Abstract

The compelling evidence linking small size at birth with later cardiovascular disease has renewed and amplified a clinical and scientific interest in the determinants of fetal growth. Although the effects of maternal nutrition on fetal growth have been extensively studied, comparatively little is known about the effects of maternofetal hypoxia. This study tested the hypothesis that in highland regions, high altitude rather than maternal economic status is associated with reduced and altered fetal growth by investigating the effects of high altitude versus economic status on birth weight and body shape at birth in Bolivia. Bolivia is geographically and socioeconomically unique. It contains several highland (>3500 m above sea level) and lowland (<500 m) cities that are inhabited by very economically divergent populations. Birth weight, body length, and head circumference were compared between a high- (n = 100) and low- (n = 100) income region of La Paz (3649 m; largest high-altitude city) and a high- (n = 100) and low- (n = 100) income region of Santa Cruz (437 m; largest low-altitude city). In addition, the frequency distribution across the continuum of birth weights was plotted for babies born from high- and low-income families in La Paz and Santa Cruz. Mean birth weights were lower in babies from La Paz than in babies from Santa Cruz in both high- and low-income groups. The cumulative frequency curve across all compiled birth weights was shifted to the left in babies from La Paz compared with those from Santa Cruz, regardless of economic status. The frequency of low birth weight (<2500 g) was higher in babies from La Paz than from Santa Cruz in both high- and low-income groups. In addition, at high altitude but not at low altitude, high income was associated with an increase in the head circumference:birth weight ratio. These findings suggest that high altitude rather than economic status is associated with low birth weight and altered body shape at birth in babies from Bolivia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Epidemiologic studies of populations in England and Wales have shown an association between small body size at birth and increased risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood (1, 2). These findings have been replicated in the Unites States (3), Sweden (4), Finland (5), The Netherlands (6), Croatia (7), India (8), and Japan (6). Studies of birth weights of relatives (9, 10), together with evidence from animal cross-breeding experiments (11–13), have led to the conclusion that the predominant influence on fetal growth is the intrauterine environment rather than the fetal genotype. These observations have led to “the fetal origins hypothesis,” which proposes that cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes originate through adaptations that the fetus makes when it is undernourished. These adaptations, which include slowing of growth, permanently change the structure and function of the body (14). Hence, it is not surprising that these contentions have renewed and amplified a clinical and physiologic interest in which conditions during pregnancy lead to fetal growth retardation.

Although it is accepted that the most common challenges limiting fetal growth are reduced nutrient and oxygen delivery to the fetal circulation (15), the partial contributions of each of these substrates to fetal growth impairment remain to be determined. Several studies have shown that poor maternal nutrition is associated with reduced birth weight in humans (16–19), rats (20–22), and sheep (23, 24) and that the extent of the reduction depends on the severity, duration, and timing of the challenge (23, 24). Relatively less information is available about the effects on body size at birth of maternofetal hypoxia, independent of changes in maternal nutritive state.

In human populations, maternofetal hypoxia occurs most commonly during the hypobaric hypoxia of pregnancy at high altitude (25). Several investigators have reported reduced birth weight with increasing altitude (26–33). However, because most high-altitude populations are also impoverished (32), the extent to which this reduction is governed by maternal economic status or high altitude remains uncertain.

This study tested the hypothesis that high altitude rather than maternal economic status is associated with reduced and altered fetal growth by comparing the birth weights and body shape at birth of babies in wealthy and impoverished communities in the highest (La Paz, 3649 m above sea level) and lowest (Santa Cruz, 437 m) most populated cities of Bolivia.

Some of these data have been previously presented as an abstract (34).

METHODS

Bolivia.

This South American country is geographically and socioeconomically unique. Whereas the Andean Cordillera runs through the west of the country, eastern parts of the country encompass rain forest regions that span into the Brazilian Amazon. Consequently, Bolivia is divided into several highland (>3500 m above sea level) and lowland (<500 m) regions, which stand highest to lowest as one travels from the west to the east of the country.

