Abstract

Background:

Contrasting with obesity, constitutional thinness (CT) is a rare condition of natural low bodyweight. CT exhibits preserved menstruation in females, no biological marker of undernutrition, no eating disorders but a bodyweight gain desire. Anorexigenic hormonal profile with high peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) was shown in circadian profile. CT could be considered as the opposite of obesity, where some patients appear to resist diet-induced bodyweight loss.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate appetite regulatory hormones in CTs in an inverse paradigm of diet-induced weight loss.

Methods:

A 4-week fat overfeeding (2640 kJ excess) was performed to compare eight CT women (body mass index (BMI)<17.5 kg m−2) to eight female controls (BMI 18.5–25 kg m−2). Appetite regulatory hormones profile after test meal, food intake, bodyweight, body composition, energy expenditure and urine metabolomics profiles were monitored before and after overfeeding.

Results:

After overfeeding, fasting total and acylated ghrelin were significantly lower in CTs than in controls (P=0.01 and 0.03, respectively). After overfeeding, peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) and glucagon-like-peptide 1 both presented earlier (T15 min vs T30 min) and higher post-meal responses (incremental area under the curve) in CTs compared with controls. CTs failed to increase bodyweight (+0.22±0.18 kg, P=0.26 vs baseline), contrasting with controls (+0.72±0.26 kg, P=0.03 vs baseline, P=0.01 vs CTs). Resting energy expenditure increased in CTs only (P=0.031 vs baseline). After overfeeding, a significant negative difference between total energy expenditure and food intake was noticed in CTs only (−2754±720 kJ, P=0.01).

Conclusion:

CTs showed specific adaptation to fat overfeeding: overall increase in anorexigenic hormonal profile, enhanced post prandial GLP-1 and PYY and inverse to controls changes in urine metabolomics. Overfeeding revealed a paradoxical positive energy balance contemporary to a lack of bodyweight gain, suggesting yet unknown specific energy expenditure pathways in CTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The obesity epidemic is partly explained by the obesogenic environment with abundant food supply and low physical activity. However, a high proportion of obese patients appears resistant to both calorie-controlled diets and drugs intervention strategies without any pathophysiological explanation to date.1 Opposite to the high body mass index (BMI) of obesity, constitutional thinness (CT) is a natural state of underweight.2, 3, 4 CT women often consult for bodyweight gain desire. Despite similar BMI to anorexia nervosa patients (AN), CTs do not exhibit any psychological or biological features adaptive to undernutrition of AN.5 They display normal menstruation accounting for a normal nutritional status.3 In basal conditions they have a balanced energy homeostasis including food intake and total energy expenditure comparable to that of normal BMI controls. Their bodyweight remains in the lower percentiles for gender and ethnicity throughout lifetime.6

Recent studies in CT patients indicate that many features, such as gut hormones regulating energy homeostasis,7 have an opposite profile to that seen in obese patients, suggesting CT as an opposite condition to obesity. Orexigenic ghrelin is low in obese patients and increases after diet-induced bodyweight loss.8 Anorexigenic peptides such as PYY and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) are reduced/blunted in obese patients and increase after gastric by-pass surgery.9, 10, 11 In CT subjects, ghrelin is in the normal range12 and PYY is high in circadian profile.3 This anorexigenic hormone profile could be considered as a constitutive and physiological factor integrating the underweight steady state of CT12 despite living in the current obesogenic environment.

This study was designed to evaluate appetite regulatory hormones in CTs, by challenging them with a fat overfeeding paradigm, an inverse paradigm of diet-induced weight loss.13 Appetite regulatory hormones after a test meal together with bodyweight, body composition, energy balance and metabolomics adaptations were therefore assessed in a CT group of women as well as in a control group, before and after a 4-week fat overfeeding period.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Sixteen female subjects were recruited in this outpatient setting study: eight CTs among outpatients consulting for bodyweight gain desire and eight controls recruited by advertising (BMI between 18.5 and 25 kg m−2) matched by age (18–36 years). CTs exhibited the following criteria before inclusion: BMI between 13 and 17.5 kg m−2, stable bodyweight throughout post-pubertal period; no amenorrhea; no AN or other eating disorders features confirmed by psychiatric evaluation and validated psychological scales (Eating Disorders Examination (EDE), Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ));6 no under nutritional markers including normal IGF-1, estradiol, free triiodothyronine (FT3), mean cortisol and non-blunted leptin;3 no hepatic disorders and no over exercise behavior according to the MONICA optional study of physical activity (MOSPA) questionnaire.14 None of the subjects had documented chronic or congenital disease, none were taking any medication and none were smokers.

The clinical investigation was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (as revised in 1983). The local research and ethics committee of Saint-Etienne, France, approved the study and all subjects gave written informed consent before inclusion in the study. This study was registered at clinicaltrial.gov as NCT01224561.

