Abstract

This discussion paper describes a scoping exercise and literature review commissioned by the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) to inform their E-Quality programme which seeks to support small-scale educational projects to improve respiratory management in primary care. Our narrative review synthesises information from three sources: publications concerning the global context and health systems development; a literature search of Medline, CINAHL and Cochrane databases; and a series of eight interviews conducted with members of the IPCRG faculty. Educational interventions sit within complex healthcare, economic, and policy contexts. It is essential that any development project considers the local circumstances in terms of economic resources, political circumstances, organisation and administrative capacities, as well as the specific quality issue to be addressed. There is limited evidence (in terms of changed clinician behaviour and/or improved health outcomes) regarding the merits of different educational and quality improvement approaches. Features of educational interventions that were most likely to show some evidence of effectiveness included being carefully designed, multifaceted, engaged health professionals in their learning, provided ongoing support, were sensitive to local circumstances, and delivered in combination with other quality improvement strategies. To be effective, educational interventions must consider the complex healthcare systems within which they operate. The criteria for the IPCRG E-Quality awards thus require applicants not only to describe their proposed educational initiative but also to consider the practical and local barriers to successful implementation, and to propose a robust evaluation in terms of changed clinician behaviour or improved health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory and related respiratory allergic diseases are widely acknowledged as important global health issues.1 Diagnosis, treatment and care remain variable across different settings and countries. Primary care has a pivotal role in addressing the global challenge of non-communicable diseases including respiratory disease.2–4 Improving care by better implementation of guidelines has been identified by the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) as an important overarching theme in their Research Needs Statement.5,6

Educational interventions are often proposed as a strategy for improvement as n‘intuitively it would be assumed that training health professionals would enable them to acquire new skills and information and as a consequence patient outcomes would be improved’.7 Acquisition of knowledge, however, needs to be translated into behavioural change and ultimately improved patient outcomes.8

This discussion paper describes a scoping exercise and literature review commissioned by the IPCRG to inform their E-Quality programme, which seeks to support small-scale educational projects to improve quality of health outcomes for people with respiratory disease. The review addresses the merits of various educational and quality improvement approaches in improving outcomes in primary and respiratory care settings in order to inform evidence-based decisions about which projects to support. The diversity of their member countries and the broader global health agenda form an important context.

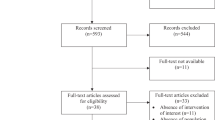

The scope of this review is broad and draws on diverse types of literature. We used three sources of material to inform the review: (1) publications concerning the global context and health systems development including empirical accounts of education and quality improvement work; (2) a literature search of Medline, CINAHL and Cochrane databases; and (3) a series of eight interviews conducted with members of the IPCRG faculty to explore the knowledge and experience of previous practice-based projects (see Box 1). The findings of the literature review and interviews were synthesised and themes were identified. We first report our findings related to the global healthcare context and then consider specific educational interventions and their potential to bring about change in clinical behaviour and improvement in patient outcomes.

The Global Health Agenda

The IPCRG sits within a broader global health community which has considered the role of education in strengthening health systems and improving health outcomes. Education has an important role to play, but a number of critical issues are apparent.

Variations in healthcare systems

It is widely acknowledged that there is significant variation in the strength of health systems.9 We draw on a definition provided by Roberts et al. which suggests that a ‘health system’ includes ‘all those who deliver care — public or private’, ‘the money flows that finance such care’, ‘the activities of those who provide specialised inputs into the health care process’, ‘financial intermediaries, planners and regulators’, and the ‘activities of organisations who deliver preventative services’.10 To address variation there has been significant investment in strengthening health systems globally,11 although many challenges remain.

