Key Points

-

Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) bind specifically to osteoclasts and osteoclast precursors in the normal bone and joint compartment; such binding promotes osteoclast differentiation and osteolytic function in vitro

-

Osteoclast differentiation is dependent on the citrullination of proteins by protein-arginine deiminases

-

Both Fc-dependent and Fc-independent mechanisms are involved in ACPA-mediated osteoclast activation

-

Binding of ACPAs to osteoclasts induces the production of the chemokine IL-8

-

Infusion of ACPAs into mice causes IL-8-dependent bone loss and IL-8-mediated pain behaviour

-

The unique role of citrullination in osteoclast differentiation and ACPA-induced osteoclast activation might explain important features of the gradual development of rheumatoid arthritis, including why the joints are targeted

Abstract

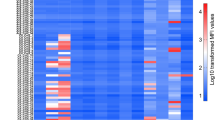

A key unanswered question in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is how systemic autoimmunity progresses to joint-specific inflammation. In patients with seropositive RA (that is, characterized by the presence of autoantibodies) evidence is accumulating that immunity against post-translationally modified (such as citrullinated) autoantigens might be triggered in mucosal organs, such as the lung, long before the first signs of inflammation are seen in the joints. However, the mechanism by which systemic autoimmunity specifically homes to the joint and bone compartment, thereby triggering inflammation, remains elusive. This Review summarizes potential pathways involved in this joint-homing mechanism, focusing particularly on osteoclasts as the primary targets of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) in the bone and joint compartment. Osteoclasts are dependent on citrullinating enzymes for their normal differentiation and are unique in displaying citrullinated antigens on their cell surface in a non-inflamed state. The binding of ACPAs to osteoclasts releases the chemokine IL-8, leading to bone erosion and pain. This process initiates a chain of events that could lead to attraction and activation of neutrophils, resulting in a complex series of proinflammatory processes in the synovium, eventually leading to RA.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Klareskog, L., Catrina, A. I. & Paget, S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 373, 659–672 (2009).

Nielen, M. M. et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 380–386 (2004).

Rantapaa-Dahlqvist, S. et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 2741–2749 (2003).

Brink, M. et al. Multiplex analyses of antibodies against citrullinated peptides in individuals prior to development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 65, 899–910 (2013).

Chibnik, L. B., Mandl, L. A., Costenbader, K. H., Schur, P. H. & Karlson, E. W. Comparison of threshold cutpoints and continuous measures of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in predicting future rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 36, 706–711 (2009).

Koppejan, H. et al. Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis, first-degree relatives and controls: comparison to anti-citrullinated protein antibodies. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 2090–2098 (2016).

Brink, M. et al. Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies in the pre-symptomatic phase of rheumatoid arthritis, their relationship with multiple anti-citrulline peptide antibodies and association with radiological damage. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 25 (2015).

Shi, J. et al. Anti-carbamylated protein (anti-CarP) antibodies precede the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 780–783 (2014).

Sokolove, J. et al. Autoantibody epitope spreading in the pre-clinical phase predicts progression to rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE 7, e35296 (2012).

Catrina, A. I., Ytterberg, A. J., Reynisdottir, G., Malmstrom, V. & Klareskog, L. Lungs, joints and immunity against citrullinated proteins in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10, 645–653 (2014).

Chatzidionisyou, A. & Catrina, A. I. The lung in rheumatoid arthritis, cause or consequence? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 28, 76–82 (2016).

Catrina, A. I., Deane, K. D. & Scher, J. U. Gene, environment, microbiome and mucosal immune tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 55, 391–402 (2016).

Leech, M. T. & Bartold, P. M. The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 29, 189–201 (2015).

Koziel, J., Mydel, P. & Potempa, J. The link between periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis: an updated review. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 16, 408 (2014).

Payne, J. B., Golub, L. M., Thiele, G. M. & Mikuls, T. R. The Link Between Periodontitis and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Periodontist's Perspective. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2, 20–29 (2015).

