Abstract

The academic literature on financial reporting and accounting is limited in the football industry compared with other sectors of the economy. The purpose of this paper is to critically analyze the financial communications of football clubs with reference to the impairment test for football players. According to the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), an impairment test measures whether a balance sheet item is actually worth the amount stated on the balance sheet. The balance sheet amount should be reduced if the impairment test indicates a lower value. At the end of each reporting period, a football club is required to assess whether there is any indication that a footballer may be impaired. The paper aims to show that the financial communications and reporting disclosed by football clubs about the impairment test procedure is poor and inadequate. It is argued that the UEFA regulations have gaps that ought to be filled and that IFRS are not perfectly suitable for companies operating in specific business sectors such as the football industry. The study is based on an extensive literature review and an analysis of previous academic studies. In addition, this study investigates the best practices reported in the footnotes of the financial statements of several football clubs in Italy, England and Scotland. These clubs operate and play in different jurisdictions and so also adopt different accounting standards. The research study reveals that only a few of the clubs studied give information about the impairment test in the footnotes to financial statements. This confirms that the financial communications of football clubs are limited. Secondly, only one club studied (Rangers F.C.) acknowledges that a possible external indication for performing an impairment test might be the failure to achieve the sporting goals fixed at the beginning of the sporting season. Our findings suggest that UEFA, FIFA and local football associations should promote new regulations aimed to improve the accuracy of the financial disclosure of football clubs. They should also introduce as an important external indicator to perform the impairment. This kind of failure has a negative impact on football clubs’ revenues. These findings may also have interesting implications for other sporting organisations. This article is published as part of a collection on corporate governance, the sports industry and intellectual capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the last 20 years the European football industry has come a long way. Football has become a worldwide phenomenon, its revenues have quadrupled and matches have become major sporting and commercial events. Despite the growth of this industry, the academic literature has not critically examined in depth the financial communications of football clubs. Morrow (2006) underlines that “while a substantial body of contemporary academic literature now exists on the economics of football [...] the literature on financial reporting and accounting is more limited”.

One major problem about the financial communications of football clubs is strictly linked to the accounting and disclosure of the footballers in the financial statements. The registration of the players represents, along with the stadium and the training infrastructure, the main asset of many professional football teams.

Section “Multiannual rights to exploit the performance of footballers” of this report shows that the football players can be of three main types: players carried owing to a transfer (from another club), free agent players and players promoted from the youth squad to the first team. Only in the case of players registered in consequence of a transfer is it possible to disclose a credible assessment of the market value of the player because there has been a payment to another club. After being properly valued, the football players subsequently should be capitalized and amortized for accounting purposes. Then, the football clubs must verify the existence of potential impairment losses as determined by UEFA (2015).

UEFA is inspired by International Accounting Standard 36 (Impairment of Assets). The UEFA regulations (2015) give wide discretion as to the identification of the cash-generating unit (CGU) and the indications for impairment. However, Section “Youth Players Registrations' Accounting Policy: are IAS/IFRS inadequate for the football industry?” of this article, which focuses on the accounting policy for youth player registrations, indicates that IAS/IFRS (IAS 38 specifically in this context) are inadequate for the football industry.

Section “Impairment Test” of this article critically analyses the application of the impairment test for multiannual rights to exploit the performance of footballers (hereinafter MREPFs), with the specific objective of analysing the relationship between the sports and financial performance of football clubs. Only one club (Rangers F.C.) covered in this study acknowledge that a possible external indication to proceed to the impairment test might lead to a failure to achieve the sports goals fixed by the team’s management at the beginning of the sporting season. This kind of failure has a negative impact on the revenues of football clubs.

The study shows that the financial communications and reporting disclosed in the footnotes to the financial statement by football clubs is poor and inadequate for investors, especially regarding the impairment test procedure, and that UEFA’s accounting regulations (2015) have gaps to be filled.

Multiannual rights to exploit the performance of footballers

The MREPFs represent the main accounting issue of football clubs (Pavlović et al., 2014). They are defined as “the tie between the athlete and the club, which may be construed as an atypical intangible asset, a sort of asset that gives the rights to exploit the performance for a set amount of time and that is sold by one club to another in case the footballer is transferred” (Fiori, 2003).

This is a very relevant issue for the financial communications disclosed by football clubs. It is now a widespread assumption (Gelmini, 2014) that the MREPFs present all the requirements to classify them as “assets”. Consequently, they should be specifically mentioned in the balance sheet and they must be subject to specific and compulsory test that verify the occurrence of impairment losses.Footnote 1 They can be separately purchased and sold from the football club in a market whose trade leads to a reliable measurement of their value.

Therefore, some scholars (Mancin, 2009; Amir and Livne, 2005; Vernhet and Augè, 2010) agree in considering these rights as “intangible” assets because the football club that exploits them, even just for the period assigned by contract, does it exclusively for the purpose of obtaining future economic benefits. The benefits derived from the acquisition of each right are represented by the on-pitch performances of the player, which are the key factor to realize revenues from gate receipts, sponsorships, media rights and merchandising.

IASB issued IAS 38 that “outlines the accounting requirements for intangible assets, which are non-monetary assets which are without physical substance and identifiable. Intangible assets meeting the relevant recognition criteria are initially measured at cost, subsequently measured at cost or using the revaluation model, and amortized on a systematic basis over their useful lives”. The hallmarks of intangible assets promoted by IAS 38 are: identifiability, control, existence of future economic benefits.