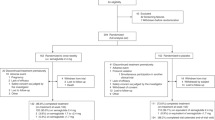

Study design and dietary intervention

Participants were first screened for their usual diet and physical activity level during the run-in period from days 1 (inclusion) to 5. Then, both groups underwent a 4-week fat overfeeding intervention in outpatient setting (from days 5 to 34) consisting in 2640 kJ (630 kcal) excess daily, enough to induce a significant bodyweight gain in controls.15 Subjects were provided with packages containing a fixed daily quantity of olive oil, peanuts, gruyere cheese and butter (31±7.4% of saturated fatty acids, 52±5.4% of mono unsaturated fatty acids and 17±2.7% of poly unsaturated) to add to their usual daily diet. They were asked to maintain their normal lifestyle (baseline diet and physical activity) during the whole study. The dietary protocol was explained by a dietician at days 1 and 5. Scheduled appointments allowed to progressively deliver food packages, evaluate bodyweight and regularly check the compliance, in order to avoid compensatory behaviors.16 Subjects were then allowed ad libitum food intake from days 34 to 62.

Each subject underwent a similar comprehensive examination at the three main visits of the study (days 5, 34 and 62): anthropomorphic analysis (bodyweight, height and body composition), energy balance evaluation, urine metabolomics analysis and appetite regulatory hormones profile assessment after test meal (for more details, see Supplementary Figure S1).

Body composition assessment

Body composition was measured at each main visit using three methods: quantification of the percentage of total body fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA),17 whole-body bioelectrical impedance (BODYSTAT Ltd; Isle of Man, UK)18 and abdominal fat area by magnetic resonance imaging (Magnetom Symphonie 1.5 Tesla; Siemens AG, Munich, Germany).19

Energy balance assessment

Food intake was evaluated using a dietary daily-self-reporting record.6 during 5 days, three times in the study (days 1–5, 17–21 and 29–34). Snacking was evaluated and defined as food eaten between the three official meals (breakfast, lunch and dinner). Over- and underreporting were tracked using Goldberg equation20, 21 and defined as follows: underreporting=energy intake (EI)/resting energy expenditure (REE)<1.4; overreporting=EI/REE>2.4.

Resting energy expenditure (REE) was measured after a 12-hour overnight fast at each main visit by indirect calorimetry (Deltatrac TM, Datex Corp., Helsinki, Finland).22 The activity energy expenditure (AEE) was measured in outpatient setting during 5 days before each main visit with an accelerometer (ACTIHEART, CamNtech, Cambridge, UK).23 Total daily energy expenditure (TEE) was calculated as follows: TEE=REE × PAL (physical activity level measured by accelerometry).24 Energy balance was estimated by calculating the energy gap as follows: Gap=TEE−daily total food intake.

Basal and test meal sampling

Venous samples were collected at 0700 hours after a 12-hour overnight fast to measure insulin, blood glucose, triglycerides, β-hydroxybutyrate, glycerol, free fatty acid (FFA), amino acid transferase (AAT), leptin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and 17 beta estradiol. Twenty-four-hour mean cortisol was also evaluated as previously described.3 Standardized test meals were performed at each main visit after a 12-hour overnight fast (1373 kJ, 328 kcal; 80% carbohydrates, 13% lipids and 7% proteins)25 and blood samples were collected at T0, 15, 30, 60 and 90 min to measure insulin, blood glucose, total and acylated ghrelin, obestatin, PYY3–36 and total GLP-1. The test meal was fully eaten between T0 min and T15 min in the presence of a study investigator. Venous blood samples were then aliquoted and collected in glass tubes containing EDTA and aprotinin, immediately cold-centrifuged and kept frozen at −80 °C. For each hormone, all samples were assayed simultaneously.

Assays

Plasma blood glucose, triglycerides, FFA, AAT, insulin, cortisol, IGF-1, leptin and 17 beta estradiol were assayed using standardized techniques.3 Obestatin, total and acylated ghrelin were determined by RIA kit (RK-031–30; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA, USA) at UMR 894 INSERM, Paris, France. Coefficients of variation for obestatin were 8 and 5% for ghrelin.26 PYY3–36 was also measured in Paris, by enzyme immunoassays kit (Phoenix, Burlingame, CA, USA) with coefficients of variation 10%26 and total GLP-1 by RIA (coefficient of variation<10%) as previously described at Imperial College, London, UK.3

Metabolomics analysis

Urinary metabolomics analysis was done at UMR 1019, Clermont-Ferrand, France.27 Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected at each main visit and homogenized. Samples (15 ml) were kept frozen at −20° C in order to be analyzed simultaneously using a reversed phase UPLC chromatography system coupled to a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (TOF MS).28 Metabolites with differential abundance between both groups and/or main visits were identified by m/z using METLIN (metlin.scripps.edu/), Human Metabolome Project (metabolomics.ca/) and KEGG ligand (genome.jp/kegg.html) databases)27, 29 (for more details, see Supplementary Method S2).

