Abstract

Physicians are living longer and are healthier than in previous times. The opportunity to use their experience, expertise, and wisdom after what would be “normal” retirement age needs to be explored. The object of this study was to survey senior academic pediatricians and pediatric department chairs to define the present status of pediatricians who are in academic settings and are older than 65 y, to explore the options that are open to pediatricians who are older than 65 y for continuing to use their skills, and to increase the awareness of the unused potential that exists among senior pediatricians. Structured questionnaires were sent to the 1444 members of the American Pediatric Society (APS) and to the 148 pediatric department chairs of the medical schools in the United States and Canada to identify current practices concerning retirement and utilization of senior pediatricians. Thirty-five percent of APS members and 40% of chairs of pediatrics responded. The responding APS members were interested in exploring avenues to continue to use the skills that they had developed. The responding pediatric chairs reported that they were constrained from supporting their senior faculty members by institutional pressures for space, salary monies, and the need to recruit new faculty members. However, they recognized the value of senior pediatricians. The skills and expertise of senior pediatricians (and probably other physicians) are often not used after the usual age of “retirement.” New programs and pathways need to be developed not only to use the resource of these skills but also to enhance the health and sense of satisfaction of senior pediatricians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

During the last century, life expectancy in the developed world rose from ∼47 y to between 73 and 83 y—an extra 30 y. Improved pediatric care can claim most of that increase. Child health care workers gained a great deal of new knowledge and practical know-how during the past century. Senior pediatricians who retire these days have enormous experience, expertise, and pragmatic insights—and probably have an additional 15–25 y to live. Most are in good health. An exciting challenge is how to use their hard-earned experience without impinging on the right to “retire.”

The American Pediatric Society (APS) is the oldest and most senior pediatric academic organization in North America. Its members have been chosen on the basis of exceptional contributions to academic pediatrics but probably represent <5% of academic pediatricians. Many have been deans, department chairs, and division heads. All have specialized expertise and knowledge about training, education, clinical care, research, and/or administration. They are probably not completely representative of all academic pediatricians. A recent review of membership indicated that half were 60 y or older, and many had retired. However, in view of increasing life expectancy and the looming shortage of experienced specialty pediatricians, the question arises as to whether new alternative approaches to retirement and flexible career planning should be considered. A search of the medical and academic literature reveals that although a few articles (1–14) discuss physicians' retirement, no articles discuss or explore the range of career/postcareer options that are available to “retiring” physicians and capitalize on the skills that they have developed.

The APS council decided to undertake a questionnaire of its members concerning these issues. As reported below, the results of the questionnaire suggested that additional information was needed concerning the policies and procedures around retirement that presently exist in the institutions that house academic pediatricians. Consequently, the pediatric chairs of North American medical schools [Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs (AMSPDC)] were also surveyed. This article includes the results for both surveys. The term “senior” in this article is used to refer to the pediatricians who are older than 65 y, because we have learned that the terms “retired” and “emeritus” do not capture the additional career potentials of these individuals (see Table 1).

METHODS

The APS questionnaire was developed by several members of the APS Council and reviewed by the council. The questions for the APS members consisted of 10 questions concerning current status, desired information about career/avocation options after retirement, expected needs after retirement, and preparations for retirement; additional comments were encouraged. The questionnaire and responses to specific questions can be obtained from the author on request The questionnaires could be answered anonymously, or the respondent could self-identify. Most respondents answered all questions, although younger members might indicate that a particular questions was not of concern to them. The results of the survey could be requested as well as an opportunity to volunteer to be part of future APS workshops. A reminder was sent 2 mo after the original mailing.

The questionnaire for the chairs of pediatrics consisted of 30 questions concerning policies and their experience with retired or retiring faculty members. Again, there was a reminder and encouragement to make additional comments. (The questionnaire and the range of responses to specific questions can be obtained from the author on request.)

RESULTS

APS membership responses.

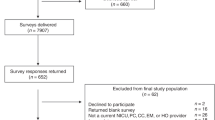

The APS membership questionnaire had a 35% response rate. Proportionally, a greater number of emeritus APS members and women members responded compared with the other APS members.

Of the 1444 APS members, 509 responded to the questionnaire. Of the 957 active (dues paying) members, 305 responded, and 204 of the 444 emeritus (over age 65 and non–dues paying) members responded. A total of 405 of the 1197 male APS members responded, and 106 of the 247 female APS members responded. The average age of respondents was 65 y, and the range of the age of respondents was from 39 to 94 y.

