Abstract

Neutrophils from patients suffering from glycogen storage disease type Ib (GSD-Ib) show several defects, one of which is a decreased rate of glucose utilization. In this study, we established experimental conditions to show the stimulation of the neutrophil respiratory burst by extracellular glucose. With phorbol-myristate-acetate as stimulus of the burst, the activity of the NADPH oxidase in GSD-Ib neutrophils hardly increased on addition of glucose. In control and GSD-type Ia neutrophils, a clear increase was observed. The lack of response to extracellular glucose in GSD-Ib neutrophils is correlated with the inability to raise intracellular glucose-6-P levels on glucose addition, thereby limiting the activity of the generation of NADPH in the hexose-monophosphate shunt. Our study shows the usefulness of this test for the diagnosis of neutrophil function abnormality in GSD-Ib patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

GSD-1 is caused by an insufficient activity of glucose-6-phosphatase in the liver. The model commonly used to describe glucose-6-phosphatase activity predicts that glucose-6-phosphatase is a multicomponent complex, consisting of a catalytic unit and several transporters(1,2). According to this transport model biochemically different subtypes of GSD-I can be distinguished: called GSD-Ia, GSD-Ib, GSD-Ic, and GSD-Id. It has been known for many years that neutrophils from patients suffering from GSD-Ib show marked functional deficiencies in several in vitro tests. Decreased responses have been reported for neutrophil chemotaxis(3,4), elevation of cytosolic free Ca2+(5), and rate of glucose transport(6,7). Moreover, GSD-1b patients often show mild to severe neutropenia. Because neutrophils play an important role in the host defense against invading microorganisms, these patients are at high risk to encounter life-threatening infections. Treatment with G-CSF has been shown to have a beneficial effect on the clinical status of these patients(8,9).

Until now, it has not been clarified why the neutrophils of GSD-Ib patients show impaired responses. It has been established that in liver microsomes, freshly prepared from liver biopsies of GSD-Ib patients, the hydrolysis of G6P is impaired(10). This defect is alleviated on detergent addition, which has led to the suggestion that G6P transport across the endoplasmatic reticulum membrane is disturbed in GSD-Ib patients(1,11).

In liver microsomes of patients with GSD-Ia, G6P hydrolysis is also absent, but these patients show a defect in the enzyme catalyzing G6P hydrolysis. In contrast to GSD-Ib and probably GSD-Ic, the neutrophils of GSD-Ia patients show no abnormalities.

The cDNA encoding human liver glucose-6-phosphatase has been cloned(12) and several mutations responsible for GSD-Ia have since then been identified(13,14). By homozygosity mapping the gene causing GSD-Ib and GSD-Ic has been located to chromosome 11q23(15,16). Moreover, Gerin et al.(17) recently identified a gene encoding a putative G6P translocase(17) that contained mutations in two GSD-Ib patients. Although detailed analysis of the genes involved will help future classification of patients, information regarding neutrophil function will still be useful for diagnostic and treatment purposes.

Although neutrophils can readily be obtained from peripheral blood, only small numbers can be isolated from GSD-Ib patients and function tests are often laborious and sensitive to many influences. We therefore developed a convenient test to investigate neutrophil function, which might aid in diagnosing patients suspected of GSD-Ib.

In our study, we investigated in detail the dependence of the respiratory burst (catalyzed by the NADPH oxidase) on extracellular glucose and the relationship between intracellular G6P levels and oxidase activity. The results show an aberrant relationship between extracellular glucose and intracellular G6P in GSD-1b neutrophils, which can be used for a reliable characterization of these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients. Blood of children (aged 4-12 yr) with GSD-I was obtained after informed consent of the parents. These patients were hospitalized in one of the three pediatric clinics participating in this study (Groningen, Utrecht, Warsaw, Poland). Diagnosis in all patients was confirmed by enzymological studies in fresh liver biopsies(1). None of the patients had ever been treated with G-CSF at the time the experiments were carried out. This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Hospital Groningen.

