Key Points

-

Ablative therapy and autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) is an increasingly studied and used strategy for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS)

-

AHSCT confers benefits for patients with MS by achieving radical suppression of inflammatory MS activity

-

Qualitative changes in the reconstituted immune system and durable remissions without additional immune intervention support the notion that AHSCT regenerates the immune system (a process known as immune resetting)

-

Complete suppression of MS disease activity for 4–5 years has been documented in 70–80% of patients with relapsing–remitting MS who have undergone AHSCT; neurological improvements have also been demonstrated

-

Optimal candidates for AHSCT are young, ambulatory and have inflammatory-active relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS); current appropriate indications for AHSCT include aggressive and highly active treatment-refractory RRMS

-

Clinical trials to compare AHSCT with approved drugs in RRMS and determine its benefits in inflammatory-active progressive MS are warranted, but progress is hindered by a lack of investment and funding

Abstract

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) is a multistep procedure that enables destruction of the immune system and its reconstitution from haematopoietic stem cells. Originally developed for the treatment of haematological malignancies, the procedure has been adapted for the treatment of severe immune-mediated disorders. Results from ∼20 years of research make a compelling case for selective use of AHSCT in patients with highly active multiple sclerosis (MS), and for controlled trials. Immunological studies support the notion that AHSCT causes qualitative immune resetting, and have provided insight into the mechanisms that might underlie the powerful treatment effects that last well beyond recovery of immune cell numbers. Indeed, studies have demonstrated that AHSCT can entirely suppress MS disease activity for 4–5 years in 70–80% of patients, a rate that is higher than those achieved with any other therapies for MS. Treatment-related mortality, which was 3.6% in studies before 2005, has decreased to 0.3% in studies since 2005. Current evidence indicates that the patients who are most likely to benefit from and tolerate AHSCT are young, ambulatory and have inflammatory MS activity. Clinical trials are required to rigorously test the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of AHSCT against highly active MS drugs.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fassas, A. et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in the treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis: first results of a pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 20, 631–638 (1997).

Mancardi, G. L. et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation suppresses Gd-enhanced MRI activity in MS. Neurology 57, 62–68 (2001).

Saiz, A. et al. Clinical and MRI outcome after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in MS. Neurology 62, 282–284 (2004).

Burt, R. K. et al. Autologous non-myeloablative haemopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase I/II study. Lancet Neurol. 8, 244–253 (2009).

Muraro, P. A. et al. Thymic output generates a new and diverse TCR repertoire after autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis patients. J. Exp. Med. 201, 805–816 (2005). First demonstration of so-called immune resetting; a new and more diverse T cell repertoire is regenerated following thymus reactivation post-transplantation, leading to increase of naive T cells.

Abrahamsson, S. V. et al. Non-myeloablative autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation expands regulatory cells and depletes IL-17 producing mucosal-associated invariant T cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain 136, 2888–2903 (2013). Non-myeloablative AHSCT causes a radical and sustained depletion in circulating MAIT cells, which are implicated in MS pathophysiology by their presence in MS post-mortem CNS lesions, and a surge in regulatory T and NK cells early after transplantation.

Darlington, P. J. et al. Diminished Th17 (not Th1) responses underlie multiple sclerosis disease abrogation after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann. Neurol. 73, 341–354 (2013). Study of T cells from successfully treated patients demonstrated that they have a reduced proinflammatory interleukin-17 response after transplantation.

Muraro, P. A. et al. T cell repertoire following autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1168–1172 (2014). Deep sequencing analysis of T cell receptor repertoire was used to demonstrate extensive replacement of pre-existing repertoire with new T cell clones emerging post-transplantation, and a greater diversity of repertoire in patients with complete clinical response in the HALT-MS trial.

Nash, R. A. et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (HALT-MS): a 3-year interim report. JAMA Neurol. 72, 159–169 (2015).

Burman, J. et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for aggressive multiple sclerosis: the Swedish experience. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 85, 1116–1121 (2014).

