Abstract

To evaluate the effect of long-term treatment with recombinant human GH(rhGH) on renal function in short children with nephropathic cystinosis with and without concomitant cysteamine treatment, 36 growth-retarded children with nephropathic cystinosis (age 7.3 ± 2.7 y; creatinine clearance(CCR) 50 ± 27 mL (min × 1.73 m2)-1 were treated with 1 IU rhGH/kg/wk for up to 5 y. The rise in serum creatinine before and during rhGH treatment was compared with that in a historical control group of cystinotic patients. The effect of concomitant cysteamine treatment on the evolution of renal function before and after the start of rhGH was evaluated separately in patients without (group A) and with cysteamine treatment (group B). The decline of CCR was also compared with that in noncystinotic patients with chronic renal failure with and without rhGH treatment. At study entry, serum creatinine values in group A were similar to those in the historical controls, whereas group B had significantly lower serum creatinine values. Treatment with rhGH did not accelerate the rise in creatinine independently of cysteamine treatment. There were no significant differences in the mean decline of CCr per year in cystinotic compared with noncystinotic patients with chronic renal failure with or without rhGH treatment. rhGH therapy for up to 5 y does not accelerate the deterioration of renal function. This justifies the continuation of controlled studies of rhGH treatment in these patients. The study also provides further evidence that cysteamine therapy reduces the progression of renal failure in children with cystinosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Nephropathic cystinosis is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by intracellular storage of free cystine in various organs, predominantly the kidney(1–3). Untreated patients develop end-stage renal failure at an average of 9 y(4, 5). There is evidence that treatment with cysteamine, a cystinedepleting agent, slows the progression of renal glomerular disease, although it does not prevent the development of Fanconi syndrome(4, 6, 7).

Most children with nephropathic cystinosis develop severe growth retardation(2, 6, 8, 9). Cysteamine treatment may prevent growth retardation to a certain extent when administered from early infancy onward(4, 6), but does not induce catch-up growth in children who are already growth-retarded(7). rhGH treatment has been proven to be effective in promoting growth in short children with chronic renal failure for a treatment period of up to 5 y(10, 11). There is evidence that rhGH also markedly improves growth velocity in children with nephropathic cystinosis(10, 12, 13). However, concern has been raised that rhGH therapy might induce an accelerated rise of serum creatinine levels, resulting in the anticipated need for renal replacement therapy(14). This study analyzes the course of renal function in 36 short children with nephropathic cystinosis before dialysis entered into a trial of rhGH treatment.

METHODS

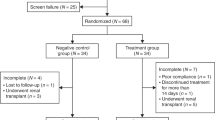

Patients. An open-label European multicenter study was initiated by the principle investigators (O.M., M.B., W.G.v.H.) in 1990 to evaluate the efficacy and safety of rhGH treatment in short children with nephropathic cystinosis(13). Sixty-four patients, 44 on conservative treatment, 9 on dialysis, and 11 with renal allografts have been included in this study, fulfilling the following inclusion criteria:1) growth retardation defined as a height SDS for chronologic age of≤ 2.0 and/or a height velocity SDS for chronologic age ≤0 using the first Zurich longitudinal study asreference (15);2) age >2 y; 3) first clinical signs of puberty present for no more than 1 y; 4) at least three separate height measurements during the previous year performed at the clinic of the responsible investigator; 5) cysteamine treatment, when used, had been started at least 1 y before rhGH and was continued during the study period;6) normal thyroid function levels or, if hypothyroid, and had been started on thyroid hormone treatment at least 1 y before rhGH; 7) no diabetes mellitus according to WHO criteria; 8) absence of severe renal osteodystrophy; and 9) written informed consent of patients and parents. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg and the local Ethics Committees of the participating centers.

To analyze the effect of rhGH on the course of renal function, this evaluation was restricted to 36 patients on conservative treatment with normal(n = 5) or reduced (n = 31) renal function (i.e. calculated CCR < 80 mL (min × 1.73 m2)-1 with a follow-up period of more than 1 y. Baseline clinical data are shown in Table 1.

