Key Points

-

Host-directed therapy (HDT) is a novel approach in the field of anti-infectives for overcoming antimicrobial resistance.

-

HDT aims to interfere with host cell factors that are required by a pathogen for replication or persistence, to enhance protective immune responses against a pathogen, to reduce exacerbated inflammation and to balance immune reactivity at sites of pathology.

-

HDTs encompassing the 'shock and kill' strategy or the delivery of recombinant interferons are possible approaches to treat HIV infections. HDTs that suppress the cytokine storm that is induced by some acute viral infections represent a promising concept.

-

In tuberculosis, HDT aims to enhance the antimicrobial activities of phagocytes through phagosomal maturation, autophagy and antimicrobial peptides. HDTs also curtail inflammation through interference with soluble (such as eicosanoids or cytokines) or cellular (co-stimulatory molecules) factors and modulate granulomas to allow the access of antimicrobials or to restrict tissue damage.

-

Numerous parallels between the immunological abnormalities that occur in sepsis and cancer indicate that the HDTs that are effective in oncology may also hold promise in sepsis.

-

Advances in immune phenotyping, genetic screening and biosignatures will help to guide drug therapy to optimize the host response. Combinations of canonical pathogen-directed drugs and novel HDTs will become indispensable in treating emerging infections and diseases caused by drug-resistant pathogens.

Abstract

Despite the recent increase in the development of antivirals and antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance and the lack of broad-spectrum virus-targeting drugs are still important issues and additional alternative approaches to treat infectious diseases are urgently needed. Host-directed therapy (HDT) is an emerging approach in the field of anti-infectives. The strategy behind HDT is to interfere with host cell factors that are required by a pathogen for replication or persistence, to enhance protective immune responses against a pathogen, to reduce exacerbated inflammation and to balance immune reactivity at sites of pathology. Although HDTs encompassing interferons are well established for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis, novel strategies aimed at the functional cure of persistent viral infections and the development of broad-spectrum antivirals against emerging viruses seem to be crucial. In chronic bacterial infections, such as tuberculosis, HDT strategies aim to enhance the antimicrobial activities of phagocytes and to curtail inflammation through interference with soluble factors (such as eicosanoids and cytokines) or cellular factors (such as co-stimulatory molecules). This Review describes current progress in the development of HDTs for viral and bacterial infections, including sepsis, and the challenges in bringing these new approaches to the clinic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Infectious diseases that are caused by bacterial and viral pathogens remain a major global health threat. Antibiotics have contributed to a profound reduction in disease incidence caused by bacterial pathogens, but we increasingly face antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to these antibiotics, and the development of new antibacterials lags behind the emergence of resistance. In 2015, an estimated 700,000 deaths were caused by pathogens with antimicrobial resistance1. The steep growth in research and development (R&D) for new antibiotics between 1950 and 1980 resulted in approximately 200 new drugs on the market. However, only 12 new antibiotics have been licensed in the 21st century.

Persistent viral infections can only rarely be cured, and major epidemics and pandemics such as those caused by the Ebola virus or Zika virus underscore our need for broadly active antivirals. Moreover, available antivirals are often limited by the rapid emergence of drug resistance. Approximately 90 new antiviral drugs have been approved in the past 50 years, and 29 of these have been approved in the past 6 years, mostly for the selective treatment of infections with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV2. There is a clear rise in R&D of antiviral drugs, but in contrast to antibiotics, their activity spectrum is mostly limited to a distinct virus group. For many viruses, particularly those that are highly prevalent in developing countries — including hepatitis and flaviviruses — such drugs are not available. Moreover, the constant emergence of infections with new virus species and the increasing incidences of outbreaks of viral diseases with pandemic potential emphasize the need for broad-spectrum antiviral drugs.

Undoubtedly, R&D for canonical antimicrobials that directly target pathogens must continue, but additional approaches are also urgently needed. One such complementing strategy is host-directed therapy (HDT) with biologics or small molecules. HDT can: interfere with host mechanisms that are required by a pathogen for productive replication or persistence; enhance the immune response by stimulating mechanisms that are involved in host defence against the pathogen; target pathways that are perturbed by a pathogen and contribute to hyper-inflammation; and modulate host factors that lead to dysbalanced responses at the site of pathology. In the case of targeting hyper-inflammation and dysbalanced responses, treatment is symptomatic rather than causal, but reduces exacerbated tissue damage in infectious diseases and confines microbial niches. Accordingly, HDT for infectious diseases shares similarities with conventional therapy of non-communicable diseases. Indeed, several HDT approaches rely on the repurposing of licensed drugs for other diseases, such as cancer, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. However, in the area of infectious diseases, anti-infectives that directly target the pathogen have been generally considered as the only treatment option. Therefore, the concept of HDT for infectious diseases, although not novel in the strictest sense, provides untapped opportunities that are urgently needed in the face of increasing AMR.

HDT-based approaches are less prone to therapy resistance than anti-infectives that directly target pathogens, because resistance would require the pathogen to use an alternative host factor to replicate, to become less dependent on the targeted host factor or to evade activated host defence mechanisms. Principally, these host factors are evolutionarily conserved, and therefore, successful evasion requires considerable mutational changes in the pathogen. Nevertheless, most HDT approaches are not considered to be stand-alone therapies but are combined with canonical anti-infectives. In this Review, we compare different HDT approaches for viral and bacterial infections and describe the progress made in their development, focusing mostly on tuberculosis (TB) (Box 1) and sepsis for bacterial infections and on chronic viral hepatitis and AIDS for viral infections (Table 1). We also provide deeper insights into the general principles underlying different diseases and note commonalities and differences between HDTs for distinct infections. Owing to space limitations and recently published reviews on the topic3,4, prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines are not covered here and only a few examples are mentioned (Supplementary information S1 (table)).

Interfering with host cell mechanisms

All viruses and some bacteria are intracellular parasites and as such require host cells for their replication and persistence. On the one hand, host cells provide, among other mechanisms, the synthetic machinery and energy source. On the other hand, host cells have intrinsic defence mechanisms that are triggered by infection. Therefore, viruses and bacteria must possess strategies to block such defences. Taking advantage of our increasing knowledge of pathogen–host cell interaction, novel strategies for HDTs are currently being pursued that either block host cell factors or pathways essential for pathogen survival, or activate and reinstall pathogen-antagonizing mechanisms, thus rendering the host cell non-permissive.

Inhibiting productive viral replication

Viral infection begins with the attachment of the virion to the host cell, a process that requires specific interactions between proteins that are exposed on the surface of the virus particle and one or several receptors on the plasma membrane of the host cell (Fig. 1). This interaction triggers the entry of the virus particle into the cell, the dissociation of the nucleocapsid and ultimately, the release of the viral genome, to be used for reverse transcription and integration (in the case of HIV) or RNA synthesis (for example, for hepatitis B virus (HBV)) or directly for protein production (such as for HCV) (Fig. 1). Viral proteins, together with host cell factors, catalyse the amplification of the viral genome, which is packaged into progeny virions. These are released from the cell to initiate a new round of infection.

a I Upon entry of hepatitis C virus (HCV) into the cell, viral RNA is translated at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and a membranous replication factory is formed (a membranous web). There, viral RNA (vRNA) is amplified and packaged into nucleocapsids that bud into the ER. Enveloped virions are secreted out of the cell. b I In the case of HBV, upon virus entry, the partially double-stranded viral DNA genome is converted into the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) form that persists as an episome in the nucleus. vRNAs are transcribed and used for protein synthesis. Within the nucleocapsids the vRNA pre-genome is reverse transcribed by the viral polymerase (red circle) and virions are formed by budding into the ER lumen. Virions are secreted from the cell, along with subviral particles (SVPs) that lack a nucleocapsid and so are non-infectious. SVPs are composed of the same envelope (Env) proteins as infectious HBV particles. c I HIV enters upon interaction with the CD4 receptor and a co-receptor (such as CCR5) by direct fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane. Nucleocapsids that contain the RNA genome are released into the cytoplasm and upon reverse transcription a pre-integration complex (PIC) containing the viral integrase (green bar) is formed. The viral DNA genome (blue) is inserted into the host cell genome (light purple) and this provirus serves as a template for the transcription of all viral mRNAs (vRNAs). These are translated in the cytoplasm and give rise to HIV proteins; some of them (the Gag and Gag–Pol polyprotein precursors) are transported to the plasma membrane to trigger the formation of nucleocapsids. These nucleocapsids acquire their envelope by budding at the plasma membrane. The viral polyproteins are cleaved within the released virions, thus inducing a rearrangement of the structural proteins, visible by morphological conversion into a conical nucleocapsid. Only these particles are infectious. CypA, cyclophilin A; HBIGs, hepatitis B immunoglobulins; HDT, host-directed therapy; ISGs, interferon-stimulated genes; TCR, T cell receptor.