Statistical analysis

Sixteen subjects were sufficient to reveal a significant bodyweight gain with a 90% power calculation and 0.05 as an α-risk.15, 30, 31 Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Incremental area under the curve (iAUC) for gut peptides at each test meal was obtained by subtracting the rectangle corresponding to basal value multiplied by 90 min from total AUC calculated using the trapezoidal rule.

Mann–Whitney’s non-parametric tests were used to compare one-time measured characteristics including each point of test meal between the groups at each visit. Wilcoxon signed rank’s non-parametric tests were used to analyze the differences between food intake and total energy expenditure in each group at days 5 and 34.

A one-factor (time) repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze the parameters changes over the visits, including mean values of appetite regulatory hormones over each test meal and appetite regulatory hormones changes during each test meal (expressed as percentage change from baseline at each visit) in each group. Fischer’s PLSD post hoc test was performed when time effect was significant.

A two-factor (group and time) repeated measures ANOVA was also performed for metabolomics on all extracted ions using PROC-MIXED procedure of SAS software v9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Partial least square analysis (PLS) with orthogonal signal correction (OSC-PLS) was performed using SIMCAP+ v12 software (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden). Significant ions for interaction were also analyzed by hierarchical clustering analysis.32

The P-value significance threshold was set to 0.05. All these statistical analyses and graphs were performed with StatView 4.5 (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 Softwares (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

CTs were comparable to controls in both age (21.6±1.9 vs 22.1±0.8 years, P=0.6) and height (1.61±0.03 vs 1.64±0.02 m, P=0.5). CTs displayed a significantly lower bodyweight, BMI, total FM (Table 1) and plasma leptin than controls (8.3±1.4 vs 12.6±0.9 μg l−1, P=0.04), but were similar to controls for IGF1 (293±32 vs 285±18UI l−1, P=0.8), cortisol (220±18 vs 252±18 nmol l−1, P=0.5), 17 beta estradiol (70.1±8.9 vs 53.6±11.6 ng l−1, P=0.6), free T3 (3.8±0.1 vs 3.6±0.1 pmol l−1, P=0.8), fat and liver assessments (AAT: 24.5±1.3 vs 28.5±2.8UI l−1, P=0.4). Psychological scores showed no eating-disorder-related traits such as perfectionism, drive to thinness or excessive bodyweight/shape concern in CTs compared with controls. Moreover CTs exhibited lower restrained eating scores than controls (EDE score: 1.2±0.5 vs 4.6±1.2, P=0.03; DEBQ score: 12.9±1.8 vs 26.3±2.7, P=0.010; Table 1).

Dietary intervention monitoring

Daily energy intake and macronutrient distribution did not differ between the groups at any visits. Daily energy intake significantly increased after overfeeding compared to baseline in both groups. Analysis of daily meals distribution showed a significantly higher percentage of snacking in CTs compared with controls at baseline (P=0.045) and on day 34 (P=0.002) (for more details, see Supplementary Table S3). Monitored as markers of dietary intervention, triglycerides and FFA tended to increase on day 34 in both groups, and returned to baseline values on day 62. According to Goldberg equation, no over-reporting (EI/REE>2.4) was noted in CTs (EI/REE=2.1±0.1) nor in controls (EI/REE=1.7±0.1) at the end of the overfeeding period (Table 1).

Effect of fat overfeeding on bodyweight

At the end of the overfeeding period (day 34), mean bodyweight of CTs was not different from baseline (+0.225±0.180 kg, P=0.26 vs baseline), whereas controls’ mean bodyweight was significantly increased compared with baseline value (+0.725±0.268 kg, P=0.03 vs baseline). On day 62, CTs’ mean bodyweight was decreased (−0.600±0.224 kg, P=0.02 vs day 34), while mean bodyweight gain remained significantly elevated in controls (+0.800±0.281 kg, P=0.02 vs baseline and P=0.75 vs day 34). Individual data for BMI are presented in Supplementary Figure S4 (Table 1).

Effect of fat overfeeding on appetite regulatory hormones

Total GLP-1

iAUC for GLP-1 remained stable in CTs and tended to decrease in controls after overfeeding (Figure 1). At day 34, iAUC for GLP-1 was higher in CTs than in controls (P=0.05; Figure 1a).

GLP-1 and PYY post-test meal kinetic changes. Post-test meal kinetic changes in anorexigenic gut hormones before overfeeding (day 5), at the end of the 2640 kJ (630 kcal) per day excess overfeeding period (day 34) and after ad libitum food intake period (day 62) in the CT group (n=8, dotted line) and the control group (controls, n=8, plain line). Standardized test meal (1373 kJ (328 kcal); 80% carbohydrates, 13% lipids and 7% proteins) was served and eaten between T0 min and 15 min. (a) iAUC for total GLP-1 expressed as pmol per l.90 min at each test meal (days 5, 34 and 62). (b) iAUC for PYY3–36 expressed as pg ml−1 per 90 min at each test meal. (c) Kinetic changes of total GLP-1 after test meal expressed as percentage change from baseline (T0) on days 5, (d) 34 and (e) 62. (f) Kinetic changes of PYY3–36 after test meal on days 5, (g) 34 and (h) 62. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis: *P<0.05 vs T0 min in each group; $P<0.05 between CTs and controls.