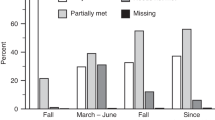

Seventeen percent of APS respondents characterized themselves as completely retired, 17% reported being retired but were still active in pediatrics, 15% were planning to retire in the next 1–5 y, 15% planned to retire within the next 5–7 y, 15% planned never to retire, and 22% classified themselves as “other” (mainly too young to have thought about the issue). There were no real differences in the responses when separated into subgroups.

When asked to identify potential APS activities that the respondents would like to see developed to help in their retirement planning, opportunities in international health and international education were the most frequently identified topics, with almost 80% of members identifying them. The opportunity to provide consultant services using their expertise was identified as the second most common area about which they wished to have more information. The third most frequently selected area was the development of an APS fellowship for pediatricians who are older than 65 y that would be aimed at exploring the ways in which to use senior pediatricians to improve the health of children and youth. More than 50% of individuals who answered the questionnaire identified interest in the option of doing locums for clinically active academic pediatricians so that the regular faculty would be able to take sabbaticals, study leaves, or holidays.

When planning retirement or their next career phase, APS member respondents identified areas that they were interested in exploring, but from their comments, they often anticipated that they might need to acquire additional skills to move into the new area of interest. In order, starting with the most frequently identified area, they were 1) editing, reviewing, and writing; 2) international health; 3) working with research networks and in research collaborations; 4) teaching; 5) as consultants to business; 6) medical/legal consultation; and 7) working with professional organizations.

Respondents were asked to identify (no matter what their present status) the things that would be important if they were to continue to work at the medical school after the age of 65 y. More than 50% indicated, in descending order of importance to them, that they wanted to attend conferences and rounds, they would like to have an office, they would need a computer or equipment that would make it possible for them to work, and they would like decreased “on-call.” Fewer than 50% of respondents identified the following as important to them, in descending order: income, that their fees would be paid for memberships or insurance, concerns about their ability to care adequately for patients, and their need for access to patient information

The APS member respondents were generous with their additional comments. There were a number of comments about the importance of needing more information to plan for developing options for their later career. Respondents reported that they believed that they still had contributions to make but that they had been treated in a way that made them feel unwanted and unvalued. Many expressed a desire to continue to teach at all levels, from medical students to subspecialty trainees. Many expressed a desire to continue to follow their own patients to understand the natural history of the diseases that they had been treating. Pay for these activities was not a priority, but because being paid was a reflection of being valued, it was desirable.

In response to the question about preparation for retirement and what types of information were needed, the most important areas noted were financial matters and health care arrangements. This information turns out to be readily available in most academic settings through the human resources departments. In addition, the articles that have been published about retirement usually cover these topics (1–12). However, additional areas of importance to the respondents were topics on which information is less readily available:

-

1

How to obtain continued access to libraries, rounds, and conferences at the medical school, hospital, or department of pediatrics

-

2

How to have or arrange access to have continued contact with trainees

-

3

How to have access to materials or equipment that would allow them to continue writing and publishing

-

4

How to have access to continuing research projects in which they had been involved

-

5

How to change the description of their status (stated title) to emeritus or equivalent in their institution

Chairs of departments of pediatrics responses.

The survey of 148 chairs of university departments of pediatrics in North American medical schools had a 40% response rate from the departmental chairs at a broad spectrum of institutions. Among those who responded, 34% had been chair for 1–5 y, 38% had been chair for 5–10 y, 20% had been chair for 10–15 y, and 9% had been chair for >15 y.

With regard to the size of their departments, <27% of chairs who responded had departments of <50 faculty members, 20% had departments of 50–100 faculty members, 22% had departments of 100–150 individuals, and 24% had departments of >150 faculty members. A total of 87% of respondents had >50% of their department members who were full time. Thus, they were a representative spectrum of the chairs of pediatrics from the North American medical schools.

When asked to identify the number of older faculty within their department (i.e. individuals who might need to be thinking about their senior years), 62% of chairs indicated that 20% of their members were 50–60 y old. Only 11% of the department chairs had <10% of individuals who were older than 60 y; 41% of department chairs had >5% of their faculty who were older than 60 y. One third of the department chairs who responded had more than eight members of their active department members who were older than 65 y. One third of department chairs had up to six members of their department who were older than 65 y. One third of the chairs who answered the questionnaire had in their department two or fewer individuals who were older than 65 y.

Most institutions in North America have tenure as part of their academic track. However, most departments also have nontenure track faculty as part of their departments. Most of the new medical schools and medical center–based institutions are not establishing tenure but rather have a contract system. In the United States, it seems that no schools have an expected age of retirement because this would be illegal. There are a few Canadian schools for which the Supreme Court of the province has upheld retirement at age 65 as constitutional. These schools have a required and expected age of retirement or of becoming emeritus faculty that is well known to the academic pediatricians.

