Abstract

This article examines how women managers in the maritime sector in Eastern and Southern Africa perceive the meaning of “success” in their careers and how their work impacts on their lives. Eastern and Southern Africa have experienced the highest economic growth of the sub-African regions in the last few decades. As the majority of these countries are either coastal states or islands, the role of the maritime sector is large, contributing significantly to boosting the local economies. Despite the sector’s traditionally male-dominated work environment, some women have reached managerial positions and have performed as remarkably as their male counterparts. However, this study highlights that to be successful in their maritime careers, women managers tend to live a work-led life rather than one that is work-life balanced. There is a lack of research on the work-life balance of the women labour force in Eastern and Southern Africa, particularly in the maritime sector. Here, a phenomenological method was adopted in which a survey was conducted to address this gap. A total of 45 responses were analysed to identify the challenges that Eastern and Southern African women managers are facing in the maritime sector today. Interviews were also carried out to further understand the meaning of career success to these women professionals engaged in the maritime sector. Although opportunities for women to participate in the formal economy have increased as a result of rapid industrialization in the regions, women are still expected to carry out the majority of domestic jobs associated with their traditional gender roles. The research concludes that the lack of a work-life balance model failed to increase women managers’ agency within the “man-made” system of the maritime industry. Given the particularities of each country, which impact on the actual realization of these women’s aspirations, the article also acknowledges the importance of targeted capacity-building programmes by the International Maritime Organization for women at a regional and international level. This article is published as part of a collection on the role of women in management and the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

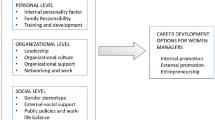

Transport sectors are generally male-dominated around the world, and the maritime industry, in particular, conforms to this trend. Women seafarers represent only 1–2% of the total seafaring workforce around the world (Belcher et al., 2003). Seafaring knowledge and experience are often highly appreciated in shore-based positions in the maritime industry. The fact that only few women have seafaring or relevant work experience has posed a challenge for women to be successful in their career development in this sector. For the few women who have reached managerial positions at work, their success in surviving in a man’s world seems to be dependent on various parameters, namely, the prevailing working environment, the attitudes of male counterparts, and continuous professional development programmes.

Limited research has been carried out on the experience of women managers in the maritime industry, which includes case studies in the Caribbean (Grant and Grant, 2015), Greece (Pastra et al., 2015), and the United Kingdom (Mackenzie, 2015). Literature on female maritime managers in Eastern and Southern Africa can hardly be found, despite the fact that there are large networking associations of maritime women managers that exist in the regions. Members of the Women’s International Shipping and Trading Association (WISTA) number over 2,000 in 33 countries (Orsel, 2015), many of whom are in managerial positions in the shipping industry. WISTA’s membership in Eastern and Southern Africa is, however, limited to South Africa. An all-encompassing network for maritime women managers in these regions would be the Association of Women Managers in the maritime sector of Eastern and Southern Africa (WOMESA), established in 2007 as part of the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) regional support network. This regional network for women in the shipping industry has been active in promoting women in the maritime sector through advocacies and associated activities.

Eastern and Southern Africa have experienced the highest economic growth of the sub-African regions in the last few decades (AfDB, OECD, UNDP, 2015), leading to significant empowerment of women in these regions. As such, the important role of women in the industry and trade has been increasingly felt (Brenton et al., 2013). On the other hand, the maritime industry is still heavily male-dominated, with technical knowledge, including seafaring experience, contributing to the success of male managers. Since fewer women study Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics subjects, women are often regarded as being less capable than their male counterparts, despite their potentials (Mackenzie, 2015). To challenge such gender stereo-types and prove their competence at work, women managers’ commitment to work is extremely high. While climbing the career ladder amidst a male-dominated work environment, how do women managers in the maritime sector perceive their “success” and how does it impact on their lives? This study sheds light on the case of maritime women managers in Eastern and Southern Africa, where economic development has been booming in recent years.

Economic development and women in Eastern and Southern Africa

The countries in the Eastern and Southern Africa regions vary in terms of their situational context. The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) forms a free trade area with 19 member States, including the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, and Ethiopia), North Africa (Egypt, Libya, and Sudan), the Indian Ocean islands (Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles), the African Great Lakes (Burundi, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, and Uganda), Southern Africa (Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe), and Central Africa (Congo). COMESA is the second largest economic community in Africa, next to the African Economic Community (AEC), in terms of its total area and population. Similarly, much importance is laid on the economic and trade element of the regions by the European Union, represented by 11 countries from the Indian Ocean islands (Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles), the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan), and Southern Africa (Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) (EU, n.d.). On the other hand, WOMESA draws its members from 24 countries, namely, Angola, Botswana, Burundi, Comoros, Kenya, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The sample for this research was drawn from the network of WOMESA to examine how its members perceive “success” and how it impacts on their lives.

According to the annual report by COMESA (2014), East Africa has benefited from new oil and gas discoveries in the region and the resulting increase in investment in its transport infrastructure. Southern Africa has experienced incremental growth as a whole. Such economic development and infrastructure investment are nevertheless often led by men who are in decision-making positions. The countries in Eastern and Southern Africa show an apparent gap in terms of women’s participation in the economy and labour market, income levels, as well as in management (World Economic Forum, 2015).

