Abstract

Compared with the full-term ductus arteriosus, the premature ductus is less likely to constrict when exposed to postnatal oxygen concentrations. We used isolated fetal sheep ductus arteriosus (pretreated with inhibitors of prostaglandin and nitric oxide production) to determine whether changes in K+- and CaL-channel activity could account for the developmental differences in oxygen-induced tension. In the mature ductus, KV-channels appear to be the only K+-channels that oppose ductus tension. Oxygen concentrations between (2% and 15%) inhibit KV-channel activity, which increases the CaL-channel-mediated increase in tension. Low oxygen concentrations have a direct inhibitory effect on CaL-channel activity in the immature ductus; this is not the case in the mature ductus. In the immature ductus, three different K+-channel activities (KV, KCa, and KATP) oppose ductus tension and contribute to its decreased tone. Oxygen inhibits the activities of all three K+-channels. The inhibitory effects of the three K+-channel activities decline with advancing gestation. The decline in K+-channel activity is not due to decreased K+-channel expression. Super-physiologic oxygen concentrations (≥30% O2) constrict the ductus by using calcium-dependent pathways that are independent of K+- and CaL-channel activities. Super-physiologic oxygen concentrations eliminate the difference in tensions between the two age groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The postnatal increase in arterial Pao2 plays an important role in ductus arteriosus constriction after birth. In the late gestation fetus, the changes in tension that accompany changes in oxygen concentration (within the physiologic range) appear to be due to changes in calcium entry through the ductus smooth muscle CaL channels (1,2). The CaL channels are regulated by the smooth muscle's membrane potential; calcium enters the cells when the cells are depolarized. K+-channels and Na+- K+-ATPases are the main determinants of the smooth muscle's membrane potential. A decrease in K+-channel activity, due to K+-channel blockade and/or down-regulation of channel expression, leads to membrane depolarization. Oxygen appears to inhibit K+-channel activity, leading to smooth muscle depolarization and increased calcium entry through the voltage-dependent CaL-channels (1,3,4).

Most studies suggest that voltage-gated K+-channels (KV channels) are responsible for oxygen's effect on membrane depolarization (3–5); ATP-sensitive K+-channels (KATP channels) and large conductance calcium-and-voltage sensitive K+-channels (KCa channels) have also been implicated as oxygen sensors (1,6). At the molecular level, K+-channels are composed of pore-forming α-subunits, which co-assemble with cytoplasmic regulatory/auxiliary β-subunits. Both KV α-subunits (Kv1.2, Kv1.5, Kv2.1, Kv3.1, Kv4.2, Kv4.3, and Kv9.3) and KV β-subunits have been shown to have oxygen-sensing capabilities (7). KATP channels [composed of KIR6 α-subunits and a sulfonylurea receptor (SUR2)] are responsive to hypoxic conditions and changes in oxygen concentration (8,9). KCa channels (composed of BKCa α-subunits and β1subunits) can be modulated by hypoxia and oxidant stress (6,9,10).

In contrast with the full-term ductus, the premature ductus is less likely to constrict when exposed to physiologic oxygen concentrations (11). Super-physiologic arterial oxygen concentrations, conversely, produce the same degree of constriction in vivo in the immature ductus as is observed in the mature ductus (11).

In this study, we used fetal sheep, to determine whether changes in K+- and CaL channel function were responsible for the changes in oxygen-induced ductus tension that occur within the physiologic as well as super-physiologic range of oxygen concentrations. We also wanted to determine whether developmental differences in K+-and CaL channel function could account for the differences in tension between the immature and mature ductus. We hypothesized that decreased K+-channel expression would account for the differences in tension between the immature and mature ductus. We used a pharmacologic and quantitative PCR approach to examine the roles of K+-channels and CaL channels in maintaining ductus tensions.

