Key Points

-

Six case studies illustrate how the common emergence of exotic vector-borne zoonotic infections depends on the three sequential steps of arrival, establishment and spread.

-

Within the marginally suitable environmental conditions of northern Europe, the re-establishment of malaria following its common importation in travellers is evidently impeded by non-biological factors. High standards of living allow effective control, and modern farming practices have reduced the rate of human biting by mosquitoes.

-

The widespread dispersal of a new vector, Aedes albopictus, largely through trade in used car tyres and other water-carrying goods, is determined by volume of traffic as well as climatic similarity to its original range. The vectorial capacity of this mosquito species for primate-transmitted dengue virus, however, is evidently limited by its feeding behaviour and ecology, usually resulting in much more modest outbreaks than are supported by Aedes aegypti.

-

A mutation that adapts chikungunya virus to transmission by A. albopictus has evidently occurred on three independent occasions that are associated with epidemics in the Indian Ocean islands (for example, La Réunion) and West Africa, and a short-lived outbreak in Italy. The potent combination of a vector disseminated by trade and a genetically labile virus repeatedly transported by infected travellers poses particular challenges for predictive risk mapping based on present knowledge.

-

Both West Nile and bluetongue viruses have been catapulted by human agency across major geographical barriers into the New World and northern Europe, respectively, where they found latently hospitable abiotic and biotic environments. The particular feeding behaviour of abundant and diverse American mosquitoes, aided by viral genetic change and high virulence in avian transmission hosts, created a different West Nile virus epidemiology to that observed in the Old World.

-

Since 1998 bluetongue virus has spread northwards into southern Europe, making apparently new use of resident Palaearctic midge vectors.

-

The epidemic of Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever in Turkey, still growing since 2002, illustrates that a markedly new epidemiological situation can arise in endemic regions. The cause is unknown, but historically such events elsewhere have been associated with disruption of stable environmental and social conditions through military and civil unrest, leading to greater abundance of, and human exposure to, infected ticks.

-

Predictive models can identify remote areas of similar climatic and host conditions to those in countries of origin of vectors and diseases, and thus can contribute to warnings of future potential emergence to allow public health services to develop preventive or rapid response measures. However, the development of new or more efficient vector pathways (for example, for West Nile and bluetongue viruses), subtle evolutionary changes in the pathogens (for example, in chikungunya virus) or changes in the socioeconomic conditions affecting the degree of human exposure to risk (for example, tick-borne encephalitis and possibly Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever) will limit the ability of models to predict the future based on past experience.

Abstract

The impact of human activities on the principles and processes governing the arrival, establishment and spread of exotic pathogens is illustrated by vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue, chikungunya, West Nile, bluetongue and Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fevers. Competent vectors, which are commonly already present in the areas, provide opportunities for infection by exotic pathogens that are introduced by travel and trade. At the same time, the correct combination of environmental conditions (both abiotic and biotic) makes many far-flung parts of the world latently and predictably, but differentially, permissive to persistent transmission cycles. Socioeconomic factors and nutritional status determine human exposure to disease and resistance to infection, respectively, so that disease incidence can vary independently of biological cycles.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–994 (2008). Meta-analysis of patterns in emerging diseases, but essential data largely tucked into the supplementary information.

Wolfe, N. D., Dunavan, C. P. & Diamond, J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature 447, 279–283 (2007).

Smith, A. D. et al. Imported malaria and high risk groups: observational study using UK surveillance data 1987–2006. BMJ 337, a120 (2008).

Doudier, B. et al. Possible autochthonous malaria from Marseille to Minneapolis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1236–1238 (2007).

Kuhn, K. G., Campbell-Lendrum, D. H., Armstrong, B. & Davies, C. R. Malaria in Britain: past, present and future. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9997–10001 (2003). A quantitative assessment of the various factors that drove malaria from Britain in the past century.

Poncon, N., Tran, A., Toty, C., Luty, A. J. F. & Fontenille, D. A quantitative risk assessment approach for mosquito-borne diseases: malaria re-emergence in southern France. Malaria J. 7, 147 (2008).

