Abstract

Bartter syndrome is an autosomic recessive disease characterized by severe polyuria and sodium renal loss. The responsible genes encode proteins involved in electrolyte tubular reabsorption. Prenatal manifestations, mainly recurrent polyhydramnios because of fetal polyuria, lead to premature delivery. After birth, polyuria leads to life-threatening dehydration. Prenatal genetic diagnosis needs an index case. The aim of this study was to analyze amniotic fluid biochemistry for the prediction of Bartter syndrome. We retrospectively studied 16 amniotic fluids of Bartter syndrome-affected fetuses diagnosed after birth, only six of them being genetically proven. We assayed total proteins, alpha-fetoprotein, and electrolytes and defined a Bartter index corresponding to the multiplication of total protein and of alpha-fetoprotein. Results were compared with two control groups matched for gestational age—non-Bartter polyhydramnios (n = 30) and nonpolyhydramnios (n = 60). In Bartter syndrome, we observed significant differences (p < 0.0001) for protein amniotic fluid levels when compared with the two control groups (1.55 g/L, 3.9 g/L, and 5.2 g/L, respectively) and low Bartter index (0.16, 0.82, and 1.0, respectively). No statistical difference was observed for electrolytes. In conclusion, Bartter syndrome can be prenatally suspected on amniotic fluid biochemistry (sensitivity 93% and specificity 100%), allowing appropriate management before and after birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Bartter syndrome in infancy and childhood results from a group of autosomal recessive disorders characterized by polyuria and renal sodium chloride loss and, as a consequence, secondary hyperaldosteronism with hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, and with normal or low blood pressure (1–3). Two distinct clinical presentations are described: antenatal form and “classical” form. Antenatal presentation associates polyhydramnios, premature birth, postnatal polyuria complicated by severe dehydration episodes, recurrent vomiting, failure to thrive, growth retardation, and hypercalciuria with nephrocalcinosis (3). In a few cases, antenatal Bartter syndrome is associated with deafness (4,5). Classical form presents a milder phenotype, and diagnosis is frequently delayed from infancy to adolescence (2).

Bartter syndrome is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding for four proteins involved in NaCl transport in the thick ascending limb of Henle's loop and in the distal convoluted tubule (6–10). Antenatal Bartter syndrome is frequently caused by mutations in the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter encoded by the SLC12A1 [solute carrier family 12 (sodium/potassium/chloride transporters, member 1, or NKCC2)] gene or in the potassium channel Kir 1.1 (or ROMK) encoded by the KCNJ1 (potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 1, alias Kir1.1, or ROMK1) gene. Bartter syndrome with deafness is caused by mutations in the subunit of ClC-Kb and ClC-Ka channels (barttin) encoded by BSND (Bartter syndrome with sensorineural deafness, alias BART) gene (11). Classical forms (12) are caused by mutations in the chloride channel ClC-Kb encoded by the CLCNKB (chloride channel Kb, alias hClC-K) gene.

The genetic diagnosis of Bartter syndrome is generally performed following a clinical diagnosis in a newborn. For a first pregnancy with polyhydramnios, or when mutations are unknown in the index case, the prenatal genetic diagnosis is not possible, and amniotic fluid biochemistry analysis would be helpful. However, published data are case reports, with discordant results. In this article, based on a series of 16 cases, we analyzed the value of amniotic fluid biochemistry for the prediction of Bartter syndrome.

METHODS

During the period 1991–2007, 1032 amniotic fluid samples were sent from different institutions to our laboratory for biochemical analysis to investigate polyhydramnios etiology. Amniotic fluid was kept frozen −20°C and retrospectively assayed. Polyhydramnios was diagnosed at routine ultrasound scan and was defined by an amniotic fluid index >24 cm (13). In accordance to French law, consent for amniocentesis and for laboratory testing was obtained from each patient since 1996. All patients underwent i) level 3 ultrasound evaluation, ii) fetal karyotyping, and iii) amniotic fluid biochemical analysis. When amniodrainage and/or nonsteroid antiinflammatory treatment were required, only samples before procedure was taken into account. Gestational age (wk and d) was determined by first-trimester ultrasound examination. Sixteen cases were clinically diagnosed as Bartter syndrome on postnatal findings (major polyuria with normal blood pressure, sodium chloride loss with secondary hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, and hyperreninemic hyperaldosteronism) and constituted the database of our study. This group (Bartter) was divided in two subgroups based on the identification of Bartter mutation (six cases) or unknown mutation (10 cases). Two control groups, both matched for gestational age were defined, an idiopathic polyhydramnios control group (n = 30) and a nonpolyhydramnios control group (n = 60) sampled for fetal karyotyping because of maternal age or Down syndrome risk >1/250 at maternal serum markers screening. Twin pregnancies, fetal aneuploidy, oligohydramnios, fetal morphologic abnormalities, and cases with a clear etiology of polyhydramnios (duodenal atresia) were excluded.

