Key Points

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors promote an antitumour immune response by blocking signalling via either the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) pathway or the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) pathway

-

Their use can result in immune-related adverse events, including the development of gastrointestinal inflammation, which shares certain clinicopathological features with IBD

-

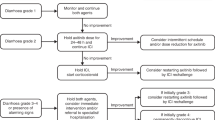

In suspected cases of persistent mild or moderate-to-severe immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced gastrointestinal inflammation, endoscopic and histological investigation should be arranged to confirm the diagnosis, and other possible causes of symptoms should be excluded

-

Corticosteroids should be used in the first instance to manage inflammation, and in patients who are refractory to corticosteroids, the addition of infliximab or vedolizumab should be considered

Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies are a novel group of monoclonal antibodies with proven effectiveness in a wide range of malignancies, including melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, urothelial carcinoma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Their use in a range of other indications, such as gastrointestinal and head and neck cancer, is currently under investigation. The number of agents included in this drug group is increasing, as is their use. Although they have the potential to improve the treatment of advanced malignancies, they are also associated with a substantial risk of immune-related adverse events. The incidence of gastrointestinal toxicity associated with their use is second only in frequency to dermatological toxicity. Thus, gastroenterologists can expect to be increasingly frequently consulted by oncologists as part of a multidisciplinary approach to managing toxicity. Here, we describe this novel group of agents and their mechanisms of action. We review the manifestations of gastrointestinal toxicity associated with their use so that it can be recognized early and diagnosed accurately. We also discuss the proposed mechanisms underlying this toxicity and describe an algorithmic and, wherever possible, evidence-based approach to its management.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adachi, K. & Tamada, K. Immune checkpoint blockade opens an avenue of cancer immunotherapy with a potent clinical efficacy. Cancer Sci. 106, 945–950 (2015).

Villadolid, J. & Amin, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 4, 560–575 (2015). This is a comprehensive and clinically useful review of irAEs, which are classified by organ system.

Pardoll, D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 (2012). This is an in-depth Review of checkpoint inhibitors as a potent anticancer treatment.

Lafferty, K. J. & Cunningham, A. J. A new analysis of allogeneic interactions. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 53, 27–42 (1975).

Gmunder, H. & Lesslauer, W. A. 45-kDa human T-cell membrane glycoprotein functions in the regulation of cell proliferative responses. Eur. J. Biochem. 142, 153–160 (1984).

Azuma, M., Cayabyab, M., Buck, D., Phillips, J. H. & Lanier, L. L. CD28 interaction with B7 costimulates primary allogeneic proliferative responses and cytotoxicity mediated by small, resting T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 175, 353–360 (1992).

Schwartz, R. H. A cell culture model for T lymphocyte clonal anergy. Science 248, 1349–1356 (1990).

Brunet, J. F. et al. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily — CTLA-4. Nature 328, 267–270 (1987). This is the first research study describing the discovery of CTLA4.

Chen, L. et al. Costimulation of antitumor immunity by the B7 counterreceptor for the T lymphocyte molecules CD28 and CTLA-4. Cell 71, 1093–1102 (1992).

Krummel, M. F. & Allison, J. P. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 182, 459–465 (1995).

Walunas, T. L. et al. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity 1, 405–413 (1994).

Walunas, T. L., Bakker, C. Y. & Bluestone, J. A. CTLA-4 ligation blocks CD28-dependent T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 183, 2541–2550 (1996).

Linsley, P. S. et al. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J. Exp. Med. 174, 561–569 (1991).

Sakaguchi, S., Yamaguchi, T., Nomura, T. & Ono, M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 133, 775–787 (2008).

Qureshi, O. S. et al. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science 332, 600–603 (2011).

Wing, K. et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science 322, 271–275 (2008). This study identifies the key role CTLA4 has in T reg cell function and homeostasis.

Zheng, Y. et al. Acquisition of suppressive function by activated human CD4+ CD25- T cells is associated with the expression of CTLA-4 not FoxP3. J. Immunol. 181, 1683–1691 (2008).

Fallarino, F. et al. CD40 ligand and CTLA-4 are reciprocally regulated in the Th1 cell proliferative response sustained by CD8(+) dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 169, 1182–1188 (2002).

Sage, P. T., Paterson, A. M., Lovitch, S. B. & Sharpe, A. H. The coinhibitory receptor CTLA-4 controls B cell responses by modulating T follicular helper, T follicular regulatory, and T regulatory cells. Immunity 41, 1026–1039 (2014).

Wang, C. J. et al. CTLA-4 controls follicular helper T-cell differentiation by regulating the strength of CD28 engagement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 524–529 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Structural and functional analysis of the costimulatory receptor programmed death-1. Immunity 20, 337–347 (2004).

