Key Points

-

Active surveillance (AS) is broadly described as a management option for men with low-risk prostate cancer, but semantic heterogeneity exists in the literature and guidelines

-

An urgent need for uniform terminology exists to establish active communication and collaboration between research groups around the world

-

Agreement between international experts has been reached on 61 relevant terms and subsequent definitions regarding AS for patients with localized prostate cancer

-

This standard terminology could support multidisciplinary communication, reduce the extent of variation in clinical practice and optimize clinical decision making

Abstract

Active surveillance (AS) is broadly described as a management option for men with low-risk prostate cancer, but semantic heterogeneity exists in both the literature and in guidelines. To address this issue, a panel of leading prostate cancer specialists in the field of AS participated in a consensus-forming project using a modified Delphi method to reach international consensus on definitions of terms related to this management option. An iterative three-round sequence of online questionnaires designed to address 61 individual items was completed by each panel member. Consensus was considered to be reached if ≥70% of the experts agreed on a definition. To facilitate a common understanding among all experts involved and resolve potential ambiguities, a face-to-face consensus meeting was held between Delphi survey rounds two and three. Convenience sampling was used to construct the panel of experts. In total, 12 experts from Australia, France, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Japan, the UK, Canada and the USA participated. By the end of the Delphi process, formal consensus was achieved for 100% (n = 61) of the terms and a glossary was then developed. Agreement between international experts has been reached on relevant terms and subsequent definitions regarding AS for patients with localized prostate cancer. This standard terminology could support multidisciplinary communication, reduce the extent of variations in clinical practice and optimize clinical decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Active surveillance (AS) is an accepted option for the initial management of carefully selected men with localized, well-differentiated prostate cancer who are thought to have a low risk of progression1,2,3,4. AS is broadly described as a management option for patients with low-risk prostate cancer, which involves the postponement or avoidance of invasive treatment, with a switch to curative treatment if evidence is obtained that the patient has an increased risk of disease progression or if the patient expresses preference for it. However, semantic heterogeneity exists in the literature and guidelines. For instance, the specific definitions of the terms AS and watchful waiting (WW) are inconsistent in the published literature and can elicit considerable confusion. The terms AS and WW are frequently used interchangeably, but they refer to very different observational approaches. AS involves the avoidance or postponement of immediate therapy combined with careful surveillance; definitive treatment is then offered if there is evidence that the patient is at increased risk of disease progression4. AS differs from WW, which is based upon the premise that men will not benefit from definitive treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer owing to limited life expectancy, comorbidity, and the prolonged natural history of the prostate cancer4. Patients managed using a WW protocol undergo observation consisting of a lesser degree of monitoring than those on AS might receive, and in which palliative treatment is generally instituted if metastases or local symptoms develop. Interpreting and comparing research results is difficult owing to the nonstandardized use of the terms AS and WW and their intended and often mixed treatment objectives (curative or palliative)5.

This semantic heterogeneity is also reflected in AS guidelines6. In these guidelines, AS is primarily recommended for patients with low-risk tumours; however, these guidelines contain various definitions of low-risk prostate cancer, as specified by different combinations of clinical criteria including clinical and pathological characteristics (such as tumour stage, serum PSA levels, biopsy Gleason score, tumour volume and serum PSA density). Furthermore, definitions of disease reclassification and progression differ among published guidelines and multiple criteria for initiation of curative treatment are proposed6.

Problems resulting from the use of ambiguous language include hindered clinical decision making, particularly in multidisciplinary collaborations, and limited opportunities for research7. Moreover, such ambiguity has raised a barrier that hampers exchange of knowledge within and between fundamental domains of research and research groups8. An urgent need exists for uniform terminology to help clarify scientific discourse: that is, we need to speak the same language. The primary purpose of this study was to reach international consensus on definitions of terms that are often used in AS undertaken for carefully selected men with localized, well-differentiated prostate cancer.

Methods used to develop definitions

Expert panel. Convenience sampling was used to construct the panel of experts. The Movember Foundation's Global Action Plan Active Surveillance (GAP3) project is an integrated project lasting 30 months that is being implemented across 14 countries in the five Movember regions (Australasia, Europe, the UK, Canada, the USA)9. Milestones of the project include the development of a global AS database for clinical, biospecimen, imaging and biomarker data, worldwide, tailor-made guidelines on AS and a web-based AS platform for patients and providers. The experts for the panel were selected within the Movember Foundation's GAP3 consortium (Box 1), consisting of urologists, acclaimed scientists, a pathologist and radiation oncologists with expertise in the field of AS. We aimed at including at least one expert per participating institute (currently, n = 15) in the GAP3 consortium. Eligible experts were invited by e-mail to participate in the study. After participating, the experts were asked to provide personal information, such as their specialty8.