Kinetic change analysis: at baseline, GLP-1 surged at T30 min (P<0.05 vs T0 min) in both groups (Figure 1c). After overfeeding, the surge in total GLP-1 occurred earlier at T15 min (P=0.03 vs T0) in both groups and GLP-1 increment persisted in CTs over the rest of the test meal (Figure 1d). This surge remained earlier at T15 min in both groups at day 62 (Figure 1e).

PYY3–36

IAUC for PYY3–36 also remained stable in CTs and decreased in controls after overfeeding (P=0.05). At day 34, iAUC for PYY3–36 was higher in CTs than in controls (P=0.02; Figure 1b).

Kinetic change analysis: at baseline, PYY3–36 surged at T30 min in CTs (P<0.05 vs T0 min) and at T60 min in controls (P<0.05 vs T0 min; Figure 1f). On days 34 and 62, CTs exhibited an earlier surge compared with baseline, at T15 min (P<0.05 vs T0 min; Figures 1g and h). No surge was observed in controls at day 34.

Ghrelin/obestatin

Fasting plasma levels of total (785±43 pg ml−1 at day 34 vs 770±62 pg ml−1 at day 5, P=0.6) and acylated ghrelin (195±25 pg ml−1 at day 34 vs 255±32 pg ml−1 at day 5, P=0.4) were not modified by overfeeding in CTs. Fasting total (914±73 pg ml−1 at day 34 vs 711±20 pg ml−1 at day 5, P=0.01) and acylated ghrelin (321±39 pg ml−1 at day 34 vs 204±21 pg ml−1 at day 5, P=0.03) increased after overfeeding in controls. Fasting total and acylated ghrelin were lower in CTs than in controls on day 34 (P=0.01 and 0.03, respectively).

IAUC for total and acylated ghrelin increased in CTs (P=0.03) and decreased in controls (respectively P=0.03 and 0.02) after overfeeding. At day 34, iAUC for total and acylated ghrelin were higher in CTs than in controls (respectively P=0.02 and 0.02; Figures 2a and b).

Ghrelin/obestatin post-test meal kinetic changes. Post-test meal kinetic changes in ghrelin/obestatin before overfeeding (day 5), at the end of the 2640 kJ (630 kcal) per day excess overfeeding period (day 34) and after ad libitum food intake period (day 62) in the CT group (n=8, dotted line) and the control group (controls, n=8, plain line). Standardized test meal (1373 kJ (328 kcal); 80% carbohydrates, 13% lipids and 7% proteins) was served and eaten between T0 min and 15 min. (a) iAUC for total ghrelin expressed as pg ml−1 per 90 min at each test meal (days 5, 34 and 62). (b) iAUC for acylated ghrelin expressed as pg ml−1 per 90 min at each test meal. (c) iAUC for obestatin expressed as mg ml−1 per 90 min at each test meal. (d) Kinetic changes in total ghrelin after test meal expressed as percentage change from baseline (T0) on days 5, (e) 34 and (f) 62. (g) Kinetic changes in acylated ghrelin after test meal on days 5, (h) 34 and (i) 62. (j) Kinetic changes in obestatin after test meal on days 5, (k) 34 and (l) 62. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis: *P<0.05 vs T0 min in each group; $P<0.05 between CTs and controls.

Kinetic change analysis: at baseline, total and acylated ghrelin tended to be suppressed by the meal in both groups (Figures 2d and g). After overfeeding, total and acylated ghrelin were significantly suppressed by the meal at T30 min (P=0.02 and 0.03 vs T0 min, respectively) in controls but were not modified in CTs (Figures 2e and h). On day 62, total and acylated ghrelin were significantly suppressed by the meal in both groups at 30 min (P=0.02; Figures 2f and i). Obestatin was significantly suppressed by the meal at each visit in both groups at the three visits (Figures 2j–l).

Effect of fat overfeeding on energy balance

REE and REE/FFM significantly increased in CTs on day 34 compared with baseline (P=0.03 and P=0.04 respectively), and returned to baseline on day 62 (P=0.67 and P=0.16 respectively). No significant change in REE and REE/FFM was detected in controls on days 34 or 62. AEE was comparable between groups at each visit and was not modified by the overfeeding (Table 1). At baseline, no difference was noticed between TEE and daily energy intake in both groups, showing a balanced energy homeostasis. At the end of the overfeeding, the difference between TEE and food intake (energy gap) was significant in CTs (P=0.01), whereas it remained non-significant in controls. Energy gap significantly increased in CTs during the overfeeding (P=0.04 vs baseline), whereas it remained stable in controls (P=0.35 vs baseline; Table 1 and Figure 3).

