Abstract

Objectives:

We aim to validate the effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) on fat distribution and glucose metabolism in Han Chinese populations.

Methods:

We genotyped six tag single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of GIP and four tag SNPs of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) among 2884 community-based individuals from Han Chinese populations. Linear analysis was applied to test the associations of these variants with visceral fat area (VFA) and subcutaneous fat area (SFA) quantified by magnetic resonance imaging as well as glucose-related traits.

Results:

We found that the C allele of rs4794008 of GIP tended to increase the VFA and the VFA/SFA ratio in all subjects (P=0.050 and P=0.054, respectively), and rs4794008 was associated with the VFA/SFA ratio in males (P=0.041) after adjusting for the BMI. The VFA-increasing allele of rs4794008 was not related to any glucose metabolism traits. However, rs9904288 of GIP was associated with the SFA in males as well as glucose-related traits in all subjects (P range, 0.004–0.049), and the GIPR variants displayed associations with both fat- and glucose-related traits.

Conclusions:

The results could provide the evidence that GIP might modulate visceral fat accumulation via incretin function or independent of incretin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is currently one of the most common and severe complex disorders worldwide. It causes a great economic burden on public health not only due to the large number of individuals with obesity, but also the associated consequences.1 Visceral fat accumulation is the culprit in a variety of obesity-related disorders, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases.2 Effective management and intervention for obesity, especially for visceral adiposity, should be implemented to decrease the prevalence of T2DM and other metabolic diseases.

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) is an important amino-acid peptide hormone that is secreted from the gut and then binds to glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptors (GIPRs) after a meal. Given that GIPRs are expressed in various tissues, including pancreatic islets, adipocytes, brain and stomach, GIP signaling has been implicated in various activities, which may link overnutrition to obesity, insulin resistance and T2DM. Rodent studies have demonstrated the interference in the stimulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion as well as the modulation of beta-cell neogenesis, differentiation and proliferation (the so-called intrapancreatic actions).3, 4, 5 GIP also has additional extrapancreatic actions in addition to facilitating insulin release. The vitro studies on direct adipocyte actions showed GIP could enhance the lipoprotein lipase enzyme activity in cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes.6 The blockade of GIPR signaling by GIPR knockout mice or GIP antagonist could decrease fat deposition under overnutrition.7, 8, 9 In support of this, increasing genetic evidence has demonstrated that GIPR variants were associated with plasma glucose levels,10 an index of incretin effect derived from an oral glucose tolerance test and an intravenous glucose tolerance test11 as well as with BMI12, 13 among European and East Asian populations, indicating that GIP signaling may participate in glucose metabolism and obesity. Nonetheless, the GIP variants directly linked to obesity or insulin dysfunction are less well characterized. Moreover, a recent study by Moller et al.14 indicated an association of the GIP level with low density lipoprotein and increased visceral fat area (VFA) independent of insulin action, suggesting the role of GIP in modulating adiposity deposits. Only one study from Japan showed that GIP variants might contribute to visceral fat accumulation as well as plasma triglyceride and hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c) levels irrespective of BMI.15

To increase our understanding of the contributions of the GIP–GIPR axis, our study aims to examine the effects of GIP and GIPR variants on fat distribution and metabolic traits among 2884 community-based individuals of Han Chinese ancestry.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Our study was approved by the institution review board of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration II. A total of 2884 community-based Han Chinese individuals were enrolled. Individuals with cancers, severe mental disorders and disabilities were excluded, and the remaining subjects provided written informed consent. The subjects received anthropometric measurements, magnetic resonance imaging assessment and laboratory examinations.