Aho, K., Heliovaara, M., Maatela, J., Tuomi, T. & Palosuo, T. Rheumatoid factors antedating clinical rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 18, 1282–1284 (1991).

Kurki, P., Aho, K., Palosuo, T. & Heliovaara, M. Immunopathology of rheumatoid arthritis. Antikeratin antibodies precede the clinical disease. Arthritis Rheum. 35, 914–917 (1992).

Haj Hensvold, A. et al. Environmental and genetic factors in the development of anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) and ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis: an epidemiological investigation in twins. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 375–380 (2013).

van der Woude, D. et al. Epitope spreading of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody response occurs before disease onset and is associated with the disease course of early arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1554–1561 (2010).

van de Stadt, L. A. et al. Development of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody repertoire prior to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 3226–3233 (2011).

Juarez, M. et al. Identification of novel antiacetylated vimentin antibodies in patients with early inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1099–1107 (2016).

Mathsson, L. et al. Antibodies against citrullinated vimentin in rheumatoid arthritis: higher sensitivity and extended prognostic value concerning future radiographic progression as compared with antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 36–45 (2008).

Kastbom, A. et al. Changes in the anticitrullinated peptide antibody response in relation to therapeutic outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the SWEFOT trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 356–361 (2016).

Hensvold, A. H. et al. Serum RANKL levels associate with anti- citrullinated protein antibodies in early untreated rheumatoid arthritis and are modulated following methotrexate. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 239 (2015).

Bos, W. H. et al. Arthritis development in patients with arthralgia is strongly associated with anti-citrullinated protein antibody status: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 490–494 (2010).

Stack, R. J. et al. Symptom complexes in patients with seropositive arthralgia and in patients newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative exploration of symptom development. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53, 1646–1653 (2014).

Neovius, M., Simard, J. F., Askling, J. & Group, A. S. How large are the productivity losses in contemporary patients with RA, and how soon in relation to diagnosis do they develop? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 1010–1015 (2011).

Innala, L. et al. Antibodies against mutated citrullinated vimentin are a better predictor of disease activity at 24 months in early rheumatoid arthritis than antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides. J. Rheumatol. 35, 1002–1008 (2008).

Mustila, A. et al. Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies and the progression of radiographic joint erosions in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with FIN-RACo combination and single disease-modifying antirheumatic drug strategies. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 29, 500–505 (2011).

Syversen, S. W. et al. Prediction of radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis and the role of antibodies against mutated citrullinated vimentin: results from a 10-year prospective study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 345–351 (2010).

van Steenbergen, H. W., Ajeganova, S., Forslind, K., Svensson, B. & van der Helm-van Mil, A. H. The effects of rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibodies on bone erosions in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, e3 (2015).

Hecht, C. et al. Additive effect of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and rheumatoid factor on bone erosions in patients with RA. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 2151–2156 (2015).

Shi, J. et al. Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17372–17377 (2011).

Kleyer, A. et al. Bone loss before the clinical onset of rheumatoid arthritis in subjects with anticitrullinated protein antibodies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 854–860 (2013).

van Schaardenburg, D. et al. Bone metabolism is altered in preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 1173–1174 (2011).

Harre, U. et al. Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1791–1802 (2012).

Ossipova, E. et al. Affinity purified anti-citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies target antigens expressed in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, R167 (2014).

Krishnamurthy, A. et al. Identification of a novel chemokine-dependent molecular mechanism underlying rheumatoid arthritis-associated autoantibody-mediated bone loss. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 721–729 (2016).

Du, N. et al. Cell surface vimentin is an attachment receptor for enterovirus 71. J. Virol. 88, 5816–5833 (2014).

Amara, K. et al. Monoclonal IgG antibodies generated from joint-derived B cells of RA patients have a strong bias toward citrullinated autoantigen recognition. J. Exp. Med. 210, 445–455 (2013).

Negishi-Koga, T. et al. Immune complexes regulate bone metabolism through FcRgamma signalling. Nat. Commun. 6, 6637 (2015).