METHODS

Fifty late-gestation, mature sheep fetuses (mixed Western breed: 137 ± 2-d gestation, term = 145 d) and 47 immature fetuses (103 ± 2 d) were delivered by cesarean section and anesthetized with ketamine HCl (30 mg/kg IV) before rapid exsanguination. These procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

The fetal sheep ductus arteriosus was divided into 1-mm-thick rings (two to three rings per animal) and isometric tension was measured in a Krebs-bicarbonate solution [(×10−3 M): 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 0.9 MgSO4, 1 KH2PO4, 11.1 glucose, 23 NaHCO3 (pH 7.4)] containing indomethacin (5 × 10−6 M) and Nω-nitro-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 10−4 M), to inhibit endogenous prostaglandin and nitric oxide production, respectively (11). An oxygen electrode placed in the 10-mL organ bath, measured the oxygen concentration. The bath solution was equilibrated with gas mixtures containing 5% CO2 and was changed every 20 min. Rings were stretched to initial lengths (preterm = 5.2 ± 0.4 mm; late-gestation = 6.7 ± 0.6 mm) that produce maximal contractile responses when exposed to K+-Krebs solution (containing 0.1 M KCl substituted for an equimolar amount of NaCl), equilibrated with 95% O2 (11).

Once steady-state tension in 30% O2 was achieved (∼100-120 min), K+-Krebs solution (equilibrated with 95% O2) was used to measure the maximal contraction that could be developed by the ductus. After returning the rings to the initial modified Krebs solution, equilibrated with 15% O2, the rings were sequentially exposed to five different oxygen conditions: 2, 6, 15, 30, and 95% O2. We refer to bath oxygen concentrations between 2 and 15% as the “physiologic range” because they produce ductus tissue oxygen concentrations similar to the physiologic extremes experienced in vivo (12) [15% bath O2 concentration produces tissue oxygen concentrations similar to those achieved during the postnatal increase in arterial Po2; the 2% bath O2 concentration produces tissue oxygen concentrations similar to those needed to induce remodeling in vivo (11)]. Conversely, we considered the oxygen concentrations between 30 and 95% as the “super-physiologic range.”

After the oxygen dose-response curve, the rings were equilibrated with one of several experimental solutions before repeating the same oxygen dose-response curve. The solutions included: 10−5 M nifedipine (CaL-channel antagonist), 10−6 M BAY K8644 (CaL-channel agonist), calcium-free Krebs solution (containing 0.5 × 10−3 M EGTA without calcium), and K+-Krebs solution (to depolarize the muscle). Nifedipine (10−5 M) inhibits the effects of 10−6 M BAY K8644 (by 96 ± 5%) and K+-Krebs solution (by 87 ± 5%) when ductus rings are incubated in 15% O2 (2). Neither 10−5 M nifedipine, 10−6 M BAY K8644, nor K+-Krebs solution have any effect in the absence of extracellular Ca++ (2).

Ductus were also exposed to K+ channel antagonists before the second oxygen dose-response curve: 3 × 10−3 M 4-Aminopyridine (4AP) (KV-channel antagonist), 10−5 M glibenclamide (KATP channel antagonist), 50 × 10−9 M iberiotoxin (KCa-channel antagonist), 10−3 M tetraethylammonium ion (TEA) (KCa-channel antagonist), 10−6 M apamin (small conductance calcium-activated K+-channel antagonist), and10−2 M TEA (which produces 100% blockade of KCa-channels plus 50% blockade of Kv and KATP channels). The specificities of the above K+ channel antagonists have been reviewed in Ref. 13.

The ductus' contractile response to the oxygen dose-response curve does not change when it is repeatedly exposed in time matched control experiments (11). Sodium nitroprusside, 10−3 M, was added to each ring at the end of the experiment to determine its minimal tension.

The difference in tensions between any measured steady-state tension and the minimal tension produced by sodium nitroprusside was considered the Net active tension. The difference in tensions between the maximal contraction (produced by K+-Krebs/95% O2) and the minimal tension (with sodium nitroprusside) was treated as the maximal active tension (MAT) capable of being developed by the rings.