On the basis of the participants’ profiles in this study, the gender gap indexes of selected countries are shown in Table 1.

In these indexes, the highest score is 1 (equality) while the lowest score is 0 (inequality). For instance, in the index of economic participation and opportunity, Malawi scores 0.809 (ranked 12th) and Mauritius 0.534 (ranked 127th). Malawi and Mozambique are relatively high in global ranking; however, the related data for legislators, senior officials, and managers (the right column) were not on record. Notwithstanding the relatively high participation of women in the labour force in the selected countries (0.89 on average), the parity index for the leadership and management level involvement of women (that is, as legislators, senior officials, and managers) is considerably lower (0.33 on average). The major concern is that some countries, like Djibouti, Seychelles, and Somalia, carry no data to allow any comparison at the regional and global level. As a result, it becomes difficult to gauge the status of gender equality in these countries.

Career success

In the business world, “success” is commonly associated with high status, high remuneration, and awards and prizes, among other achievements. This notion of “success” that has been established in a man’s world has greater significance for women managers because of the glass ceiling that hinders women’s access to various opportunities (ILO, 2015). In addition, the meaning of “success” to women varies and can be measured in various ways (Bostock, 2014). Though by no means all, many women have successfully managed both work and family. Mrs. Irma T. Comia, a Filipino administrative clerk who works on board ships, is one such example. Her “successful career” story was featured in a business magazine to highlight women’s achievement in both work and life.Footnote 1 The media sometimes treats such “super women” as role models, because they achieve their career success while fulfilling women’s gender roles in the home.

Determining the interpretation of “success” for anyone is extremely difficult. With a variety of contracts and employment patterns, a broad interpretation of a “successful career” has been embraced. The increasing segmentation of professional labour markets in both formal and informal employment affects women’s work patterns, and the meaning of career “success” needs to be re-constructed in different contexts.

Women’s career success

The study by Enke and Ropers-Huilman (2010) categorized the perception of “success” for working women into five themes: success is subjective and internally defined; success involves finding a balance between work and family; success involves contributing to a community; successful women are goal-oriented; and successful women do not impede their own success. Their research indicates that “success” is subjective and involves balancing work and family. It is also important for “successful” women to feel that they are contributing and making a difference in their communities. Similar ideology was noted in a study conducted at the University of Cambridge (Bostock, 2014), which confirms that “success” is subjective and internally defined, and that finding a balance between work and family as well as making a contribution to one’s community are important.

Women’s career “success” may include the phase of “setbacks” at work. This often involves major personal life events, such as childbirth, a new relationship, relocation, a caring role for elder family members, and an illness or death in the family. These changes around women affect their self-defined success and they tend to find less time to devote to and an inability to advance their career (Kalet et al., 2006). The “interruption” phase is also noted in the ILO’s (2013) career development model for women workers in transport industries, including the maritime sector. Though such an interruption in women’s career results in them slowing down or sometimes temporarily placing their career progression on hold, many women are still highly capable of recovering lost ground in achieving self-defined success in life (Kalet et al., 2006).

In discussing career “success” and “progress”, it is important to separate the personal success of individual women from progress for women in society as a whole (Greed, 1994). In other words, women’s career “success” depends both on their individual perception of “success” and societal change, including “progress” in gender equality, requiring scientific reviews to evaluate how far progress has been achieved. Women’s expectations are evolving (Ashburner, 1994); however, the pattern of participation of women in management, and more specifically at the decision-making level, seems to be less progressive in the maritime sector compared to any other sector. In relation to stereo-typical perceptions of gender difference, we need to understand how the gendered nature of management work is constructed.

Are women managers competent? The questioning of professionalism

The division of labour by occupation has existed since ancient times. However, more specialized knowledge and skills are becoming emphasized in modern societies. By gaining competence in specific areas of work, people are able to build a relationship of trust with their clients and co-workers as they share common values and expectations about what their professional work entails. The labour market also determines its price and may attribute a certain status or grade to categories of jobs.

The problem with women entering the management level in the labour market is that those management positions are mostly occupied by men and highly remunerated because of their high responsibilities with regard to assignments. When women enter this territory, they may not automatically obtain the same degree of trust for their work that the market dictates. This problem can happen even before the work commences: the client may make a judgment without seeing the result of the work. As soon as there is a failure to establish trust in jobs and the promise of successful delivery of work is doubted, the professionalism of women managers is questioned. Women sometimes systematically fall into this trap of being stigmatised because of gender. They are often found in clerical and assistant jobs in workplaces, and this landscape can endorse the stereotypical view of women managers as less competent.

In addition to this common prejudice about women managers, the maritime sector carries a shared work culture. For example, in shipping companies, some managerial positions are often occupied by ex-captains or those who have spent a considerable amount of time in their career at sea. They will bring their values, which reflect masculine norms and values, from the occupational culture of seafaring to the job (Kitada, 2010, 2011). In fact, many of these male ex-seafarers are not used to working with women, who are in the extreme minority on board; consequently, their behaviour towards women in shore jobs can be seen as inappropriate. They can be overtly discriminating to women in the office or show distrust towards them. It is not, therefore, easy for women managers to be professionally acknowledged by their male counterparts. Ex-seafarers can maintain their own pride at work by differentiating themselves as survivors at sea from the rest of the shore-based workers, who have never explored such adventures as “true men”. Ex-seafarers tend to make their own “club” to share their common values and experiences, in which many women are not often able to participate. Such a work practice narrows and limits the idea of maritime professionalism. In today’s globalized economy, can this be the way forward?

