Abstract

Only recently, the broad research program of embodied cognition has fuelled a substantial and ongoing body of research at the crossroads of cognitive science and film studies. Two influential theories of embodiment that have received considerable attention among film scholars are: Conceptual Metaphor Theory (originated in the field of cognitive linguistics) and Embodied Simulation Theory (originated in the field of neuroscience). Despite their intimate relationship, both theories have been rarely addressed together in the context of film studies. This article takes on the challenge of combining both perspectives into a unified embodied model for understanding conceptual meaning in cinema. The study is driven by two key assumptions, namely: (1) that meaning in film is metaphorically mapped within our sensory-motor system and (2) that embodied simulation processes in the brain allow for the viewer to infer this meaning from the evidence provided by the film. To clarify both assumptions, the article will present a discussion of the theme of embodiment at three levels of analysis: the conceptual level (how is meaning embodied in the human mind?), the formal level (how is this meaning structured in the visual mode of expression?) and the receptive level (how is the viewer able to infer this meaning on the basis of the evidence provided by the form?). The grounding problem of fictional subjectivity in cinema (that is, how are viewers able to attribute mental states to fictional characters in films?) will be used to test the validity of both claims.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past three decades, various strands of cognitive science (linguistics, psychology, philosophy, neuroscience, anthropology) have embraced the thesis of “embodiment”. Central to this thesis is the idea that cognition is not simply a computational process, but a biological phenomenon with a firm grounding in bodily, social and cultural experience. In conjunction with this theoretical shift, cognitive film scholars have been increasingly adopting some of the newly introduced concepts of this framework to shed new light on the creative and receptive aspects of cinema. Two major theories in particular have attracted considerable attention in recent years: George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s Conceptual Metaphor Theory (henceforth, CMT) and Vittorio Gallese’s Embodied Simulation Theory (henceforth, EST). CMT proposed a theory of embodiment according to which humans reason about abstract concepts in terms of concrete concepts by a process of “metaphorical mapping” (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, 1999). EST introduced a theory of embodiment according to which individuals, aided by a common neurological mapping (the so-called “mirror-neuron system”), make use of their own mental states or processes in functionally attributing them to others (Gallese, 2009, 2011a, b; Gallese and Sinigaglia, 2011). As literature indicates, both accounts have fuelled a substantial and ongoing body of research at the crossroads of cognitive linguistics and film studies, on the one hand (for example, Buckland, 2000; Branigan, 2006; Forceville and Jeulink, 2011; Kappelhoff and Müller, 2011; Ortiz, 2011; Forceville and Renkens, 2013; Winter, 2014; Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2014a, 2015a; Bálint and Tan, 2015; Fahlenbrach, 2016), and neuroscience and film studies, on the other hand (for example, Hasson et al., 2008; Grodal, 2009; Gallese and Guerra, 2012, 2015; D’Aloia and Eugeni, 2014; Heimann et al., 2014, 2016; D’Aloia, 2015; Ward, 2015; Lankinen et al., 2016). Despite the intimate relationship between metaphor interpretation and embodied simulation (ES) (for example, Gallese and Lakoff, 2005; Gibbs, 2006), both theories have been rarely addressed together in the context of film studies. This article takes on the challenge of combining both perspectives into a coherent embodied theoretical framework for understanding meaning-making in film. To structure this exercise in interdisciplinarity, we appeal to the inferential model of communication, as originally advocated by Paul Grice (1989) and further elaborated by Wilson and Sperber (2012). This model offers not only a coherent theoretical narrative that is general enough for us to map both theories, but also a narrative that connects up most fittingly with the embodied view. First, there is the anchor point of “manifestness” or “derivativeness” (see also Searle, 1998: 141). The inferential model of communication proposes a model of communication according to which modes of expressions (for example, languages, films) are not merely conceived as code systems, but foremost as providers of evidence (that is, manifestations) of an underlying thought (Wilson and Sperber, 2012: 2).Footnote 1 Second, there is the anchor point of “mind reading” (Wilson and Sperber, 2012: 233). Inferential comprehension sees both communicator and audience as deeply involved in a process of mind-reading in which the recipient infers the underlying thought from the evidence directly provided by the formal expression.2 Both anchor points allow us to unify both theories in one embodied model of communication that can be best summarized in the following dense manner:

-

(1) Humans (for example, artists) have the intention to convey thought to others. This thought is embodied. Conceptual metaphor exemplifies one kind of cognitive mechanism through which this principle of embodied cognition operates.

-

(2) Meaning is a form of derived embodied thought. Modes of expressions (for example, language, cinema) are meaningful insofar they provide evidence of this underlying embodied thought (1) (for example, insofar films offer manifestations of conceptual metaphors).

-

(3) Comprehension occurs when a perceiver (for example, film viewer) infers this underlying embodied thought (1), as embodied in the mode of expression (2). This mind-reading is facilitated by ES processes in the perceiver.

Each of the three premises above considers a corresponding set of theoretical concepts, questions and challenges that is central to the apprehension of our argument. The first assumption involves an inquiry into the concept of embodied cognition. It explores, among other questions, how thought is grounded in perception (Barsalou, 1999, 2008) and how abstract concepts are metaphorically structured in terms of concrete concepts (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, 1999). The second assumption underlies the question of how thought, as conceptually embodied, can be manifested in a perceptual form or mode of expression. It involves such questions as to how the same conceptual metaphors, as identified in language, may be transferred to images (see also Forceville, 2009). As we shall see, the nature of this task, which challenges the discrimination between vision and thinking, is intimately connected to the pioneering work of Rudolf Arnheim (1954, 1969). Last, the third assumption involves the question of how this embodied meaning, as manifested in a perceptible form, can be inferred by the perceiver of the form on the basis of his or her neurological embodiment. As stated, this question primarily relates to Gallese’s work on ES. As can be seen, each premise takes the notion of embodiment to a different level. The first premise discusses the theme at the level of concepts, the second one, at the level of form, and the third one, at the level of the recipient of the form. The higher levels are only accessible if the previous ones are satisfied. For instance, one can only address the question of how meaning is embodied at the formal level, if this meaning has an embodied structure at the conceptual level. Similarly, one can only examine how meaning in a mode of expression triggers a simulation process in the viewer, if the preceding condition of embodied meaning at the formal level is satisfied.

The first theoretical section of the article is organized in such a way as to mirror this three-part structure. Thereby much attention will be given to the middle part, in particular to the challenge of translating the complexity of conceptual metaphor at the cognitive level to the context of visual form. In the second application part of our article, we will test the rigidity of our argument by considering it as a solution to the grounding problem of two abstract categories of fictional subjectivity in film, namely visual perception and emotions. This problem can be situated on the intersection of theory of mind and narrative comprehension (for example, Palmer, 2004; Zunshine, 2006; Bernaerts et al., 2013), and involves the question of how viewers are able to attribute mental states to fictional characters in cinema.

Theorizing embodiment

From standard cognitive science to embodied cognition

The task of characterizing the concept of embodied cognition often amounts to a comparative study of the way the discipline of cognitive science has evolved from a standard disembodied take on mind and reason, as established in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, to a principally embodied one, as the view became prominent (again) in the 1980s and onwards.Footnote 2 Subsequently, a characterization of embodied cognition arises largely from a description of the problems involved in its counterpart, standard cognitive science, as well as a description of the way the notion of embodiment has been proposed to offer a solution to these problems. Broadly speaking, the umbrella term of “standard” or “first-generation” cognitive science refers to a view of cognition according to which the functions of thought and reason are represented by formal abstract models (for example, Fodor, 1975, 1983). In these systems the workings of the functional relations of the mind are described in analogy to the formal logic of a digital computer. On this computational view of the mind, which can be attributed primarily to generative linguistics, information processing psychology and classical artificial intelligence, cognition is studied in isolation from the body and the physical, cultural and social world in which it thrives (see also Lakoff and Johnson, 1999: 75; Gallese and Lakoff, 2005: 456). To look at its underlying stages more closely, let us consider Fig. 1.

