Abstract

Background:

Annual recording of the Royal College of Physicians three questions (RCP3Q) morbidity score is rewarded within the UK ‘pay-for-performance’ Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Aims:

To investigate the performance of the RCP3Q for assessing control in real-life practice compared with the validated Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) administered by self-completed questionnaire.

Methods:

We compared the RCP3Q score extracted from a patient's computerised medical record with the ACQ self-completed after the consultation. The anonymous data were paired by practice, age, sex, and dates of completion. We calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the RCP3Q scale compared with the threshold for good/poor asthma control (ACQ ≥1).

Results:

Of 291 ACQ questionnaires returned from 12 participating practices, 129 could be paired with complete RCP3Q data. Twenty-five of 27 patients who scored zero on the RCP3Q were well controlled (ACQ <1). An RCP3Q score ≥1 predicted inadequate control (ACQ ≥1) with a sensitivity of 0.96 and specificity of 0.34. Comparable values for RCP3Q≥2 were sensitivity 0.50 and specificity 0.94. The intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.13 indicated substantial variability between practices. Exacerbations and use of reliever inhalers were moderately correlated with ACQ (Spearman's rho 0.3 and 0.35) and may reflect different aspects of control.

Conclusions:

In routine practice, an RCP3Q score of zero indicates good asthma control and a score of 2 or 3 indicates poor control. An RCP3Q score of 1 has good sensitivity but poor specificity for suboptimal control and should provoke further enquiry and consideration of other aspects of control such as exacerbations and use of reliever inhalers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Objective assessment of current clinical control and future risk is the foundation of a routine asthma review, inviting consideration of the reasons for poor control and underpinning the subsequent development of management plans.1,2 Asthma control can be defined in a number of ways3 but, in primary care, important components are the presence of symptoms (assessed by asking specific morbidity questions), use of relief medication, and occurrence of exacerbations (normally recorded in the patient's healthcare record). Routinely assessing and recording the results of standardised questions (Patient Reported Outcome Measures, PROMS) has therefore been promoted by initiatives to improve standards of clinical practice,4,5 including within the Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF) a ‘pay-for-performance scheme’ in the UK.6

PROMS in research and clinical practice

The well-defined process for developing and validating PROMs7 is exemplified by the widely used Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)8,9 which has defined scores that represent well and poorly controlled asthma to aid clinical interpretation.3,10 Validity, however, needs to be assessed in relation to a specific purpose and setting.7 In a research context, instruments validated for the relevant context are chosen11 and administered by trained researchers using techniques which maximise the response rate and reduce completion errors.12 Use in the context of clinical care, however, introduces a range of poorly understood variables including the influence of diverse modes of administration and potential under- or over-reporting of symptoms by patients anticipating the response from their clinician. It cannot therefore be assumed that even the best validated PROM will deliver valid answers when used in routine clinical care.

The Royal College of Physicians three questions (RCP3Q): a PROM designed for use in clinical practice

The RCP3Q (Table 1) emerged from a UK consensus meeting of representatives of primary and secondary care and patient organisations as a clinical tool which ‘made sense to both clinician and patient’ and would be ‘widely used to improve standards of care’.13,14 Precursors of the RCP3Q (the Tayside Asthma Stamp and the Jones morbidity index) had been used in audits of asthma management15 by postal questionnaire to predict asthma exacerbations16,17 and, more recently, during telephone consultations to screen for patients who might benefit from a face-to-face review.18 When administered formally within a battery of questionnaires in a prospective observational study of 20 adults assessed 2-weekly for 12 weeks, there was a highly significant correlation between the RCP3Q and the ACQ (0.79, p<0.001) and a strong relationship between changes in both the scores.19

In the UK, annual recording of the RCP3Q has been introduced as an essential component of an annual asthma review within the QOF.6 This multicentre study aimed to investigate the performance of the RCP3Qs in a real-life practice setting compared with the gold standard of the ACQ administered by self-completed questionnaire, and to examine the additional predictive value of other contextual data.

Methods

Our validation study was undertaken during 2009–2011 in practices throughout the UK. Ethical approval was granted by North West 4 Research Ethics Committee (Reference 09/H1001/103) and governance approval was provided by the participating National Health Service (NHS) Trusts.