List of terms. As part of the GAP3 initiative, a narrative review of available AS guidelines provided a comprehensive overview of recommendations regarding patient selection, frequency and type of monitoring and the criteria for initiation of definitive treatment6. This review has been used as a starting point to produce a list of potentially important terms (led by Sophie Bruinsma, a researcher in the field of prostate cancer). Subsequently, this list has been critically reviewed by Monique J. Roobol (an epidemiologist) and Chris H. Bangma (a urologist), from Erasmus MC, the Netherlands, who are experts in the field of prostate cancer, and items were added if considered needed. In total, the initial list addressed 53 individual items.

Procedure for determining definitions

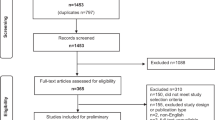

Consensus definitions were derived using a Delphi method. The Delphi method is a widely accepted technique of structured and systematic information gathering from a group of experts (termed the Delphi Panel) on a specific topic using a series of questionnaires10. The Delphi method enables a panel of experts to provide insights and opinions, even when they are not located in the same geographic area. According to this formal consensus-building method, participants were asked to fill out an iterative sequence of surveys, in this case in the form of online questionnaires. The current study uses a modified Delphi method, in which online surveys were combined with a physical meeting of the panel of experts (Fig. 1).

The Delphi method is a widely accepted technique of structured and systematic information gathering from a group of experts (termed the Delphi Panel) on a specific topic using a series of questionnaires. The Delphi method enables a panel of experts to provide insights and opinions, even when they are not located in the same geographic area. The current study uses a modified Delphi method, in which an iterative sequence of online surveys were combined with a physical meeting of the panel of experts

In the first round, the experts were asked to provide definitions of 53 terms related to AS for low-risk prostate cancer according to their personal opinion. These experts were informed that this list might not be exhaustive and were asked to add potentially missing items and their corresponding definitions to the list at the end of the survey. The open comments made by the experts were carefully considered by the referee group8, consisting of Bruinsma and Roobol, and, based on the input of the experts, temporary definitions were formulated and clustered into themes. These temporary definitions were presented to the experts in a second-round survey and they were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the proposed definitions; if they did not agree with a certain definition, the experts were asked to clearly state why. Consistent with other studies11,12,13, consensus was considered to be reached if ≥70% of the experts agreed on a definition8. If consensus was achieved on definitions, these were added to the AS dictionary or glossary of terms (hereafter, referred to as the glossary) (Table 1). Subsequently, to facilitate a common understanding among all experts involved and to resolve potential ambiguities, a consensus, in-person meeting was held, which was attended by representatives from the majority of the countries participating in the GAP3 consortium (the third round). This meeting was organized in conjunction with the annual conference of the European Association of Urology (EAU) in March 2016, hosted in Munich (Germany). During this meeting, the majority of the terms and subsequent definitions on which no consensus had been reached in the previous surveys were further discussed by the experts. Based on the second survey and the input of the experts during the face-to-face consensus meeting, a third and final survey was designed (the fourth round). This final survey consisted of: terms and subsequent definitions on which no consensus had been reached in the second survey, and were adapted based on the input of the experts from this survey; terms and subsequent definitions on which no consensus was reached in the second survey, that were discussed during the consensus meeting, and subsequently adapted based on the experts' input at the consensus meeting; and terms and subsequent definitions on which consensus was reached in the second survey, but were adapted based on suggestions for improvement from the experts in the second survey. We asked the experts whether they agreed or disagreed with the formulated consensus definitions. If they did not agree with a certain definition, the experts were asked to clearly state why they did not agree with the proposed definition. Consensus was considered to be reached if ≥70% of the experts agreed on a definition. Consensus definitions were added to the glossary (Table 1).

Survey administration. Three rounds of surveys were conducted between January 2016 and April 2016. The experts were given ∼2 weeks to complete each survey round, and several reminder e-mails were sent. In the first round, the preliminary survey was sent to all experts. The second-round survey was only sent to the responders from the initial round. All experts who responded to the first and second survey were permitted to participate in the consensus meeting (third round). The third and final survey (round four) was disseminated to all participants from round two and to those present at the consensus meeting who did not participate in round two.