Clinical phenotypes

Anthropometric measurements included height, weight and waist circumference (WC) and hip circumferences. The BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2), and the waist-to-hip ratio was calculated as the WC (cm)/hip circumference (cm) ratio. Body fat percentage (%) was assessed with a TBF-410 Tanita Body Composition Analyzer (Tanita, Tokyo, Japan). An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging scan was performed on each subject at the umbilicus level between L4 and L5 in the supine position (Archive, Philips Medical System, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). To calculate VFA (cm2) and subcutaneous fat area (SFA (cm2)), two trained observers assessed the images with SLICE-O-MATIC image analysis software (version 4.2; Tom Vision Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada). If the results differed by more than 10%, a third observer who was blinded to the results reanalyzed the images. Venous blood samples were drawn at 0, 30 and 120 min following glucose solution ingestion to assess glucose and insulin concentrations. Glucose levels were assayed using the glucose oxidase method, and insulin levels were measured using a radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, St Charles, MO, USA). We calculated the areas under the curve for glucose and insulin (GAUC and IAUC) using the trapezoidal rule and estimated the insulinogenic index (change in insulin level/change in glucose level from 0 to 30 min). Insulin sensitivity and secretion were estimated according to the computations proposed by Stumvoll et al. and Gutt et al.,16, 17 and three indices were generated (Stumvoll first phase and second phase insulin secretion and the Gutt index).

Tag SNP selection and genotyping

According to Nakayama et al.,15 six tag single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of GIP located between 30 kb upstream and 30 kb downstream of the GIP region were selected based on the HapMap Phase III JPT+CHB database using a threshold of r2⩾0.8. We also selected four tag SNPs for GIPR that were located between 8 kb upstream and 24 kb downstream of the GIPR gene. These SNPs tag 100% of common SNPs with a minor allele frequency of >0.05. All of the SNPs were genotyped with a MassARRAY Compact Analyzer (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA). All of the SNPs passed quality control with call rates >95% and concordant rates >99%.

Statistical analysis

The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was applied before analysis. Pairwise linkage disequilibrium analyses were performed using Haploview (version 4.2; www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/haploview/). The skewed distribution traits were log10-transformed. Linear regression analysis was used to test for the effects of SNPs on quantitative traits under the additive genetic model using PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/). The analyses were adjusted for covariates, such as age, sex and other variables, if appropriate. Logistic regression was used to confirm the best model of PLINK epistatic analyses. A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Power calculations were performed by Quanto software (http://biostats.usc.edu/Quanto.html, version 1.2.4, May 2009) with current sample size. We had 71.6% power to detect an association for a SNP (minor allele frequency=0.46) accounting for 2.8 cm2 of the variation in VFA and 46.9% power to detect an association for this SNP accounting for 3.3 cm2 of the variation in SFA at the 0.05 significance.

Results

Association with obesity-related traits

All of the variants conformed to the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P>0.05). The pairwise linkage disequilibrium maps of GIP and GIPR variants are shown in Supplementary Figure 1, and the subject characteristics are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 2, we observed that SNPs in GIP exhibited only borderline associations with fat distribution indices, including VFA, SFA and the VFA/SFA ratio. Specifically, rs11650936 was associated with the VFA/SFA ratio before adjusting for BMI (P=0.048), whereas the C allele of rs4794008 also tended to be associated with an increased VFA and VFA/SFA ratio after adjusting for BMI (P=0.050 and P=0.054, respectively). In contrast, minor associations between rs11671664 in GIPR were observed for VFA and SFA before adjusting for BMI (P=0.018 and P=0.020, respectively). The previously reported GIPR SNP rs11671664 was related to BMI and WC as expected, whereas rs12941604 of GIP showed a slight association with WC (P range, 0.0043–0.0184).

Because of the heterogeneity in adiposity function and adipose deposits between males and females, we also performed a subgroup analysis stratified by gender (shown in Table 3). rs4794008 of GIP was associated with the VFA/SFA ratio without or with adjustment of the BMI in male subjects (P=0.040 and P=0.041, respectively). The other two SNPs, rs9904288 and rs2291725, of GIP were associated with SFA after adjustment of the BMI in males (P=0.004 and P=0.029, respectively). Regarding the GIPR SNPs, rs11671664 was associated with VFA before BMI adjustment in males (P=0.030). In contrast, only rs11671664 of GIPR showed a slight association with SFA in female subjects (P=0.049). However, we failed to identify any gender interaction of these variants for distribution traits.