As viruses require host cell factors for nearly every step of their life cycle, each required host dependency factor (HDF) is a potential drug target. Ideally, a moderate reduction in HDF abundance or its availability would already substantially impair virus production and the HDF would be non-essential for host cell survival, which would reduce the likelihood of cytotoxicity. Accordingly, inhibitors that target the very early stages of viral replication and block the binding of the virus particle to the host cell receptor have emerged as a promising approach (Supplementary information S1 (table)).

Entry inhibitors for HIV-1. Regarding entry inhibitors, during the past two decades, most progress has been made in the treatment of infections with HIV type 1 (HIV-1). Entry of this virus requires the interaction between the primary receptor CD4 and one of two chemokine receptors that act as co-receptors: CXC-chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4; X4) and CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5; R5)5 (Fig. 1). Whereas CXCR4 is expressed on T cells and promotes the entry of T cell-tropic HIV-1 (X4-strains), CCR5 is expressed on macrophages and some populations of T cells and promotes the entry of macrophage-tropic HIV-1 (R5 strains). Intriguingly, individuals with certain mutations in CCR5 are resistant to infection with R5 strains, which predominate during the early stages of infection, whereas X4-tropic strains emerge during the later stages of infection6 — thus qualifying CCR5 as an attractive target for HDTs6. Antagonists of CCR5 have been developed7 that lock the receptor into a non- permissive conformation and thereby dampen its co-receptor function. This concept, which was originally established in vitro, has been translated into clinical use, and Maraviroc (Selzentry/Celsentri; Pfizer) was approved as a first-in-class CCR5 inhibitor in 2007. As expected for an HDT, resistance to Maraviroc is low, and given the importance of CCR5 in HIV infection Maraviroc has become a component of HIV-1 therapy8. Apart from its virological benefit, Maraviroc has also been found to increase the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in some patients, suggesting that it has an additional immunological benefit8. The underlying mechanisms are unclear but could be due to the involvement of CCR5 in immune regulation. However, the clinical use of Maraviroc is limited given its restriction to R5-tropic viruses. Precise HIV typing can delay the onset of treatment and can cause therapy failure when virus tropism changes in the patient. Accordingly, companion diagnosis and individualized treatments are required for this and other selected HDTs.

Entry inhibitors for hepatitis viruses. Another example of an entry inhibitor is the investigational agent myrcludex B, which is a peptide derived from the large surface glycoprotein of HBV (Supplementary information S1 (table)). This peptide binds to the cell surface molecule sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP), which is required for productive HBV infection9,10, and blocks viral entry with extremely high potency (IC50 of approximately 80 pM)11 (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, the same entry receptor is also exploited by hepatitis D virus (HDV) — a satellite virus that requires the surface glycoproteins of HBV for virus particle formation (reviewed in Ref. 12). Thus, HDV is consistently associated with HBV, and this co-infection is responsible for the most severe form of virally induced liver disease. Because of this peculiar biology, myrcludex B also blocks the entry of HDV9. The IC50 values of myrcludex B for HBV and HDV entry inhibition are comparable and more than 500-fold lower than the IC50 of bile salt transport inhibition, suggesting that virus entry can be blocked at doses with minor effects on the physiological function of NTCP. Encouraged by these results, clinical trials have been conducted and have demonstrated the excellent tolerability of even high doses of myrcludex B13. Moreover, a phase Ib/IIa clinical trial of myrcludex B as a monotherapy in patients with chronic HBV–HDV co-infection revealed a strong reduction of HDV RNA serum levels and the normalization of liver enzymes (markers of liver cell damage). There was also a synergistic antiviral effect on HDV and HBV levels in patients treated with a combination of myrcludex B and polyethylene glycol-conjugated (pegylated) interferon α2a (PegIFNα2a)14. Myrcludex B received orphan drug status from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and further clinical trials are ongoing.

Myrcludex B and Maraviroc illustrate how entry inhibition is a promising target for HDTs and support the broad applicability of such an HDT strategy. The recent identification of entry molecules, such as NPC1 for Ebola virus, LAMP1 for Lassa virus and PLA2G16 for picornaviruses, provides an ideal starting point for the development of HDTs against these threatening pathogens.

Targeting the HDFs required for HCV replication. Apart from targeting entry receptors, HDFs that are required for viral replication are equally attractive drug targets. One example is the host cell chaperone cyclophilin A (CypA). By using replicon-based assays, it was found that the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine A (CsA) potently inhibits HCV replication15 by binding to and thereby sequestering CypA. Subsequent studies identified CypA as the primary HDF that promotes HCV replication16,17. As CypA is likely to be required for the proper assembly and activity of the HCV replicase complex, its sequestration renders the replicase inactive18. However, the CypA–CsA complex inhibits the protein phosphatase calcineurin, which is required for T cell activation, thus causing an immunosuppressive effect. Therefore, non-immunosuppressive Cyp antagonists, which are mostly derived from CsA, have been designed, including alisporivir (previously known as Debio 025), NIM811 and SCY-635. Although phase I and phase II clinical trials conducted with alisporivir and SCY-635 have demonstrated the inhibition of HCV across different genotypes and a high genetic barrier to resistance19,20, further clinical development of these compounds was not pursued, presumably due to the very rapid development of direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) for HCV. However, CypA is a host cell factor used by viruses from different families, such as coronaviruses21 and HIV22, suggesting that CypA antagonists have the potential to be developed into broad-spectrum antivirals. Although natural pre-existing mutations in the HIV capsid protein, the CypA interaction partner, would limit the broad clinical use of this compound class, CypA-knockout mice and human cells are fully viable23,24, and therefore possible toxicity associated with CypA inhibition should be low.

Another example of an HDF that promotes viral replication is microRNA-122 (miR-122). This miRNA is preferentially expressed in hepatocytes, the primary host cells of HCV, and regulates lipid metabolism, but also binds to several regions of the HCV genome, most notably two regions close to the 5′ end, and stimulates RNA replication25. Soon after the discovery of miR-122 as an HDF of HCV, antisense-based oligonucleotide approaches (known as antagomirs) were developed to sequester miR-122 in infected cells, thereby blunting HCV replication. This approach was well tolerated both in vitro and in vivo and imposed a high genetic barrier to resistance26,27. However, studies with miR-122-knockout mice identified this miRNA as a tumour suppressor28,29, which raised concerns about its inhibition. Moreover, given the challenges in the delivery of miR-122-specific antagomirs, to the best of our knowledge only one clinical candidate, RG-101 (Regulus Therapeutics) which is an N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated oligonucleotide that antagonizes miR-122 and that is targeted to hepatocytes, is being pursued in combination with different approved or investigational DAAs30.

Rectifying antibacterial cellular defence

Owing to the higher autonomy of bacteria compared with viruses, targeting host cell pathways, rather than individual factors, is a more frequent HDT approach in bacterial infections (Box 1; Supplementary information S2 (table)). The causative agent of TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), persists in macrophages by subverting multiple intracellular antimicrobial mechanisms. Mtb replicates within early phagosomes, prevents fusion with lysosomes, counteracts acidification and escapes into the host cytosol. It inhibits host cell apoptosis and autophagy and causes host cell lysis31. Consequently, Mtb replicates in macrophages and even induces their transformation into epithelioid and giant cells, as well as into foamy cells that are rich in cholesterol stored in lipid bodies, which are an important carbon source for Mtb.

