Abstract

The aim of this article is to understand women’s intellectual activities involving Shakespeare’s playbooks by analysing their various book-related activities, such as annotating, editing, signing and attaching ex libris to books. Although researchers have increasingly recognized women’s participation in the canonization of Shakespeare, ex libris and book users’ signatures, unlike other resources, have not been systematically studied in relation to gender. Discreet observations and evaluations, typified by reading, are rarely appreciated as a participatory or creative process. However, it is hoped that this study focusing on women’s use of Shakespeare’s playbooks will give a voice to these seemingly quiet interpreters. For primary sources, more than 800 pre-1769 copies of Shakespeare’s playbooks held in major libraries throughout the world, including the British Library and Folger Shakespeare Library, were consulted. This research shows that women were actively involved in book-related activities; for example, they exchanged Shakespeare’s playbooks as gifts and preserved rare copies as family treasures. Some female readers even annotated Shakespeare’s works earlier than believed, approximately 40 years before the publication of Harriet Bowdler’s The Family Shakespeare in 1807. This article is published as part of a collection to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Discreet observations and evaluations, typified by reading, are rarely appreciated as participatory and creative processes, but sometimes these seemingly silent interpreters can be given a voice by looking at a certain type of document: the books they used. Women who read or watched William Shakespeare’s plays have recently attracted attention, and the contributions by famous women, such as Margaret Cavendish, Aphra Behn and the Shakespeare Ladies Club, have gradually gained notice. It is more difficult, though, to understand how quiet, lesser-known female interpreters received Shakespeare’s works in the early modern period. By looking at these women’s various book-related activities, including annotating, editing, signing and attaching ex libris, this article attempts to understand what kind of women used Shakespeare’s books and how they received his works from the seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century. On the basis of large-scale research and analysis of more than 850 copies of pre-mid-eighteenth-century Shakespeare editions housed in 12 major libraries in North America, Europe and Japan, this article describes and analyses the small marks left by women on the playbooks and demonstrates that these previously unknown women actively engaged in book-related activities concerning Shakespeare. This research reveals the history of women’s reception of Shakespeare and their participation in Shakespeare studies at an early stage of the canonization of his works.

The ex libris and signatures in Shakespeare playbooks and poems are informative historical resources for researchers seeking to catch a glimpse of individual users’ interpretations of and attachment to these books.Footnote 1 Unlike other resources, these books have not been systematically studied from the perspective of gender, although women’s participation in the canonization of the playwright and the annotations found in early modern books are both increasingly well recognized.2 For example, Roberts (2003: 169) has analysed copies owned by the Folger Shakespeare Library (hereafter, the Folger) in detail, including the signatures and annotations left by women in the library’s 1640 copy of Poems (STC 22344 Copy 10, Appendix 6–41)Footnote 2 but the holdings of other major libraries have not yet been thoroughly examined. Smith’s (2016: 176–182) recent work elaborated on the female readers of the First Folio but did not extend to other early editions. The ownership histories of the Second, Third and Fourth Folios and the quartos have been far less frequently studied than the First Folio.4 This article, therefore, focuses on copies of the less commonly studied editions associated with women, as well as libraries not analysed by other researchers. The seemingly trivial and sporadic marks of ownership found in these copies illustrate how these female book users made their own personal volumes of Shakespeare and used them to share a cultural legacy with their relatives and friends in the reading community.

This article consists of four sections. The first section “Research Overview” provides an overview of research on the playbooks of Shakespeare. The second section “Seventeenth-century women and Shakespeare’s Playbooks” investigates seventeenth-century women’s use of Shakespeare’s playbooks, while the third section “Eighteenth-Century Women and Shakespeare as a Cultural Legacy” discusses several interesting early copies of Shakespeare that highlight female users’ personal relationships with their own volumes and their changing attitudes towards Shakespeare during the eighteenth century. The final section “Women Studying Shakespeare” treats women’s increasingly active involvement in Shakespeare scholarship in the eighteenth century.

Research overview

Before a discussion of individual copies, this section explains the research method and summarizes the results of the investigations. In this project, a survey of women’s ex libris and signatures in copies of Shakespeare’s playbooks published before 1769 was conducted. The year 1769 was chosen as the cut-off point as the Shakespeare Jubilee held in Stratford-upon-Avon that year marked the climax of bardolatry (Dobson, 1992: 134–85). In this research, all the copies of Shakespeare’s playbooks (and, in some cases, his poems, anthologies and adaptations) published before 1769 held at the British Library, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Meisei University Shakespeare Folio Collection (hereafter, the Meisei Collection), Senate House Library of the University of London and University of Glasgow Library were examined to determine whether they were associated with women. The copies with identifiable ex libris or signatures featuring women’s names were counted, excluding those marks made by bookbinders, librarians and current library patrons, such as Emily Jordan Folger, co-founder of the Folger, and participants in the British Library’s Adopt a Book project. The estimation presented in this article is conservative as it does not include cropped and mostly invisible marks. Copies with possible associations with female users held by major libraries, such as the Folger, Huntington Library, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, New York Public Library, Morgan Library, Auckland City Library and Bodleian Library, were also consulted.

This article focuses on ex libris and signatures and only analyses particularly notable annotations in detail. Playbooks rarely feature both ownership marks and annotations. If a copy does have both, the annotations were not always written by the user indicated by the ownership mark as old books usually have been used by many people. Scholars have already analysed the few rare copies where the signer is highly likely to also be the annotator.

Only a small number of ownership marks, regardless of the user’s gender, can be found, and it is even more difficult to find books clearly used by women. For example, the British Library’s catalogue lists at least 532 pre-1769 copies of works associated with Shakespeare, but this number is not definite, and the library is believed to own more volumes for three key reasons. First, the catalogues do not associate some adaptations with Shakespeare’s name, and these are not returned in the results for catalogue searches. Second, some volumes, especially quarto volumes bound together with many other quartos and disbanded volumes, are not catalogued correctly. Third, the publication dates are sometimes uncertain, especially for made-up copies and those without dates and title pages. It was possible to check 509 copies, some of which are available online.Footnote 3 The other 23 volumes were not retrievable as they were not available online and could not be accessed as they were either fragile or being exhibited at the time. Of the 509 copies, only 32 (6.5%) are associated with approximately 21 female names, including famous collector Frances Wolfreston (C.34.k.64., Appendix 1–119). Many of these copies are associated with unidentified users. In general, female users rarely attached ex libris or identifiable signatures to their copies.

