Key Points

-

Mammalian spermatozoa employ at least two guidance mechanisms: chemotaxis and thermotaxis. These mechanisms are restricted to capacitated spermatozoa only, constituting ∼10% of the sperm population in humans.

-

The capacitated, chemotactic, thermotactic state is temporary and its timing in different mammalian species seems to be programmed according to the time at which an ovulated egg is available in the female genital tract.

-

Sperm chemoattractants are secreted from both the egg and its surrounding cumulus cells. One chemoattractant that is secreted from the cumulus cells is progesterone, which is active in the pM concentration range.

-

One of the chemotaxis receptors on human spermatozoa is an olfactory receptor, OR17-4. Its agonist, the floral scent bourgeonal, acts as a sperm chemoattractant in vitro.

-

Progesterone and bourgeonal each cause a transient rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, which results in a behavioural response. The signalling cascade that mediates these responses is not known for either of these chemoattractants.

-

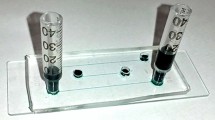

At ovulation, the temperature at the sperm's storage site decreases by almost 1°C in rabbits, resulting in an ovulation-dependent temperature gradient that can be exploited for sperm thermotaxis from the storage to the fertilization site.

-

Sperm guidance to the egg in the mammalian female genital tract seems to be a multistep process, involving long-range thermotaxis and at least two, possibly more, steps of chemotaxis.

Abstract

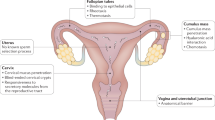

Contrary to the prevalent view, there seems to be no competition in the mammalian female genital tract among large numbers of sperm cells that are racing towards the egg. Instead, small numbers of the ejaculated sperm cells enter the Fallopian tube, and these few must be guided to make the remaining long, obstructed way to the egg. Here, we review the mechanisms by which mammalian sperm cells are guided to the egg.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Harper, M. J. K. in Germ Cells and Fertilization, Vol. 1 (eds Austin, C. R. & Short, R. V.) 102–127 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, England, 1982).

Williams, M. et al. Sperm numbers and distribution within the human Fallopian tube around ovulation. Hum. Reprod. 8, 2019–2026 (1993).

Eisenbach, M. & Tur-Kaspa, I. Do human eggs attract spermatozoa? BioEssays 21, 203–210 (1999).

Jaiswal, B. S. & Eisenbach, M. in Fertilization (ed. Hardy, D. M.) 57–117 (Academic Press, San Diego, 2002).

Cohen-Dayag, A., Tur-Kaspa, I., Dor, J., Mashiach, S. & Eisenbach, M. Sperm capacitation in humans is transient and correlates with chemotactic responsiveness to follicular factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11039–11043 (1995). This paper, together with reference 12, demonstrates for the first time that only capacitated spermatozoa are chemotactic. These reports further show that the capacitated, chemotactic state is transient and that different spermatozoa become capacitated/chemotactic at different time points, resulting in the continuous replacement of capacitated, chemotactic cells in a sperm population.

Giojalas, L. C., Rovasio, R. A., Fabro, G., Gakamsky, A. & Eisenbach, M. Timing of sperm capacitation appears to be programmed according to egg availability in the female genital tract. Fertil. Steril. 82, 247–249 (2004). First report to provide evidence that mammalian spermatozoa become capacitated and chemotactic when, and for as long as, they have a chance to find a fertilizable egg in the oviduct.

Eisenbach, M. Chemotaxis (Imperial College Press, London, 2004).

Bahat, A. et al. Thermotaxis of mammalian sperm cells: a potential navigation mechanism in the female genital tract. Nature Med. 9, 149–150 (2003). First demonstration that spermatozoa are guided by thermotaxis.

Miller, R. L. in Biology of Fertilization, Vol. 2 (eds Metz, C. B. & Monroy, A.) 275–337 (Academic Press, New York, 1985).