Chang, W. S. et al. Cutting edge: Programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 interaction regulates the induction and maintenance of invariant NKT cell anergy. J. Immunol. 181, 6707–6710 (2008).

Liu, J. et al. Immune-checkpoint proteins VISTA and PD-1 nonredundantly regulate murine T-cell responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6682–6687 (2015).

Petrovas, C. et al. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2281–2292 (2006).

Seillet, C. et al. Deciphering the innate lymphoid cell transcriptional program. Cell Rep. 17, 436–447 (2016).

Yu, Y. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies a PD-1hi ILC progenitor and defines its development pathway. Nature 539, 102–106 (2016).

Nishimura, H. & Honjo, T. PD-1: an inhibitory immunoreceptor involved in peripheral tolerance. Trends Immunol. 22, 265–268 (2001).

Terawaki, S. et al. IFN-alpha directly promotes programmed cell death-1 transcription and limits the duration of T cell-mediated immunity. J. Immunol. 186, 2772–2779 (2011).

Nurieva, R. et al. T-Cell tolerance or function is determined by combinatorial costimulatory signals. The EMBO journal 25, 2623–2633 (2006).

Patsoukis, N. et al. PD-1 alters T-cell metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting glycolysis and promoting lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat. Commun. 6, 6692 (2015).

Patsoukis, N. et al. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation. Sci. Signal. 5, ra46 (2012).

Patsoukis, N., Li, L., Sari, D., Petkova, V. & Boussiotis, V. A. PD-1 increases PTEN phosphatase activity while decreasing PTEN protein stability by inhibiting casein kinase 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 3091–3098 (2013).

Taylor, S. et al. PD-1 regulates KLRG1+ group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1663–1678 (2017).

Goldberg, R., Prescott, N., Lord, G. M., MacDonald, T. T. & Powell, N. The unusual suspects — innate lymphoid cells as novel therapeutic targets in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 271–283 (2015).

Tivol, E. A. et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity 3, 541–547 (1995).

Schubert, D. et al. Autosomal dominant immune dysregulation syndrome in humans with CTLA4 mutations. Nat. Med. 20, 1410–1416 (2014).

Bennett, C. L. & Ochs, H. D. IPEX is a unique X-linked syndrome characterized by immune dysfunction, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and a variety of autoimmune phenomena. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 13, 533–538 (2001).

Read, S., Malmstrom, V. & Powrie, F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 192, 295–302 (2000).

Liu, J. Z. et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nature Genet. 47, 979–986 (2015).

Anderson, A. C., Joller, N. & Kuchroo, V. K. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity 44, 989–1004 (2016).

Berman, D. et al. The development of immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies as a new therapeutic modality for cancer: the Bristol-Myers Squibb experience. Pharmacol. Ther. 148, 132–153 (2015).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 711–723 (2010).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00527735 (2012).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01524991 (2017).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00323882 (2014).

Kim, B. J., Jang, H. J., Kim, H. S. & Kim, J. H. Current Status of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Gastrointestinal Cancers. J. Cancer 8, 1460–1465 (2017). This is an up to date review of the potential role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in gastrointestinal cancers, which is of particular interest to gastroenterologists and hepatologists.

Topalian, S. L. et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 1020–1030 (2014).

Brahmer, J. et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 123–135 (2015).

Motzer, R. J. et al. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1430–1437 (2015).

Younes, A. et al. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin's lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17, 1283–1294 (2016).

El-Khoueiry, A. B. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 389, 2492–2502 (2017).

Hamid, O. et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 134–144 (2013).

Reck, M. et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1823–1833 (2016).

Rosenberg, J. E. et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 387, 1909–1920 (2016).

Bristol-Myers Squibb. Ipilimumab U. S. prescribing information: Risk evaluation and mitigation strategy. U.S. Food & Drug Administration https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm249435.pdf (2012).

Fecher, L. A., Agarwala, S. S., Hodi, F. S. & Weber, J. S. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. Oncology 18, 733–743 (2013). This article details the importance of collaborative multidisciplinary care for the optimal recognition and management of irAEs.

Weber, J. S., Kahler, K. C. & Hauschild, A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 2691–2697 (2012).

O'Day, S. J. et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a multicenter single-arm phase II study. Ann. Oncol. 21, 1712–1717 (2010).

Wolchok, J. D. et al. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol. 11, 155–164 (2010).

Blansfield, J. A. et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 blockage can induce autoimmune hypophysitis in patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cancer. J. Immunother. 28, 593–598 (2005).