Roberts et al. suggest that strategic health reforms designed to improve health systems should start by defining issues in terms of performance deficiencies, followed by causal diagnosis and policy development.10 These principles reflect widely adopted quality improvement approaches developed by the Institute for Health Improvement.12,13 Education and development may be an important strategy in changing clinician/team behaviours and achieving improved outcomes, but there are other determinants of health systems' performance such as financing, payments (or other incentives), organisation/service redesign or regulation.10 For example, a recent Cochrane review has explored ‘payments for performance’ as an intervention designed to achieve healthcare actions or targets in low and middle income countries.14 Schoen et al. recently identified poor coordination of care for patients with complex health needs across 11 countries.15 System redesign, payment innovation, information systems, improved coordination of care between providers, and engagement of patients in management of their care are all cited as potential components of a solution.15

It is therefore essential that, in designing and supporting any health system development (and we infer here any educational intervention), attention is given to understanding the issue to be addressed and the local circumstances in terms of economic resources, political circumstances, organisation, and administrative capacities. Educational interventions supported by the IPCRG will need to demonstrate sensitivity to the diverse local, regional, and national contexts in which they may take place. This conclusion resonated with the experience of the IPCRG interviewees (Box 2).

A global vision for reforming healthcare education

Frenk et al. propose that the education of health professionals requires significant global reform to address fragmented and outdated curricula which, they argue, produces graduates ill-equipped for the current challenges facing health systems.16 They set out an ambitious vision for improving pre-service education which includes both ‘instructional’ reforms (concerning what and how people learn) and ‘institutional’ reforms (concerning where education sits within an organisation or health system).

The proposed reforms advocate a more complex conception of the education of health professionals, which includes the needs of individuals in their local context but also considers how educational interventions sit within broader (local and global) health educational practices and infrastructures. This is important in a number of ways and holds relevant messages for the IPCRG E-Quality initiative. ‘Instructional reforms’ are not only concerned with technical/clinical skills and knowledge but also with developing shared values and skills essential for leading transformational change. The proposed reforms also encourage a questioning of existing educational practices and how interventions relate and contribute to broader health systems development. This is a richer and more complex understanding of learning and development which provides the foundation for evolving health systems to meet, for example, the challenge of long-term conditions.16

Global sharing of learning

The Global Health Workforce Alliance has proposed a framework which sets out clear principles and strategies to support education and training for health system development. This includes proposals for education and training which address local needs and are embedded within the health systems, increasing equity and efficiencies of scale through innovation in curriculum design and delivery and enhancing quality through leadership and collaboration.17

Traditionally, such international development work has concentrated on poorer and under-served populations.18 However, although developed countries may have unparalleled access to new science, technologies and expertise, their well established health systems and complex infrastructure can prove inflexible and difficult to change.19 Developed countries can learn a great deal about health and healthcare services from countries who are working with fewer resources and may have higher levels of innovation,19 offering opportunities to share learning between developing and developed countries.

The global health and international development literature provided the ‘big picture’ and overarching strategy which helped us to understand some of the wider context and clarified some important principles and values which are reflected in the IPCRG E-Quality criteria. We now consider the merits of a range of specific educational interventions.

What educational interventions bring about clinical behaviour change and improve patient outcomes?

We found a range of literature concerning the merits of different educational approaches.20,21 A critical issue is the link between knowledge and practice — what health professionals know and what they do; health professionals' knowledge does not necessarily translate into practice. Lack of high quality medical advice may be the result of a combination of low competence, poor individual motivation set in a healthcare context which is not conducive to improvement.22 Observations from the IPCRG faculty which complement the literature review are given in Box 3.

Education and continuing medical education

Education — including face-to-face teaching in small groups, seminars, interactive discussion or lectures — is often based on the premise of ‘transferring knowledge to practising professionals with an aim to change their practice’.23 Educational meetings alone, however, are unlikely to be effective in changing complex behaviours of healthcare professionals.24 Rigorous evaluation of standardised educational interventions are uncommon,25 and a systematic review of the effectiveness of continuing medical education (principally small group interactive seminars for general practitioners) in improving outcomes for patients with asthma was inconclusive.26

In contrast, a recent trial has shown that multifaceted educational programmes (or ‘blended learning’) which is sensitive to local circumstances and designed to build clinicians' sense of importance about change (‘why’) as well as their confidence to achieve change (‘how’) can reduce antibiotic prescriptions in primary care.27

