Abstract

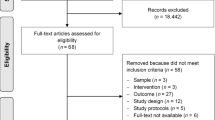

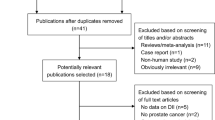

Lycopene has a chemopreventive effect against prostate cancer but its role in prostate cancer progression is unknown; many patients increase their intake of lycopene, although there are no evidence-based guidelines to suggest an effect. Our objective was to conduct a systematic review of literature to evaluate the association between lycopene intake and prostate cancer progression. MEDLINE, EMBASE CINAHL Plus, Web of Science, AMED and CENTRAL databases were systematically searched using terms for lycopene and prostate cancer progression to identify studies published before January 2009. Eight intervention studies were identified (five with no control group; one with an unmatched control group; and two randomized controlled trials (RCTs)). An inverse association was observed between lycopene intake and PSA levels in six studies. The rates of progression measured by bone scan in one RCT were lower in the intervention group. Lycopene resulted in lowering cancer-related symptoms (pain, urinary tract symptoms), and severe toxicity or intolerance was not evident. However, the evidence available to date is insufficient to draw a firm conclusion with respect to lycopene supplementation in prostate cancer patients and larger RCTs are required in broader patient groups.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Oh WK, Small EJ . Complementary and alternative therapies in prostate cancer. Semin Oncol 2002; 29: 575–584.

Eng J, Ramsum D, Verhoef M, Guns E, Davison J, Gallagher R . A population-based survey of complementary and alternative medicine use in men recently diagnosed with prostate cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 2003; 2: 16.

Wilkinson S, Gomella LG, Smith JA, Brawer MK, Dawson NA, Wajsman Z et al. Attitudes and use of complementary medicine in men with prostate cancer. J Urol 2002; 168: 2505–2509.

Chan JM, Elkin EP, Silva SJ, Broering JM, Latini DM, Carroll PR . Total and specific complementary and alternative medicine use in a large cohort of men with prostate cancer. Urology 2005; 66: 1223–1228.

Wiygul JB, Evans BR, Peterson BL, Polascik TJ, Walther PJ, Robertson CN et al. Supplement use among men with prostate cancer. Urology 2005; 66: 161–166.

Ponholzer A, Struhul G, Maderbacher S . Frequent use of complementary medicine by prostate cancer patients. Eur Urol 2003; 43: 604–608.

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL . Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 246–252.

WCRF-AICR. Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: Global perspective. 2007. AICR: Washington DC.

Vinceti M, Wei ET, Malagoli C, Bergomi M, Vivoli G . Adverse health effects of selenium in humans. Rev Environ Health 2001; 16: 233–251.

Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Kana W, Graham AC, Walter CW, Giovannucci EL . Zinc supplement use and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95: 1004–1007.

Giovannucci E . Tomatoes, tomato-based products, lycopene, and cancer: review of the epidemiologic literature. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 317–331.

Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC . Intake of carotenoids and retinol in relation to risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995; 87: 1767–1776.

Wu K, Erdman JW, Schwartz SJ, Platz EA, Leitzmann M, Clinton SK et al. Plasma and dietary carotenoids, and the risk of prostate cancer: a nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13: 260–269.

Bertram JS . Carotenoids and gene regulation. Nutr Rev 1999; 57: 182–191.

Amir H, Karas M, Giat J, Danilenko M, Levy R, Yermiahu T et al. Lycopene and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 cooperate in the inhibition of cell cycle progression and induction of differentiation in HL-60 leukemic cells. Nutr Cancer 1999; 33: 105–112.

Levy J, Bosin E, Feldman B, Giat Y, Miinster A, Danilenko M et al. Lycopene is a more potent inhibitor of human cancer cell proliferation than either alpha-carotene or beta-carotene. Nutr Cancer 1995; 24: 257–266.

Karas M, Amir H, Fishman D, Danilenko M, Segal S, Nahum A et al. Lycopene interferes with cell cycle progression and insulin-like growth factor I signaling in mammary cancer cells. Nutr Cancer 2000; 36: 101–111.

Bertram JS, Pung A, Churley M, Kappock TJI, Wilkins LR, Cooney RV . Diverse carotenoids protect against chemically induced neoplastic transformation. Carcinogenesis 1991; 12: 671–678.