Cosson, M. P. in Controls of Sperm Motility: Biological and Clinical Aspects (ed. Gagnon, C.) 103–135 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 1990).

Eisenbach, M. Sperm chemotaxis. Rev. Reprod. 4, 56–66 (1999).

Cohen-Dayag, A. et al. Sequential acquisition of chemotactic responsiveness by human spermatozoa. Biol. Reprod. 50, 786–790 (1994).

Fabro, G. et al. Chemotaxis of capacitated rabbit spermatozoa to follicular fluid revealed by a novel directionality-based assay. Biol. Reprod. 67, 1565–1571 (2002).

Oliveira, R. G., Tomasi, L., Rovasio, R. A. & Giojalas, L. C. Increased velocity and induction of chemotactic response in mouse spermatozoa by follicular and oviductal fluids. J. Reprod. Fertil. 115, 23–27 (1999).

Villanueva-Díaz, C., Vadillo-Ortega, F., Kably-Ambe, A., Diaz-Perez, M. A. & Krivitzky, S. K. Evidence that human follicular fluid contains a chemoattractant for spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. 54, 1180–1182 (1990).

Ralt, D. et al. Sperm attraction to a follicular factor(s) correlates with human egg fertilizability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 2840–2844 (1991). Demonstrates, for the first time, a remarkable correlation between human sperm accumulation in follicular fluid and egg fertilization.

Ralt, D. et al. Chemotaxis and chemokinesis of human spermatozoa to follicular factors. Biol. Reprod. 50, 774–785 (1994). An in-depth investigation of the cause of sperm accumulation in follicular fluid, and the first report that mammalian spermatozoa respond by chemotaxis to follicular fluid.

Al-Anzi, B. & Chandler, D. E. A sperm chemoattractant is released from Xenopus egg jelly during spawning. Dev. Biol. 198, 366–375 (1998).

Giojalas, L. C. & Rovasio, R. A. Mouse spermatozoa modify their dynamic parameters and chemotactic response to factors from the oocyte microenvironment. Int. J. Androl. 21, 201–206 (1998).

Navarro, M. C., Valencia, J., Vazquez, C., Cozar, E. & Villanueva, C. Crude mare follicular fluid exerts chemotactic effects on stallion spermatozoa. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 33, 321–324 (1998).

Serrano, H., Canchola, E. & García-Suárez, M. D. Sperm-attracting activity in follicular fluid associated to an 8.6-kDa protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 283, 782–784 (2001).

Wildt, L., Kissler, S., Licht, P. & Becker, W. Sperm transport in the human female genital tract and its modulation by oxytocin as assessed by hysterosalpingoscintigraphy, hysterotonography, electrohysterography and Doppler sonography. Hum. Reprod. Update 4, 655–666 (1998).

Tur-Kaspa, I. in Tubal Catheterization (ed. Gleicher, N.) 5–14 (Wiley-Liss, New York, 1992).

Bahat, A., Eisenbach, M. & Tur-Kaspa, I. Periovulatory increase in temperature difference within the rabbit oviduct. Hum. Reprod. 20, 2118–2121 (2005).

Flechon, J.-E. & Hunter, R. H. F. Distribution of spermatozoa in the utero-tubal junction and isthmus of pigs, and their relationship with the luminal epithelium after mating: a scanning electron microscope study. Tissue Cell 13, 127–139 (1981).

Sun, F. et al. Human sperm chemotaxis: both the oocyte and its surrounding cumulus cells secrete sperm chemoattractants. Hum. Reprod. 20, 761–767 (2005). First indication that a mature egg and its surrounding cumulus layer each secrete sperm chemoattractants.

Battalia, D. E. & Yanagimachi, R. Enhanced and co-ordinated movement of the hamster oviduct during the periovulatory period. J. Reprod. Fert. 56, 515–520 (1979).

David, A., Vilensky, A. & Nathan, H. Temperature changes in the different parts of the rabbit's oviduct. Int. J. Gynaec. Obstet. 10, 52–56 (1972).