Active tensions are expressed as a percentage of the maximal active tension. Maximal active tensions were 16 ± 2 g in immature fetuses and 20 ± 3 g in mature fetuses. The ductus wet weights were as follows: 30 ± 9 mg, immature fetuses; 36 ± 10 mg, mature fetuses. Chemicals were from Sigma Chemical Co. Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

We used the TaqMan Universal PCR master mix of PE Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) to quantify the expression of the K+-channel subunits as previously described (14). Total RNA was isolated from the ductus of immature and mature fetal sheep (Table 1) and compared with RNA from the ductus of immature (125-d gestation) and mature (175-d gestation) fetal baboons (Papio sp., full term = 185-d gestation), and from immature (14-d gestation) and mature (19-d gestation) fetal mice (CD-1, full term = 19-d gestation) that were delivered by cesarean section and euthanized before breathing.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed by the appropriate Mann-Whitney test, t test, or by analysis of variance. Scheffe's test was used for post hoc analysis. Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Oxygen-induced tension in the mature ductus arteriosus.

The late gestation ductus arteriosus developed an active tension that was maintained by extracellular Ca++-dependent and extracellular Ca++-independent pathways (Fig. 1). Oxygen increased ductus tension through a mechanism that depended on the presence of extracellular calcium and could be blocked by high K+-containing Krebs solution (Fig. 1). After the removal of extracellular calcium, both oxygen and elevated K+ had only a negligible effect on ductus tension (Fig. 1A).

Effects of oxygen on active tension in the mature ductus arteriosus. Values represent active tension (mean ± SD) as a percent of maximal active tension. n = number of ductus rings from separate animals. Ductus were studied in the presence or absence of Panel A: Krebs solution (Control, □, n = 10), High K+-Krebs solution (▪, n = 8), calcium-free Krebs solution (▵, n = 10), or calcium-free/High K+-Krebs solution (▾, n = 8); Panel B: 10−5 M nifedipine (○, n = 10); Panel C: 10−6 M BAY K8644 (bull;, n = 7). *p < 0.05, experimental condition vs Control (□). Ductus tension at 6, 15, 30, and 95% O2 differed significantly (p < 0.05) from the tension at 2% O2, except for rings incubated in High K+-Krebs solution where tensions at 6, 15, 30, and 95% O2 were not significantly different from those at 2% O2; and in calcium-free Krebs, in calcium-free/High K+-Krebs solution, in nifedipine, and in BAY K8644 where tensions at 6% O2 were not significantly different from those at 2% O2.

Only a part of the oxygen-induced increase in ductus tension could be accounted for by changes in CaL-channel activity (Fig. 1B). The CaL-channel inhibitor, nifedipine, relaxed the ductus and nearly eliminated oxygen's effect on ductus tension in the physiologic range (2-15% O2), but only partially inhibited oxygen's effects in the super-physiologic range (≥30% O2). Similarly, BAY K8644, a CaL-channel opener, constricted the ductus and prevented oxygen from affecting ductus tension in the physiologic range, but only partially inhibited oxygen's effects in the super-physiologic range (Fig. 1C).

We used a combination of K+-channel inhibitors (4AP/TEA/glibenclamide), at concentrations that block KV, KCa, and KATP channel activities (13), to determine whether alterations in K+-channel activity could account for the oxygen-induced changes in ductus tension. Inhibition of K+-channel activity had the same effect on ductus contractility as the CaL-channel opener, BAY K8644 (Fig. 2A). The K+-channel inhibitors blunted the ability of oxygen to affect ductus tension in the physiologic range (2-15% O2), but only partially inhibited its effects in the super-physiologic range. The selective KCa and KATP inhibitors, iberiotoxin and glibenclamide, had no effect on tension. Only the KV inhibitor, 4AP, increased tension and blunted the oxygen-induced response (Fig. 2B, C, and D). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that, in the mature ductus, most of oxygen's contractile effects (in the physiologic range of oxygen concentrations) can be attributed to decreased KV-channels activity, which results in subsequent calcium entry through voltage-gated CaL-channels; conversely, at super-physiologic oxygen concentrations, oxygen appears to use additional mechanisms that depend on extracellular calcium entry but are independent of KV-channel and CaL-channel activities.