Burt, R. K. et al. Association of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with neurological disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA 313, 275–284 (2015). Largest single-centre study of non-myeloablative AHSCT for treatment of MS and demonstration of neurological improvements after therapy.

Mancardi, G. L. et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a phase II trial. Neurology 84, 981–988 (2015).

Atkins, H. L. et al. Immunoablation and autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for aggressive multiple sclerosis: a multicentre single-group phase 2 trial. Lancet 388, 576–585 (2016). Trial of AHSCT using a high-intensity conditioning regimen with busulfan that demonstrated complete suppression of relapses and MRI inflammatory activity in RRMS and SPMS patients during up to 12.7 years of follow-up after transplantation.

Nash, R. A. et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous HCT for relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology 88, 842–852 (2017). Multi-centre phase II clinical trial of AHSCT in patients with aggressive, treatment-resistant RRMS that demonstrated no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) in ∼70% of patients at 5 years after transplantation

Olesen, J. et al. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 19, 155–162 (2012).

Sormani, M. P. & Bruzzi, P. MRI lesions as a surrogate for relapses in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Neurol. 12, 669–676 (2013).

Appelbaum, F. R. Hematopoietic-cell transplantation at 50. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1472–1475 (2007).

Hinterberger, W., Hinterberger-Fischer, M. & Marmont, A. Clinically demonstrable anti-autoimmunity mediated by allogeneic immune cells favorably affects outcome after stem cell transplantation in human autoimmune diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 30, 753–759 (2002).

Griffith, L. M. et al. Feasibility of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune disease: position statement from a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Cancer Institute-Sponsored International Workshop, Bethesda, MD, March 12 and 13, 2005. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 11, 862–870 (2005).

Saccardi, R. & Gualandi, F. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation procedures. Autoimmunity 41, 570–576 (2008).

Sawcer, S., Franklin, R. J. & Ban, M. Multiple sclerosis genetics. Lancet Neurol. 13, 700–709 (2014).

DeLorenze, G. N. et al. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis: evidence of association from a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Arch. Neurol. 63, 839–844 (2006).

Mokry, L. E. et al. Vitamin D and risk of multiple sclerosis: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 12, e1001866 (2015).

Riise, T., Nortvedt, M. W. & Ascherio, A. Smoking is a risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Neurology 61, 1122–1124 (2003).

Mokry, L. E. et al. Obesity and multiple sclerosis: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 13, e1002053 (2016).

Lucchinetti, C., Bruck, F., Rodriguez, M. & Lassmann, H. Distinct patterns of multiple sclerosis pathology indicates heterogeneity in pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 6, 259–274 (1996).

Planas, R. et al. Central role of Th2/Tc2 lymphocytes in pattern II multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 2, 875–893 (2015).

Sospedra, M. & Martin, R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Semin. Neurol. 36, 115–127 (2016).

Dendrou, C. A., Fugger, L. & Friese, M. A. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 545–558 (2015).

Saccardi, R. et al. Autologous HSCT for severe progressive multiple sclerosis in a multicenter trial: impact on disease activity and quality of life. Blood 105, 2601–2607 (2005).

Burt, R. K. et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for progressive multiple sclerosis: failure of a total body irradiation-based conditioning regimen to prevent disease progression in patients with high disability scores. Blood 102, 2373–2378 (2003).

Nash, R. A. et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for severe multiple sclerosis. Blood 102, 2364–2372 (2003).

Carreras, E. et al. CD34+ selected autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: report of toxicity and treatment results at one year of follow-up in 15 patients. Haematologica 88, 306–314 (2003).

Koehne, G., Zeller, W., Stockschlaeder, M. & Zander, A. R. Phenotype of lymphocyte subsets after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 19, 149–156 (1997).

Sun, W. et al. Characteristics of T-cell receptor repertoire and myelin-reactive T cells reconstituted from autologous haematopoietic stem-cell grafts in multiple sclerosis. Brain 127, 996–1008 (2004).