Harre, U. et al. Glycosylation of immunoglobulin G determines osteoclast differentiation and bone loss. Nat. Commun. 6, 6651 (2015).

Rombouts, Y. et al. Extensive glycosylation of ACPA-IgG variable domains modulates binding to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 578–585 (2016).

Wigerblad, G. et al. Autoantibodies to citrullinated proteins induce joint pain independent of inflammation via a chemokine-dependent mechanism. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 730–738 (2016).

Moscarello, M. A., Wood, D. D., Ackerley, C. & Boulias, C. Myelin in multiple sclerosis is developmentally immature. J. Clin. Invest. 94, 146–154 (1994).

Beniac, D. R. et al. Cryoelectron microscopy of protein-lipid complexes of human myelin basic protein charge isomers differing in degree of citrullination. J. Struct. Biol. 129, 80–95 (2000).

Senshu, T., Kan, S., Ogawa, H., Manabe, M. & Asaga, H. Preferential deimination of keratin K1 and filaggrin during the terminal differentiation of human epidermis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 225, 712–719 (1996).

Senshu, T., Akiyama, K. & Nomura, K. Identification of citrulline residues in the V subdomains of keratin K1 derived from the cornified layer of newborn mouse epidermis. Exp. Dermatol. 8, 392–401 (1999).

Harding, C. R. & Scott, I. R. Histidine-rich proteins (filaggrins): structural and functional heterogeneity during epidermal differentiation. J. Mol. Biol. 170, 651–673 (1983).

Pearton, D. J., Dale, B. A. & Presland, R. B. Functional analysis of the profilaggrin N-terminal peptide: identification of domains that regulate nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution. J. Invest. Dermatol. 119, 661–669 (2002).

Scott, I. R., Harding, C. R. & Barrett, J. G. Histidine-rich protein of the keratohyalin granules. Source of the free amino acids, urocanic acid and pyrrolidone carboxylic acid in the stratum corneum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 719, 110–117 (1982).

Makrygiannakis, D. et al. Citrullination is an inflammation-dependent process. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, 1219–1222 (2006).

Rothe, L. et al. Human osteoclasts and osteoclast-like cells synthesize and release high basal and inflammatory stimulated levels of the potent chemokine interleukin-8. Endocrinology 139, 4353–4363 (1998).

Kopesky, P. et al. Autocrine signaling is a key regulatory element during osteoclastogenesis. Biol. Open 3, 767–776 (2014).

van Steenbergen, H. W., Mangnus, L., Reijnierse, M., Huizinga, T. W. & van der Helm-van Mil, A. H. Clinical factors, anticitrullinated peptide antibodies and MRI-detected subclinical inflammation in relation to progression from clinically suspect arthralgia to arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1824–1830 (2016).

van de Stadt, L. A. et al. The extent of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody repertoire is associated with arthritis development in patients with seropositive arthralgia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 128–133 (2011).

Nam, J. L., Hunt, L., Hensor, E. M. & Emery, P. Enriching case selection for imminent RA: the use of anti-CCP antibodies in individuals with new non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms - a cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1452–1456 (2016).

Rakieh, C. et al. Predicting the development of clinical arthritis in anti-CCP positive individuals with non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1659–1666 (2015).

Andoh, T. & Kuraishi, Y. Direct action of immunoglobulin G on primary sensory neurons through Fc gamma receptor I. FASEB J. 18, 182–184 (2004).

Qu, L., Zhang, P., LaMotte, R. H. & Ma, C. Neuronal Fc-gamma receptor I mediated excitatory effects of IgG immune complex on rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 1399–1407 (2011).

Cunha, T. M. et al. A cascade of cytokines mediates mechanical inflammatory hypernociception in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 1755–1760 (2005).

Guerrero, A. T. et al. Toll-like receptor 2/MyD88 signaling mediates zymosan-induced joint hypernociception in mice: participation of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and CXCL1/KC. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 674, 51–57 (2012).