Byun, D. J., Wolchok, J. D., Rosenberg, L. M. & Girotra, M. Cancer immunotherapy - immune checkpoint blockade and associated endocrinopathies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 13, 195–207 (2017).

Dillard, T., Yedinak, C. G., Alumkal, J. & Fleseriu, M. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy associated autoimmune hypophysitis: serious immune related adverse events across a spectrum of cancer subtypes. Pituitary 13, 29–38 (2010).

Bertrand, A., Kostine, M., Barnetche, T., Truchetet, M. E. & Schaeverbeke, T. Immune related adverse events associated with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 13, 211 (2015).

Yang, J. C. et al. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J. Immunother. 30, 825–830 (2007).

Downey, S. G. et al. Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Res. 13, 6681–6688 (2007).

Beck, K. E. et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 2283–2289 (2006).

Attia, P. et al. Autoimmunity correlates with tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 6043–6053 (2005).

Topalian, S. L. et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2443–2454 (2012).

Weber, J. S. et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 375–384 (2015).

Abdel-Rahman, O. & Fouad, M. Risk of pneumonitis in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 10, 183–193 (2016).

Robert, C. et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 320–330 (2015).

Robert, C. et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet 384, 1109–1117 (2014).

Larkin, J. et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 23–34 (2015).

National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v4.0. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf (2009).

Basch, E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 865–869 (2010).

Fromme, E. K., Eilers, K. M., Mori, M., Hsieh, Y. C. & Beer, T. M. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 22, 3485–3490 (2004).

Pakhomov, S. V., Jacobsen, S. J., Chute, C. G. & Roger, V. L. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am. J. Managed Care 14, 530–539 (2008).

Atkinson, T. M. et al. Reliability of adverse symptom event reporting by clinicians. Qual. Life Res. 21, 1159–1164 (2012).

Basch, E. et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients versus clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J. Natl Cancer Institute 101, 1624–1632 (2009).

Quinten, C. et al. Patient self-reports of symptoms and clinician ratings as predictors of overall cancer survival. J. Natl Cancer Institute 103, 1851–1858 (2011).

[No authors listed.] Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcomes measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. U.S. Food & Drug Administration http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282 (2009).

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. European Medicines Agency http://www.ispor.org/workpaper/emea-hrql-guidance.pdf (2006).

Basch, E. et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute's patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J. Natl Cancer Institute 106, dju244 (2014).

Arnold, B. et al. Linguistic validation of the Spanish version of the National Cancer Institute's Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Support. Care Cancer 24, 2843–2851 (2016).

Baeksted, C. et al. Danish translation and linguistic validation of the U. S. National Cancer Institute's Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). J. Pain Symptom Manage. 52, 292–297 (2016).

Hay, J. L. et al. Cognitive interviewing of the US National Cancer Institute's Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Qual. Life Res. 23, 257–269 (2014).

Kirsch, M. et al. Linguistic and content validation of a German-language PRO-CTCAE-based patient-reported outcomes instrument to evaluate the late effect symptom experience after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 19, 66–74 (2015).

Bennett, A. V. et al. Mode equivalence and acceptability of tablet computer-, interactive voice response system-, and paper-based administration of the U. S. National Cancer Institute's Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 14, 24 (2016).

Dueck, A. C. et al. Validity and Reliability of the US National Cancer Institute's Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol. 1, 1051–1059 (2015).

Hagelstein, V., Ortland, I., Wilmer, A., Mitchell, S. A. & Jaehde, U. Validation of the German patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). Ann. Oncol. 27, 2294–2299 (2016).

Mendoza, T. R. et al. Evaluation of different recall periods for the US National Cancer Institute's PRO-CTCAE. Clin. Trials 14, 255–263 (2017).

Abdel-Rahman, O., ElHalawani, H. & Fouad, M. Risk of gastrointestinal complications in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 7, 1213–1227 (2015).

Robert, C. et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2517–2526 (2011).

Ascierto, P. A. et al. Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg versus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 611–622 (2017).

Jain, A., Lipson, E. J., Sharfman, W. H., Brant, S. R. & Lazarev, M. G. Colonic ulcerations may predict steroid-refractory course in patients with ipilimumab-mediated enterocolitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 23, 2023–2028 (2017).

Marthey, L. et al. Cancer immunotherapy with anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies induces an inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn's Colitis 10, 395–401 (2016).

Mary, J. Y. & Modigliani, R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn's disease: a prospective multicentre study. Gut 30, 983–989 (1989).

Landi, B. et al. Endoscopic monitoring of Crohn's disease treatment: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology 102, 1647–1653 (1992).

Jones, J. et al. Relationships between disease activity and serum and fecal biomarkers in patients with Crohn's disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 1218–1224 (2008).