With regard to the issue of being able to discuss retirement with department members, department chairs expressed some concern that this could be viewed as “ageism.” Twenty-two percent of department chairs indicated that they felt some constraint about discussing retirement with department members. Ten percent indicated that they were careful in how they discuss retirement, and 68% of department chair respondents said that they felt no constraint.

When department chairs were queried about their institutions' policy on retirement, 33% of chairs indicated that there was some type of policy. Of that 33%, 58% had an institutional policy, 21% had institutional incentives to encourage seniors to retire, and in 20% of departments, the chair had developed a consistent policy. Forty percent of chairs had a completely ad hoc approach to dealing with the retirement of their senior department members. Twenty-seven percent of chairs indicated that they had no policy in place. When asked whether they could expect to receive help with issues around retirement of the pediatric senior faculty from their dean or the other department chairs at their institution, only 20% indicated that they would expect to receive help. However, all expressed that there were institutional pressures exerted on the chairs to move senior pediatricians along out of the department. Sixty-three percent of chairs indicated that there were economic pressures, 51% indicated space pressures, and 33% indicated that there were institutional pressures.

The chairs are responsible for providing a broad range of educational experiences. It turns out that 68% of chairs retain or rehire retired senior pediatricians (and pay them) to help with departmental educational needs. No chairs indicated that they did not rehire senior pediatricians. With regard to how long these senior pediatricians remained active, the chairs indicated that approximately half stayed for 1–3 y after retirement, but 40% of the chairs indicated that they had senior pediatricians staying on between 4 and 10 y. Some departments have a policy of phasing out the rehired/retired senior pediatricians over a 3-y period. The types of jobs and services for which senior retired pediatricians were rehired include 54% for clinical service, 50% for mentoring, and 33% for research.

When asked what the senior faculty had contributed to the department, 80% of chairs indicated very positive contributions. In descending order of frequency of the chairs responses, teaching, clinical work, historical perspective, mentoring, political advice and insight, administration, committees and projects, research, and reviewing divisions.

Consulting national role and networking.

Certain regions of North America are attractive retirement areas, and so when asked whether retired senior pediatricians had moved into their area and contacted them, 31% of chairs indicated that they had been contacted. These were primarily in California and Florida. However, the chairs indicated that the individuals who had moved into the area primarily wished to attend conferences and very occasionally to actually work.

When asked what senior pediatricians wanted to have access to over the age of 65, the following is, in the order of top requests, what the chairs had been asked for: an office, their own health care paid for, secretarial support, access to teaching, continuing income, and telephone. This order is different from that expressed by APS members over the age of 60 (see Table 2).

Few departments provide facilities for senior pediatricians. Only 18% of departments had facilities designated for senior faculty, and 50% of those were related to offices for individuals who were continuing to work. Only three departments had an area for senior pediatricians to meet. Only one department had a committee to deal with seniors, and only one department sponsored a senior pediatrician meeting in a social setting. Eighty percent of chairs indicated that the department's institutional human resources department had information about retirement, but the information was almost entirely regarding financial matters.

When asked to identify problems with senior faculty, chairs responded that the number one problem related to senior pediatricians was their inability to recognize that they were failing. The second most common problem was related to the failing health of the senior pediatrician. The third most common problem was that the individuals wanted financial support. Some senior individuals were noted to have decreasing productivity: not really wanting to work, having “burned out,” or not wanting to take “on-call.” The chairs acknowledged that only a very few senior individuals were really a problem, being obstructionist or bitter.

When asked how senior faculty members are evaluated, 63% of the chairs indicated that they were evaluated in the same manner as other department members; 12% of chairs had a special way for evaluating senior/emeritus members, and 25% had no evaluation of senior department members.

The chairs agreed that the ideal age for “complete” retirement and absenting from the department was ∼70 y. There was almost a bell-shaped curve among their responses, with 70 y of age at the peak as the ideal age. Twenty-one percent of chairs indicated that 65 was ideal, 39% of chairs indicated 70, and 13% indicated 75 y of age.