Association with glucose metabolism traits

In terms of glucose-related traits, rs9904288 of GIP was the most significant SNP among GIP variants and was associated with a range of glucose metabolism traits (shown in Table 4). The SFA-increasing allele rs9904288 was associated with decreased 2 h glucose and 2 h insulin levels and an elevated insulinogenic index and insulin sensitivity (assessed with the Gutt index) (P range, 0.014–0.049), whereas the rs4794008 SNP of GIP showed a nominal association with VFA in males and no association with glucose-related traits. Compared to the tag SNPs of GIP, rs2287019 and rs11671664 of GIPR were associated with the glucose and insulin levels, the insulinogenic index and the Gutt index (P range, 9.46 × 10−5–0.028).

Gene–gene epistasis

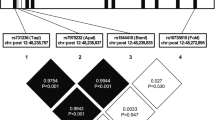

To avoid overlooking the heritability of obesity traits due to unknown interactions between GIP and GIPR variants, we performed gene–gene interaction (epistasis) analyses. The results showed that rs4794008 of GIP and rs2287019 of GIPR exhibited significant epistatic effects on SFA in all subjects and in female subjects using the genotypic model (P=0.0313 and P=0.0178, respectively) (Figure 1).

Discussion

We investigated the association of six tag SNPs of GIP and four tag SNPs of GIPR with fat distribution and glucose-related traits in 2884 Han Chinese individuals. rs4794008 of GIP was associated with visceral fat accumulation, whereas other GIP and GIPR variants (that is, rs9904288 of GIP, rs11671664 and rs2287019 of GIPR) were related to both fat distribution and glucose-related traits. Moreover, we found that rs4794008 of GIP and rs2287019 of GIPR exhibited significant epistatic effects on subcutaneous fat accumulation. Consistent with the physiological and pathological functions of the GIP–GIPR axis on intrapancreatic and extrapancreatic activity, our findings indicated that GIP variants could regulate visceral adiposity via two possible paths that were either mediated by incretin effects or independent of incretin effects.

Similar to previous genome-wide association study (GWAS) analyses between European and East Asian populations,12, 13, 18 we observed that rs11671664 and 2287019 of GIPR were associated with BMI and glucose-related traits. Nakayama et al.15 found that rs9904288 of GIP was related to visceral fat accumulation, but rs4794008 only displayed an association with the HBA1c level in Japanese populations, which we did not replicate in this study. Although the sample sizes were comparable, the heterogeneity between the two studies was expected based on the use of the bioelectrical impedance method in the Japanese study and magnetic resonance imaging scans in our study to assess visceral fat and subcutaneous fat accumulation. Moreover, to determine whether these associations with GIP variants reflected differences between overall obesity and fat distribution, we repeated our association analysis, including BMI, as a covariate. Studies that directly investigate the associations of GIP and GIPR variants with fat distribution and related metabolic traits independent of BMI must be conducted. Harada et al.19 identified that a splice GIPR variant expressed in mouse pancreatic cells affected GIPR sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Whether the variants of GIPR tested in our study impact the sensitivity of GIPR in human body needs to be investigated in further study.