In the first stage, human sensory-motor experiences with the physical world give rise to the neural activation of perceptual states. In the second stage a subset of these perceptual states are transduced into a completely new representation language, what Barsalou (1999: 578) refers to as the “amodal symbol system”. The system is called amodal because it is inherently non-perceptual. It involves larger representational structures such as feature lists, frames, schemata, semantic networks and production systems, that do not bear any correspondence to the perceptual states that produced them. It is here that we can see an analogy to language. As Barsalou (1999: 578) writes: “Similarly to how words typically have arbitrary relations to entities in the world, amodal symbols have arbitrary relations to perceptual states. Just as the word ‘chair’ has no systematic similarity to physical chairs, the amodal symbol for chair has no systematic similarity to perceived chairs”. In the third stage, then, these abstract, disembodied structures are retracted in support of all the higher cognitive functions, including knowledge and thought.

As Barsalou (1999: 580) and others have emphasized, the computational theory of mind faces many unresolved questions. In addition to the lack of empirical evidence (“do amodal symbols exist?”), there is the transduction problem (“if they exist, how then, are the perceptual states mapped into amodal symbols?”), and its reverse, the symbol grounding problem (how are amodal symbols grounded in perception?). As a way to illustrate the latter problem, authors typically refer to John Searle’s (1980) famous “Chinese Room Argument” (see also Searle, 2004: 62; Shapiro, 2011: 95). Searle has constructed this thought experiment with the purpose of showing how the mental world cannot be compared with the workings of a computer program, no matter how complex and sophisticated it is. The author invites us to imagine a room, the so called “Chinese room”, in which an English speaker (let’s say John Searle himself), who has no understanding of the Chinese language, is contained. Inside the room, John has an instruction manual in English that tells him systematically which symbols he has to write down in response to the Chinese characters that he is receiving through the slot of the room. From the viewpoint of a person outside the room with a genuine understanding of the Chinese language the symbols that John is receiving are questions in Chinese and the symbols he is sending out are apt responses to these questions. To the Chinese speaker John appears to understand Chinese. Yet, to us, the reader who is aware of the experiment, John does not understand Chinese. What occurs inside the room is simply the manipulation of symbols according to their “syntax”. Actual understanding, however, involves semantics, knowing what these symbols stand for or mean. The bottom line of the experiment is that symbols do not acquire meaning simply in virtue of bearing relationships to other symbols. It demonstrates, to cite Glenberg and Robertson (2000: 381), “that abstract, arbitrary symbols, such as words, need to be grounded in something other than relations to more abstract arbitrary symbols if any of those symbols are to be meaningful”.

It is in specifying this “something other” that “second-generation” cognitive science, or the cognitive science of the “embodied mind” comes in (see also Shapiro, 2011: 91). The theme of embodiment is vast and complex, covering many interpretations and variations (see, for example, Wilson, 2002; Shapiro, 2011). Nevertheless, there seems to be a general consensus among cognitive scientists of different strands as to its basic claim, the assertion that the human cognitive system does not so much involve a disembodied Cartesian mind manipulating symbols according to rules, but a mind that is based upon human interaction with the physical, social and cultural dimensions of the world around us. Embodiment thus comprises both a sensory-motor aspect as well as a cultural one. Various accounts of embodiment emphasize, to greater and lesser extent, this coexistence of body and culture. On a more general note one can say that cognitive anthropologists have a tendency to stress the cultural dimension of embodiment, whereas cognitive neuroscientists and psychologists commonly emphasize its bodily dimension (see also Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2015a: 22–25). Two influential approaches of embodiment that authors frequently appeal to for illustrating the bodily dimension of cognition, are Lawrence Barsalou’s (1999) account of “perceptual symbols” and Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980, 1999) account of “conceptual metaphors”. For sake of clarity and comparison, we will illustrate both theories and their intersection by contrasting standard cognitive science, as schematically represented in Fig. 1, with the visual representation of embodied cognition, as sketched out in Fig. 2.

As with amodal symbol systems, perceptual states arise in sensory-motor systems. However, the crucial difference with Fig. 1 lies in the second stage. Rather than transducing a subset of a perceptual state into a completely new representational language, a “perceptual symbol system”, as Barsalou (1999: 578) calls it, extracts a subset of a perceptual state and stores it for later use as a symbol. In contrast to amodal symbols, perceptual symbols are not arbitrary, but modal and analogical. They are modal because they are represented in the same systems as the perceptual states that produced them. On this view, perception and cognition are not two independent systems. Instead, both systems share a common representational system. Because perceptual symbols are modal, they are also analogical. The structure of a perceptual symbol corresponds, at least somewhat, to the perceptual state that produced it. It is here, against the background of what Barsalou calls an “analogue model symbol”, that one can also consider Lakoff and Johnson’s notion of an “image schema” (Johnson, 1987; Lakoff, 1987). Image schemas are recurring, highly schematic dynamic structures, which arise from, or are grounded in, human sensory-motor experience (Hampe, 2005: 1). They include such basic orientational schemas as FRONT-BACK, LEFT-RIGHT, TOP-DOWN, IN-OUT, and so on. They are often referred to as “basic” concepts in that they derive directly from recurring dynamic patterns of sensory-motor interactions in a physical world. For instance, we come to understand the basic distinction between “in” and “out” simply in virtue of our bodily interaction with all sorts of bounded regions (for example, rooms, vehicles, clothes, and so on) (Johnson, 1987: 21). Likewise, the SOURCE-PATH-GOAL schema is grounded in our experience of physically moving from one location to another. These basic structures salient in most of our everyday experiences, then, can be extended and elaborated metaphorically, as Johnson (1987: 34) argues, to connect up different aspects of conceptual meaning. For instance, we project the physical logic of CONTAINMENT onto such non-spatial entities as story events (“Tell me your story again, but leave out the minor details”), visual fields (“I have him in sight”), and agreements (“Don’t you dare back out of our agreement”), and so on. It is here that Lakoff and Johnson’s influential concept of “conceptual metaphor” comes into prominence. Cognitive linguistics, the discipline in which the concept originated in the early 1980s, maintains the view according to which thought is “largely metaphorical, making use of the same sensory-motor system that runs the body” (Lakoff, 2003: 3).4 The basic idea is that metaphor is not simply a rhetorical, linguistic device, but a cognitive tool that allows humans to reuse their resources of bodily experience (that is, source domains) to reason about more abstract and less defined concepts (that is, target domains). From this perspective, the various linguistic expressions (for example, “The deadline is approaching”, “Time flies by”) are merely the surface manifestations of an underlying conceptual metaphor (for example, TIME IS SPACE).Footnote 3

From linguistic meaning to embodied meaning

Having considered how the world of thought is embodied, we can now move outside the mental realm by considering how this meaning relates to the level of form or mode of expression. Following a similar structure as the previous section, we will discuss this question by opposing two views of meaning: the conceptual or propositional view and the embodied view. Likewise, we will illuminate the latter model by contrasting it with the former one.

The conceptual or propositional theory of meaning, as Mark Johnson (2007: 8, 2013: 21) calls it, assumes that meaning in all modes of expressions (including the visual arts) is essentially linguistic in nature. Underlying this view is a line of reasoning, anchored in standard cognitive science, which can be best summarized as follows:

-

(1) Form is considered meaningful insofar it prompts the perceiver of the form to infer thought.

-

(2) According to the standard view of cognition, thought is characterized by disembodied formal symbols.

-

(3) Disembodied formal symbols share a structure that is similar to language (that is, the “language of thought” hypothesis).

-

(4) Therefore, meaning in form is regarded solely as a property of language.

-

(5) If other non-verbal modes of expression such as music or the visual arts have any meaning it can only be via structures similar to language.