The copies associated with women tend to have multiple ownership marks. They were used by more than one woman, exchanged or inherited as book users in early modern Europe often presented volumes to relatives and friends as gifts. According to Davis (1983: 82), who focused on gift-giving in sixteenth-century France, early modern intellectuals especially appreciated books as gifts as they were durable and appropriate for any person of any gender or class in any season. Brown (2010: 32) describes how male and female writers exchanged their works “in a system of reciprocal favour or gift exchange”. The ownership marks found in Shakespeare’s playbooks testify to the frequent gift-giving among general users of books. This investigation revealed that at least 11 of these copies were given and received among multiple identified women, while at least 12 copies were passed between identified men and women during the seventeenth to the late-eighteenth century (Appendices 1–6). Many users exchanged books without regard to the gender of either the giver or the recipient.

Seventeenth-century women and Shakespeare’s playbooks

Most of the volumes possibly used by women before 1700 are either copies associated with unidentified users (see Appendices 1–6) or feature only simple signatures with no notes, providing minimal information about the users’ social status or place of residence. It, therefore, is almost impossible to know the users’ personal views of the playbooks. Nevertheless, the social backgrounds of the identified female users and their relationships with the books are relatively diverse.

Several copies are associated with seventeenth-century female users who have already been identified and are well known among scholars, such as Frances Wolfreston (C.34.k.64., Appendix 1–119 and STC 22278 Copy 2, Appendix 6–25) and Lucy Hutchinson’s daughter Elizabeth Hutchinson (STC 22273 Fo.1 no.54, Appendix 6–20).6 Several other examples have identifiable owners but are less well known. This article introduces for the first time six examples that provide significant information about female users of Shakespeare’s playbooks during this period, comparing previously unidentified users to the already identified women. These examples expand knowledge of the different classes of female readers of Shakespeare and offer evidence of the diverse material uses of books.

Among the copies of Shakespeare’s playbooks used by women in Renaissance London, a copy of the Second Folio held at the Folger (Fo.2 no.03, Appendix 6–26) is especially interesting as its ownership mark was written by a book merchant, Sarah Jones. The copy contains a note written in a seventeenth-century hand: “Sold the 14th of February 1649; this booke, and I warrant it to be of the best addition, and perfectt; booke; sold by me SI Sarah Iones hir marke widdow at the whit hors book seller in the littl Britton, in london;” (πA1r). Unfortunately, this is a made-up copy in a bad condition, and according to the Hamnet catalogue, several pages in this copy including this leaf were taken from another unknown copy of the Second Folio, and perhaps it is not the copy of the Second Folio that was owned by Jones herself, although she had at least one copy which included this leaf. Jones was a registered stationer whose husband, William Jones, worked as a stationer from 1589 to 1618. After his death, she inherited his business and “Assigned ouer vnto” John Wright her rights to The Schoole of Good Manners and Mucedorus (Arber, 1894: iii. 632). Although little else is known about Jones, she had been in business for approximately thirty years when she wrote this note and perhaps was an experienced book merchant who could evaluate the condition of books and sell them with warranties.Footnote 4 Her use of the word “perfect” implies her experience in the book trade for it was often used to refer to the condition of books by seventeenth-century merchants: in 1611, the Stationers’ Company promised to deliver “one perfect Booke of euery such Booke (in quiers)” to Oxford University (Stationers’ Company, 1611), and book merchant Richard Chiswell also used the term in his advertisements.8 During the English Renaissance, it was not unusual for a widow to become a printer after the death of her husband, and some such women actively engaged in the business (Smith, 2012: 90–91). For example, Alice Warren, the widow of printer Thomas Warren, Eleanor (also known as Ellen) Cotes, widow of Richard Cotes, and Mary Allott, widow of Robert Allott, were all involved to some extent in printing Shakespeare editions in Renaissance London.Footnote 5 Jones’ business-related note then is an early example of widows’ economic activities in the book industry.

Unsurprisingly, multiple pieces of evidence attest that aristocratic women of wealth and education could own and use copies of Shakespeare’s playbooks. Here, consider three examples, one already discussed in previous studies and two newly found. First, Sasha Roberts has found that the copy of the Second Folio (STC 22274 Fo.2 no.22, Appendix 6–30) possessed by Elizabeth of Bohemia was also owned by her son Prince Rupert and at least four aristocratic women close to the queen, which is the best example illustrating the use of books as gifts (2003: 49). Elizabeth of Bohemia was the nominal patron of Lady Elizabeth’s Men in England and organized so many theatrical performances at her court in exile at The Hague that she “irritated the strict Dutch Calvinists” (Asch, 2016). Of 20 plays performed at her wedding celebration in 1613, at least seven were Shakespeare’s (Chambers, 1930: ii. 343). Second, a copy of the Second Folio held at the Folger (Fo.2 no.31, Appendix 6–31) is signed by “Judith Killigrew” (πA2r), identified by the library catalogue as a woman who died in 1683. She was the mother of poet and painter Anne Killigrew, and her husband Henry was the brother of two dramatists, William and Thomas Killigrew.10 Judith was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Catharine of Braganza and a skilled lute, guitar and theorbo player (Huygens, 1882: 57 and Westrup (1941–42): 51). Third, a sammelband volume held by the British Library (841.d.39, Appendix 1–153~154), which includes Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet from 1695 and Nahum Tate’s The History of King Lear from 1681, was perhaps owned by Lady Elizabeth Ashley, the wife of James Harris and daughter of Anthony Ashley Cooper, second Earl of Shaftesbury (Hicks, 1995: 8). The front flyleaf of the volume is inscribed “Lady Elizabeth Ashley 1700” and on the same leaf are written two lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 2.Footnote 6 Lady Ashley’s son James Harris was a scholar and Shakespeare enthusiast. His friends and family members, including his daughters Gertrude and Louisa, staged amateur productions of several plays, including The Sheep-Shearing: Or, Florizel and Perdita and Macnamara Morgan’s 1754 adaptation of The Winter’s Tale, between 1770 and 1782 in Salisbury (Dobson, 2011: 38). These records concerning book users demonstrate that Shakespeare’s works were known among aristocratic women. All three female users had some connection with the theatrical culture of the period and might have obtained Shakespeare’s playbooks partly as they already had knowledge of drama as elite women with active artistic interests.

Three copies used by women in the Restoration period testify to the wider circulation of Shakespeare’s playbooks. First is a copy of the Third Folio held in the Meisei Collection (MR1571, Appendix 3–50), which was purchased by a Cornish woman. On its first flyleaf is pasted a handwritten label which reads “Elisabeth Gregor her Book 1689 this I bought at second hand price”. In this period, the indication of the user’s name with the phrase “his/her book” was often found in handwritten notes and printed book labels pasted on books (Lee, 1976: xii). The same leaf features the nineteenth-century printed ex libris of G. W. F. Gregor signed by “Elizabeth H” (A2r). The woman who wrote this note was Elizabeth Moyle Gregor, the wife of John Gregor and mother of Francis Gregor, whose family lived in Trewarthenick, Cornwall, and owned a large library of books dating from the 1680 s. Elizabeth Moyle Gregor selected and annotated many books in the collection, although most are now missing (North, 1996: 13). She also owned at least one manuscript of poems written in English and Latin and signed it as “Elisabeth Moyle” on the first flyleaf in 1684.12 Elizabeth and John married on 8 July 1684 (Jewers, 1889: 70), and sometime between 1684 and 1689, she changed her signature from Moyle to Gregor. Following in the footsteps of Elizabeth Moyle Gregor, her granddaughter Elizabeth Gregor also engaged book collecting, making her own book label (Lee, 1979: 140n220). Elizabeth Moyle Gregor’s mention of a “second hand price” implies that she was a diligent library manager who paid great attention to cost when purchasing books. This example shows that nonaristocratic women living in rural areas could also build large libraries during this time. After the English Civil War, the influence of the English language and popular culture dominated in Cornwall (Ellis, 1974: 78–80). Gregor’s library, which included Shakespeare’s playbooks, hints at the expanding influence of English drama in areas both geographically and culturally different from London.