Muraro, P. A., Pette, M., Bielekova, B., McFarland, H. F. & Martin, R. Human autoreactive CD4+ T cells from naive CD45RA+ and memory CD45RO+ subsets differ with respect to epitope specificity and functional antigen avidity. J. Immunol. 164, 5474–5481 (2000).

Delemarre, E. M. et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation aids autoimmune patients by functional renewal and TCR diversification of regulatory T cells. Blood 127, 91–101 (2016).

Arruda, L. C. et al. Autologous hematopoietic SCT normalizes miR-16, -155 and -142-3p expression in multiple sclerosis patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 50, 380–389 (2015).

Hiepe, F. et al. Long-lived autoreactive plasma cells drive persistent autoimmune inflammation. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7, 170–178 (2011).

Bomberger, C. et al. Lymphoid reconstitution after autologous PBSC transplantation with FACS-sorted CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. Blood 91, 2588–2600 (1998).

Alexander, T. et al. Depletion of autoreactive immunologic memory followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with refractory SLE induces long-term remission through de novo generation of a juvenile and tolerant immune system. Blood 113, 214–223 (2009).

Gokmen, E., Raaphorst, F. M., Boldt, D. H. & Teale, J. M. Ig heavy chain third complementarity determining regions (H CDR3s) after stem cell transplantation do not resemble the developing human fetal H CDR3s in size distribution and Ig gene utilization. Blood 92, 2802–2814 (1998).

Mondria, T., Lamers, C. H., te Boekhorst, P. A., Gratama, J. W. & Hintzen, R. Q. Bone-marrow transplantation fails to halt intrathecal lymphocyte activation in multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 79, 1013–1015 (2008).

de Paula, A. S. A. et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation reduces abnormalities in the expression of immune genes in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Sci. 128, 111–120 (2015). Gene expression analysis by microarray demonstrated a relative normalization of gene expression profiles 2 years after AHSCT in CD8+ and, to a lesser extent, CD4+ cells from patients with MS.

Keller, A. et al. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA profiles in multiple sclerosis including next- generation sequencing. Mult. Scler. 20, 295–303 (2013).

Paraboschi, E. M. et al. Genetic association and altered gene expression of mir-155 in multiple sclerosis patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 8695–8712 (2011).

Waschbisch, A. et al. Glatiramer acetate treatment normalizes deregulated microRNA expression in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 6, e24604 (2011).

Lutterotti, A. et al. No proinflammatory signature in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. 18, 1188–1192 (2012).

Mancardi, G. L. et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation as rescue therapy in malignant forms of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 11, 367–371 (2005).

Fagius, J., Lundgren, J. & Oberg, G. Early highly aggressive MS successfully treated by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Mult. Scler. 15, 229–237 (2009).

Fassas, A. et al. Long-term results of stem cell transplantation for MS: a single-center experience. Neurology 76, 1066–1070 (2011).

Bowen, J. D. et al. Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation following high-dose immunosuppressive therapy for advanced multiple sclerosis: long-term results. Bone Marrow Transplant. 47, 946–951 (2012).

Hamerschlak, N. et al. Brazilian experience with two conditioning regimens in patients with multiple sclerosis: BEAM/horse ATG and CY/rabbit ATG. Bone Marrow Transplant. 45, 239–248 (2010).

Samijn, J. P. et al. Intense T cell depletion followed by autologous bone marrow transplantation for severe multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 77, 46–50 (2006).

Muraro, P. A. et al. Long-term outcomes after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 74, 459–469 (2017). Largest long-term study of outcomes after AHSCT in patients with MS (all subtypes); identified key demographic, disease-related and treatment-related factors associated with progression-free survival and overall survival.

Curro, D. et al. Low intensity lympho-ablative regimen followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe forms of multiple sclerosis: a MRI-based clinical study. Mult. Scler. 21, 1423–1430 (2015).

Giovannoni, G. et al. Is it time to target no evident disease activity (NEDA) in multiple sclerosis? Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 4, 329–333 (2015).