Qin, X., Wan, Y. & Wang, X. CCL2 and CXCL1 trigger calcitonin gene-related peptide release by exciting primary nociceptive neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 82, 51–62 (2005).

Zhang, Z. J., Cao, D. L., Zhang, X., Ji, R. R. & Gao, Y. J. Chemokine contribution to neuropathic pain: respective induction of CXCL1 and CXCR2 in spinal cord astrocytes and neurons. Pain 154, 2185–2197 (2013).

Wang, J. G. et al. The chemokine CXCL1/growth related oncogene increases sodium currents and neuronal excitability in small diameter sensory neurons. Mol. Pain 4, 38 (2008).

Kuhn, K. A. et al. Antibodies against citrullinated proteins enhance tissue injury in experimental autoimmune arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 961–973 (2006).

Sohn, D. H. et al. Local Joint inflammation and histone citrullination in a murine model of the transition from preclinical autoimmunity to inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 2877–2887 (2015).

Marinova-Mutafchieva, L., Williams, R. O., Funa, K., Maini, R. N. & Zvaifler, N. J. Inflammation is preceded by tumor necrosis factor-dependent infiltration of mesenchymal cells in experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 507–513 (2002).

Hetland, M. L. et al. MRI bone oedema is the strongest predictor of subsequent radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Results from a 2-year randomised controlled trial (CIMESTRA). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 384–390 (2009).

Haavardsholm, E. A., Boyesen, P., Ostergaard, M., Schildvold, A. & Kvien, T. K. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in 84 patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: bone marrow oedema predicts erosive progression. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 794–800 (2008).

Boyesen, P. et al. Prediction of MRI erosive progression: a comparison of modern imaging modalities in early rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 176–179 (2011).

McQueen, F. M. et al. Bone edema scored on magnetic resonance imaging scans of the dominant carpus at presentation predicts radiographic joint damage of the hands and feet six years later in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 1814–1827 (2003).

Sokolove, J., Zhao, X., Chandra, P. E. & Robinson, W. H. Immune complexes containing citrullinated fibrinogen costimulate macrophages via Toll-like receptor 4 and Fcgamma receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 53–62 (2011).

Trouw, L. A. et al. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies from rheumatoid arthritis patients activate complement via both the classical and alternative pathways. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 1923–1931 (2009).

Khandpur, R. et al. NETs are a source of citrullinated autoantigens and stimulate inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 178ra40 (2013).

Suurmond, J. et al. Toll-like receptor triggering augments activation of human mast cells by anti-citrullinated protein antibodies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1915–1923 (2015).

Habets, K. L. et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies contribute to platelet activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 209 (2015).

Lu, M. C. et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies promote apoptosis of mature human Saos-2 osteoblasts via cell-surface binding to citrullinated heat shock protein 60. Immunobiology 221, 76–83 (2016).

Barbarroja, N. et al. Anticyclic citrullinated protein antibodies are implicated in the development of cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arterioscler, Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 2706–2716 (2014).

Makrygiannakis, D. et al. Local administration of glucocorticoids decreases synovial citrullination in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14, R20 (2012).

Makrygiannakis, D. et al. Smoking increases peptidylarginine deiminase 2 enzyme expression in human lungs and increases citrullination in BAL cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 1488–1492 (2008).

Lugli, E. B. et al. Expression of citrulline and homocitrulline residues in the lungs of non-smokers and smokers: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 9 (2015).

Nesse, W. et al. The periodontium of periodontitis patients contains citrullinated proteins which may play a role in ACPA (anti-citrullinated protein antibody) formation. J. Clin. Periodontol 39, 599–607 (2012).

Bongartz, T. et al. Citrullination in extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46, 70–75 (2007).

McInnes, I. B., Buckley, C. D. & Isaacs, J. D. Cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis - shaping the immunological landscape. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 63–68 (2016).

Feldmann, M. & Maini, S. R. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: an education in pathophysiology and therapeutics. Immunol. Rev. 223, 7–19 (2008).

