Abstract

Increased newborn adiposity is associated with later adverse metabolic outcomes. Previous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) demonstrated strong association of a locus on chromosome 3 (3q25.31) with newborn sum of skinfolds, a measure of overall adiposity. Whether this locus is associated with childhood adiposity is unknown. Genotype and sum of skinfolds data were available for 293 children at birth and age 2, and for 350 children at birth and age 6 from a European cohort (Belfast, UK) who participated in the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome GWAS. We examined single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at the 3q25.31 locus associated with newborn adiposity. Linear regression analyses under an additive genetic model adjusting for maternal body mass index were performed. In both cohorts, a positive association was observed between all SNPs and sum of skinfolds at birth (P=2.3 × 10−4, β=0.026 and P=4.8 × 10−4, β=0.025). At the age of 2 years, a non-significant negative association was observed with sum of skinfolds (P=0.06; β =−0.015). At the age of 6 years, there was no evidence of association (P=0.86; β=0.002). The 3q25.31 locus strongly associated with newborn adiposity had no significant association with childhood adiposity suggesting that its impact may largely be limited to fetal fat accretion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fat at birth is unique to humans among primates, suggesting that a recently evolved genetic component accounts for this difference.1 Body fat accumulated during intrauterine development in humans is thought to serve as an energy source to support growth of the large human newborn brain in the early neonatal period.1 As such, subcutaneous fat provides adaptive advantages and is thought to be under positive selection. However, high or low body fat at birth is associated with increased morbidity in the first year of life as well as an increased susceptibility to poor metabolic and/or cardiovascular health later in life.2,3 While maternal fuels such as glucose and triglycerides impact fetal fat accretion, genetic factors also contribute.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 A locus between CCNL1 and LEKRI on chromosome 3 (3q25.31) was previously shown to be associated with birthweight,5 but our recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) performed in a multi-ancestry cohort of newborns revealed this locus was much more strongly associated with newborn sum of skinfolds (P=1.52 × 10−14), a measure of newborn adiposity, than with birthweight (P=5.72 × 10−7).8 The goal of the present study was to determine whether this same locus is associated with adiposity at later points during childhood.

Materials and Methods

The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study was an international multi-center epidemiologic study that examined levels of maternal glucose tolerance and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Study methods have been previously described.9 Briefly, eligible women underwent a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test between 24 and 32 weeks gestation. Using standardized methods and procedures, maternal height, weight, and blood pressure were measured, and maternal demographic information was collected. At delivery, cord blood was collected for measurement of newborn glucose, C-peptide and DNA extraction. Using standardized methods and equipment, neonatal anthropometric measurements were obtained within 72 h of birth, including head circumference, birth length, birthweight and skinfold thickness measured at the flank, triceps and subscapular regions. HAPO participants and their offspring from the Belfast, Northern Ireland center were invited to participate in the HAPO Family Study in which offspring were examined at the ages of 2 and 6 years. Measurements included weight, height, head circumference, mid-arm circumference, and triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac skinfold thickness.10 For genetic analyses, individual skinfold measurements and their sum were log transformed.

In the GWAS examining newborn size, HAPO newborns from four ancestries were genotyped using Illumina genomewide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Details of genotyping platform selection, genotype calling algorithms, quality control and imputation procedures, and estimating population substructure were previously reported.8

We examined the association of four SNPs at this locus with sum of skinfolds, a measure of adiposity, among Belfast HAPO offspring at 2 and 6 years of age using linear regression analyses (SNPTESTv2) with an additive model, adjusting for ancestry (principal components 1 and 2), newborn gender, gestational age at delivery, parity, and maternal age, body mass index (BMI), height, mean arterial blood pressure, smoking status and alcohol intake at the time of oral glucose tolerance test. Results are reported as a nominal P value and a β regression coefficient. All other analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Genotype and phenotype data were available at birth and age 2 for 293 children and at birth and age 6 for 350 children (Table 1); 270 children were common between the two cohorts. Four SNPs at the chromosome 3q25.31 locus that are in strong linkage disequilibrium (lowest pairwise r2=0.93), rs10049088, rs1482853, rs17451107 and rs900400, were previously shown to be the SNPs most highly associated with sum of skinfolds in a cohort of HAPO newborns.8 The association and direction of effect between one of these SNPs, rs900400, and sum of skinfolds as well as individual skinfold thicknesses in the cohorts of 2- and 6-year-olds from the Belfast HAPO Family Study are shown in Table 2.