Energy balance. Energy balance before overfeeding (day 5), at the end of the 2640 kJ (630 kcal) per day excess overfeeding period (day 34) and after ad libitum food intake period (day 62) in the CT group (n=8) and the control group (controls, n=8). Total daily energy expenditure (grey bars) was calculated as follows: TEE=REE × physical activity level. The physical activity level was evaluated with an accelerometer. Food intake (white bars) was evaluated with a daily dietary record completed for 5 days. The energy gap (striped boxes) was calculated as follows: TEE−food intake. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis: *P<0.05 between TEE and food intake. 1NS=non-significant. a indicates P<0.05 vs day 5.

Effect of fat overfeeding on urine metabolomics analysis

A total of 3 243 ions were extracted from urine analysis, including 94 ions significant for group effect, 84 ions for time effect and 542 ions for interaction effect (Figure 4). After noise reduction, OSC-PLS discriminated both group (axe 2) and interaction effect (axe 1), with a good fit of the models (R2Y=0.65, Q2cum=0.62). Results show a good discrimination of urine metabolomics at day 34, suggesting an important metabolic modification at this time for both groups with larger amplitude for CTs (Figure 4a).

Metabolomics urine analysis. Metabolomics urine analysis before overfeeding (day 5), at the end of the 2640 kJ (630 kcal) per day excess overfeeding period (day 34) and after ad libitum food intake period (day 62) in the CT group (n=8) and the control group (controls, n=8). (a) PLS analysis with orthogonal signal correction (OSC-PLS) score plots of component 1 vs component 2 showing the group × time effect (CT34 R2cum=0.62, CT34 Q2cum=0.62). Day 5 controls are in red, day 34 controls in green, day 62 controls in blue, day 5 CTs in black, day 34 CTs in pink and day 62 CTs in orange. (b) Heatmap representing a hierarchical clustering analysis of the samples (group × time) and significant ions for interaction. The blue color corresponds to the highest value and yellow color to the lowest ones.

When analyzed by hierarchical clustering analysis, two clusters with opposite profiles were found (heatmap, Figure 4b): one cluster included CTs on days 5 and 62 and controls on day 34 with the highest values (blue color) for the majority of the ions. The other cluster included controls on days 5 and 62 and CTs on day 34 with the lowest values (yellow color). For each group, metabolomics on day 62 was not significantly different from baseline showing a return to the initial state. During the overfeeding period measured on day 34, each metabolomics phenotype switched to the other group. We observed a significant decrease in identified metabolites in CTs, whereas an increase in controls, including metabolites from mitochondria such as phenylalanine (P=0.01), tyrosine (P=0.005) and xanthurenic acid (P=0.001), and metabolites involved in FFA metabolism such as carnitine (P=0.03; for more details, see Supplementary Figure S5).

Discussion

CT is a rare condition of natural low bodyweight, with no sign of undernutrition and no eating disorders but a bodyweight gain desire. However, they seem to fail gaining bodyweight. Previous static evaluation of appetite regulatory hormones in CTs showed an overall anorexigenic tone that may contribute to their low stable bodyweight.12 We therefore designed this study in a dynamic perspective by challenging CTs with a fat overfeeding. CTs displayed an enhanced anorexigenic response associated to a lack of bodyweight gain.

Indeed, overfeeding induced an earlier and longer surge of PYY and GLP-1 in CTs, associated with lower fasting ghrelin levels compared with controls. The post-prandial response in PYY and total GLP-1 in CTs could account for an earlier and stronger satiety signal. These data are consistent with CTs’ dietary records revealing smaller-portioned meals and more snacking at baseline and after overfeeding. The link between snacking and bodyweight is not clear, recent data suggesting snacking is not necessarily associated with overweight.33 This particular eating behavior could be adaptive in this thin population in order to ensure enough adequate daily energy intake. Secondly, CT could be considered as the opposite to obesity with regards to this particular satiety profile, as GLP-1 and PYY post meal responses are blunted in obese people9, 10 and orexigenic tone increases after diet-induced bodyweight loss.8

Ghrelin showed a physiological post-prandial fall34 in controls, except for the first test meal, perhaps due to a possible stress at the first visit.35 On the opposite, the fall of ghrelin was blunted in CTs before and after overfeeding. It could be surprising as post-prandial fall of ghrelin is blunted in obese patients.36, 37 The inability of food to suppress ghrelin in CTs after the overfeeding may be due to the already low fasting plasma level at that moment compared with controls, also accounting for this anorexigenic tone. It could also be due to an adaptive orexigenic reaction to the enhanced surge in PYY and GLP-1.

In obesity, some authors propose the adaptive orexigenic reaction during diet-induced weight loss as responsible for the relapse after restrictive diet.8 By contrast, we hypothesize that enhanced anorexigenic/satietogenic tone found in CT after a supervised overfeeding could make them less prone to maintain longer overfeeding.