On this reductionist view, the meaning of the formal expression (for example, a linguistic expression, a work of art) is reduced to sentence meaning. It entails that to infer the meaning of the formal expression one does not have to rely on psychological content (for example, intentions) or on the way the mind is embodied. After all, both thought and mode of expression share a structure that is like language. Therefore, it is sufficient to consider the arbitrary linguistic codes and conventions of the expression to infer the meaning of the expression. In film studies this idea is perhaps best exemplified in the work of film theorist Christian Metz (1974). Influenced by Saussurean structuralism, he proposed the idea that film can be studied as a form of linguistic discourse (that is, the “film-as-language” hypothesis).

By contrast, the embodied view of meaning, as forwarded by Mark Johnson (2007, 2013), proposes a somewhat different approach to meaning. On this view, formal expressions are foremost manifestations of an underlying cognitive process of meaning-making that is grounded in bodily knowledge. Underlying this view is a line of reasoning, anchored in embodied cognitive science, which can be put as follows:

-

(1) Form is considered meaningful insofar it prompts the perceiver of the form to infer thought.

-

(2) According to the embodied view of cognition thought is grounded in embodiment.

-

(3) Therefore, meaning in form is regarded as a property of embodied thought. Form provides the perceiver of the form with evidence of this underlying process of embodied meaning-making.

-

(4) Language constitutes only one mode of evidence by virtue of which these embodied processes appeal to human senses.

-

(5) Therefore, meaning is not restricted to linguistic meaning.

By considering formal expressions as vehicles for conveying embodied thought, the embodied view of meaning assumes a distinction which is absent from the classical view of meaning where both the meaning at the conceptual level and the meaning at the formal level conjoin on the basis of their matching linguistic structure (conceptual meaning=linguistic meaning). Consequently, because this approach does not equate the meaning of a formal expression with linguistic meaning, but with the embodied thought underlying it, thereby considering the latter instead as evidence for the former (thus separating both), the embodied view logically opens itself up to a relation between two distinctive questions of embodiment:

-

(1) How is thought embodied at the conceptual level?

-

(2) How is this thought, embodied at the conceptual level, embodied at the formal level? (for example, How does conceptual metaphor manifests itself in form?)

We have already addressed the first question in the previous section of our article. The second question, however, requires a further elaboration of the relation between form (the domain of perception) and content (the domain of thought). More generally, we can distinguish here between two general categories of form in which the embodiment of concepts may appeal to us, namely the category of form that is solely or primarily verbal in nature (for example, language) and the category of form that is solely or primarily non-verbal in nature (for example, film). The first category has been studied most systematically in the discipline of cognitive linguistics. It involves, among others, the study of how conceptual metaphors are manifested linguistically and how image schemas are extended metaphorically to structure abstract concepts in language. Studies can be found on many concepts ranging from time (for example, Lakoff and Johnson, 1980,1999; Boroditsky, 2000; Gentner, 2001; Gentner et al., 2002; Evans, 2003; Núñez and Sweetser, 2006) and emotions (for example, Kövecses, 2000) to mental faculties such as seeing (for example, Lakoff, 1995; Yamanashi, 2010) and thinking (for example, Lakoff and Johnson, 1999: 393–399; Yu, 2003, 2004; Gibbs, 2005: 97; Johnson, 2007: 165). Over the years, however, this one-sided emphasis on linguistic manifestations has been criticized. For instance, some scholars have warned CMT for the danger of circular reasoning, the fallacy that CMT attempts to demonstrate the conceptual nature of metaphor (their central claim) solely by considering linguistic concepts (see also Gibbs and Perlman, 2006; Forceville, 2009; Forceville and Jeulink, 2011; Pecher et al., 2011).

Consequently, to overcome this fallacy, researchers have to broaden the debate from simply considering how embodied metaphors underlie linguistic expressions, to examining how they also underlie meaning in other forms of expression. It is here that the importance of the second category of non-verbal form comes into play. Indeed, if metaphor operates independently of form or mode of expression, as Lakoff and Johnson claim, then it is vital to demonstrate that meaning in the visual arts is structured in the same embodied and metaphorical way as meaning in language (see also Johnson, 2007; Forceville, 2009: 212). In examining the validity of this hypothesis, however, scholars are confronted with the challenge of addressing the ontological difference between words and images, or in the light of this article, between language and film. As repeatedly pointed out in literature, both modes of expression are significantly dissimilar, having both a distinctive reality status (for example, Gaut, 2010: 52; Grodal, 2016). Language is characterized by a formal and symbolic structure that bears no relation to the salience of the first-order world of perception. It is precisely this breach with reality that makes language such a popular field for the study of metaphor. Because language has a nature that resembles somehow the conceptual nature of the mind, the former is capable of labelling the concepts of the latter (including the concepts of metaphor) directly and unambiguously (for example, one can recall the abstract concept of emotion simply by the word “emotion”). Film, by contrast, does not share this holistic and analytic nature of language. Instead, it has a nature that to an extent resembles the reality it represents. Precisely because of its ontological disanalogy to language, film is encountered with a conceptual concern that at first sight seems to impede a metaphorical analysis of the medium (see also Grodal, 2016). This concern amounts to a problem which can be articulated as follows: if conceptual metaphor involves a mapping between two different conceptual domains, and film, due to its phenomenological concreteness and lack of generality does not exist of concepts, how is it possible then, that film, like language, can exhibit the property of expressing conceptual metaphors? If the medium of film wishes to overcome this problem, it, therefore, has to exhibit a capacity that resembles somehow the abstract-analytic ability of language and mind (that is, the ability of imposing a structure onto the first-order world of human perception). The task, then, is to identify something that can impose such a structure. In other words, how can visual images, despite their concrete nature, elicit such abstractness?

A pioneering answer to this question has been proposed by the famous film theorist and perceptual psychologist Rudolf Arnheim (1954, 1969). Arnheim systematically challenged the dualistic view of meaning according to which images of art (the domain of visual perception) cannot exhibit concepts (the domain of thought). According to him, the visual arts offer more than merely illustrations of events or things. They are a homeground of what he calls “visual thinking” (Arnheim, 1969: 254). For Arnheim (1969: 271) works of visual art are the “strongest, purest, most precise embodiment of the meaning that, consciously or unconsciously, he [the artist] intends to convey”. To trace visual thinking in the images of art, Arnheim (1969: 255) argues, one must look for “well-structured shapes and relations”, for it is through these “abstract patterns” that the “concepts or the central thought of the work” are spelled out. He illustrates his point by discussing numerous examples: from thinking in children’s drawings to abstract patterns in visual art. One can find an illuminating example of the latter in his comparison of Camille Corot’s figurative painting Mother and Child on the Beach and Henry Moore’s non-figurative sculpture Two Forms (Arnheim, 1969: 271–273) (see Fig. 3).

Camille Corot’s Mother and Child on the Beach (a) (John G. Johnson collection, Cat, 930, Philadelphia Museum of Art) and Henry Moore’s Two Forms (b) (Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York). This figure is reproduced under the terms of fair use for academic purposes. The image is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Both works convey a similar theme by their analogous structural skeleton and inherent patterns of forces. In both cases, the themes of “protection” and “concern” are embodied in the way one figure (that is, the mother, the larger of the two units) bends over and reaches to a second figure (that is, the infant, the smaller of the two unites), thus “holding it down, protecting, encompassing, receiving it”. As Arnheim (1969: 269) points out, this curving wave shape, as seen embedded in both works, is an “abstract pattern” of form. This abstractness displays generality, which allows the work to reach the conceptual essence of a kind of thing.

Consequently, if images are indeed able to reach generality, as Arnheim claims and illustrates, and this generality is conditional for initiating conceptual metaphors, then, we might assume that images, and by extension films, are able to elicit conceptual metaphors as well. Thereby the crucial question to answer is as follows: how can this generality, of which Arnheim speaks in relation to paintings and drawings, and which is conditional for metaphor, be reached in cinema? Elsewhere (Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2016d: 121) we have argued that this condition of structure can be imposed onto the real-life in front of the camera by the forced actions of filmmaking (for example, mise-en-scene, framing, editing, and so on). Underlying this claim is a set of propositions which can be summarized as follows:

-

(1) Conceptual metaphors map the structure of concrete source domains onto abstract domains of experience.