Many positive aspects to senior pediatricians were identified by the chairs. Most chairs suggested that senior pediatricians had to be dealt with individually. They recognized that most had an enormous amount to contribute and only a few were very difficult (see Tables 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

The combination of increased longevity and good health among academic pediatricians in the developed world together with an increasing need for experienced academic pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists presents a unique opportunity to develop ways to use the skills and experience of senior pediatricians after what would be their usual age of retirement. In addition, the senior academic pediatricians surveyed want to know what kinds of options are available for them to continue to make professional contributions, both to their department and to the health of children and youths around the world. The survey of APS members indicates that they want to continue to use the skills that they have developed during their professional career after the usual age of retirement. Information about options and the possibility of a “new lifestyle” is apparently not readily available. In fact, it seems that needed is a shift in the mindset that encourages physicians to begin to think in their mid-career about options for their later years that may use the skills that they have developed during their career (1–14).

The two sets of questionnaires reported here had a surprisingly good response rate for a mailed questionnaire, suggesting that planning for retirement, a new career, or continuation in academic life is an important topic to academic pediatricians and may need to begin in the mid-50s. Literature on physician response to surveys (15) indicates that mail surveys without incentives or telephone follow-up can expect a 14–33% response. The surveys presented in this report were not developed for statistical analysis but rather are reported here for information and planning.

Most academic pediatricians and other physicians in the past have gone about beginning to think of the retirement process between 65 and 70 y of age (10–12). One survey of surgeons raised the issue of when and at which age physicians should stop performing procedures (10). The literature that is available suggests that 20–40% of physicians want to continue doing exactly what they have always done, and 20–40% want to completely leave the medical/health field (2,12). However, it seems the other 40–60% want to explore other options, particularly other lifestyles that allow them to use the skills and experience that they have acquired.

The pediatric chairs survey indicates that some pediatricians may wish to retire even earlier than 65 y of age because they are either “burned out” or have failed to keep up with new developments. Alternatively, some pediatricians may be able to continue in the same capacities in which they have been engaged for many years after the usual retirement age.

Clearly, the chairs value the contributions of the senior faculty members (Tables 3 and 4). They frequently ask them to provide service in needed areas and have paid for these services. However, the senior faculty often seem to believe that they have moved outside the mainstream and are somewhat disenfranchised. Although they may no longer be on the cutting edge, their experience and perspectives are often of great value. Perhaps thought can be given to how to appropriately acknowledge this type of contribution.

It should be noted (Table 2) that the perceptions and emphasis of the chairs and the senior pediatricians about what senior pediatricians desire in their working conditions is different. The chairs seem to think that what is wanted are things that cost money, whereas the senior pediatricians seem to want to stay involved and be valued. The process must be individualized to the interests and needs of a particular senior pediatrician. However, there seems to be a real need for developing an approach at an earlier stage that allows access to information about options as well as the development of new skills for a variety of nontraditional roles.

Table 4 lists areas the chairs identified in which their senior pediatricians have made or could make contributions because of their experience and life skills. These represent some of the areas that are probably particularly suited to the senior, experienced, academic pediatrician.

It seems that several resources need to be developed (see Table 5) to use the already developed skills of senior pediatricians and allow them the flexibility to identify the opportunities and new directions that they wish to explore.

First, there is the need expressed by senior APS members to develop workshops and information sources to share their experiences and become knowledgeable about the opportunities that exist. As this type of information is developed, it can be disseminated through courses, articles, and the development of dedicated web sites, as well as by the “testimonials” of individual experiences in articles, books, and presentations. The APS and pediatric department chairs can play a role in developing sources of this type of information (e.g. courses at the academic pediatric and other pediatric meetings, a web site) and alerting their members to its availability. To accomplish a more appropriate transition, access to this kind of information is probably needed mid-career. Chairs can play an important role in the careers of their faculty members by raising these issues with department members in their 50s.

Second, many practical and emotional aspects to the shift in career occur as senior physicians “retire” or become “emeritus” (1). Human resources departments in tertiary care hospitals and medical schools clearly need to develop information about new or alternative career styles in addition to financial and health care information for those who are planning “retirement” (1,9,13,14). Medical professional associations often have information about the legal obligations that physicians have to their patients and to their records, but rarely do such organizations encourage older members to plan to use their accumulated skills (8). Energetic and experienced seniors will be looking for new options that have not previously been possible for most physicians over 65 y of age.

Third, there is also a need to develop a method of evaluating the contributions made by senior pediatricians in academic departments (as well as elsewhere) so that they can receive realistic feedback and work on ways to be more useful if that is appropriate. The current process of evaluating faculty performance (16) may not be appropriate for senior pediatricians if they are performing or providing alternative roles. In addition, it will be necessary, if more senior pediatricians remain in academic departments, to develop age-specific standards, expectations, and work loads (e.g. less on call, working morning only) (3,7).