A copy of the Fourth Folio held by the Folger (Fo.4 no.19, Appendix 6–48) was owned by an Irishwoman and her female relatives. It features three women’s names written in seventeenth-century hand: “Frances Lovett widow her Booke” (front-flyleaf), “Rebeckah Ashe her Book given her by Frances Lovett” (back flyleaf) and “Mary Lovett” (back flyleaf). As the library catalogue suggests, the Lovett family of Liscombe originally owned this copy. “Frances Lovett widow” is Frances O’Moore Lovett, the wife of Christopher Lovett, lord mayor of Dublin, who used the name “Frances Lovett, widow” from her husband’s death in approximately 1680 until her death in 1715.Footnote 7 She was the daughter of Pierce O’Moore of Raheen and distantly related to the poet Thomas Moore (Lovett, 1941: 56). More importantly, she was related to the famous rebel Chief Rory O’Moore, and she was “much ronged” by society, to borrow her daughter-in-law Mary’s phrase (Verney, 1930: ii. 196–97). Among the several Lovett women named “Mary”, the signer “Mary Lovett” likely was the daughter of Sir John Verney, first Viscount Fermanagh, who married John Lovett, the son of Frances and Christopher. Mary Lovett was a playgoer in Dublin and, judging from the Lovetts’ letters, was on good terms with her mother-in-law.14 Two women stand as possible candidates for “Rebeckah Ashe”. Mary and John’s son Robert Lovett married his cousin Rebecca Ashe and lived with her in Dromoyle and Tipperary. Mary and John’s other son Christopher had a daughter named Rebecca, who married a man from the Ashe family. The Lovett family had abundant opportunities to obtain books from England as Frances Lovett’s husband Christopher was a successful fabric merchant who travelled as far as Turkey. This copy seems to have been bound in calf around the early modern period, which suggests that the Lovetts were a wealthy family interested in keeping books in an orderly manner. The copy might have been heavily used as its binding is loose. In addition to the intellectual activities of wealthy, prosperous, privileged Dublin merchants, the ownership history of the Lovett family’s Fourth Folio indicates English influence on Irish culture as an Irish woman married an Englishman and the future lord mayor of Dublin, obtained a copy of Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio and passed it down to her daughter-in-law from England.

A sammelband volume from the British Library’s collection (841.c.3., Appendix 1-178-187) provides information about the user’s personal relationship with her books. This volume contains Julius Caesar from 1691, Macbeth (Davenant’s adaptation) from 1695, Othello from 1705, The History of King Lear (Tate’s adaptation) from 1702, Henry IV (Thomas Betterton’s adaptation) from 1700, Troilus and Cressida, or Truth Found Too Late (Dryden’s adaptation) from 1671, The Tempest, or the Enchanted Island (Shadwell’s adaptation) from 1671, The Jew of Venice (Granville’s adaptation) from 1701, the libretto of Purcell’s operatic adaptation The Fairy Queen from 1692 and Hamlet from 1703. The front flyleaf of Julius Caesar is signed “Eliz. Dolben 1691” and features the book label that belonged to Eliza Dolben, also known as Elizabeth Raynsford, the wife of John Nicholls Raynsford of Brixworth, Northamptonshire. Printed book labels, relatively simple indicators of the owners’ names, were commonly used in England around the sixteenth century and became popular after 1730 (Lee, 1979: 16; Rickards and Twyman, 2000: 57). More modest than sumptuous armorial bookplates, they were preferred by yeomen, “ladies” and men of letters (Lee, 1976: xiii). Although Dolben was not an aristocrat, her book label can be located within this trend. Between 1735 and 1743, she etched book labels for herself, her brother William and her second cousin’s Cornish husband Robert Trefusis (Blatchly, 2004). Compared with other book labels in this period, Dolben’s three handmade labels, with flourishes encircling calligraphic representations of the names, are “very unusual” (Lee, 1979: 146). If Blatchly’s analyses are correct, Dolben was a creative amateur etcher, relatively rare among women in this period.Footnote 8

Plaque A.12-1965 at the Victoria and Albert Museum states that Eliza Raynsford died in 1810 at age 88 years, which would make her born in around 1722 or some 31 years after the date of the signature on the playbook. The owner of the book label, Eliza Dolben (hereafter, the younger Elizabeth), then is not the Eliz Dolben who signed the front leaf and was active in 1691. The signer, instead, is her great-aunt Elizabeth Dolben (hereafter, the elder Elizabeth), the daughter of Tanfield Mulso of Finedon, Northamptonshire, who married John Dolben sometime before 1686 and died in 1736.16 The younger Elizabeth inherited the copy upon the death of the elder Elizabeth and later attached her own book label to the volume. The younger Elizabeth likely was a book lover from girlhood as she created her own book label. Pasted on the same flyleaf that her grandaunt signed, the younger Elizabeth’s book label suggests that women in this period made their own volumes of Shakespeare. While the volume was treated as a cultural inheritance from her grand-aunt, it also became her personal volume.

These examples hint at two realities in the seventeenth century. First, during this period, nonaristocratic women living in areas geographically distant from London had opportunities to obtain and use Shakespeare’s playbooks and participated in reading culture as actively as the elite women in London. Second, these female book users tended to consider Shakespeare playbooks to be legacies given and received among family members. This attitude is also found in the eighteenth century, as discussed in the next section.

Eighteenth-century women and Shakespeare as a cultural legacy

As alluded in the preceding section, early editions of Shakespeare’s playbooks were regarded as cultural inheritance within families. This tendency became more conspicuous in the eighteenth century, as can be seen in the eight examples discussed here. Many copies of Shakespeare’s books are associated with unidentified eighteenth-century women, but information could be found only for some users.