-

(2) These source domains are driven by the inferential logic of image schemas (that is, abstract patterns of human sensory-motor experience).

-

(3) In film, these image schemas are vividly triggered by the application of various cinematic devices. As a result, the filmed event obtains a formal unity and generality that provides coherence: it acquires characteristics that, like language, can be analysed.

-

(4) The articulation of these structural patterns in the filmed event, in turn, allows the possibility of metaphorical expansion, that is, the inferential spatial logic of image schemas, as elicited through one or more cinematic devices, may be mapped onto the inferential logic of abstract target domains.

-

(5) In film, these target domains are mainly elicited metonymically, that is, they involve mappings within one single conceptual domain rather than mappings across two distinctive conceptual domains.6

Our previous work (Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2012, 2014b, 2015b, 2016a, b, c, d; Coëgnarts et al., 2016) can be seen as a series of attempts to explore and illustrate this line of reasoning with respect to various target domains of character subjectivity. Two such case-studies (character perception and character emotions) will be presented in the second application part below of this article.

From decoding signs to ES

If we assume that meaning is indeed embodied in the mode of expression, how, then, is the viewer able to infer this meaning? As mentioned in the previous part, according to the message or code model comprehension is reached effortlessly by way of decoding the syntax of the form of the message. On this view, the perceiver of the form comes to know the meaning of the form simply by looking at the objective language-based rules of the form in question. Such a rule applying approach to meaning, however, eliminates the significance of embodiment. For instance, it does not require that we take into account the embodied morphology of both communicator and recipient as well as the embodied underpinnings of the formal expression. One merely has to look at the linguistic meaning of the transmitted sign to formulate the concept to which the sign refers.

More recently, however, in conjuncture with the paradigm change from standard cognitive science to embodied cognition, Vittorio Gallese proposed an embodied approach to comprehension and social cognition, one that has its roots in the neurologic constitution of the recipient’s brain. He labels this approach “Embodied Simulation” (often shortened ES). The central idea underlying this concept is that “people reuse their own mental states or processes in functionally attributing them to others, where the extent and reliability of such reuse and functional attribution depend on the simulator’s bodily resources and their being shared with the target’s bodily resources” (Gallese and Sinigaglia, 2011: 518). This neural bond is driven by the discovery of mirror neurons in the macaque monkey brain and evidence for the existence of a similar mirror mechanism in the human brain (Gallese et al., 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1996; see also Gallese, 2001, 2003). Mirror neurons are claimed to map the sensory description of others’ expressive acts (for example, actions, emotions and sensations) onto the perceiver’s own motor, visceromotor and somatosensory representations of those acts (Gallese and Sinigaglia, 2011: 512). This mapping enables one to perceive the action, emotion or sensation of another as if she were performing that action or experiencing that emotion or sensation herself. Because they discharge both during the execution and the observation of a given behaviour, mirror neurons have been considered to be conditional for mind-reading and a variety of related concepts such as intersubjectivity, empathy and theory of mind. Hence, since film, like all other arts, exemplifies a mediated form of intersubjectivity between a filmmaker and his creative team (see also Gallese and Guerra, 2012), on the one hand, and the film viewer, on the other hand, it can be assumed that EST has a significant role in the way audiences grasp the meaning of actions and sensations in films. The line of reasoning underlying this hypothesis can be put as follows:

-

(1) Meaning in film is grounded in sensory-motor experiences (for example, through the mechanism of conceptual metaphor).

-

(2) Hence, to grasp this meaning, the viewer has to relate to these experiences (given the dependency of the former on the latter).

-

(3) Arising problem: Films deal with the perception of actions, sensations and emotions of others. How, then, can the viewer connect up with these expressive acts if he or she is not performing or experiencing these acts him or herself when viewing the film?

-

(4) Suggesting solution: Viewers are able to connect up with the expressive acts of others (and thereby with the meaning grounded in these acts), because simulation mechanisms in the human brain allow for such connections.

Examining this assumption has been central to the collaborative work between Gallese and film scholar Michele Guerra (Gallese and Guerra, 2012, 2015). In their specification of the relation between EST and cinema, they have pointed out that viewers are not only bodily engaged (in terms of sensory-motor motor cortex activation) during the observation of the actions and emotions of actors and actresses (the most obvious level of embodiment), but also during the observation of the actions of cinematic devices (for example, camera movements, changes of shot scale, different editing techniques, and so on). Support for this claim can be found in two experimental studies that were recently performed (Heimann et al., 2014, 2016). The results of these experiments demonstrated, among others, that the indicator of sensory-motor activity (the so called “central mu rhythm ERD”) may vary depending on the kind of editing system (for example, continuity editing versus violations of the 180 degrees rule) and the type of camera movement (for example, zoom, steadicam, dolly). For instance, with regard to the latter, the sensory-motor areas of the brain were found to be more active in cases for videos that were filmed while approaching the scene with a steadicam (Heimann et al., 2014).

If ES processes have a major role in prompting the actions of both characters and stylistic devices in the viewer, where, then, do emotions and top-down processes, these two other important components of the film experience, fit in this picture? Torben Grodal’s (2006, 2009) general model of visual aesthetics, which he labels the PECMA flow (short for perception, emotion, cognition and motor action), might provide some insight here. For instance, in the previous section we have already argued that significant forms (that is, forms that exhibit image schematic structures) are vital in embodying meaning in visual expressions. In light of this claim, Grodal has argued that the discovery of these essential features, which he situates within the first stage of the flow, works in tandem with positive emotional responses from the limbic system. As he argues, “the function of the visual cortex is finding salient forms in the chaos of information that arrives through the eyes and the brain receives a small emotional reward every time it discovers a significant form” (Grodal, 2006: 4).Footnote 4 Consequently, one might assume that ES processes in the viewer are more stimulated insofar they conjoin with the perception of significant forms that, from an emotional point-of-view, are more rewarding.8

Furthermore, Grodal (2009: 148–149) has claimed that emotions also have a significant role in the second stage of the PECMA flow, the process of associating or matching the significant input to stored memories and schemata. As he writes, these memories are stored with an “emotional tag or marker” that indicates how to relate to these significant forms. This stage can be seen as a top-down procedure insofar as this matching or reconstruction presupposes metacognitive functions (see also Shimamura, 2013: 133). Another top-down flow which is worth mentioning in light of this article is that what Grodal (2009: 152) refers to as “cueing attention”. Underlying this process is the neurological notion that only a fraction of the information will get focal attention. This priming and cueing of the viewer’s attention can be considered as a top-down process in that this selection process is influenced by forms of implicit knowledge that occur “unconsciously and with seemingly little effort” (Shimamura, 2013: 101). Thus, one can assume that embodied processes are not only directed towards sensory cues that are emotionally gratifying, but also towards sensory cues that already have been selected for attention.

For these reasons, it should be noted that the lack of reference to emotions and top-down processes in the above line of reasoning by no means implies the exclusion of them. Rather, the positioning of EST as a possible solution to the above problem presupposes the workings of both components.Footnote 5 Undoubtedly, it would be interesting, albeit outside the scope of this article, to further elaborate on these points.

It is through the ES system, then, that we will now illustrate that film viewers are able to attribute subjective states to fictional characters in film. They are able to do so, because these states are metaphorically and metonymically embodied in the cinematic form in such a way as to activate the viewers’ own sensory-motor experience world.