The identifiability is fulfilled when the intangible asset is divisible and it arises from agreements or other legal rights2; as mentioned before, the MREPFs respect this element.

The control is within the football industry the most critical issue. Legal intervention and changes to the transfer system agreed between UEFA, FIFA and European Commission led to a greater freedom of movement for the footballers (Morrow, 2003). Generally speaking, a player can sign an employment contract for a period ranging from one to five years.Footnote 2 However, according to FIFA regulation (2016), the protected period for contracts between clubs and players has a duration of two years. At the end of this time span, there is the possibility for the footballer to get a disengagement from the contract and to request the termination of his contract unilaterally for just cause.4 Therefore, in the worst-case scenario, although the football company acquires the right to exploit the performance for 5 years, the future economic benefits would cover only part of the recovery time provided for in the initial contract.

Acquisition of MREPFs: the carrying value

The cost for the purchase of the MREPFs can be specified as follows:

1. Acquisition of rights of a player under legal agreement with another club. The indemnity due to the transferor team is paid in money.

The carrying value of MREPFs corresponds to the amount of money paid. In other terms, it represents its acquisition cost (Morrow, 1999). In theory, IAS 38 specifies that this value must include all the ancillary costs.Footnote 3

The most common ancillary costs are the agent’s fees, the percentage from the transaction paid to the initial club financial intermediary’s fee and other professional figures as well as registration fees.

UEFA provides fulldiscretion to European football clubs regardingthe accounting standards (both national and international) to be adopted. However, several clubs use the International Accounting Standards so that the compliance to IAS 38 has become a widespread requirement for most of them (Oprean and Oprisor, 2014). The cost of footballer’s registrations at their historical cost is the most suitable policy for clubs to adopt (Morrow, 1997).

2. Purchase of rights to exploit the performance of a free agent footballer.

The recognition of acquisition costs related to the free agent6 turns out to be less easy to identify because the buyer club does not carry explicit charge for the purchase of the right. At the end of the footballer’s contract, no fee is required to transfer the registration (Morrow, 2006).

Gelmini (2014) compares this kind of acquisition with a “purchase free charge” to be valued in the financial statement at fair value. Such approach would provide an initial check of the fair value of the benefits acquired through a “stand-alone” assessment of the economic value of the player. But the same scholar recognizes that this process turns out to be quite articulate and uncertain. Comparative values with players under contract are inaccurate because their negotiation ability is greater and the fair value determined of market parameters cannot be carried out (Oprean and Oprisor, 2014).

Hence, the free agent footballers are not registered as assets since there is no credible ground for a valuation so it is recommended to issue a free agent player among income statement rather than a cost capitalized in the balance sheet.

3. Temporary acquisition of a footballer.

FIFA stated that “any professional player may be loaned to another club based on a written agreement between him and the clubs concerned. Any such loan is subject to the same rules as applied to the transfer of players” (FIFA, 2016). The minimum loan period shall be the time between two registration periods.Footnote 4

In the present case, the surrendering company—keeping the right—continues to amortize it in relation to the duration of the contract and to carry the MREPFs among the intangible assets. Simultaneously the club realizes a gain related to the temporary assignment which is represented by the fees paid to the assignor by the assignee.

4. Acquisition of rights of a player under legal agreement with another club. The amount paid to the transferor football club is paid partly in money and partly with the transfer of another player.

In this case, the carrying value of MREPFs is equal to the sum of the money paid and of the value attributed to the footballer offered for the trade. According to IAS\IFRS, this exchange must be done carrying the players at their book value (Gelmini, 2014).8

Depreciation of MREPFs

The amortization process must begin when the player is acquired (UEFA, 2015). The MREPFs are amortized over the length of the respective contract to an estimated residual value (Rowbottom, 2002), according to the recommendations of IAS 38.Footnote 5 It is widespread the idea (FIGC, 2009) that a single depreciation method must be adopted and the depreciation must be done individually for every single player. The depreciation method of the rights of players can occur in equal (more applied and known as straight-line method) or in decreasing depreciation charges.10 IAS/IFRS consider the straight-line method as the only acceptable method when it is not possible to determine reliably the benefits obtained using an intangible asset.Footnote 6

Finally, the original amortization plan undergoes changes resulting from the extension of the contract in case of a renewed agreement. In this case, the new amortization plan must consider the net book value of the right to the date of the contract extension and the new duration.

The process of amortization ends when the right is transferred among the assets “available for sale”, pursuant to IFRS 5.

Earning/charges due to transfer of players

The MREPFs are separable so they can be sold on the market to another club because they are considered intangible assets. UEFA sets that “the profit (or loss) on the disposal of a player’s registration to another club to be recognized in the profit and loss account. It corresponds with the difference between the disposal proceeds and the residual carrying value of the player’s registration in the balance sheet as at the date of the transfer” (UEFA, 2015).

Youth players registrations' accounting policy: are IAS/IFRS inadequate for the football industry?

In the professional clubs, the benefits associated with a successful investment in youth academies have helped to focus attention on talent identification and development models (Reilly and Gilbourne, 2003). The increased value of young players will lead the way to higher investments in youth academies, scouting and development by European football clubs (Relvas et al., 2010).

The costs incurred for the promotion and organization of the youth academy can be generally compared with research and development costs because they have long-term rewards. The possible recovery of these costs by the future use of these players suggests to capitalize them.