Hunter, R. H. F. & Nichol, R. A preovulatory temperature gradient between the isthmus and the ampulla of pig oviducts during the phase of sperm storage. J. Reprod. Fert. 77, 599–606 (1986).

Bedford, J. M. in Germ Cells and Fertilization, Vol. 1 (eds Austin, C. R. & Short, R. V.) 128–163 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1982).

Bedford, J. M. & Kim, H. H. Cumulus oophorus as a sperm sequestering device, in vivo. J. Exp. Zool. 265, 321–328 (1993).

Gomendio, M., Harcourt, A. H. & Roldán, E. R. S. in Sperm Competition and Sexual Selection (eds Birkhead, T. R. & Moller, A. P.) 667–751 (Academic Press, London, 1998).

Sun, F. et al. Lack of species-specificity in mammalian sperm chemotaxis. Dev. Biol. 255, 423–427 (2003).

Eisenbach, M. Mammalian sperm chemotaxis and its association with capacitation. Dev. Genet. 25, 87–94 (1999).

Spehr, M. et al. Particulate adenylate cyclase plays a key role in human sperm olfactory receptor-mediated chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40194–40203 (2004).

Spehr, M. et al. Identification of a testicular odorant receptor mediating human sperm chemotaxis. Science 299, 2054–2058 (2003). The first identification of a specific chemotaxis receptor, an olfactory receptor, on mammalian spermatozoa.

Gould, J. E., Overstreet, J. W. & Hanson, F. W. Assessment of human sperm function after recovery from the female reproductive tract. Biol. Reprod. 31, 888–894 (1984).

Hunter, R. H. F. Human fertilization in vivo, with special reference to progression, storage and release of competent spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 2, 329–332 (1987).

Morisawa, M. Cell signaling mechanisms for sperm motility. Zool. Sci. 11, 647–662 (1994).

Yoshida, M., Murata, M., Inaba, K. & Morisawa, M. A chemoattractant for ascidian spermatozoa is a sulfated steroid. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14831–14836 (2002).

Bömer, M. et al. Ca2+ spikes in the flagellum control chemotactic behavior of sperm. EMBO J. 24, 2741–2752 (2005).

Ishijima, S. & Mohri, H. in Controls of Sperm Motility: Biological and Clinical Aspects (ed. Gagnon, C.) 29–42 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 1990).

Kaupp, U. B. et al. The signal flow and motor response controlling chemotaxis of sea urchin sperm. Nature Cell Biol. 5, 109–117 (2003). This report, together with reference 41, demonstrates that a chemoattractant initiates a rapid and transient rise in the concentration of cyclic GMP in sea-urchin spermatozoa, followed by a transient influx of Ca2+ and resulting in a motor response.

Luconi, M. et al. Identification and characterization of functional nongenomic progesterone receptors on human sperm membrane. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 83, 877–885 (1998).

Macnab, R. M. & Koshland, D. E. The gradient-sensing mechanism in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 69, 2509–2512 (1972).

Villanueva-Díaz, C., Arias-Martínez, J., Bermejo-Martínez, L. & Vadillo-Ortega, F. Progesterone induces human sperm chemotaxis. Fertil. Steril. 64, 1183–1188 (1995).

Sliwa, L. Effect of some sex steroid hormones on human spermatozoa migration in vitro. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 58, 173–175 (1995).

Wang, Y., Storeng, R., Dale, P. O., Åbyholm, T. & Tanbo, T. Effects of follicular fluid and steroid hormones on chemotaxis and motility of human spermatozoa in vitro. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 15, 286–292 (2001).

Jaiswal, B. S., Tur-Kaspa, I., Dor, J., Mashiach, S. & Eisenbach, M. Human sperm chemotaxis: is progesterone a chemoattractant? Biol. Reprod. 60, 1314–1319 (1999).

Teves, M. E. et al. Progesterone at the pM range is a chemoattractant for mammalian spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. (in the press).