Zhang L, Cooney RV, Bertram JS . Carotenoids up-regulate connexin43 gene expression independent of their provitamin A or antioxidant properties. Cancer Res 1992; 52: 5707–5712.

Rao AV, Fleshner N, Agarwal S . Serum and tissue lycopene and biomarkers of oxidation in prostate cancer patients: a case-control study. Nutr Cancer 1999; 33: 159–164.

Riso P, Pinder A, Santangelo A, Porrini M . Does tomato consumption effectively increase the resistance of lymphocyte DNA to oxidative damage? Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69: 712–718.

Syed DN, Khan N, Afaq F, Mukhtar H . Chemoprevention of prostate cancer through dietary agents: progress and promise. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16: 2193–2203.

Lieberman R, Bermejo C, Akaza H, Greenwald P, Fair W, Thompson I . Progress in prostate cancer chemoprevention: modulators of promotion and progression. Urology 2001; 58: 835–842.

Chan JM, Holick CN, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL . Diet after diagnosis and the risk of prostate cancer progression, recurrence and death (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2006; 17: 199–208.

Van Petter CL, de Boer JC, Tomlinson Guns ES . Diet and dietary supplement intervention trials for the prevention of prostate cancer recurrence: a review of the randomized controlled trial evidence. J Urology 2008; 180: 2314–2322.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996; 17: 1–12.

Kucuk O, Sarkar FH, Djuric Z, Sakr W, Pollak MN, Khachik F et al. Effects of lycopene supplementation in patients with localized prostate cancer. Exp Biol Med 2002; 227: 881–885.

Kucuk O, Sarkar FH, Sakr W, Khachik F, Djuric Z, Banerjee M et al. Lycopene in the treatment of prostate cancer. Pure Appl Chem 2002; 74: 1443–1450.

Bowen P, Chen L, Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis M, Duncan C, Sharifi R, Ghosh L et al. Tomato sauce supplementation and prostate cancer: Lycopene accumulation and modulation of biomarkers of carcinogenesis. Exp Biol Med 2002; 227: 886–893.

Ansari MS, Gupta NP . Lycopene: a novel drug therapy in hormone refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 2004; 22: 415–420.

Barber NJ, Zhang X, Zhu G, Pramanik R, Barber JA, Martin FL et al. Lycopene inhibits DNA synthesis in primary prostate epithelial cells in vitro and its administration is associated with a reduced prostate-specific antigen velocity in a phase II clinical study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2006; 9: 407–413.

Chen L, Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis M, Duncan C, Sharifi R, Ghosh L, van Breemen R et al. Oxidative DNA damage in prostate cancer patients consuming tomato sauce-based entrees as a whole-food intervention. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 1872–1879.

Jatoi A, Burch P, Hillman D, Vanyo JM, Dakhil S, Nikcevich D et al. A tomato-based, lycopene-containing intervention for androgen-independent prostate cancer: results of a Phase II Study from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Urology 2007; 69: 289–294.

Clark PE, Hall MC, Borden Jr LS, Miller AA, Hu JJ, Lee WR et al. Phase I-II prospective dose-escalating trial of lycopene in patients with biochemical relapse of prostate cancer after definitive local therapy. Urology 2006; 67: 1257–1261.

Kim HS, Bowen P, Chen L, Duncan C, Ghosh L, Sharifi R et al. Effects of tomato sauce consumption on apoptotic cell death in prostate benign hyperplasia and carcinoma. Nutr Cancer 2003; 47: 40–47.

Kucuk O, Sarkar FH, Sakr W, Djuric Z, Pollak MN, Khachik F et al. Phase II randomized clinical trial of lycopene supplementation before radical prostatectomy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001; 10: 861–868.

Ansari MS, Gupta NP . A comparison of lycopene and orchidectomy vs orchidectomy alone in the management of advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int 2003; 92: 375–378.

National Cancer Institute. Common Toxicity Criteria Manual. Version 2 1999. NIH: Maryland, USA.

Abbas F, Scardino PT . The natural history of clinical prostate carcinoma. Cancer 1997; 80: 827–833.

van Weerden WM, Schröder FH . The use of PSA as biomarker in nutritional intervention studies of prostate cancer. Chem Biol Interact 2008; 171: 204–211.

Stahl W, Schwarz W, Sundquist AR, Sies H . cis-trans isomers of lycopene and beta-carotene in human serum and tissues. Arch Biochem Biophys 1992; 294: 173–177.