Adjusting autophagy and phagosomal killing in TB. The most prominent cell-intrinsic biological pathway within macrophages targeted by numerous HDT candidates is autophagy, which is used as a host defence strategy against numerous bacterial pathogens32. Soluble mediators that are essential for host defence against Mtb — including interferon-γ (IFNγ), the main activator of macrophages (Box 2) — stimulate autophagy33. Mtb inhibits autophagy by means of lipids (such as mannose capped lipoarabinomannan (ManLAM), lipid C)34, early secretory antigenic target-6 ESX1 secretion system products35,36 and mycobacterial virulence factors encoded in the eis gene region37,38. To overcome Mtb resistance to killing by macrophages and to promote Mtb entry into autophagic compartments, a diverse range of pro-autophagic drugs has been proposed for TB management by HDT. These compounds comprise small molecules that belong to several pharmacological groups (Fig. 2; Supplementary information S2 (table)), many of which are approved for diverse indications, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disorders and hypertension.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is phagocytosed by macrophages and interferes with endosomal maturation. Bacilli block the fusion of the phagosome with lysosomes, egress into the cytosol, restrict autophagy and induce the accumulation of lipid bodies. The anti-mycobacterial activity of the macrophage is enhanced by stimulation with cytokines, as well as with factors that promote the secretion of antimicrobial peptides, such as vitamins. Several host-directed therapies (HDTs) have been directed at each stage of the macrophage life cycle of Mtb to overcome resistance to microbial killing. Each box indicates drugs or classes of drugs with proven effects on antimicrobial immunity. HDAC, histone deacetylase; IFNγ, interferon-γ; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PDE, phosphodiesterase; TB, tuberculosis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Despite being highly amenable to targeting by small compounds, only a few autophagy inducers are currently ready for clinical trials. On the one hand, this is due to the limited availability of the detailed pharmacokinetics of such drugs; on the other hand, it relates to their preclinical testing in TB. The best studied autophagy inducer is rapamycin (sirolimus)39, which reduces the replication of Mtb in macrophages33,40. However, rapamycin also causes profound immune suppression and is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4, which is strongly induced by the anti-TB drug rifampin (also known as rifampicin). This warrants caution for the use of rapamycin in combination with rifampin. Moreover, the reactivation of latent TB infection (LTBI) upon rapamycin therapy argues against prioritizing it as an HDT41,42.

Various screens with Mtb-infected macrophages have also identified anticonvulsants (carbamazepine and valproate), selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (fluoxetine) and epidermal growth factor inhibitors (gefitinib) as autophagy inducers that affect Mtb replication43,44. The calcium channel blocker verapamil also induces autophagy and has proved efficacious as an adjunct to TB chemotherapy, notably delivered in combination with the first-line drug rifampin or with the newly developed anti-TB diarylquinoline bedaquiline in a mouse model, but only at a dose that is toxic for humans45,46. Currently, the most promising drug that induces autophagy and promotes phagosome maturation of Mtb-infected cells is the oral biguanide metformin, which is widely used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Metformin activates 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and interferes with the mitochondrial respiratory chain, promoting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent Mtb killing in human and murine macrophages. To a certain extent, metformin restricts bacillary growth in murine pulmonary TB47. Given its widespread application and acceptable safety profile, metformin seems to be ready to enter clinical trials as an HDT for TB48.

Other drugs that may overcome the inhibition of phagosome maturation in Mtb-infected macrophages are tyrosine kinase inhibitors and cholesterol-lowering agents. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target the fusion protein BCR–ABL — such as imatinib, which restricts Mtb replication — arrest proliferation and restore apoptosis in myeloid cells and have been approved for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia49,50. Statins (such as lovastatin, simvastatin and atorvastatin, which inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme reductase (HMG-CoA), the rate-limiting enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway), are commonly indicated for patients suffering from vascular disorders. Besides phagosomal maturation, statins trigger autophagy in Mtb-infected macrophages. They also limit lipid body biogenesis, thereby restricting the generation of foamy cells, which support Mtb persistence51. These statin-induced effects lead to the killing of intracellular Mtb in macrophages in vitro and in vivo in experimental mouse models52,53,54. Treatment with simvastatin in combination with canonical drugs, such as isoniazid, rifampin and pyrazinamide, shortens therapy duration in murine TB55. Moreover, a retrospective investigation in a large patient cohort that comprised more than 8,000 new TB cases and 800,000 control patients revealed that there is no risk of TB reactivation upon statin intake56. This study was prompted by epidemiological observations that statins improve the clinical outcome of respiratory infections. Because of their widespread use and good safety profile, statins remain attractive HDT candidates for TB.

Enhancing the immune response

The approaches to HDT described above have focused on enhancing cell-intrinsic antimicrobial mechanisms with the aim of controlling and ideally clearing infection. Several approaches have also been pursued to target either the innate (Box 2) or the adaptive immune response for both viral and bacterial infections.

Viral infections

Until the first approvals of IFN-free DAA-based therapy for chronic hepatitis C in late 2014 and early 2015, IFN therapy was primarily used for the treatment of patients infected with HCV and, in countries unable to afford the high-cost DAA treatment, it is still in use for this purpose54. Cells treated with this cytokine mount an antiviral state and thus are protected against viral infection, but IFN simultaneously has important stimulatory effects on the adaptive immune response. In addition, new strategies are currently emerging based on the use of individualized engineered T cells, which are designed to break persistent virus infections.

Activating immunity by exogenous IFN in HCV, HBV and HIV. Several recombinant IFNs have been licensed for the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C (Supplementary information S1 (table)). These include IFN alfacon-1, a recombinant and synthetic type I IFN, recombinant IFNα2a (Roferon-A) and IFNα2b (Intron A), which must be administered by subcutaneous injection several times a week, as well as PegIFNα2a (Pegasys) and PegIFNα2b (PegIntron), which are injected once a week.

The success of therapy, as measured by the sustained virological response (SVR), is considerably increased when PegIFN is combined with ribavirin, primarily owing to the prevention of virus relapse when therapy is terminated57. Multiple parameters affect SVR rates, including high body mass index, liver cirrhosis and the genotype of the infecting HCV58. In addition, polymorphisms in the gene encoding one of the type III IFNs, IFNλ3 (IFNL3; also known as IL28B), are highly predictive for the outcome of therapy, as well as acute infection54, but the underlying reasons are not clearly defined59.

Major limitations of IFN-based therapy are the numerous side effects, which include influenza-like symptoms with fever and fatigue, depression, bone marrow suppression, exacerbated autoimmunity and, mainly due to ribavirin, haemolytic anaemia. These side effects were particularly pronounced with IFN alfacon-1, which was discontinued in 2013. With the aim of reducing these systemic effects, clinical trials have been conducted with PegIFNλ1a because the expression of the receptor for this IFN is limited to the mucosal epithelial cells and the human liver60. However, SVR rates of patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with PegIFNλ1a or PegIFNα2a were similar, although extrahepatic adverse events were less frequent in patients treated with PegIFNλ1a61. Given the comparable efficacy of type III and type I IFN, and presumably also due to the rapid development of IFN-free treatment modalities, further clinical development of PegIFNλ1a for chronic hepatitis C has not been pursued.

PegIFNα2a has also been approved for the treatment of adults chronically infected with HBV, but not for children62,63. However, disappointingly low SVR rates have been achieved — defined as the loss of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) with or without the production of HBsAg-specific antibodies (referred to as HBsAg seroconversion), the sustained control of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) in the liver (Fig. 1) and non-detectable viral DNA in the serum64,65. Although the combination of PegIFNα2a with an HBV-specific nucleoside analogue enhances SVR rates, the overall response is still below 10%64 and seems to depend on the chosen nucleoside analogue66,67. Despite these drawbacks, PegIFNα2a has certain advantages over currently available chemotherapy, notably the lack of drug resistance (which is a major concern, especially with lamivudine), a finite treatment course (usually 24–48 weeks) and the induction of a more durable virological response (particularly HbsAg seroconversion).