Isolation of neutrophils. Heparized blood (10 mL) samples were obtained from healthy volunteers, GSD-Ia patients or from GSD-Ib patients, and kept at room temperature during transport to the laboratory (lasting 2-12 h). Control blood samples from healthy volunteers were kept at room temperature for a similar time period. In some experiments, human cord blood was used (see text). In the laboratory, the blood samples were diluted 2-fold with PBS containing 0.4% (w/v) trisodium citrate (pH 7.4) and layered onto isotonic Percoll with a specific gravity of 1.076 g/mL. After centrifugation (20 min, 1800 × g), the interphase containing the mononuclear cells was removed. The pellet fraction, containing erythrocytes and granulocytes, was treated for 10 min with ice-cold isotonic NH4Cl solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) to lyse the erythrocytes. The remaining granulocytes were washed once in NH4Cl lysis buffer and twice with PBS before resuspension in incubation medium containing 132 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, and 0.5% (w/v) human serum albumin (pH 7.4). The granulocytes had a purity of more than 98%, and consisted mainly of neutrophils (>95%).

Measurement of oxygen consumption in purified neutrophils. Activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst was measured in a closed oxygraph vessel, equipped with an oxygen electrode and thermostated at 37°C. Neutrophils (2 × 106/mL) were preincubated for 10 min and then stimulated with PMA (100 ng/mL) that was added with a Hamilton syringe from a concentrated stock (100 mg/mL) in DMSO. After 3-4 min of activation in the absence of glucose, glucose (5 mM) was added from a stock solution (0.5 M) in PBS. Rates of oxygen uptake in the absence and presence of glucose were calculated from the linear parts of the oxygen consumption curve 2 min before and 2 min after the addition of glucose and were corrected for the rate of oxygen consumption before stimulation (amounting to 0.3-0.4 nmol O2/min per 106cells).

Measurement of superoxide anion production. The production of superoxide anion (O2-) by neutrophils was measured with the ferricytochrome c reduction assay(18). Neutrophils (5 × 105/mL) were incubated under the same conditions as described above, but with 60 µM of ferricytochrome c (from horse heart, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and presence of 2 mM azide. Two cuvettes (0.8 mL) were put in a thermostated cuvette holder of a double-beam spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer lambda 6), equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The reference cuvette contained SOD (75 U/mL). Activation of the cells and addition of glucose was carried out as described above for the oxygraph experiments.

Measurement of intracellular G6P and ATP levels. For determination of intracellular G6P, purified human neutrophils (2 × 107/mL) were incubated for 10 min at 37°C in an incubation medium in the absence or presence of glucose (5 mM). Subsequently, 500 µL cell suspension were deproteinized with 125 µL of perchloric acid (14%, w/v). After 10 min on ice, the sample was centrifuged at 4°C (12.000 × g, 10 min) and 500 µL of the protein-free supernatant was neutralized with 2 M KOH/0.2 M MOPS. Samples were stored at -80°C. After thawing, samples were cleared by centrifugation (12.000 × g, 10 min) and G6P was determined in a fluorimetric assay following the reduction of NADP+ to NADPH by G6P-dehydrogenase from yeast (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) as previously described(19). The lower limit of sensitivity of this assay (defined as twice the signal of an enzyme control addition) was estimated to be 20 pmol/106 cells. After complete conversion of the G6P present in each sample and adjustment of the sensitivity of the spectrofluorimeter (model RF-540, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), hexokinase (Boehringer Mannheim) and glucose (10 mM) was added to determine the ATP content of each sample(19). Control experiments (not shown) in which the neutrophils were centrifuged through a layer of phtalate oil, indicated that 95% of the G6P and ATP were intracellular, concurrent with a release of 5% of lactate dehydrogenase as indicator of cell damage.

RESULTS

Maintenance of NADPH oxidase activity in activated neutrophils requires the generation of NADPH by G6P-dehydrogenase and for this reaction cytosolic G6P needs to be synthesized from intra- or extracellular glucose. When neutrophils of control donors or GSD-Ib patients were stimulated with PMA in the absence of extracellular glucose, the respiratory burst was activated as indicated by a sharp increase in the of oxygen consumption (Fig. 1). A constant rate of oxygen consumption was reached after a lag-time of 30 to 60 s. In control neutrophils the activity of the NADPH oxidase was enhanced nearly 2-fold on addition of glucose (Fig. 1, lower trace). Hence, under these experimental conditions, maximal activity of the NADPH oxidase depends on the influx of glucose across the plasma membrane. However, when the same experiment was carried out with neutrophils from GSD-Ib patients, the response to extracellular glucose was virtually absent (Fig. 1, upper trace).