Embodying character subjectivity in cinema

When speaking of fictional minds or fictional subjectivity, we refer in this article to the inner life and the personality of fictional characters (see, for example, Eder, 2010; Reinerth and Thon, 2017). It involves such mental faculties as perception, cognition, evaluation, motivation and emotion. The property domain of the mind distinguishes itself, as Eder (2010: 24) argues, from other anthropological categories of characters such as corporeality (for example, external appearance, body language) and sociality (for example, social roles, power, status, and so on). The grounding problem of fictional subjectivity, then, amounts to the problem of how viewers are able to attribute mental states to characters given that these states are essentially abstract in nature. In what follows, we propose the embodied model of this article, as a solution to this problem. Consequently, this first requires that we narrow down the three central questions of our model as follows:

-

(1) How are subjective states embodied conceptually? Which metaphors and metonymies do we use to conceptualize the mind?

-

(2) How are the embodied solutions, as proposed at the conceptual level, embodied at the cinematic level?

-

(3) How are viewers able to “read” these embodied states in the cinematic form, on the basis of their own neurological embodiment?

Because the target domain of fictional subjectivity is still too broad, we will subject each question and corresponding level of analysis to two of its specific categories, namely visual perception and emotion. It goes without saying that a discussion of the first question alone would take an overview of an extensive body of research in the field of cognitive linguistics. For our purpose it is, therefore, enough to summarize some of its main findings. The second and third question will be assessed through the analysis of some concise film scenes.

Case-study 1: embodying character perception

Conceptual level

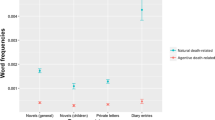

Evidence in cognitive linguistics often seem to broadly support five conclusions regarding the different ways people tend to talk about the mental faculty of perception (here defined as a relation between an object perceived O and a perceiving subject S) (see Fig. 4). First, humans tend to take the physical instrument of perception (for example, eyes, ears) as standing for the mental activity of perception as a whole (for example, seeing, hearing) (for example, “Keep an eye on him”; “Keep your eyes open”; “I cannot believe my ears”; “Walls have ears”) (Barcelona, 2002; Yu, 2003, 2004, 2008; Hilpert, 2006; Yamanashi, 2010). Second, humans tend to understand perception metaphorically in terms of spatial contact between S and O, whether or not accompanied by additional movement from O to S (reception) (for example, “A comet came into my sight”), or vice versa, from S to O (touching) (“My eyes picked out every detail of the pattern”) (Lakoff, 1995: 139; Yu, 2004: 676). Third, humans tend to speak of their perceptual fields in terms of containers (“The ship is coming into view”; “That’s in the centre of my field of vision”; “There’s nothing in sight”) (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980: 30). Fourth, humans tend to use their knowledge about the conceptual domain of perception, in turn, as a source domain for the conceptualization of higher mental functions such as knowing, thinking and understanding (for example, “I’m trying to see what you are saying”) (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999: 393–399; Yu, 2003, 2004; Gibbs, 2005: 97; Johnson, 2007: 165). Moreover, because this knowledge is in itself based on metaphor and metonymy, it has been pointed out that the same source domains of perception (for example, movement and physical contact) also have an essential role in how people conceive the higher faculties of the mind (for example, “How did you reach that conclusion?”). Fifth and last, scholars have also stressed the conceptual significance of perception for the way humans conceive the target domain of time (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, 1999; Boroditsky, 2000; Gentner, 2001; Gentner et al., 2002; Evans, 2003; Núñez and Sweetser, 2006). For instance, linguistic evidence shows that humans tend to map the location of the object perceived onto the time event (past or future) (“Christmas is approaching”; “We are approaching the end of the year”).

Formal level

Elsewhere (Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2014b, 20152015b, 2016a, b, c) we have argued that film is similarly capable of eliciting the conceptual solutions, as raised above, to express the characters’ subjective experience of seeing. It is through the forces of cinema (for example, framing, editing, camera movement) and the formal density they impose onto the first-order reality, that we have claimed, that the viewer is prompted to see a fictional character (S) and the object of his or her perception (O) as spatially connected to each other, and by further metaphorical extension that S sees O. This spatial connection between S and O takes the form of a mapping in which the inferential logic of one or more image schemas, as forced cinematically, are extended to structure the inferential logic of perception (that is, the relation between S and O). To illustrate this, let us consider two dynamic scenes of visual perception, respectively, taken from two films of Alfred Hitchcock: Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Notorious (1946) (see Fig. 5).10 In the first scene, the viewer shares the point of view of the murderer Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotton). The film shows the heroine (Teresa Wright) as she comes down the stairs, displaying to her uncle the emerald ring he has given to her, and which Charlie now wants to repossess as the initials of one of his victims engraved on it, exposes him as the Merry Widow killer. In the second scene, the viewer shares the point of view of the heroine Alicia (Ingrid Bergman). The camera reveals the keys of the mysterious wine cellar as they are lying on a desk in the middle of her Nazi husband’s room.

Embodying character perception in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (a–c) (USA 1943; DVD edition: Universal Pictures Video, 2003, PAL, 108 min) and Notorious (d–f) (USA 1946; DVD edition: Dutch Filmworks, 2003, PAL, 101 min). This figure is reproduced under the terms of fair use for academic purposes. The image is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In both cases the same propositional content (that is, the idea of “a character S seeing an external object O”) is instigated cinematically by connecting S and O spatially through a combination of two cinematic resources: editing (the point of view (POV) structure) and camera movement. As argued in Coëgnarts and Kravanja (2014b, 2015a), this kind of structure can be analysed as a cinematic manifestation of three conceptual mechanisms: (1) the metonymy EYES STAND FOR SEEING, (2) the metaphor VISUAL FIELDS ARE CONTAINERS and (3) the metaphor PERCEPTION IS TOUCHING. The first two mechanisms are embedded cinematically in the cinematic concept of the POV shot. The objective medium shots of Uncle Charlie and Alicia can be conceived as metonymical in that the vivid representation of their eyes and the bodily direction of their heads automatically trigger the idea in the viewer that they are looking at something outside the filmic frame. The following shots, showing what the characters are actually looking at, can be conceived as metaphorical extensions of the CONTAINER image schema. The space inside the container of the filmic frame is attracted to represent the visual fields of Uncle Charlie and Alicia. The outside, on the other hand, is mapped onto the areas they are not visually interested in. The second metaphor of vision is elicited cinematically by gradually moving from their full visual fields to the objects of their attention. Underlying this transition from long-shot to close-up is an extension of the SOURCE-PATH GOAL schema with the source and the goal as being, respectively, mapped onto the locations of S and O.

In later work (Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2016b) we extended these insights even further by arguing and demonstrating that these kinds of cinematic conventions for embodying character perception often lie at the base of the expression of the characters’ higher intentional acts such as remembering, desiring and knowing, in which the object perceived by the character can be mapped onto the object of his intentional act (for example, the memory, the object of desire, the idea). Likewise, one could argue that the two scenes above do not only exemplify the characters’ perception of seeing O, but also their desire of physically grabbing O, especially as the camera movement evokes a structure that mimics the characters’ potential approach to O (see also Gallese and Guerra, 2012: 200). However, in order for the viewer to anchor additional higher-order meaning to the perception of characters, often further contextual information is needed. This is especially the case with flashbacks that are introduced through the perception of characters (see, for example, Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2015b; Coëgnarts et al., 2016). To judge whether or not the perceived event by the character is temporally discontinuous (for example, to map O onto the past), one has to have perceived the content of the event before (equally through a prior filmed event or, differently, through textually channelled information). It is here that we touch upon a crucial difference between the mapping of image schemas onto perception, on the one hand, and the mapping of perception onto higher aspects of character subjectivity, on the other hand. In the first mapping, no additional knowledge is required. The audience can immediately verbalize their viewing experience as “We see a character S looking at something O”. We instantly arrive at this conclusion by virtue of the facial behaviour of S, and the contact between S and O, which is imposed upon the images cinematically by the application of various resources (for example, the POV shot, camera movement). In the second mapping, by contrast, this direct access is more complicated. We cannot directly verbalise our perception of the scene in terms of “We see a character S looking at the past O”. To connect the object of the character’s perceptual state with the higher mental state of a memory, we have to rely on knowledge that was already stored in working memory.