Sormani, M. P., Muraro, P. A., Saccardi, R. & Mancardi, G. NEDA status in highly active MS can be more easily obtained with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation than other drugs. Mult. Scler. 23, 201–204 (2017).

Sormani, M. P. & Muraro, P. Updated views on autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 16, 469–470 (2016).

Coles, A. J. et al. Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 380, 1829–1839 (2012).

Saccardi, R. et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for progressive multiple sclerosis: update of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation autoimmune diseases working party database. Mult. Scler. 12, 814–823 (2006).

Bacigalupo, A. et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 15, 1628–1633 (2009).

Snowden, J. A. et al. Haematopoietic SCT in severe autoimmune diseases: updated guidelines of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 47, 770–790 (2012).

Sormani, M. et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Neurology http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003987 (2017). Largest meta-analysis to date, using meta-regression analysis to identify factors associated with outcomes; reported a substantial decrease in treatment-related mortality in studies since 2005.

Openshaw, H. et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis with busulfan and cyclophosphamide conditioning: report of toxicity and immunological monitoring. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 6, 563–575 (2000).

Euler, H. H. et al. Early recurrence or persistence of autoimmune diseases after unmanipulated autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood 88, 3621–3625 (1996).

Reston, J. T., Uhl, S., Treadwell, J. R., Nash, R. A. & Schoelles, K. Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult. Scler. 17, 204–213 (2011).

Nash, R. A. et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder after high-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous CD34-selected hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe autoimmune diseases. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 9, 583–591 (2003).

Chen, B. et al. Long-term efficacy of autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis at a single institution in China. Neurol. Sci. 33, 881–886 (2012).

Xu, J. et al. Clinical outcome of autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in opticospinal and conventional forms of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis in a Chinese population. Ann. Hematol. 90, 343–348 (2011).

Shevchenko, J. L. et al. Long-term outcomes of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in multiple sclerosis: physician's and patient's perspectives. Ann. Hematol. 94, 1149–1157 (2015).

Maciejewska, M., Snarski, E. & Wiktor-Jedrzejczak, W. A preliminary online study on menstruation recovery in women after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant for autoimmune diseases. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 14, 665–669 (2016).

Snarski, E. et al. Onset and outcome of pregnancy after autologous haematopoietic SCT (AHSCT) for autoimmune diseases: a retrospective study of the EBMT autoimmune diseases working party (ADWP). Bone Marrow Transplant. 50, 216–220 (2015).

Atkins, H. & Freedman, M. Immune ablation followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of poor prognosis multiple sclerosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 549, 231–246 (2009).

Daikeler, T. et al. Secondary autoimmune diseases occurring after HSCT for an autoimmune disease: a retrospective study of the EBMT Autoimmune Disease Working Party. Blood 118, 1693–1698 (2011).

Daikeler, T., Tichelli, A. & Passweg, J. Complications of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with autoimmune diseases. Pediatr. Res. 71, 439–444 (2012).

Mancardi, G. & Saccardi, R. Autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 7, 626–636 (2008).

Coles, A. J. et al. The window of therapeutic opportunity in multiple sclerosis: evidence from monoclonal antibody therapy. J. Neurol. 27, 27 (2005).

Mancardi, G. L. et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation with an intermediate intensity conditioning regimen in multiple sclerosis: the Italian multi-centre experience. Mult. Scler. 18, 835–842 (2012).

Lublin, F. D. New multiple sclerosis phenotypic classification. Eur. Neurol. 72 (Suppl. 1), 1–5 (2014).

Hauser, S. L. et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 676–688 (2008).

Sorensen, P. S. & Blinkenberg, M. The potential role for ocrelizumab in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: current evidence and future prospects. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 9, 44–52 (2016).

Scalfari, A. et al. The relationship of age with the clinical phenotype in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 22, 1750–1758 (2016).