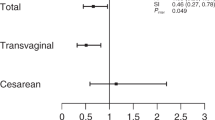

A positive association was observed between rs900400 and newborn sum of skinfolds among the 293 children in the cohort of 2-year olds (P=4.8 × 10−4; β=0.025), and 350 children in the cohort of 6-year olds (P=2.8 × 10−4; β=0.024). In contrast, at age 2 years and 6 years no association was observed between sum of skinfolds and rs900400 (P=0.06, β=−0.015 at age 2; P=0.86, β =0.002 at age 6). Although rs900400 demonstrated a marginal, albeit non-significant, association with sum of skinfolds at age 2 years, the direction of effect was opposite to that observed in the newborns.

Similar analyses were performed examining the association of rs900400 with measurements of the flank/suprailiac, triceps and subscapular skinfolds (Table 2). A positive association was observed between rs900400 and individual skinfold measurements at birth among the 293 children in the cohort of 2-year olds (triceps, P=3.4 × 10−3; subscapular, P=2.0 × 10−4; flank, P=5.0 × 10−3), and 350 children in the cohort of 6-year olds (triceps, P=1.8 × 10−3; subscapular, P=5.0 × 10-4; flank, P=1.0 × 10−3). For the suprailiac and subscapular skinfold thicknesses, an association with rs900400 was not seen at either age 2 (P=0.14 and P=0.52, respectively) or age 6 (P=0.70 and P=0.98, respectively). However, in the cohort of 2-year olds, rs900400 was weakly associated with triceps skinfold thickness at age 2 (P=0.03). However, the direction of effect was again opposite to that observed in newborns. There was no evidence for association of rs900400 with triceps skinfold thickness at age 6 (P=0.97).

Discussion

Excess adiposity at birth, which is recognized as a risk factor for peri- and postnatal complications as well as childhood obesity and adverse metabolic health outcomes during adulthood, is influenced by both environmental and genetic factors.11,12 Multiple maternal factors influence the intrauterine environment, including maternal BMI, height, blood pressure, nutrition, alcohol consumption, smoking and socioeconomic background, with maternal metabolic factors also having an important impact on fetal adiposity.11,13 In addition to maternal metabolism, fetal genetics also plays an important role in fetal fat accretion. We and others have previously used GWAS to identify genes associated with birthweight and/or newborn sum of skinfolds.5,6,8 A highly significant and reproducible finding was the association of SNPs within the chromosome 3q25.31 locus with newborn adiposity as reflected by newborn sum of skinfolds or ponderal index.5,6,8 In this report, we now demonstrate that association of this locus with measures of adiposity is no longer evident at ages 2 and 6 years, consistent with the recent observation that this locus is no longer associated with birthweight by age 2 months.6 Association of this locus with sum of skinfolds, driven primarily by skinfold thickness at the triceps, approached significance in the cohort of 2-year olds, but this association was in the opposite direction to that observed in newborns. In the cohort of 6-year olds, there was no evidence of association of rs900400 with any of the individual skinfolds. Together with the results of previous studies, these new findings suggest that genetic variation within the 3q25.31 locus contributes to fetal fat accretion but not to early childhood adiposity.

As in newborns, childhood adiposity is under both environmental and genetic control. Both low and normal birthweight newborns with rapid postnatal weight gain during the first 2 years of life have higher body fat and lower lean body mass and, during adulthood, higher body weight and fat.14,15 Prevention of rapid postnatal growth in such individuals may prevent development of an obese adult phenotype.2 Genetic variation is another important determinant of childhood adiposity. Through GWAS and related approaches, association of variants within 22 different genetic loci with childhood BMI or body weight has been demonstrated,16,17 but SNPs in the chromosome 3q25.31 locus have not been reported. Consistent with that, meta-analyses performed by the Early Growth Genetics (EGG) Consortium (www.egg-consortium.org) in European ancestry children failed to demonstrate association of rs900400 with childhood obesity (defined as BMI ⩾ 95th percentile; P=0.90).17 Similarly, a previous analysis of data from the GIANT consortium showed no evidence of association of the 3q25.31 locus with adult BMI.6