Poncon, N. et al. Biology and dynamics of potential malaria vectors in southern France. Malaria J. 6, 18 (2007).

Bryant, J. E., Holmes, E. C. & Barrett, A. D. T. Out of Africa: a molecular perspective on the introduction of yellow fever virus into the Americas. PLoS Pathog. 3, e75 (2007).

Hawley, W. A., Reiter, P., Copeland, R. S., Pumpuni, C. B. & Craig, G. B. Aedes albopictus in North America: probable introduction in used tires from northern Asia. Science 236, 1114–1115 (1987).

Reiter, P. & Sprenger, D. The used tire trade: a mechanism for the worldwide dispersal of container breeding mosquitoes. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 3, 494–501 (1987).

Dalla Pozza, G. L., Romi, R. & Severini, C. Source and spread of Aedes albopictus in the Veneto region of Italy. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 10, 589–592 (1994).

Scholte, E.-J. et al. First record of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus in the Netherlands. Europ. Mosq. Bull. 22, 5–9 (2007).

Rogers, D. J., Wilson, A. J., Hay, S. I. & Graham, A. J. The global distribution of yellow fever and dengue. Adv. Parasitol. 62, 182–220 (2006).

Knudsen, A. B., Romi, R. & Majori, G. Occurrence and spread in Italy of Aedes albopictus, with implications for its introduction into other parts of Europe. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 12, 177–183 (1996).

Romi, R., Di Luca, M. & Majori, G. Current status of Aedes albopictus and Aedes atropalpus in Italy. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 15, 425–427 (1999).

Romi, R. Aedes albopictus in Italy: an underestimated health problem. Ann. Inst. Super. Sanita 37, 241–247 (2001).

Hanson, S. & Craig, G. B. Cold acclimation, diapause, and geographic origin affect cold hardiness in eggs of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 31, 192–201 (1994).

Scholte, E.-J. & Schaffner, F. in Emerging Pests and Vector-borne Diseases in Europe. (eds Takken, W. & Knolls, B. G. J.) 241–260 (Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, 2007).

Schaffner, F. P. et al. Development of Aedes albopictus risk maps. (European Centre for Disease Control Prevention, Stockholm, 2009)

Tatem, A. J., Hay, S. I. & Rogers, D. J. Global traffic and disease vector dispersal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6242–6247 (2006). Combination of satellite-derived environmental data and human activities (shipping traffic), analysed with methods borrowed from molecular phylogenists.

Tatem, A. J. & Hay, S. I. Climatic similarity and biological exchange in the worldwide airline transportation network. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 274, 1489–1496 (2007).

Gratz, N. G. Critical review of the vector status of Aedes albopictus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 18, 215–227 (2004).

Rodhain, F. & Rosen, L. in Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. (eds Gubler, D. J. & Kuno, G.) 45–60 (CABI, Wallingford, 1997).

Service, M.W. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, introduced - Africa. ProMed mail [online], (2003).

Morens, D. M., Folkers, G. K. & Fauci, A. S. The challenge of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Nature 430, 242–249 (2004).

Gubler, D. J. Aedes albopictus in Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 751–752 (2003). An authoritative warning against the common assumption that an increase in one factor (in this case the distribution of the Asian tiger mosquito) will automatically lead to an upsurge in disease.

Reiter, P., Fontenille, D. & Paupy, C. Aedes albopictus as an epidemic vector of chikungunya virus: another emerging problem? Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 463–464 (2006).

Vazeille, M. et al. Two chikungunya isolates from the outbreak of La Reunion (Indian Ocean) exhibit different patterns of infection in the mosquito, Aedes albopictus. PLoS ONE 14, e1168 (2007).

Parola, P. et al. Novel chikungunya virus variant in travelers returning from Indian Ocean islands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1493–1499 (2006).

Vazeille, M., Jeannin, C., Martin, E., Schaffner, F. & Failloux, A.-B. Chikungunya: a risk for Mediterranean countries? Acta Tropica 105, 200–202 (2008).

Schuffenecker, I. et al. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS Med. 3, e263 (2006).