Effects of oxygen on active tension in the mature ductus arteriosus. Ductus were studied in the presence or absence of Panel A: 10−6 M BAY K8644 (bull;) or (3 × 10−3 M 4Ap + 10 × 10−3 M TEA + 10−5 M glibenclamide) (4AP/TEA/Glib) (▴, n = 7); Panel B: 3 × 10−3 M 4AP (▪, n = 7); Panel C: 50 × 10−9 M iberiotoxin (○, n = 5); Panel D: 10−5 M glibenclamide (▵, n = 6). *p < 0.05, experimental condition vs Control (□). Ductus tension at 6, 15, 30, and 95% O2 differed significantly (p < 0.05) from the tension at 2% O2, except for rings incubated with BAY K8644 and rings incubated with 4AP/TEA/glibenclamide, where tensions at 6% O2 were not significantly different from those at 2% O2.

Oxygen-induced tension in the immature ductus arteriosus.

The immature ductus also develops an active tension that is maintained by extracellular Ca++-dependent and Ca++-independent pathways. Extracellular Ca++-dependent pathways appear to play a smaller role in maintaining tension in the physiologic range of oxygen concentrations, in the immature ductus, than they do in the mature ductus (compare Figs. 1A and 3A). As the immature ductus becomes hypoxic, pathways that depend on extracellular Ca++ no longer appear to play a significant role in maintaining ductus tension. This appears to be due to a direct effect of low oxygen concentrations on CaL-channel activity. Conditions that usually open or close CaL-channels have either no effect (BAY K8644 and nifedipine) or a blunted effect (K+-Krebs solution) on tone at 2% O2 (Fig. 3). This contrasts with the mature ductus, where a significant proportion of the tension in 2% O2 is maintained by pathways that depend on the presence of extracellular Ca++, and the effects of nifedipine, BAY K8644 and High-K+ solution are minimally affected by changes between 2 and 30% O2 (Fig. 1).

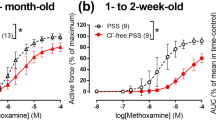

Effects of oxygen on active tension in the immature ductus arteriosus. Ductus were studied in the presence or absence of Panel A: Krebs solution (Control, □, n = 13), K+-Krebs solution (▪, n = 13), calcium-free Krebs solution (▵, n = 13), or calcium-free/High K+-Krebs solution (▾, n = 13); Panel B: nifedipine (○, n = 12); Panel C: BAY K8644 (bull;, n = 12). *p < 0.05, experimental condition vs Control (□). Ductus tension at 6, 15, 30, and 95% O2 differed significantly (p < 0.05) from the tension at 2% O2, except for rings incubated with calcium-free Krebs solution, in calcium-free/High K+-Krebs solution, and in nifedipine where tensions at 6% O2 were not significantly different from those at 2% O2.

We next examined the extent to which K+-channel activity affected tension in the immature and mature ductus. To account for the effect of low oxygen concentrations on the maximal tension that can be produced by K+-Krebs solution in the immature ductus (Fig. 3A), we expressed the net active tension (at a particular oxygen concentration) as a percentage of the net active tension produced by K+-Krebs solution at that particular oxygen concentration (Fig. 4).