To evaluate the influence of concomitant cysteamine treatment on the course of renal function before and after start of rhGH therapy, two subgroups were defined. The arbitrary separation into group A and B was based on the assumption that cysteamine is more effective if given early in the course of the disease and continuously over a long period of time.

Group A. Group A (no or short-term cysteamine treatment;n = 21) included children without cysteamine therapy at any time(n = 6), late onset of treatment (age > 3 y), and/or a short duration of treatment (<2 y time) (n = 15). Mean age at start of cysteamine was 4.3 ± 2.3 y, and mean duration of cysteamine treatment was 1.8 ± 1.7 y.

Group B. Group B (cysteamine treatment; n = 15) included children with the start of cysteamine therapy before 3 y of age and with duration of treatment for at least 2 y before rhGH. Mean age at start of cysteamine was 1.8 ± 0.6 y, and mean duration of cysteamine treatment 5.7 ± 2.1 y. The median prescribed cysteamine dosage was 45 (35-75) mg(kg × d)-1 for those patients who received cysteamine. There were insufficient data on leukocyte cystine concentrations to allow analysis of compliance.

Study medication. rhGH (Genotropin®, Pharmacia & Upjohn, Stockholm, Sweden) was administered at a weekly dose of 1 IU/kg in daily evening s.c. injections.

Physical and laboratory assessments. Standard anthropometry was performed at three monthly intervals. At each visit to the clinic, blood samples were taken for measurement of serum creatinine and urea. The measurements were performed by autoanalyzer in the individual centers. GFR was estimated by CCR according to the method of Schwartz et al.(16), using the formula: CCR = height [cm] ×F/serum creatinine [mg/dL]. The factor F varied between 0.45 and 0.55 as reported by the individual centers. In addition, CIN measurements (optional) were performed (using standard techniques) in some centers (Heidelberg, London, Lyon, and Paris) in 12 children at baseline and after 1 y of rhGH treatment. A 24-h urine sample was used for assessment of calcium and protein excretion. Urinary protein excretion was measured by the Biuret method.

To analyze the progression of renal failure before rhGH treatment, the participating centers reported all available serum creatinine values of their patients determined before the start of rhGH. The individual rise in serum creatinine levels was compared with that of 116 control cystinotic patients(who did not receive cysteamine or rhGH) using standards of serum creatinine class values given by Manz and Gretz(5). In addition, the change of calculated CCR per year was compared with the change of calculated CCR in 1) noncystinosis control patients with CRF without rhGH treatment taken from the European Study on Dietary Intervention(17) (age 9.0 ± 4.2 y) and 2) short noncystinotic patients with CRF treated with rhGH within the German Study Group on Growth Hormone Treatment in Chronic Renal Failure(10) (age 8.3 ± 3.4 y). The majority of patients of the “control” groups suffered from renal hypoplasia or dysplasia.

Statistical analysis. Values are expressed as mean ± SD, if not indicated otherwise. For comparison of the rise in serum creatinine in rhGH treated and control patients the progression charts of Manz and Gretz(5) were used. The number of patients progressing within a certain range (0.0-50.0 centile and 50.0-100.0 centile) was counted and analyzed in a cross table by Fisher's exact test according to the method proposed by Gretz(18).

Comparisons between groups were performed by ANOVA, followed by Duncan's multiple rank test. Longitudinal within-group differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA for repeated measurements. Statistical significance was accepted for p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Growth. During the first treatment year mean height velocity of the 36 patients increased from 4.1 ± 1.6 cm/y before the start of rhGH to 8.8 ± 2.5 cm/y, and height SDS improved within 1 y from -4.2± 1.0 to -3.3 ± 1.0. In nine patients treated for 4 y or more, mean height SDS improved by 1.7 ± 0.9 SDS within 4 y. A detailed analysis of complete growth data of the total study population (including dialysis and transplant patients) will be published separately.