Practice recruitment

We approached the 30 practices participating in the QOF pilot (in which all potential QOF indicators are tested for reliability, validity, and feasibility)20 and, with the support of the local Primary Care Research Networks, extended recruitment to other practices in these areas. Practices were eligible if they provided proactive asthma care (usually led by an asthma trained nurse) during which they routinely recorded the RCP3Qs. We specifically asked nurses not to change their normal practice.

Patient recruitment

Participating practices were given between 20 and 40 questionnaires to distribute (according to list size), with additional questionnaires provided on request. Adults (18 years or over) with asthma were recruited as they attended the practice asthma clinic. The only exclusion criteria were people with other significant respiratory disease, those unable to complete a questionnaire in English, or at the discretion of the clinician for significant medical or social reasons.

Data collection and handling

All data were obtained anonymously.

ACQ

At the end of the consultation, eligible patients were invited (by the asthma nurse or other member of the practice team) to complete the study questionnaire which was returned in a prepaid envelope to the research team. The questionnaire included:

-

The validated ACQ (6-question version).9 The ACQ measures clinical goals of asthma management including use of reliever medication on a scale of 0 (good control) to 6 (poor control).9 The threshold between ‘well controlled’ and ‘not well controlled’ asthma is close to 1.00.10

-

Identifiers: name of practice, demographic details (age and sex), date of completion.

RCP3Qs

All the routinely recorded answers to the RCP3Q recorded in the practice during the time they were participating in the study were extracted using an automated search of the practice database (Optimum Patient Care (OPC), Norfolk, UK www.optimumpatientcare.org). The individual patient level data included:

-

Identifiers: practice code, demographic details (age and sex), date of completion.

-

The RCP3Qs as recorded on the practice computer. In the absence of standardised coding, practices were asked how they normally coded the responses to the questions and the search modified appropriately.

-

Asthma drugs prescribed in the previous year.

-

Acute exacerbations coded in the records.

Data handling

The RCP3Q and data from records were extracted electronically to a database held by OPC. The ACQ was entered onto a separate database at the University of Edinburgh. The RCP3Q and ACQ entries were matched if the practice, age, and sex were identical and if the dates of completion were within 24 hrs. In the event of two pairs of records with the same identifiers, both were discarded.

Sample size calculation

Based on the potential availability of up to 30 practices from the QOF pilot we estimated, using simulated data, that for a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 0.8 with confidence intervals of ±0.075, we would require a sample size of approximately 250 patients.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the sensitivity and specificity of each level of the RCP3Q scale compared with the validated ACQ threshold score of ≥1 and plotted a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, taking an area under the curve (AUC) of ≥0.8 to indicate good discrimination by the RCP3Q. We undertook additional analyses using ACQ thresholds of ≤0.75 (the optimal cut-off point to be confident that a patient has well controlled asthma6) and ≥1.5 (the optimal cut-off point to be confident that the patient has inadequately controlled asthma10). We examined variation between practices by making scatter plots of RCP3Q against ACQ for each practice. Statistical analysis was carried out in R 2.11 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

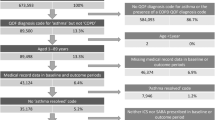

Twelve practices took part in the study; their details are shown in Table 2. During the study period these practices recorded items from the RCP3Q for a total of 916 patients. We provided a total of 360 questionnaires to the practices although it is likely that not all were distributed; 291 questionnaires were returned of which 139 could be paired with RCP3Q responses extracted from the practice computers. The flow diagram shown in Figure 1 gives details of the process of pairing. Ten patients were excluded because either the ACQ or RCP3Q was incomplete. The remaining 129 patients from the 12 practices had valid ACQ and RCP3 scores and were thus included in the subsequent analysis. The number of patients per practice ranged from 2 to 28. The mean (SD) age of the patients was 54 (17) years and 55 (43%) patients were male. The age, sex, and ACQ score of the 152 patients whose questionnaires could not be reliably paired were similar to those included in the analysis.