However, IAS/IFRS state that these costs must be recognized directly in the income statement. One reason may lie in the fact that IAS/IFRS emphasize on the reliability of financial statement values and their subsequent recovery. The impossibility of capitalization of internally generated players’ costs is stated by IAS 38 which forbids the capitalization for costs of intangible assets constituted by the same company (Kulikova and Goshunova, 2014).

Furthermore, Oprean and Oprisor (2014) underlined that underage players cannot sign professional contracts. Thus, the clubs have not right to exploit them: as consequence, there is no control over these players. Afterwards, in case they should sign a professional contract, their status quo will have a significant change as they can be accounted as free agents.

UEFA (2012) agrees with this view, stating that “since the home-grown players are not acquired with a fee, they cannot be capitalized on the balance sheet because they do not meet all the criteria for an intangible asset. Only direct costs of acquiring a player can be capitalized and they should be depreciated over its useful life. If these rules are not followed, clubs will be fined and possibly excluded from European competitions such as Champions League and Europa League”.

Nevertheless, some scholars argue that the carrying value of the youth team’s players should be put in evidence among the clubs’ assets. Lozano and Gallego (2011) demonstrated that ignoring costs of youth players can lead to a huge gap between the book value of the club and its market value. They show that some footballers playing in Barcelona F.C. as Messi, Iniesta, Busquets, Piqué are not disclosed in the balance sheet because they have no accounting value. They are home-grown players, so no transfer fees have been paid when they became part of the first team. Marotta (2014) emphasizes that Barcelona F.C.’s roster has a market value of €620 million, meanwhile its carrying value is €175 million, causing €445 million of potential hidden reserves because the most important (and with more market value) players come from the youth team.

Accordingly, all the investments made for the development of young players should be carried among the intangible assets of a football team. These players—through their performances carried out in the first team—may be able to produce economic advantages to the club. IAS model prohibits the capitalization of the costs related to youth team and it does not guarantee an appropriate degree of disclosure about their values.

Therefore, the nature of football clubs and the behaviour of many of their stakeholders leave these financial reports inadequate to perceive objectives and needs of stakeholders (Morrow, 2013).

Impairment test

UEFA Club Licensing system forces clubs that adopt the capitalization policy to write off the capitalized costs over the length of the player’s contract.12 Furthermore, as seen above, the MREPFs are recognized in the balance sheet among the intangible assets, so the football clubs must verify the existence of potential impairment losses as determined by UEFA (2015) and by IAS 36.Footnote 7 Consequently, the clubs must carry out an annual impairment test (Morrow, 2006).

IAS 36 requires that assets be carried at no more than their recoverable amount. To achieve this objective, IAS 36 requires entities to test all assets that are within its scope for potential impairment when indicators of impairment exist. UEFA (2015) agrees about the compulsoriness of impairment test for MREPFs, stating that “if the recoverable amount14 for an individual player is lower than the carrying amount on the balance sheet, the carrying amount must be adjusted to the recoverable amount and the adjustment charged to the profit and loss account as an impairment cost. It is recommended that each licensor requires each of its licence applicants to apply consistent accounting policies in respect of player registration costs”. It is evident that UEFA is based on IAS 36.

Methodology

This study is based on a review of the pertinent academic literature, international accounting regulations and the FIFA and UEFA regulations. In addition, it assesses the best practices of several football clubs based on an analysis of their financial statements. These financial statements provide information annually on the overall financial position of the club at a given date. For football clubs this date is usually at or around the end of the sports season (Morrow, 1999). We examine several footnotes to the financial statements of football clubs that are from different countries (England, Italy and Scotland), playing in different categories in 2016 (First and Second League) and that adopt different accounting standards (International Financial Reporting Standards and Local GAAP). This study only assesses the financial statements of clubs that are published on their official websites. The football clubs that we have considered in the sample are the following: Juventus F.C., A.S. Roma, S.S. Lazio, Manchester United F.C., Manchester City F.C., Chelsea F.C., Arsenal F.C., Tottenham Hotspur F.C., Southampton F.C., Liverpool F.C., Leicester City F.C., West Ham United F.C, Birmingham City F.C., Norwich City F.C., Rangers F.C. and Celtic F.C.

Identifying cash-generating unit in the football industry

The first issue for football clubs’ directors is to identify the cash-generating unit (CGU)Footnote 8 to properly assess the value in use of the MREPFs.

Mancin (2009) considers appropriate that football companies use the estimated value in use not for every single player but considering the whole team. This is consistent with the inability of the individual player to produce single-handedly cash flows and with the provisions of IAS 36.16 From this point of view, the smallest identifiable group of assets that generates independently cash inflows is constituted by the team as whole. Moreover, the same scholar does not consider appropriate to resort to fair value in determining the recoverable value.

On the contrary, Biancone and Solazzi (2012) believe that the smallest CGU could be made up of individual players. In support of the possibility to consider an individual player as a CGU, in recent years there have been several episodes that have shown that the most famous players can single-handedly increase the revenues of the football club. The most striking example certainly is the sale of the shirts with their name and number.Footnote 9 This example allows to assume that a single football player may be capable to generate cash flows—or at least part of them—of the club independently. For this reason, it could be argued that the single player would be subject to impairment test as self-standing intangible asset.