Results of the consensus initiative

Participation of experts. In total, 17 experts from the 15 participating institutions were invited to take part in the first-round survey, of which 14 completed the survey and three did not respond to the invitation. These 14 experts were invited to complete the second-round survey, of which 10 responded and four did not respond to the invitation. In total, seven of the 10 experts who responded to the second survey were present at the consensus meeting (round three). In addition, two experts who participated in the first-round survey but not in the second-round survey were present at the consensus meeting and participated in the semantics discussion. The 10 experts who participated in the second survey and were also present at the consensus meeting, and the experts who participated only in the first round survey and were present at the consensus meeting were invited for the third and final survey (round four). In total, 12 experts were invited, all of whom participated (Fig. 2, Table 2 and Supplementary information S1 (table)).

In total, 17 experts from the 15 participating institutions were invited to take part in the first-round survey, of which 14 completed the survey and three did not respond to the invitation. These 14 experts were invited to complete the second-round survey, of which 10 responded and four did not respond to the invitation. In total, seven of the 10 experts who responded to the second survey were present at the consensus meeting (round 3). In addition, two experts who participated in the first-round survey but not in the second-round survey were present at the consensus meeting and participated in the semantics discussion. The 10 experts who participated in the second survey and were also present at the consensus meeting, and the experts who participated only in the first round survey and were present at the consensus meeting were invited for the third and final survey (round 4). In total, 12 experts were invited, all of whom participated making up the final expert panel. GAP3; Global Action Plan Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance.

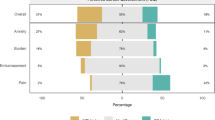

Survey design and reaching a consensus. Initially, 53 terms relating to AS were included in the first-round survey. Subsequently, eight new terms were added to this list by participants in the first round. Thus, the second survey consisted of 61 terms. Terms were classified according to the following themes: background (n = 3), risk groups and surveillance (n = 7), cancer definitions (n = 6), biopsy (n = 13), treatment choice (n = 8), reclassification/progression (n = 13), markers (n = 6) and other AS terms (n = 5). At the end of round two, 64% (n = 39) of the survey items achieved consensus. The majority of the items and their subsequent definitions on which no consensus was reached in the second survey (19 of 22) were discussed in more detail during the consensus meeting. Some items were not discussed owing to time constraints; these terms included localized prostate cancer, indolent tumour and tumour progression. Based on the discussions, some of the terms were excluded from the glossary (Table 3). Reasons for exclusion included unfamiliarity with the concept (n = 2), insufficient evidence to determine the definition of a term (n = 1), or the experts considered them unclear and not useful in the field of AS (n = 9). Based on the results of the second survey and the consensus meeting, a third survey was designed. This final survey consisted of 23 items: definitions on which a consensus was not reached in the second survey and were adapted based on the input of the experts in this survey (n = 5); definitions on which a consensus was not reached in the second survey, which were discussed during the consensus meeting and adapted based on the experts' input (n = 8); and of definitions upon which a consensus was reached in the second survey, but were adapted slightly based on suggestions for improvement from the participants in this second survey (n = 10). Consensus was reached with respect to definitions of all these terms.

Results of the Delphi process. By the end of the Delphi process, formal consensus (≥70% agreement) was achieved on 100% of terms (n = 61). In total, consensus definitions were formulated for 51 terms (Table 1). The additional 10 terms were excluded from the AS glossary, as all experts agreed these terms are unclear and unnecessary in the field of AS (Table 3). Of the 51 terms, 25 definitions reached full consensus (100% agreement). Complete agreement was reached on definitions of key terms such as AS, WW, upgrading and upstaging. For 26 items, consensus ranged from 75% to 92%. Small ambiguities were encountered with definitions related to the various risk groups that are used to stratify patients with prostate cancer (n = 4), cancer definitions (n = 2), biopsy terms (n = 2), treatment choices (n = 4), reclassification/progression (n = 9) and other AS terms (n = 5). Furthermore, a semantic model has been developed, representing an AS timeline (from prostate cancer diagnosis to long-term evaluation of AS), including associated terms and definitions from the glossary (Fig. 3). This overview includes some key terms from the glossary, but is not exhaustive. The first event to occur in this AS timeline is the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Once the diagnosis of prostate cancer is established, further evaluation that incorporates known risk factors is required to determine appropriate treatment options. During AS, the prostate cancer is closely monitored over time. If repeated risk evaluation shows changes in the condition of the patient, treatment plans can be adapted accordingly.