The two most populated Bolivian cities, La Paz and Santa Cruz, are also the highest and the lowest in the country, respectively. La Paz is the highest capital city in the world, standing at 3649 m above sea level and containing 1,900,786 inhabitants (35). Santa Cruz stands at 437 m above sea level and has 1,364,389 inhabitants (35). Both La Paz and Santa Cruz are made up of striking economically divergent populations where 71% of the inhabitants in La Paz and 58% of those in Santa Cruz are highly impoverished by standards set by the Bolivian Ministry of Human Development (35). The rest of the populations in La Paz and Santa Cruz maintain a standard of living similar to that in affluent North American or European cities (35).

Maternity hospitals, birth measurements, and maternal characteristics.

Records from pregnancies during 1997 and 1998 were obtained from maternity hospitals situated in wealthy (high-income) and impoverished (low-income) regions of La Paz and Santa Cruz. Informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Ministry for Human Development in Bolivia. Levels of income in families from La Paz and Santa Cruz in the high- and low-income brackets were similar. The average household income in families from the high-income groups was approximately $1500 (US) per month. The average household income in families from the low-income groups was just above the minimal national salary that was 400 bolivianos per month during the period of the study. The high-income maternity hospital in La Paz (high altitude-high income) was CEMES, a private clinic attended selectively by wealthy families. The low-income hospital in La Paz (high altitude-low income) was ENDA Hospital de La Mujer, a government-funded maternity unit situated in the region of El Alto where 90% of the low-income families of La Paz live (35). Similarly, the high-income maternity hospital in Santa Cruz (low altitude-high income) was a branch of PROSALUD, attended by the wealthier families. The low-income maternity hospital in Santa Cruz (low altitude-low income) was SIDCRUZ, a mission hospital that caters specifically to disadvantaged families.

Data describing birth weight, body (crown-heel) length, and head circumference were gathered retrospectively from 100 babies randomly chosen from the available birth books of each of the four hospitals in La Paz and Santa Cruz. All four groups of 100 babies (high altitude-high income, high altitude-low income, low altitude-high income, and low altitude-low income) contained infants born from non-smoking mothers with mixed parity and mixed ages. The level of literacy, professional occupation, and degree of assistance in their own household among the mothers from the high- and low-income groups were very different but similar between La Paz and Santa Cruz. Mothers from the high-income groups, by and large, had finished high school, whereas mothers from the low-income groups had either never attended school or had a level of literacy equivalent to primary school. Mothers from low-income groups were generally domestic helpers with a large degree of assistance in their own household. In contrast, the professional occupation of mothers from high-income groups ranged from company directors to secretarial positions, and these mothers had a comparatively low degree of assistance in their own household. Maternal age at first pregnancy also varied between income groups but was also similar between La Paz and Santa Cruz (La Paz-high income, 22.1 ± 0.5 y; Santa Cruz-high income, 22.8 ± 0.7 y; La Paz-low income, 18.1 ± 0.5 y; Santa Cruz-low income, 18.9 ± 0.9 y; mean ± SEM). In the present study, only singleton pregnancies that reached term (>38 wk) with information about maternal health and smoking were used in the investigation. Other birth records with incomplete information about the mother or the health of the pregnancy were excluded in the analysis.

Data and statistical analyses.

Values for birth weight, body length, head circumference, and head circumference:birth weight ratio are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of any of these variables between La Paz and Santa Cruz and between high- and low-income regions were assessed using ANOVA with the post hoc Dunn's test or the Tukey test, as appropriate. In addition, the cumulative frequency distribution across all birth weights gathered was plotted for each of the groups of babies from La Paz and Santa Cruz. Significance for any statistical comparison was accepted when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Birth measurements.

Mean birth weight was significantly lower in babies from La Paz than in babies from Santa Cruz in both high- and low-income groups (Fig. 1A). Even babies born from impoverished families in the low-income groups of Santa Cruz had considerably greater mean birth weight than babies born from high-income families in La Paz. Babies from low-income families in Santa Cruz had lower mean birth weight than those from high-income families in Santa Cruz. Furthermore, babies from high-income families in La Paz had lower mean birth weight than those from low-income families in La Paz.

Birth weights and measurements in Bolivian babies. Values are mean ± SEM of 100 babies taken from economically divergent populations in La Paz (3649 m above sea level) and Santa Cruz (437 m above sea level). Significant differences are ap < 0.05, La Paz vs Santa Cruz; bp < 0.05, La Paz-high income vs La Paz-low income; cp < 0.05, Santa Cruz-high income vs Santa Cruz-low income; dp < 0.05, Santa Cruz-high income vs all. ANOVA plus Dunn's or Tukey test.