Audit and feedback

Similarly, educational interventions may be more effective in improving professional practice and healthcare outcomes in combination with strategies such as audit and feedback, although the effects are variable28 and the benefits likely to be small in scale.24 Clinical audit in the context of diagnostic care provided to patients suspected of tuberculosis in a resource-poor setting was effective in improving quality when integrated with other health improvement programmes.29,30

Examples in the context of primary care management of respiratory conditions include a case study of audit and education which reduced technical errors in the performance of spirometry (and subsequent referrals) in a single general practice.31 Similarly, audit and feedback in the context of practice development plans produced improvements in the management of acute asthma.32 Audit and practice development underpins the Primary Care Respiratory Society UK's Quality Practice Award.33

Educational outreach and local opinion leaders

Educational outreach, defined as a ‘visit by a trained person to a health professional in his/her own setting’ in order to influence professional practice23 has been demonstrated to be an effective strategy to achieve small changes in practice;23,34 for example, in changing prescribing behaviours in primary care.35 Local opinion leaders are health professionals recognised by peers as ‘educationally influential’ who can, through education or supervision, influence the clinical behaviour of colleagues.23 One of the difficulties with this strategy is that it can prove difficult to identify effective local opinion leaders.35 Interventions are generally small scale and potentially use a disproportionate amount of resources.

Distance learning and online educational resources

Typically, distance learning is concerned with programmes and resources for learners who are not physically present in an educational setting. Learners, teachers/specialists with expertise, and educational materials may be separated by location and/or time differences. There is wide variation in the modes of distance learning and online educational resources available. At a simple level, educational materials may include printed and/or audio visual materials concerned with knowledge transfer and likely to be limited in changing professional behaviour.36

There are increasing numbers of technology-based educational resources. The advantages are that they allow easy access and flexibility, with the potential to train large numbers of participants. However, there are constraints and recognised barriers to e-learning for health professionals including cost, poor design of packages, inadequate technology, lack of skills, the need for a component of face-to-face teaching, the time-intensive nature of e-learning, and ‘computer anxiety’.37 Gensichen et al. used consensus methodology to study the potential of e-learning to provide effective education in general practice and concluded that, although there was a positive attitude to e-learning, there were concerns about the lack of alignment towards users' needs and the poor development of innovative didactic concepts.38

By their nature, many e-learning initiatives are accessed by individuals from diverse healthcare practices so that the educational design may lack attention to specific local contexts, educational support/facilitation may be limited and outcomes difficult to assess. A further practical limitation is their reliance on technology and internet access which may be an issue in resource-poor countries.

Reflecting earlier evidence on the benefits of multifaceted interventions,23,35 distance learning and online educational resources may be more likely to influence change in combination with other interactive strategies. For example, a multifaceted spirometry educational programme combining computer-based training with case-based learning supported by clinical experts using interactive webinars and a period of online ‘over reading’ and feedback has been shown to increase spirometry quality and assessment of asthma severity.39

Limitations

We did not undertake a systematic review, preferring to scope a very broad literature from which we were able to identify some consistent messages. The literature in this area is vast and diverse. We may have missed some important papers but, to reduce the risk of overlooking any key themes, we interviewed key members of the IPCRG with academic and practical experience of delivering educational programmes.

Conclusions

There is little evidence for the effectiveness of particular educational interventions either in changing health professional practice or, more significantly, in improving health outcomes as particularly the long-term effects of education on clinical practice have scarcely been studied. Too often the focus is on the process by which education is delivered rather than the outcome that is achieved for the person or persons to whom healthcare is delivered.40,41 This is not to belittle or denigrate educational initiatives but rather to encourage more rigorous thinking about the way that programmes are implemented and evaluated.