Patel, R., Filer, A., Barone, F. & Buckley, C. D. Stroma: fertile soil for inflammation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 28, 565–576 (2014).

Bartok, B. & Firestein, G. S. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol. Rev. 233, 233–255 (2010).

Chemin, K., Klareskog, L. & Malmstrom, V. Is rheumatoid arthritis an autoimmune disease? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 28, 181–188 (2016).

James, E. A. et al. Citrulline-specific Th1 cells are increased in rheumatoid arthritis and their frequency is influenced by disease duration and therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 1712–1722 (2014).

Reparon-Schuijt, C. C. et al. Secretion of anti-citrulline-containing peptide antibody by B lymphocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 41–47 (2001).

Nandakumar, K. S. Pathogenic antibody recognition of cartilage. Cell Tissue Res. 339, 213–220 (2010).

Cook, A. D., Rowley, M. J., Mackay, I. R., Gough, A. & Emery, P. Antibodies to type II collagen in early rheumatoid arthritis. Correlation with disease progression. Arthritis Rheum. 39, 1720–1727 (1996).

Lindh, I. et al. Type II collagen antibody response is enriched in the synovial fluid of rheumatoid joints and directed to the same major epitopes as in collagen induced arthritis in primates and mice. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, R143 (2014).

Ronnelid, J., Lysholm, J., Engstrom-Laurent, A., Klareskog, L. & Heyman, B. Local anti-type II collagen antibody production in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid. Evidence for an HLA-DR4-restricted IgG response. Arthritis Rheum. 37, 1023–1029 (1994).

Haag, S. et al. Identification of new citrulline-specific autoantibodies, which bind to human arthritic cartilage, by mass spectrometric analysis of citrullinated type II collagen. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66, 1440–1449 (2014).

Turunen, S., Hannonen, P., Koivula, M. K., Risteli, L. & Risteli, J. Separate and overlapping specificities in rheumatoid arthritis antibodies binding to citrulline- and homocitrulline-containing peptides related to type I and II collagen telopeptides. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 2 (2015).

Lundberg, K. et al. Genetic and environmental determinants for disease risk in subsets of rheumatoid arthritis defined by the anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody fine specificity profile. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 652–658 (2013).

Ditzel, H. J. The K/BxN mouse: a model of human inflammatory arthritis. Trends Mol. Med. 10, 40–45 (2004).

Reynisdottir, G. et al. Signs of immune activation and local inflammation are present in the bronchial tissue of patients with untreated early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1722–1727 (2016).

Nesse, W. et al. The periodontium of periodontitis patients contains citrullinated proteins which may play a role in ACPA (anti-citrullinated protein antibody) formation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 39, 599–607 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors' research is supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council; the European Union 7th Framework Programme (FP7) project FP7-HEALTH-2012 INNOVATION-1 Euro-TEAM (305549–2); the Initial Training Network 7th Framework Osteoimmune Programme (289150); the Innovative Medicine Initiative, Be The Cure (115142–2); and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (all to A.I.C. and L.K.); and from the German Research Council Priority Programme, SPP 1468 - Immunobone (CRC1181) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) project METARTHROS (to G.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors researched data for the article, contributed substantially to discussions of its content and wrote the manuscript. A.I.C. and L.K. contributed equally to review and/or editing of the article before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Catrina, A., Svensson, C., Malmström, V. et al. Mechanisms leading from systemic autoimmunity to joint-specific disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 13, 79–86 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.200

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2016.200

This article is cited by

-

Comparative risk of infections between JAK inhibitors versus TNF inhibitors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort study

Arthritis Research & Therapy (2023)

-

Lymphocyte activation gene 3 is increased and affects cytokine production in rheumatoid arthritis

Arthritis Research & Therapy (2023)

-

Neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases

Nature Reviews Immunology (2023)

-

Modulation of B cell activation by extracellular vesicles and potential alteration of this pathway in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Arthritis Research & Therapy (2022)

-

Passive smoking in childhood accelerates RA risk for smokers

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2022)