Pastorino, B. et al. Epidemic resurgence of chikungunya virus in Democratic Republic of the Congo: identification of a new central African strain. J. Med. Virol. 74, 277–282 (2004).

Laras, K. et al. Tracking the re-emergence of epidemic chikungunya virus in Indonesia. Trans. Roy. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99, 128–141 (2005).

Reiter, P. in Climate Change: the Impacts on the Epidemiology and Control of Animal Diseases (ed. de la Roque, S.) 383–398 (Office International des Epizooties /Word Organisation for Animal Health, Paris, 2008).

Tsetsarkin, K. A., Valandingham, D. L., McGee, C. E. & Higgs, S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 3, e201 (2007). Clear experimental evidence for the potential epidemiological impact of a single mutation in a virus within a complex vector-borne disease system.

Boelle, P. Y. et al. Investigating transmission in a two-wave epidemic of chikungunya fever, Reunion Island. Vector-Borne Zoon. Dis. 8, 207–217 (2008).

de Lambellerie, X. et al. Chikungunya virus adapts to tiger mosquito via evolutionary convergence: a sign of things to come? Virol. J. 3, 33 (2008). Neat combination of molecular and geographical phylogeny to reveal evolutionary events behind recent novel epidemics.

Pfeffer, M. & Loescher, T. Cases of chikungunya imported into Europe. Euro Surveill. 11, 2922 (2006).

Hochedez, P. et al. Chikungunya infection in travelers. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1565–1567 (2006).

Lanciotti, R. S. et al. Chikungunya virus in US travelers returning from India, 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 764–767 (2007).

Beltrame, A. et al. Imported chikungunya infection, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1264–1265 (2007).

Townson, H. & Nathan, M. B. Resurgence of chikungunya. Trans. Roy. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 308–309 (2008).

[No authors listed]. Chikungunya in Italy. (European Centre for Disease Control Prevention, Stockholm, 2007)

Rezza, G. et al. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet 370, 1840–1846 (2007).

Romi, R., Severini, F. & Toma, L. Cold acclimation and overwintering of female Aedes albopictus in Roma. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 22, 149–151 (2006).

Lanciotti, R. S. et al. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science 286, 2333–2337 (1999).

Hayes, C. G. West Nile virus: Uganda, 1937, to New York City, 1999. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 951, 25–37 (2001).

Hayes, C. G. et al. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1167–1173 (2005).

Apperson, C. S. et al. Host feeding patterns of established and potential mosquito vectors of West Nile virus in the eastern United States. Vector-Borne Zoon. Dis. 4, 71–82 (2004).

Hamer, G. L. et al. Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae): a bridge vector of West Nile virus to humans. J. Med. Entomol. 45, 125–128 (2008).

Kilpatrick, M. et al. West Nile virus risk assessment and the bridge vector paradigm. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 425–429 (2005).

Medlock, J. M., Snow, K. R. & Leach, S. Potential transmission of West Nile virus in the British Isles: an ecological review of candidate mosquito bridge vectors. Med. Vet. Entomol. 19, 2–21 (2005).

Kramer, L. D., Styer, L. M. & Ebel, G. D. A global perspective on the epidemiology of West Nile virus. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 53, 61–81 (2008). Comprehensive review of genetic, biological and environmental factors behind the emergence of WNV in North America within its global context.

Davis, C. T. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of North American West Nile virus isolates, 2001–2004: evidence for the emergence of a dominant genotype. Virology 342, 252–265 (2005).

Ebel, G. D., Carricaburu, J. E., Young, D. S., Bernard, K. A. & Kramer, L. D. Genetic and phenotypic variation of West Nile virus in New York, 2000–2003. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 71, 493–500 (2004).

Snapinn, K. W. et al. Declining growth rate of West Nile virus in North America. J. Virol. 81, 2531–2534 (2007).

Taylor, R. M., Work, T. H., Hurlbut, H. S. & Rizk, F. A study of the ecology of West Nile virus in Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 5, 579–620 (1956).