Importantly, CTs did not gain bodyweight after overfeeding. Moreover, the increase in oxygen consumption rate and the decrease in carbohydrate oxidation index accounted for a low fat storage in CTs (Table 1). This adaptive behavior contemporary to a lack of bodyweight gain markedly contrasts the expected increase in bodyweight and FM observed in controls, often called ‘lean’ in the literature.13, 15, 38 In parallel, hierarchical clustering analysis analysis of metabolomics data revealed opposite changes in global clusters between the two groups of subjects (heatmap Figure 4b), suggesting the involvement of different/inverse metabolic pathways in response to the same dietary stress including mitochondria and FFA metabolism.39 It could indeed suggest a diverse mitochondria metabolism in both groups in response to overfeeding, as phenylalanine, tyrosine and xanthurenic acid are differentially modified by overfeeding between the groups.40 Moreover the opposite carnitine-level change in urinary metabolomics could suggest an opposite mitochondrial carnitine shuffle in response to overfeeding.41 These metabolites could be considered as fingerprints of a different metabolomics pathway used by the groups.42

Bodyweight changes are related to energy imbalance. As a resistance to bodyweight gain was observed in CTs during overfeeding, one might presume an overreaction of energy expenditure mechanisms. This hypothesis is also supported by gut hormones profiles and changes in CTs. Thus, transgenic mice overexpressing PYY exposed to high-fat diet showed increased thermogenesis43 and recent studies of infusion of PYY44 and GLP-1 in humans showed increased REE.45

In the current study, the significant increase in CTs’ REE observed during the overfeeding period can be proposed as an adaptive response to the fat overfeeding in order to maintain their low bodyweight. According to the literature, in basal conditions, REE in CTs, similar to that of controls, seems to be related to BAT FDG uptake.46 Although difficult to isolate, the part of BAT activity within REE's rise in CTs after overfeeding remains to be studied.

However, despite the increase of REE, CTs had a positive energy balance by the end of the overfeeding period (that is, a higher food intake than TEE) while paradoxically not gaining bodyweight. Interestingly, a negative energy balance, the opposite to that seen in CTs, has been described previously in some obese patients, for whom, even after adjustment for underestimation of food intake and potential overestimated physical activity, the energy balance remained negative.47 Further studies comparing opposite diet interventions (CTs compared with controls exposed to overfeeding/obese patients compared with controls exposed to food restriction) might be useful to compare these gaps. Altogether, these data support the hypothesis that CT’s adaptive hormonal profile to overfeeding may select a particular energy expenditure pathway to prevent them from bodyweight gain. The ‘3500 kcal per pound’ rule, recently questioned and debated,48 cannot be applied to CT with regards to these data. This study provides another example of a specific population using a specific energy pathway, partly explaining conflicting interpretation of energy balance and needs therefore further studies to confirm it.

The paradoxical gap between energy intake and energy expenditure found in CTs may raise questions on the accuracy of usual techniques of energy balance evaluation.48 While AEE measured by accelerometer did not change after overfeeding, the increase of total energy expenditure in CTs might be specifically underestimated, at least in terms of non-exercise activity thermogenesis,49 fidgeting50 and/or subclinical steatorrhea due to fat overfeeding.51 Further studies with calorimetric chambers or doubly labeled water tests could evaluate these parameters. Finally, CTs’ compliance to the dietary protocol might be questioned, especially as there is no reliable method to measure energy intake in human. However, food questionnaires even if controversial are widely used. Besides, several indirect markers such as lipid plasma levels were modified by overfeeding in CTs. A metabolomics trajectory52 was observed in both groups with significant changes in response to overfeeding (Figure 3a), suggesting that a dietary intervention was performed in both groups. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that CTs complied with the study protocol. Recent mathematical models proposed to predict weight gain/loss in response to dietary intervention53 should be used to test compliance in further studies.

Conclusion

This study showed specific changes to a 4-week fat overfeeding in the particular CT population. The increase in the anorexigenic hormonal tone in response to the supervised overfeeding may partly prevent CTs from gaining bodyweight and may explain CTs’ food behaviors. CTs failed to gain bodyweight and seem to use particular energy pathways. This study reveals that CTs exhibit a paradoxical positive energy balance, opposite to the paradoxical negative energy balance in obesity, suggesting a possible resistance to bodyweight gain in CT and to bodyweight loss in obesity. Understanding this energetic adaptation to overfeeding in CT could provide explanations on the mechanisms underlying resistance to bodyweight loss in obesity.

References

Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Smith SR, Ryan DH, Anton SD et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 859–873.

Tolle V, Kadem M, Bluet-Pajot MT, Frere D, Foulon C, Bossu C et al. Balance in ghrelin and leptin plasma levels in anorexia nervosa patients and constitutionally thin women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 109–116.

Germain N, Galusca B, Le Roux CW, Bossu C, Ghatei MA, Lang F et al. Constitutional thinness and lean anorexia nervosa display opposite concentrations of peptide YY, glucagon-like peptide 1, ghrelin, and leptin. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 85: 967–971.

Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995; 854: 1–452.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994.