IFNα has also been shown to have antiviral activity against HIV-1 (Ref. 68). However, this area of research has been somewhat neglected, and the role of IFNs in controlling HIV infection has only recently received increasing attention69. For example, the administration of IFNα2a in the rhesus macaque model before and after infection with a pathogenic strain of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) prevented systemic infection, but continued IFNα2a treatment dampened the host IFN response, concomitant with reduced antiviral gene expression70. In addition, blocking the type I IFN receptor reduced antiviral gene expression, enhanced SIV replication, and spread and accelerated CD4+IFNλ1aT cell loss70. Interestingly, a phase II clinical trial of PegIFNα2a in patients infected with HIV-1 revealed a significant, albeit moderate, reduction of plasma viral load after 12 weeks of treatment71. These observations suggest that the administration of supraphysiological levels of IFN to patients infected with HIV-1 can help to control virus replication. However, HIV-1 has developed numerous strategies to avoid detection by pattern recognition receptors and to block IFN-induced restriction factors, thus limiting the anti-HIV activity of IFNα69. Moreover, increased IFNα activity seems to contribute to immune activation and immune dysfunction in HIV-positive patients. Therefore, dampening IFNα production, although it may have detrimental effects on suppressing HIV replication, might reduce immune activation and thus the severity of disease.

Activating the endogenous innate immune response via TLRs. Various approaches have been developed to boost the endogenous innate (IFN) response, most of them relying on the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs). One TLR agonist approved for antiviral therapy is the imidazoquinoline imiquimod. Imiquimod is given topically in a cream formulation for the local treatment of external genital and perianal warts, which are frequently caused by infections with human papillomaviruses (HPVs). Imiquimod is sensed by TLR7 and triggers the production of various cytokines, most notably IFNα, IL-1, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)72, and causes a reduction in viral load and wart size73. In addition, imiquimod activates Langerhans cells, which migrate to local lymph nodes to promote the adaptive immune response74. Treatment duration is a maximum of 16 weeks, with clearance rates of up to 50% and a recurrence rate of 13%75.

Enhancing cellular immunity in HIV-1 infection. A major challenge to the successful control of HIV infection is the persistence of proviral (integrated) DNA in resting CD4+ T cells (latency reservoir) (Fig. 1) and the pronounced immune suppression that results from infection. Different strategies are currently being pursued to tackle these challenges, including a 'shock and kill' approach, in which latent HIV-1 is reactivated in T cells to allow the killing of these cells through immune effector functions76. One example is the stimulation of the RIG-I pathway by the approved retinoic acid derivative acitretin. This treatment activates HIV transcription and RIG-I expression, which in turn senses HIV RNA, thus mounting an IFN response and preferentially inducing the apoptosis of HIV-infected cells77. Although early clinical studies with drugs such as acitretin that trigger the transcription of the proviral genome have raised hopes that this strategy can be used to reverse HIV-1 latency, the extent to which this strategy can reduce the viral reservoir size remains to be determined.

Hopes of achieving HIV eradication by immune-based therapies have been reactivated by the famous Berlin patient78; however, aiming for a 'functional cure' — that is, the immune control of HIV without eradication — seems to be more realistic. One approach is the use of immune cells that are engineered to express molecularly cloned T cell receptors that recognize HIV epitopes. However, this approach is limited because many of the most highly effective CD8+ T cells that have been identified in patients recognize HIV epitopes in the context of uncommon human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles and are therefore not applicable to the majority of infected individuals with common HLA alleles79. Moreover, owing to high levels of HIV genomic variability, particularly in patients with long-term infection, most latent HIV infections comprise escape mutants that are not targeted by T cell receptors80.

Some of these limitations can be overcome by using T cells that express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) (reviewed in Ref. 81). However, despite promising in vitro and in vivo results, the clinical value of these approaches for HIV-infected individuals remains to be determined.

Activating immunity by the release of immune suppression in HCV, HBV and HIV. Chronic hepatitis B leads to the exhaustion of T cells by inducing increased expression of the checkpoint inhibitors programmed cell death 1 (PD1) and its ligand (PDL1) on immune effector cells. In a mouse model of hepatitis B, therapy with anti-PD1 antibody increased HBcAg-specific interferon gamma (IFNγ) production by intrahepatic T cells, reversed the exhausted T cell phenotype, and led to the clearance of HBV82. The potential efficacy of checkpoint blockade with anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1 in hepatitis B is underscored by additional studies showing that anti-PD1 is effective in other chronic viral infections: for example, the treatment of HCV-infected chimps with an anti-PD1 antibody enhanced antiviral T cell responses and reduced viraemia83. Similarly, the treatment of SIV-infected macaques with anti-PD1 antibody led to significant reductions in plasma viral load and prolonged survival84.

Bacterial infections

The antimicrobial capacities of macrophages can be enhanced by activation with cytokines, vitamins or other factors that stimulate cell autonomous responses or that drive the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) (Fig. 2; Supplementary information S2 (table)). Immune-enhancing strategies usually exert pleiotropic effects by integrating the stimulation of antimicrobial immunity and the rectification of pathways that are blocked or altered by Mtb. Besides macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils also harbour Mtb, however, no HDT approaches targeting these cells have so far been envisaged.

Activating myeloid cells with vitamins in TB. Mixed effects on macrophages have been reported for vitamin A and vitamin D85,86. Mechanistically, vitamin D3 induces the AMP cathelicidine87, triggers ROS production and promotes autophagy in infected macrophages88. AMP induction is potentiated by the co-administration of histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as phenylbutyrate89,90 (Fig. 2). Although previous clinical trials assessing the benefits of vitamin D3 in TB have provided inconclusive results90,91,92,93,94, several trials with vitamin D as an adjunct to TB chemotherapy, notably first-line drugs, are ongoing95,96. The microbicidal effects of vitamin A have been recognized for decades97, and have been attributed to direct effects on Mtb98,99, as well as to the modulation of host immunity. Vitamin A derivatives, notably all-trans retinoic acid, restrict Mtb growth in macrophages by inducing phagosomal acidification100. In rats and mice, all-trans retinoic acid reduces Mtb loads101,102 by modulating cellular immunity and inflammation, but supplementation with vitamin A has not shown any beneficial outcome in patients103,104. The careful selection of the minimal effective dosage of these vitamins may form the basis for HDT in TB.

Cytokine-mediated activation of myeloid cells in TB. Several cytokines, notably TNF, IFNγ and IL-1, stimulate antimicrobial activities in macrophages (Fig. 2). IFNγ promotes phagosome maturation and autophagy, TNF augments responsiveness to IFNγ and upregulates ROS-mediated killing, and IL-1 increases AMP synthesis, upregulates TNF receptor (TNFR) expression and restricts the production of type I IFN, which is primarily antagonistic in TB. However, hyperinflammation downstream of excessive cytokine stimulation can promote disease exacerbation (see below), and high doses of TNF cause necroptotic macrophage death and extracellular bacterial replication. Current cytokine-based HDT approaches mostly involve IFNγ or modulators of TNF. For example, the delivery of aerosolized IFNγ to patients with TB has been shown to reduce time to sputum conversion without consistent improvement of the chest radiological outcome105,106. In small trials carried out in cohorts of patients with drug-resistant TB, adjunct therapy with IFNγ, in addition to facilitating bacterial killing, improved lung repair107,108,109. However, cytokine-based HDT strategies that modulate TNF as an adjunct to canonical chemotherapy seem to be more promising, as they considerably shorten therapy duration, improve pathology and limit TB relapse in experimental models (as detailed below).