Rise of serum creatinine concentration. The individual rise in serum creatinine values with increasing age was plotted into the progression charts of Manz and Gretz(5) (Fig. 1,A and B). In the subgroup (A) without cysteamine treatment, the number in the different centile ranges of the progression charts did not differ from the historical control group (Table 2; p = 0.12), either at the start of rhGH treatment, or at the time of the last observation. In contrast, in the cysteamine-treated group (B), only 2 out of 15 patients had an early rise in serum creatinine at baseline (Table 2; p = 0.0062), and there was no change with rhGH treatment. The individual curves of the total group with rhGH treatment showed a significantly (p = 0.0064) later rise in serum creatinine levels than the historical control group (Table 2). Serum urea concentration remained stable during the first study year (9.2 ± 4.2versus 7.8 ± 4.8 mmol/L)

Rise in serum creatinine levels of patients with no or short-term cysteamine treatment (panel A) and of patients with long-term cysteamine treatment (panel B) plotted on the creatinine centiles of a historical control group (-, 5th, 50th, and 95th centile)(5), - - - - -, pretreatment period; -, treatment period. Statistical evaluation seen from data of Table 2.

GFR. Mean CCR decreased during the year before rhGH treatment as well as during the study period (Fig. 2). The decline of CCR was compared with the recently published data of noncystinotic patients without rhGH treatment from the European Study on Dietary Intervention(17), as well as to the data of rhGH-treated short children with chronic renal failure from the German Study Group(10). The absolute loss of CCR during the year before rhGH treatment was higher in the present study than during the pretreatment period in the other two studies, whereas the change of CCR during the 3-y study period did not differ significantly in the three studies (Fig. 2). In nine patients with an observation period of at least 4 y, mean loss of GFR was 12.8 mL (min × 1.73 m2)-1 within 4 y.

Course of CCR in patients with nephropathic cystinosis before and during rhGH treatment (▾-▾) in control patients with CRF without rhGH treatment taken from the European Study on Dietary Intervention (○- - - -○)(17), and in short noncystinotic patients with CRF treated with rhGH within the German Study Group on Growth Hormone Treatment in Chronic Renal Failure (▵-▵)(10). Data are given as mean ± SEM.

CIN values were obtained in 12 patients at start and after 1 y of rhGH treatment (Table 3). Serum creatinine in these patients was 107.8 ± 51.2 μmol/L at the start and 135.3 ± 66.3 μmol/L after the first treatment year. Calculated CCR overestimated the “true” GFR (CIN) by 13%. However, the mean change of GFR/y measured by both methods did not differ significantly.

In the same patients, urinary protein excretion was 3.8 ± 2.0 g(m2 × d)-1 at the start and 1.9 ± 1.0 g (m2× d)-1 after 1 y of rhGH treatment. Urinary calcium per creatinine excretion was 0.85 ± 0.54 mmol/mmol of creatinine at the start and 0.71 ± 0.44 after 1 y of rhGH treatment (normal range<0.74 mmol/mmol of creatinine).

DISCUSSION

Preliminary data from previous studies(10–12) and the present study(13) on the use of rhGH in short patients with nephropathic cystinosis that have shown a beneficial effect on growth(10, 11) are encouraging. However, there is concern that rhGH treatment may accelerate the progression of CRF and may induce an early need for renal replacement therapy(14). The present study provides strong evidence that treatment with rhGH for up to 5 y does not accelerate the progression of CRF in a large cohort of children with nephropathic cystinosis at various stages of renal function.

Data from a historical control group of patients with nephropathic cystinosis suggests that patients develop chronic renal failure at a mean age of 3 y and reach end-stage renal failure at a mean age of 9 y(4, 5). Treatment with cysteamine postpones the need for renal replacement therapy by some years(4, 6, 7, 19), but only if treatment is started before the age of 2 y and the patients remain compliant. Cysteamine treatment also appears to improve growth in these patients(4, 6). However, despite early and appropriate cysteamine treatment, many children do not grow adequately, and statural height falls below the third centile(7).

