Abstract

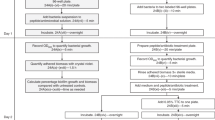

A major reason for bacterial persistence during chronic infections is the survival of bacteria within biofilm structures, which protect cells from environmental stresses, host immune responses and antimicrobial therapy. Thus, there is concern that laboratory methods developed to measure the antibiotic susceptibility of planktonic bacteria may not be relevant to chronic biofilm infections, and it has been suggested that alternative methods should test antibiotic susceptibility within a biofilm. In this paper, we describe a fast and reliable protocol for using 96-well microtiter plates for the formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms; the method is easily adaptable for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. This method is based on bacterial viability staining in combination with automated confocal laser scanning microscopy. The procedure simplifies qualitative and quantitative evaluation of biofilms and has proven to be effective for standardized determination of antibiotic efficiency on P. aeruginosa biofilms. The protocol can be performed within ∼60 h.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Costerton, J.W., Stewart, P.S. & Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284, 1318–1322 (1999).

Ramsey, B.W. Management of pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 179–188 (1996).

Parsek, M.R. & Singh, P.K. Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 677–701 (2003).

Mah, T.F. et al. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426, 306–310 (2003).

Moskowitz, S.M., Foster, J.M., Emerson, J. & Burns, J.L. Clinically feasible biofilm susceptibility assay for isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 1915–1922 (2004).

Nickel, J.C., Ruseska, I., Wright, J.B. & Costerton, J.W. Tobramycin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells growing as a biofilm on urinary catheter material. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27, 619–624 (1985).

Hoyle, B.D. & Costerton, J.W. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: the role of biofilms. Prog. Drug Res. 37, 91–105 (1991).

Gilbert, P. & McBain, A.J. Biofilms: their impact on health and their recalcitrance toward biocides. Am. J. Infect. Control 29, 252–255 (2001).

Gilbert, P., Maira-Litran, T., McBain, A.J., Rickard, A.H. & Whyte, F.W. The physiology and collective recalcitrance of microbial biofilm communities. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 46, 202–256 (2002).

Smith, A.L., Fiel, S.B., Mayer-Hamblett, N., Ramsey, B. & Burns, J.L. Susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates and clinical response to parenteral antibiotic administration: lack of association in cystic fibrosis. Chest 123, 1495–1502 (2003).

Hall-Stoodley, L. & Stoodley, P. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell Microbiol. 11: 1034–43 (2009).

Worlitzsch, D. et al. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 317–325 (2002).

Moskowitz, S.M., Foster, J.M., Emerson, J.C., Gibson, R.L. & Burns, J.L. Use of Pseudomonas biofilm susceptibilities to assign simulated antibiotic regimens for cystic fibrosis airway infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56, 879–886 (2005).

Keays, T. et al. A retrospective analysis of biofilm antibiotic susceptibility testing: a better predictor of clinical response in cystic fibrosis exacerbations. J. Cyst. Fibros. 8, 122–127 (2009).

Foweraker, J. Recent advances in the microbiology of respiratory tract infection in cystic fibrosis. Br. Med. Bull. 89, 93–110 (2009).

Ceri, H. et al. The Calgary Biofilm Device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 1771–1776 (1999).

Sandoe, J.A., Wysome, J., West, A.P., Heritage, J. & Wilcox, M.H. Measurement of ampicillin, vancomycin, linezolid and gentamicin activity against enterococcal biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57, 767–770 (2006).

Brooun, A., Liu, S. & Lewis, K. A dose-response study of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 640–646 (2000).

De Kievit, T.R. et al. Multidrug efflux pumps: expression patterns and contribution to antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1761–1770 (2001).

Olson, M.E., Ceri, H., Morck, D.W., Buret, A.G. & Read, R.R. Biofilm bacteria: formation and comparative susceptibility to antibiotics. Can. J. Vet. Res. 66, 86–92 (2002).

Tre-Hardy, M., Vanderbist, F., Traore, H. & Devleeschouwer, M.J. In vitro activity of antibiotic combinations against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm and planktonic cultures. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31, 329–336 (2008).

Pierce, C.G. et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1494–1500 (2008).

Repp, K.K., Menor, S.A. & Pettit, R.K. Microplate Alamar blue assay for susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Med. Mycol. 45, 603–607 (2007).