A series of studies provided evidence supporting the role of GIP in regulating obesity. In vitro studies on direct adipocyte action indicated that GIP stimulates adipocyte lipoprotein lipase activity, which is responsible for the hydrolysis of triglycerides in circulating blood and for promoting lipogenesis by increasing free fatty acid uptake by adipocytes.6, 20 The effects of GIP on animal and human adipose storage and metabolism are mixed. Mice maintained on a high-fat diet exhibited increased GIP mRNA expression, GIP secretion and K-cell density, and inhibition of GIP action by GIPR ablation or antagonists reversed high-fat-induced obesity and improved insulin sensitivity7, 9, 21 Nonetheless, some other studies showed that GIPR−/− mice exhibited similar adiposity with wild-type mice on normal diet7 and specific GIPR knockout mice in adiposity did not reduce fat volume but decreased liver weight and insulin resistance.22 GIP in combination with hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia increased triacylglycerol deposition in subcutaneous fat by enhancing free fatty acid re-esterification in lean human subjects.23 However, in obese patients, GIP did not induce changes in triacylglycerol uptake in adipose tissue during hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemic clamping,24 potentially due to disrupted GIP signaling in insulin-resistant and excess weight states. A recent study pointed out that GIP infusion was able to stimulate insulin secretion in the lean, obesity or obesity patients with impaired glucose regulation (IGR) rather than obesity patients with T2DM, whereas resulted in the anabolic effect (that means exaggerated fat deposit) in obesity patients with T2DM, indicating the blunted insulinotropic but preserved lipogenic actions in obesity patients with T2DM.25 To date, it is difficult to dissect the separate contributions of insulin and GIP to glucose and lipid metabolism. We primarily identified GIP variants that likely regulate visceral adiposity via two possible paths: mediated by incretin or independent of incretin effects. The pattern by which genetic variants interact as well as the modifying role of insulin appears different between normal individuals and individuals with obesity, which can be informative about biological function in further.

The concept of epistasis originally referred to an allelic effect at one locus being concealed by the effect of another allele at a second locus. However, a more recent definition has been extended to include the effect of an allele at a genetic variant that depends either on the presence or absence of another genetic variant.26 Considering the biological crosstalk between GIP and GIPR, we searched for epistatic effects. Interestingly, although rs4794008 of GIP and rs2287019 of GIPR were not associated with SFA per se, they exhibited statistically significant epistatic effects on subcutaneous fat accumulation in all subjects and in female subjects. The discovery and replication of functional epistasis are warranted in the interpretation of genetic association studies.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevented us from investigating the effect of GIP variants on the natural history of visceral fat accumulation. Second, all of the variants tested in our study were in non-coding regions, and the potential relationship between GIP levels, fat distribution and related metabolic traits should be investigated in future studies. Moreover, false positives should not be excluded due to the modest effect of GIP variants on fat distribution traits and the difficulty of performing multiple corrections. Nonetheless, our findings provide novel information based on previous functional evidence implying that the possible paths by which GIP variants modulate visceral fat accumulation can be incretin dependent or independent. Thus, it is imperative to replicate the effect of GIP variants on visceral fat accumulation and related metabolic traits.

Conclusions

In summary, we observed that GIP rs4794008 was associated with visceral fat accumulation, and other GIP and GIPR variants were related to both fat distribution and glucose-related traits in 2884 Han Chinese individuals, implying that GIP variants regulate visceral adiposity via incretin-dependent and -independent effects. Further functional studies are needed to confirm and elucidate the underlying mechanism and the characteristics of treatment responses to become a potential target for obesity.

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 766–781.

Patel P, Abate N . Body fat distribution and insulin resistance. Nutrients 2013; 5: 2019–2027.

Cho YM, Kieffer TJ . K-cells and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in health and disease. Vitam Horm 2010; 84: 111–150.

Seino Y, Fukushima M, Yabe D . GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: similarities and differences. J Diabetes Investig 2010; 1: 8–23.

Renner S, Fehlings C, Herbach N, Hofmann A, von Waldthausen DC, Kessler B et al. Glucose intolerance and reduced proliferation of pancreatic beta-cells in transgenic pigs with impaired glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide function. Diabetes 2010; 59: 1228–1238.

Kim SJ, Nian C, McIntosh CH . Activation of lipoprotein lipase by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in adipocytes. A role for a protein kinase B, LKB1, and AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 8557–8567.

Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Ban N, Ihara Y, Tsukiyama K, Zhou H et al. Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nat Med 2002; 8: 738–742.

McClean PL, Irwin N, Cassidy RS, Holst JJ, Gault VA, Flatt PR . GIP receptor antagonism reverses obesity, insulin resistance, and associated metabolic disturbances induced in mice by prolonged consumption of high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007; 293: E1746–E1755.

Irwin N, Flatt PR . Therapeutic potential for GIP receptor agonists and antagonists. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 23: 499–512.