In 1992, Andersson et al.(14) reported their experience with 2 y of treatment with rhGH in three short children with nephropathic cystinosis. They reported an accelerated rise of serum creatinine. This is not confirmed by our investigation. Our data demonstrate that at baseline the serum creatinine values of noncysteamine-treated patients(group A) did not differ from the historical control group. The rise in serum creatinine followed the centiles of Manz and Gretz(5). In addition, the point at which serum creatinine began to rise more sharply did not coincide with the start of rhGH treatment. Patients on long-term cysteamine treatment (group B) had a later increase in serum creatinine than did those with short-term or no cysteamine treatment. The rise of serum creatinine was again parallel to the centiles. Although, in this multicenter trial, there were insufficient data on leukocyte cystine concentrations to evaluate compliance to cysteamine therapy, this finding suggests a positive effect of cystine-depleting agents in preserving renal function. It confirms the observation of Schneider et al.(20) who also used the serum creatinine class values of Manz and Gretz(5). In our study this effect was independent of rhGH treatment.

It is conceivable that a more contemporary control group would demonstrate a much better renal survival than the historical control group. However, this trial of rhGH was undertaken in a selection of severely affected cystinotic patients (i.e. the shortest). It is possible that this selected group has a more rapid decline in renal function compared with unselected patients. Therefore, it seems justified to compare our patients with the historical control group of Manz and Gretz(5).

The annual change of CCR in the present investigation was compared with that in noncystinotic patients with CRF, either treated or nontreated with rhGH. The comparison (Fig. 2) showed a higher loss of CCR in the cystinotic patients during the 1-y run-in period than in the other two groups, whereas the change of CCR was only slightly higher during the 2 y of rhGH treatment. In addition, the mean loss of 13 mL (min× 1.73 m2)-1 within 4 y in the cystinotic patients is comparable to the mean loss of GFR in noncystinotic children with CRF treated with rhGH in the American Study of Fine et al.(11). These observations provide further evidence that rhGH does not lead to an accelerated deterioration of renal function.

We have confirmed in this study the well known observation that CCR overestimates true GFR (as determined by CIN). However, the change of GFR/y measured by both methods was comparable in the 12 patients in whom it was evaluated by CIN and CCR in parallel during the first treatment year. It might be argued that measurement of creatinine is not appropriate for assessment of renal function in patients treated with rhGH, because rhGH increases height and disproportionately muscle mass(21) and by this the endogenous source of creatinine. However, an increased creatinine production rate can cause an over-but not an underestimation of the rise in serum creatinine. The Schwartz formula(16) for estimation of CCR is based on the assumption that an increase in height (numerator) is balanced by an increase in muscle mass reflected by the serum creatinine concentration (denominator). Again, disproportionate increase of muscle mass by rhGH treatment would lead to an underestimation and not to an overestimation of CCR.

The observation that rhGH did not lead to a rapid deterioration of renal function is in line with observations in animals and humans with CRF. Although an rhGH-induced increase in GFR followed by glomerular sclerosis was reported in rodents without CRF(22), no hyperfiltration was noted in rats(23) or humans(24) with CRF. Recent clinical experience in short-term controlled(25, 26) and uncontrolled(10, 11) studies in children with CRF with observation periods for up to 5 y also do not support the view that rhGH results in an accelerated rise in serum creatinine and decline of GFR.

Rodent experiments have further evidenced that rhGH treatment concomitantly with 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment leads to hypercalciuria and eventually to renal damage(27). Patients with nephropathic cystinosis often present with hypercalciuria(28). In addition, almost all patients in the present study received 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment for metabolic bone disease. It is therefore important to note that no increase of urinary calcium excretion was observed during the 1st y of rhGH treatment. Concomitantly, no increase of urinary protein excretion, a factor highly correlated with the decline of renal function(17) was noted. These results are in line with the observation in noncystinotic children with CRF treated concomitantly with growth hormone and 1,25-(OH)2D3(29).