Whereas type I IFN, including IFNα, qualify for HDT of several viral infections, it seems counter-intuitive for bacterial diseases such as TB given its association with disease progression110,111,112. However, IFNα, when given in adjunct to conventional chemotherapy113,114,115, might provide an interesting treatment option for the resuscitation of dormant Mtb. Only replicating bacilli are susceptible to first- and second-line TB drugs, for example, isoniazid, rifampin and fluoroquinolones, and so the risk–benefit of a 'shock and kill' approach as currently explored for HIV infections should also be considered for difficult-to-treat forms of TB.

Amendment of immune suppression in TB. The expression of inhibitory PD1 molecules is upregulated during persistent antigenic exposure as it occurs in chronic infections, including TB, cancer and sepsis116,117,118. Signalling via PD1 inhibits T cell proliferation and cytokine production and induces lymphocyte apoptosis. Impaired T cell immunity promotes Mtb replication and subsequent tissue damage. Building on the impressive success achieved in cancer immunotherapy119, checkpoint blockade has been considered for TB therapy (Fig. 3). This includes monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that are specific for PD1 (such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and for cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4; such as ipilimumab). The T cell expression of PD1 gradually decreases during canonical chemotherapy, with a concurrent increase in TH1 cell responses120,121,122. Moreover, the expression of PDL1 on macrophages123 and neutrophils124 has been reported in patients with TB and has been linked to impaired T cell and natural killer T (NKT) cell functions122,125. In vitro treatment with a PD1 mAb of cell cultures derived from patients with TB reduced immunosuppression by blocking T cell apoptosis, restoring IFNγ production and triggering IFNγ-dependent killing of Mtb-infected macrophages122,123. Similarly, the increased surface expression of CTLA4 has also been reported in TB121,126,127, and the checkpoint receptor LAG3 was found to be highly expressed by CD4+ T cells and NK cells in the lungs of non-human primates that progressed to active TB, but not in animals with LTBI128. This observation suggests that changes in LAG3 expression patterns influence disease outcome and Mtb replication. Finally, the blockade of TIM3, another checkpoint receptor on T cells, increases the propensity of myeloid cells to kill Mtb. These effects were linked to the increased production of IFNγ by T cells and the increased production of IL-1β by Mtb-infected macrophages129,130. Moreover, release from T cell exhaustion that is caused by the blockade of TIM3 has improved Mtb control in mice that are chronically infected with TB131. However, interventions using checkpoint inhibitors in general warrant caution because blocking the inhibitory effect of PD1 on T cells thereby increases the IFNγ-producing capacity of lung-homing subsets of CD4+ T cells and has caused extensive lung pathology in murine models of TB132. Finally, anti-PD1 therapy can reactivate LTBI133, suggesting that checkpoint blockade should be considered only in adjunct to canonical TB chemotherapy.

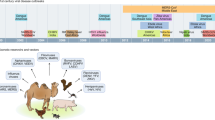

During latent tuberculosis (TB), lung lesions may be absent or may present as solid, eventually fibrotic and mineralized granulomas. During active TB, granulomas progress towards necrosis and caseation, leading to cavitation and bacterial expectoration. Such lesions contain Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) in distinct metabolic and replicative stages: replicating and metabolically active bacilli in caseous granulomas; and non-replicative, dormant bacteria in the hypoxic environment of solid granulomas. In a single patient, different granuloma types coexist that harbour Mtb with an active or a dormant phenotype. Hence, strategies to restrict or to promote inflammation are envisaged as potential host-directed therapy (HDT) for TB. The selection of a particular HDT depends on the rationale for applying it as stand-alone treatment, for example, to limit exacerbated tissue damage, or as an adjunct to canonical TB therapy to promote inflammation and facilitate killing of actively replicating Mtb. Interference with arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism, which generates both pro- and anti-inflammatory metabolites and which also modulates patterns of cell death in infected cells, and interference with cytokine signalling and selected cellular therapies, such as the maturation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and the infusion of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), can correct exacerbated inflammation. The amendment of immune suppression by checkpoint blockade can restrict inflammation by correcting levels of protective interferon-γ (IFNγ); however, this may facilitate hyper-inflammation once pathological levels of the cytokine are achieved. Drugs interfering with such mechanisms limit immunopathology and help to preserve tissue functionality. Immune-suppressive drugs, notably glucocorticoids and biologics, besides limiting life-threatening inflammation, reduce the local abundance of host-protective cytokines and thereby facilitate lesion caseation and promote the resuscitation of dormant Mtb. Metabolically active bacteria can be targeted by canonical TB chemotherapy. Limiting vasculogenesis restricts nutrient supply and access of Mtb-permissive cells to granulomas. Metformin, glycolytic agents and kinase inhibitors interfere with metabolic pathways activated under hypoxic conditions that support bacillary replication, and inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) limits collateral damage and Mtb spread. Boxes indicate drugs that interfere with angiogenesis, metabolic pathways and factors that promote tissue damage. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4- carboxamide ribonucleotide; AMPK, 5′ adenosine monophosphate- activated protein kinase; COX, cyclooxygenase; CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein 4; GAL9, galectin 9; LOX, lipoxygenase; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NK, natural killer; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; PDL1, PD1 ligand 1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; TCR, T cell receptor; TIM3, T cell immunoglobulin mucin receptor 3; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Release from immune suppression can also be achieved through cellular therapy with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Although MSCs may be used as a niche for dormant Mtb134,135,136, the propensity of MSCs to induce regulatory phenotypes in DCs and T cells, and to promote tissue repair, render them attractive tools for HDT. The safety of this approach has been demonstrated in a phase I trial, in which 30 patients with multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR TB) received an infusion of a single dose of autologous MSCs137. Higher cure rates and radiological improvement were observed in a small cohort study comprising 36 patients with MDR TB138. The delivery of MSCs is ready to enter a phase II clinical trial as adjunct therapy for drug-resistant TB139.

Cytokine therapy in the immunosuppressive phase of sepsis. Although early deaths in sepsis are often due to cytokine-mediated hyper-inflammation, numerous studies have provided compelling evidence that, if sepsis is protracted (lasting longer than 3 days), it evolves into a highly immunosuppressive state140,141 during which the majority of septic deaths occur and for which new immuno-adjuvant therapy is needed to restore host immunity and to improve survival140,141. Currently, this is one of the most active areas of sepsis research142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149 (Fig. 4; Supplementary information S3 (table)).

During protracted sepsis, several mechanisms and pathways that impair the host's ability to defend against sepsis become activated with limited collateral damage and lower survival rates. Drugs that activate host immunity or that block inhibitory pathways offer new therapeutic approaches in sepsis. The four boxes on the top and left indicate potential immuno-adjuvant therapies that enhance host immunity. The three boxes on the right with inhibitory arrows indicate drugs that prevent inhibitory pathways from impairing host immunity. Bacteria are indicated by the orange rod-shaped structures that are shown engulfed inside the macrophage and at the bottom of the figure. CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte protein 4; FLT3L, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HDT, host-directed therapy; IFNγ, interferon-γ; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; MØ, macrophage; PD1, programmed cell death 1; PDL1, PD1 ligand 1; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TH2, T helper 2; Treg, T regulatory cell.

Two immune-enhancing cytokines that have already undergone small therapeutic trials in sepsis are granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IFNγ142,143,144,145,146,147. GM-CSF stimulates the generation of granulocytes and monocytes or macrophages; a predominant function of IFNγ is to activate monocytes and macrophages. Although small early studies of GM-CSF and IFNγ in patients with protracted sepsis seemed promising142,143, subsequent trials failed to demonstrate a consistent benefit144,149. More recently, investigators have targeted therapy with GM-CSF and IFNγ to patients who are in the immunosuppressive phase of sepsis146,147,148. In a study of 38 patients with sepsis with low monocyte HLA-DR expression, GM-CSF therapy shortened the duration of mechanical ventilation, improved the severity of illness scores, and reduced the length of intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stays147. GM-CSF was also efficacious in a study of immunosuppressed paediatric patients with sepsis, who were identified by measuring ex vivo whole-blood lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated TNF production148. GM-CSF administration to patients improved ex vivo LPS-stimulated whole-blood TNF production and decreased the risk of hospital-acquired infections. Based on these encouraging results, a multicentre trial of GM-CSF in sepsis is currently under way150.