Effects of oxygen and K+-channel inhibitors in the mature and immature ductus arteriosus. Values represent ductus tension (mean ± SD) (at a particular oxygen concentration) expressed as a percent of the net active tension produced by K+-Krebs solution at that particular oxygen concentration (Max Tension). Panel A: Ductus from mature (n = 7) and immature (n = 9) fetuses were studied in the presence or absence of 4AP/TEA/glibenclamide (Glib). Tensions in immature ductus, under Control (○) conditions (at 2 and 6% O2) differed significantly (p < 0.05) from tensions in mature ductus under Control (□) conditions; the tensions at higher oxygen concentrations (15, 30, and 95% O2) were not significantly different between the immature and mature ductus under Control conditions. When the rings were incubated in 4AP/TEA/glibenclamide, immature ductus (bull;) developed the same tensions as mature ductus (▪). Panel B: Immature ductus were studied in the absence (○) or presence (♦) of 4AP (n = 7); Panel C: Immature ductus were studied in the absence (○) or presence (♦) of iberiotoxin (n = 6); Panel D: Immature ductus were studied in the absence (○) or presence (▵) of glibenclamide (Glib, n = 6). *p < 0.05, experimental condition vs Immature Control. Ductus tension at 6, 15, 30, and 95% O2 differed significantly (p < 0.05) from the tension at 2% O2, except for rings incubated in 4AP/TEA/glibenclamide, where tensions at 6% O2 were not significantly different from those at 2% O2.

Tensions in the immature ductus (incubated under Control conditions, at oxygen concentrations between 2 and 15% O2) were significantly less than those in the mature ductus (Fig. 4A). Inhibition of K+-channel activity, with 4AP/TEA/glibenclamide, increased tension in both the mature and immature ductus and eliminated the difference in tension between the two age groups (Fig. 4A).

In contrast with the mature ductus, where only the KV channel inhibited tension (Fig. 2B, C, and D), tension in the immature ductus was inhibited by three types of K+-channels (KV, KCa, and KATP channels). In the immature ductus, KV, KCa, and KATP channel inhibitors blunted the effects of physiologic oxygen concentrations on ductus contractility (Fig. 4A-D). The K+ channel inhibitors did not prevent oxygen from constricting the immature ductus at super-physiologic oxygen concentrations (Fig. 4A). Apamin had no effect on either the immature or mature ductus (data not shown).

The inhibitory effects of KV, KCa, and KATP channels on contractility appeared to decline with advancing gestation because their selective antagonists were less effective in the mature compared with the immature ductus (Figs. 2 and 4). Their declining role was not due to decreased expression of K+-channel α- and β- subunits because their expression was either the same (BKCa) or higher (Kv1.2, Kv1.5, Kv 2.1, Kv 9.3, KIR6.1, Kvβ1.3, SUR2, and BKCaβ1) in the mature sheep ductus (Table 1).

Developmental changes in K+-channel α- and β-subunit expression also occurred in the baboon and mouse ductus; however, there was no consistent pattern of change in K+-channel expression across the species (Table 1). The Kv2.1 and the BKCaβ1 subunits were the only channel subunits that changed their expression in the same direction (increase) with advancing gestation (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Effects of physiologic and super-physiologic oxygen concentrations on the mature ductus.

The ductus arteriosus develops an active tension that consists of both extracellular Ca++-dependent and extracellular Ca++-independent components. Recent reports suggest that the extracellular Ca++-independent component of ductus tension may be due to rho kinase or tyrosine kinase-mediated Ca++ sensitization: a process whereby constriction occurs, independent of ongoing increases in cytosolic Ca++ (2,15–17). However, the changes in ductus tension that occur with changes in oxygen concentration appear to be mediated by pathways that regulate the entry of extracellular calcium into the ductus wall; removal of extracellular Ca++ eliminates the ability of oxygen to alter ductus tension (Fig. 1A).

In the late gestation fetus (in the absence of prostaglandin and nitric oxide production), changes in CaL-channel activity appear to be responsible for the changes in ductus tension that occur when oxygen concentrations are varied between 2 and 15% O2 (the physiologic range) (Fig. 1). The effects of physiologic oxygen concentrations on ductus tension are blunted by the removal of extracellular calcium, or the presence of CaL-channel inhibitors or activators (Fig. 1). In addition, the effects of physiologic oxygen concentrations on ductus tension appear to be because of their ability to inhibit K+-channel activity (Fig. 2A). Our observations are consistent with prior studies that found that oxygen increased Ca++ entry through voltage-dependent CaL-channels, by inhibiting K+ channel activity and depolarizing ductus smooth muscle (1,3,4,18,19).