Oxygen uptake in control and GSD-1b neutrophils: effect of extracellular glucose. Neutrophils (2.106/mL) from a control donor (lower trace, black line) and a GSD-1b patient (upper trace, dashed line) were incubated in an oxygraph as described in "Materials and Methods." The figure represents a direct recording in time of the oxygen concentration in the oxygraph vessel. At the first arrow (P), PMA (100 ng/mL) was added to activate the respiratory burst, at the second arrow (G) glucose (5 mM) was added. The dotted line indicates the result obtained when glucose was not added to the incubation. Similar defects in responses to glucose addition in the GSD-1b neutrophils as shown were observed in five other patients.

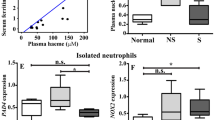

The activities measured in the experimental set-up of Figure 1 can be made independent of the variation in oxidase activity between different neutrophil preparations, by dividing the activity observed in the presence of glucose by that observed in the absence of glucose. The activity ratio thus obtained was markedly lower in six different GSD-Ib patients compared with that of controls (Table 1). In contrast, the neutrophils from five GSD-Ia patients showed a response to glucose that was slightly higher than that of control neutrophils (Table 1). In addition, neutrophils of neonates isolated from human cord blood also showed a normal stimulation by glucose of the PMA-induced respiratory burst (Table 1).

In the experiments as depicted in Figure 1, oxygen consumption (measured with an oxygen electrode) was used to determine respiratory burst activity. Measurement of superoxide generation, as measured by the SOD-sensitive reduction of cytochrome c(18), is a more convenient way for most laboratories to detect respiratory burst activation. However, in this latter assay only a part of the PMA-induced oxidase activity is detected(20). Nevertheless, the addition of glucose caused a 2-fold enhancement of PMA-induced superoxide production in control neutrophils, but not in GSD-1b neutrophils (Fig. 2).

Superoxide production in control and GSD-1b neutrophils: effect of extracellular glucose. Neutrophils (5.105/mL) from a control donor (upper trace) and a GSD-1b patient (lower trace) were incubated at 37°C and cytochrome c reduction was continuously recorded in time as described in "Materials and Methods." At the first arrow, PMA (100 ng/mL) was added to activate the respiratory burst, at the second arrow glucose (5 mM) was added.

The most likely explanation for the enhancement of respiratory burst activity by extracellular glucose is that the addition of glucose results in an enhancement of the rate of NADPH generation by increasing the intracellular concentration of G6P. To test the validity of this hypothesis, we measured in control and patient neutrophils the concentration of intracellular G6P in the absence and presence of extracellular glucose. Indeed, in control neutrophils the intracellular level of G6P was about 5-fold higher in the presence of extracellular glucose (Table 2). In the neutrophils of three different GSD-Ib patients, the intracellular level of G6P only marginally increased in the presence of extracellular glucose and was, in fact, quite similar to that of control neutrophils incubated in the absence of glucose (Table 2). The ATP levels in control and GSD-Ib neutrophils were not significantly different (Table 2), excluding a limitation of burst activity by intracellular ATP. The level of G6P in the neutrophils of two GSD-Ia patients increased in response to extracellular glucose in a similar way as control neutrophils (data not shown). Apparently, extracellular glucose greatly influences the G6P concentration in control and GSD-Ia neutrophils, but not in GSD-Ib neutrophils.

The results shown in Table 2 suggest that G6P levels can be limiting for NADPH oxidase activity at the onset of PMA stimulation. In the experiments depicted in Figure 3, we also measured G6P levels in control neutrophils after PMA stimulation. In the presence of extracellular glucose, the G6P concentration after PMA stimulation was always higher than in the absence of glucose, although in the latter condition the G6P concentration did increase in response to PMA. Because this type of analysis requires an appreciable number of cells, kinetics of G6P changes could not be measured in GSD-Ib neutrophils.

G6P levels in control after stimulation with PMA. Neutrophils (107/mL) were incubated in incubation medium in the absence (open symbols) or presence of 5 mM glucose (closed symbols) for 10 min at 37°C. Subsequently, PMA (100 ng/mL) was added and, at the times indicated, 0.5 mL of each incubation was quenched with perchloric acid, neutralized, and stored for fluorimetric analysis of G6P as described in "Materials and Methods." Results shown are the mean ± SEM of three different experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that in normal neutrophils the activity of the NADPH oxidase is partially dependent on extracellular glucose. This can most readily be observed by glucose addition to neutrophils prestimulated with PMA (Fig. 1). Interestingly, addition of glucose to PMA- stimulated GSD-Ib neutrophils did not result in stimulation of NADPH oxidase activity. This procedure (measuring the ratio of activities in the absence and presence of glucose minimizing the variation in neutrophil activities observed between different donors) discriminates very well between GSD-Ib neutrophils and GSD-Ia neutrophils (Table 1)