IFNγ is also receiving renewed interest for HDT for patients in the immunosuppressive phase of sepsis. A multicentre trial of 416 trauma patients, many of whom developed sepsis, revealed that patients treated with IFNγ had fewer infection-related deaths, and there were also fewer overall deaths reported in this group149. In a study of nine patients with sepsis with decreased monocyte HLA-DR expression and reduced ex vivo LPS-stimulated whole-blood TNF who were treated with IFNγ, eight patients benefited from restored monocyte function and survived the septic insult142. IFNγ was also tested in eight patients with invasive fungal infections, and markedly improved monocyte HLA-DR expression and an enhanced ability of leukocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines were observed146. A trial of IFNγ in immunosuppressed patients with bacterial sepsis is ongoing151.

Perhaps the most exciting immuno-adjuvant agent in sepsis is IL-7, a cytokine that is essential for the survival of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. IL-7 has multiple beneficial effects on host immunity, including the proliferation and activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and it also increases the surface expression of cell adhesion molecules, thereby facilitating the trafficking of T cells to sites of infection. IL-7 also counteracts sepsis-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes. This anti-apoptotic effect of IL-7 is particularly important because the severe depletion of immune effector cells — including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells and DCs — is a pathophysiological hallmark of sepsis141,152,153,154. Multiple studies from independent laboratories have shown that IL-7 improves survival in various clinically relevant animal models of sepsis155. Importantly, it has been shown that IL-7 is effective in reversing T cell dysfunction in circulating immune cells from patients with septic shock154. So far, IL-7, which has been given to more than 300 patients in the treatment of various disorders, has consistently increased circulating absolute lymphocyte counts, and has been well tolerated152. In patients with AIDS, IL-7 restored the gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue, leading to decreased circulating markers of inflammation153. This effect may also be particularly helpful in patients with sepsis, as the loss of gut barrier integrity in sepsis is thought to facilitate the translocation of bacteria and/or LPS into the circulation, thereby driving the inflammatory response. IL-7 has also been administered on a compassionate basis to patients with lymphopenia and John Cunningham (JC) virus-induced progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy. In this setting, IL-7 increased lymphocyte counts and decreased JC virus load and survival156. A multicentre clinical trial of IL-7 in sepsis is currently ongoing157.

Checkpoint blockade to boost host immunity in sepsis. Another highly promising therapy in sepsis is the blockade of PD1 and PDL1 (Fig. 4; Supplementary information S3 (table)). A post-mortem study in patients with sepsis showed findings that were consistent with T cell exhaustion, including the upregulation of PD1 and PDL1 on immune cells and severely impaired cytokine secretion116. Importantly, multiple independent groups have reported that PD1 is overexpressed on circulating T cells in patients with sepsis and that the incubation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with specific antibodies against PD1 or PDL1 can restore impaired cytokine production and can decrease sepsis-induced apoptosis116,117,118. Moreover, animal models of sepsis have shown that the delayed administration of PD1- and PDL1-blocking antibodies improves survival. Given the surprising overlap in the immunological deficits in cancer and sepsis158, and the remarkable success of PD1 and PDL1 inhibition in cancer immunotherapy119, there is a strong rationale for trials of these antibodies in sepsis, and a small multicentre, dose safety trial of anti-PDL1 in patients with sepsis has recently been completed159.

Other immunomodulatory agents to boost host immunity in sepsis. Another encouraging approach to boosting immunity in patients with sepsis is treatment with thymosin α1, a 28-amino acid polypeptide that was originally derived from mouse thymic extracts (Supplementary information S3 (table)). Although the exact mechanism of action of thymosin α1 is unknown, it is currently thought that it functions, in part, as a TLR agonist. Thymosin α1 is known to enhance T cell and DC function, to increase IL-12 production, and to improve antibody responses160. Similar to treatment with PD1 and PDL1 inhibitors, thymosin α1 has shown benefit in the treatment of both cancer and infectious diseases. Thymosin α1 showed efficacy in improving survival in a multicentre, randomized, controlled trial of 361 patients with sepsis. Compared with patients treated with placebo, patients who were treated with thymosin α1 had increased monocyte HLA-antigen D related (DR) expression and a decrease in 28-day mortality160. Based on these results, a larger multicentre trial of thymosin α1 in sepsis has been initiated161.

Reducing exacerbated inflammation

A major challenge for selective antiviral and antibacterial therapies is the timing of administration. For example, in most acute viral infections, disease symptoms manifest when viraemia is already declining and so selective antiviral therapy is often initiated too late. However, suppressing exacerbated disease symptoms that are triggered by the pathogen at later time points can reduce morbidity and mortality. Such HDTs require a detailed understanding of pathogen–host interactions, but hold promise for reducing disease symptoms to the level of a self-limiting infection.

Cytokine storms in viral infections

The devastating consequences of viral infections frequently arise from an excessive, often uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Such cytokine storms can be triggered by multiple mechanisms, including the hyperactivation of TLRs. Examples include dengue haemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome, which are most often caused by secondary infection with a heterologous serotype of dengue virus (DENV). These serious cases are characterized by the uncontrolled hyperproduction of cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF, IFNs, CC motif chemokine 8 (CCL8) and CXC motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), ultimately leading to vascular leakage and shock syndrome162. Key drivers of cytokine storms seem to be high-level viraemia, the ligation of DENV–immunoglobulin complexes to myeloid or mast cells, and the secreted version of the viral protein NS1, all of which drive excessive pro-inflammatory responses, while reducing anti-inflammatory ones. NS1 binds to TLR4 and induces the production of the same cytokines that are detected during the course of severe dengue disease and enhances vascular permeability163. Blocking NS1-mediated TLR4 activation with a TLR4 antagonist or with a TLR4-specific antibody markedly reduced vascular leakage both in vitro and in a mouse model of DENV infection163. Moreover, autophagy induction in endothelial cells seems to be required for NS1-induced vascular leakage, which can be blocked by autophagy inhibitors164. Finally, DENV NS1 also promotes vascular leakage by inducing the expression of enzymes such as sialidases and heparanase that degrade the glycocalyx layer that lines the endothelium on the luminal side, thus diminishing its barrier function and enhancing fluid extravasation165. Although to the best of our knowledge no clinical trials have yet been conducted, these results hold great promise for the suppression of exacerbated inflammation by targeting NS1-specific ligands and receptors. Alternative strategies for HDT-based symptomatic treatment of severe dengue disease are based on immunosuppressive therapy with steroids such as prednisolone, but so far these have met with only limited success166,167.

The concept of modulating inflammation was also evaluated in influenza virus infection, in which cytokine storms can cause acute and sometimes fatal immune-mediated pulmonary injury. It has been proposed that acute lung injury that is triggered by infection with respiratory viruses and bacteria induces, via ROS, the production of pathogenic oxidized lipids that activate TLR4 and induce a cytokine storm168. Consistently, Tlr4-deficient mouse mutants are protected from lethal challenge with a mouse-adapted influenza virus strain169. Notably, the TLR4 antagonist eritoran, an investigational drug for the treatment of severe sepsis, consistently decreased lung pathology and clinical symptoms in various in vivo influenza models170. These encouraging results, together with the well-established safety profile of eritoran and the observation that it can be given up to 6 days after influenza virus infection in mice, qualifies this compound as an interesting candidate for the prevention of severe influenza.

Several alternative strategies to suppress an influenza virus-induced cytokine storm are currently being pursued. One approach is based on agonists of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor such as AAL-R. This compound reduced mortality in influenza-infected mice by ~80%, and reduced mortality by 96% when given in combination with the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir171. The anti-inflammatory effect of AAL-R is mediated, at least in part, by limiting the IFNα auto-amplification loop in plasmacytoid DCs, which are the main producers of this cytokine.