Sauber J, Grothe J, Behm M, Scherag A, Grallert H, Illig T et al. Association of variants in gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor gene with impaired glucose homeostasis in obese children and adolescents from Berlin. Eur J Endocrinol 2010; 163: 259–264.

Saxena R, Hivert MF, Langenberg C, Tanaka T, Pankow JS, Vollenweider P et al. Genetic variation in GIPR influences the glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 142–148.

Okada Y, Kubo M, Ohmiya H, Takahashi A, Kumasaka N, Hosono N et al. Common variants at CDKAL1 and KLF9 are associated with body mass index in east Asian populations. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 302–306.

Wen W, Cho YS, Zheng W, Dorajoo R, Kato N, Qi L et al. Meta-analysis identifies common variants associated with body mass index in east Asians. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 307–311.

Moller CL, Vistisen D, Faerch K, Johansen NB, Witte DR, Jonsson A et al. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Is Associated With Lower Low-Density Lipoprotein But Unhealthy Fat Distribution, Independent of Insulin: The ADDITION-PRO Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101: 485–493.

Nakayama K, Watanabe K, Boonvisut S, Makishima S, Miyashita H, Iwamoto S . Common variants of GIP are associated with visceral fat accumulation in Japanese adults. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014; 307: G1108–G1114.

Stumvoll M, Van Haeften T, Fritsche A, Gerich J . Oral glucose tolerance test indexes for insulin sensitivity and secretion based on various availabilities of sampling times. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 796–797.

Gutt M, Davis CL, Spitzer SB, Llabre MM, Kumar M, Czarnecki EM et al. Validation of the insulin sensitivity index (ISI(0,120)): comparison with other measures. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2000; 47: 177–184.

Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 937–948.

Harada N, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, Yamada C, Nakamura Y, Mukai E et al. A novel GIP receptor splice variant influences GIP sensitivity of pancreatic beta-cells in obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294: E61–E68.

Kim SJ, Nian C, McIntosh CH . Resistin is a key mediator of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) stimulation of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity in adipocytes. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 34139–34147.

Althage MC, Ford EL, Wang S, Tso P, Polonsky KS, Wice BM . Targeted ablation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide-producing cells in transgenic mice reduces obesity and insulin resistance induced by a high fat diet. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 18365–18376.

Joo E, Harada N, Yamane S, Fukushima T, Taura D, Iwasaki K et al. Inhibition of Gastric Inhibitory Polypeptide Receptor Signaling in Adipose Tissue Reduces Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Steatosis in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Diabetes 2017; 66: 868–879.

Asmar M, Simonsen L, Madsbad S, Stallknecht B, Holst JJ, Bulow J . Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide may enhance fatty acid re-esterification in subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue in lean humans. Diabetes 2010; 59: 2160–2163.

Asmar M, Simonsen L, Arngrim N, Holst JJ, Dela F, Bulow J . Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide has impaired effect on abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue metabolism in obese subjects. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 259–265.

Thondam SK, Daousi C, Wilding JP, Holst JJ, Ameen GI, Yang C et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide promotes lipid deposition in subcutaneous adipocytes in obese, type 2 diabetes patients: a maladaptive response. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2017; 312: E224–E233.

Niel C, Sinoquet C, Dina C, Rocheleau G . A survey about methods dedicated to epistasis detection. Front Genet 2015; 6: 285.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2016YFA0502003), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants (81322010, 81570713 and 81300691), the Shanghai Jiaotong Medical/Engineering Foundation (YG2014MS18), the National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals, Shanghai Municipal Education Commission – Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20152527), the Innovation Fund for PhD Students from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (BXJ201633) and the Innovation Foundation of Translational Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and Shanghai SJTUSM Biobank (15ZH4006). We thank all of the research volunteers and cooperative workers for their participation. We thank the support from Dr Takuya Mori and Dr Akira Shimotoyodome from the Biological Science Laboratories, Kao Corporation, for the conception of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Nutrition & Diabetes website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Ma, X., Tang, T. et al. The effect of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) variants on visceral fat accumulation in Han Chinese populations. Nutr. Diabetes 7, e278 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2017.28

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2017.28