Indeed, the concept of professionalism has evolved over years in organizational contexts. For example, more and more shore-based maritime organizations rely on human resources with non-maritime backgrounds, such as law, economics, business, and procurement, which may be considered as better suited for a management position. Unlike the last century, it is hard to find professional practitioners who have worked on board ships for many years before joining a shore-based managerial post because of the shortage of qualified officers worldwide as well as the unpopularity of seafaring jobs among the younger generation (BIMCO and ICS, 2016). In this scenario, women have received more attention as potential human resources to supply the needs of the maritime industry, though their acceptance at work does not seem to have progressed correspondingly. Many women who enter the maritime industry tend to lack certain technical backgrounds, which is often seen as their drawback.

Women as maritime human resources

Gender equality has been reported to lead to better human development results for future generations in Bangladesh, Brazil, Côte d’Ivoire, Mexico, South Africa, and the United Kingdom (World Bank, 2011). The same report also presents evidence that women are an important human resource. In South Africa, for example, as women’s share in household earnings has increased, so has their control over key household decisions. Similarly, in Malawi, fairly small cash transfers to girls have been found to increase secondary school enrolment and reduce dropout rates. McGinn et al. (2015) further confirm this account in their recent study of daughters of working mothers, who were found to be more likely to be employed, receive higher earnings, and hold supervisory roles in the 24 countries they investigated.

In the maritime sector, the global initiative led by the IMO began in late 1989. The Programme for the Integration of Women in the Maritime Sector aimed at encouraging its member States to open doors to women in the shipping industry (Tansey, 2015). At that time, there were only a limited number of maritime education and training institutions around the world that accepted female students to enrol in navigation and/or engineering courses. Today, more institutions provide access for women to study maritime subjects, though the number remains small. Yet, the actual employment of women in the maritime sector has not improved in scale. For women seafarers, their training will not be completed only in school, as it is mandatory under the STCW Convention2 that they work on board for 12 months as cadets to obtain their international licence. Since many shipping companies are still reluctant to take female cadets on board and can find male cadets without problem, some women are stuck between education and employment.

Women managers in the maritime sector are confronted with cultural barriers in a man’s world that make their professional ability invisible in organizations. They consequently feel compelled to work much harder than their male counterparts to receive recognition. This work-intensive pattern of career progression seems to be a barrier for women managers in the maritime sector to achieve work-life balance. In the face of social pressure for women to maintain their family’s well-being, this work-led life does not necessarily accord with their view of what “success” means in their professional careers. The question is what the appropriate level of work-life balance should be for women managers in the maritime sector.

The term “work-life balance” is often used in policy debates, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) emphasizes “the amount of time a person spends at work” as an important aspect of “work-life balance” (OECD, 2015). This relates to the issue of public health, as employees’ long working hours can increase stress and jeopardize safety. Generally, men work longer hours in OECD than non-OECD countries. For example, 17% of male employees work very long hours, compared with 8% of women (OECD, 2015). However, these figures simply look at paid work and ignore the unequal share of caregiving work between men and women that can be observed worldwide. ILO employs the term “work-family reconciliation” in accordance with the Workers with Family Responsibilities Convention, 1981 (No. 156). In modern society, “work-family reconciliation” deals with a series of new challenges including “the rise in women’s paid work, the growth in non-standard work, work intensification, ageing and changes in family patterns”, among others (ILO, 2011). Such issues are understood within a wider definition of the term “work-life balance” (ILO, 2011), a position this article likewise adopts in discussing the challenges of maritime women managers within the wider scope of socio-economic issues. The indicators of sacrifice are in terms of no marriages, late marriages or failed marriages, no children, children not properly taken care of, and family and friends being side-lined, among others. However, the exact nature of the socio-economic issues was not mentioned in the survey questionnaires. It was the follow-up interviews that allowed greater insight into the said issues. In addition, compared to the OECD countries, the societies of the Eastern and Southern Africa regions generally lack research on the work-life balance of the women’s labour force, particularly in the maritime sector. It is the aim of this article to draw on the perception of women managers in the maritime sector about their career success in relation to their familial role in the home.

Methods

A survey method was used for data collection to understand the relationship between the professional and personal lives of maritime women managers in Eastern and Southern Africa. A test survey was undertaken to finalize the questionnaire. This process was important to ensure that all the questions were appropriately set. The final questionnaire consisted of five multiple-choice and five open-ended questions to give more freedom to the participants to express their own thoughts.

The participants were recruited from WOMESA in early 2016. To increase the responses, a survey was prepared in two formats: paper-based and online surveys. A total of 45 responses were collected for analysis. The majority (n=41) replied through the paper-based survey, while only four returned their responses through the online survey. The participants’ countries were Ethiopia (n=6), Mauritius (n=6), Kenya (n=5), Tanzania (n=4), South Africa (n=4), Malawi (n=1), Madagascar (n=2), Mozambique (n=1), Seychelles (n=1), Djibouti (n=1), Somalia (n=1) and no answers (n=13).