Receptive level

Having examined how cinema is equally capable of expressing the embodied solutions of the conceptual level in a purely non-verbal way, we are now able to examine the effects of these formal manifestations on the viewer’s sensory-motor system. If we assume that ES mechanisms are neurologically responsible for the way audiences interpret the scenes above in terms of character subjectivity, what, then, are the sensory-motor cues that cause the triggering of these mechanisms? Considering the sensory-motor descriptions of both scenes, one can identify two important levels of ES. First, there is the embodied level of acting: the characters’ facial expressions cause the audience to activate the same neurons as if they were performing the same expressions of the characters themselves. Consequently, because humans tend to see these particular facial expressions metonymically as standing for the mental activity of perception as a whole, it follows that audiences tend to “read” such scenes as instances of character perception. Second, there is the level of film style: in both scenes camera movement elicits a particular sensory-motor structure (the SOURCE-PATH-GOAL image schema) that recalls and simulates the experience world of the viewer. As Gallese and Guerra (2012: 202) observe, there are two distinct simulation processes at work here (see also Guerra, 2015: 148). First, there is the simulation process of approaching the objects of character perception (the ring and the keys). Second, there is the simulation process of grasping the objects triggered by the activation of the viewer’s canonical neurons. The simulation of approaching the objects brings them within the viewer’s simulated peri-personal space. As such the ring and the keys become potentially graspable objects. Consequently, because humans tend to map this sensory-motor knowledge metaphorically to structure the concepts of the mind (for example, perception, desires), it follows that the viewers are able to comprehend the scenes in terms of character subjectivity.

Case study 2: embodying character emotions

Conceptual level

As with perception, literature indicates various metaphorical and metonymical ways for conceptualizing emotions in language (see Fig. 6). For illustrative purposes we will limit ourselves to four common findings. First, evidence coming from both cognitive linguistics (for example, Kövecses, 2000: 134) and expert theories (for example, Ekman et al., 1980; Ekman and Friesen, 2003) supports the existence of a significant metonymical system according to which humans tend to attribute general emotional labels (for example, happiness, sadness, and so on) to specific physiological and expressive responses (for example, heart rate, change in the color of the face, facial expressions). Second, literature (for example, Radden, 1998; Kövecses, 2000) indicates that humans have a tendency to conceptualize their emotions in terms of containers (for example, “I’m in love”, “I’m in anger”) and the increase of emotional intensity as the increase of the amount/quantity of substance in the container (for example, “I’m full in love”) (Kövecses, 2000: 41). Third, people tend to extend the balance image schema to evaluate the “balance” of their emotional life (for example, Cervel and Peña, 2003: 207). Fourth and last, evidence supports the existence of an underlying conceptual metaphor that conceptualizes the negative loss of self (for example, when you are seized by anxiety or in the grip of fear) as loss of possession (for example, “He was possessed by the devil, he’s in the grip of his past”) (for example, Lakoff, 1996: 104).

Formal level

To illustrate how film is similarly capable of expressing the embodied solutions, as suggested above, in cinematic terms (see also Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2016c), let us consider another scene taken from Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (see Fig. 7). The scene captures the moment in the film when the heroine makes three unsuccessful attempts to call up her boyfriend for help against her Uncle Charlie. Each attempt is rendered in a single static image, each one different in style and appearance than the other images. In the first image, the framing of the shot is in balance. The camera is on the same level and height as the subject; the horizon inside the frame is parallel to the horizontal edges of the frame and perpendicular to the vertical edges of the frame. The camera is close to its subject. Charlie fills in the available space inside the container of the frame. Her facial expression and tone of voice reveal, in a metonymical way, a state of emotional anxiety. In the second image, however, after her second failed attempt to call him, we see a change in this balance. From a greater distance, the camera now looks down at Charlie. In this transition from medium shot to long shot, one can see the workings of the LOSS OF SELF IS LOSS OF POSSESSION metaphor. As hope of his coming fades away, she loses her control over the space inside the frame. Moreover, she is framed in such a way as to give the impression that she is captured between the two pillars belonging to the inside interior of the house (a frame-within-a frame configuration). She now is in the grip of fear. Her ability to move freely is even more diminished by the presence of the staircase in the third and last image. It visually recalls such linguistic expressions as “to be held behind bars”. The height and level of framing in this shot are even more distorted in comparison to the previous shot. The camera has distanced itself even further from the subject, thus giving the impression that she is being watched by someone else (Uncle Charlie?). Notice how carefully construed the scene is in terms of eliciting the intended emotional state of the heroine. Because the camera is distancing itself from the subject, one would expect that it would be harder for the viewer to infer the emotions of the character. After all, if the camera is further away, we are no longer able to read the emotions from her face. However, the contrary is true, by the forces of filmmaking the film is able to communicate and embody her intense negative emotional state in a purely visual and metaphorical way.

Embodying character emotions in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (a–c) (USA 1943; DVD edition: Universal Pictures Video, 2003, PAL, 108 min) and David Lean’s Brief Encounter (d–f) (UK 1945; DVD edition: ITV Studios Home Entertainment, 2008, PAL, 86 min). This figure is reproduced under the terms of fair use for academic purposes. The image is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

From this perspective it is worthwhile to compare the scene from Shadow of a Doubt with another cinematic evocation of the emotional life of a fictional character, this time taken from David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) (see Fig. 7). The scene describes the moment at the end of the film when Alec, a married doctor, bids her lover Laura, a married middle class woman, goodbye by touching her shoulder for a last time. After he has left the room, the camera centers on Laura’s illuminated face as she listens to the sound of his departing train. As the roaring sound of the train increases in volume, the camera tilts to the right, causing the horizontal image to slowly move counter-clockwise. As with Shadow of a Doubt, the BALANCE image schema is extended to structure the inner life of the heroine. Stylistically, this extension is made possible by the tilt function of the camera: by rotating the moving camera in a vertical plane, the horizontal image starts slowly to move counter-clockwise, thus suggesting a feeling of physical, and by metaphorical extension, emotional imbalance. However, in contrast to the scene from Shadow of a Doubt this emotional intensity is not additionally expressed by distancing the camera from the subject, but by gradually moving closer to the subject’s face. As we have argued in Coëgnarts and Kravanja (2016d: 127), the scene can be conceived as a merger of two conceptual metaphors, namely the INCREASE OF EMOTIONAL INTENSITY IS INCREASE OF THE AMOUNT OR QUANTITY OF SUBSTANCE IN THE CONTAINER metaphor and THE INCREASE OF EMOTIONAL INTENSITY IS MOTION metaphor. The starting point of the movement (that is, medium shot) can be mapped onto the non- or less intense emotional state of Laura (“there is still space in the container for the character to move freely in the frame”) and the ending point (that is, close-up) can be mapped onto the intense emotional state (“less space: Laura’s face is restrained in the frame”).

Receptive level

When evaluating the two scenes from above from the perspective of their effects on the brain’s sensory-motor system of the viewer, one can hypothesize at least three important types of activity. First, there is the visual impression of moving further away from the subject or moving closer to the subject. Shadow of a Doubt reaches the first effect by cutting straightaway from medium shot to long shot (thereby eliminating the various intermediate locations between starting point and ending point). Brief Encounter, by contrast, reaches the second effect by moving the camera from medium shot to close-up (thus showing the intermediate locations between starting point and ending point). Second, there is the elicited effect of changing the balance of the scene by altering the level and/or the angle of the shot. Third, there is the role of facial expressions, especially with regard to Brief Encounter. From the conclusions drawn from EST it can be assumed, then, that each of these descriptions have an important role in the activation of the of the sensory-motor regions of the viewer’s brain. Consequently, since these brain regions are believed to have an important role in the characterization of conceptual knowledge (see, for example, Gallese and Lakoff, 2005), it can be further assumed that the actions seen on-screen are equally of importance in the viewer’s inference of the emotional content of both scenes.