The stimulation by glucose of the NADPH oxidase is most likely due to elevation of intracellular G6P concentration, allowing a greater flux through the hexose-monophosphate shunt with concomitant NADPH production. In support of this notion, G6P levels in control, but not GSD-Ib neutrophils, increased on addition of glucose (Table 2). Decreased flux through the hexose-monophosphate shunt in GSD-Ib neutrophils has been documented before(7). It has been shown that PMA activation of neutrophils does induce the breakdown of glycogen(21), but apparently the rate of intracellular mobilization of glucose is not sufficient to compensate for G6P consumption under these conditions of activation (Fig. 3).

The stimulation of the respiratory burst in neutrophils by extracellular glucose is not only observed with PMA as activator (Fig. 1), but also after activation with serum-treated zymosan (STZ, data not shown) or formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP)(5). For the detection of GSD-1b neutrophils the two latter stimuli have serious drawbacks for the following reasons. Neutrophils of children of very young age express lower levels of complement receptor type 3(22), limiting the binding of the iC3b-coated STZ particles to the cells(23). Neutrophils isolated from neonates showed essentially the same stimulation by glucose of the PMA-induced burst as neutrophils from healthy adults (Table 1), although stimulation by chemotactic agonists of glucose transport has been reported to be abnormal in these cells(24). The use of fMLP as activator in these kinds of studies(5,25) is questionable, because the burst activity induced by this agonist is very sensitive to cytokines or other priming factors(26), that could be variable among different patients. We would therefore argue that the glucose stimulation of a PMA-induced burst is most suitable for the diagnosis of GSD-Ib, also in children of very young age.

A simplified version of the test described in Figure 2 is a discontinuous measurement of SOD-sensitive cytochrome c reduction allowing measurements to be carried out on a simple spectrophotometer in cell-free supernatants after centrifugation of the cells. However, in this set-up the cells need to be incubated under a variety of conditions (± PMA, ± glucose, ± SOD) to allow proper assessment of SOD-sensitive cytochrome c reduction. The most important caveat in this latter procedure is to use limited incubation periods in the presence of PMA and low cell numbers to avoid exhaustion of the cytochrome c added. Also, in this set-up the dependence of the PMA-induced respiratory burst on extracellular glucose could be demonstrated (data not shown).

We recently described a patient with GSD-Ic, characterized by a defect in a putative phosphate/pyrophosphate carrier(27). Neutrophils of this patient showed the same inability to use extracellular glucose as neutrophils of the above described patients with GSD-Ib. Now that the same mutations have been found in GSD-Ib and GSD-Ic(28), one has to consider the possibility that G6P and phosphate are transported by the same protein.

The underlying mechanism of the inability of glucose to stimulate PMA-induced oxidase activity in GSD-Ib neutrophils (Fig. 1, Table 1) is, as yet, unclear. We hypothesize that this defect is due to the observed aberration in Ca2+ homeostasis in GSD-Ib neutrophils(5) (Verhoeven AJ, unpublished experiments). The latter defect might directly be linked to the established deficiency in GSD-Ib liver microsomes to transport G6P, because uptake of Ca2+ into the lumen of the endoplasmatic reticulum is greatly enhanced by G6P(29,30). Neutrophils might contain glucose transporters within their numerous intracellular vesicles and granules that could be up-regulated during isolation or on appropriate stimulation in a manner similar to the up-regulation of adhesion proteins and receptors(31). Changes in cytosolic-free Ca2+ have been shown to be essential for up-regulation of intracellular membrane antigens(32,33). It should be mentioned that these considerations do not explain the results of Potashnik et al.(6), who have suggested that in GSD-Ib neutrophils the rate of glucose phosphorylation rather than the rate of transport is impaired. Surprisingly, little is known concerning type and location of glucose transporters in human neutrophils. Further studies on this topic might shed light on the neutrophil defects observed in GSD-Ib patients.