Hubalek, Z. & Halouzka, J. West Nile virus - a reemerging mosquito-borne viral disease in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5, 643–650 (1999).

Tsai, T. F., Popovici, F., Cernescu, C., Campbell, G. L. & Nedelcu, N. I. West Nile encephalitis epidemic in southeastern Romania. Lancet 352, 767–771 (1998).

Savage, H. M. et al. Entomologic and avian investigations of an epidemic of West Nile fever in Romania in 1996, with serologic and molecular characterization of a virus isolate from mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61, 600–611 (1999).

Platonov, A. E. et al. Outbreak of West Nile virus infection, Volgograd region, Russia, 1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 128–132 (2001).

Miller, B. M. et al. First field evidence for natural vertical transmission of West Nile virus in Culex univittatus complex mosquitoes from Rift Valley Province, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62, 240–246 (2000).

Nasci, R. S. et al. West Nile virus in overwintering Culex mosquitoes, New York City, 2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 742–744 (2001).

Chevalier, V. et al. Serological assessment of West Nile fever virus activity in the pastoral system of Ferlo, Senegal. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1081, 216–225 (2006).

Steele, K. E. et al. Pathology of fatal West Nile virus infections in native and exotic birds during the 1999 outbreak in New York City, New York. Vet. Pathol. 37, 208–224 (2000).

Komar, N. et al. Experimental infection of North American birds with the New York 1999 strain of West Nile virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9, 311–322 (2003).

Dawson, J. R. et al. Crow deaths caused by West Nile virus during winter. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1912–1914 (2007).

Miller, D. L. et al. West Nile virus in farmed alligators. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9, 794–799 (2003).

Kostiukov, M. A., Alekseev, A. N., Bulychev, V. P. & Gordeeva, Z. E. Experimental evidence for infection of Culex pipiens L. mosquitoes by West Nile fever virus from Rana ridibunda Pallas and its transmission by bites (in Russian). Med. Parazitol. Parazit. Bol. 6, 76–78 (1986).

Sbrana, E. et al. Oral transmission of West Nile virus in a hamster model. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72, 325–329 (2005).

Bakonyi, T., Hubalek, Z., Rudolf, I. & Nowotny, N. Novel flavivirus or new lineage of West Nile virus, Central Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 225–231 (2005).

Hay, S. I., Graham, A. J. & Rogers, D. J. (eds) Global Mapping of Infectious Diseases: Methods, Examples and Emerging Applications. (Academic Press, London, 2006). Clear exposition of methods to describe, explain and predict global patterns of infectious disease distributions, plus case studies on viral and parasitic infections.

Purse, B. V., Brown, H. E., Harrup, L., Mertens, P. P. C. & Rogers, D. J. in Climate Change: the Impacts on the Epidemiology and Control of Animal Diseases (ed. de la Roque, S.) (Office International des Epizooties /Word Organisation for Animal Health, Paris, 2008). Environmental changes and biological processes behind the northward spread of bluetongue virus into Europe, 1998–2005.

Mellor, P. S. & Boorman, J. The transmission and geographical spread of African horse sickness and bluetongue viruses. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 89, 1–15 (1995).

Purse, B. V. et al. Climate change and the recent emergence of bluetongue in Europe. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 3, 171–181 (2005).

De Liberato, C., Purse, B. V., Goffredo, M., Scholl, F. & Scaramozzino, P. Geographical and seasonal distribution of the bluetongue virus vector, Culicoides imicola, in central Italy. Med. Vet. Entomol. 17, 388–394 (2003).

Torino, A., Caracappa, S., Mellor, P. S., Baylis, M. & Purse, B. V. Spatial distribution of bluetongue virus and its Culicoides vectors in Sicily. Med. Vet. Entomol. 18, 81–89 (2004).

Purse, B. V. et al. Incriminating bluetongue virus vectors with climate envelope models. J. Appl. Ecol. 44, 1231–1242 (2007).