Both quantitative and qualitative research methods were employed in the preliminary survey. The hypotheses were created to investigate the perception of maritime women managers about their career success. The SPSS statistics software package was used for statistical analysis.

After the preliminary survey data analysis, for clarity and to avoid any misinterpretation of data, interviews were conducted for in-depth narratives and detailed accounts on the experiences of the maritime women managers, which included their perception of career success and their emotions and feelings towards balancing work and life. Informed consent was given by the interviewees before the interviews. To respect the participants’ wishes, none of the interviews were recorded; hence, field notes were taken during and after the interviews (Mack et al., 2005). More emphasis on qualitative methods such as interviews is known as a feminist methodology (Maynard, 1994).

Results

The interpretation of “success” by the women participating in this study was subjective, as relayed through the accounts of their individual work experience. Eastern and Southern Africa vary widely in terms of their fragility, insecurity, cross-border conflicts, governance challenges, as well as cross-cutting issues related to gender, the environment and climate change (AfDB, 2011). On the other hand, certain similarities in women’s economic development have been observed throughout the regions. As WOMESA has been working on the common goal of empowering women in the regions for almost 10 years, exploring a shared set of gender-related issues is valid in this case. The particular relation between theory, practice and research will be shaped by the context in which these are located (Rule and John, 2015). It is therefore appropriate to look into women’s experience in maritime careers on similar professional grounds.

Preliminary results

To analyse the input of the participants drawn from a spread of contexts, the phenomenological approach (Moustakas, 1994) was adopted to identify key issues in terms of their career success. Fifty percent of the respondents perceived their experience as maritime women to be quite tough as they had to work harder to affirm themselves. This, in turn, was to the detriment of their individual sense of self and, eventually, their family life. The remaining fifty percent who climbed the ladder in spite of the odds seemed to have enjoyed the experience and described it as being fulfilling. Overall, the majority of the respondents agreed that a maritime career is a challenging journey. Irrespective of their socio-economic background, their reported experiences as maritime women managers unfurled a number of similarities in terms of lack of recognition for their contributions, acceptance as maritime women leaders, and underlying financial and non-financial cost implications. The differences related to the availability of in-house support systems at the work place and within the family.

Another potentially important preliminary finding is that the women who averred achieving work-life balance were from the countries experiencing high economic growth. According to the OECD (2012), the economic empowerment of women is a prerequisite for sustainable development, pro-poor growth, and the achievement of all the Millennium Development Goals. Likewise, economic development plays an instrumental role in addressing the perpetuation of inequality between men and women (Duflo, 2012). Indeed, the women managers stemming from countries experiencing high economic growth asserted that they benefited from flexible working hours, day care facilities for children at the work place or within the vicinity, spousal support, extended family support and the employment of domestic helpers at home. This remains a critical result as all respondents firmly believed in family as an institution. Family is deemed to offer a small frame for socio-economic development. As such, cumulative small frames make up the larger structure of society. Family and parenthood were highlighted as fundamental roles of human beings towards the sustainable development of society as a whole.

The challenges faced by maritime women were broadly classified under three main themes. The first challenge is the inherent nature of the sector, which is predominantly the preserve of their male counterparts. We observed that associated challenges of struggling were often found in other male-dominated sectors, such as fire-fighters (Yoder and Aniakudo, 1996), army women (Pettersson et al., 2008), and police women (Holdaway and Parker, 1998). The male-dominated work environment also supports work-oriented lifestyles, which makes it difficult for some women to strike a balance between their work and social life. Sixty-seven percent of the respondents felt that there was no work-life balance. The main reasons were reported to be self-prejudice based on their inferiority complex vis-à-vis their male counterparts. The deep-seated inclination to go the extra mile to affirm oneself as a maritime professional often resulted in more time being devoted to the same work than that which would have been devoted by male counterparts (Bostock, 2014).

Secondly, a persistent lack of recognition for their contribution to the development of the sector was observed. The experience shared by the maritime women managers was clearly detailed by Wendy Pullan (Bostock, 2014):

“Women also talked about how their ‘voice’ was heard—or not—in the various organisations for which they had worked. There was reference to being described as anything from shrill, stroppy and hysterical through to frivolous and chatty. There were also examples of feeling voiceless in meetings where they were often in a minority to start with: they didn’t get space to speak, colleagues talked over them or a male peer was given credit for a point they had raised. An absence of voice also related to the lack of female representation at certain levels and on particular bodies”.

The financial implications of maritime women attaining managerial positions were not emphasized in view of the significant number of fellowships available for the advancement of women in the sector. In fact, more emphasis was laid on the costs in terms of extra time and energy having to be deployed to live up to the acquired positions. This, in turn, had a spill-over/multiplier effect on the other aspects of the lives of the maritime women managers. In addition, the respondents affirmed their perception that there was no cost to society, and if ever there were such costs, they were actually positive ones. Nevertheless, ensuing discussions on the written replies revealed that their responses were, in fact, subjective. Late marriages, divorces, or single parenthoods were a common incidence among maritime women pursuing their careers. During their career progression, maritime women managers at times tend to neglect some perceived fundamental duties at both the familial and social level, including childcare, looking after the needs of the family, socialization, and domestic duties. They averred that men should be encouraged to care and support women in their endeavours.