Bossu C, Galusca B, Normand S, Germain N, Collet P, Frere D et al. Energy expenditure adjusted for body composition differentiates constitutional thinness from both normal subjects and anorexia nervosa. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007; 292: E132–E137.

Bloom S . Hormonal regulation of appetite. Obes Rev 2007; 8 (Suppl 1): 63–65.

Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, Breen PA, Ma MK, Dellinger EP et al. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1623–1630.

Verdich C, Toubro S, Buemann B, Lysgard Madsen J, Juul Holst J, Astrup A . The role of postprandial releases of insulin and incretin hormones in meal-induced satiety—effect of obesity and weight reduction. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1206–1214.

le Roux CW, Batterham RL, Aylwin SJ, Patterson M, Borg CM, Wynne KJ et al. Attenuated peptide YY release in obese subjects is associated with reduced satiety. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 3–8.

Ranganath LR, Beety JM, Morgan LM, Wright JW, Howland R, Marks V . Attenuated GLP-1 secretion in obesity: cause or consequence? Gut 1996; 38: 916–919.

Germain N, Galusca B, Grouselle D, Frere D, Tolle V, Zizzari P et al. Ghrelin/obestatin ratio in two populations with low bodyweight: constitutional thinness and anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009; 34: 413–419.

Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Despres JP, Nadeau A, Lupien PJ, Theriault G et al. The response to long-term overfeeding in identical twins. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 1477–1482.

Iqbal R, Rafique G, Badruddin S, Qureshi R, Gray-Donald K . Validating MOSPA questionnaire for measuring physical activity in Pakistani women. Nutr J 2006; 5: 18.

Meugnier E, Bossu C, Oliel M, Jeanne S, Michaut A, Sothier M et al. Changes in gene expression in skeletal muscle in response to fat overfeeding in lean men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15: 2583–2594.

Stubbs RJ, Whybrow S . Energy density, diet composition and palatability: influences on overall food energy intake in humans. Physiol Behav 2004; 81: 755–764.

Mazess RB, Barden HS, Bisek JP, Hanson J . Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for total-body and regional bone-mineral and soft-tissue composition. Am J Clin Nutr 1990; 51: 1106–1112.

Lukaski HC, Johnson PE, Bolonchuk WW, Lykken GI . Assessment of fat-free mass using bioelectrical impedance measurements of the human body. Am J Clin Nutr 1985; 41: 810–817.

Armao D, Guyon JP, Firat Z, Brown MA, Semelka RC . Accurate quantification of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) using water-saturation MRI and computer segmentation: preliminary results. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 23: 736–741.

Black AE . Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake: basal metabolic rate. A practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int. J Obes 2000; 24: 1119.

Johansson L, Solvoll K, Bjørneboe GE, Drevon CA . Under- and overreporting of energy intake related to weight status and lifestyle in a nationwide sample. Am J Clin Nutr 1998; 68: 266–274.

Ferrannini E . The theoretical bases of indirect calorimetry: a review. Metabolism 1988; 37: 287–301.

Crouter SE, Churilla JR, Bassett Jr DR . Accuracy of the Actiheart for the assessment of energy expenditure in adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008; 62: 704–711.

Kurpad AV, Raj R, Maruthy KN, Vaz M . A simple method of measuring total daily energy expenditure and physical activity level from the heart rate in adult men. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005; 60: 32–40.

Greenman Y, Golani N, Gilad S, Yaron M, Limor R, Stern N . Ghrelin secretion is modulated in a nutrient- and gender-specific manner. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004; 60: 382–388.

Germain N, Galusca B, Grouselle D, Frere D, Billard S, Epelbaum J et al. Ghrelin and obestatin circadian levels differentiate bingeing-purging from restrictive anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 3057–3062.

Pereira H, Martin J-F, Joly C, Sébédio J-L, Pujos-Guillot E . Development and validation of a UPLC/MS method for a nutritional metabolomic study of human plasma. Metabolomics 2010; 6: 207–218.

Roux A, Xu Y, Heilier J-Fo, Olivier M-Fo, Ezan E, Tabet J-C et al. Annotation of the human adult urinary metabolome and metabolite identification using ultra high performance liquid chromatography coupled to a linear quadrupole ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal Chem 2012; 84: 6429–6437.

Walsh MC, Brennan L, Pujos-Guillot E, Sébédio J-L, Scalbert A, Fagan A et al. Influence of acute phytochemical intake on human urinary metabolomic profiles. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86: 1687–1693.

Shea J, French CR, Bishop J, Martin G, Roebothan B, Pace D et al. Changes in the transcriptome of abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue in response to short-term overfeeding in lean and obese men. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 407–415.

Horton TJ, Drougas H, Brachey A, Reed GW, Peters JC, Hill JO . Fat and carbohydrate overfeeding in humans: different effects on energy storage. Am J Clin Nutr 1995; 62: 19–29.

Fardet A, Llorach R, Martin J-Fo, Besson C, Lyan B, Pujos-Guillot E et al. A liquid chromatography−quadrupole time-of-flight (LC−QTOF)-based metabolomic approach reveals new metabolic effects of catechin in rats fed high-fat diets. J Proteome Res 2008; 7: 2388–2398.