Mellor, P. S., Carpenter, S. R., Harrup, L., Baylis, M. & Mertens, P. P. C. Bluetongue in Europe and the Mediterranean basin: history of occurrence prior to 2006. Prev. Vet. Med. 87, 4–20 (2008). Essential catalogue of bluetongue outbreaks in southern Europe, with plausible explanations.

Ducheyne, E. et al. Quantifying the wind dispersal of Culicoides species in Greece and Bulgaria. Geospat. Health 2, 177–189 (2007).

Mellor, P. S., Rawlings, P., Baylis, M. & Welby, M. P. Effect of temperature on African horse sickness virus in Culicoides. Arch. Virol. 14, 155–163 (1998).

Paweska, J. T., Venter, G. J. & Mellor, P. S. Vector competence of South African Culicoides species for bluetingue virus serotype 1 (BTV-1) with special reference to the effect of temperature on the rate of virus replication in C. imicola and C. bolitinos. Med. Vet. Entomol. 16, 10–21 (2002).

Wittman, E. J., Mellor, P. S. & Baylis, M. Effect of temperature on the transmission of orbiviruses by the biting midge, Culicoides sonoresis. Med. Vet. Entomol. 16, 147–156 (2002).

Mintiens, K. et al. Possible routes of intoduction of bluetongue virus serotype 8 into the epicentre of the 2006 epidemic in north-western Europe. Prev. Vet. Med. 87, 131–144 (2008).

Gloster, J., Burgin, L., Witham, C., Athanassiadou, M. & Mellor, P. S. Bluetongue in the United Kingdom and northern Europe in 2007 and key issues for 2008. Vet. Rec. 162, 298–302 (2008).

Burgin, L., Gloster, J. & Mellor, P. S. Why were there no outbreaks of bluetongue in the UK during 2008? Vet. Rec. 164, 384–387 (2009).

Hendrickx, G. et al. A wind density model to quantify the airborne spread of Culicoides species during north-western Europe bluetongue epidemic, 2006. Prev. Vet. Med. 87, 162–181 (2008).

Wilson, A., Darpel, K. & Mellor, P. S. Where does bluetongue virus sleep in the winter? PLoS Biol. 6, e210 (2008).

Takamatsu, H. et al. A possible overwintering mechanism for bluetongue virus in the absence of the insect vector. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 227–235 (2003).

De Clercq, K. et al. Transplacental bluetongue infection in cattle. Vet. Rec. 162, 564 (2008).

Christova, I. et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, southwestern Bulgaria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 983–985 (2009).

Hoogstraal, H. The epidemiology of tick borne Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Asia, Europe and Africa. J. Med. Entomol. 15, 307–417 (1979).

Randolph, S. E. & Rogers, D. J. in Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (eds Ergönül, O. & Whitehouse, C. A.) 167–186 (Springer, Dordecht, 2007).

Vatansever, Z., Uzun, R., Estrada-Pena, A. & Ergonul, O. in Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever: A Global Perspective. (eds Ergönül, O. & Whitehouse, C. A.) 59–74 (Springer, Dordecht, 2007).

Gunes, T. et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in high risk population, Turkey. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 461–464 (2009).

Ergönül, O. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 203–214 (2006).

Karti, S. S., Odabasi, Z. & Korten, V. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 1379–1384 (2004).

Avsic-Zupanc, T. in Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever: A Global Perspective. (eds Ergonul, O. & Whitehouse, C. A.) 75–88 (Springer, Dordecht, 2007).

Ergönül, O. Treatment of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 78, 125–131 (2008).

Estrada-Peña, A. et al. Modeling the spatial distribution of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever outbreak in Turkey. Vector-Borne Zoon. Dis. 7, 667–678 (2007).

Midilli, K. et al. Imported Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever cases in Istanbul. BMC Infect. Dis. 7, 54 (2007).

Randolph, S. E. & Šumilo, D. in Emerging Pests and Vector-borne Disease in Europe (eds Takken, W. & Knols, B. G. J.) 187–206 (Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, 2007).

Ergönül, O., Akgunduz, S., Kocaman, I., Vatansever, Z. & Korten, V. Changes in temperature and the Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever outbreak in Turkey. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11 (Suppl. 2), 360 (2005).

