Abstract

Postnatal brain development of healthy prematurely born infants was assessed to study possible influence of premature birth and early extrauterine environment on structural, biochemical, and functional brain development. Myelination and differentiation of gray and white matter were studied byin vivo magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI), changes in cerebral metabolism by 1H MR spectroscopy (MRS), and changes in early human neurobehavior by the assessment of preterm infant's behavior (APIB). The stage of intrauterine and extrauterine brain development in prematurely born infants at term was compared with the stage of mainly intrauterine brain development in a group of full-term infants. Eighteen preterm infants unremarkable with respect to neurologic and medical status were studied at approximately 2 wk of postnatal age [gestational age (GA) 1: 32.5 ± 1.2 wk] and again at term(GA 2: 40.0 ± 1.1 wk). For comparison a group of 13 full-term born infants (GA T: 40.6 ± 2.1 wk) were studied by MR and six by APIB. When GA 2 to GA 1 was compared, significant maturational changes were found with MRI in gray and white matter and myelination, with 1H MRS in the concentration of N-acetylaspartate and with all scores of APIB. In preterm infants at term (GA 2) compared with full-term infants (GA T) significantly less gray and white matter differentiation and myelination was observed as well as significantly poorer performance in four neurobehavioral parameters (autonomic reactivity, motoric reactivity, state organization, attentional availability). We conclude that MRI and 1H MRS can be used to study postnatal brain development in preterm infants. Structural and biochemical maturation is accompanied by functional maturation as shown with the neurobehavior assessment. Preterm infants at term compared with full-term infants show a structural as well as a functional delay in brain development assessed at 40 wk of postconceptional age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Premature infants in neonatal care units must succeed in physiologic and behavioral adaptation to the extrauterine environment very early in their development. The ongoing debate centers on whether the extrauterine environment deprives infants of necessary stimulation(1), exposes infants to continuous overstimulation(2), or lacks a developmentally appropriate pattern of stimulation in accordance with the maturational stage of the infant(3).

Early human brain development includes growth and differentiation on the cellular(4), morphologic(5), and biochemical(4) level resulting in age-specific patterns of neurobehavior. Earlier morphologic methods allowed the description of human brain development between 10 and 44 wk of GA in autopsy tissue(5). About a decade ago, MRI and spectroscopy became unique tools to study morphologic(6, 7) as well as biochemical(8–10) changes in vivo. Myelination stands out as a continuously changing marker of maturation in the developing infant brain as it depends on the integrity of the neural network.

At parturition, full-term newborns have reached a level of organization as well as structural and biochemical maturation, appropriate for the typical stimuli presented by the extrauterine environment. However, infants who are born prematurely may be unprepared to integrate extrauterine environmental stimuli easily into their current developmental level(11, 12).

Paucity of knowledge about the structural and functional organization of the premature infant's brain and about the influence of the differences between intrauterine and extrauterine environment, led us to perform a longitudinal study, where changes in structure, biochemistry, and function in the premature infants' CNS were monitored throughout the infants' stay in a neonatal intensive care unit.

The hypotheses for this study were formulated as follows. 1) Objectivation of developmental alterations in growth, in structural and biochemical maturation and in behavioral functions in prematurely born babies studied at birth and again at expected term is possible using the noninvasive techniques of conventional MRI, localized 1H MRS, and APIB(13). 2) Babies who were born prematurely and who, therefore, reached the expected term outside the uterus, and babies who were born at term, who, therefore, completed their development up to that time inside the uterus show differences in their neurodevelopment expressed in structure, biochemistry, and neurobehavior.

METHODS

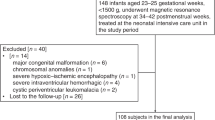

A group of 18 preterm infants appropriate in weight for GA [GA at birth: 30.5 ± 1.8 wk (range 28-32 wk); birth weight: 1345 ± 266 g], free of significant medical problems (exclusion criteria: 1) moderate to severe RDS requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation,2) perinatal acidosis or asphyxia, 4) intraventricular hemorrhage, 5) abnormal neurologic examination/seizures,6) sepsis, 7) intrauterine growth retardation,8) malformations, 9) severe hypoglycemia) were studied in their 1st to 3rd wk after birth (GA 1: 32.5 ± 1.2 wk) and again at term(GA 2: 40.0 ± 1.1 wk). The infants were monitored every 2 wk with head ultrasound and clinical neurologic assessment to exclude intermittent CNS abnormalities. All infants were started on enteral feeding early (1-2 d of life). The unit's policy at the time of the study was to supplement mothers milk with banked human breast milk. All the babies were fed fortified (85 kcal/100 mL) human breast milk and showed adequate weight gain throughout the study period. A group of 13 appropriate for GA full-term infants (GA at birth: 39.1 ± 0.9 wk; birth weight: 3230 ± 150 g), that were admitted to the hospital for observation due to suspected infection or mild self-resolving respiratory distress after birth, were studied by MR and six by MR and APIB (GA T: 40.6 ± 2.1 wk). The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for human research established by MR and the ethical committee of the study hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all parents.