The first event is diagnosis of prostate cancer by biopsy sampling. Patients are then evaluated and stratified by the risk category of their disease: very-low-risk, low-risk, intermediate-risk, high-risk or clinically insignificant. A treatment choice appropriate to their risk category is then made, choices of therapy include AS, watchful waiting, active treatment and definitive treatment. Patients can then undergo re-evaluation diagnostics including a confirmatory biopsy and assessing the Gleason score of the cancer, after which a repeat risk evaluation can be undertaken. Based on this new risk evaluation, treatment can be adapted accordingly and patients enter into a long-term evaluation protocol.

Challenges in achieving a consensus

An urgent need exists for uniform terminology regarding AS in order to aid communication and collaboration among research groups around the world. The purpose of this study was to reach international consensus on definitions of terms often used in AS for carefully selected men with localized, well-differentiated prostate cancer. Using a modified Delphi method in which 12 known leaders in the field participated, agreement has been reached on 61 relevant terms and subsequent definitions relating to AS for prostate cancer.

Several findings deserve particular attention. The experts encountered difficulties regarding the definitions of the various risk groups used to stratify patients with prostate cancer, namely very-low-risk, low-risk, intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer. The explanation for why these difficulties were encountered seems to be multifactorial. Firstly, too many doubts existed on the combinations of clinical criteria — including clinical and pathological characteristics — that differentiate the various risk groups. Many questions were raised by the experts, including whether only clinical stage, serum PSA level and Gleason score should be included; whether other criteria, such as PSA density and maximum percentage of cancer per core biopsy are also pertinent and at what level the cut-off values should be set. Secondly, difficulties were encountered with regard to the cancer-specific survival rates that are associated with these risk groups. Thirdly, the experts had different perspectives on the definition of risk. For example, whether this term refers to the risk of metastasis or cancer-specific mortality. The experts concluded that, at present, the risk groups should not be defined, apart from general concepts, owing to the fact that robust data from men with clinically insignificant prostate cancer who are undergoing AS, especially from studies with >10 years mean follow-up duration, remains limited. The Movember Foundation's GAP3 project, which was launched in August 2014, can make a substantial contribution to the collection of robust data6,14. By combining data from existing AS databases (including clinical, biopsy sample, imaging and biomarker data) from all over the world, the largest centralized prostate cancer AS database to date has been created, which will be updated annually. By subsequently analysing data from the majority of patients who are currently undergoing AS worldwide, appropriate definitions of the various risk groups will likely be delineated.

In addition to concerns regarding definition of the risk groups, intensive and complex discussion occurred on the distinction between the concepts of AS and WW. A formal consensus has been reached on the definitions of both management strategies, but the experts involved indicated that it was difficult to dichotomize surveillance. According to the experts, the intensity of surveillance gradually declines over time. An agreement seems to exist regarding both ends of the spectrum: protocol-based surveillance (that gives rise to curative treatment) at one end and no surveillance at the other end. However, the existence of a grey zone in between these strategies has been acknowledged (Fig. 4). This grey zone was described by the experts as a phase of active (regular) annual monitoring of serum PSA levels (no biopsies undertaken) with the aim of palliation when deemed necessary. Many clinical questions arose, including what this strategy should be called in practice — the terms 'slow surveillance' and 'AS light' were proposed but not agreed upon — or whether it should simply be referred to as 'non-protocol-based surveillance'. Also, the questions of what patients call this type of surveillance and how they perceive it, arose during the consensus procedure. Furthermore, how AS should be practiced was discussed, including aspects such as whether a serum PSA test should be performed every year or, for instance, every 5 years, and what the best strategy for deciding to stop the AS protocol is. Clearly, despite the availability of considerable consensus on the key terminology, continued research is necessary to gain a deeper understanding of these clinical aspects of undertaking and practising AS.

This grey zone was described by the experts as a phase of active (regular) annual monitoring of serum PSA levels (no biopsies undertaken) with the aim of palliation when deemed necessary.