Mutation screening consisted of direct sequencing of the SLC12A1, KCNJ1, and CLCNKB genes as described elsewhere (9,11). In the group without mutation, no genetic screening was performed for patient 7 (parental refusal).

Biochemical analyses were assayed on amniotic fluid: total proteins (urinary/cerebrospinal fluid protein; Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) alpha-fetoprotein (AFP; DualKit; PerkinElmer, Turku, Finland) and sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, and phosphorus (ADVIA; Siemens, Tarrytown, United Kingdom). A Bartter index was defined corresponding to the multiplication of total protein and of AFP, both expressed in multiple of median (MoM). MoMs values correspond to the ratio between the observed raw value and the median raw value defined for the same gestational age. Median raw values for each gestational age have been previously defined on a large cohort of amniotic fluid samples and are routinely used for biochemical prenatal diagnosis.

Amniotic fluid aldosterone and renin-angiotensin were not assayed for this study, because a specific technical adjustment is necessary for amniotic fluid samples. ANOVA test was used for group comparisons, and p < 0.01 was considered as significant. The study was exempt from institutional review board approval because, at the time of prenatal diagnosis, amniotic fluid sampling was part of the routine diagnostic workup.

RESULTS

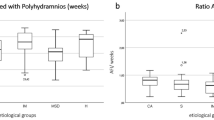

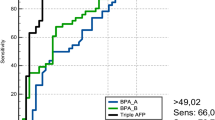

Bartter groups are presented in Table 1. Median gestational age at amniocentesis was 28.3 wk in the group with identified mutations and 26 wk in the group without identified mutation. All 16 infants presented neonatal manifestations of Bartter syndrome, with no difference in clinic or biologic signs. Table 2 presents the results of amniotic fluid biochemistry in the four groups defined as 1) Bartter with identified mutation; 2) Bartter without identified mutation; 3) control cases non-Bartter polyhydramnios, and 4) control cases nonpolyhydramnios. No statistical difference was observed for all makers between the two Bartter syndrome groups (with and without identified mutation), as between the two control groups (with and without polyhydramnios). No significant difference was noted for electrolytes between the two Bartter groups and between Bartter groups and control groups. A statistically significant difference (p < 0.0001) was observed for total protein and AFP between Bartter groups versus each of the two control groups, as well as for the Bartter index that we defined. Figure 1 displays the results of this Bartter index in the four groups. The best sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were observed for Bartter index (Table 3), using a cutoff at 0.25.

Amniotic fluid Bartter index = (protein MoM) × (AFP MoM) × 1000, in the four groups: group 1, Bartter infants with identified mutation; group 2, Bartter infants without identified mutation; group 3, polyhydramnios; and group 4, control group nonpolyhydramnios. AFP MoM, MoM of AFP. The solid dots correspond to the different individual values situated out of boxes representing mean and SD.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that Bartter syndrome can be prenatally diagnosed with simple amniotic fluid biochemical markers, even in the absence of family history. Mutations in genes encoding for four proteins involved in renal tubular NaCl transport are responsible of impaired sodium-chloride reabsorption and, as a consequence salt wasting, impaired urine concentration ability, and polyuria (leading to hydramnios during fetal life; 6–12). In this series of 16 Bartter syndrome patients with antenatal manifestations, all presented with postnatal clinical criteria of this syndrome (none of them presenting with deafness). However, genetic diagnosis was confirmed only in six. In the group of 10 patients without identified mutations, a complete screening of the implicated genes, including heterozygous deletions in CLCNKB gene, was performed. Mutations in the regulatory regions, intronic variants, or heterozygous deletions in SLC12A or KCNJ1 genes or unidentified genes cannot be ruled out.

Etiology of severe polyhydramnios (13) remains difficult to precise when no fetal malformation is detected at ultrasound scan (14). Prenatal diagnosis could be of interest for pregnancy management and delivery in the best conditions. In the absence of familial index cases with identified mutation, genetic prenatal diagnosis of Bartter syndrome is impossible because of the delay that occurs for sequencing of the four genes, and amniotic fluid biochemical analysis would be helpful. The main result brought about by our series is that total protein and AFP were significantly lower (p < 0.0001) than in control groups matched for gestational age. The best sensitivity and specificity for Bartter syndrome prenatal diagnosis (93.3 and 100%, respectively) was observed for the Bartter index we defined (multiplication of total protein and AFP MoMs).