Both low income and altitude were associated with a decrease in body length (Fig. 1B). Head circumference was greater in babies born from high-income families in La Paz than those born from low-income families in La Paz (Fig. 1C). The head circumference:birth weight ratio was greater in babies from La Paz than from Santa Cruz, regardless of income status. In addition, at high altitude but not at low altitude, high income was associated with an increase in the head circumference:birth weight ratio (Fig. 1D).

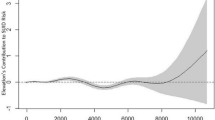

Plots of the cumulative frequency distribution across all birth weights gathered showed a shift to the left in the curve of babies from high altitude compared with from low altitude, regardless of economic status (Fig. 2). The cumulative frequency distribution of babies from La Paz showed that the curve for babies from high-income groups appeared shifted to the left relative to the curve for babies from low-income groups. The cumulative frequency distribution of babies from Santa Cruz showed that the curve for babies from low-income groups appeared shifted to the left relative to the curve of babies from high-income groups (Fig. 2). The percentage of babies with low birth weight was greater in babies from La Paz than those from Santa Cruz in both high- and low-income groups (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

This study used epidemiologic data to test the hypothesis that high altitude rather than maternal economic status is associated with fetal growth retardation and altered fetal growth patterns during gestation in highland regions. Our results support this hypothesis because birth weights in La Paz (high-altitude city) were lower than in Santa Cruz (low-altitude city) in both high- and low-income groups. Interestingly, even babies from the strikingly impoverished low-altitude population of Santa Cruz were heavier than babies from high-income groups of La Paz. Furthermore, the frequency distribution across all birth weights gathered showed a shift to the left in the curve of babies from La Paz compared with babies from Santa Cruz, regardless of maternal economic status. Hence, the percentage of babies with low birth weights was also greater in babies from La Paz than from Santa Cruz in both high- and low-income groups.

The rationale behind this study depends on the assumption that maternal economic status is associated with maternal nutritive state. Although sparse knowledge is available on the contribution of economic status to maternal nutritive state during pregnancy at either low or high altitude, independent studies have reported the unremarkable finding that individuals from low socioeconomic status are under-nourished and that those from high socioeconomic status are well-nourished in Andean countries (36, 37).

The data in the present study support previous findings that reported reduced birth weight at altitude in Colorado (27, 38, 39), Peru (40, 41), and the Himalayas (42, 43). The persistence of low birth weight in babies from La Paz despite this being Bolivia's capital city, coupled with an elevated incidence of reduced birth weight in Colorado reported in other studies (27, 38, 39), lends further support to the hypothesis that high altitude without undernutrition contributes to decreased birth weight in high-altitude populations. Another observation by Howard et al.(44) is of particular significance because it relates to mothers who gave birth to infants with reduced birth weight at the elevated region of Lake County in Colorado but who had previously borne children of normal weight in lowland regions outside of Lake County.

The mechanism mediating a decrease in the rate of fetal growth and altered body shape at birth at high altitude is unclear. Although many factors may distinguish the population of La Paz and Santa Cruz, one possibility is that the hypoxia of pregnancy at altitude may lead to altered fetal growth and reduced birth weight in high-altitude populations. That the highland mother and fetus are hypoxic relative to lowland pregnancies has been determined in previous investigations (25, 32, 45, 46). Furthermore, experiments in pregnant animals echo the contention that chronic hypoxia without undernutrition during pregnancy can lead to growth retardation in utero(47–53).