Thirdly and ultimately, capacity building is key to increasing the opportunities for women in the maritime sector in the regions. In this respect, the role of the International Maritime Organization and the training institutions operating under its aegis is commendable. For instance, an annual WOMESA regional conference is organized by IMO for capacity building in alignment with the objectives of WOMESA to actively support the advancement of women to managerial and higher levels in the maritime sector. This is a good example of partnership between an international organization and an NGO. Surprisingly, significant gaps were identified across the WOMESA member states in terms of policy measures and stance on the empowerment of maritime women. In countries like Somalia, Eritrea, Sudan and Djibouti, strategies for the empowerment of maritime women were reported to be quasi non-existent, while in countries like South Africa, Kenya, Seychelles and Mauritius, it was encouraged for maritime women to assume managerial and leadership positions. Training/Continuous Professional Development courses, fellowships, and exchange programmes promoted capacity building while retention strategies included in-house support systems, namely, entitlements such as maternity leave, flexible working hours, and childcare facilities. Mentorship programmes and networking were crucial in attenuating the resulting externalities.

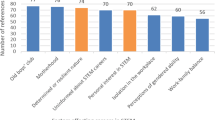

Understanding the career success of maritime women from quantitative data

Applying data mining techniques (Han et al., 2012) and SPSS to consider Eastern and Southern Africa as an integrated frame revealed additional insights on shared perceptions with respect to maritime women and their career success. To this effect, the age group was used for data categorization, as the research inquires into the relationship between career progression by number of years of working in the industry and the meaning of “success” as maritime professionals.

Acceptance as a maritime woman leader

The highest count of “No” for being accepted as maritime women leaders falls under the 30–40 age group, while the highest count of “Yes” for being accepted as maritime women leaders falls under the 50–60 age group. This result was consistent with ensuing discussions in the follow-up interviews. At the initial stage of their careers, women have to face the distrust of their employers with regard to their competence and ability to perform as maritime professionals. Over the years, their successive achievements were instrumental in stimulating a level of acquired acceptance as maritime women leaders.

The one-way analysis of variance was used to determine whether there were any significant differences between the age group factor and the dependent variable maritime woman leader. Table 3.

It is clear from the results of Table 2 that the data are not normally distributed as p is less than 0.001 and cannot thus assume normality. Therefore, to find the differences among the age group (as a factor), the Kruskal–Wallis method was used as the non-parametric test.

Since the p value is greater than 0.05 (p=0.105), we accept the null hypothesis that there are, in fact, differences among the mean for women leaders’ acceptance and that for the age groups. The leadership of their male counterparts is readily accepted at an earlier age (Bostock, 2014).

Belief in family as an institution and the perceived importance of parenthood

It can be clearly observed that all the participants believe in family as an institution as no respondents answered “No” to the question. The highest count of “Yes” for believing in family as an institution is the age group between 30 and 40 years old. The reason is likely to be two-fold: the most obvious one is that a major proportion of the respondents belongs to this age group; secondly, this is the typical age nowadays by which most women have seemingly achieved their academic career aspirations and look forward to settling down.

The highest count of participants who believe in the importance of parenthood falls under the 30–40 age group. The underlying reason is similar to the belief in the family as an institution. In addition, scientific research has shown that women’s fertility begins to decline in the late 20s with substantial decreases by the late 30s (Dunson et al., 2002).

Perceived cost to society

The highest count for “Yes” in terms of cost to society falls under the 30–40 age group, while the lowest falls under the 60 and above age group. This result is considered reasonable as the cost to society of women under 30–40 is higher in view of their persistent struggle to reconcile conflicting aims and interests in pursuit of their respective ends.

Using logistics binary regression (Table 4), the possible regression equation between cost to society (Y) and the following variables was calculated using SPSS: X1—Position; X2—Marital status (1—single); X3—Marital status (2—Married); X4—Age group; X5—Educational qualifications; X6—Women leader acceptance; X7—Work-life balance.

This regression model accounts for 91.1% change in cost to society (see Classification Table 2), which is greater than when using no model (see Classification Table 1 Block 0), which accounts for just 77.8%.

Alternatively stated, 77.8% of the respondents agreed that the cost to society was high. However, the cost to society was not merely a depiction of what is perceived costly based on individual experience. The actual cost is far more than it is believed, as illustrated through the regression model. On another note, it is worth mentioning that those who disagreed with the high cost to society (22.2%) tended to represent the age group between 40 and 50 as well as the one between 30 and 40. These age groups were likely to critically experience a variety of choices in their lives and to struggle over the prioritization of either work or family. Although fewer percentages of women managers expressed disagreement, it remains a question whether some women managers’ experiences might be far too complex to analyse the direct correlation to cost to society.