Fukuda, N., Yomogida, K., Okabe, M. & Touhara, K. Functional characterization of a mouse testicular olfactory receptor and its role in chemosensing and in regulation of sperm motility. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5835–5845 (2004).

Schall, T. J., Bacon, K., Toy, K. J. & Goeddel, D. V. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature 347, 669–671 (1990).

Alam, R. et al. RANTES is a chemotactic and activating factor for human eosinophils. J. Immunol. 150, 3442–3448 (1993).

Isobe, T. et al. The effect of RANTES on human sperm chemotaxis. Hum. Reprod. 17, 1441–1446 (2002).

Brenner, B. M., Ballerman, B. J., Gunning, M. E. & Zeidel, M. L. Diverse biological actions of atrial natriuretic peptide. Physiol. Rev. 70, 665–699 (1990).

Ruskoaho, H. Atrial natriuretic peptide: synthesis, release, and metabolism. Pharmacol. Rev. 44, 481–602 (1992).

Sundfjord, J. A., Forsdahl, F. & Thibault, G. Physiological levels of immunoreactive ANH-like peptides in human follicular fluid. Acta Endocrinol. 121, 578–580 (1989).

Silvestroni, L., Palleschi, S., Guglielmi, R. & Croce, C. T. Identification and localization of atrial natriuretic factor receptors in human spermatozoa. Arch. Androl. 28, 75–82 (1992).

Zamir, N. et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide attracts human spermatozoa in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 197, 116–122 (1993).

Anderson, R. A., Feathergill, K. A., Rawlins, R. G., Mack, S. R. & Zaneveld, L. J. D. Atrial natriuretic peptide: a chemoattractant of human spermatozoa by a guanylate cyclase-dependent pathway. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 40, 371–378 (1995).

Olson, J. H. et al. Allurin, a 21-kDa sperm chemoattractant from Xenopus egg jelly, is related to mammalian sperm-binding proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11205–11210 (2001).

Xiang, X., Burnett, L., Rawls, A., Bieber, A. & Chandler, D. The sperm chemoattractant 'allurin' is expressed and secreted from the Xenopus oviduct in a hormone-regulated manner. Dev. Biol. 275, 343–355 (2004).

Ziegler, A., Dohr, G. & Uchanska-Ziegler, B. Possible roles for products of polymorphic MHC and linked olfactory receptor genes during selection processes in reproduction. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 48, 34–42 (2002).

Darszon, A., Beltran, C., Felix, R., Nishigaki, T. & Trevino, C. L. Ion transport in sperm signaling. Develop. Biol. 240, 1–14 (2001).

Eisenbach, M. Towards understanding the molecular mechanism of sperm chemotaxis. J. Gen. Physiol. 124, 105–108 (2004).

Solzin, J. et al. Revisiting the role of H+ in chemotactic signaling of sperm. J. Gen. Physiol. 124, 115–124 (2004).

Matsumoto, M. et al. A sperm-activating peptide controls a cGMP-signaling pathway in starfish sperm. Dev. Biol. 260, 314–324 (2003).

Singh, S. et al. Membrane guanylate cyclase is a cell-surface receptor with homology to protein kinases. Nature 334, 708–712 (1988).

Bentley, J. K., Tubb, D. J. & Garbers, D. L. Receptor-mediated activation of spermatozoan guanylate cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 14859–14862 (1986).

Ward, G. E., Brokaw, C. J., Garbers, D. L. & Vacquier, V. D. Chemotaxis of Arbacia punctulata spermatozoa to resact, a peptide from the egg jelly layer. J. Cell Biol. 101, 2324–2329 (1985). The first identification of a specific, egg-derived sperm chemoattractant in metazoa.

Cook, S. P., Brokaw, C. J., Muller, C. H. & Babcock, D. F. Sperm chemotaxis: egg peptides control cytosolic calcium to regulate flagellar responses. Dev. Biol. 165, 10–19 (1994).