In conclusion, the present study provides strong evidence that rhGH treatment in short children with nephropathic cystinosis does not accelerate the deterioration of renal function. Therefore, the continuation of controlled prospective studies appears to be justified in those cystinotic patients who urgently need treatment of growth failure.

Abbreviations

- rh:

-

recombinant human

- CCR:

-

creatinine clearance

- CIN:

-

inulin clearance

- CRF:

-

chronic renal failure

- SDS:

-

SD score

References

Bickel H, Smallwood WC, Smellie JM, Barr HS, Hickmans EM, Harris H, Astley R, Teall GC, Douglas A, Philpott MG, Harvey CC, Finch E 1952 Cystine storage disease with amino-aciduria and dwarfism (Lignac-Fanconi disease). Acta Paediatr 42( suppl 90): 247–257

Broyer M, Guillot M, Gubler MC, Habib R 1981 Infantile cystinosis: a reappraisal of early and late symptoms. Adv Nephrol 10: 137–166

Gahl WA, Schneider JA, Aula PP 1996 Lysosomal transport disorders: cystinosis and sialic acid storage disorders. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Shy WS, Valle D (eds) The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease, 7th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 3763–3782

Markello TC, Bernardini IM, Gahl WA 1993 Improved renal function in children with cystinosis treated with cysteamine. N Engl J Med 328: 1157–1162

Manz F, Gretz N 1994 Progression of chronic renal failure in a historical group of patients with nephropathic cystinosis. Pediatr Nephrol 8: 466–471

Gahl WA, Reed GF, Thoene JG, Schulman JD, Rizzo WB, Jonas AJ, Denman DW, Schlesselman JJ, Gorden BJ, Schneider JA 1987 Cysteamine therapy for children with nephropathic cystinosis. N Engl J Med 316: 971–977

van't Hoff WG, Gretz N on behalf of the British Association for Paediatric Nephrology 1995 The treatment of cystinosis with cysteamine and phosphocysteamine in the United Kingdom and Ire. Pediatr Nephrol 9: 685–689

Winkler L, Offner G, Krull F, Brodehl J 1993 Growth and pubertal development in nephropathic cystinosis. Eur J Pediatr 152: 244–249

Broyer M, Tete MJ, Gubler MC 1987 Late symptoms in nephropathic cystinosis. Pediatr Nephrol 1: 519–524

Haffner D, Wühl E, Tönshoff B, Mehls O for the German Study Group on Growth Hormone Treatment in Chronic Renal Failure 1994 Growth hormone (GH) treatment in short children with chronic renal failure(CRF): a 5 years follow-up. Pediatr Nephrol 8:C40.

Fine RN, Kohaut E, Brown D, Kuntze J, Attie KM 1996 Long-term treatment of growth retarded children with chronic renal insufficiency, with recombinant human growth hormone. Kidney Int 49: 781–785

Wilson DP, Jelley D, Stratton R, Coldwell JG 1989 Nephropathic cystinosis: Improved linear growth after treatment with recombinant human growth hormone. J Pediatr 115: 758–761

van't Hoff WG, Wühl E, Offner G, Mehls O, for the European Study Group 1993 Growth in children with nephropathic cystinosis. Pediatr Nephrol 7( suppl): C7

Andersson HC, Markello T, Schneider JA, Gahl WA 1992 Effect of growth hormone treatment on serum creatinine concentration in patients with cystinosis and chronic renal disease. J Pediatr 120: 716–720

Prader A, Largo RH, Molinari L, Issler C 1988 Physical growth of Swiss children from birth to 20 years of age. Helv Paediatr Acta 52( suppl): S1–S125

Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelman CM 1976 A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 58: 259–263

Wingen AM, Fabian-Bach C, Schaefer F, Mehls O, for the European Study Group for Nutritional Treatment of Chronic Renal Failure in Childhood 1997 Failure in Childhood 1997 Randomised multicentre study of a low-protein diet on the progression of chronic renal failure in children. Lancet 349: 1117–1123