Additional results in the present study showed that altitude was associated with an increase in the head circumference:birth weight ratio in both high- and low-income groups. Because an increase in this ratio is associated with stroke in adulthood (54), these findings suggest that babies born at high altitude may be more susceptible to this disease. Increased head circumference:body weight ratio may also reflect disproportionate or asymmetric growth retardation that spares brain growth at the expense of the fetal trunk (55). In the human, such fetal adaptations to adverse intrauterine conditions have been suggested to take place if the challenge to the intrauterine environment occurs during the third trimester of gestation (2). Interestingly, Haas et al. (30) reported that the low birth weight measured in Peruvian infants at altitude resulted mainly from reduced adipose deposition and decreased lower limb growth, processes that are known to occur in the last third of gestation in the human. In addition, McCullough et al.(38) and Unger et al.(39) reported that the greatest reduction in fetal growth rate in human pregnancies in Colorado occurred after 32 wk of gestation. Thus, it can be inferred from past and present observations that fetal growth retardation at high altitude may occur primarily in late gestation and may reflect maternoplacental insufficiency to meet the fetal oxygen demands at this time. Potential mechanisms may include a reduction in the transplacental oxygen partial pressure gradient (56) and/or depressed uteroplacental vasodilators (57, 58) leading to reduced uterine blood flow (32, 59), all of which have been reported in high-altitude pregnancy. It is possible that this unmatched fetal oxygen demand may trigger the release of fetoplacental hormones and factors that control tissue accretion and differentiation in the fetus during late gestation, such as insulin, thyroxine, cortisol, and IGF (60, 61). Pregnancy at high altitude may also alter the fetal plasma concentrations of binding proteins and the sensitivity of fetal tissues to these hormones and/or factors. The sparse available data suggest that up-regulation of IGF-binding proteins by chronic hypoxia may provide a mechanism operating in the human fetus to restrict IGF-mediated growth in utero(62, 63). In addition, human fetal growth may be regulated directly by the availability of oxygen. Hence, a direct effect of reduced oxygen tension on mitotic rate cannot be ruled out (43, 64).

Of further interest are the findings of the present study that show a greater incidence of reduced birth weights across all ranges of birth weights gathered in babies from high-income compared with low-income groups in La Paz. In addition, at high altitude but not at low altitude, high income was associated with an increase in the head circumference:birth weight ratio This is reminiscent of the more complete observations of Zamudio et al. (43) and Haas et al. (65) who suggested that fetal growth retardation at altitude is correlated to the duration of high-altitude residence, independent of maternal nutrition: the longest resident population experiencing the least decline and the shortest resident groups demonstrating the most reduction in birth weight. Accordingly, reductions in birth weight at elevations greater than 3000 m above sea level are greatest in North Americans, intermediate in South Americans, and least in Tibetans (43). Thus, women from high-altitude resident ancestry like the Tibetans (43) and the Aymaras (65) give birth to heavier babies than women from low-altitude resident ancestry like Han women in China and women from European or mestizo ancestry in South America. In the present study, the low socioeconomic group of La Paz contained a high percentage (92%) of women from Amerindian origin with Aymara patronymics and matronymics (32). In contrast, the high socioeconomic group of La Paz contained a high European admixture (62%). In addition, the attenuated increase in head circumference:body weight ratio in babies from low-income groups compared with those from high income in La Paz in the present study may represent a reduced drive to redistribute the fetal cardiac output toward the brain away from the peripheral circulations in Aymaran fetuses. These observations provide some evidence in support of the presence of protective mechanisms against altitude-associated fetal growth retardation in Bolivians from prolonged high-altitude resident ancestry. The physiology behind this protection and whether these mechanisms are at the maternal and/or placental and/or fetal level remain unknown. However, recently Beall et al.(66) identified a major gene that enhances arterial oxygen saturation in sedentary Tibetan natives. Moore (67) suggested that uterine blood flow was greater in Tibetan women than in acclimatized Han newcomers during pregnancy. Other studies have shown that the placenta at high altitude is more vascularized and has a greater diffusion capacity than at low altitude (68, 69).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that high altitude, independent of maternal economic status, is associated with low birth weight and altered body shape at birth in babies from highland regions of Bolivia.