Although unique, a copy of the Fourth Folio (Fo.4 no.12, Appendix 6–46) has received much less scholarly attention than the First Folio. Sarah Burnes, a female user of this book, repeatedly inscribed her name in this copy—“Sarah Burnes Her Book” (πA1r, πA2r, A1r, *3B5r) and “Sarah Burnes” (πA4r and 3F5v)—in the same eighteenth-century hand. Unfortunately, her name was too common to identify the individual behind it. She was obviously interested in Shakespeare as she wrote out the four-line epitaph from his gravestone (πA3v). She was also an active reader who cared about her library for she boasted: “I could have had ten pound for this Book, but would not take it. S. Burnes” (πA4r). This statement implies that eighteenth-century readers regarded the book trade as a prosperous market. Perhaps Burnes saw other readers acquire money by selling used books or book merchants sell expensive old copies. She, though, refused to sell her copy in one of the proudest declarations of eighteenth-century female readers’ abiding love for Shakespeare’s playbooks. Readers rarely inscribed such a strong desire for preservation. Burnes was a very active reader who not only took pleasure in reading Shakespeare’s plays but also in knowing about his background (such as his epitaph) and attempted to preserve his early editions as a precious cultural heritage.

Yet more evidence reveals another active female reader of Shakespeare, although she was not as proud as Burnes. A copy of the Second Folio held by the Folger (Fo.2 no.57, Appendix 6–36) contains comments made by an otherwise unknown female reader. The copy is inscribed “Mary Elmer her book given by Mr Thorold” (2i5v) and “John Thorold” (3a6v) in an eighteenth-century hand. “John Thorold” and “Mr Thorold” belong to the Thorold family who owned a large library, including a copy of the First Folio now at the Folger (Fo.1 no.07). The identity of Mary Elmer is unclear, although the note indicates that she knew members of the Thorold family. Elmer wrote in the Second Folio “See what joy tis to heare of his wifes death” regarding Anthony’s response to Fulvia’s death (2y5v) and “Mary Elmer this loue is a strang[e] thing” beside Cleopatra’s line “But let it be, I am quickly ill, and well,/So Anthony loves” (2y6r).Footnote 9 These comments suggest Elmer’s surprise at the passionate, inconstant nature of the love between Antony and Cleopatra in the play but are too short to understand her views in detail. The comical tone of the comments also expresses her relaxed attitude towards reading.

Some copies show that women close to each other exchanged playbooks. A copy of the Third Folio in the Meisei Collection (MR4354, Appendix 3–62) was used by women in the house of Baron Bergavenny in the eighteenth century, as evidenced by a handwritten note on its bookplate: “Nevillia Thomas The Gift of her Dear Mother Charlotte Senior”. The latter is identified as Charlotte Senior (née Walter), the heiress of Baron Bergavenny, who was born in 1736, married Ascanius William Senior in 1768 and died in 1811. “Nevillia Thomas” is her daughter Nevillia, who was born in 1769, married William Thomas of Winkfield in 1792 and died in 1842 (Foster, 1883: 15–16). The bookplate implies that this copy served as a token of remembrance of a fond mother–daughter relationship. Another volume hinting at the kinship ties of female book users is a copy of the Fourth Folio at the Folger (Fo.4 no.18, Appendix 6–47) signed by many women: “Elizabeth Grey” in a nineteenth-century hand (Y6r), “Anne Grey Anna Grey” (2G3r) and “the Gift of Constantia Grey to her daughter Anne Grey of Shoston May 19th 1766” (3O5r). It belonged to the Greys (sometimes spelled Grays) of Shoreston, a prosperous family in eighteenth-century Northumberland, but the signers are not individually identifiable as their names were common in this family (Burke, 1833–38: ii. 329).

The Thomas-Senior Third Folio at Meisei contains an interesting note on its second flyleaf: “In affectionate remembrance of the attachment and esteem of a departed friend; This Volume is presented to Sir T. D. Acland Bart; as a sincere, tho” inadequate expressions, of the deep sense of gratitude and respect, entertained for him by her surviving Relations. January 1843’. This note suggests that, after Nevillia Thomas died, her relatives sent the copy to her friend Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, tenth Baronet (Courtney and Matthew, 2004). As well, the Thomas-Senior Third Folio seems to have not been regarded as such an expensive, rare book as we consider it today as it was a “sincere, tho” inadequate’ gift for the close friend. Adding to the evidence that women often inherited books from their female relatives, the history of this copy shows that friends of both sexes, not only relatives, shared remembrances of deceased women.

Cousins of different sexes also enjoyed sending and receiving books. A Welsh family owned a copy of the sixth volume of the 1747 edition of Hanmer’s The Works of Shakespear (PR2752 1747c2 copy 3 v. 6 Sh.Col., Appendix 6–67). Its front flyleaf is inscribed “The gift of Watkin Wynne Esqr., to Anna Maria Griffiths, 1748”. Watkin was a common male name among the Wynnes of Wales during the eighteenth century, but this Watkin Wynne might have been the son of Cadwaladr Wynne, the husband of Jane Griffith, while Anna Maria Griffith likely was the daughter of Jane’s brother John Griffith (Burke, 1841: 1093–94; Glen, 1934: 128). Watkin Wynne and Anna Maria Griffith appear to have been on good terms and exchanged gifts, including Shakespeare’s works, although Cadwaladr Wynne and John Griffith had legal conflicts in the late seventeenth century (National Library of Wales, 1956: 30). Like the copy given by Elmer to Thorold, this volume shows that relatives and friends of different sexes exchanged playbooks as gifts.

Another copy of Hanmer’s Shakespeare (PR2752 1747c2 copy 2 Sh.Col, Appendix 6–66), whose female owner has already been identified, was also exchanged as a gift between a woman and her male cousin. The list of the owners is behind the title leaf of the first volume, perhaps written by a later owner: “Ashley Cowper 1748, Lady Hesketh 1751, Willm. Cowper 1797, John Handy 1802” (A1v). Ashley Cowper passed on this copy to his daughter Lady Harriet Hesketh, who was born in 1733 and died in 1807 (Kelly, 2008). However, she was still Harriet Cowper when she received the book from her father in 1751 as she did not marry Thomas Hesketh until around 1754. She presented it to her favourite cousin, well-known writer William Cowper, who might have kept it until his death in 1800 (Baird, 2013). Mary Cowper, a member of the Shakespeare Ladies Club, was another cousin of Harriet Hesketh (Dobson, 1992: 148–53). Harriet Hesketh was well known in social circles, mingling with literary figures such as Frances Burney and Cowper. Burney states that Hesketh “appeared to much advantage, with respect to conversation, abilities, and good breeding” (Burney, 1904: i. 445). Shakespeare was a familiar name to her as she jokingly compares her cousin John Johnson to the playwright in a letter dated 10 July 1798: “if he inclines to hear his own heavenly lines immediately, you will doubtless let Shakespeare wait” (Hesketh, 1901: 64). This statement shows that Shakespeare had already achieved canonical status among the educated in late eighteenth-century England.