UEFA (2015) partially agrees with this view because it recommends to proceed to an impairment test individually for every player’s registration.18

In addition, it is possible to determinate the fair value for every single footballer. According to IAS 36 paragraph 70Footnote 10 there is reference market, that in the football sector is so-called “transfer-market”, in which it is possible to estimate the fair value based on the available information and on the possible bids received by the owner-team of the player. So, it is possible determinate the recoverable amount for an individual player.

We observe that the football clubs identify their CGU in relation to the composition of their assets and to the accounting recommendations promoted by the various national football Federations.

In Italy, Juventus F.C.20 and A.S. RomaFootnote 11 —that adopt the IFRS—circumscribe the CGU to the individual player as recommended by Local Accounting Recommendation no. 1 (FIGC, 2009) that invites to carry a loss in the income statement when a player gets injured or resolves his contract.22

In England, the situation is completely different. Especially the clubs that play in Premier League are not only owners of the MREPFs but also of the stadium where they play and of the facilities for training where the players train.

Thus, the directors of English football teams prefer to consider these assets all together as the smallest identifiable CGU. The management of Manchester United (Red Football limited, 2016) does not consider any individual player as single cash-generating unit, being the operations of the Group as a whole CGU.Footnote 12 According to the accounting policies of Manchester United, the management of Arsenal—that sets up the financial statements in accordance with domestic GAAP (FRS 102)—identifies the smallest CGU to include all the playing squad and the football operations of the Group as a whole.24 To be accurate, both in Manchester United and Arsenal financial statements, the smallest CGU is identified with a rather generic name: “operation of the football club”. Thus, it has shown that both teams do not refer to a single player in the identification of the CGU.

Staying in England and in Premier League, some football teams disclose more information about their impairment test. The managers of the Tottenham HotspursFootnote 13 “consider the smallest CGU as the set of all the first team players, the stadium and the training facilities because the football team is the owner of all of them”.

Dropping down by category in Football League Championship, the same level of disclosure given by Tottenham Hotspurs is also provided by the Birmingham F.C. The club does not deem appropriate to determine the value in use of an individual footballer in isolation as that player. Furthermore, the club also believes that all the footballers cannot generate cash flows even when considered together. Accordingly, Birmingham F.C. considers the smallest CGU to contain all first team players, the stadium and the training facilities.26

Therefore, the managers of football clubs that own not only the MREPFs but also other assets such as the stadium or training facilities, prefer to perform the impairment test for a CGU that includes not only the individual player or the whole set of players, but also all those assets that are used to perform the set of typical football club operations.

However, there are exceptions to the rule. Staying in Football League Championship, Norwich F.C. owns the stadium and the training facilities where its footballers play. Nevertheless, its management does not believe it possible to assess the value in use of an individual footballer in isolation but does not give more information about the texture of the cash-generating unit; it would seem that the smallest CGU is identified as first team players as whole without considering the stadium or other tangible assets.Footnote 14

Indications of impairment

To carry out the impairment test for MREPFs, the football clubs should firstly consider the information provided both from internal and external sources (or indications), according to IAS 36.28

Because of the specific nature of activities of a football team, UEFA (2015) indicates in its Accounting Recommendations some case studies whereby a company must resort an impairment loss that fall within the category of internal sources.

For example, when a player decides to leave the agonistic activity due to a personal intention or injury, the football team that exploits his performance must carry to the income statement—as depreciation\impairment loss of the related intangible asset—all part of non-amortized cost because it will not gain future economic returns by the player anymore.

A similar write-down of the net book value must be carried out because of a serious injury suffered by the player who forces him to abandon the competitive activity.Footnote 15

These two indications of impairment are applied not only by football teams which consider an individual player as CGU but also by those that consider within the same CGU even the stadium and other tangible assets. According to these accounting recommendations, when the players improbably contribute to the future economic returns of the CGU, the carrying value of the footballer is eliminated from the cash generating unit. Afterwards, this is assessed for impairment in isolation to estimate the player’s fair value less any costs to sell.30

In addition to the above recommendations, Biancone and Solazzi (2012) added as internal impairment sources also the consensual termination of contract between the parties. It falls within the internal sources because only the management of the football club and its player are aware of their destinies and intentions. For example, Juventus F.C. in 2015 has carried out an impairment test for the right to exploit the performance of the player Fernando Llorente because of consensual division of the player's contract. The operation of termination of the contract that occurred on August 2015 has forced the managers of Juventus resulted to carry out a complete write-down of the residual value of the right (€1,519 million) in the year 2014/2015.

Finally, according to IAS 36.12 we can add as internal the planned sale of a player who is consequently included among the “assets to be sold”. For example, Birmingham F.C. specifies this possibility in its footnotes to the financial statement.Footnote 16

It is easy to point up that the accounting recommendations promoted by UEFA keep in mind only of the internal sources, neglecting the external indications reported by IAS 36. This represents a serious issue.

Since there are not official recommendations by UEFA, the indications of impairment from external sources appear to be difficult to classify. Biancone and Solazzi (2012) believe that an external source that activates the impairment test may be linked to sports performance so below than expected by club that the market value of the footballer is decreased. Consequently, if the expected cash flows are lower than footballer’s book value, the club should carry an impairment loss. The main problems associated with this type of external source are inherent to two aspects. Firstly, the smallest CGU can be represented only by the individual player. However, we have shown as it is quite common in the accounting practices of the football clubs, especially English ones, to do not consider the individual player or the team as whole as the smallest CGU but also to add the stadium and training facilities owned by the club. Secondly, a further criticality would be to determine the expected level of performance of an individual player different from those realized. For each player and for each “on-pitch” role a specific performance is required. It would be complicated and expensive for the football clubs to determine all these elements.