Biopsy sampling and analysis has a role in the risk assessment of patients with prostate cancer who are eligible for AS. After initiation of an AS programme, most guidelines recommend use of surveillance biopsies to check for and identify pathological indications of tumour progression. Many biopsy-related terms were found in the literature and several more were raised by the experts in the survey rounds of our study, including initial biopsy, first biopsy, second biopsy, repeat biopsy, serial biopsy and systematic biopsy. All experts agreed that the majority of these terms are unclear and unnecessary in the field of AS, and, therefore, should not be included in the glossary (Table 3). The experts strongly advise clinicians, researchers and patients to limit the terms to diagnostic biopsy, confirmatory biopsy, protocol-based (surveillance) biopsy and non-protocol-based (surveillance) biopsy to avoid confusion in clinical practice.

Many definitions on which consensus was reached by the panel of experts incorporate references to the Gleason grading and scoring system. A group from Johns Hopkins Hospital led by Dr Epstein first proposed grouping scores into five prognostic categories, termed Grade Groups 1–5 (Ref. 15). A subsequent multi-institutional study of >20,000 men validated these Grade Groups, which resulted in its acceptance by the International Society of Urological Pathology, the WHO and the College of American Pathologists16. Importantly, these new grades are likely to enter mainstream practice in the near future, which will, in turn, potentially influence AS terminology.

Many projects that aim to introduce standard terminology in clinical practice are unsuccessful, perhaps because standard terminology is rarely used in clinical practice7. A number of opportunities exist to consider how to most effectively implement standardized terminology for AS into clinical practice. The aim of the Movember Foundation's GAP3 initiative6,14 is to offer standardized, evidence-based guidelines on AS. The glossary of terms can be added to these guidelines and form the basis for a full understanding of the presented recommendations. Additionally, the homogeneous semantics should be used in presentations at major meetings of national and international associations, and included in papers that will be published in national and international scientific journals and specialists journals.

Strengths and weaknesses

The modified Delphi method seems to have been successful for deriving consensus definitions. Furthermore, the face-to-face consensus meeting of the referee group enabled the in-depth exploration of the reasons for disagreements on definitions. These discussions accelerated the consensus process and revealed new areas of interest (such as the grey area between AS and WW). Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. As purposive sampling was used (and participants were, therefore, not randomly selected), representativeness cannot be assured. However, the whole premise behind the Delphi theory is that the panel members are in fact experts in their field, therefore, yielding results of increased accuracy, instead of selecting a representative sample of the population. Furthermore, the number of experts that participated in this Delphi study (sample size) was relatively small. The number of participants could have affected the potential for ideas as well as the amount of data analysed. However, no agreement on the panel size for Delphi studies exists, and neither do recommendations or unequivocal definitions of small or large samples17. Many published Delphi studies use panels consisting of 10–100 or more panellists17. Official consensus was obtained regarding all 61 definitions, but not all experts fully agreed with all final definitions. Consensus was considered to be reached if ≥70% of the experts agreed on a definition. In the current study, consensus varied between 75% and 100% per item. Also, one term (radiological progression) has been excluded from the AS dictionary because insufficient evidence exists to include it as yet. In a systematic review on the use of MRI in men with low-risk or intermediate-risk prostate cancer who were considered suitable for AS, MRI was demonstrated to be useful for the detection of clinically significant disease at initial clinical assessment of men considering AS18. In addition, MRI might be useful for confirming the absence of any large anterior lesions that could have been missed during routine diagnosis19. However, robust, formally published data are needed before widespread implementation of MRI for this purpose18,20. Most likely, the semantics of AS will need to be augmented with MRI-related definitions as new evidence becomes available. During the course of the GAP3 project, many current patient series have been found to lack sufficient volume to be analysed appropriately. Additional funding has been committed by the Movember Foundation to assess the value of MRI within AS. In conclusion, the findings of this Delphi consensus procedure represent expert opinion, rather than indisputable fact, which should be kept in mind21.

Conclusions

Agreement between international experts has been reached on relevant terms and subsequent definitions regarding AS for patients with localized prostate cancer. This standard terminology could support multidisciplinary communication, reduce the extent of variations in clinical practice and optimize clinical decision making. International debate on all aspects of AS might be strengthened by an improved understanding of the concept of AS.

Change history

30 March 2017

In the original Figure 3 an instance of 'disease' was misspelled. This error has now been corrected.

References

Dall'Era, M. A. et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur. Urol. 62, 976–983 (2012).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. NCCN http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp (2017).