MR. No sedation was used for the MR studies. A 1.5T MR unit was used for imaging and 1H MRS (Signa, General Electric). A specially designed MR incubator and cardiorespiratory monitoring were used for the infants' safety and comfort. We applied standard imaging techniques for T1 weighted images (TR: 400-600/TE: 14-20; number of acquisitions = 4) and T2 weighted images (TR: 3000/TE: 30-100; number of acquisitions = 2) using head coil or a 18-cm diameter extremity coil. Slice thickness was 3.5 to 4 mm for T1 weighted images, 4 mm for T2 weighted sequences. T1 weighted images were performed in the sagittal and axial plane, T2 weighted images in the axial plane. A localization image was obtained to position the voxel of 3.3 cm3 in the cerebrum (precentral area). For the acquisition of the spectra a stimulated echo pulse sequence was used; TR = 2000 ms, TE = 7 ms, TM= 35.5 ms(9, 14, 15).

Evaluation of gray-white matter differentiation and myelination was done according to a modified staging system introduced by McArdle et al.(6) (Table 1). Gray-white matter differentiation in T1 weighted sequences is characterized by increasing cortical enfolding and an increase in white matter signal intensity which can be classified in five different stages. Myelination, appearing hyperintense on T1-weighted MR images, follows a caudocranial spread during development and can be graded from stage 1 to 4 (Table 1). We added a stage 1.5 because we found the original stages(6) too far apart. Our stage 1.5 is based on the separation of the appearance of hyperintense signal in dorsal and ventral pons. The staging was performed separately by a neuroradiologist blinded to the GA of the assessed infant and a pediatrician trained in MR evaluation. Interrater variability was less than 10%.

For 1H MRS, the rectangular VOI was positioned in the precentral area of the cerebrum representing the later motor cortex area. For the acquisition of the spectra, STEAM was used with TR = 2000 ms, TE = 7 ms, TM = 35.5 ms. Estimations of molar concentrations of NAA, Cho, and M-Ino from1 H MRS data were done by using the chromatographically measured creatine concentrations, in region- and age-corresponding human autopsy tissue as an internal standard for the creatine peak area. Details of the 1H MRS method used are described elsewhere(9, 16).

APIB. We monitored the infants' reactions and behaviors in response to increasing stimulation along five subsystems of functioning:1) the autonomic or physiologic system (PHYSM), 2) the motor organizational system (MOTOM), 3) the state organizational system (STATM), 4) the attentional interactive system (ATTENM), and5) the self-regulation system, which includes two components(REGUM/EXFAM). REGUM presents a measure of the infants' capacity of self-regulation, and examiner facilitation is the amount of examiner facilitation necessary to regulate preterm infants behavior. The examinations were performed in a warm, quiet room where lighting was indirect and soft. The administration of the examination itself took 30 to 45 min. Scoring was performed according to the well established procedures(13, 17). All five system scores range from 1 to 9, 1 reflecting best performance and 9 compromised performance with poor behavioral differentiation. All examinations were performed by the same trained investigator. Interrater reliability with an independent trainer was maintained above 90%. The APIB is a modification of the well standardized Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale and has itself been standardized in various studies(13, 43).

Statistical analysis was performed using numerical data. Group comparison of MR and APIB scores and MRS concentration values in preterm and term newborns was performed by t test for independent means. t test for paired sample was used for comparison of GA 2 and GA 1 in the group of preterm infants examined at two different time points. Comparison of GA 2 and GA T between the group of preterm infants and the group of full-term infants was performed by a two-tailed t test for unpaired sample. Level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

The evaluation of the structural brain development with MRI shows a significant increase in gray-white matter differentiation and myelination, reflecting maturation when examination 1 (GA 1) was compared with examination 2 (GA 2) in the group of preterm infants. These pronounced changes in structure are shown in an axial T1 weighted image of a preterm infant at 31 and again at 40 wk of GA (Fig. 1,A and B).