At this point, expanding the boundaries of CGU going to incorporate all the players who are part of the first team, we believe that it is possible to adapt the model proposed by (Biancone and Solazzi, 2012) about the sports performance of an individual player to the sports performance of the first team as whole. The academic literature shows that sports performance influence the financial performance (Pinnuck and Potter, 2006) and even the stock performance of the football companies (Duque and Abrantes Ferreira, 2005). Therefore, if a team has sports performance deemed positive by the management, the club will generate more cash flow that could lead to a higher value in use. However—at the same time—there is the possibility that the value in use of the CGU could decrease due to poor sport performance forcing the managers to carry an impairment loss.

For this reason, a possible external source to proceed to the impairment test might be the failure to achieve the sports goals fixed by the team’s management at the beginning of the sports season.

For example, this procedure is adopted only by the Scottish football team Rangers F.C. In its annual report, it discloses both the mode of procedure and indications of the impairment. Firstly, in the section “Impairment testing procedures” Rangers’ management states its key assumptions.32 Subsequently, as part of the impairment testing, Rangers’ managers carry out a sensitivity analysis to observe the Critical values—resulting in impairment charge related to football performance, player costs and discount rate. The weighted average results from the sensitivity analysis were taken to determine the estimated net present value of the CGU.

Among the key assumptions there is the item “Football team performance” in which the management expects that team qualifies for the Europa League in short term.Footnote 17 Thus, the failure to achieve the “Football team performance” objective/key assumption activates the impairment test. It is assumed that not having achieved its sports performance goals, the cash flow will be influenced in such a way that the value in use of the CGU will decrease.

Therefore, it should not be underestimated the idea that the impairment test could be deemed to constitute the missing link between sports and financial performance of football clubs.

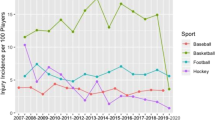

Nowadays, there are several studies that demonstrate how sports results of a football club impact on the financial performance and on the football club's ability to generate future cash flows. For example, in Italy it has been shown that football performances have a strong impact on the economic results of the club (FIGC, 2016). In the event of relegation to Serie B from Serie A, the average34 value of the production falls by €15.8 million and net income goes down by €4.8 million. At the same time, the average value of EBITDA decreases by €6.1 million meanwhile the average of total cost of production goes down by €7.3 million (Fig. 1).

Similarly, also the qualification for Europa League for a club that the previous year played Champions League has a negative impact on its financial performance. For example, the averageFootnote 18 value of the production falls by €45.5 million and the average of total cost of production decreases by €7.1 million. At the same time, the net income decreases by €31.3 million and the average value of EBITDA goes down by €34.5 million meanwhile (Fig. 2).

From this report, there ensues that sports performance of Italian football clubs have a strong impact on their financial performance, especially on those that miss the qualification to Champions League. The Champions League certainly is the competition that guarantees the highest return of cash flows, more than any other European as well as National competition, since the total funds to be distributed to clubs participating in the UEFA Champions League amounted to €1,257 billion (UEFA, 2016).

Reversing the impairment loss

IAS 36 applies a general rule which is explicated in its paragraph 110, which says that “An entity shall assess at each end of the reporting period whether there is any indication that an impairment loss recognized in prior periods for an asset other than goodwill may no longer exist or may have decreased. If any such indication exists, the entity shall estimate the recoverable amount of that asset.” Therefore, the aim of IAS 36 is to promote the reinstatement of value if there is no longer the causes or indications that led to the impairment loss. The amount of the reinstatement of value is equal to the difference between the new carrying amount and the previous one.

UEFA makes no reference to the restoration of impairment losses within its accounting recommendations36 . Thus, UEFA has to provide this legal vacuum because also IAS 36 specifies that a company can reverse impairment losses.

Therefore, considering the sports performance such external sources to perform an impairment test, if a football company has failed to achieve the seasonal sports goal—devaluing its CGU—the same company, if the following year achieves the sports performance goal, should carry out an impairment reversal because its CGU is again able to produce the same previous cash flows arising from the new sports performance. The classic example is the promotion to the national top league after a previous relegation.

This is something to be reckoned with and which emphasizes that sports performance can highly be the missing link between football clubs and impairment test. The report previously illustrated also deepens the financial performances in case of Italian football teams that attain the promotion from Serie B to Serie A (Fig. 3).

In case of promotion to Serie A, (FIGC, 2016) noted that in the last 5 years the value of the average production of the football team promoted has increased by €23.3 million as well as the net income by €4.9 million. At the same time, the average value of EBITDA enhances by €6.1 million meanwhile the average of total cost of production goes up by €10.4 million.

Even more positive results occur when an Italian football team qualifies in Champion's league after the previous year had qualified for the Europa league (Fig. 4).

The production value of a company that qualifies for the Champions League grows by an average by €32.8 millionFootnote 19 and the net income is improved to €4.5 million. Moreover, the qualification in the Champions League also ensures that a football company can increase its cost of production by €22.1 million.