Questionnaire responses

The ACQ scores ranged from 0 to 5 with a mean (SD) of 1.08 (1.03). The RCP scores ranged from 0 to 3 with a mean (SD) of 1.14 (0.86) and median of 1. Table 3 compares the distribution of scores for the two scales and shows that 25/27 patients (92.5%) with an RCP3Q score of zero had an ACQ score <1 indicating ‘well controlled asthma’. In contrast, an ACQ score of ≥1 indicating ‘not well controlled asthma’ was recorded by 26/70 patients (37.1%) with an RCP3Q score of 1 and by 28/32 patients (87.5%) with an RCP3Q score of 2 or 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of RCP3Q and ACQ

The diagnostic accuracy of the RCP score was measured against the ACQ threshold value of 1.0 (the defined crossover point between ‘well controlled’ and ‘not well controlled’ asthma).10 With a cut-off RCP3Q score of ≥1, the sensitivity was 0.96 (95% CI 0.88 to 0.99) and specificity 0.34 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.46) while, with a cut-off RCP3Q score of ≥2, the sensitivity was 0.50 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.63) and the specificity was 0.94 (95% CI 0.87 to 0.98). These values are summarised in the ROC curve shown in Figure 2; the AUC was 0.79 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.81). The sensitivity and specificity of the RCP3Q compared with three different ACQ thresholds are shown in Table 4.

Relationship of RCP3Q score to good and poor control

An RCP3Q score of zero was recorded for 27 patients: only one of these patients (4%) had an ACQ score of ≥1.5 (the threshold above which patients can be confidently assumed to have inadequately controlled asthma10). In contrast, an RCP3Q score of 2 or 3 was recorded for 32 patients of whom only three (9%) had an ACQ score of <0.75 (the threshold below which patients can be confidently assumed to have well controlled asthma10). Thus, in practice, a zero RCP3 score effectively rules out poor control and an RCP3 score of 2 or 3 rules out good control. However, an RCP3Q score of 1 is less able to discriminate: 15 (21%) of the 70 patients with an RCP3Q score of 1 had an ACQ score of ≥1.5 (poor control), 37 (54%) had an ACQ score of <0.75 (good control) and 18 (25%) had scores between 0.75 and 1.5.

Patterns of RCP3Q response

Table 5 lists each of the possible permutations of symptoms on the RCP3Q and shows the mean ACQ score of patients who reported that pattern. In patients reporting only one symptom (RCP3Q=1), those with symptoms interfering with sleep had a higher mean ACQ than those who only experienced daytime symptoms. Of the 14 patients who only reported interference with sleep, six (43%) had an ACQ score of ≥1.5 indicating poor control compared with nine of 56 (16%) of those whose only symptom was in the daytime or during activity. Conversely, applying the lower ACQ threshold of <0.75, 32 of 56 patients (57%) with daytime symptoms or activity limitation were well controlled compared with five of 14 patients (36%) with disturbed sleep.

Additional records-based indicators of asthma severity

Both the number of reliever inhalers prescribed and the number of recorded asthma exacerbations in the previous year were associated with the ACQ score (Spearman's rho 0.30, p=0.001 and Spearman's rho 0.35, p<0.001, respectively) and with the RCP3Q score (Spearman's rho 0.28, p=0.003 and Spearman's rho 0.51, p<0.001). In view of this, we examined these record-based indicators of severity in order to see if they added predictive value. Given that an RCP3Q score of zero effectively ruled out poor control and a score of ≥2 made it highly likely, we limited this additional analysis to patients with an RCP3Q score of 1. These patients were categorised as meeting the record-based criterion for poor control if, in the last year, they had either been prescribed ≥4 reliever inhalers or had ≥1 recorded exacerbations. The ACQ score was ≥1 in 11/25 patients (44%) who met the record-based criterion and in 15/45 (27%) of those who did not, suggesting that it added relatively little additional value.

Variation between practices

Figure 3 shows the correlation between RCP3Q and ACQ scores among patients in each practice. The appearance suggests that, in two practices (J and L), almost all patients are rated as RCP3Q=1 despite reporting a range of ACQ scores, in some cases indicating poorly controlled asthma.