Keast DR, Nicklas TA, O'Neil CE . Snacking is associated with reduced risk of overweight and reduced abdominal obesity in adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92: 428–435.

Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS . A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 2001; 50: 1714–1719.

Stengel A, Wang L, Tache Y . Stress-related alterations of acyl and desacyl ghrelin circulating levels: mechanisms and functional implications. Peptides 2011; 32: 2208–2217.

English PJ, Ghatei MA, Malik IA, Bloom SR, Wilding JP . Food fails to suppress ghrelin levels in obese humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 2984.

le Roux CW, Patterson M, Vincent RP, Hunt C, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR . Postprandial plasma ghrelin is suppressed proportional to meal calorie content in normal-weight but not obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 1068–1071.

Bouchard C, Tchernof A, Tremblay A . Predictors of body composition and body energy changes in response to chronic overfeeding. Int J Obes 2014; 38: 236–242.

Gibney MJ, Walsh M, Brennan L, Roche HM, German B, van Ommen B . Metabolomics in human nutrition: opportunities and challenges. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 82: 497–503.

Civitarese AE, Smith SR, Ravussin E . Diet, energy metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2007; 10: 679–687.

Rinaldo P, Matern D, Bennett MJ . Fatty acid oxidation disorders. Ann Rev Physiol 2002; 64: 477–502.

Fernie AR, Trethewey RN, Krotzky AJ, Willmitzer L . Metabolite profiling: from diagnostics to systems biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004; 5: 763–769.

Boey D, Lin S, Enriquez RF, Lee NJ, Slack K, Couzens M et al. PYY transgenic mice are protected against diet-induced and genetic obesity. Neuropeptides 2008; 42: 19–30.

Sloth B, Holst JJ, Flint A, Gregersen NT, Astrup A . Effects of PYY1-36 and PYY3-36 on appetite, energy intake, energy expenditure, glucose and fat metabolism in obese and lean subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007; 292: E1062–E1068.

Tan TM, Field BC, McCullough KA, Troke RC, Chambers ES, Salem V et al. Coadministration of glucagon-like Peptide-1 during glucagon infusion in humans results in increased energy expenditure and amelioration of hyperglycemia. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1131–1138.

Pasanisi F, Pace L, Fonti R, Marra M, Sgambati D, De Caprio C et al. Evidence of brown fat activity in constitutional leanness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: 1214–1218.

Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, Pestone M, Dowling H, Offenbacher E et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1893–1898.

Hall KD, Heymsfield SB, Kemnitz JW, Klein S, Schoeller DA, Speakman JR . Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 95: 989–994.

Levine JA, Eberhardt NL, Jensen MD . Role of nonexercise activity thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain in humans. Science 1999; 283: 212–214.

Johannsen DL, Ravussin E . Spontaneous physical activity: relationship between fidgeting and body weight control. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2008; 15: 409–415.

Heizer WD . Normal and abnormal intestinal absorption by humans. Environ Health Perspect 1979; 33: 101–106.

Winnike JH, Busby MG, Watkins PB, O'Connell TM . Effects of a prolonged standardized diet on normalizing the human metabolome. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90: 1496–1501.

Hall KD . Predicting metabolic adaptation, body weight change, and energy intake in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010; 298: E449–E466.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Lang (Psychiatry, CHU Saint-Etienne) for psychiatric evaluation; Professor Laville (Human Nutrition Research Center Rhône-Alpes) and Dr Vidal (INSERM unit 1060/CarMen) for their support; Professor Barral for the MRI analysis; Ms Mure for the food intake records analysis; Ms Cuenco Shillito and Professor Ghatei for the GLP-1 assay and Dr D Grouselle for ghrelin assays. This work was supported by regional innovation and research committee grant (PHRC no. 0701047). This study is registered in Clinical Trial.gov (no. NCT01224561).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Nutrition & Diabetes website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Germain, N., Galusca, B., Caron-Dorval, D. et al. Specific appetite, energetic and metabolomics responses to fat overfeeding in resistant-to-bodyweight-gain constitutional thinness. Nutr & Diabetes 4, e126 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2014.17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2014.17

This article is cited by

-

Systematic review of prospective studies assessing risk factors to predict anorexia nervosa onset

Journal of Eating Disorders (2023)

-

Challenges of considering both extremities of the weight status spectrum to better understand obesity: insights from the NUTRILEAN project in constitutionally thin individuals

International Journal of Obesity (2023)

-

Obesity, but not high-fat diet, is associated with bone loss that is reversed via CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs-mediated gut microbiome of non-obese mice

npj Science of Food (2023)

-

The Influence of Energy Balance and Availability on Resting Metabolic Rate: Implications for Assessment and Future Research Directions

Sports Medicine (2023)

-

Underweight but not underfat: is fat-free mass a key factor in constitutionally thin women?

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2021)