Oxygen concentrations above the physiologic range (≥30% O2, the super-physiologic range) appear to inhibit most of the ductus' K+-channel activity because K+-channel inhibitors no longer affect ductus tension (Fig. 2). Although oxygen concentrations in the super-physiologic range eliminate the ability of K+-channel inhibitors to affect ductus tension, the converse is not the case; K+-channel inhibitors only partially inhibit oxygen's contractile effects in the super-physiologic range. Similarly, the CaL-channel opener, BAY K8644, and the CaL-channel blocker, nifedipine, only partially inhibit oxygen's effects in the super-physiologic range (Fig. 1). Therefore, additional extracellular Ca++-dependent mechanisms that are independent of K+- and CaL-channel activities, must affect ductus tension when oxygen concentrations increase above 30% O2. We speculate that these may involve other depolarization-sensitive calcium channels (like T-type channels) rather than mechanisms that alter Ca++ sensitivity: both high K+ and low Ca++ containing solutions block the effects of super-physiologic oxygen concentrations on ductus tension, whereas inhibitors of rho kinase and tyrosine kinase do not prevent super-physiologic oxygen concentrations from contracting the ductus (data not shown).

Effects of physiologic oxygen concentrations on the immature ductus.

When oxygen concentrations are in the physiologic range, the tensions developed by the immature ductus are significantly less than those developed by the mature ductus (Figs. 1A and 3A) (2,11). Our studies suggest that the major factor responsible for the difference in tensions between the immature and mature ductus is the way the immature ductus processes extracellular Ca++. In the absence of extracellular Ca++, the tension in the mature ductus drops to the same level as the immature ductus (32 ± 6% MAT) (Figs. 1A and 3A).

In the physiologic range of oxygen concentrations, oxygen affects the immature ductus' tension both by affecting the influx of extracellular calcium (Fig. 3) and by altering K+-channel activity (Fig. 4). The inhibitory effects of low oxygen concentrations on calcium entry appear to be limited to their effects on CaL-channels; low oxygen concentrations do not alter the contractile effects of agonists that increase intracellular calcium through pathways that are independent of CaL-channels (2).

The differences in tensions between the immature and mature ductus also appear to be due to differences in K+ channel activity. Inhibition of K+-channel activity, with 4AP/TEA/glibenclamide, increased ductus tension in both the mature and immature ductus and eliminated the difference in tensions between the two age groups (Fig. 4A). Three K+-channels (KV, KCa, and KATP) appear to play a role in inhibiting tension in the immature ductus (Fig. 4B, C, and D). The inhibitory effects of the KCa, and KATP channels appear to decline with advancing gestation, because their selective antagonists have less of an effect on ductus tension as the fetus matures (compare Figs. 2B-D and 4B-D). The declining effects of K+-channel activity on ductus contractility is not due to decreased expression of K+-channel α- or β-subunits because their expression is increased, if anything, with advancing gestation (Table 1).

Effects of super-physiologic oxygen concentrations on the immature ductus.

When oxygen concentrations increase into the super-physiologic range, in the immature ductus, the inhibitory effects of the KV, KCa, and KATP channels appear to be blocked because their respective inhibitors (4AP, iberiotoxin, and glibenclamide) no longer have any effect on ductus contractility (Fig. 4). Whether the effects of super-physiologic oxygen concentrations are mediated through changes in the K+-channels themselves or through changes in commonly shared downstream pathways will have to await the results of future electrophysiological studies.

Super-physiologic oxygen concentrations eliminate the difference in tensions between the mature and immature ductus (Fig. 4A). These results may explain why super-physiologic arterial oxygen concentrations are able to constrict the immature ductus to the same degree as the mature ductus, in vivo (11).

Oxygen responsiveness in the immature ductus and Kv channel expression.