Therefore, the report on Italian football proposed by FIGC shows that sports performances have a strong impact on the economic and financial performance of Italian clubs.

Conclusion

Firstly, this study shows that the financial communications disclosed by football clubs are inadequate. In addition, football companies adopting an IAS model do not guarantee an appropriate degree of disclosure that IAS specify. Therefore, this study would support the conclusions of other studies that specify that the IAS are not perfectly suitable for companies operating in specific business sectors, such as the football industry.

Secondly, a critical topic for the management of football clubs is the impairment test for footballers. The first issue is to determine whether, or to what extent, the CGU is made of individual players or the whole football team. Therefore, to properly evaluate the MREPFs, the football team should resort to an impairment test for the individual footballer as well as the team as a whole. It is important to note the possibility that a player may not depreciate himself as an individual but as a member team (for example, following poor sports results).

Perhaps the most interesting issue derives from the difficulty of generating enough inflows in the future to cover cash outflows resulting from poor sporting performance (for example, failure to qualify for the UEFA Champions League or relegation to a lower league and so on). In such cases, it is possible that the value in use of the CGU could decrease in such a way that the club must write down the MREPFs.

For example, Rangers F.C. specifies both the procedure and indications of the impairment test. Among the key assumptions there is the item “Football team performance” in which the management expects that the team qualifies for the Europa League in the short-term. Consequently, any failure to achieve the “Football team performance” objective/key assumption activates the impairment test. It is assumed that in the event its football performance goal is not achieved, the cash flow will be affected in such a way that the value in use of the cash-generating unit will decrease.

The results of this article could be a useful starting point for future research aimed at considering the significance of the impairment test in the financial reports of football teams. The main limitation of this study is the sample size: we only observed some clubs that participate in the Italian, English and Scottish championships. Future research should broaden the sample size and add the best practices of clubs that take part in the championships of other European countries such as Spain, Germany and France. Furthermore, comparison with other sports associations’ regulations might be useful to fill the gap that UEFA regulations have shown on this financial reporting topic.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated during the current study. Any datasets analysed are indicated in the paper.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Maglio R and Rey A (2017) The impairment test for football players: the missing link between sports and financial performance?. Palgrave Communications. 3:17055 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.55.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37

Notes

IAS 36 states that “the impairment loss is the amount by which the carrying amount of an asset or cash-generating unit exceeds its recoverable amount”.

(FIFA, 2016) Article18; (FIGC, 2014) Article 28.

IASB tried to limit as much as possible the discretionary nature of the capitalization of intangible items, especially those which appear extremely uncertain not only the assessment but the very existence, at least according to the requirements now identified.IAS 38 says: “(..)Examples of directly attributable costs are: (1) costs of employee benefits (as defined in IAS 19) arising directly from bringing the asset to its working condition; (2) professional fees arising directly from bringing the asset to its working condition; and (3) costs of testing whether the asset the asset is functioning properly (..)”

(FIFA, 2016) Article10

IAS 38.97

In case of a purchase of a football player at the end of his career, it is advisable to proceed with an “accelerated method” with decreasing instalments because the club has higher possibilities to exploit the professional performances in the first years.

IAS 36 seeks “to ensure that an entity's assets are not carried at more than their recoverable amount”.

IAS 36.6 specifies that a CGU is “the smallest identifiable group of assets that generates cash inflows that are largely independent of the cash inflows from other assets or groups of assets”.

For example, during the summer transfer window Real Madrid bought the Colombian footballer James Rodriguez for an amount of approximately €80 million. After only two days from the purchase, however, Real Madrid sold 345,000 jerseys with the number and the name of the Colombian football player gaining approximately €33.4 million (Euromericas, 2014). To date, there are several football teams that make signing a double contract to their football players, one tied to the exploitation of sports performance, the other regarding the exploitation of image rights.

IAS 36.70: “If an active market exists for the output produced by an asset or group of assets, that asset or group of assets shall be identified as a cash-generating unit, even if some or all of the output is used internally. If the cash inflows generated by any asset or cash-generating unit are affected by internal transfer pricing, an entity shall use management’s best estimate of future price(s) that could be achieved in arm’s length transactions in estimating: (a) the future cash inflows used to determine the asset’s or cash-generating unit’s value in use; and (b) the future cash outflows used to determine the value in use of any other assets or cash-generating units that are affected by the internal transfer pricing”.

(A.S. Roma, 2015) “When there are some impairment indicators of multiannual rights to exploit performance of footballers [...] an assessment is made to determine the recoverable amount. In cases where by the impairment test emerges a permanent loss of value, the asset is written down”.

(Red Football limited, 2016), p. 27 specifies: “Management does not consider that it is possible to determine the value in use of an individual football player in isolation as that player […] cannot generate cash flows on his own”.

(Tottenham Hotspur, 2016), p. 13: “The Group does not consider that it is possible to determine the value in use of an individual football player in isolation as that player […] cannot generate cash flows on his own. Furthermore, the Group also considers that all the players are unable to generate cash flows even when considered together”.

(Norwich City Football, 2016), p. 19: “The Directors assess whether, at the period end, players are available for selection to play for the Club. In circumstances where it is apparent that the player would not be available to play for the Club and has not yet been sold (e.g. fallen out of favour with senior football management or suffered a career threatening injury), that player is valued on a “recoverable amount” basis which is based on the Directors’ best estimate of his valuation at the next available transfer window. Any resulting impairment charge is recorded within operating expenses”.