Modigliani, R. et al. Clinical, biological, and endoscopic picture of attacks of Crohn's disease. Evolution on prednisolone. Gastroenterology 98, 811–818 (1990).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110, 1324–1338 (2015).

Baroudjian, B. et al. Anti-PD1-induced collagenous colitis in a melanoma patient. Melanoma Res. 26, 308–311 (2016).

Garon, E. B. et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2018–2028 (2015).

Rizvi, N. A. et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 257–265 (2015).

Gielisse, E. A. & de Boer, N. K. Ipilimumab in a patient with known Crohn's disease: to give or not to give? J. Crohn's Colitis 8, 1742 (2014).

Fiocchi, C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 115, 182–205 (1998).

Bianchini, F., Kaaks, R. & Vainio, H. Overweight, obesity, and cancer risk. Lancet Oncol. 3, 565–574 (2002).

Sandler, D. P., Wilcox, A. J. & Everson, R. B. Cumulative effects of lifetime passive smoking on cancer risk. Lancet 1, 312–315 (1985).

Clemente, J. C., Ursell, L. K., Parfrey, L. W. & Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 148, 1258–1270 (2012).

Wu, G. D. et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108 (2011).

Montassier, E. et al. Chemotherapy-driven dysbiosis in the intestinal microbiome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 42, 515–528 (2015).

Ungaro, R. et al. Antibiotics associated with increased risk of new-onset Crohn's disease but not ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 1728–1738 (2014).

Hill, G. R. et al. Total body irradiation and acute graft-versus-host disease: the role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood 90, 3204–3213 (1997).

Naidu, M. U. et al. Chemotherapy-induced and/or radiation therapy-induced oral mucositis — complicating the treatment of cancer. Neoplasia 6, 423–431 (2004).

Hsieh, A. H., Ferman, M., Brown, M. P. & Andrews, J. M. Vedolizumab: a novel treatment for ipilimumab-induced colitis. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-216641 (2016).

Bergqvist, V. et al. Vedolizumab treatment for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 66, 581–592 (2017). This is the first and (at the time of writing) only case series to describe the effectiveness of vedolizumab for treating the enterocolitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Berman, D. et al. Blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 by ipilimumab results in dysregulation of gastrointestinal immunity in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Immun. 10, 11 (2010).

Shahabi, V. et al. Gene expression profiling of whole blood in ipilimumab-treated patients for identification of potential biomarkers of immune-related gastrointestinal adverse events. J. Transl Med. 11, 75 (2013).

Dubin, K. et al. Intestinal microbiome analyses identify melanoma patients at risk for checkpoint-blockade-induced colitis. Nat. Commun. 7, 10391 (2016).

Marshall, J. C., Christou, N. V. & Meakins, J. L. Small-bowel bacterial overgrowth and systemic immunosuppression in experimental peritonitis. Surgery 104, 404–411 (1988).

Aggarwal, V., Williams, M. D. & Beath, S. V. Gastrointestinal problems in the immunosuppressed patient. Arch. Dis. Child 78, 5–8 (1998).

Stacey, R. & Green, J. T. Radiation-induced small bowel disease: latest developments and clinical guidance. Ther. Adv. Chron. Dis. 5, 15–29 (2014).

Andreyev, H. J. et al. Practice guidance on the management of acute and chronic gastrointestinal problems arising as a result of treatment for cancer. Gut 61, 179–192 (2012).

Abdel-Wahab, N., Shah, M. & Suarez-Almazor, M. E. Adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade in patients with cancer: a systematic review of case reports. PloS ONE 11, e0160221 (2016).

Gentile, N. M., D'Souza, A., Fujii, L. L., Wu, T. T. & Murray, J. A. Association between ipilimumab and celiac disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 88, 414–417 (2013).

Weber, J. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 5591–5598 (2009).

Mowat, C. et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 60, 571–607 (2011).

Walley, T. & Milson, D. Loperamide related toxic megacolon in Clostridium difficile colitis. Postgrad. Med. J. 66, 582 (1990).

Brown, J. W. Toxic megacolon associated with loperamide therapy. JAMA 241, 501–502 (1979).

Khalil, J. et al. Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: an underestimated major health problem. World J. Surg. Oncol. 13, 204 (2015).

Bernstein, C. N., Blanchard, J. F., Houston, D. S. & Wajda, A. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Thromb. Haemost. 85, 430–434 (2001).

Andreyev, J. et al. Guidance on the management of diarrhoea during cancer chemotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 15, e447–460 (2014).