Morash, C. et al. Active surveillance for the management of localized prostate cancer: guideline recommendations. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 9, 171–178 (2015).

Klotz, L. Active surveillance for men with low-risk, clinically localized prostate cancer. UpToDate http://www.uptodate.com/contents/active-surveillance-for-men-with-low-risk-clinically-localized-prostate-cancer (2017).

Ip, S. et al. An evidence review of active surveillance in men with localized prostate cancer. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. (Full Rep.) 204, 1–341 (2011).

Bruinsma, S. M. et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a narrative review of clinical guidelines. Nat. Rev. Urol. 13, 151–167 (2016).

Stallinga, H. A. et al. Does language ambiguity in clinical practice justify the introduction of standard terminology? An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 24, 344–352 (2015).

Kleynen, M. et al. Using a Delphi technique to seek consensus regarding definitions, descriptions and classification of terms related to implicit and explicit forms of motor learning. PLoS ONE 9, e100227 (2014).

Bruinsma, S. M., Bangma, C. H., Obbink, H. & Roobol, M. J. Active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer: the study protocol of the Movember Global Action Plan 3 (GAP3) project [abstract 1036]. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 14, e1036–e1036a (2015).

Yeh, J. S., Van Hoof, T. J. & Fischer, M. A. Key features of academic detailing: development of an expert consensus using the Delphi method. Am. Health Drug Benefits 9, 42–50 (2016).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. Protocol of the COSMIN study: COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 6, 2 (2006).

Zafar, S. Y. et al. Consensus-based standards for best supportive care in clinical trials in advanced cancer. Lancet Oncol. 13, e77–e82 (2012).

Hasson, F., Keeney, S. & McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 32, 1008–1015 (2000).

Bruinsma, S. M. Global action plan on active surveillance for low risk PC: Movember Foundation launches integrated project on active surveillance. Eur. Urol. Today 26, 26 (2014).

Pierorazio, P. M., Walsh, P. C., Partin, A. W. & Epstein, J. I. Prognostic Gleason grade grouping: data based on the modified Gleason scoring system. BJU Int. 111, 753–760 (2013).

Epstein, J. I. et al. A contemporary prostate cancer grading system: a validated alternative to the Gleason score. Eur. Urol. 69, 428–435 (2016).

Akins, R. B., Tolson, H. & Cole, B. R. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 5, 37 (2005).

Schoots, I. G. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in active surveillance of prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur. Urol. 67, 627–636 (2014).

Sankineni, S., Osman, M. & Choyke, P. L. Functional MRI in prostate cancer detection. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 590638 (2014).

Moore, C. M. et al. Reporting MRI in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer — the PRECISE (Prostate Cancer Radiological Estimation of Change in Sequential Evaluation) recommendations: a report of a European School of Oncology task force. Eur. Urol. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.011 (2016).

Powell, C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J. Adv. Nurs. 41, 376–382 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study is linked to a larger project, The Movember Foundation's Global Action Plan Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance (GAP3) initiative, which is a collaboration between institutions, hospitals and research centres from the USA, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Japan, Korea, UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, France, Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Italy and Spain. The Movember Foundation has invested €1,664,950 in GAP3 to create the largest centralized prostate cancer active surveillance database to date. This funder did not have any role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the drafting of this paper. For information, contact M.J.R. m.roobol@erasmusmc.nl.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors researched data for and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission, S.M.B. wrote the article and S.M.B., M.J.R. and C.H.B. provided a substantial contribution to discussions of content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information S1 (table)

Panel of experts (DOC 39 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruinsma, S., Roobol, M., Carroll, P. et al. Semantics in active surveillance for men with localized prostate cancer — results of a modified Delphi consensus procedure. Nat Rev Urol 14, 312–322 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2017.26

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2017.26

This article is cited by

-

Expanding the role of PSMA PET in active surveillance

BMC Urology (2023)

-

A prospective cohort study on active surveillance after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer: protocol of Surgery As Needed for Oesophageal cancer-2

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Oncological results and cancer control definition in focal therapy for Prostate Cancer: a systematic review

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2023)

-

MXene-assisted organic electrochemical transistor biosensor with multiple spiral interdigitated electrodes for sensitive quantification of fPSA/tPSA

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2021)

-

Considering the role of radical prostatectomy in 21st century prostate cancer care

Nature Reviews Urology (2020)