Prior studies, in rabbits, suggest that reduced expression of the oxygen-sensitive KV-channel α-subunits, Kv1.5 and Kv2.1, lead to impaired oxygen-induced constriction in the immature ductus (4). In these studies, ex vivo transfer of the genes for Kv1.5 or Kv2.1 into the immature ductus partially rescued the contractile response to oxygen (4). In contrast, a recent study, performed in rats, found exactly the opposite results [i.e. expression of KV α-subunits was greater in the immature than the mature ductus (20)]. We examined the developmental expression of several KV-channel α-subunits in sheep, baboon, and mouse ductus to determine whether decreased KV-channel α-subunit expression could lead to impaired oxygen-induced constriction in other species. The expression of several of the KV α-subunits was reduced in the immature ductus in each of the species; however, only the Kv2.1 α-subunit was consistently reduced in all three species (Table 1).

Although decreased KV α-subunit expression may lead to decreased oxygen-induced constriction in the immature rabbit ductus (4), it did not lead to a decreased contractile response to oxygen in the immature sheep ductus. In fact, changes in oxygen concentration (in the physiologic range) produced larger changes in tension in the immature ductus than in the mature ductus (Fig. 4A: Immature Control versus Mature Control). In addition, K+-channel inhibition did not prevent oxygen from constricting the immature sheep ductus at super-physiologic oxygen concentrations (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we speculate that other mechanisms may play a more significant role in the diminished responsiveness of the immature ductus to oxygen. These may include increased KCa and KATP activity (Fig. 4), impaired calcium [CaL (2,21) or store-operated (17)] channel function, decreased rho kinase activity (2,15–17,21), decreased endothelin production (22), and/or increased sensitivity to prostaglandins and nitric oxide (14,23,24).

References

Nakanishi T, Gu H, Hagiwara N, Momma K 1993 Mechanisms of oxygen-induced contraction of ductus arteriosus isolated from the fetal rabbit. Circ Res 72: 1218–1228

Clyman RI, Waleh NS, Kajino H, Roman C, Mauray F 2007 Calcium-dependent and calcium-sensitizing pathways in the mature and immature ductus arteriosus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1650–R1656

Tristani-Firouzi M, Reeve HL, Tolarova S, Weir EK, Archer SL 1996 Oxygen-induced constriction of rabbit ductus arteriosus occurs via inhibition of a 4-aminopyridine-, voltage-sensitive potassium channel. J Clin Invest 98: 1959–1965

Thebaud B, Michelakis ED, Wu XC, Moudgil R, Kuzyk M, Dyck JR, Harry G, Hashimoto K, Haromy A, Rebeyka I, Archer SL 2004 Oxygen-sensitive Kv channel gene transfer confers oxygen responsiveness to preterm rabbit and remodeled human ductus arteriosus: implications for infants with patent ductus arteriosus. Circulation 110: 1372–1379

Hayama E, Imamura S, Wu C, Nakazawa M, Matsuoka R, Nakanishi T 2006 Analysis of voltage-gated potassium channel beta1 subunits in the porcine neonatal ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res 59: 167–174

Park MK, Lee SH, Lee SJ, Ho WK, Earm YE 1995 Different modulation of Ca-activated K channels by the intracellular redox potential in pulmonary and ear arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. Pflugers Arch 430: 308–314

Yuan JX 2001 Oxygen-sensitive K(+) channel(s): where and what?. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1345–L1349

Brayden JE 2002 Functional roles of KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 29: 312–316

Liu Y, Gutterman DD 2002 Oxidative stress and potassium channel function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 29: 305–311

Korovkina VP, England SK 2002 Molecular diversity of vascular potassium channel isoforms. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 29: 317–323

Kajino H, Chen YQ, Seidner SR, Waleh N, Mauray F, Roman C, Chemtob S, Koch CJ, Clyman RI 2001 Factors that increase the contractile tone of the Ductus Arteriosus also regulate its anatomic remodeling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R291–R301