Gretz N 1994 How to assess the rate of progression of chronic renal failure in children?. Pediatr Nephrol 8: 499–504

Gahl WA, Schneider JA, Schulman JD, Thoene JG, Reed GF 1990 Predicted reciprocal serum creatinine at age 10 years as a measure of renal function in children with nephropathic cystinosis treated with oral cysteamine. Pediatr Nephrol 4: 129–135

Schneider JA, Clark KF, Greene AA, Reisch JS, Markello TC, Gahl WA, Thoene JG, Noonan PK, Berry KA 1995 Recent advances in the treatment of cystinosis. J Inherit Metab Dis 18: 387–397

Tönshoff B, Mehls O, Heinrich U, Blum WF, Ranke MB, Schauer A 1990 Growth-stimulating effects of recombinant human growth hormone in children with end-stage renal disease. J Pediatr 116: 561–566

Wanke R, Hermann W, Folger S, Wolf E, Brem G 1991 Accelerated growth and visceral lesions in transgenic mice expressing foreign genes of the growth hormone family: an overview. Pediatr Nephrol 5: 513–521

Ritz E, Tönshoff B, Worgall S, Kovacs G, Mehls O 1991 Influence of growth hormone and insulin like growth factor-I on kidney function and kidney growth. Pediatr Nephrol 5: 509–512

Haffner D, Zacharewicz S, Mehls O, Heinrich U, Ritz E 1989 The acute effect of growth hormone on GFR is obliterated in chronic renal failure. Clin Nephrol 32: 266–269

Hokken-Koelega ACS, Stijnen T, De Munch Keizer-Schrama SMPF, Wit JM, Wolff ED, de Jong MCJW, Donckerwolke RA, Abbad NCB, Bot A, Blum WF, Drop SLS 1991 Placebo controlled, double blind, cross-over trials of growth hormone treatment in prepubertal children with chronic renal failure. Lancet 338: 585–590

Fine RN, Kohaut EC, Brown D, Perlman AJ, for the Genentech Cooperative Study Group 1994 Growth after recombinant human growth hormone treatment in children with chronic renal failure: report of a multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Pediatr 124: 374–382

Kainer G, Nakao M, Massie FS Jr, Foreman JW, Chan JC 1991 Hypercalciuria due to combined growth hormone and calcitriol therapy in uremia: effects of growth hormone on mineral homeostasis in 75% nephrectomized weanling rats. Pediatr Res 30: 528–533

Black J, Stapleton FB, Roy S, Ward J, Noe HN 1986 Varied types of urinary calculi in a patient with cystinosis without renal tubular acidosis. Pediatrics 78: 295–297

Tönshoff B, Tönshoff C, Mehls O, Pinkowski J, Blum WF, Heinrich U, Stover B, Gretz N 1992 Growth hormone treatment in children with preterminal chronic renal failure: no adverse effect on glomerular filtration rate. Eur J Pediatr 15: 601–607

Acknowledgements

We thank Pharmacia & Upjohn, Stockholm, Sweden, for providing recombinant hGH (Genotropin®), and we thank Birgitta Lange-Sjöblom for help in organizing yearly study meetings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wühl, E., Haffner, D., Gretz, N. et al. Treatment with Recombinant Human Growth Hormone in Short Children with Nephropathic Cystinosis: No Evidence for Increased Deterioration Rate of Renal Function. Pediatr Res 43, 484–488 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199804000-00008

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199804000-00008

This article is cited by

-

Renal effects of growth hormone in health and in kidney disease

Pediatric Nephrology (2021)

-

Long-term growth hormone treatment in short children with CKD does not accelerate decline of renal function: results from the KIGS registry and ESCAPE trial

Pediatric Nephrology (2015)

-

Cystinosis: practical tools for diagnosis and treatment

Pediatric Nephrology (2011)