Cyclooxygenases (COX) that catalyse the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and that modulate immune responses and inflammation are other HDT targets in severe influenza. Beneficial effects have been reported with inhibitors that target COX2, such as the combination of the two COX2 inhibitors celecoxib and mesalazine with the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir. In a study with this triple regimen, the survival rate of mice infected with a highly lethal influenza virus strain was significantly improved (P = 0.02), as were the survival time (P <0.02) and inflammation markers (P <0.01), relative to animals receiving only the neuraminidase inhibitor172. However, systematic evaluations of such treatment modalities in patients infected with influenza virus are still lacking.

Statins for HDTs have been assessed in clinical trials in patients infected with influenza virus because of their anti-inflammatory properties, but the results have been conflicting173,174,175,176,177. Other approaches to anti-inflammatory treatment are based on agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), which is considered to be the most promising target among all three PPAR subtypes. Several studies in mouse models have shown that PPARγ agonists decrease inflammation and influenza morbidity178,179,180. Whether this approach is effective in humans remains to be determined.

Increasing evidence suggests that neutrophils have a major role in severe lung pathology on influenza virus infection. Although these cells contribute to protection against influenza virus infection, heightened neutrophil recruitment correlates with the virulence of a given influenza virus strain181. For this reason, inhibitors of neutrophil chemotaxis have been developed. Danirixin is a clinically advanced inhibitor of CXCR2, a chemokine receptor that drives neutrophil migration. Danirixin was developed for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and it has been found to be well tolerated and it does not induce major safety concerns182. Based on these results, a phase II clinical trial is currently recruiting patients to receive Danirixin either alone or in combination with the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir for the therapy of influenza virus infection in adults183.

Modulating inflammation in TB and sepsis

TB pathophysiology is characterized by non-resolving inflammation as a consequence of host failure to eliminate Mtb. Inflammatory pathways, involving both pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (primarily cytokines and lipids) are sequentially turned on and off in TB184. Accordingly, mechanisms that restrict and promote inflammation are relevant both at distinct disease stages and at specific infection sites. An imbalance of these responses, rather than solely an exacerbated pro-inflammatory response, is the characteristic feature of TB. Different forms of lesions, such as solid, fibrotic, mineralized and caseating granulomas, as well as cavities and foci of pneumonia, can coexist within a patient185; even within a single lesion, inflammatory mediators are segregated into distinct regions186. Therefore, concurrent application of pro- and anti-inflammatory intervention may become a necessity. Such a therapy concept for the spatiotemporal coexistence of hyper- and hypo-inflammation poses a great challenge that has barely begun to be addressed experimentally187. Current HDT approaches comprise small molecules and biologics that target anti- and pro-inflammatory pathways as adjunctive measures for TB therapy (Fig. 3; Supplementary information S2 (table)).

Targeting eicosanoids in TB. Metabolites of arachidonic acid modulate inflammation, cell death and immunity, and they have been investigated as HDTs against TB188. The COX product prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a pro-apoptotic eicosanoid that protects against necrotic cell death during mycobacterial infections188. Mtb skews the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway towards lipoxygenase (LOX) activation and the generation of pro-necrotic lipoxin A4 (LXA4) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4). The modulation of this axis by zileuton, a clinically licensed 5-LOX inhibitor for the treatment of asthma, and the nasal application of PGE2, can restrict lung pathology in murine TB189 (Fig. 3). Combination therapy of zileuton and PGE2 boosts cytoprotective IL-1β production by limiting type I IFN production and by restricting Mtb replication. Balanced PGE2 and LXA4 levels are probably involved in the successful control of Mtb in LTBI compared with active TB. During active TB, IL-1 concentrations are increased190,191,192 and the abundance of IL-1 correlates with the extent of tissue damage that is mediated by neutrophils193. In LTBI, the early production of PGE2 seems to be essential for protection, whereas heightened PGE2 levels at later stages of infection impair immune defence and promote progression to disease194,195. COX inhibitors — such as ibuprofen195, aspirin196 and diclofenac197,198 — given alone or in combination with canonical TB drugs, limit bacillary loads and prolong the survival of TB-susceptible mice. In addition, ibuprofen has direct antitubercular activity199 (Fig. 3). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, inhibit PGE2 production and enhance LXA4 generation, which in addition to its effects on Mtb-induced cell death also shows anti-inflammatory functions. NSAIDs, by limiting PGE release and inducing lipoxin production, lower TNF abundance188, and thus are likely to ameliorate local inflammation. Certain NSAIDs, notably aspirin, have already entered clinical trials for TB200,201,202. Ibuprofen was also registered in a phase II clinical trial for therapy of XDR TB203.

Modulation of inflammation in TB. Interfering with cytokine signalling is another promising HDT that warrants consideration (Fig. 3). Several strategies, congruent with the diversity of cytokines involved in controlling TB inflammation, have been envisaged139. The blockade of cytokine signalling to reduce the local influx of inflammatory cells can be achieved by targeting IL-6 and TNF.

TNF is a crucial cytokine in immune defence against TB, and although it is required for granuloma integrity during LTBI, high levels of TNF can exacerbate pathology204. These observations have paved the way for several HDT approaches, by which TNF levels are decreased to restrict exacerbated pathology, or alternatively to achieve better drug penetration into lesions by destabilizing solid and eventually fibrotic granulomas, and to facilitate the killing of Mtb by resuscitating dormant bacteria to replicative activity.

Given the link between cell death and the propagation of inflammatory responses during Mtb infection205, restricting TNF-induced necroptotic cell death of infected macrophages through the delivery of alisporivir and desipramine could limit the local recruitment of Mtb-permissive cells205. Alisporivir and desipramine restrict ROS-mediated necrosis by blocking cyclophilin D and acid sphingomyelin, respectively. TNF blockers are widely used in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease and thus can be readily repurposed for HDT in TB. In several cases, mAbs against TNF (such as infliximab and adalimumab) have shown beneficial effects against life-threatening TB206,207. Etanercept, a soluble TNF receptor, has demonstrated modest benefits in adjunct therapy in TB208. However, in contrast to etanercept, mAbs against TNF can reactivate LTBI by destabilizing granulomas204. Whereas this is a contraindication for rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic inflammatory diseases, it could be beneficial as adjunct therapy for TB to facilitate the killing of metabolically active bacilli and may represent a 'shock and kill' strategy209.

IL-6 concentrations correlate with the severity of lung damage in patients with TB210,211, reverting to normal concentrations upon chemotherapy212. mAbs that inhibit IL-6 or IL-6R (such as siltuximab and tocilizumab) are in clinical use for rheumatic diseases, and the application of such biologics has not been associated with TB reactivation in preclinical models of TB. Therefore, on the one hand, these mAbs do not pose a risk of reactivation to individuals with LTBI; on the other hand, they are not suited for 'shock and kill' interventions213.

Various classes of drugs that affect TNF signalling and that reactivate LTBI have shown potential for HDT in TB. For example, the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, which is licensed for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, has been associated with the reactivation of LTBI214 and impaired bacillary containment in murine TB215. The coadministration of tofacitinib with canonical chemotherapy was beneficial in selected models of TB, suggesting that the activity of JAK inhibitors is influenced by patterns of inflammation and granulomatous responses216. Additional approaches to modulate TNF signalling or abundance include thalidomide analogues48 and phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors217. Thalidomide improved treatment outcome in a pilot study in pulmonary TB218; however, a clinical trial to test adjunct thalidomide therapy in paediatric TB was terminated owing to adverse events, including skin rash, hepatitis, severe neutropenia and thrombocytopenia219. As thalidomide is teratogenic, thalidomide analogues with better safety profiles have been synthesized. Analogues that inhibit PDE4 signalling by increasing cAMP levels have shown beneficial effects as adjuncts to canonical TB chemotherapy in mouse and rabbit models of infection220,221,222. These compounds accelerate bacillary clearance and promote lung repair. Other PDE inhibitors, including cilostazol (an inhibitor of PDE3) and sildenafil (an inhibitor of PDE5), showed similar effects215,223. The nonspecific PDE inhibitor pentoxifylline was unsuccessful in TB trials, despite reducing TNF levels and inducing TB progression when administered as a monotherapy in mouse models224,225. The most advanced PDE inhibitor in preclinical studies, CC-11050, has completed phase I trials48, and a phase II trial is planned to compare CC-11050, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus, the thioredoxin reductase inhibitor auranofin and vitamin D as HDT adjuncts to standard chemotherapy for the accelerated cure of drug-sensitive TB95,202,208.