Wood, C. D., Nishigaki, T., Furuta, T., Baba, S. A. & Darszon, A. Real-time analysis of the role of Ca2+ in flagellar movement and motility in single sea urchin sperm. J. Cell Biol. 169, 725–731 (2005).

Brokaw, C. J., Josslin, R. & Bobrow, L. Calcium ion regulation of flagellar beat symmetry in reactivated sea urchin spermatozoa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 58, 795–800 (1974).

Parmentier, M. et al. Expression of members of the putative olfactory receptor gene family in mammalian germ cells. Nature 355, 453–455 (1992). The first demonstration of olfactory receptor transcripts on germ cells.

Branscomb, A., Seger, J. & White, R. L. Evolution of odorant receptors expressed in mammalian testes. Genetics 156, 785–797 (2000).

Vanderhaeghen, P., Schurmans, S., Vassart, G. & Parmentier, M. Olfactory receptors are displayed on dog mature sperm cells. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1441–1452 (1993).

Vanderhaeghen, P., Schurmans, S., Vassart, G. & Parmentier, M. Specific repertoire of olfactory receptor genes in the male germ cells of several mammalian species. Genomics 39, 239–246 (1997).

Walensky, L. D., Roskams, A. J., Lefkowitz, R. J., Snyder, S. H. & Ronnett, G. V. Odorant receptors and desensitization proteins colocalize in mammalian sperm. Mol. Med. 1, 130–141 (1995).

Walensky, L. D. et al. Two novel odorant receptor families expressed in spermatids undergo 5′-splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9378–9387 (1998).

Defer, N. et al. The olfactory adenylyl cyclase type 3 is expressed in male germ cells. FEBS Lett. 424, 216–220 (1998).

Gautier-Courteille, C., Salanova, M. & Conti, M. The olfactory adenylyl cyclase III is expressed in rat germ cells during spermiogenesis. Endocrinology 139, 2588–2599 (1998).

Asai, H. et al. Genomic structure and transcription of a murine odorant receptor gene: differential initiation of transcription in the olfactory and testicular cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 221, 240–247 (1996).

Blackmore, P. F. & Lattanzio, F. A. Cell surface localization of a novel non-genomic progesterone receptor on the head of human sperm. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 181, 331–336 (1991).

Meizel, S. & Turner, K. O. Progesterone acts at the plasma membrane of human sperm. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 77, R1–R5 (1991).

Harper, C. V., Barratt, C. L. & Publicover, S. J. Stimulation of human spermatozoa with progesterone gradients to simulate approach to the oocyte. Induction of [Ca2+]i oscillations and cyclical transitions in flagellar beating. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46315–46325 (2004).

Calogero, A. E. et al. Effects of progesterone on sperm function: mechanisms of action. Hum. Reprod. 15 (Suppl. 1), 28–45 (2000).

Luck, M. R. et al. Follicular fluid responds endothermically to aqueous dilution. Hum. Reprod. 16, 2508–2514 (2001).

Leese, H. J. The formation and function of oviduct fluid. J. Reprod. Fertil. 82, 843–856 (1988).

Cicinelli, E. et al. Blood to the cornual area of the uterus is mainly supplied from the ovarian artery in the follicular phase and from the uterine artery in the luteal phase. Hum. Reprod. 19, 1003–1008 (2004).

Harper, M. J. K. in The Physiology of Reproduction, Vol. 1 (eds Knobil, E. & Neill, J. D.) 123–187 (Raven Press, New York, 1994).

Suarez, S. S. in Fertilization (ed. Hardy, D. M.) 3–28 (Academic Press, San Diego, 2002).

Manor, M. Identification and Purification of Female-Originated Chemotactic Factors. Ph.D. Thesis, The Weizmann Institute of Science (1994).

Sliwa, L. Chemotaction of mouse spermatozoa induced by certain hormones. Arch. Androl. 35, 105–110 (1995).