Older women sometimes left their books to younger male relatives. A copy of the Fourth Folio at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Res YK32) is associated with the name of a woman from the latter half of the eighteenth century and suggests a kinship tie. A handwritten note on the front flyleaf declares: “Lewis Barton Buckle given by Mrs. Catherine Barton Widow of Prior’s Court”. According to the National Archives’ catalogue record for the Buckle Papers at the West Sussex Record Office, this Lewis Barton Buckle, who was born in 1786 and died in 1819, was the son of Lewis Buckle and his wife Frances Bachelor, the daughter of Thomas Bachelor of Prior Court House, Berkshire. The exact identity of Mrs. Catherine Barton is unclear, although it seems certain that she was an older female relative. She might have belonged to the Barton family living in Prior Court House and passed her copy onto Lewis Barton Buckle as a gift. The endpaper of the 1737 copy of Hamlet (PR2807 1737 copy 1 Sh.Col., Appendix 6–62) is inscribed “Elibris Eliza. Tollet, 1737” and “Charles Tollet”. The female signer is the poet Elizabeth Tollet, who was born in 1694 and died in 1754 (Londry, 2008a). A highly educated woman, she was fluent in multiple languages and acquainted with many prominent intellectuals, including Isaac Newton. Before signing this copy, she anonymously published Poems on Several Occasions in 1724, and other of her poems were also circulated in manuscript form. Charles Tollet was her nephew, the younger brother of George Tollet (Londry, 2008b), a Shakespearean scholar who contributed to Samuel Johnson and George Steevens’ edition (Sherbo, 1981). The two brothers inherited most of their aunt’s books, and George Tollet benefited from Elizabeth Tollet’s copies of Shakespeare. Like Elizabeth Brockett’s Second Folio inherited by her nephew William Brockett (Fo.1 no.23, Appendix 6–11), as described in detail by many scholars, the aunt gave the book to her (perhaps favourite) nephew.18 These copies are yet more evidence supporting the frequent use of playbooks as gifts among relatives.

These traces left behind by female users show how friends and relatives used Shakespeare’s books to strengthen their bonds. Among the eight copies discussed, six were exchanged between women and men, including cousins. This pattern implies that, in this period, book users commonly gave and received books with relatives and friends of different sexes. Each copy was an individual material object that carried emotional value as a gift, which might be difficult for twenty-first-century readers to understand. Furthermore, as evident in Burnes’ note, intellectually active female readers began to emerge during this period. The final section of this article discusses these highly motivated women’s book-related activities concerning Shakespeare.

Women studying Shakespeare

More informative clues about the deepening relationship between female users and Shakespeare’s playbooks in the widening landscape that existed for readers in the eighteenth century can be dug up. Some female book users began studying Shakespeare, reading not only the play texts but also relevant critical works and recording their intellectual activities in annotations. Three women stand as good examples of female contributors to research on Shakespeare during the eighteenth century.

Clara Reeve, a Gothic novelist who was born in 1729 and died in 1807 (Kelly, 2010), used a copy of the Second Folio (Fo.2 no.13, Appendix 6–27). Its front flyleaf contains a long handwritten note dated 1773 and her father William’s signature (Z6r), whom Reeve, in her note, commends him as “a great admirer of Shakespeare”. She records that “[t]his Book has been in the Reeve family about one hundred years” and that her grandfather Thomas Reeve, who “set a very high Value upon it”, initially obtained it. After William’s death in 1755, her aunt Maria owned this copy and then presented it to Reeve. She blames those who borrowed the copy from Maria for having “abused” it and asserts the importance of preserving the family copy, declaring “I hope it will never go out of the family”. Reeve also mentions Johnson’s and Steevens’ scholarly works when discussing the publication history of Shakespeare’s Folios. While she relates the pleasure of using the books to familial bonds, her reception of Shakespeare is connected to a wider public discussion after Johnson and Steevens’ publication of academic studies of Shakespeare. Her note vividly indicates her desire for cultural heritage: she maintains her family’s private heritage through understanding and preserving Shakespeare’s works but also refers to scholarly discourses on Shakespeare and invokes a wider reading community to emphasize the value of her family’s copy. This intersection of private pleasure and public appreciation of Shakespeare indicates the progression of the canonization of Shakespeare during the eighteenth century. At this time, critical analyses of Shakespeare were widely circulated in various publications, ranging from multivolume works to short magazine reviews. Through reading such discourses, users could develop their personal pleasures derived from reading into more complex critical standards shared by larger reading communities. This copy shows that Reeve actively engaged in this process as an intellectual writer.

The work of Mary Lever (sometimes spelled Leaver) is another notable case. The copy of the Third Folio owned by the Auckland City Library (hereafter, the Auckland Third Folio) indicates that she helped her husband, Rev. Thomas Hawkins, edit the second edition of Thomas Hanmer’s The Works of Shakespear, which was supervised by Hawkins and published from 1770 to 1771.Footnote 10 The Auckland Third Folio contains Hawkins’s bookplate and is thoroughly collated with the First and Second Folios in preparation to update Hanmer’s work. According to Lever’s descendants, she, not her husband Thomas, wrote most of these scholarly marginal notes concerning the differences between the editions. This copy includes a transcript of a letter written by the Reverend W. Edward Lush, Lever’s great-grandson, to his nephew A. Lush on 31 January 1948: “At the date of writing this the third folio copy is on loan at the Auckland Public library. I do not praise their methods of keeping books; it is to be yours; it has, as you know, handwriting marginal notes of Mary Lever’s handwriting. We always call her Mary Lever: she was the wife of Rev. Thomas Hawkins, my Mother’s Grandmother”. This note conveys the author’s complaint about the conservation of the copy, as does Reeve’s comment. Lever and Hawkins owned the Auckland Third Folio and passed it on to their granddaughter Blanche. She married Rev. Vicesimus Lush in England in 1842, and the couple immigrated to Auckland in 1850, bringing their books with them.20

Lever’s intellectual activities as preserved in the Auckland Third Folio show that women had already begun editing Shakespeare approximately 40 years before the publication of Henrietta Maria (called Harriet) Bowdler’s The Family Shakespeare in 1807. Although Bowdler was largely responsible for editing the volume, her brother Thomas was credited as the editor to maintain her honour, and she was acknowledged as the principal editor only in the 1960s (Perrin, 1992: 63). Both Bowdler and Lever have remained obscure in the history of Shakespeare studies, suggesting that male kinsmen’s work has often overshadowed women’s scholarly activities.