Structural brain development in a preterm newborn GA 1 and GA 2, and differences in structural brain development in a preterm newborn at term (GA 2) compared with a full-term newborn (GA T). (A) Axial MRI (T1-weighted) preterm infant's brain (GA: 31 wk): cortex smooth, little to no convolution, thin bright rim of cortex, white matter low intensity [stage: gray-white matter differentiation stage (GW1) and myelination stage 1 (M1)].(B) Axial MRI (T1-weighted) preterm infant's brain at term (GA: 40 wk): cortex enfolded, a few to no visible spaces between folds, frontal white matter intensity low, frontal white matter not completely separated by insular infolds, myelin present in posterior limb of internal capsule, lenticular nucleus, and thalamus (stage: GW3 and M2). (C) Axial MRI(T1-weighted) full-term infants brain (GA: 40 wk): cortex extensively, compactly enfolded, no space visible between folds, increased white matter intensity, occipital patches of white matter disappear, myelin present in corona radiata (sagittal plane) (stage: GW5 and M4).

Assessment of the biochemical maturation by 1H MRS shows a significant increase in NAA from 4.5 mM at GA 1 to 6.3 mM at GA 2(Fig. 2 and Table 2). Cho-containing compounds and M-Ino showed no significant maturational changes (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

In terms of assessment of the functional maturation all APIB scores showed significant increase in differentiation and modulation when the examination at age 32 wk was compared with age 40 wk (Table 2).

Comparison of the structural, biochemical, and functional brain development of preterm infants grown to term with the development of full-term infants showed significant differences in gray-white matter differentiation and myelination between the two groups. Preterm infants at term showed less pronounced gray-white matter differentiation and a less advanced stage of myelination, two signs of structural delay (Fig. 1,B and C, Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the biochemical parameters NAA, Cho, and M-Ino concentration(Table 3).

Four out of the six neurobehavioral parameters measured showed less differentiated performance in the group of preterm infants at term compared with the full-term group. Differences were significant in PHYSM, MOTOM, STATM, and ATTENM (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

It has clearly been shown that pre- and perinatal biologic risk factors resulting in structural brain injury have a great impact on cognitive and neuromotor performance in infancy(19–23). The more subtle effects of prematurity in the absence of detected brain injury on behavior are just becoming noted as long-term follow-up studies appear in the literature showing minor disabilities not affecting overall cognitive function(24). Due to increased success in neonatal care, preterm infants are likely to spend a long period of time in an extrauterine environment different from the physiologic environment appropriate for their developing nervous system. Surroundings are different in regard to visual, auditory, and tactile stimuli; effects of gravity are much more pronounced; in the extrauterine environment, temperature differences are encountered. Composition and administration of nutrition is altered, all factors that are likely to influence organ development, including the brain(5).

Extrauterine maturation: longitudinal evaluation (GA 1 versus GA 2). In the first part of this study, we have longitudinally evaluated some aspects of extrauterine brain maturation during the last 8 wk of development up to the expected term in the human premature infant free of significant medical problems. By MRI, gray-white matter and stages of myelination were shown to differ significantly between mean postconceptional age 32.5 wk (GA 1) and 40.0 wk (GA 2). By MRS, a significant increase of NAA concentration was found between GA 1 and GA 2; in contrast, the concentrations of Cho and M-Ino did not vary. Behavior was tested using the APIB method: all six behavioral functions investigated differed significantly between GA 1 and GA 2. Thus, the methods used allowed us the in vivo monitoring of brain development in premature infants.

Development of the brain during gestation has been studied by various anatomists and pathologists who described the cytoarchitectural and myelogenic development of the CNS(25, 26). All of these descriptions were based on autopsy studies. McArdle et al.(6) presented the first staging system to evaluate human neonatal brain development in normal preterm and term newborns by in vivo MRI. The staging included a description of gray-white matter differentiation and myelination. The stages obtained at GA 1 for preterms and GA T for full-term infants in our study match their distribution of different stages in gray-white matter differentiation and myelination, indicating robustness of staging parameters. Differentiation of gray-white matter and myelination increase significantly with age. We have shown that extrauterine structural brain maturation takes place in prematurely born infants with features similar to those observed in autopsy studies of fetuses of various GA. From 31 wk gestation to 40 wk postconceptional age, brain surface changes from smooth surface and a few enfolds (e.g. calcarine sulcus, parietooccipital sulcus) to considerably enfolded surface with an increase of myelin in subcortical and cortical white matter.