Salt loss during fetal life was noted in Bartter syndrome by Sieck and Ohlsson (15), who observed a temporary increased level of electrolytes in the amniotic fluid collected near the fetal bladder just after voiding. Because fetal urine cannot be sampled for ethical and technical reasons, the abnormal urinary osmolarity cannot be demonstrated in clinical routine. Controversial results of amniotic fluid electrolytes have been reported in Bartter syndrome, especially abnormally high chloride values in case reports (16–18). By contrast, our series did not show any significant difference in electrolytes (sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium, and phosphorus) between Bartter groups and control groups. The normal values we observed are probably because of the continuous balance between amniotic fluid and maternal interstitial compartment, demonstrated by the constant isosmolality of amniotic fluid throughout pregnancy, whereas fetal urine, the major source of amniotic fluid, is hyposmotic in as soon as 20 wk (19). Polyhydramnios and high amniotic fluid chloride levels have also been described in chloride diarrhea; however, major digestive tract dilatations are always present at prenatal ultrasound scan (20).

In Bartter syndrome, the defect of sodium reabsorption interferes with the formation of a hypotonic tubular fluid at the end of Henle's loop and with the establishment of a hypertonic medullar interstitium gradient necessary for water reabsorption in the collecting duct. These abnormalities are responsible of a significant polyuria as demonstrated by Nakanishi et al. (21), who observed an abnormally high fetal urine production of 41 mL/h instead of 4–12 mL/h, and by Matsushita et al. (22), who observed a 72-mL/h production. Although renal protein filtration is unlikely to be affected in Bartter syndrome, the decrease of protein concentration might represent amniotic fluid protein dilution. This dilution is not observed in polyhydramnios of nonrenal origin, such as maternal diabetes, esophageal atresia, Pierre Robin syndrome, chloride diarrhea, or digestive tract atresia.

In conclusion, Bartter syndrome prenatal diagnosis is challenging because of the major polyhydramnios leading to premature birth and the risk of severe newborn dehydration, requiring management in intensive care unit. The amniotic fluid Bartter index that we proposed can be helpful to confirm prenatal diagnosis of Bartter syndrome. An early diagnosis will optimize the pregnancy follow-up and the management of the newborn.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

alpha-fetoprotein

- MoM:

-

multiple of median

References

Bartter FC, Pronove P, Gill JR, MacCardle RC 1962 Hyperplasia of the juxtaglomerular complex with hyperaldosteronism and hypokalemic alkalosis. A new syndrome. Am J Med 33: 811–828

Rodriguez-Soriano J 1998 Bartter and related syndromes: the puzzle is almost solved. Pediatr Nephrol 12: 315–327

Proesmans W 1997 Bartter syndrome and its neonatal variant. Eur J Pediatr 156: 669–679

Landau D, Shalev H, Ohaly M, Carmi R 1995 Infantile variant of Bartter syndrome and sensorineural deafness: a new autosomal recessive disorder. Am J Med Genet 59: 454–459

Jeck N, Reinalter SC, Henne T, Marg W, Mallmann R, Pasel K, Vollmer M, Klaus G, Leonhardt A, Seyberth HW, Konrad M 2001 Hypokalemic salt-losing tubulopathy with chronic renal failure and sensorineural deafness. Pediatrics 108: E5

Simon DB, Karet FE, Hamdan JM, DiPietro A, Sanjad SA, Lifton RP 1996 Bartter's syndrome, hypokalemic alkalosis with hypercalciuria, is caused by mutations in the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC2. Nat Genet 13: 183–188

Simon DB, Bindra RS, Mansfield TA, Nelson-Williams C, Mendonca E, Stone R, Schurman S, Navir A, Alpay H, Bakkaloglou A, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Morales JM, Sanjad SA, Taylor CM, Pliz D, Brem A, Trachtman H, Griswold W, Richard A, John E, Lifton RP 1997 Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, cause Bartter's syndrome type III. Nat Genet 17: 171–178

Birkenhager R, Otto E, Schurmann MJ, Vollmer M, Ruf EM, Maier-Lutz I, Beekmann F, Fekete A, Omran H, Feldmann D, Milford DV, Jeck N, Konrad M, Landau D, Knoers NV, Antignac C, Sudbrak R, Kispert A, Hildebrandt F 2001 Mutation of BSND causes Bartter syndrome with sensorineural deafness and kidney failure. Nat Genet 29: 310–314