To be more accurate, (FIGC, 2009) states that the review of the residual value of the rights of the player incurred must be made by the companies even if the injury is not so serious as to configure the immediate abandonment of activity by the player, but of entities, however, that would result in uncertainty as to the recoverability of the value of the right.

(Birmingham, 2015), p. 17: “In certain instances, there may be an individual player or group of players whom the club does not consider to be part of the First Team squad and who will therefore not contribute to the future cash flows earned by the cash-generating unit. This is normally due to […] planned sale for proceeds below carrying value. In this situation, […] these players will be assessed tor impairment in isolation by considering their carrying value with the club's best estimate of their lair value less costs to sell”.

In addition to the item “Football team performance”, there are the items: “Cash generating unit”, “Budget period”, “Discount rate” and “Growth rate”.

(FIGC, 2016), p. 21 specifies that: “the data presented are based on an average of the last 5 years’ results to avoid distortions caused by the different specific importance of the football club (sports history, catchment areas and so on). They have been taken into consideration the consequences of participating or not in European competitions and promotions and relegations.”

Moreover, the production value of a company that qualifies to Champions League without the previous year has qualified for the Europa League is growing by an average of €54.4 million.

IAS 38.12

(FIFA, 2016) Article 15: “An established professional who has, in the course of the season, appeared in fewer than ten per cent of the official matches in which his club has been involved may terminate his contract prematurely on the ground of sporting just cause. Due consideration shall be given to the player’s circumstances in the appraisal of such cases. The existence of sporting just cause shall be established on a case-by-case basis. In such a case, sporting sanctions shall not be imposed, though compensation may be payable. A professional may only terminate his contract on this basis in the 15 days following the last official match of the season of the club with which he is registered”.

At the contract’s expiry date, a footballer is declared free agent and he can accept a contract offered by another team. The players can sign an initial agreement with another club 6 months before his current contract ends. The buyer club will not pay any transfer fee.

IAS 16 specifies that the exchanges are valuated at fair value when the fair value is measurable reliably.

For example, SSC Napoli (Italy) uses the amortization in decreasing instalments. These are the percentages for every kind of contract signed with its players:Quinquennial; 40% the first year, 30% the second, 20% the third, 7% the fourth, 3% in the fifth.Quadrennial: 40%-30%-20%-10%.Triennial: 50%-30%-20%.Biennial: 60%-40%.Annual: obviously the 100% recorded in the current year.SSC Napoli’s method represents an unicum in Serie A and it applies ITA-GAAP.

UEFA allows clubs to adopt the expensing policy too.

IAS 36.6 states the definition of “recoverable amount”, “fair value” and “value in use”.The Recoverable amount is “the higher of an asset's fair value less costs of disposal (sometimes called net selling price) and its value in use”.The Fair value corresponds to “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date”. The Value in use is “the present value of the future cash flows expected to be derived from an asset or cash-generating unit”.

IAS 36 states that “Recoverable amount should be determined for the individual asset, if possible. If it is not possible to determine the recoverable amount (fair value less costs of disposal and value in use) for the individual asset, then determine recoverable amount for the asset's cash-generating unit (CGU)”.

In the ANNEX VII “Basis for the preparation of financial statements”, letter C “Accounting requirements for player registrations”, UEFA states that “All capitalized player values must be reviewed individually each year by management for impairment”.

(Juventus, 2016) “When there are some impairment indicators of the multiannual rights to exploit performance of footballers [...] the write-down (Impairment) of the residual value is made”.

Accounting Recommendation N.1, letter C.III states: “If a football player under contract decides to quit the agonistic activity, the company, in accordance with the general principle of residual useful life, must impute to the income statement as depreciation of the related asset, all part of the cost not amortized, as it has failed the ability to generate future economic benefits by the footballer.A similar write-down of the net carrying value of the right, to be charged to the Income Statement, must be carried out because of a serious injury suffered by the player who forces him to abandon the agonistic activity. It notes that, compared of such cost, the company should recognize the rights recognized (gains) arising from insurance compensation. It should be noted that the review of the residual value of the multiannual rights to exploit the performance of the footballer must be made by the companies even if the injury is not so serious as to configure the immediate abandonment of activity by the footballer, but severe enough, however, to determine uncertainty regarding the recoverability of the value of the player”.

(Arsenal Holding PLC, 2016), p. 45 indicates: “Whilst no individual player can be separated from the income generating unit, which is represented by the playing squad and the football operations of the Group as a whole”.

(Birmingham, 2015), p. 17: “The club calculates the value in use of this cash-generating unit by discounting estimated expected future cash flows relating to the club activities and compares this value with the value of the intangible assets, stadium and training facilities (including related assets). Il the expected future cash flows are below the recorded value of assets the club will make an impairment of assets on a pro-rata basis”.

For further details, see IAS 36 paragraph 12.

(Rangers International Football Club PLC, 2016), p. 36: “The Group considers that the only cash generating unit is the operation of the football club. All income, costs and associated cash flows from retail operations are excluded from the impairment review. Individual player registrations are included within the cash generating unit unless there are circumstances arising that would exclude them from the playing squad (such as sustaining a significant long term injury). In such circumstances […] (the player) is then assessed for impairment in isolation”.