Discussion

Main findings

When used and recorded in routine practice, the RCP3Q delivered results that were broadly correlated with the ACQ although there was considerable variation between practices. In particular, an RCP3Q of zero indicated good control as assessed by the ACQ and an RCP3Q score of 2 or 3 indicated poor control. An RCP3Q score of 1, which was the most commonly reported score, was less helpful: only 34% had poor control (defined by ACQ ≥1), although those with daytime symptoms only were unlikely to have unequivocally poor control (ACQ ≥1.5). Recorded exacerbations and use of reliever inhalers added little to the predictive value of the RCP3Q when compared with the ACQ, which suggests that these parameters reflect different aspects of control. The range of suitable codes and substantial variability in the coding strategies between practices made data extraction very difficult.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The participating practices may not have been representative of the full range of clinical practice, although the QOF pilot20 recruited a representative sample of UK practices and additional practices were recruited within these demographically diverse areas.

The difficulty in matching questionnaire responses to data extracted from the electronic health record led to less than half of returned questionnaires being suitable for analysis, which reduced the statistical power of the study. As a result, confidence intervals were wider than anticipated and it was not possible to quantify variation between practices using linear mixed effects modelling. It may also have introduced bias, although patients' demography and ACQ scores were similar in both matched and unmatched cases.

In the absence of a standardised coding for the three questions, the practices had developed their own protocols for recording the RCP3Q. This may mean that we missed or misinterpreted some coded responses, although we asked practices how they coded the data and customised our automated search accordingly (see Appendix 1, available online at www.thepcrj.org).

Practices invited patients to complete the ACQ after an asthma review in order to ensure that administration did not influence the patients' assessment of their control and how they answered the RCP3Q during the consultation. We specifically asked practice staff not to change their normal procedure for asking and recording the RCP3Q in order to reflect real-life practice, although awareness that they were participating in a study may have influenced their actions. In keeping with the concept of a phase IV study21 which aims to influence the ‘usual’ process as little as possible, we collected anonymous routinely recorded data from the practices. This meant that we are unsure how many ACQs were actually handed out, and cannot account for ACQs that we could not pair with RCP3Qs in the patients' electronic health record. Had we dictated procedures more tightly, we would probably have increased the rate of pairing but would not have been able to observe real-life practice.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Our data illustrate the importance of real-life validation of questionnaires. Compared with the study by Thomas et al. in which the RCP3Q was administered under research conditions,19 we observed similar sensitivity (RCP3Q extracted from the routine records detected 96% of patients with ACQ ≥1 compared with 94%) but specificity was halved (34% compared with 67%). This may reflect the explicit 1-week timescale applied in the research context compared with a relatively open-ended approach used to assess control in real life which would be more likely to capture a recent episode of poor control.

The observed heterogeneity between practices probably reflects procedural variations. Although some clinicians may administer the questions precisely as described in the literature, others may paraphrase the questions or introduce them informally into the conversation and record the answers at the end of the consultation. Some practices may adopt practical strategies such as sending out questionnaires some weeks in advance with an invitation to attend for a review (potentially misleading in a variable condition such as asthma). Clinicians will find pragmatic ways to administer questionnaires to people (often excluded in research studies) with poor literacy, reduced vision, or who ‘cannot answer a questionnaire in English’. The variation is further compounded when choice exists in coding systems. Similar variation in other disease contexts (e.g. the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire which assesses severity of depression22) raised concerns that the questionnaire performed inconsistently in real-life practice.23

Qualitative research after the PHQ9 was included in QOF in 2006 suggested that, despite general practitioners' caution about using formal questionnaires, patients' confidence in their general practitioners' assessment and management of their mental health problems increased.24 In contrast, the RCP3Q was generally well accepted by professionals in the pilot work,6 reflecting the emphasis — recently prioritised in the International Primary Care Respiratory Group's research needs prioritisation exercise — on simple questionnaires (or ‘questions’) to assist with clinical assessment in the typically low technological environment of primary care.25

Previous studies of the validity of the RCP3Q in the context of research concluded that ‘any positive responses may indicate suboptimal control’ whereas our findings suggest that the presence of daytime symptoms was compatible with good control as judged by an ACQ score of <0.75. This resonates with definitions of control in international and national guidelines which distinguish between occasional daytime symptoms (e.g. on ≤2 days a week) which may be ‘acceptable’ in a well-controlled patient whilst any nocturnal waking should be considered as less than well controlled and management adjusted accordingly.26,27 Modelling of similar morbidity questions in the context of a large-scale audit of asthma management concluded that the RCP3Q provided an effective assessment of control but that a version which incorporated frequency of symptoms was more sensitive to poor control.15