The Auckland Third Folio also indicates the emotional and cultural value of Shakespeare playbooks as family memorials and a cultural tradition of the British Empire. The books that Hawkins and Lever used to proofread Hanmer’s edition include the Folger-owned Theobald’s The Works of Shakespeare (PR2752 1752 copy 1 Sh. Col.), Bodleian Library’s Second Folio (Percy 90/Arch. G c.15) and British Library’s Fourth Folio (C.39.k.17., Appendix 1–166). The copy of the First Folio they used has not been identified. The Folger’s The Works of Shakespeare, with Hawkins’ bookplates in the third and seventh volumes remaining in good condition, apparently was a copy for daily use. Hawkins signed the front flyleaf of the first volume on 10 June 1756, about 10 years before he married, and thoroughly annotated all the volumes. He gave the Second Folio to his friend Thomas Percy, bishop of Dromore.Footnote 11 This copy is also thoroughly annotated, and the library note states that Hawkins himself annotated it. The annotation styles suggest that this is highly likely. Two short letters from Hawkins to Percy, dated 12 January 1770 and 23 February 1770, are attached to the end of this copy. According to the notes in the front flyleaves, the Fourth Folio at the British Library was “collated by Mr T. Hawkins, (editor of the second Edition of Hanmers’ Shakespeare 1771,) with the two first folio editions, in 1623, and 1632”.22

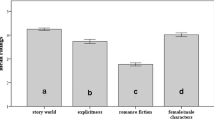

Among the Folio editions used by Hawkins and Lever, the First Folio was lost, the Second Folio was held by Percy, and the Fourth Folio was presented to Warton (see Fig. 1). Only the Auckland Third Folio, the copy featuring Mary’s annotations, remained in the hands of the Hawkins and Lushes as a family heirloom, suggesting that the family retained it as a relic of Hawkins and Lever’s editorial efforts. Their descendants in New Zealand considered it a memorial to their great-grandmother’s intellectual abilities and her contributions to English literary culture.

Shakespeare’s Playbooks used by the Hawkins. They used at least five editions of Shakespeare. The First Folio was lost, the Second Folio was held by Percy, the Fourth Folio was presented to Warton, and the Auckland Third Folio remained in the hands of the Hawkins and Lushes. The Folger owns Thomas Hawkins’ copy of The Works of Shakespeare.

Another piece of evidence shows women’s activities in the editing community. Five of the Pavier quartos housed at the Folger are associated with Miss Orlebar, an eighteenth-century woman who was a friend and helper of male collectors, including Percy. The front flyleaf of the 1619 copy of The Whole Contention Betweene the Two Famous Houses, Lancaster and Yorke (STC 26101 copy 2, Appendix 6–7) features a note handwritten by Percy dated May 8 1763: “Miss Orlebars made me a present of this book with a view that I shd. give it to my friend Mr Garmer, who was collecting Quarto Editions of Shakespeare plays”. Miss Orlebars belonged to the Orlebar family living in Hinwick Hall, Bedfordshire, in the eighteenth century (Burke, 1833–38: i. 246). Percy knew John Orlebar’s children well, and this “Miss Orlebars” must be one of his daughters: Mary (1730–1821), Elizabeth (1732–1810) and Constantia (1739–1808) (Davis, 1989: 151–52). The library catalogue states that Miss Orlebar also owned and sent to Percy the 1619 copies of Henry V (STC 22291 Copy 7, Appendix 6–3), The Merchant of Venice (STC 22297 Copy 4, Appendix 6–4), The Merry Wives of Windsor (STC 22300 Copy 7, Appendix 6–5), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (STC 22303 Copy 6, Appendix 6–6) and Sir John Oldcastle, a play misattributed to Shakespeare (STC 18796 Copy 3). The female Orlebars were educated women with an active interest in literary matters and left behind many private writings, including letters and Mary’s poems.Footnote 12 In addition to Lever’s annotations, the Orlebar records hint that female users of the books contributed to Shakespeare studies in their infancy.

These three examples demonstrate female users’ desires to preserve Shakespeare’s plays as national heritage and family inheritance. Reeve’s Second Folio reveals her desire to preserve the book as her family heritage in a private, domestic community and the text as a national heritage. For the Lushes in New Zealand, Hawkins’ Third Folio signified English culture and their ancestors’ contributions to it. The Orlebars’ copies indicate women’s hidden contributions to Shakespeare studies. These copies show that eighteenth-century female intellectuals were involved in the development of early Shakespeare studies and the preservation of his works during their popularization and canonization.

Conclusion

Although seemingly trivial, the ownership marks left in early editions of Shakespeare demonstrate that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century women actively made their own volumes of Shakespeare. These women’s private interactions with these books, including signing and annotating them, however, are not as personal as they might seem. Privately owned volumes could be shared by many people through gift-giving, inheritance and scholarly activities. We, as researchers in reading rooms, find ourselves at a new point in the long history of book sharing. As evident from the copies belonging to Reeve and Lever, books can carry a family’s cultural memories and commemorate the intellectual activities of larger communities, such as nations and academia. These women’s efforts to create their own volumes of Shakespeare allow us to catch a glimpse of their intellectual relationships with the author.

Data availability

Details of the appendix material cited in this paper are listed in full in a spreadsheet deposited in the Harvard Dataverse (Kitamura, 2017: doi:10.7910/DVN/DB3OXQ).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sae K (2017) A Shakespeare of one’s own: female users of playbooks from the seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century. Palgrave Communications. 3:17021 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.21. Footnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23

Notes

In this paper, the term ex libris refers to various kinds of ownership marks printed or written on paper and pasted on books. Bookplate refers to a plate bearing “a decorative or pictorial motif expressive of the book’s owner” (Rickards and Twyman, 2000: 61), and book label to “the owner’s name label” (Rickards and Twyman, 2000: 58), although these words are sometimes used interchangeably (Lee, 1976: x). Ex libris is often used to refer to all these ownership marks (Rickards and Twyman, 2000: 61).

Details of the appendix material cited in this paper are listed in full in a spreadsheet deposited in the Harvard Dataverse (Kitamura, 2017: doi:10.7910/DVN/DB3OXQ).

Five copies of the First Folio are described in detail in Rasmussen and West’s catalogue, although none is associated with women (2012: 47–66).

Her name was not found in the ESTC or listed in “Women printers, publishers and booksellers” by Smith and Cardinale (1990: 313–14).

Concerning these women’s involvement in publishing, see Dawson (1946: 21), Dugas (2006: 93), Farr (1934: 131–33), Finkelstein (2000: 316–36), King (2008: 47) and Spencer (1958: 246).

The British Library has another copy of a sammelband volume (841.c.6., Appendix 1–155~156) signed “Elizabeth Ashley Feby the 27th 1705”. This copy includes Charles Gildon’s Measure for Measure, or, Beauty the Best Advocate from 1700 and George Granville’s The Jew of Venice from 1701. This book might have been owned by the same woman.

One of Christopher and Frances’ daughters was also named Frances, but she was not the signer. She was usually called “Fanny” (Mary Lovett’s letter to Lady Fermanagh on 8 September 1703, Verney, 1930: i. 195) and changed her surname after marrying Sir John Vanbrugh’s cousin Edward Pearce. After the death of her husband, she was called “Mrs. Pearce, the widow” (William Butterfield’s letter to Lord Fermanagh on 19 May 1736, Verney, 1930: ii. 106).