Despite the presence of high-quality genotype and phenotype data, our study had certain limitations. We have examined a small cohort of offspring from only one HAPO ancestry and, as a result, our power to demonstrate an association at age 2 and 6 years was limited. Thus, we can not rule out an association of SNPs at the chromosome 3q25.31 locus with early childhood adiposity; however, if this locus is associated with childhood adiposity, the association is much weaker than that observed during fetal life and does not alter our conclusion that the chromosome 3 locus primarily influences fetal fat accretion. Similarly, we were not able to assess directly whether this locus is associated with measures of obesity in older children and adolescents, but previous studies of the genetics of childhood obesity have failed to demonstrate an association.16,17

In summary, we have demonstrated that SNPs within the chromosome 3q25.31 locus, which exhibit strong association across multiple ancestry groups with measures of newborn adiposity,5,6,8 do not have a clear association with early childhood adiposity among European ancestry HAPO offspring.

References

Kuzawa CW . Adipose tissue in human infancy and childhood: an evolutionary perspective. Am J Phys Anthropol 1998; 27 (Suppl): 177–209.

Desai M, Beall M, Ross MG . Developmental origins of obesity: programmed adipogenesis. Curr Diab Rep 2013; 13: 27–33.

Levy-Marchal C, Jaquet D . Long-term metabolic consequences of being born small for gestational age. Pediatr Diabetes 2004; 5: 147–153.

Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1991–2002.

Freathy RM, Mook-Kanamori DO, Sovio U, Prokopenko I, Timpson NJ, Berry DJ et al. Variants in ADCY5 and near CCNL1 are associated with fetal growth and birth weight. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 430–435.

Horikoshi M, Yaghootkar H, Mook-Kanamori DO, Sovio U, Taal HR, Hennig BJ et al. New loci associated with birth weight identify genetic links between intrauterine growth and adult height and metabolism. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 76–82.

Scholtens DM, Muehlbauer MJ, Daya NR, Stevens RD, Dyer AR, Lowe LP et al. Metabolomics reveals broad-scale metabolic perturbations in hyperglycemic mothers during pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2013; 37: 158–166.

Urbanek M, Hayes MG, Armstrong LL, Morrison J, Lowe LP, Badon SE et al. The chromosome 3q25 genomic region is associated with measures of adiposity in newborns in a multi-ethnic genome-wide association study. Hum Mol Genet 2013; 22: 3583–3596.

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002; 78: 69–77.

Pettitt DJ, McKenna S, McLaughlin C, Patterson CC, Hadden DR, McCance DR . Maternal glucose at 28 weeks of gestation is not associated with obesity in 2-year-old offspring: the Belfast Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) family study. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1219–1223.

Catalano PM, Thomas A, Huston-Presley L, Amini SB . Increased fetal adiposity: a very sensitive marker of abnormal in utero development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189: 1698–1704.

Moore TR . Fetal exposure to gestational diabetes contributes to subsequent adult metabolic syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202: 643–649.

Catalano PM, Ehrenberg HM . The short- and long-term implications of maternal obesity on the mother and her offspring. BJOG 2006; 113: 1126–1133.

Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Morton SM, Pinal CS . Life-long echoes—a critical analysis of the developmental origins of adult disease model. Biol Neonate 2005; 87: 127–139.

Simmons R . Perinatal programming of obesity. Semin Perinatol 2008; 32: 371–374.

Manco M, Dallapiccola B . Genetics of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics 2012; 130: 123–133.

Bradfield JP, Taal HR, Timpson NJ, Scherag A, Lecoeur C, Warrington NM et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new childhood obesity loci. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 526–531.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the participants and research personnel of the HAPO study at the Belfast, United Kingdom center. Data on the childhood obesity trait have been contributed by EGG Consortium and have been downloaded from www.egg-consortium.org. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HD34242, HD34243, HG004415, and DK099820 and by the Diabetes UK (00022756).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chawla, R., McCance, D., McKenna, S. et al. The chromosome 3q25 locus associated with fetal adiposity is not associated with childhood adiposity. Nutr & Diabetes 4, e138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2014.35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2014.35