Including exacerbations and use of reliever inhalers as indicators of poor control added little to the predictive power of the RCP3Q in relation to the ACQ. This may be because both the questionnaires measure morbidity at one point in time whereas exacerbation and use of short-acting β2-agonists could reflect previous episodes of poor control which may have resolved at the time of a review. Exacerbations and prescribing history are normally readily available to primary care clinicians, and our data reinforce recommendations that all aspects of present control and future risk should be considered when assessing asthma control.1,3

Implications for future research, policy and practice

The clinical implications of our findings are summarised in Table 6. The RCP3Q scores have clinical utility although they should be interpreted in the light of the broader clinical context — especially scores of 1. Many developers of questionnaires express the hope that their instrument will be of value in the clinical context,9,28 and the potential of alternative instruments for measuring asthma control in routine asthma reviews has been summarised by the International Primary Care Respiratory Group.29 However, clinical utility is not the same as validation in a research context, and the significant variation we observed between practices emphasises the need for real-life phase IV assessment before tools are introduced into routine clinical practice.30 Provision of a single suitable coding system could remove one source of variability.

Conclusions

Our data support the promotion of the RCP3Q as a practical tool for detecting suboptimal current control when used in routine asthma reviews and offers advice on how scores obtained in real-life practice should be interpreted. Taken in conjunction with exacerbations and use of reliever inhalers, routine adoption of these simple morbidity questions could contribute to addressing the recognised challenge of improving asthma control.

References

Pinnock H, Fletcher M, Holmes S, et al. Setting the standard for routine asthma consultations: a discussion of the aims, process and outcomes of reviewing people with asthma in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:75–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00006

Haughney J, Price D, Kaplan A, et al. Achieving asthma control in practice: Understanding the reasons for poor control. Respir Med 2008;102:1681–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.08.003

Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Asthma Control and Exacerbations: Standardizing Endpoints for Clinical Asthma Trials and Clinical Practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:59–99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST

National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma Management Handbook 2006. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne, 2006.

Kiotseridis H, Bjermer L, Pilman E, Ställberg B, Romberg K, Tunsäter A . ALMA, a new tool for the management of asthma patients in clinical practice: development, validation and initial clinical findings. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21(2):139–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00091

NHS Confederation, British Medical Association. New GMS Contract 2003: investing in general practice. London, March 2003.

Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR . Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess 1998; Vol 2: No 14.

Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR . Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J 1999;14:902–07. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x

Juniper EF, Svensson K, Mork AC, Stahl E . Measurement properties and interpretation of three shortened versions of the asthma control questionnaire. Respir Med 2005;99:553–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2004.10.008

Juniper EF, Bousquet J, Abetz L, Bateman ED . Identifying ‘well-controlled’ and ‘not well-controlled’ asthma using the Asthma Control Questionnaire. Respir Med 2006;100:616–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.012

Pinnock H, Sheikh A, Juniper E . Concordance between supervised and postal administration of the MiniAQLQ and ACQ is very high. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:809–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.010

Pinnock H, Sheikh A, Juniper E . Evaluation of an intervention to improve successful completion of the Mini-AQLQ: comparison of postal and supervised completion. Prim Care Respir J 2004;13:36–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2003.11.004

Pearson MG, Bucknall CE, eds. Measuring clinical outcome in asthma: a patient-focused approach. London: Royal College of Physicians, 1999.

Georgiou A, Pearson M . Measuring outcomes with tools of proven feasibility and utility: the example of a patient-focused asthma measure. J Eval Clin Pract 2002;8:199–204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.2002.00346.x

Hoskins G, Williams B, Jackson C, Norman P, Donnan P . Assessing asthma control in UK primary care: use of routinely collected prospective observational consultation data to determine appropriateness of a variety of control assessment models. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-105

Jones KP, Bain DJG, Middleton M, Mullee MA . Correlates of asthma morbidity in primary care. BMJ 1992;304:361–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.304.6823.361

Jones KP, Charlton IH, Middleton M, Preece WJ, Hill AP . Targeting asthma care in general practice using a morbidity index. BMJ 1992;304:1353–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.304.6838.1353

Gruffydd-Jones K, Hollinghurst S, Ward S, Taylor G . Targeted routine asthma care in general using telephone triage. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:918–23.