Conclusion

This article proposes a unified embodied model for understanding meaning in film based upon two influential theories of embodied cognition: CMT and EST. Both theories were attracted for the purpose of addressing two key questions, first, “How do films convey conceptual meaning to the viewer?” and second, “How is the viewer able to infer this meaning from the evidence provided by the film?”. In positioning the conceptual framework of CMT as a possible answer to the first question, we were faced with the ontological challenge of reconciling the conceptual nature of metaphor with the non-conceptual nature of cinema. A plausible resolution to this paradox was obtained by considering the significant role of film form. It was argued that cinematic devices such as camera movement and editing are able to structure the first order world in such a way as to enable a process of metaphorical mapping in which the inferential logic of image schemas is appropriated to express conceptual knowledge. This claim was further supported and illustrated by two cases of character subjectivity, namely, character perception and character emotion. Both categories of the (fictional) mind were shown to be grounded in structures of sensory-motor knowledge. How, then, are audiences able to resonate with these structures, given that they are not performing those activities themselves during the act of viewing the film? It is in addressing this second paradox that EST was brought into play. It was argued that viewers are able to connect up with these structures (and thereby with the meaning they embody), because simulation mechanisms in the viewer allow for such connections. For instance, the reason why viewers are able to attribute mental states to characters is because there is a distinctive matching or correspondence between their own experience world and the way the mental states of the characters are embodied in film through such resources as film style and acting. Viewers are able to infer the meanings (for example, about character subjectivity) from the cinematic form, because they embody the knowledge that filmmakers use to impose those meanings artistically. This article, however, is not without its limitations. First, given the ambition of combining two theoretical frameworks, the set-up of our article is unavoidably schematic and hypothetical in its treatment of the various relations between the three core concepts of our article (embodied metaphor, ES and cinema). Nevertheless, in adopting such a schematic approach, this article hopes to have provided the reader with some theoretical anchor points and promising avenues for further (more empirically driven) research on the implications of the interdisciplinary paradigm of embodied cognition for the study of film. Second, our article might wrongly give the impression that language only has a marginal role in the viewers’ assessment of the meaning of a particular filmic expression. It is true that the examples analysed in this article do not rely heavily on linguistic input. The viewer can almost immediately verbalize his or her film experience in terms of “I see a character in the act of perception” or “I see a character in emotional distress” without much further verbal aid. This, however, by no means implies that language is not essential. On the contrary, as we have stressed elsewhere (Coëgnarts and Kravanja, 2015b, 2016b), language more than often is crucial in guiding the viewer in his or her interpretation of the embodied non-verbal cues. Especially in cases where the viewer is supposed to “see” the scenes of character perception, in terms of higher mental functions (for example, knowing, remembering) the role of linguistic cues becomes particularly manifested. Moreover, it is the conviction of this article that one first has to consider the analytic and embodied structure of these modest examples before one can clearly look into the underlying structure of more complex cases of meaning-making in cinema, as encountered, for example, in European modernist cinema (Kovács, 2007) or puzzle films (Kiss and Willemsen, 2016). Especially, as the latter complex cases are more than often build upon the impediment of the former simpler cases (see also Coëgnarts et al., 2016). Third and last, one could make a similar point of criticism with regard to the paper’s lack of interest in the aural dimension of meaning-making in cinema, which, for lack of space, was excluded from this study.Footnote 6

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Coëgnarts M (2017) Cinema and the embodied mind: metaphor and simulation in understanding meaning in films. Palgrave Communications. 3:17067 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.67.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11

Notes

Gricean pragmatics refer to this thought as the “speaker’s meaning”. A speaker’s meaning can be defined as “an overtly expressed intention which is fulfilled by being recognized”. This might be quite different from its sentence meaning which is “a vehicle for conveying a speaker’s meaning” (Wilson and Sperber, 2012: 2). However, because we are dealing with images in this paper and not sentences, and because the notion of “speaker” tends to favour the verbal mode of communication, we prefer to use the more general and overarching term of “thought” instead. By doing so, we are placing the much complicated debate in analytic aesthetics concerning the role of authorial intentions in the interpretation of art (see, for example, Livingston, 2005,2010) outside the scope of this article.

“Again”, as the embodied, imagistic view of the mind is not an entirely new paradigm, but rather a continuation, as Barsalou (2008: 619) has pointed out, of a tradition of thinking that was considered dominant until the early twentieth century. Its historical roots go back as far as Ancient Greek Philosophy (Aristotle and Epicurus) and includes, among others, the intellectual heir of British empiricism (Locke, Berkeley, and Hume), American pragmatism (John Dewey) and French phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, Bergson).

It is precisely for this reason, to denote their conceptual nature, that metaphors and image-schematic structures are conventionally written in small capitals.

In animal discrimination learning, this principle of rewarding pattern recognition is also known as the “peak shift effect”. See also Ramachandran and Hirstein (1999) for its relation to human aesthetic preference.

This view preserves the chronology of Grodal’s PECMA model, which only makes reference to the notion of “mirror neurons” (that is, EST) in relation to the third stage of cognition and character identification, that is, after first having discussed the role of emotional activation and emotional labelling in relation to the first two stages, perception and association.

For studies that consider sound design and/or music from the perspective of embodiment theory (whether CMT or EST), we refer the reader to Chattah (2015),Fahlenbrach (2008) and Ward (2015).

We thereby follow a conception of “comprehension” that is similar to a specific mode of understanding, as distinguished by David Bordwell in his book Making Meaning (1989). In it, he pairs three categories of understanding movies with three corresponding categories of meaning: comprehension, which is concerned with “the overt facts about story or theme that are directly presented as such within the film” (that is, the “referential” and “explicit meanings”), explicative interpretation, which has “implicit meanings” as its object, and symptomatic interpretation, which aims to unravel “repressed (symptomatic) meaning” (Wilson, 2009: 163).

Because image schemas are conceived as primary structures that basically adhere to all human individuals, CMT might wrongly give the impression that metaphors are less subject to cultural change. Especially with the emergence of neuroscience, this claim to universalism has been prominent in literature. Later accounts, however, have criticized this one-sided emphasis on the bodily dimension of embodiment by stressing the importance of culture. For a good discussion of the relationship between conceptual metaphor and culture, see Ibarretxe-Antuñano (2013) and Yu (2008).

For a good discussion of the concept of “metonymy”, see also Lakoff and Turner (1989: 103).

On the role of viewers’ bodily affects and emotions in cinematic understanding, see also Plantinga and Smith (1999).

All film stills in this contribution are treated as visual citations, in accordance with the established guideline for fair use of film stills from DVDs in scholarly writings.

References

Arnheim R (1954) Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Arnheim R (1969) Visual Thinking. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Bálint K and Tan ES (2015) “It feels like there are hooks inside my chest”: The construction of narrative absorption experiences using image schemata. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind; 9 (2): 63–88.

Barcelona A (2002) Clarifying and applying the notions of metaphor and metonymy within cognitive linguistics: An update. In: Dirven R and Pörings R (eds). Metaphor and Metonymy in Comparison and Contrast. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin and New York, pp 207–278.

Barsalou LW (1999) Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences; 22 (4): 577–660.

Barsalou LW (2008) Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology; 59, 617–645.

Bernaerts L, De Geest D, Herman L and Bart V (eds) (2013) Stories and Minds: Cognitive Approaches to Literary Narrative. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE.

Bordwell D (1989) Making Meaning. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

Boroditsky L (2000) Metaphoric structuring: Understanding time through spatial metaphors. Cognition; 75 (1): 1–28.

Branigan E (2006) Projecting a Camera: Language-games in Film Theory. Routledge: New York, NY.