Ramage, G., Vande, W.K., Wickes, B.L. & Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Standardized method for in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2475–2479 (2001).

Huang, C.T., Yu, F.P., McFeters, G.A. & Stewart, P.S. Nonuniform spatial patterns of respiratory activity within biofilms during disinfection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2252–2256 (1995).

McFeters, G.A., Pyle, B.H., Lisle, J.T. & Broadaway, S.C. Rapid direct methods for enumeration of specific, active bacteria in water and biofilms. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 85, 193S–200S (1999).

Pitts, B., Hamilton, M.A., Zelver, N. & Stewart, P.S. A microtiter-plate screening method for biofilm disinfection and removal. J. Microbiol. Methods 54, 269–276 (2003).

Peeters, E., Nelis, H.J. & Coenye, T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J. Microbiol. Methods 72, 157–165 (2008).

O'Toole, G.A. & Kolter, R. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 295–304 (1998).

Biggerstaff, J.P. et al. New methodology for viability testing in environmental samples. Mol. Cell Probes 20, 141–146 (2006).

Falcioni, T., Papa, S. & Gasol, J.M. Evaluating the flow-cytometric nucleic acid double-staining protocol in realistic situations of planktonic bacterial death. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1767–1779 (2008).

Stocks, S.M. Mechanism and use of the commercially available viability stain, BacLight. Cytometry A 61, 189–195 (2004).

Boulos, L., Prevost, M., Barbeau, B., Coallier, J. & Desjardins, R. LIVE/DEAD BacLight: application of a new rapid staining method for direct enumeration of viable and total bacteria in drinking water. J. Microbiol. Methods 37, 77–86 (1999).

Hoerr, V., Ziebuhr, W., Kozitskaya, S., Katzowitsch, E. & Holzgrabe, U. Laser-induced fluorescence-capillary electrophoresis and fluorescence microplate reader measurement: two methods to quantify the effect of antibiotics. Anal. Chem. 79, 7510–7518 (2007).

Gillis, R.J. & Iglewski, B.H. Azithromycin retards Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 5842–5845 (2004).

Haagensen, J.A. et al. Differentiation and distribution of colistin- and sodium dodecyl sulfate-tolerant cells in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 189, 28–37 (2007).

Hentzer, M. et al. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 22, 3803–3815 (2003).

Kaneko, Y., Thoendel, M., Olakanmi, O., Britigan, B.E. & Singh, P.K. The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 877–888 (2007).

Stewart, P.S. & Franklin, M.J. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 199–210 (2008).

Teitzel, G.M. & Parsek, M.R. Heavy metal resistance of biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 2313–2320 (2003).

Pamp, S.J., Sternberg, C. & Tolker-Nielsen, T. Insight into the microbial multicellular lifestyle via flow-cell technology and confocal microscopy. Cytometry A 75, 90–103 (2009).

Kirov, S.M. et al. Biofilm differentiation and dispersal in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microbiology 153, 3264–3274 (2007).

Harrison, J.J. et al. The use of microscopy and three-dimensional visualization to evaluate the structure of microbial biofilms cultivated in the Calgary Biofilm Device. Biol. Proced. Online 8, 194–215 (2006).

Müsken, M., DiFiore, S., Dötsch, A., Fischer, R. & Häussler, S. Genetic determinants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm establishment. Microbiology 156, 431–441 (2010).

Liberati, N.T. et al. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2833–2838 (2006).

Mueller, L.N., de Brouwer, J.F., Almeida, J.S., Stal, L.J. & Xavier, J.B. Analysis of a marine phototrophic biofilm by confocal laser scanning microscopy using the new image quantification software PHLIP. BMC. Ecol. 6, 1 (2006).

Merod, R.T., Warren, J.E., McCaslin, H. & Wuertz, S. Toward automated analysis of biofilm architecture: bias caused by extraneous confocal laser scanning microscopy images. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4922–4930 (2007).