Another approach to restricting local inflammation includes the co-delivery of glucocorticoid receptor agonists, such as prednisolone and dexamethasone, with TB chemotherapy. The effects of glucocorticoids on immune cells are multifaceted. Corticosteroids reduce the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, notably TNF, restrict the migration of inflammatory cells and cause apoptosis. For patients with TB, such interventions are beneficial because they counteract inflammation and are likely to improve drug penetration into granulomas, fostering the clearance of metabolically active Mtb as a consequence of lesion destabilization. Adjunct treatment with glucocorticoids began more than five decades ago for patients with different forms of the disease, including TB meningitis, TB pericarditis and pulmonary TB226. In many cases, corticosteroids seemed to improve the resolution of lesions, albeit without major long-term benefits227. A recent meta-analysis indicated that glucocorticoid receptor agonists mostly reduce TB mortality when the central nervous system is affected, notably, in TB meningitis227. The benefits of glucocorticoids depend on the genotype of the patient228, indicating that divergent effects are the result of different patterns of inflammation — genotype-specific hypo- or hyper-inflammation — in different patients, which influence Mtb replication. A meta-regression analysis of pulmonary TB revealed that, in addition to genotype effects, the dosage of corticosteroids affects sputum conversion in patients with TB229. A phase II clinical trial that tested corticosteroids in combination with standard chemotherapy for TB in patients co-infected with HIV indicated faster sputum conversion, but also adverse events at high dosages230. Further studies to more carefully assess the risks and benefits of glucocorticoids are underway, and the delivery of glucocorticoids has been prioritized as an HDT for specific patient groups, such as those suffering from TB and AIDS comorbidity. The use of prednisone or the NSAID drug meloxicam for the prevention of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which is observed in patients co-infected with HIV and Mtb, has reached phase III and phase II trial stages, respectively231,232. Similarly, the glucocorticoid receptor agonist dexamethasone is now in phase II/III and phase IV trials for the therapy of meningeal TB233,234.

Anti-cytokine treatment in early hyper-inflammatory sepsis. Sepsis has traditionally been considered a disorder that is caused by an uncontrolled, exacerbated host inflammatory response to invading pathogens. This concept was logical given that patients with sepsis frequently present with signs of overwhelming inflammation, as typified by high-spiking fever, shock and acute respiratory distress. The discovery of TNF and other cytokines reinforced the concept that morbidity and mortality in sepsis were due to an unbridled cytokine-mediated host response. The fact that inhibitors of TNF prevented death in animal models of sepsis caused by endotoxin and Escherichia coli further supported the idea that morbidity in sepsis is due to excessive cytokine-mediated inflammation.

Some patients with sepsis quickly succumb to an overwhelming cytokine-mediated hyper-inflammatory response. Typical examples of these types of disease include meningococcaemia, rapidly invasive necrotizing soft tissue infections with group A β-haemolytic streptococci, necrotizing pneumonia caused by Panton–Valentine leukocidin-secreting Staphylococcus aureus, and overwhelming Clostridia difficile colitis. Patients with these types of toxin-mediated catastrophic infections may benefit from anti-cytokine-based therapy that blocks the mediators of the highly lethal acute inflammatory response. However, this is a small subset of patients with sepsis and any therapy that is used to block the host response to pathogens should be short acting, applied early in sepsis and only used in patients with sepsis who manifest evidence of uncontrolled inflammation.

Although previous trials of drugs that inhibit the activity of TNF or IL-1 failed to show any benefit in the general population of patients with sepsis, there were indications that particular subsets of patients with sepsis may have had a beneficial response235,236,237. In this regard, a recent reanalysis of de-identified data from a phase II trial of the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in severe sepsis revealed a highly significant improvement in 28-day survival in a subset of patients who had concurrent hepatobiliary dysfunction and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)237. Because of the concomitant liver injury and DIC, investigators speculated that this small subset of patients may have had sepsis-induced macrophage activation syndrome, which is characterized by uncontrolled macrophage and T cell activation, haemophagocytosis and marked increases in circulating cytokines.

HDTs targeting inflammation in both viral infections and sepsis share similarities, and eritoran and S1P agonists are well advanced in the clinical trial pipeline either aimed at the hyper-inflammatory phase or aimed at systemic effects, respectively. Only a few anti-inflammatory strategies (such as COX2 inhibitors) are intended for both TB and viral diseases, and the systemic delivery of glucocorticoids for immunosuppression is in clinical trials for TB only.

Host reactions at the site of infection

Pathogens induce variable tissue changes according to their site of entry and residence, their specific pathophysiology and their propensity to spread systemically. Agents that cause extensive remodelling of the affected tissue, such as Mtb, use the resulting lesions to replicate and to hide from host defences. By contrast, microorganisms that spread systemically and cause sepsis develop strategies to skew immunity in a stage-specific and global manner. Modulating host immunity in a localized or generalized manner is an attractive HDT option for TB.

Targeting granulomas in TB

Strategies directed towards limiting granuloma expansion and instability rather than neoformation aim to augment drug penetration into lesions, balance inflammatory responses and modify the metabolic features of immune cells to facilitate tissue repair (Fig. 3; Supplementary information S2 (table)). The spectrum of granulomas of different stages in patients with TB demands the careful consideration of the spatiotemporal context for each different approach (highlighted below).

Targeting vascular biology in TB granuloma. Granulomas have a reduced blood supply, particularly at sites of necrosis, thereby restricting the access of chemotherapeutics to the site of Mtb infection. Consequently, HDTs that promote vascular perfusion can improve drug delivery. However, such a strategy may equally benefit Mtb by facilitating access to nutrients and permissive host cells. The situation is somewhat reminiscent of neoplastic diseases, in which tumours actively promote angiogenesis to improve blood supply and to alleviate local hypoxia at late stages of tumour development. The outcome of vasculogenesis-focused HDT for TB is likely to depend on the stage of disease and the treatment objective, namely, interference with either angiogenesis or vascular permeability. In patients with active TB, factors that induce neovascularization, notably vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR, are abundant in the circulation238,239,240 and have been proposed as biomarkers of disease severity241. Bevacizumab, a mAb against VEGF, is approved for the treatment of certain cancers, and several other antibodies that target VEGF or VEGFR are in clinical trials. In animal models of TB, VEGF and VEGFR inhibitors have revealed beneficial effects when given in combination with conventional drugs, by limiting bacterial dissemination and boosting the activity of drugs that target hypoxic Mtb242,243. Conversely, there is a risk that the administration of such biologics without concurrent chemotherapy may promote TB reactivation244,245 and bacillary dissemination240.

In addition to neovascularization, vascular dysfunction emerges as another commonality between cancer and TB. Mtb stimulates the angiopoietin 2 (ANG2)–TIE2 axis to increase blood vessel permeability. Vascular endothelial protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors, such as molecules that are closely related to AKB-9778 (Aerpio Therapeutics), which dephosphorylate TIE2 and blunt signalling in endothelia, have been shown to restrict Mtb replication in a zebrafish model of TB246. These results indicate that HDT strategies that modulate vascular biology by stabilizing the permeability of the vasculature independently of infection-induced neovascularization limit bacterial growth or dissemination.