Kanagaraj P, Vijayababu MR, Ravisankar B, Anbalagan J, Aruldhas MM, Arunakaran J . Effect of lycopene on insulin-like growth factor-I, IGF binding protein-3 and IGF type-I receptor in prostate cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2007; 133: 351–359.

Schmitz HH, Poor CL, Wellman RB, Erdman Jr JW . Concentrations of selected carotenoids and vitamin A in human liver, kidney and lung tissue. J Nutr 1991; 121: 1613–1621.

Clinton SK, Emenhiser C, Schwartz SJ, Bostwick DG, Williams AW, Moore BJ et al. Cis-trans lycopene isomers, carotenoids, and retinol in the human prostate. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996; 5: 823–833.

Parker RS . Carotenoid and tocopherol composition of human adipose tissue. Am J Clin Nutr 1988; 47: 33–36.

Ripple MO, Henry WF, Rago RP, Wilding G . Prooxidant-antioxidant shift induced by androgen treatment of human prostate carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997; 89: 40–48.

Malins DC, Polissar NL, Gunselman SJ . Models of DNA structure achieve almost perfect discrimination between normal prostate, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and adenocarcinoma and have a high potential for predicting BPH and prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94: 259–264.

Stahl W, Sies H . Lycopene: a biologically important carotenoid for humans? Arch Biochem Biophys 1996; 336: 1–9.

Bankson DD, Countryman CJ, Collins SJ . Potentiation of the retinoic acid-induced differentiation of HL-60 cells by lycopene. Am J Clin Nutr 1991; 53 (Suppl): 13.

Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Shidoji Y, Nishiwaki S, Yamada T, Moriwaki H, Muto Y . Suppression by carotenoids of microcystin-induced morphological changes in mouse hepatocytes. Lipids 1995; 30: 1029–1034.

Mellert W, Deckardt K, Gembardt C, Schulte S, Van Ravenzwaay B, Slesinski RS . Thirteen-week oral toxicity study of synthetic lycopene products in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2002; 40: 1581–1588.

Christian M S, Schulte S, Hellwig J . Developmental (embryo-fetal toxicity/teratogenicity) toxicity studies of synthetic crystalline lycopene in rats and rabbits. Food Chem Toxicol 2003; 41: 773–783.

Tonucci LH, Holden JM, Beecher GR, Khachik F, Davis CS, Mulokozi G . Carotenoid content of thermally processed tomato-based food products. J Agric Food Chem 1992; 43: 579–586.

Stahl W, Sies H . Uptake of lycopene and its geometrical isomers is greater from heat-processed than from unprocessed tomato juice in humans. J Nutr 1992; 122: 2161–2166.

Gartner C, Stahl W, Sies H . Lycopene is more bioavailable from tomato paste than from fresh tomatoes. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 66: 122.

Paetau I, Khachik F, Brown ED, Beecher GR, Kramer TR, Chittams J et al. Chronic ingestion of lycopene-rich tomato juice or lycopene supplements significantly increases plasma concentrations of lycopene and related tomato carotenoids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1998; 68: 1187–1195.

Rao AV, Agarwal S . Bioavailability and in vivo antioxidant properties of lycopene from tomato products and their possible role in the prevention of cancer. Nutr Cancer 1998; 31: 199–203.

Boileau TW, Liao Z, Kim S, Lemeshow S, Erdman Jr JW, Clinton SK . Prostate carcinogenesis in N-methyl-N-nitrosourea(NMU)-testosterone-treated rats fed tomato powder, lycopene or energy-restricted diets. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95: 1578–1586.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Ms Alex McIlroy for her assistance in developing the electronic search strategy used in the systematic review and Ms Helen Mulholland for her support in selecting the relevant articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haseen, F., Cantwell, M., O'Sullivan, J. et al. Is there a benefit from lycopene supplementation in men with prostate cancer? A systematic review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 12, 325–332 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2009.38

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2009.38

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Increased dietary and circulating lycopene are associated with reduced prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2017)

-

Prostate cancer progression and mortality: a review of diet and lifestyle factors

World Journal of Urology (2017)

-

Future directions in the prevention of prostate cancer

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2014)

-

Prostatakarzinomprophylaxe durch Nahrungsergänzungsmittel

Der Urologe (2014)

-

Effect of carotenoid supplementation on plasma carotenoids, inflammation and visual development in preterm infants

Journal of Perinatology (2012)