There are many limitations to these two surveys; however, even though they reflect only academic, older, and mainly male pediatricians, the issues ring true for physicians in general. As the baby boomers age, there will be more and more physicians looking at second career options. This requires developing guidelines for the age at which one can gracefully retire, change work style and lifestyle, and change the focus of one's career. An individual who is “burned out” with acute care may turn out to be a superb writer (11) or consultant to a business. Specialized skills are required in almost every type of job; therefore, the opportunity to develop new skills will certainly be needed for the most effective utilization of senior pediatricians. In addition, developing new ways to express appreciation and respect for the skills and insights of senior pediatricians (as well as other physicians) will undoubtedly provide them with a sense of value and contribute to their personal well-being.

A great deal of literature on aging suggests that staying active (physically and mentally) leads to better health and a sense of well-being (1,2,5,6). Academic pediatricians and other physicians (12) retire for both emotional and practical, as well as positive and negative reasons. Because of the pressures exerted by the pediatric department chairs (secondary to the pressures that the chairs themselves experience) encouraging senior faculty to retire, there may be unnecessary loss of self-esteem and disenfranchisement experienced among senior academic pediatricians. Clearly, the attitude with which a physician “retires” will influence the next phase of life. Changes in tenure policy and mandatory retirement will undoubtedly lead to increased interest in the variety of career pathways that are available (17–19).

In the past, professional articles that described physician retirement suggested developing hobbies (2,5,13,14). This may well be a good idea; however, the present studies suggest that many avenues also exist for creatively using the unique and valuable skills that have been developed during the careers of senior academic pediatricians.

Abbreviations

- AMSPDC:

-

Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs

- APS:

-

American Pediatric Society

References

Lees E, Liss SE, Cohen IM, Kvale JN, Ostwald SK 2001 Emotional impact of retirement on physicians. Tex Med 97: 66–71

Rowe ML 1989 Health, income, and activities of retired physicians. NY State J Med 89: 450–453

Greenfield LJ, Proctor MC 1994 Attitudes toward retirement. A survey of the American Surgical Association. Ann Surg 220: 387–390; discussion

Grauer H, Campbell NM 1983 The aging physician and retirement. Can J Psychiatry 28: 552–554

Vaillant GE 2002 Aging Well: Surprising Guideposts to a Happier Life from the Landmark Harvard Study of Adult Development. Little, Brown, Boston, MA

Sharon IC 1987 Don't be afraid to retire!. J Postgrad Med 81: 117–118: 120

Rowland AB 1983 Age discrimination in retirement: in search of an alternative. Am J Law Med 8: 433–480

Martin D 1991 Is there life after medicine? Texas physicians talk about retirement. Tex Med 87: 36–45

MacMahon DG 1994 What's so special about being 65? The challenge of facing eldercare departments. JR Soc Med 87: 80–82

Virshup B, Coombs RH 1993 Physicians' adjustment to retirement. West J Med 158: 142–144

Mills JW 1995 Retiring from medicine: the grief process. Pa Med 98: 6

Wakeford R, Roden M, Rothman A 1986 General practitioners' retirement plans and what influences them. BMJ 292: 1307–1310

Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G 1997 The older psychiatrist and retirement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 12: 233–239

Miscall BG, Tompkins RK, Greenfield LJ 1996 ACS survey explores retirement and the surgeon. Bull Am Coll Surg 81: 18–25

Kellerman SE, Herold J 2001 Physician response to surveys: a review of literature. Am J Prev Med 20: 61–67

Bland CJ, Wersal L, VanLoy W, Jacott W 2002 Evaluating faculty performance: a systematically designed and assessed approach. Acad Med 77: 15–30

Forster P 1993 The fortysomething barrier: medicine and age discrimination. BMJ 306: 637–639

Jones RF 1991 The end of mandatory retirement and its implications for academic medicine. Acad Med 66: 711–718

Jones RF 1993 Three views on faculty tenure in medical schools. Acad Med 68: 588–593

Acknowledgements

These studies would not have been possible without the help and support of the APS office (Kathy Cannon in particular), the APS members, and the chairs of pediatrics of North American medical schools (AMSPDC). Special thanks to Drs. Cynthia Curry, William Gibson, and Rodney Howell and the reviewers for helpful suggestions and to Kimi Tanaka for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, J. The Challenge of Developing Career Pathways for Senior Academic Pediatricians. Pediatr Res 57, 914–919 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1203/01.PDR.0000158014.46884.E5

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/01.PDR.0000158014.46884.E5

This article is cited by

-

A systematic review of physician retirement planning

Human Resources for Health (2016)

-

Commentary: Physician Retirement and Physician Shortages

Journal of Community Health (2009)