Correlation between cost to society and work-life balance

Using the χ2 test to examine the correlation between the cost to society and the above variables, there was found to be no significant relationship between cost to society and most elements, except for the item work-life balance (see Table 5). The correlation between cost to society and work-life balance indicated a significant positive relationship between cost to society and work-life balance. Alternatively stated, the larger the difference in the work-life balance, the greater the liability to society. The cost to society is both explicit and implicit. Explicit costs are the financial cost of maritime training. As with other professional courses, maritime training is costly. However, 64% of the respondents benefited from the targeted capacity-building programme of the IMO, reporting that had it not been for such positive intervention, they would not have been successful in doing their postgraduate degrees and moving upwards on their career ladder. There are alternatives that are forgone in pursuing one’s career, and the foregone alternative may not always be the second best. During the interviews, women shared experiences of marriages collapsing, parents and children growing apart, and drifting among family members, such that the choice of pursuing a career in the maritime sector, which was initially driven by the dual purpose of self-fulfilment and providing a better life to their loved ones, was no longer the source of happiness it once was!

Behind career success: qualitative analysis of maritime women’s perceptions

The quantitative analysis implies that women managers in the maritime sector tend to sacrifice their personal lives, especially with regard to their families who are behind the scenes of their career success. A statistical confirmation of understanding the work-life imbalance as a cost to society is useful, though the sample size is too small for generalization. This article aims to look beyond this quantitative affirmation, and the qualitative analysis of interview data is thus used to provide a further account of maritime women managers’ career success.

In the interviews, further discussions were held on achieving success in the maritime sector as a maritime woman leader. The participants generally described their careers as quite challenging but also very rewarding. The need to constantly prove oneself remained omnipresent and was deemed to be energy sapping at times. However, over time, by displaying the right capability and ability, respect from their male counterparts was duly earned and sustained.

The career progression of maritime women is challenging in terms of climbing to leadership positions. One of the respondents who had attained a high position in top management shared with us that she spent almost her whole life downplaying her feminine beauty as the people at work would be bowled over by her looks and underestimate her as a professional in the maritime sector. She spent years hiding herself as a woman and strictly focused on being perceived as a leader. Today, she claims that she is finally free from the guilt trap of being seen as a woman. The reason for this is that after years of practice, she is now known as a professional first, and the fact that she is a good-looking woman no longer undermines her authority as a professional. As mentioned earlier, the fact that she was pretty initially seemed to prompt generalized assumptions that she was either stupid or had reached the top because she had capitalized on her beauty. She also related that besides being a maritime professional, she was also a proud mother of five children. She had her children without going on maternity leave because she did not have the choice. She mentioned that her aspiration to reach the top was her own. She deemed it unfair to impose her choice on others, in particular, her husband and employer. She was of the view that if a woman chooses to value her career progression, she should not allow others the opportunity to put her down by saying that she is not a good mother because she is a hard-working woman or that she is unprofessional because she pays too much attention to family matters between jobs. She said that it was indubitably very tough but that she is happy that she could do justice on both fronts as one’s professional and personal lives both exist and co-exist. This was the result of willpower and the strong conviction that things may be difficult, but nothing is impossible.

Another respondent who had achieved a leadership position in this traditionally male-dominated sector replied that she was driven by the fact that in her country, women and girls were treated as second class citizens or a burden to society. As she grew up, she witnessed her mother’s pain repeatedly as society ceaselessly taunted her for giving birth to two daughters. She was determined from a very young age to prove to society that women were not a burden and girls were as smart and productive as boys. Her career progression in the maritime sector was not only challenging but also rewarding. Establishing herself as a professional at management level was considered the perfect way to bridge the gap and change the deep-seated prejudices of her people.

Role models were deemed to be critical, particularly, in moments of despair when faced with resistance from society in terms of socio-economic challenges in affirming oneself as a maritime woman leader. Such socio-economic challenges exist at all times but to different degrees in all societies in Eastern and Southern Africa, irrespective of the level of the country’s development. It appears that gender mainstreaming is primarily about bringing a change in perception, and the most challenging part is to bring a change in the perception of our female counterparts themselves. Maritime women managers need to succeed in both their professional and personal lives. One of the interviewees shared her opinion that we can dream and fulfil our ambitions; on the other hand, there is always a cost associated with this. She asserted that it was difficult to find a work-life balance, in the sense that you have to work hard at your workplace to prove yourself as a maritime professional, and you have to work hard at home to make up for lost time with the family. In the end, it is quite difficult to find a balance for yourself as a person, as this impacts on both your psychological and physical health. It is not always all roses.

In summary, the perceptions of women managers’ “success” in their maritime careers are different; however, their professional success comes at a cost to society, which they described in terms of family life. Even those who managed to do well in both lives because of their strong will and the level of support they received from those around them considered their work-life balance to be challenging. In some cases, respondents were more work-oriented, while in other instances they prioritized their family life. Indeed work-life balance does not represent a short-term goal but rather a long-term process of making sense of their “success” in their lives.

Discussion

The overall data analysis highlights several issues of relevance. Firstly, it determines that the maritime women managers perceived “success” in terms of recognition for their competence in fulfilment of their duties. However, it also came out that the recognition being sought is not a given for these competent maritime women leaders. The demonstration of their competence is not enough to secure recognition. It has to be earned. Achieving “success” in this traditionally male-dominated sector is derived at a cost. Financial implications exist but are not a core deterrent in pursuance of career progression. The financial implications were significantly curtailed by opportunities to secure sponsorship based on gender policies to integrate women in mainstream maritime activities. The primary reason advanced to this end was the considerable support in terms of fellowships, full sponsorship, sponsored training, and fully-funded capacity-building programmes that the shipping industry had put at the disposition of potential maritime women leaders as productive human resources. The deterrent came at times when potential maritime women managers had to forgo such opportunities as a result of having to look after their young children or spouse.