References

Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ 1989 Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 2: 577–580

Barker DJP 1998 Mothers, Babies, and Disease in Later Life. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Rich-Edwards JW, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Hennekens CH 1997 Birth weight and risk of cardiovascular disease in a cohort of women followed up since 1976. BMJ 315: 396–400

Leon DA, Lithell HO, Vagero D, Koupilova I, Mohsen R, Berglund L, Lithell UB, McKeigue PM 1998 Reduced fetal growth rate and increased risk of death from ischaemic heart disease: cohort study of 15000 Swedish men and women born 1915–29. BMJ 317: 241–245

Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Winter PD, Osmond C, Barker DJ 1999 Catch-up growth in childhood and death from coronary heart disease: longitudinal study. BMJ 318: 427–431

Law CM, Shiell AW 1996 Is blood pressure inversely related to birth weight? The strength of evidence from a systematic review of the literature. J Hypertens 14: 935–941

Kolacek S, Kapetanovic T, Luzar V 1993 Early determinants of cardiovascular risk factors in adults. Acta Peadiatr 82: 377–382

Stein CE, Fall CH, Kumaran K, Osmond C, Cox V, Barker DJ 1996 Fetal growth and coronary heart disease in south India. Lancet 348: 1269–1273

Penrose LS 1954 Some recent trends in human genetics. Cardiologia 6( suppl): 521–529

Morton NE 1955 The inheritance of human birthweight. Ann Hum Genet 20: 123–134

Walton A, Hammond J 1938 Proc R Soc Lond B Biol S. ci 125: 311–335.

Wilson ME, Biensen NJ, Youngs CR, Ford SP 1998 Development of Meishan and Yorkshire littermate conceptuses in either a Meishan or Yorkshire uterine environment to day 90 of gestation and to term. Biol Reprod 58: 905–910

Giussani DA, Forhead AJ, Allen WR, Fowden AL 1999 Fetal overgrowth influences postnatal regulation of arterial blood pressure in the horse. J Soc Gynecol Invest 6( 1), 171A ( abstr)

Barker DJ 1995 Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 311: 171–174

Gluckman P, Harding J 1992 The regulation of fetal growth. In: Hernandez M, Argente J (eds) Human Growth: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 253–259.

Godfrey KM 1998 Maternal regulation of fetal development and health in adult life. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 78: 141–150

Lechtig A, Yarbrough C, Delgado H, Habicht JP, Martorell R, Klein RE 1975 Influence of maternal nutrition on birth weight. Am J Clin Nutr 28: 1223–1233

Mora JO, de Paredes B, Wagner M, de Navarro L, Suescun J, Christiansen N, Herrera MG 1979 Nutritional supplementation and the outcome of pregnancy. I. Birth weight. Am J Clin Nutr 32: 455–462

Frisancho AR, Klayman JE, Matos J 1977 Influence of maternal nutritional status on prenatal growth of a Peruvian urban population. Am J Phys Anthropol 46: 265–274

Langley-Evans SC, Gardner DS, Welham SJM 1998 Intrauterine programming of cardiovascular disease by maternal nutritional status. Nutrition 14: 39–47

Woodall SM, Johnston BM, Breier BH, Gluckman PD 1996 Chronic maternal undernutrition in the rat leads to delayed postnatal growth and elevated blood pressure of offspring. Pediatr Res 40: 438–443

Anderson GD, Ahokas RA, Lipshitz J, Dilts PV 1980 Effect of maternal dietary restriction during pregnancy on maternal weight gain and fetal birth weight in the rat. J Nutr 110: 883–890

Harding JE, Johnston BM 1995 Nutrition and fetal growth. Reprod Fertil Dev 7: 539–547

Robinson JS, Owens JA, Owens PC 1994 Fetal growth and fetal growth retardation. In: Thorburn GD, Harding R (eds) Textbook of Fetal Physiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 83–94.

Moore LG, Niermeyer S, Zamudio S 1998 Human adaptation to high altitude: regional and life-cycle perspectives. Am J Phys Anthropol 27( suppl): 25–64

McClung J 1969 Effects of High Altitude on Human Birth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Lichty JA, Ting RY, Bruns P, Dyer E 1957 Studies of babies born at high altitude. 1. Relation of altitude to birth weight. Am J Dis Child 93: 666–669

Sobrevilla LA, Nacer en los Andes 1971 Estudios fisiologicos sobre el embarazo y parto en la altura. Doctoral thesis, Universidad Peruana Cayetona Heredia, Instituto de Investigaciones de la Altura, Lima, Peru

Yip R 1987 Altitude and birth weight. J Pediatr 111: 869–876

Haas JD, Baker PT, Hunt EE 1977 The effects of high altitude on body size and composition of the newborn infant in southern Peru. Hum Biol 49: 611–628