Abbreviations

- GSD-Ia:

-

glycogen storage disease type Ia

- GSD-Ib:

-

glycogen storage disease type Ib

- G-CSF:

-

granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- G6P:

-

glucose-6-phosphate

- HEPES:

-

hydroxy-ethyl-piperazine-ethane-sulfonic acid

- PMA:

-

phorbol-myristate-acetate

- DMSO:

-

dimethylsulfoxide

- MOPS:

-

morpholino-propane-sulfonic acid

- STZ:

-

serum-treated zymosan

- fMLP:

-

formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- SOD:

-

superoxide dismutase

- PBS:

-

phosphate-buffered saline

References

Burchell A 1990 Molecular pathology of glucose-6-phosphatase. FASEB J 4: 2978–2988.

Arion WJ, Canfield WK, Callaway ES, Burger HJ, Hemmerle H, Schubert G, Herling AW, Oekonomopulos R 1998 Direct evidence for the involvement of two glucose 6-phosphate-binding sites in the glucose-6-phosphatase activity of intact liver microsomes-characterization of T1, the microsomal glucose 6-phosphate transport protein by a direct binding assay. J Biol Chem 273: 6223–6227.

Beaudet AL, Anderson DC, Michels VV, Arion WJ, Lange AJ 1980 Neutropenia and impaired neutrophil migration in type IB glycogen storage disease. J Pediatr 97: 906–910.

Koven NL, Clark MM, Cody CS, Stanley CA, Baker L, Douglas SD 1996 Impaired chemotaxis and neutrophil (polymorphonuclear leukocyte) function in glycogenosis type IB. Pediatr Res 20: 438–442.

Kilpatrick L, Garty BZ, Lundquist KF, Hunter K, Stanley CA, Baker L, Douglas SD, Korchak HM 1990 Impaired metabolic function and signaling defects in phagocytic cells in glycogen storage disease type 1b. J Clin Invest 86: 196–202.

Potashnik R, Moran A, Moses SW, Peleg N, Bashan N 1990 Hexose uptake and transport in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with glycogen storage disease Ib. Pediatr Res 28: 19–23.

Bashan N, Hagai Y, Potashnik R, Moses SW 1988 Impaired carbohydrate metabolism of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in glycogen storage disease Ib. J Clin Invest 81: 1317–1322.

Roe TF, Coates TD, Thomas DW, Miller JH, Gilsanz V 1992 Brief report: treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel disease in glycogen storage disease type Ib with colony-stimulating factors. N Engl J Med 326: 1666–1669.

Lachaux A, Boillot O, Stamm D, Canterino I, Dumontet C, Regnier F, Floret D, Hermier M 1993 Treatment with lenograstim (glycosylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) and orthotopic liver transplantation for glycogen storage disease type Ib. J Pediatr 123: 1005–1008.

Igarashi Y, Kato S, Narisawa K, Tada K, Amano Y, Mori T, Takauchis S 1984 A direct evidence for defect in glucose-6-phosphatase transport system in hepatic microsomal membrane of glycogen storage disease type IB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 119: 593–597.

Nordlie RC, Sukalski KA 1986 Multiple forms of type I glycogen storage diease: underlying mechanisms. TIBS 11: 85–88.

Lei KJ, Shelly LL, Pan CJ, Sidbury JB, Chou JY 1993 Mutations in the glucose-6-phosphatase gene that cause glycogen storage disease type 1a. Science 262: 580–583.

Parvari R, Lei KJ, Bashan N, Hershkovitz E, Korman SH, Barash V, Lerman-Sagie T, Mandel H, Chou JY, Moses SW 1997 Glycogen storage disease type 1a in Israel: biochemical, clinical, and mutational studies. Am J Med Genet 72: 286–290.

Parvari R, Lei KJ, Szonyi L, Narkis G, Moses S, Chou JY 1997 Two new mutations in the glucose-6-phosphatase gene cause glycogen storage disease in Hungarian patients. Eur J Hum Genet 5: 191–195.

Annabi B, Hiraiwa H, Mansfield BC, Lei KJ, Ubaiga T, Polymeropoulos MH, Moses SW 1998 The gene for glycogen storage disease type Ib maps to 11q23. Am J Hum Genet 62: 400–405.

Fenske CD, Jeffery S, Weber JL, Houlston RS, Leonard JV, Lee PJ 1998 Localisation of the gene for glycogen storage disease type 1c by homozygosity mapping to 11q. J Med Genet 35: 269–272.

Gerin I, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Achouri Y, Collet JF, Van Schaftingen E 1997 Sequence of a putative glucose 6-phosphate translocase, mutated in glycogen storage disease type Ib. FEBS Lett 419: 235–238.

Babior BM, Kipnes RS, Curnutte JT 1973 Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest 52: 741–744.