Buckland W (2000) The Cognitive Semiotics of Film. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Cervel M and Peña S (2003) Topology and Cognition: What Image-Schemas Reveal About the Metaphorical Language of Emotions. Lincom Europa: München.

Chattah J (2015) Film music as embodiment. In: Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (eds). Embodied Cognition and Cinema. Leuven University Press: Leuven, pp 81–114.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2012) Embodied visual meaning: Image schemas in film. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind; 6 (2): 84–101.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (eds). (2014a) Metaphor, bodily meaning, and cinema. Special issue of Image [&] Narrative; 15 (1): 1–4.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2014b) A study in cinematic subjectivity: Metaphors of perception in film. Metaphor and the Social World; 4 (2): 149–173.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (eds). (2015a) Embodied Cognition and Cinema. Leuven University Press: Leuven.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2015b) With the past in front of the character: Evidence for spatial-temporal metaphors in cinema. Metaphor and Symbol; 30 (3): 218–239.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2016a) The eyes for mind in cinema: A metaphorical study of the viewer’s experience. In: Fahlenbrach K (ed). Embodied Metaphors in Film, Television, and Video Games: Cognitive Approaches. Routledge: London/New York 129–144.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2016b) Perceiving causality in character perception: A metaphorical study of causation in film. Metaphor and Symbol; 31 (2): 91–107.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2016c) Perceiving emotional causality in film: A conceptual and formal analysis. New Review of Film and Television Studies; 14 (1): 440–466.

Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (2016d) From language to film style: Reassessing the role of conceptual metaphor in cognitive film studies. In: Grabbe LC, Rupert-Kruse P and Schmitz NM (eds). Yearbook of Moving Image Studies 2016 – Image Embodiment: New Perspectives of the Sensory Turn. Büchner-Verlag eG: Darmstadt, pp 108–134.

Coëgnarts M, Kiss M, Kravanja P and Willemsen S (2016) Seeing yourself in the past: The role of situational (dis)continuity and conceptual metaphor in the understanding of complex Cases of character perception. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind; 10 (1): 114–138.

D’Aloia A (2015) The character’s body and the viewer: Cinematic empathy and embodied simulation in the film experience. In: Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (eds). Embodied Cognition and Cinema. Leuven University Press: Leuven, pp 187–199.

D'Aloia A and Eugeni R (eds) (2014) Neurofilmology. Audiovisual studies and the challenge of neurosciences. Special issue of Cinéma & Cie; 14 (22/23): 9–26.

Eder J (2010) Understanding characters. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind; 4 (1): 16–40.

Ekman P and Friesen WV (2003) Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions From Facial Clues. Malor Books: Los Altos, CA.

Ekman P, Friesen WV and Ancoli S (1980) Facial signs of emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; 39 (6): 1125–1134.

Evans V (2003) The Structure of Time. John Benjamins: Amsterdam.

Fahlenbrach K (2008) Emotions in sound: Audiovisual metaphors in the sound design of narrative films. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind; 2 (2): 85–103.

Fahlenbrach K (ed) (2016) Embodied Metaphors in Film, Television, and Video Games: Cognitive Approaches. Routledge: London/New York.

Fodor J (1975) The Language of Thought. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

Fodor J (1983) The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. MIT Press: Cambridge.

Forceville C (2009) Non-verbal and multimodal metaphor in a cognitivist framework: Agendas for research. In: Forceville C and Urios-Aparisi E (eds). Multimodal Metaphor. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, pp 19–42.

Forceville C and Jeulink M (2011) The flesh and blood of embodied understanding: The source-path-goal schema in animation film. Pragmatics & Cognition; 19 (1): 37–59.

Forceville C and Renkens T (2013) The good is light and bad is darkness metaphors in feature films. Metaphor and the Social World; 3 (2): 160–179.

Gallese V (2001) The “shared manifold” hypothesis: From mirror neurons to empathy. Journal of Consciousness Studies; 8 (5–7): 33–50.

Gallese V (2003) The roots of empathy: the shared manifold hypothesis and the neural basis of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology; 36 (4): 171–180.

Gallese V (2009) Mirror neurons, embodied simulation and the neural basis of social identification. Psychoanalytic Dialogues; 19 (5): 519–536.

Gallese V (2011a) Embodied simulation theory: Imagination and narrative. Neuropsychoanalysis; 13 (2): 196–200.

Gallese V (2011b) Neuroscience and phenomenology. Phenomenology & Mind; 1, 33–48.

Gallese V and Guerra M (2012) Embodying movies: Embodied simulation and film studies. Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image; 3, 183–210.

Gallese V and Guerra M (2015) The feeling of motion: Camera movements and motor cognition. Cinéma & Cie; 14 (22/23): 103–114.

Gallese V and Lakoff G (2005) The brain’s concepts: The role of the sensory-motor system in conceptual knowledge. Cognitive Neuropsychology; 22 (3/4): 455–479.

Gallese V and Sinigaglia C (2011) What is so special with embodied simulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences; 15 (11): 512–519.

Gallese V, Fadiga L, Fogassi L and Rizzolatti G (1996) Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain; 119 (2): 593–609.

Gaut B (2010) A Philosophy of Cinematic Art. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Gentner D (2001) Spatial metaphors in temporal reasoning. In: Gattis M (ed). Spatial Schemas and Abstract Thought. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, pp 203–222.

Gentner D, Imai M and Boroditsky L (2002) As time goes by: Evidence for two systems in processing space => time metaphors. Language and Cognitive Processes; 17 (5): 537–565.

Gibbs RWJ and Perlman M (2006) The contested impact of cognitive linguistic research on psycholinguistic theories of metaphor understanding. In: Kristiansen G, Achard M, Dirven R and de Mendoza Ibáñez FJR (eds). Cognitive Linguistics: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, pp 211–228.

Gibbs RWJ (2005) Embodiment and Cognitive Science. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Gibbs RWJ (2006) Metaphor interpretation as embodied simulation. Mind & Language; 21 (3): 434–458.

Glenberg A and Robertson D (2000) Symbol grounding and meaning: A comparison of high-dimensional and embodied theories of meaning. Journal of Memory and Language; 43 (3): 379–401.

Grice HP (1989) Studies in the Way of Words. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

Grodal T (2006) The PECMA flow: A general model of visual aesthetics. Film Studies; 8 (1): 1–11.

Grodal T (2009) Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film. Oxford University Press: New York, NY.

Grodal T (2016) Film, metaphor, and qualia salience. In: Fahlenbrach K (ed). Embodied Metaphors in Film, Television, and Video Games: Cognitive Approaches. Routledge: London/New York, pp 101–114.

Guerra M (2015) Modes of action at the movies, or re-thinking film style from the embodied perspective. In: Coëgnarts M and Kravanja P (eds). Embodied Cognition and Cinema. Leuven University Press: Leuven, pp 139–154.

Hampe B (2005) Image schemas in cognitive linguistics: Introduction. In: Hampe B (ed). From Perception to Meaning: Image Schemas in Cognitive Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin & New York, pp 1–12.

Hasson U, Landesman O, Knappmeyer B, Vallines I, Rubin N and Heeger DJ (2008) Neurocinematics: The neuroscience of film. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind; 2 (1): 1–26.

Heimann KS, Uithol S, Calbi M, Umilt MA, Guerra M and Gallese V (2016) “Cuts in action”: A high‐density EEG study investigating the neural correlates of different editing techniques in film. Cognitive Science. (advance online publication 24 November) doi:10.1111/cogs.12439.

Heimann KS, Umiltà MA, Guerra M and Gallese V (2014) Moving Mirrors: A high density EEG study investigating the effects of camera movements on motor cortex activation during action observation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience; 26 (9): 2087–2101.

Hilpert M (2006) Keeping an eye on the data: Metonymies and their patterns. In: Stefanowitsch A and Gries ST (eds). Corpus-Based Approaches to Metaphor and Metonymy. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin and New York, pp 123–152.