Educational interventions sit within complex healthcare, economic, and policy contexts42 and evaluations that seek to test specific approaches to education show equivocal results.43 We found some evidence of effectiveness amongst educational interventions that were carefully designed, multifaceted, engaged health professionals in their learning, provided ongoing support, were sensitive to local circumstances, and delivered in combination with other quality improvement strategies or incentives. The IPCRG therefore reflected these findings and this complex environment when designing the criteria for its E-Quality awards, requiring applicants to explain their healthcare context and consider the practical and local barriers when constructing their application (see E-Quality criteria in Box 4). A core requirement of E-Quality projects is to evaluate the intervention in terms of evidence of changed clinician behaviour and (ideally) improved health outcomes. Publication of their results over the forthcoming years should add to the literature on the merits of various educational and quality improvement approaches in improving outcomes in primary and respiratory care settings.

References

United Nations General Assembly: Sixty-sixth session. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. New York: United Nations, 2011.

World Health Organization. 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: WHO, 2008.

World Health Organization. Global Alliance against Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Action Plan 2008–2013. Geneva: WHO, 2008.

Bousquet J, Kiley J, Bateman ED, et al. Prioritised research agenda for prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Eur Respir J 2010;36:995–1001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00012610

Pinnock H, Thomas M, Tsiligianni I, et al. The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Research Needs Statement 2010. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19(Suppl 1):S1–S21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00021

Pinnock H, Ostrem A, Rodriguez MR, et al. Prioritising the respiratory research needs of primary care: the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) e-Delphi exercise. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21:19–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00006

Fletcher M . Continuing medical education (CME) for primary care health professionals. Prim Care Respir J 2004;13:136–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2004.05.001

Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD . Evaluating Training Programs. 3rd Edition. San Francisco, CA: Berrett Koehler Publishers, 2006.

World Health Organization. Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. WHO's Framework for Action. 2007. Available at http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf (accessed February 2012).

Roberts M, Hsiao W, Berman P, Reich M . Getting Health Reform Right. A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Shaw RP, Samaha H . Building Capacity for Health System Strengthening: A Strategy That Works. The World Bank Institute's Flagship Program on Health Sector Reform and Sustainable Financing, 1997–2008. Washington: World Bank Institute, 2009. Available from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTHSD/Resources/376278-1114111154043/1011834-1246449110524/ReflectionsonWBICapacityBuildinginHealth.pdf (accessed March 2012).

Institute for Health Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI's Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. IHI Innovation Series White Paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003. Available from http://www.IHI.org (accessed March 2012).

Leatherman S, Ferris TG, Berwick D, Omaswa F, Crisp N . The role of quality improvement in strengthening health systems in developing countries. Int J Qual Healthc 2010;22:237–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzq028

Witter S, Fretheim A, Kessy FL, Lindahl AK . Paying for performance to improve the delivery of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD007899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007899.pub2

Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty M, Pierson R, Applebaum S . New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Affairs 2011;30:2437–48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

Global Health Workers Alliance. Task Force for Scaling Up Education and Training for Health Workers. Scaling Up, Saving Lives. Geneva: WHO, 2008. Available from http://www.who.int/workforcealliance (accessed March 2012).

Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009;373:1993–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9

Crisp N . Turning the World Upside Down: The Search for Global Health in the 21st Century. London: Hodder Education, 2010.

Robertson R, Jochelson K . Interventions that change clinician behaviours: mapping the literature. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006. Available from http://www.nice.org.uk/media/AF1/42/HowToGuideKingsFundLiteratureReview.pdf (accessed March 2012).

University of York NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Effective Healthcare Bulletin: Getting Evidence into Practice. Vol. 5, No. 1, 1999.

Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K . The Quality of Medical Advice in Low Income Countries. Policy Research Working Paper 4501. The World Bank Development Research Group, 2008. Available from http://go.worldbank.org/FOKD38MST0 (accessed March 2012).

Siddiqi K, Newell J, Robinson MR . Getting evidence into practice: what works in developing countries? Int J Qual Healthc 2005;17:447–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzi051

Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2

Sheikh A, Khan-Wasti S, Price D, Smeeth L, Fletcher M, Walker S . Standardized training for healthcare professionals and its impact on patients with perennial rhinitis: a multi-centre randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;37:90–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02619.x

Barton C, Sulaiman N, Liaw S . Continuing medical education for asthma in primary care settings: a review of randomised controlled trials. Prim Care Respir J 2003;12:119–23.