On women etchers and engravers in eighteenth-century Britain and Europe in general, see Gaze (1997: i. 61–65) and O’Day (2008: 329).

Mayer briefly describes this copy, although he cannot identify the signer (2012: 42). This paper follows his transcription rather than that found in Hamnet.

This edition has attracted little scholarly attention. Sherbo (1986) conducted one of the few substantial studies on it but does not mention Lever. Woudhuysen (2013), although informative, mostly covers nineteenth-century female editors.

This copy is briefly described by Hanson (1951: 85) and registered as manuscript PeT 680 by Beal (1980: ii. 335).

Documents related to the Orlebars are listed in ‘Sources for women’s history’ by Bedfordshire and Luton Archives and Records Service. For Mary Orlebar’s poems, see Collett-White (1993).

For example, Ritchie (2014) provided a helpful work on women’s dramatic activities and involvement with Shakespeare’s work in the eighteenth century, while Sherman (2008) gave a detailed description of both male and female readers’ annotations in early modern England.

West (2003) published a census of the First Folio, which was updated by Rasmussen and West (2012). No worldwide quarto census has been conducted since 1939 (Bartlett and Pollard, 1939). The Second, Third and Fourth Folios have not been the subject of a major census, except for one of the copies held by American institutions as of 1990 (Otness, 1990).

Roberts described in detail the copies owned by Elizabeth, queen of Bohemia, (STC 22274 Fo.2 no.22, Appendix 6–30) and the Hutchinson family (STC 22273 Fo.1 no.54, Appendix 6–20) (2003: 48, 58).

In 1690, Richard Chiswell issued an advertisement of Thomas Pope Blount’s Censura attached to a copy of Burnet’s (1690: 36) A Sermon Preached before the Queen, queen, promising to distribute “One perfect Book in Sheets”. Chiswell also offered the ‘Delivery of a Perfect Book in Quires’ in an advertisement in another book published in 1699 (Fairfax 1699).

On the Killigrew’s family history, see Andreadis (2001: 111–23), Hopkins (2004) and Motten (2008).

This manuscript is registered as Perdita in Beinecke Library MS pb 110 and described by Burke (2008: 147–48).

Mary and her family “went to the Play” on the queen’s birthday (Mary Lovett’s letter to Lady Fermanagh on 26 March 1707, Verney, 1930: i. 200). Mary states that Frances was “mightily kind and fond of me” (Mary Lovett’s letter to Lord Fermanagh on 15 November 1703, Verney, 1930: i. 196), and Frances wrote to Lord Fermanagh on 2 August 1708 to tell him that she was happy to welcome Mary’s sister Elizabeth Verney to her home in Ireland (Verney, 1930: i. 206).

Elizabeth Raynsford’s father John Dolben was the son of Gilbert Dolben, and his brother John Dolben married Tanfield Mulso’s daughter Eliz Dolben, the signer of the book. According to Courtney and Baker (2004), they married in the West Indies in 1686. If this assumption is correct, then it would have been relatively difficult for Eliz Dolben to obtain the copy. The transcript of John’s brother Gilbert’s letter, though, suggests that the couple lived in Britain until around 1691 (Cruickshanks et al., 2002: iii. 896). If the date estimation in the letter is accurate, she would have been able to more easily acquire the copy.

The Broketts’ copy is known to researchers as Elizabeth Brockett copied a poem by Lady Mary Chudleigh entitled ‘To the Ladies’ in it. It is described in detail by Hodgdon (2010: 49n1), Kastan (2003: 180) and Roberts (1995: 303).

For the Lush family history, see Lush (1971).

This copy is briefly described by Tillotson (1944: 23n30).

References

Andreadis H (2001) Sappho in Early Modern England: Female Same-Sex Literary Erotics, 1550–1714. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL.

Arber E (ed) (1894) A Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers of London, 1554–1640A.D, vol 5, London.

Asch RG (2016) Elizabeth, Princess (1596–1662). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8638.

Baird JD (2013) Cowper, William (1731–1800). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6513.

Bartlett HC and Pollard AW (1939) A Census of Shakespeare’s Plays in Quarto, 1594–1709, Rev. edn., Yale University Press: New Haven, CT.

Beal P (1980) Index of English Literary Manuscripts: 1450–1625. vol 2, Mansell: London.

Blatchly J (2004) The Afflecks and the Dolbens. The Bookplate Journal; 2nd Series 2 (1): 64–65.

Brown CC (2010) Losing and regaining the material meanings of epistolary and gift texts. In: Daybell J and Peter Hinds (eds). Material Readings of Early Modern Culture: Texts and Social Practices, 1580–1730. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK 47–64.

Burke J (1833–38) A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, vol 4, London.

Burke J (1841) A Genealogy and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. London.

Burke VE (2008) Women’s verse miscellany manuscripts in the perdita project: Examples and generalizations. In: Denbo M (ed) New Ways of Looking at Old Texts, IV: Papers of the Renaissance English Text Society 2002–2006. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies: Tempe, AZ, pp 141–154.

Burney F (1904) Diary and Letters of Madame D’arblay (1778–1840). In: Barrett C (ed). vol 6, Palgrave Macmillan: New York.

Burnet G (1690) A Sermon Preached before the Queen. Chiswell: London.

Chambers EK (1930) William Shakespeare. vol 2, Clarendon Press: Oxford.

Collett-White J (1993) My choice: A poem written in 1751 by Mary Orlebar. Bedfordshire Historical Miscellany: Essays in Honour of Patricia Bell; 72, 129–41.

Courtney WP and Baker AP (2004) Dolben, John (bap. 1662, d. 1710). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7776.

Courtney WP and Matthew HCG (2004) Acland, Sir Thomas Dyke, tenth baronet (1787–1871). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/66.

Cruickshanks E, Hayton DW and Handley S (eds) (2002) The House of Commons, 1690–1715, Vol. 3: Members A-F. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Davis BH (1989) Thomas Percy: A Scholar-Cleric in the Age of Johnson. University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA.

Davis NZ (1983) Beyond the market: Books as gifts in Sixteenth-century France. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society; 33, 69–88.

Dawson GE (1946) The copyright of Shakespeare’s Dramatic works. Studies in Honor of A. H. R. Fairchild: The University of Missouri Studies; 21 (1): 9–36.

Dobson M (1992) The Making of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660–1769. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

Dobson M (2011) Shakespeare and Amateur Performance: A Cultural History. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Dugas D (2006) Marketing the Bard: Shakespeare in Performance and Print 1660–1740. University of Missouri Press: Columbia, MS.

Ellis PB (1974) The Cornish Language and Its Literature. Routledge: London.

Fairfax T (1699) Short Memorials of Thomas Lord Fairfax Written by Himself. Chiswell: London.