Structural maturation takes place in close relation to biochemical maturation. Formation and deposition of myelin relies on the formation of lipids (cholesterol, glyco- and phospholipids) detected as structures of high signal intensity on T1 weighted images, as well as on neural activity(27). In vivo 1H MRS has been successfully used for the assessment of regional brain biochemistry in humans(28, 29). By studying newborns of different GAs, we and others have shown distinct developmental changes in various brain metabolites in different brain locations(9, 16, 30).

In the longitudinal observation of the present study, we have shown an increase in NAA in the precentral area, the presumed later motor function area, in all premature infants examined. It is not clear whether this finding is related to increased neuronal density (NAA having been shown to be a neuronal marker), or whether it indicates the beginning of myelin deposition(31–33). Cho and M-Ino showed no significant maturational changes. Kreis et al.(30) had observed a decrease in M-Ino concentration in the occipital lobe in term newborns a few weeks after birth. In the current longitudinal study, preterm infants assessed a second time, at the postconceptional age of 40 wk, approximately 8 wk after preterm birth, showed a tendency of lower M-Ino levels, which, however, did not reach significance.

The combination of detection of specific morphogenesis with the demonstration of the development of distinct behavior has been shown in animal models(34, 35). For investigation in the human premature infant, we used the APIB. This method is an extension of the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale(36). It provides an integrated subsystem profile of the infant's current ability to process environmental input and assesses the level of smooth, balanced functioning. We were able to detect functional brain maturation in all five subsystem categories measured by the APIB, the autonomic system, the motor system, the state-organizational system, the attention and interaction system and the self-regulatory, balancing system in preterm infants developing extrauterinely for up to 10 wk. Thus, under our conditions, brain structural and biochemical maturation as well as neurobehavioral maturation from wk 32 to 40 can be objectivated synchronically during extrauterine development of the human premature infant.

Comparison of intrauterine with extrauterine maturation: cross-sectional evaluation (GA 2 versus GA T). In the second part of this study, we have compared the same aspects of early structural and biochemical brain maturation as well as of functional behavior in a cross-sectional manner between the group of healthy preterm infants grown in the extrauterine environment to term (GA 2) and a group of full-term newborns (GA T). This comparison allows a direct appreciation of a possible impact of extrauterine life on brain structural, biochemical, and functional development of a premature infant growing to term. Gray-white matter differentiation and myelination were significantly retarded in premature infants at 40 wk compared with full-term infants. When evaluated individually, the MRI data of the preterm infants at term showed no stage 5 for gray-white matter differentiation with stages as low as stage 3, whereas the full-term infants showed stages 5 and 4 only. For myelination, preterm infants at term showed stages as low as 2, whereas the full-term group showed stages 3 and mainly 4. Therefore, the preterm infants grown to term appeared uniformly less mature at term than the full-term group. Two MR studies mention the question of differences between preterms at term and full-term infants, both claiming that no differences were noted, but both studies were not set out to address this question, and patient characteristics are insufficiently described(6, 37). In general, staging systems can never fully exclude observer bias for which automated quantification methods will be needed to confirm our findings in a more quantitative way. We are currently using automated segmentation of MRI data to generate absolute volume measurements during brain development(38).

Our MRI findings were paralleled by significantly less mature scores in the assessment of preterm infant behavior in the subsystem organization of autonomic reactivity, motor reactivity, state organization, and attentional availability. The scores for the self-regulatory ability and the complementary amount of examiner facilitation needed to achieve balance did not reach significant statistical difference. Small sample size most likely caused inability to detect less pronounced differences in self-regulatory abilities of the premature infant at term, as shown by others(18). Self-regulatory strategies are present and similar in preterm infants at term and full-term infants, but success in achieving balance in the preterm infant at term is more difficult because of its greater disorganization in the autonomic state and motor system. Differences in early neurodevelopment between preterm infants at term and full-term infants have been reported and results using the APIB agree with our findings(39, 40).