Hoffman, L.R. et al. Aminoglycoside antibiotics induce bacterial biofilm formation. Nature 436, 1171–1175 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Suerbaum for providing the clinical P. aeruginosa strains, M. Pletz for sputum samples and L. Szekely and his group for help and assistance in the microscopic facility at the Karolinska Institute. M.M. was supported by the International Research Training Group 1273 funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Financial support from Mukoviszidose e.V. and from Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., S.D.F., U.R. and S.H. designed the study. M.M. and S.D.F. performed the experiments, M.M. and S.H. analyzed the data, S.D.F. gave technical support, and M.M. and S.H. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1s

Visualization of the image processing procedure. (a) Original, plus (b) Background-subtracted, (c) Otsu-thresholded and (d) Outliers-removed images of (1) Syto9 fluorescence and (2) PI fluorescence as well as a (3) Colored overlay of both fluorescent images from a biofilm stack of the clinical isolate 5520 treated with 32 µg ml-1 ceftazidime (Syto9=blue, PI=yellow, overlap=white). (PDF 511 kb)

Supplementary Figure 2s

Comparison of two antibiotic treated PA14 biofilms. Individual pseudocolor merged slices of processed image stacks from PA14 biofilms treated with (a) 2 µg ml-1 and (b) 512 µg ml-1 tobramycin, starting from plane 0 (plastic surface) to plane 14 with a spacing distance of 3 µm (Syto9=blue, PI=yellow, overlap=white). (PDF 738 kb)

Supplementary Figure 3s

Responsiveness of the meropenem-treated biofilms. Distribution of the PI stained (dark), the co-localized (hatched) and the Syto9 stained (light) biovolume and CFU counts (solid white line) of PA14 and 5 clinical strains exposed to increasing concentrations of meropenem. The black dotted line marks the 80 % threshold of PI (and co-localized) fluorescence. Biovolume data are mean values of three independent replicates. The overall SD for the green, the co-localized and the red fraction are: PA14 (4.5 % / 4.9 % / 3.9 %), 5497 (6.6 % / 3.0 % / 6.7 %), 5520 (4.4 % / 3.4 % / 5.3 %), 5522 (4.0 % / 4.0 % / 3.5 %), 5524 (4.0 % / 3.7 % / 4.6 %) and 5529 (4.8 % / 2.7 % / 4.4 %). (PDF 320 kb)

Supplementary Figure 4s

Responsiveness of the ceftazidime-treated biofilms. Distribution of the PI stained (dark), the co-localized (hatched) and the Syto9 stained (light) biovolume and CFU counts (solid white line) of PA14 and 5 clinical strains exposed to increasing concentrations of ceftazidime. The black dotted line marks the 80 % threshold of PI (and co-localized) fluorescence. Biovolume data are mean values of three independent replicates. The overall SD for the green, the co-localized and the red fraction are: PA14 (3.5 % / 4.0 % / 2.2 %), 5497 (6.2 % / 3.4 % / 7.4 %), 5520 (5.5 % / 3.0 % / 7.0 %), 5522 (2.7 % / 3.4 % / 2.3 %), 5524 (6.5 % / 3.0 % / 5.3 %) and 5529 (6.1 % / 3.1 % / 5.9 %). (PDF 322 kb)

Supplementary Figure 5s

Responsiveness of the ciprofloxacin-treated biofilms. Distribution of the PI stained (dark), the co-localized (hatched) and the Syto9 stained (light) biovolume and CFU counts (solid white line) of PA14 and 5 clinical strains exposed to increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin. The black dotted line marks the 80 % threshold of PI (and co-localized) fluorescence. Biovolume data are mean values of three independent replicates. The overall SD for the green, the co-localized and the red fraction are: PA14 (4.3 % / 3.5 % / 2.5 %), 5497 (2.4 % / 4.7 % / 5.6 %), 5520 (6.3 % / 3.4 % / 7.2 %), 5522 (4.6 % / 3.9 % / 4.0 %), 5524 (7.1 % / 4.0 % / 5.0 %) and 5529 (4.9 % / 3.2 % / 6.9 %). (PDF 315 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Müsken, M., Di Fiore, S., Römling, U. et al. A 96-well-plate–based optical method for the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and its application to susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc 5, 1460–1469 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2010.110

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2010.110

This article is cited by

-

High-throughput analysis of lipidomic phenotypes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by coupling in situ 96-well cultivation and HILIC-ion mobility-mass spectrometry

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2023)

-

Extracytoplasmic sigma factor AlgU contributes to fitness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PGPR2 during corn root colonization

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2022)

-

Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in heterosexual men with reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone, first report in Thailand

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa toward higher fitness under standard laboratory conditions

The ISME Journal (2021)

-

Novel colistin-EDTA combination for successful eradication of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae catheter-related biofilm infections

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.