Sliwa, L. Chemotactic effect of hormones in mouse spermatozoa. Arch. Androl. 32, 83–88 (1994).

Lee, S.-L., Kao, C.-C. & Wei, Y.-H. Antithrombin III enhances the motility and chemotaxis of boar sperm. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 107A, 277–282 (1994).

Sliwa, L. Substance P and beta-endorphin act as possible chemoattractants of mouse sperm. Arch. Androl. 46, 135–140 (2001).

Sliwa, L. Effect of heparin on human spermatozoa migration in vitro. Arch. Androl. 30, 177–181 (1993).

Sliwa, L. Heparin as a chemoattractant for mouse spermatozoa. Arch. Androl. 31, 149–152 (1993).

Sliwa, L. Hyaluronic acid and chemoattractant substance from follicular fluid: in vitro effect of human sperm migration. Arch. Androl. 43, 73–76 (1999).

Acknowledgements

M.E. is an incumbent of Jack and Simon Djanogly Professorial Chair in Biochemistry. L.C.G. is a member of the research staff of the National Council of Research (CONICET, Argentina).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Glossary

- Capacitation

-

A ripening process that spermatozoa must undergo in order to penetrate the female's egg and fertilize it.

- Acrosome reaction

-

The release of proteolytic enzymes from the top part of the sperm's head, known as the acrosome, which enables sperm penetration through the egg coat.

- Chemotaxis

-

The movement of cells in the direction of a chemoattractant gradient.

- Chemoattractant

-

A factor (a peptide or any other chemical) that attracts specific cells by chemotaxis.

- Thermotaxis

-

The movement of cells that is directed according to a temperature gradient.

- Follicular fluid

-

A fluid consisting of sex steroid hormones, plasma proteins, mucopolysaccharides and electrolytes that surrounds the ovum in the vesicular ovarian follicle (Graafian follicle).

- Oviduct

-

A tube between the ovary and the uterus, through which the egg is transported from the former to the latter and in which fertilization occurs. It consists of two parts: the isthmus — a narrow part that is closer to the uterus — and the ampulla — a wider part that is closer to the ovary.

- Cumulus cells

-

The cells that form dense layers surrounding a mature egg.

- Axoneme

-

An axial filament complex at the centre of the sperm tail.

- Hydrozoa

-

A class of radially symmetrical marine or freshwater invertebrates of the phylum Cnidaria, with one end of the body bearing the mouth and tentacles. This class includes polyps and medusa.

- Hydromedusa

-

A hydrozoan in the medusoid stage of its life cycle.

- Ascidian

-

A marine invertebrate animal that has a transparent sac-shaped body with openings through which water passes; also known as sea squirt.

- Chemokinesis

-

The speed enhancement of actively moving cells in response to a stimulus.

- Photorelease

-

The rapid release of a compound from its caged (protected) analogue by a short pulse of light.

- Hyperactivation

-

A motility pattern that is characterized by increased velocity, decreased linearity, increased amplitude of lateral head displacement, and flagellar whiplash movement.

- Granulosa cells

-

The cells that form layers surrounding the oocyte within the follicle.

- Olfactory receptor

-

An integral membrane protein that is associated with a G-protein and is involved in effecting the sense of smell.

- Spermatid

-

An immature gamete that develops into a spermatozoon.

- Nuclear progesterone receptor

-

A progesterone-inducible transcription factor that is located intracellularly.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eisenbach, M., Giojalas, L. Sperm guidance in mammals — an unpaved road to the egg. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7, 276–285 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1893

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1893

This article is cited by

-

Microfluidics as an emerging paradigm for assisted reproductive technology: A sperm separation perspective

Biomedical Microdevices (2024)

-

Advances in microfluidic technology for sperm screening and in vitro fertilization

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2024)

-

Heroes and Helpmeets

Science & Education (2024)

-

Dual enzyme-powered chemotactic cross β amyloid based functional nanomotors

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Survival strategies of artificial active agents

Scientific Reports (2023)