breast milk microbiota composition

npj Vaccines (2023)

-

Racial and socioeconomic disparities in breast milk feedings in US neonatal intensive care units

Pediatric Research (2021)

-

Resolving Human Lactation Heterogeneity Using Single Milk-Derived Cells, a Resource at the Ready

Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia (2021)