(Rangers International Football Club PLC, 2016), p. 34: “The estimated cash flow is based on the Group’s forecasted results and margins, including the necessary capital expenditure to meet anticipated performance. The assumptions used represent Management’s best estimate and are based on past experience and internal information held by the Group.”

(FIGC, 2016), p. 21 specifies that: “the data presented are based on an average of the last five years’ results to avoid distortions caused by the different specific importance of the football club (sports history, catchment areas and so on). They have been taken into consideration the consequences of participating or not in European competitions and promotions and relegations.”

Instead FIGC (2014), in Italy, although does not refer to IAS in its accounting recommendations, believes that an impairment loss should not be maintained in the balance sheet when there are no more reasons that have led to carry the loss. The book value, therefore, must be restored at net of additional depreciations that have not to be calculated because of the previous write-down.

References

A.S. Roma. (2015) Relazione finanziaria annuale. A.S. Roma: Roma, Italy.

Amir E and Livne G (2005) Accounting, valuation and duration of football player contracts. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting; 32 (3–4): 549–586.

Arsenal Holding PLC. (2016) Statement of accounts and annual Report 2015/16. London.

Biancone PP and Solazzi A (2012) Financial communication in professional football clubs. Economia Aziendale Online; 3 (1): 153–174.

Birmingham FC (2015) Report and Financial Statements. Annual Report. Birmingham.

Duque J and Abrantes Ferreira N (2005) Explaining Share Price Performance of Football Clubs Listed on the Euronext Lisbon.

Euromericas. (2014) Real Madrid sell 345,000 James Rodriguez replica shirts in 48 hours.

FIFA. (2016) Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players.

FIGC. (2009) Raccomandazioni Contabili.

FIGC. (2014) Norme Organizzative Interne della F.I.G.C.

FIGC. (2016) Report Calcio 2016.

Fiori G (2003) La valutazione dei diritti pluriennali alle prestazioni degli sportivi professionisti: una possibile metodologia. Rivista Italiana di Ragioneria ed Economia Aziendale; 103 (7/8): 314–330.

Gelmini L (2014) Le società di calcio professionistiche nella prospettiva dell'economia d'azienda. Modelli di bilancio e valore economico dei club. Giuffrè editore: Torino.

Juventus FC (2016) Relazione finanziaria annuale. Football Club: Torino, Italy.

Kulikova LI and Goshunova AV (2014) Human capital accounting in professional sport: Evidence from youth professional football. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences; 5 (24): 44.

Lozano FJM and Gallego AC (2011) Deficits of accounting in the valuation of rights to exploit the performance of professional players in football clubs. A case study. Journal of Management Control; 22 (3): 335–357.

Mancin M (2009) Il bilancio delle società sportive professionistiche. Normativa civilistica, principi contabili nazionali e internazionali (IAS/IFRS. CEDAM: Padova.

Marotta L (2014) Bilancio FC Barcelona: un'equilibrata gestione economica porta al terzo utile consecutivo.

Morrow S (1997) Accounting for football players. Financial and accounting implications of ‘royal club liégois and others V Bosnian’ for football in the United Kingdom. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting; 2 (1): 55–71.

Morrow S (1999) The New Business of Football. Accountability and Finance in Football. Palgrave Macmillan: London.

Morrow S (2003) The Peoples Game? Football Finance and Society. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, United Kingdom.

Morrow S (2006) Impression management in football club financial reporting. International Journal of Sport Finance; 1 (2): 96–108.

Morrow S (2013) Football club financial reporting: Time for a new model? Sport, Business, Management: An International Journal; 3 (4): 297–311.

Norwich City Football. (2016) Annual Report. Norwich.

Oprean VB and Oprisor T (2014) Accounting for soccer players: Capitalization paradigm vs. expenditure. Procedia Economics and Finance; 15, 1647–1654.

Pavlović V, Milačić S and Ljumović I (2014) Controversies about the accounting treatment of transfer fee in the football industry. Management: Journal of Sustainable Business and Management Solutions in Emerging Economies; 19 (70): 17–24.

Pinnuck M and Potter B (2006) Impact of on-field football success on the off-field financial performance of AFL football club. Accounting and Finance; 46, 499–517.

Rangers International Football Club PLC. (2016) Annual Report. Glasgow.

Red Football limited. (2016) Annual report and financial statements. Manchester.

Reilly T and Gilbourne D (2003) Science and football: A review of applied research in the football codes. Journal of Sports Sciences; 21 (9): 693–705.

Relvas H, Littlewood M, Nesti M, Gilbourne D and Richardson D (2010) Organizational structures and working practices in elite European Professional Football Clubs: Understanding the relationship between youth and professional domains. European Sport Management Quarterly; 10 (2): 165–187.

Rowbottom N (2002) The application of intangible asset accounting and discretionary policy choices in the UK football industry. The British Accounting Review; 34 (4): 335–355.

Tottenham Hotspur. (2016) Annual Report and Financial Statements. London.

UEFA. (2012) Club licensing and Financial Fair Play regulations 2012. UEFA: Geneve, Switzerland.

UEFA. (2015) Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play Regulations. UEFA: Nyon, Switzerland.

UEFA. (2016) Distribuzione ricavi UEFA Champions League.

Vernhet A and Augè B (2010) Professional Players: Specific Intangible Assets. EASM: Prague, Czec Republic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Maglio, R., Rey, A. The impairment test for football players: the missing link between sports and financial performance?. Palgrave Commun 3, 17055 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.55

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.55