Scalfari, A., Neuhaus, A., Daumer, M., Ebers, G. C. & Muraro, P. A. Age and disability accumulation in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 77, 1246–1252 (2011).

Martinez, C. et al. Comorbidities, not age, are predictive of survival after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma in patients older than 50 years. Ann. Hematol. 96, 9–16 (2017).

Marrie, R. A. et al. Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 85, 240–247 (2015).

Portaccio, E. et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for very active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: report of two cases. Mult. Scler. 13, 676–678 (2007).

Kimiskidis, V. K. et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation in malignant multiple sclerosis: a case with a favorable long-term outcome. Mult. Scler. 14, 278–283 (2008).

Comi, G., Radaelli, M. & Soelberg Sorensen, P. Evolving concepts in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet 389, 1347–1356 (2017).

Rush, C. A., MacLean, H. J. & Freedman, M. S. Aggressive multiple sclerosis: proposed definition and treatment algorithm. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 379–389 (2015).

Scolding, N. et al. Association of British Neurologists: revised (2015) guidelines for prescribing disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. Pract. Neurol. 15, 273–279 (2015).

Dubinsky, A. N., Burt, R. K., Martin, R. & Muraro, P. A. T-cell clones persisting in the circulation after autologous hematopoietic SCT are undetectable in the peripheral CD34+ selected graft. Bone Marrow Transplant. 45, 325–331 (2009).

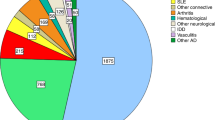

Farge, D. et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: an observational study on 12 years' experience from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Working Party on Autoimmune Diseases. Haematologica 95, 284–292 (2010).

Moore, J. et al. A pilot randomized trial comparing CD34-selected versus unmanipulated hemopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe, refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 2301–2309 (2002).

Oliveira, M. C. et al. Does ex vivo CD34+ positive selection influence outcome after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in systemic sclerosis patients? Bone Marrow Transplant. 51, 501–505 (2016).

Fassas, A. et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in progressive multiple sclerosis — an interim analysis of efficacy. J. Clin. Immunol. 20, 24–30 (2000).

O'Shea, D. et al. Predictive factors for survival in myeloma patients who undergo autologous stem cell transplantation: a single-centre experience in 211 patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 37, 731–737 (2006).

Blystad, A. K. et al. Infused CD34 cell dose, but not tumour cell content of peripheral blood progenitor cell grafts, predicts clinical outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma grade 3 treated with high-dose therapy. Br. J. Haematol. 125, 605–612 (2004).

Bolwell, B. J. et al. Patients mobilizing large numbers of CD34+ cells ('super mobilizers') have improved survival in autologous stem cell transplantation for lymphoid malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 40, 437–441 (2007).

Jantunen, E. & Fruehauf, S. Importance of blood graft characteristics in auto-SCT: implications for optimizing mobilization regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 46, 627–635 (2011).

Giralt, S. et al. Optimizing autologous stem cell mobilization strategies to improve patient outcomes: consensus guidelines and recommendations. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 20, 295–308 (2014).

Lytton, S. D., Denton, C. P. & Nutzenberger, A. M. Treatment of autoimmune disease with rabbit anti-T lymphocyte globulin: clinical efficacy and potential mechanisms of action. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1110, 285–296 (2007).

Tomblyn, M. et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 15, 1143–1238 (2009).

Snowden, J. A. et al. Haematopoietic SCT in severe autoimmune diseases: updated guidelines of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 47, 770–790 (2012).

Styczynski, J. et al. Management of HSV, VZV and EBV infections in patients with hematological malignancies and after SCT: guidelines from the Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 43, 757–770 (2009).

Tappenden, P. et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: an exploratory cost-effectiveness analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 45, 1014–1021 (2010).

Socialstyrelsen. Vård vid multipel skleros och Parkinsons sjukdom. Stöd för styrning och ledning [Swedish]. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/ Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20392/2016-12-1.pdf (2016).