Butler CC, Simpson SA, Dunstan F, et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted educational programme to reduce antibiotic dispensing in primary care: practice based randomised controlled trial BMJ 2012;344:d8173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d8173

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O'Brien MA, Oxman AD . Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2

Siddiqi K, Volz A, Armas L, et al. Can clinical audit, improve the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in three Latin American countries? Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:566–78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02035.x

Siddiqi K, Lee ACK . An integrated approach to treat tobacco addiction in countries with high tuberculosis incidence. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:420–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02238.x

Carr R, Telford V, Waters G . Impact of an educational intervention on the quality of spirometry performance in a general practice: an audit. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:210–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00006

Foster J, Hoskins G, Smith B, Lee AJ, Price D, Pinnock H . Practice development plans to improve the primary care management of acute asthma: randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2007;8:23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-8-23

Primary Care Respiratory Society UK. PCRS-UK Quality Award. Available from http://www.pcrs-uk.org/quality_award/index.php (accessed March 2012).

O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2

Grol R, Grimshaw RJ . From best evidence to best practice. Effective implementation of change in patient care. Lancet 2003;362:1225–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1

Farmer AP, Légaré F, Turcot L, Grimshaw J, Harvey E, McGowan J, Wolf FM . Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews July 2011. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD004398/printed-educational-materials-effects-on-professional-practice-and-health-care-outcomes. Accessed 1.8.12

Childs S, Blenkinsopp E, Hall A, Walton G . Effective e-learning for health professionals and students-barriers and their solutions. A systematic review of the literature–findings from the HeXL project. Health Info Libr J 2005;22(Suppl 2):20–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-3327.2005.00614.x

Gensichen J, Vollmar HC, Sönnichsen A, Waldmann UM, Sandars J . E-learning for education in primary healthcare–turning the hype into reality: a Delphi study. Eur J Gen Pract 2009;15:11–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13814780902864160

Stout JW, Smith K, Zhou C et al. Learning from a distance: effectiveness of online spirometry training in improving asthma care. A cluster randomised trial. Acad Pediatr 2012;12:88–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2011.11.006

Donabedian A . Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Quarterly 1966;83:691–729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x

Glasziou P, Del Mar C . The Stuart Patterson Lecture: The Epidemiology of Ignorance. Presented at the RACGP 49th Annual Scientific Convention, Brisbane, Australia. 2006. Available at http://www.racgp.org.au/asc2006/keynotes/glasziou (accessed March 2012).

Booth BJ, Snowdon T, Harris MF, Tomlins R . Safety and quality in primary care: the view from general practice. Aust J Prim Health 2008;14:19–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/PY08018

Grol R, Buchan H . Clinical guidelines: what can we do to increase their use? Med J Aust 2006;185:301–02.

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Anthony D'Urzo

Funding The IPCRG commissioned this work as part of the IPCRG e-Quality initiative. HP is supported by a Primary Care Research Career Award from the Chief Scientist's Office of the Scottish Government.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Professor Phillip Cotton to the scoping exercise, and members of the IPCRG Education Sub-committee who led the E-Quality award including Samantha Louw for administrative assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW, HP and HJF led the IPCRG E-Quality project. JM undertook the literature review and the interviews and synthesised the findings with the support of the co-authors and members of the IPCRG education subcommittee. JM wrote the initial draft of the paper, to which all the authors contributed. JM is the study guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

NHC, JCdeS, OMY and HP are Associate Editors of the PCRJ, but were not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish, this article. The authors have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDonnell, J., Williams, S., Chavannes, N. et al. Effecting change in primary care management of respiratory conditions: a global scoping exercise and literature review of educational interventions to inform the IPCRG's E-Quality initiative. Prim Care Respir J 21, 431–436 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00071

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00071

This article is cited by

-

Improving Primary Healthcare Education through lessons from a flock of birds

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2023)

-

Improving primary care management of asthma: do we know what really works?

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2020)

-

Building capacity to improve respiratory care: the education strategy of the International Primary Care Respiratory Group 2014–2020

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2014)