Verhoeven AJ, Kamer P, Groen AK, Tager JM 1985 Effects of thyroid hormone on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Biochem J 226: 183–192.

Lundqvist H, Follin P, Khalfan L, Dahlgren C 1996 Phorbol myristate acetate-induced NADPH oxidase activity in human neutrophils: only half the story has been told. J Leukoc Biol 59: 270–279.

Borregaard N, Juhl H 1981 Activation of the glycogenolytic cascade in human polymorphonuclear leucocytes by different phagocytic stimuli. Eur J Clin Invest 11: 257–263.

Abughali N, Berger M, Tosi MF 1994 Deficient total cell content of CR3 (CD11b) in neonatal neutrophils. Blood 83: 1086–1092.

Wright SD, Meyer BC 1986 Phorbol ester cause sequential activation and deactivation of complement receptors on polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Immunol 136: 1759–1764.

Abughali N, Dubyak G, Tosi MF 1993 Impairment of chemoattractant-stimulated hexose uptake in neonatal neutrophils. Blood 82: 2182–2187.

McCawley LJ, Korchak HM, Douglas SD, Campbell DE, Thornton PS, Stanley CA, Baker L, Kilpatrick L 1994 In vitro and in vivo effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on neutrophils in glycogen storage disease type 1B: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor therapy corrects the neutropenia and the defects in respiratory burst activity and Ca2+ mobilization. Pediatr Res 35: 84–90.

Forehand JR, Pabst MJ, Phillips WA, Johnston RB Jr 1989 Lipopolysaccharide priming of human neutrophils for an enhanced respiratory burst. Role of intracellular free calcium. J Clin. Invest 83: 74–83.

Visser G, Herwig J, Rake JP, Niezen-Koning KA, Verhoeven AJ, Smit GPA 1998 Neutropenia and neutrophil dysfunction in glycogen storage disease type 1c. J Inherited Metab Dis 21: 227–231.

Veiga-da-Cunha M, Gerin I, Chen Y, de Barsy T, de Lonlay P, Dionisi-Vici C, Fenske CD, Lee PJ, Leonard JV, Maire I, McConkie-Rosell A, Schweitzer S, Vikkula M, Schaftingen van E 1998 A gene n chromosome 11q23 coding for a putative glucose-6-phosphate translocase is mutated in glycogen-storage disease types 1b and 1c. Am J Hum Genet 63: 976–983.

Wolf BA, Colca JR, Comens PG, Turk J, McDaniel ML 1986 Glucose 6-phosphate regulates Ca2+ steady state in endoplasmatic reticulum of islets. J Biol Chem 35: 16284–16287.

Benedetti A, Fulceri R, Romani A, Comporti M 1987 Stimulatory effect of glucose 6-phosphate on the non-mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in permeabilized hepatocytes and Ca2+ release by inositol trishosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta 928: 282–286.

Kuijpers TW, Tool AT, Van der Schoot CE, Ginsel LA, Onderwater JJ, Roos D, Verhoeven AJ 1991 Membrane surface antigen expression on neutrophils: a reappraisal of the use of surface markers for neutrophil activation. Blood 78: 1105–1111.

Lew PD, Monod A, Waldvogel FA, Dewald B, Baggiolini M, Pozzan T 1986 Quantitative analysis of the cytosolic free calcium dependency of exocytosis from three subcellular compartments in intact human neutrophils. J Cell Biol 102: 2197–2204.

Niessen HW, Verhoeven AJ 1992 Differential up-regulation of specific and azurophilic granule membrane markers in electropermeabilized neutrophils. Cell Signal 4: 501–509.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. A. T. J. Tool and Prof. D. Roos for their help and stimulating discussions in the course of these studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Verhoeven, A., Visser, G., Van Zwieten, R. et al. A Convenient Diagnostic Function Test of Peripheral Blood Neutrophils in Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ib. Pediatr Res 45, 881–885 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199906000-00018

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199906000-00018

This article is cited by

-

Survival, but not maturation, is affected in neutrophil progenitors from GSD‐1b patients

Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease (2012)

-

Glycogen storage disease type I and G6Pase-β deficiency: etiology and therapy

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2010)

-

Association of glycogen storage disease 1b and Crohn disease: results of a North American survey

European Journal of Pediatrics (2002)

-

Historical highlights and unsolved problems in glycogen storage disease type 1

European Journal of Pediatrics (2002)