Gholipour, T., Healy, B., Baruch, N. F., Weiner, H. L. & Chitnis, T. Demographic and clinical characteristics of malignant multiple sclerosis. Neurology 76, 1996–2001 (2011).

Huisman, E. et al. Systematic literature review and network meta-analysis in highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and rapidly evolving severe multiple sclerosis. BMJ Open 7, e013430 (2017).

Kutzelnigg, A. et al. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain 128, 2705–2712 (2005).

Magliozzi, R. et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 130, 1089–1104 (2007).

Frischer, J. M. et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain 132, 1175–1189 (2009).

Rogne, S. Unethical for neurologists not to offer patients with multiple sclerosis chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 134, 1931–1932 (2014).

Acknowledgements

P.A.M. was supported by the UK MS Society [Grant no. 938/10 to P.M.], the Medical Research Council (MR/N026934/1) and the Italian MS Society (ref 22/16/F14) and is grateful for support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme. R.M. is supported by an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council (No. 340733) and the Neuroimmunology and MS Research Section by the Clinical Research Priority Project-MS of the University of Zurich. We gratefully acknowledge Manuela Badoglio from the EBMT Paris Study Office for providing data from the EBMT registry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.A.M. declares honoraria for speaking and travel support from Bayer, Biogen, Merck Serono and Novartis. G.L.M. has received support from Biogen (honoraria for lecturing, travel expenses for attending meetings and financial support for research), Genzyme (honorarium for lecturing), Merck Serono, Novartis, Teva (financial support for research) and Sanofi (honorarium for speaking). R.N. declares compensation and support from Biogen (principal investigator, funds for staff, research, organizing education, honorarium for speaking, advisory boards), Genzyme (honorarium for speaking, advisory boards, organizing education), NICE diagnostics advisory committee, Expert NICE Alemtuzumab committee; Novartis (principal investigator, honorarium for speaking, advisory boards), Roche (advisory boards). M.P.S. has received personal compensation for consulting services and for speaking activities from Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche and Teva. R.S. has received honoraria for lecturing from Sanofi.

Glossary

- Leukoapheresis

-

A process that separates white blood cells from the peripheral blood, which, in the context of AHSCT for MS, is carried out with a semi-automated medical device to harvest the patients autologous haematopoietic stem cell-enriched blood product after mobilization.

- Bone marrow aplasia

-

A state in which the bone marrow fails to generate adequate numbers of haematopoietic stem cells to repopulate the blood with red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets; in the context of AHSCT for MS, this state follows the conditioning regimen, irreversibly after myeloablative conditioning, which necessitates haematopoietic stem cell support for survival.

- Pattern II MS pathology

-

One of four described patterns of tissue pathology in MS, characterized by anti-myelin antibodies and complement factors.

- T cell receptor excision circles

-

Episomal DNA circles that are by-products of intra-thymic T cell receptor rearrangement and persist in T cells as detectable markers of their recent thymic origin.

- Recent thymic emigrants

-

T cells that have recently emerged from the thymus after differentiation and thymic selection.

- Antithymocyte globulin

-

A T-cell-depleting polyclonal immunoglobulin from horse or rabbit.

- Uhtoff phenomenon

-

The recurrence or worsening of pre-existing neurological symptoms, usually transient, experienced by patients with MS after exposure to internal (fever) or external (heat) high temperatures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muraro, P., Martin, R., Mancardi, G. et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 13, 391–405 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.81

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.81

This article is cited by

-

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation significantly alters circulating ceramides in peripheral blood of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients

Lipids in Health and Disease (2023)

-

Cell replacement therapy with stem cells in multiple sclerosis, a systematic review

Human Cell (2023)

-

Effect of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide on the Microglia Phenotype in Rats with Experimental Allergic Encephalomyelitis

Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis (2023)

-

The Use of Stem Cells as a Potential Treatment Method for Selected Neurodegenerative Diseases: Review

Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology (2023)

-

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate erectile dysfunction in rats with diabetes mellitus through the attenuation of ferroptosis

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2022)