Farr H (1934) Philip Chetwind and the Allott Copyrights. The Library; 4th series 15 (2): 129–60.

Finkelstein R (2000) The Politics of Gender, Puritanism, and Shakespeare’s Third Folio. Philological Quarterly; 79 (3): 315–341.

Foster J (1883) The Royal Lineage of Our Noble and Gentle Families, Together with Their Parental Ancestry. Hazell, Watson, and Viney: London.

Gaze D (ed) (1997) Dictionary of Women Artists. vol. 2, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers: London.

Glenn TA (1934) The Family of Griffith of Garn and Plasnewydd in the County of Denbigh. Harrison and Sons: London.

Hanson LW (1951) The Shakespeare collection in the Bodleian Library. Shakespeare Survey: Oxford, pp 78–96.

Hesketh H (1901) Letters of Lady Hesketh to the Rev. John Johnson, LL.D. In: Johnson CB (ed). Jarrold and Sons: London.

Hicks P (1995) Further comments on two performances of Nathum Tate’s King Lear in 1701, their dates and cast. Theatre Notebook; 49 (1): 3–11.

Hodgdon B (2010) (ed) The Taming of the Shrew. The Arden Shakespeare 3rd Series William Shakespeare. Methuen: London.

Hopkins D (2004) Killigrew, Anne (1660–1685). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15530.

Huygens C (1882) Correspondance et Œuvre Musicales de Constantin Huygens. In: Jonckoloet WJA and Land JPN (eds). Brill: Leyde, the Netherlands.

Jewers AJ (1889) Heraldic Church Notes from Cornwall. Mitchell and Hughes: London.

Kastan DS (2003) Performances and Playbooks: The Closing of the Theatres and the Politics of Drama. In: Sharpe KM and Zwicker SN (eds). Reading, Society and Politics in Early Modern England. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, pp 167–84.

Kelly G (2010) Reeve, Clara (1729–1807). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23292.

Kelly JW (2008) Hesketh, Harriet, Lady Hesketh (bap. 1733, d. 1807). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13124.

King EGC (2008) In the Character of Shakespeare: Canon, Authorship, and Attribution in Eighteenth-century England. Unpublished doctoral thesis. The University of Auckland.

Kitamura S (2017) Supplementary Information for 'A Shakespeare of One’s Own: Female Users of Playbooks from the Seventeenth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century'. Harvard Dataverse. doi:10.7910/DVN/DB3OXQ.

Lee BN (1976) Early Printed Book Labels: A Catalogue of Dates Personal Labels and Gift Labels Printed in Britain to the Year 1760. Private Libraries Association: Pinner, UK.

Lee BN (1979) British Bookplates: A Pictorial History. David and Charles: Newton Abbot, UK.

Londry M (2008a) Tollet, Elizabeth (1694–1754). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27502.

Londry M (2008b) Tollet, George (bap. 1725, d. 1779). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27503.

Lovett EN (1941) Mr Lovett out of Ireland. Dublin Historical Record; 3 (54–66): 79–80.

Lush V (1971) Drummond A (ed) The Auckland Journals of Vicesimus Lush, 1850–63. Pegasus: Christchurch, New Zealand.

Mayer J (2012) Rewriting Shakespeare: Shakespeare’s Early modern readers at work. Études Épistémè; 21, 1–47. doi:10.4000/episteme.400.

Motten JPV (2008) Killigrew, Henry (1613–1700). ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15534.

National Library of Wales. (1956) Annual Report 1955–1956. The National Library of Wales: Aberystwyth, Wales.

North C (1996) Trewarthenick, Cornwall. The Historian; 50, 13–15.

O’Day R (2008) Family Galleries: Women and Art in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Huntington Library Quarterly; 71 (2): 323–49.

Otness HM (1990) The Shakespeare Folio Handbook and Census. Greenwood: New York.

Perrin N (1992) Dr Bowdler’s Legacy: A History of Expurgated Books in England and America, 3rd edn., Godine: Boston, MA.

Rasmussen E and West AJ (eds) (2012) The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK.

Rickards M and Twyman M (eds) (2000) The Encyclopedia of Ephemera: A Guide to the Fragmentary Documents of Everyday Life for the Collector, Curator, and Historian. Routledge: New York.

Ritchie FJ (2014) Women and Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Roberts S (1995) Reading the Shakespearean text in early modern England. Critical Survey; 7 (3): 299–306.

Roberts S (2003) Reading Shakespeare’s Poems in Early Modern England. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK.

Sherbo A (1981) The library of George tollet, neglected Shakespearean. Studies in Bibliography; 34, 227–238.

Sherbo A (1986) The Birth of Shakespeare Studies: Commentators from Rowe (1709) to Boswell-Malone (1821). Colleagues Press: East Lansing, MI.

Sherman WH (2008) Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England. University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA.

Smith E (2016) Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Smith H (2012) ‘Grossly Material Things’: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Smith H and Cardinale S (eds) (1990) Women and the Literature of the Seventeenth Century: An Annotated Bibliography based on Wing’s Short-title Catalogue. Greenwood: London.

Spencer L (1958) The printing of Sir George Croke’s reports. Studies in Bibliography; 11, 231–246.

Stationers’ Company (1611) Vicesimo Octavo Ianuarij 1611. Nono Regni Regis Iacobi Present, the Master, Wardens, and Assistants of the Company of Stationers. London.

Tillotson A (ed) (1944) The Percy Letters: The Correspondence of Thomas Percy and Edmond Malone. Thomas Percy and Edmond Malone. Louisiana State University Press: New Orleans, LA.

Verney MM (ed) (1930) The Verney Letters of the Eighteenth Century: From the Manuscripts at Claydon House. vol 2, Ernest Benn: London.

West AJ (2003) The Shakespeare First Folio: The History of the Book. vol 2, Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Westrup JA (1941–42) Domestic music under the Stuarts. Proceedings of the Musical Association; 68, 19–53.

Woudhuysen HR (2013) Some women editors of Shakespeare: A Preliminary Sketch. In: McMullan G, Orlin LC and Mason V (eds). Women Making Shakespeare: Text, Reception and Performance. Arden Shakespeare: London, pp 79–88.

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this paper is funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26884055, the Yoshida Scholarship Foundation, and Musashi University Soken Project. This paper is partly based on the presentation of the same title given on 1 April 2015 at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America, the other presentation titled “Readers to the Sea: Immigrant Books, Shakespeare, and Women in the British Empire” given on 15 June 2012 at the BritGrad Shakespeare 2012, and my PhD thesis “The Role of Women in the Canonisation of Shakespeare: From Elizabethan Theatre to the Shakespeare Jubilee” (unpublished PhD thesis, King’s College London, 2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sae, K. A Shakespeare of one’s own: female users of playbooks from the seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century. Palgrave Commun 3, 17021 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.21