Unlike the delay observed in structural maturation and in the neurobehavioral maturation in preterm infants at term versus full-term infants, we did not detect any significant difference in the metabolite concentrations measured by 1H MRS. The structural assessment included a qualification of whole brain structures, as the biochemical assessment was limited to one small region, and results are known to vary in different regions of the brain(16). The precentral area of the brain represents a structure which can be identified early. In a region of advanced maturation, effects of prematurity might be less pronounced. This discrepancy could also be due to a different vulnerability of structural and biochemical maturation.

Changes in the electrophysiologic pattern of brain activity in preterm and full-term infants have produced controversial results with regard to acceleration or delay of electrical activity in preterm infants at term. Parmelee et al.(41) describe a similar burst-flat pattern observed in all preterm and full-term infants regardless of GA at birth, with longer burst periods in the preterm infant at term and interpret these data as acceleration of electrical activity. A less well organized sleep pattern, that we usually observe in preterm infants, could also be responsible for longer burst periods(42). Duffyet al.(18) studied brain maturation at 42 wk of postconceptional age in 135 healthy preterm and full-term infants using brain electrical activity mapping. They found consistently lower amplitudes for infants born earlier, which could represent earlier maturation. On the other hand they also found an increased latency in the baby visual evoked response in the preterm infants at term, which would suggest a delay in electrophysiologic functioning.

The crucial question of whether the extrauterine life of a prematurely born infant growing to term affects brain development is an issue which has been studied from different aspects-structure, biochemistry, electrophysiology, and behavior. The results do not show a uniform picture; there are data indicating developmental delays, developmental acceleration, or no apparent effects. The general consensus is that, if there are differences observable between term infants and premature infants at expected term, these “are small and dissipate completely shortly after the time of term”(43). We have shown significant delays by MRI in gray-white matter differentiation and myelination as well as in four out of six behavioral parameters. We found no statistically significant differences in 1H MRS and in two behavioral parameters. Taking the results of others and our own data into consideration, the question of whether the precocious extrauterine development of premature infants affects brain development cannot be answered in a general way. The outcome may depend on many factors: genetical, prenatal influences, delivery, postnatal management, nutrition, and major or minor complications. Furthermore, it cannot be assumed that brain development is a uniform event where all systems (structure, metabolism, behavior) develop synchronically and are uniformly affected by events occurring during extrauterine development. It may also be that effects are not apparent at term and become manifest only upon later challenges. Therefore, the comprehensive investigation of infants' development is mandatory. Reversibility and duration of the delay must be defined. In addition, the ability of specific, individualized interventions in avoiding or abolishing delays has to be investigated. Newer studies indicate that the extrauterine development could be influenced by integrating individualized behavioral care into the professional handling of premature infants in neonatal intensive care units(3, 40).

To find optimal conditions for support of neuromaturation in preterm infants, more needs to be known about the functional organization of the preterm infants' CNS. Further studies applying new MR techniques, such as functional MRI, will hopefully elucidate some of these issues and guide us in the optimal care for premature infants.

Abbreviations

- MR:

-

magnetic resonance

- MRI:

-

MR imaging

- 1H MRS:

-

proton MR spectroscopy

- VOI:

-

volume of interest

- NAA:

-

N-acetylaspartate

- Cho:

-

choline

- M-Ino:

-

myoinositol

- TR:

-

repetition time

- TE:

-

echo time

- GA:

-

gestational age

- APIB:

-

assessment of preterm infants' behavior

- PHYSM:

-

autonomic reactivity

- MOTOM:

-

motoric reactivity

- STATM:

-

state organization

- ATTENM:

-

attentional availability

- REGUM:

-

self-regulation

- EXFAM:

-

examiner facilitation

- STEAM:

-

stimulated echo pulse sequence

References

Resnick M, Eyler F, Nelson R 1987 Developmental intervention for low-birth-weight infants: improved early developmental outcome. Pediatrics 80: 68–74.

Long J, Lucey J, Philip A 1980 Noise and hypoxemia in the intensive care nursery. Pediatrics 65: 143–145.

Als H, Lawhon G, Brown E, Gibes R, Duffy FH, MacAnulty G, Blickman JG 1986 Individualized behavioral and environmental care for the very low birth weight preterm infant at high risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: neonatal intensvie care and developmental outcome. Pediatrics 78: 1123–1132.

Chi JG, Dooling EC, Gilles FH 1977 Gyral development of the human brain. Ann Neurol 1: 86–93.

Herschkowitz N 1988 Brain development in the fetus, neonate and infant. Biol Neonate 54: 1–19.