Vargas-Poussou R, Feldmann D, Vollmer M, Konrad M, Kenny L, van den Heuvel LP, Tebourbi L, Brandis M, Karolyi L, Hebert S, Lemmik H, Deschenes G, Hildebrandt F, Seybertth HW, Guay-Woodfrod LM, Knoers NV, Antignac C 1998 Novel molecular variants of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter gene are responsible for antenatal Bartter syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 62: 1332–1340

Derst C, Konrad M, Köckerling A, Karolyi L, Deschenes G, Daut J, Karshin A, Seybertth HW 1997 Mutations in the gene ROMKA in antenatal Bartter syndrome are associated with impaired K+ channel function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 230: 641–645

Brochard K, Boyer O, Blanchard A, Loirat C, Niaudet P, Macher MA, Deschenes G, Bensman A, Decramer S, Cochat P, Morin D, Broux F, Caillez M, Guyot C, Novo R, Jeunemaitre X, Vargas-Poussou R 2009 Phenotype-genotype correlation in antenatal and neonatal variants of Bartter syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1455–1464

Konrad M, Vollmer M, Lemmink HH, van den Heuvel LP, Jeck M, Vargas-Poussou R, Lakings A, Ruf A, Deschenes G, Antignac C, Guay-Woodfrod LM, Knoers NV, Seybertth HW, Feldmann D, Hildebrandt F 2000 Mutations in the chloride channel gene CLCNKB as a cause of classic Bartter syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1449–1459

Alley MH, Hadjiev A, Mazneikova V, Dimitrov A 1998 Four-quadrant assessment of gestational age-specific values of amniotic fluid volume in uncomplicated pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 77: 290–294

Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Doherty DA, Lutgendorf MA, Magann MI, Morrison JC 2007 A review of idiopathic hydramnios and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv 62: 795–802

Sieck UV, Ohlsson A 1984 Fetal polyuria and hydramnios associated with Bartter's syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 63: 22S–24S

Proesmans W, Massa G, Vandenberghe K, Van Assche 1987 A prenatal diagnosis of Bartter syndrome. Lancet 1: 394

Dane B, Yayla M, Dane C, Cetin A 2007 Prenatal diagnosis of Bartter syndrome with biochemical examination of amniotic fluid: case report. Fetal Diagn Ther 22: 206–208

Shalev H, Ohaly M, Meizner I, Carmi R 1994 Prenatal diagnosis of Bartter syndrome. Prenat Diagn 14: 996–998

Muller F, Dommergues M, Bussieres L, Aegerter P, Le Fiblec B, Uzan S, Oury JF, Colau JC, Dumez Y 1996 Development of human renal function: reference intervals for 10 biochemical markers in fetal urine. Clin Chem 42: 1855–1860

Tsukimori K, Nakanami N, Wake N, Masumoto K, Taguchi T 2007 Prenatal sonographic findings and biochemical assessment of amniotic fluid in a fetus with congenital chloride diarrhea. J Ultrasound Med 26: 1805–1807

Nakanishi T, Suzumori N, Mizuno H, Suzuki K, Sato T, Tanamura M, Suzuki Y, Suzumori K 2005 Elevated aldosterone in amniotic fluid and maternal blood has diagnostic potential in pregnancies complicated with a fetus of Bartter syndrome. Fetal Diagn Ther 20: 481–484

Matsushita Y, Suzuki Y, Oya N, Kajiura S, Okajima K, Uemura O, Suzumori K 1999 Biochemical examination of mother's urine is useful for prenatal diagnosis of Bartter syndrome. Prenat Diagn 19: 671–673

Acknowledgements

We thank all the clinical staffs, who provided us with amniotic fluid samples and who also provided the detailed follow-up of women and children.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

No financial assistance was received in support of the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garnier, A., Dreux, S., Vargas-Poussou, R. et al. Bartter Syndrome Prenatal Diagnosis Based on Amniotic Fluid Biochemical Analysis. Pediatr Res 67, 300–303 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181ca038d

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181ca038d

This article is cited by

-

Bartter’s syndrome: clinical findings, genetic causes and therapeutic approach

World Journal of Pediatrics (2021)

-

Hyperechogenic kidneys and polyhydramnios associated with HNF1B gene mutation

Pediatric Nephrology (2016)