Thomas M, Gruffydd-Jones K, Stonham C, Ward S, Macfarlane T . Assessing asthma control in routine clinical practice: use of the Royal College of Physicians ‘3 Questions’. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:83–8.

Campbell SM, Kontopantelis E, Hannon KL, Barber A, Burke M, Lester HE . Framework and indicator testing protocol for developing and piloting quality indicators for the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-85.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Maclntyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. London: Medical Research Council, 2008.

Mitchell C, Dwyer R, Hagan T, Mathers N . Impact of the QOF and the NICE guideline in the diagnosis and management of depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e279–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X572472

Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, et al. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. BMJ 2009;338:b750. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b750

Dowrick C, Leydon G, McBride A et al. Patients' and doctors' views on depression severity questionnaires incentivised in UK quality and outcomes framework: qualitative study. BMJ 2009;338:b663. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b663

Pinnock H, Ostrem A, Román Rodríguez M, et al. Prioritising the respiratory research needs of primary care: the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) e-Delphi exercise. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21(1):19–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00006

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2007. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org

British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Thorax 2008;63(Suppl 4):1–121. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk and http://www.sign.ac.uk

Jones P, Harding G, Wiklund I, Berry P, Leidy N . Improving the process and outcome of care in COPD: development of a standardised assessment tool. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:208–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00053

International Primary Care Respiratory Group. The IPCRG users' guide to currently available asthma control tools. Available from: http://www.theipcrg.org/display/RESAST/Asthma+Control.

Pinnock H, Lester H . A question of quality? A single questionnaire for measuring asthma control, structuring asthma reviews, and monitoring health service standards. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21(2):122–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00030

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Niels Chavannes

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Funding This UK Respiratory Research Foundation funded study was made possible by a grant from the Primary Care Respiratory Society-UK. HP and CB are supported by Primary Care Research Career Awards from the Chief Scientist's Office of the Scottish Government. GH was also a recipient of a CSO Primary Care Research Career Award during the life of the project and continues to be supported by a CSO fellowship.

We are grateful to the officers of the Primary Care Research Networks in supporting practice recruitment and to the practices, practice nurses and administrative staff for their active participation, and the patients who gave their time to participate in the trial. Elizabeth Maxwell provided administrative support for the questionnaire data entry and Matt Ball and Stanley Musgrave from Optimum Patient Care undertook the computer data extraction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HP initiated the idea for the study in discussion with DP, GH, HL and SC and led the development of the protocol, securing of funding, study administration, data analysis, interpretation of results, and writing of the paper. HL, SC, DK, KG-J, DP, GH and CB were grant holders who contributed to the development of the protocol. DP also contributed to securing funding and study administration. SC and KH contributed to practice recruitment and support. CB undertook the statistical analysis. HP and CB wrote the initial draft of the paper. All authors had full access to all the data and were involved in interpretation of the data and writing of the paper. HP is the study guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

At the time this study was conducted, SC and HL were contracted to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to provide advice on removal of indicators and pilot new indicators for the Quality and Outcomes Framework. The views expressed are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of NICE or its independent Quality and Outcomes Framework advisory committee. HP is an Associate Editor of the PCRJ, but was not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish, this article.

Appendix 1 Coding conventions for the RCP3Qs in the participating practices

Appendix 1 Coding conventions for the RCP3Qs in the participating practices

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinnock, H., Burton, C., Campbell, S. et al. Clinical implications of the Royal College of Physicians three questions in routine asthma care: a real-life validation study. Prim Care Respir J 21, 288–294 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00052

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00052

This article is cited by

-

IMPlementing IMProved Asthma self-management as RouTine (IMP2ART) in primary care: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled implementation trial

Trials (2023)

-

A systematic review of questionnaires measuring asthma control in children in a primary care population

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2023)

-

Home monitoring with connected mobile devices for asthma attack prediction with machine learning

Scientific Data (2023)

-

Post hoc analysis of initial treatments and control status in the INITIAL study: an observational study of newly diagnosed patients with asthma

BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2020)

-

Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Greek version of the Active Life with Asthma (Gr-ALMA) review: a descriptive methodological study

BMC Health Services Research (2019)