Horvat, T. Z. et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3193–3198 (2015). This study reports on a moderately large series of patients with colitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors who were treated with infliximab, as well as a single patient treated with adalimumab.

O'Connor, A., Marples, M., Mulatero, C., Hamlin, J. & Ford, A. C. Ipilimumab-induced colitis: experience from a tertiary referral center. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 9, 457–462 (2016).

Verschuren, E. C. et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic characteristics of ipilimumab-associated colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 836–842 (2016).

Hillock, N. T., Heard, S., Kichenadasse, G., Hill, C. L. & Andrews, J. Infliximab for ipilimumab-induced colitis: a series of 13 patients. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 13, e284–e290 (2017).

Lankes, K. et al. Anti-TNF-refractory colitis after checkpoint inhibitor therapy: possible role of CMV-mediated immunopathogenesis. Oncoimmunology 5, e1128611 (2016).

Spain, L., Diem, S. & Larkin, J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treatment Rev. 44, 51–60 (2016).

Mitchell, K. A., Kluger, H., Sznol, M. & Hartman, D. J. Ipilimumab-induced perforating colitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 47, 781–785 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to discussion of content and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submissions. M.A.S. and P.P. researched the contributing data and wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.A.S. has received advisory fees from Hospira and lecture fees from Falk, Hospira, Janssen, MSD and Takeda. S.P. has received advisory fees from Amgen, MSD and Roche and lectures fees from Bristol–Myers Squibb and MSD. N.P. has received advisory fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Debiopharm International, Ferring and Vifor Pharma and lectures fees from Allergan, Falk, Janssen, Tillotts and Takeda. P.M.I. has received advisory fees from AbbVie, Genentech, Hospira, Janssen, MSD, Pharmacosmos, Samsung Bioepis, VH2, Vifor Pharma, Takeda, Topivert and Warner Chilcott, lecture fees from AbbVie, Falk, Ferring and Warner Chilcott and financial support for research from MSD and Takeda. P.P. declares no competing interests.

Related links

Glossary

- Antigen-presenting cells

-

(APCs). Cells that capture, process and display antigens (such as those from microorganisms, environmental toxins and/or tumour neo-antigens) to lymphocytes; they also express co-stimulatory signals (that is, CD80/CD86 expression), which are necessary for lymphocyte activation (proliferation and effector function).

- Tolerance

-

A state in which the adaptive immune system does not respond to an antigen. During T cell development in the thymus, cells that recognize self-antigens are deleted (central tolerance), a process that contributes to self-tolerance, a homeostatic attribute of the adaptive immune system.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors

-

Drugs that promote an antitumour immune response by blocking signalling via either the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) pathway or the programmed cell death 1 (PD1) pathway.

- Co-stimulatory pathway

-

The necessary, additional activating signal to T cell receptor (CD3) engagement with antigen, which leads T cells towards proliferation and effector function.

- Immunological synapse

-

The crosstalk interface for immune cells where, for example, the antigen presented by an antigen-presenting cell and its surface CD80 molecule engage a T cell through the T cell receptor and CD28, respectively.

- Regulatory T cells

-

(Treg cells). Regulatory cells, usually defined as CD4+CD25+, that are characterized by the expression of the transcription factor forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3). Through cytokine production (such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ)) and cellular interactions (that is, through cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4)), they suppress the responses of surrounding activated lymphocytes.

- CD4+ T effector cells

-

T cells that, upon activation by an antigen-presenting cell, produce cytokines and drive inflammation. Activated naive cells turn to memory cells that can mount a response to the same antigen much more quickly.

- Hypophysitis

-

An acute or chronic inflammation of the pituitary gland.

- Patient-reported outcomes

-

(PROs). Health outcomes directly reported by the patients who experience them.

- Acute abdomen

-

A rapid onset of severe symptoms that can indicate potentially life-threatening intra-abdominal pathology that requires urgent surgical intervention.

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

-

The presence of excessive bacteria in the small intestine, frequently implicated as the cause of chronic diarrhoea and malabsorption.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samaan, M., Pavlidis, P., Papa, S. et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: from mechanisms to management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 15, 222–234 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2018.14

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2018.14

This article is cited by

-

Immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies: achievements, challenges and future prospects

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2023)

-

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Rechallenge After Prior Immune Toxicity

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2022)

-

Nivolumab dose escalation triggered immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis after 147 weeks of prolonged stable use in a patient with lung cancer: a case report

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2022)

-

The FOCCUS study: a prospective evaluation of the frequency, severity and treatable causes of gastrointestinal symptoms during and after chemotherapy

Supportive Care in Cancer (2021)

-

The role of T cell trafficking in CTLA-4 blockade-induced gut immunopathology

BMC Biology (2020)