The cost that raised much concern was the cost to society. The cost to society started with the persistent need for maritime women to go the extra mile to be respected as a maritime professional. This lack of recognition triggers a vicious cycle. By actively pursuing a maritime career, young maritime women set to become future leaders were often found to neglect the family as an institution by either opting for late marriages or not marrying at all. These cumulated individual crises on the personal front ultimately impact on society at large.

The positive relationship between cost to society and work-life balance also illustrates that a conducive work environment is likely to result in a positive impact on society. This was confirmed by the positive experiences shared by the respondents from countries enjoying a high economic growth rate, since economic development promotes women’s empowerment, and women’s empowerment contributes to high economic growth (McKinsey Global Institute, 2015).

The research highlights the positive contribution of maritime women managers but often at a cost in terms of late marriages, failed marriages or no marriages, children not properly taken care of or no plans to have children, and family and friends being side-lined, among other things, while leading a work-led life. The collapse of the family as an institution affects not only family members but also the nation. A growth in unmarried mothers and divorces has led to an increase in single-parent families, which is viewed as a liability to society (Vitz, 1999). For instance, it has been found that educated women are likely to delay their family planning, hence contributing to fewer children being born in the country and a loss of the state’s assets. Such opinions emphasizing women’s reproductive role as their primary and ultimate contribution to social sustainability do not liberate women from domestic roles in a patriarchal system, where women are subordinate to men. Feminists have been arguing that women are not the social slaves of their own country and should be affranchised from that notion. The current situation in the Eastern and Southern African maritime sectors, where women’s economic empowerment appears to represent a social cost, should be a matter of concern for policy makers.

In addition, the in-depth analysis of the survey questionnaire coupled with the ensuing interviews of respondents allowed a glimpse at the root cause of the key concerns being experienced by the women managers in the maritime sector. In the shipping industry, women leaders have no qualms in pursuing their ambitions but also believe that striking the right work-life balance is a must, not only for themselves as individual women, but also as members of a society in which women play various gender roles. Even if they are professionally successful, their “success” could include “double success” both at work and in the family. Policymakers should therefore be encouraged to create a more conducive environment for women to work in so that they are able to achieve a greater work-life balance and ultimately create a virtuous circle of development by reducing or even eliminating any arising cost to society.

Conclusion

This study depicts the issues that women managers must overcome in pursuit of their career in the shipping industry. The results of the survey show that the prevailing socio-economic environment of a country impacts on the evolving maritime women and their understanding of the meaning of “career success”. Male-dominated workplaces such as the maritime sector present similar challenges to women workers. In the case of women managers or leading personnel, the lack of recognition for their contribution to the development of the sector appears to be one of the critical issues to be addressed. Capacity building was also noted as an important issue to increase the opportunities for women, such as training and mentoring, in the maritime sector in the regions.

This study employed both quantitative and qualitative data analyses. For the quantitative research method, several statistical tests were conducted to examine whether work-life balance has something to do with women managers’ perception of “career success”. The view was confirmed that maritime women managers experienced the decision to climb up the ladder in a man’s world as a hindrance to maintaining work-life balance. Qualitative interview research methods were used to obtain deeper insights. Overall, maritime women managers in Eastern and Southern Africa believe that family is an important institution, which hence influences their individual perception of career “success”. Some women may feel lost in success if they sacrifice their family life. Though marriage and child-rearing are choices for maritime women, there seems to be a perception that women who are successful at both work and life are capable and respected. To support women managers in the maritime sector at the policy level, the research indicates that policymakers should consider creating a more conducive working environment for women to support them in achieving a greater worklife balance and thus reduce the cost to society.

The limitation of this study is its number of participants. To scale up the claims made by women, the participation of more women in research could help to improve the reliability of the statistical analyses. In addition, the use of other qualitative methods, such as focus groups, can be further explored. If more data are obtained from each country, a comparative analysis between countries may also be possible.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because of the nature of the subject under investigation and the willingness of respondents to answer the questions subject to confidentiality being respected. The datasets are available in anonymous formats from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Bhirugnath-Bhookhun M and Kitada M (2017) Lost in success: women’s maritime careers in Eastern and Southern Africa. Palgrave Communications. 3:17023 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.23. Footnote 2

Notes

Fleet News, November 2015, p.12.

The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW), 1978, as amended.

References

AfDB. (2011) Eastern Africa Regional Integration Strategy Paper 2011–2015. Côte d'Ivoire: African Development Bank Group, http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/East%20Africa%20-%20Rev%20RISP%20.pdf.

AfDB, OECD, UNDP. (2015) African Economic Outlook: Regional Development and Spatial Inclusion. OECD Publishing: Paris.

Ashburner L (1994) Women in management careers: opportunities and outcomes. In: Evetts J (ed). Women & Career: Themes and Issues in Advanced Industrial Societies. Longman Group UK Ltd: London.

Belcher P, Sampson H, Thomas M, Veiga J and Zhao M (2003) Women Seafarers: Global Employment Policies and Practices. ILO: Geneva, Switzerland.