Ballew C, Haas JD 1986 Altitude differences in body composition among Bolivian newborns. Hum Biol 58: 871–882

Niermeyer S, Zamudio S, Moore LG The people. In: Hornbein T, Schoene RS, D Dekker (eds) High Altitude. ( in press)

Beall CM 1976 The effects of high altitude on growth, morbidity, and mortality of Peruvian infants. Ph.D. dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA

Giussani DA, Barker DJP 1999 Bolivia and the Barker hypothesis. J Soc Gynecol Invest 6( suppl 1): 106A( abstr)

Mapa de pobreza 1995 Una guía para la acción social, 2nd Ed. Ministerio de desarrollo humano, República de Bolivia, La Paz

Tellez W, Sam-Miguel JL, Rodriguez A, Chavez M, Lujan C, Quintela A 1994 Circulating proteins and iron status in blood as indicators of the nutritional status of 10- to 12-year-old Bolivian boys. Int J Sports Med 15( suppl 2): S79–S83

Post GB, Lujan C, San-Miguel JL, Kemper HC 1994 The nutritional intake of Bolivian boys. The relation between altitude and socioeconomic status. Int J Sports Med 15( suppl 2): S100–S105

McCullough RE, Reeves JT, Liljegren RL 1977 Fetal growth retardation and increased infant mortality at high altitude. Obstet Gynecol Surv 32: 596–598

Unger C, Weiser JK, McCullough RE, Keefer S, Moore LG 1988 Altitude, low birth weight, and infant mortality in Colorado. JAMA 259: 3427–3432

Pan American Health Organization 1994 Health Conditions in the Americas. Scientific Publication No. 549. World Health Organization, Washington DC

Gonzales GF, Guerra-Gracia R 1993 Características hormonales y antropométricas del embarazo y del recien nacido en la altura. In: Gonzales GF (ed) Reproducción Humana en la Altura. Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Lima, Peru, pp 125–141.

Wiley AS 1993 Neonatal size and infant mortality at high altitude in the western Himalaya. Am J Phys Anthropol 94: 289–305

Zamudio S, Droma T, Norkyel KY, Acharya G, Zamudio JA, Nirmeyer SN, Moore LG 1993 Protection from intrauterine growth retardation in Tibetans at high altitude. Am J Phys Anthropol 91: 215–224

Howard RC, Lichty JA, Bruns PD 1957 Measurement of birth weight, body length, and head size. Am J Dis Child 93: 670–678

Ballew C, Haas JD 1986 Hematologic evidence of fetal hypoxia among newborn infants at high altitude in Bolivia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 155: 166–169

Sobrevilla LA, Cassinelli MT, Carcelen A, Malaga JM 1971 Human fetal and maternal oxygen tension and acid-base status during delivery at high altitude. Am J Obstet Gynecol 111: 1111–1118

Van Geijn HP, Kaylor WM, Nicola KR, Zuspan FP 1981 Intrauterine growth retardation by lowered ambient oxygen concentration. In: Van Assche FA, Robertson WB (eds) Fetal Growth Retardation. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 231–241.

Chang JHT, Rutledge JC, Stoops D, Abbe R 1984 Hypobaric hypoxia-induced intrauterine growth retardation. Biol Neonate 46: 10–13

Garvey DJ, Longo LD 1978 Chronic low-level maternal carbon monoxide exposure and fetal growth development. Biol Reprod 19: 8–14

Gilbert RD, Cummings LA, Juchau MR, Longo LD 1979 Placental diffusing capacity and fetal development in exercise or hypoxic guinea pig. J Appl Physiol 46: 828–834

Hebbe RP, Berger EM, Eaton JW 1980 Effect of increased maternal hemoglobin oxygen affinity on fetal growth in the rat. Blood 55: 969–974

De Grauw TJ, Myers R, Scott WJ 1986 Fetal growth in rats from different levels of hypoxia. Biol Neonate 49: 85–89

Jacobs R, Robinson JS, Owens JA, Falconer J, Webster MED 1988 The effect of prolonged hypobaric hypoxia on growth of fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol 10: 97–112