McArdle CB, Richardson CJ, Nicholas DA, Mirfakhraee M, Hayden CK, Amparo EG 1987 Developmental features of the neonatal brain: MR-imaging. Part I. gray-white matter differentiation and myelination. Radiology 162: 223–229.

Dubowitz LMS, Bydder GM 1990 Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in neonates. Semin Perinatol 14:3: 212–223.

Boesch Ch, Gruetter R, Martin E, Duc G, Wuthrich K 1988 Variations in the in vivo P-31 MR spectra of the developing human brain during postnatal life. Radiology 172: 197–199.

Huppi PS, Posse S, Lazeyras F, Burri R, Bossi E, Herschkowitz N 1991 Magnetic resonance in preterm and term newborns:1 H-spectroscopy in developing human brain. Pediatr Res 30: 574–578.

Peden CJ, Cowan FM, Bryant DJ, Sargentoni J, Cox J, Menon DK, Gadian DG, Bell JD, Dubowitz LM 1990 Proton spectroscopy of the brain in infants. J Comput Assist Tomogr 14: 886–894.

Als H 1982 Toward a synactive theory of development: promise for the assessment and support of infant individuality. Infant Mental Health J 4: 229–243.

Als H 1989 Self-regulation and motor development in preterm infants. In Lockman J, Hazen N (eds) Action in Social Context. Perspectives on Early Development. Plenum, New York, pp 65–97.

Als H, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB 1988 The APIB, an assessment of functional competence in preterm and fullterm newborns regardless of gestational age at birth. II. Infant Behav Dev 11: 319–331.

Moonen CTW, von Kienlin M, Cohen J, Gillen J, Daly P, Wolf P 1989 Comparison of single shot localization method (STEAM and PRESS) for in vivo proton NMR-spectroscopy. NMR Biomed 2: 201–208.

Posse S, Lazeyras F, Schuknecht B, Herschkowitz N, and Moonen CTW 1990 SMRM 1990 Proceedings 10th Annual Meeting, New York, Vol 13, p 1211(abstr)

Hüppi PS, Fusch Ch, Boesch Ch, Posse S, Burri R, Bossi E, Amato M, Herschkowitz N 1995 Regional metabolic assessment of human brain during development by 1H-MRS in vivo and by HPLC/GC in autopsy tissue. Pediatr Res 37: 145–150.

Als H, Lester BM, Tronick E, Brazelton TB 1982 Towards a research instrument for the assessment of preterm infant's behavior (APIB) and manual for the assessment of preterm infant's behavior (APIB). In HE Fitzgerald, BM Lester and MW Yogman (eds) Theory and Research in Behavioral Pediatrics. Plenum Press, New York, pp 35–63.

Duffy FH, Als H, McAnulty GB 1990 Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence for gestational age effects in healthy preterm and fullterm infants studied two weeks after due date. Child Dev 61: 1271–1286.

Byrne P, Welch R, Johnson MA, Darrah J, Piper M 1990 Serial magnetic resonance imaging in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr 117: 694–700.

Keenay SE, Adcock EW, Mc Ardle CB 1991 Prospective observations of 100 high risk neonates by high-field (1.5T) magnetic resonance imaging of the central nervous system. II. Lesions associated with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics 87: 431–438.

Keenay SE, Adcock EW, Mc Ardle CB 1991 Prospective observations of 100 high risk neonates by high field (1.5T) magnetic resonance imaging of the central nervous system. I. Intraventricular and extracerebral lesions. Pediatrics 87: 421–430.

DeVries LS, Connell JA, Dubowitz LMS, Oozar RC, Dubowitz V 1987 Neurological, electrophysiological and MRI abnormalities in infants with extensive cystic leukomalacia. Neuropediatrics 18: 61–66.

Volpe JJ 1992 Value of MR in definition of the neuropathology of cerebral palsy in vivo. AJNR 13: 79–83.

Largo RH, Molinar L, Kundu S, Lipp A, Duc G 1990 Intellectual outcome, speech and school performance in hig risk preterm children with birth weight appropriate for gestational age. Eur J Pediatr 149: 845–850.

Kostovic I 1990 Structural and histochemical reorganization of the human prefrontal cortex during perinatal and postnatal life. Prog Brain Res 85: 223–240.

Dorovini-Zis K, Dolman CL 1977 Gestational development of brain. Arch Pathol Lab Med 101: 192–195.