BIMCO and ICS. (2016) Manpower Report: The Global Supply and Demand for Seafarers in 2015. Maritime International Secretariat Services Limited: London.

Bostock J (2014) The Meaning of Success: Insights from Women at Cambridge. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Brenton P, Gamberoni E and Sear C (eds) (2013) Women and Trade in Africa: Realizing the Potential. World Bank: Washington DC.

COMESA. (2014) Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA): Annual Report 2014. COMESA: Lusaka, Zambia.

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature; 50 (4): 1051–1079.

Dunson DB, Colombo B and Baird DD (2002) Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Journal of Human Reproduction; 17 (5): 1399–1403.

Enke KAE and Ropers-Huilman R (2010) Defining and achieving success: perspectives from students at Catholic women’s colleges. Higher Education in Review; 7, 1–22, Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/admin_pubs.

EU. (n.d.) Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA), http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/esa/. accessed on 1 March 2016.

Grant C, Grant V (2015) Women in the maritime sector: Surviving and thriving in a man’s world—A caribbean perspective. In: Kitada M, Williams E and Froholdt LL (eds). Maritime Women: Global Leadership. Springer: Heidelberg, Germany.

Greed C (1994) Women surveyors: constructing careers. In: Evetts J (ed). Women & Career: Themes and Issues in Advanced Industrial Societies. Longman: London.

ILO. (2011) Work–Life Balance; The 312th Session, GB.312/POL/4 ILO: Geneva, Switzerland.

ILO. (2013) Women in the Transport Sector: Transport Policy Brief 2013. ILO: Geneva, Switzerland.

ILO. (2015) Women in Business and Management: Gaining Momentum. ILO: Geneva, Switzerland.

Han J, Kamber M and Pei J (2012) Data Mining Concepts and Techniques, 3rd Edition, Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: Waltham, MA.

Holdaway S and Parker SK (1998) Policing women police: Uniform patrol, promotion and representation in the CID. British Journal of Criminology; 38 (1): 40–60.

Kalet AL, Fletcher KE, Ferdman DJ and Bickell NA (2006) Defining, navigating, and negotiating success: The experiences of mid-career Robert Wood Johnson clinical scholar women. Journal of General Internal Medicine; 21, 920–925, http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00524.x.

Kitada M (2010) Women Seafarers and their Identities. PhD thesis. Cardiff University.

Kitada M (2011) Rethinking the occupational culture of seafaring: challenges in the new era of cultural diversities. Ocean Law, Society and Management; 3, 80–97.

Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM, Guest G and Namey E (2005) Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. Family Health International: Research Triangle Park, NC.

Mackenzie B (2015) The “leaky pipeline”: Examining and addressing the loss of women at consecutive career stages in marine engineering, science and technology. In: Kitada M, Williams E and Froholdt LL (eds). Maritime Women: Global Leadership. Springer: Heidelberg, Germany.

Maynard M (1994) Methods, practice and epistemology: The debate about feminism and research. In: Maynard M and Purvis J (eds). Researching Women’s Lives from a Feminist Perspective. Taylor and Francis: London.

McGinn KL, Castro MR and Lingo EL (2015) Mums the Word! Cross-national Relationship between Maternal Employment and Gender Inequalities at Work and at Home. Harvard Business School: Brighton, UK.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2015) The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality can add $12 Trillion to Global Growth. McKinsey and Company: London.

Moustakas C (1994) Phenomenological Research Methods. Sage: London.

OECD. (2012) Poverty Reduction and Pro-Poor Growth: The Role of Empowerment. OECD Publishing: Paris, France.

OECD. (2015) How’s Life? 2015: Measuring Well-being. OECD Publishing: Paris, France.

Orsel K (2015) Women in shipping: Navigating to the top. In: Kitada M, Williams E and Froholdt LL (eds). Maritime Women: Global Leadership. Springer: Heidelberg, Germany.

Pastra AS, Koufopoulos DN, Gkliatis IP (2015) Board characteristics and the presence of women on the board of directors: The case of the greek shipping sector. In: Kitada M, Williams E and Froholdt LL (eds). Maritime Women: Global Leadership. Springer: Heidelberg, Germany.

Pettersson L et al. (2008) Changing gender relations: Women officers’ experiences in the Swedish armed forces. Economic and Industrial Democracy; 29 (2): 192–216.

Rule P and John VM (2015) A necessary dialogue: Theory in case study research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods; 14 (4): 1–11.

Tansey P (2015) Women at the Helm: 25 Years of IMO’s gender programme. In: Kitada M, Williams E and Froholdt LL (eds). Maritime Women: Global Leadership. Springer: Heidelberg, Germany.

Yoder JD and Aniakudo P (1996) When pranks become harassment: The case of African American women firefighters. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research; 35 (5-6): 253–270.

Vitz P (1999) Family Decline: The Findings of Social Science. Catholic Education Research Centre: Powell River, BC.

World Bank. (2011) The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Getting to Equal: Promoting Gender Equality through Human Development. World Bank Group: Washington DC.

World Economic Forum. (2015) The Global Gender Gap Report 2015. World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deep appreciation to the WOMESA for their generous support to conduct research on women in the regions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bhirugnath-Bhookhun, M., Kitada, M. Lost in success: women’s maritime careers in Eastern and Southern Africa. Palgrave Commun 3, 17023 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.23