Clyman RI, Chan CY, Mauray F, Chen YQ, Cox W, Seidner SR, Lord EM, Weiss H, Wale N, Evan SM, Koch CJ 1999 Permanent anatomic closure of the ductus arteriosus in newborn baboons: the roles of postnatal constriction, hypoxia, and gestation. Pediatr Res 45: 19–29

Nelson MT, Quayle JM 1995 Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 268: C799–C822

Waleh N, Kajino H, Marrache AM, Ginzinger D, Roman C, Seidner SR, Moss TJ, Fouron JC, Vazquez-Tello A, Chemtob S, Clyman RI 2004 Prostaglandin E2-mediated relaxation of the ductus arteriosus: effects of gestational age on g protein-coupled receptor expression, signaling, and vasomotor control. Circulation 110: 2326–2332

Costa M, Barogi S, Socci ND, Angeloni D, Maffei M, Baragatti B, Chiellini C, Grasso E, Coceani F 2006 Gene expression in ductus arteriosus and aorta: comparison of birth and oxygen effects. Physiol Genomics 25: 250–262

Kajimoto H, Hashimoto K, Bonnet SN, Haromy A, Harry G, Moudgil R, Nakanishi T, Rebeyka I, Thebaud B, Michelakis ED, Archer SL 2007 Oxygen activates the Rho/Rho-kinase pathway and induces RhoB and ROCK-1 expression in human and rabbit ductus arteriosus by increasing mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species. A newly recognized mechanism for sustaining ductal constriction. Circulation 115: 1777–1788

Hong Z, Hong F, Olschewski A, Cabrera JA, Varghese A, Nelson DP, Weir EK 2006 Role of store-operated calcium channels and calcium sensitization in normoxic contraction of the ductus arteriosus. Circulation 114: 1372–1379

Roulet MJ, Coburn RF 1981 Oxygen-induced contraction in the guinea pig neonatal ductus arteriosus. Circ Res 49: 997–1002

Michelakis E, Rebeyka I, Bateson J, Olley P, Puttagunta L, Archer S 2000 Voltage-gated potassium channels in human ductus arteriosus. Lancet 356: 134–137

Wu C, Hayama E, Imamura S, Matsuoka R, Nakanishi T 2007 Developmental changes in the expression of voltage-gated potassium channels in the ductus arteriosus of the fetal rat. Heart Vessels 22: 34–40

Thebaud B, Wu XC, Kajimoto H, Bonnet S, Hashimoto K, Michelakis ED, Archer SL 2008 Developmental absence of the O2 sensitivity of L-type calcium channels in preterm ductus arteriosus smooth muscle cells impairs O2 constriction contributing to patent ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res 63: 176–181

Coceani F, Armstrong C, Kelsey L 1989 Endothelin is a potent constrictor of the lamb ductus arteriosus. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 67: 902–904

Liu H, Manganiello V, Waleh N, Clyman RI 2008 Expression, activity and function of phosphodiesterases in the mature and immature ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res 64: 477–481

Seidner SR, Chen Y-Q, Oprysko PR, Mauray F, Tse MM, Lin E, Koch C, Clyman RI 2001 Combined prostaglandin and nitric oxide inhibition produces anatomic remodeling and closure of the ductus arteriosus in the premature newborn baboon. Pediatr Res 50: 365–373

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Christine Roman, Naoko Brown, Jackie Coalson, Vicki Winter, personnel at the BPD Resource Centre, Alan Jobe, Machiko Ikegami, and John Newnham for help in obtaining tissues.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by grants from U.S. Public Health Service (NIH grants HL46691, HL56061, HL77395, HL52636 BPD Resource center and P51RR13986 baboon facility support) and by a gift from the Jamie and Bobby Gates Foundation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Waleh, N., Reese, J., Kajino, H. et al. Oxygen-Induced Tension in the Sheep Ductus Arteriosus: Effects of Gestation on Potassium and Calcium Channel Regulation. Pediatr Res 65, 285–290 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819746a1

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819746a1