Reynolds R, Burri R, Herschkowitz N 1993 Retarded development of neurons and oligodendroglia in rat forebrain produced by hyperphenylalaninemia results in premanent deficits in myelin despite long recovery periods. Exp Neurol 124: 357–367.

Bottomley PA 1989 Human in vivo NMR spectroscopy in diagnostic medicine: Clinical tool or research probe. Radiology 170: 1–15.

Frahm J, Bruhn H, Gyngell ML, Merboldt KD, Hanicke W, Sauter R 1989 Localized proton NMR spectroscopy in different regions of the human brain in vivo. Relaxation times and concentrations of cerebral metabolites. Magn Reson Med 11: 47–63.

Kreis R, Ernst Th, Ross BD 1993 Development of the human brain: in vivo quantification of metabolite and water content with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med 30: 1–14.

Gill SS, Small RK, Thomas DGT, Patel P 1989 Brain metabolites as 1H-NMR markers of neuronal and glial disorders. NMR Biomed 2: 196–200.

Urenjak J, Williams SR, Gadian DG, Noble M 1992 Specific expression of N-acetylaspartate in neurons, oligodendrocyte-type-2 astrocyte progenitors, and immature oligodendrocytes in vitro. J Neurochem 59: 55–61.

Burri R, Steffen Ch, Herschkowitz N 1991 N-Acetyl-aspartate is a major source of acetyl groups for lipid synthesis during rat brain development. Dev Neurosci 13: 211–215.

Altman J 1987 Morphological and behavior markers of environmentally induced retardation of brain development: an animal model. Environ Health Perspect 74: 153–168.

Goldman-Rakic PS 1987 Development od cortical circuitry and cognitive function. Child Dev 58: 601–622.

Brazelton TB 1973 Neonatal behavioral assessment scale. Clin Dev Med 50

Konishi Y, Hayakawa K, Kuyiama M, Fujii Y, Sudo M, Konishi K, Ishii Y 1993 Developmental features of the brain in preterm and fullterm infants on MR imaging. Early Hum Dev 34: 155–162.

Huppi PS, Tsuji M, Kapur T, Barnes P, Zientara G, Kikinis R, Jolesz F 1995 3D-MRI: a new measure of brain development. Pediatr Res 37: 213A

Als H, Duffy FH, Mc Anulty GB 1988 Behavioral differences between preterm and fullterm newborns as measured with the APIB system scores. Infant Behav Dev 11: 319–331.

Als H, Lawhon G, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Gibes-Grossman R, Blickman JG 1994 Individualized developmental care for the very low birthweight preterm infant: medical and neurofunctional effects. JAMA 272: 853–858.

Parmelee AH, Akiyama Y, Stern E, Harris MA 1969 A periodic cerebral rhythm in newborn infants. Exp Neurol 25: 575–584.

Parmelee AH 1975 Neurophysiological and behavioral organization of premature infants in the first months of life. Biol Psychiatry 10: 501–512.

Volpe JJ 1995 Neurology of the Newborn, 3rd Ed. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, Chapt. 4, 131

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the MR team for their technical assistance, Dr. C. T. W. Moonen and Dr. S. Posse for the spectroscopy program source and their help in the implementation and improvement of the STEAM sequence, Dr. Roland Kreis for his help with spectroscopical data, Dr. Heidelise Als for excellent training in APIB, and the parents of the patients for consent to participation in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Funded by Swiss National Foundation (31-30909.91), Maurice Müller Foundation, Milupa SA., and Rossi Fonds.

Part of this work has been presented in abstract form[Pediatr Res 33:216A(abstr)].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hüppi, P., Schuknecht, B., Boesch, C. et al. Structural and Neurobehavioral Delay in Postnatal Brain Development of Preterm Infants. Pediatr Res 39, 895–901 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199605000-00026

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199605000-00026

This article is cited by

-

The potential effects of NICU environment and multisensory stimulation in prematurity

Pediatric Research (2020)

-

Neurobehaviour between birth and 40 weeks’ gestation in infants born <30 weeks’ gestation and parental psychological wellbeing: predictors of brain development and child outcomes

BMC Pediatrics (2014)

-

Functional brain maturation assessed during early life correlates with anatomical brain maturation at term-equivalent age in preterm infants

Pediatric Research (2013)

-

Resuscitation intensity at birth is associated with changes in brain metabolic development in preterm neonates

Neuroradiology (2013)