Šumilo, D. et al. Socio-economic factors in the differential upsurge of tick-borne encephalitis in Central and Eastern Europe. Rev. Med. Virol. 18, 81–95 (2008). Extensive detailed data making a compelling case for the role of human activities, driven by socioeconomic consequences of political reform, in tick-borne disease emergence in Europe.

Šumilo, D. et al. Behavioural responses to perceived risk of tick-borne encephalitis: vaccination and avoidance in the Baltics and Slovenia. Vaccine 26, 2580–2588 (2008).

Randolph, S. E. Tick-borne encephalitis incidence in Central and Eastern Europe: consequences of political transition. Micr. Infect. 10, 209–216 (2008).

Elith, J. et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species' distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29, 129–151 (2006). Comparative review to help make sense of the burgeoning range of statistical methods increasingly used for species distribution modelling.

Capela, R. et al. Spatial distribution of Culicoides species in Portugal in relation to the transmission of African horse sickness and bluetongue viruses. Med. Vet. Entomol. 17, 165–177 (2003).

Tatem, A. J. et al. Prediction of bluetongue vector distribution in Europe and North Africa using satellite imagery. Vet. Microbiol. 97, 13–29 (2003).

[No authors listed.] Focus on Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever. Arbo-zoonet newletter 2 [online], (2008).

Acknowledgements

S.E.R. is grateful to the organizers of the Keystone Symposium in Bangkok in October 2008, where her lecture triggered this invited review. S.E.R. is partially supported by the European Union grant GOCE-2003-010,284 EDEN; this paper is catalogued by the EDEN Steering Committee as EDEN0156 (http://www.eden-fp6project.net). The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

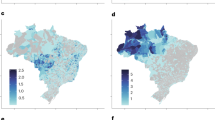

Supplementary information S1 | Figure 4

Bluetongue virus distribution in Europe, a) predicted in 2002 according to methods described in text (pale green, zero/low abundance; yellow, intermediate abundance; dark green, high abundance; grey, no predictions), and b) observed. (PDF 1242 kb)

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

Entrez Genome

Entrez Genome Project

FURTHER INFORMATION

Glossary

- Zoonosis

-

An infectious agent that is maintained by transmission among wildlife hosts and that only infects humans by their incidental contact with infected wild hosts or vectors. No human to human transmission is possible unless the pathogen evolves to achieve this.

- Anthropophilic

-

Showing preferences for humans. In this case, anthropophilic refers to a vector's feeding behaviour.

- Catholic feeding behaviour

-

Feeding from a wide range of hosts, typically owing to opportunism rather than specialization.

- Sylvatic cycle

-

Cycle of infectious agent maintained among wild animals, especially those living in forests.

- Transovarially

-

An infectious agent being transmitted vertically from female to the next generation through the eggs.

- Enzootic

-

When a zoonosis is habitually present in a wildlife population, rather than appearing only periodically as an epidemic in human populations.

- Ornithophilic

-

Showing preferences for birds. In this case ornithophilic refers to the vectors' feeding behaviour.

- Patent infection

-

An infection in which the infectious agent is shed from the patient.

- Serotypes

-

A particular strain of a pathogen defined by its stimulation of a specific immune response.

- Lagomorph

-

An animal belonging to an order of mammals that includes rabbits and hares.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Randolph, S., Rogers, D. The arrival, establishment and spread of exotic diseases: patterns and predictions. Nat Rev Microbiol 8, 361–371 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2336

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2336

This article is cited by

-

Unexpected behavioural adaptation of yellow fever mosquitoes in response to high temperatures

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

From Alien Species to Alien Communities: Host- and Habitat-Associated Microbiomes in an Alien Amphibian

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Molecular detection of Babesia microti in dromedary camels in Egypt

Tropical Animal Health and Production (2023)

-

Optimization of adult mosquito trap settings to monitor populations of Aedes and Culex mosquitoes, vectors of arboviruses in La Reunion

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Climate change accelerates winter transmission of a zoonotic pathogen

Ambio (2022)