Martyn CN, Barker DJP, Osmond C 1996 Mother's pelvic size, fetal growth, and death from stroke and coronary heart disease in men in the UK. Lancet 348: 1264–1268

Clapp JF 1996 The clinical significance of asymmetric intrauterine growth retardation. Pediatr Ann 25: 223–227

Makowski EL, Battaglia FC, Meschia G, Behrman RE, Schruefer J, Seeds AE, Bruns PD 1968 Effect of maternal exposure to high altitude upon fetal oxygenation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 100: 852–861

Sobrevilla LA, Romero I, Kruger F 1971 Estriol levels of cord blood, maternal venous blood, and amniotic fluid at delivery at high altitude. Am J Obstet Gynecol 110: 596–597

Zamudio S, Leslie K, White M, Hagerman D, Moore LG 1994 Low serum estradiol and high serum progesterone concentrations characterize hypertensive pregnancies at high altitude. J Soc Gynecol Invest 1: 197–205

Zamudio S, Palmer SK, Droma T, Stamm E, Coffin C, Moore L 1995 Effect of altitude on uterine artery blood flow during normal pregnancy. J Appl Physiol 79: 7–14

Gluckman PD 1986 The role of pituitary hormones, growth factors, and insulin in the regulation of fetal growth. Oxf Rev Reprod Biol 8: 1–60

Fowden AL 1995 Endocrine regulation of fetal growth. Reprod Fertil Dev 7: 315–363

Tazuke SI, Mazure NM, Sugawara J, Carland G, Faessen GH, Suen LF, Irwin JC, Powell DR, Giaccia AJ, Giudice LC 1998 Hypoxia stimulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) gene expression in HepG2 cells: a possible model for IGFBP-1 expression in fetal hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 10188–10193

Tapanainen PJ, Bang P, Wilson K, Unterman TG, Vreman HJ, Rosenfeld RG 1994 Maternal hypoxia as a model for intrauterine growth retardation: effects on insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins. Pediatr Res 36: 152–158

Malaspina L, Quilici JC, Ergueta Collao J 1971 Modificaciones de las condiciones del cultivo celular en la altura. Ann Inst Boliviano Biol Altura 2: 3–5

Haas JD, Frongillo EF, Stepcik C, Beard J, Hurtado L 1980 Altitude, ethnic, and sex differences in birthweight and length in Bolivia. Hum Biol 52: 459–477

Beall CM, Blangero J, William-Blangero S, Goldstein MC 1994 Major gene for percent of oxygen saturation of arterial hemoglobin in Tibetan highlanders. Am J Phys Anthropol 95: 271–276

Moore LG 1990 Maternal O2 transport and fetal growth in Colorado, Peru, and Tibet high-altitude residents. Am J Hum Biol 2: 627–637

Reshetnikova OS, Burton GJ, Milovanov AP 1994 Effects of hypobaric hypoxia on the fetoplacental unit: the morphometric diffusing capacity of the villous membrane at high altitude. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171: 1560–1565

Mayhew TM, Jackson MR, Haas JD 1990 Oxygen diffusive conductances of human placentae from term pregnancies at low and high altitudes. Placenta 11: 493–503

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ministry for Human Development in Bolivia, Dr. Liselotte Barragan, Professor Carlos Blanco, and Bruno Giussani for their invaluable help with this research and the production of this manuscript. We also thank Margaret Bardy for her help with the references.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by The Department of Physiology at Cambridge University and the MRC Environmental Epidemiology Unit at Southampton University.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giussani, D., Phillips, P., Anstee, S. et al. Effects of Altitude versus Economic Status on Birth Weight and Body Shape at Birth. Pediatr Res 49, 490–494 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200104000-00009

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200104000-00009

This article is cited by

-

Influence of geographic conditions on body length of male newborns in Kyrgyzstan

International Journal of Biometeorology (2021)

-

High Altitude Continues to Reduce Birth Weights in Colorado

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2019)

-

Prenatal hypoxia leads to hypertension, renal renin-angiotensin system activation and exacerbates salt-induced pathology in a sex-specific manner

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Forced Marriage and Birth Outcomes

Demography (2017)

-

Renal developmental defects resulting from in utero hypoxia are associated with suppression of ureteric β-catenin signaling

Kidney International (2015)