Abstract

White matter disruption has been repeatedly documented in schizophrenia consistent with microstructural disorganization (reduced fractional anisotropy (FA)) and axonal dysfunction (reduced N-acetylaspartate NAAc). However, the clinical significance of these abnormalities is poorly understood. Diffusion tensor and proton spectroscopic imaging where used to assess FA, axial diffusivity and radial diffusivity (RD), and supra-ventricular white matter NAAc, respectively, in 64 schizophrenia and 64 healthy subjects. Schizophrenia patients had reduced FA across several regions, with additional regions where FA correlated positively with positive symptoms severity. These regions included genu, body and splenium of corpus callosum, anterior and superior corona radiata, superior longitudinal and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi, and internal capsule. The FA/symptoms relationships corresponded with opposite correlations between RD and positive symptoms. The schizophrenia group (SP group) had progressively reduced NAAc with age, and NAAc correlated negatively with positive symptoms. Cognition correlated positively with both FA and NAAc in controls, whereas in the SP group it had a negative correlation with NAAc and no significant relationship with FA. Antipsychotic dose did not account for the results. Correlates of psychosis, cognitive and negative symptoms can be found in white matter. The significant correlations between positive symptoms in schizophrenia and diffusion and NAAc measures suggest decreased axonal density with increased glial cells and higher myelination in this subpopulation. A separate set of abnormal relationships between cognition and FA/RD, as well as with NAAc, converge to suggest that in schizophrenia, white matter microstructure supports the two core illness domains: psychosis and cognitive/negative symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

White matter (WM) abnormalities have been described in schizophrenia (SP) using morphometric, post mortem and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI; Hoistad et al, 2009). DTI studies find reduced fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of water diffusivity consistent with myelination and/or axonal coherence abnormalities (Skudlarski et al, 2013). However, the topographical organization, time of development, diagnostic specificity, and neurobiological mechanism underlying the FA reductions are not clear. In addition, the psychopathological and cognitive correlates of FA in SP remain unknown.

More recently, it has been reported that in SP, higher FA values may correlate with psychotic symptom severity (ie hallucinations and delusions (Hubl et al, 2004)). This counterintuitive relationship (in the face of reduced FA) has been interpreted as increased structural connectivity among regions involved in language production and monitoring, with resultant misattribution of inner speech, leading to psychotic symptoms (Shergill et al, 2007). However, these studies involved small samples (10–34) and were vulnerable to selection bias of WM regions. Others have not found this correlation (Skelly et al, 2008).

We have examined the relationships between psychopathology and cognition with two measures of WM physiology (diffusion and axonal integrity) in the largest sample of SP and healthy control (HC) subjects. DTI was analyzed with an unbiased approach (Tract Based Spatial Statistics, TBSS (Smith et al, 2006)). Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (1H-MRSI) assessed N-acetylaspartate compounds (NAAc) in WM, a measure of axonal integrity. We hypothesized positive relationships between FA and positive symptoms. We also explored correlations between FA, radial and axial diffusivity (RD and AD, respectively), and cognitive measures, as well as with negative symptoms and between WM NAAc and cognition and psychopathology. Finally, we expected to detect FA (Hoistad et al, 2009) and NAAc (Kraguljac et al, 2012) reductions in SP.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Patients with SP were recruited from the University of New Mexico Hospitals and the Albuquerque Veterans-Affairs-Medical-Center. Inclusion criteria were: (i) DSM-IV-TR SP made through consensus by two research psychiatrists using the SCID-DSM-IV-TR, Patient-Version and (ii) clinically stable on the same antipsychotic medications >4 weeks. Exclusion criteria were: (i) diagnosis of neurological disorder; (ii) current substance-use disorder (except for nicotine); (iii) metallic implants; and (iv) claustrophobia. HC were excluded for any of the following: (i) any current DSM-IV-TR axis-I disorder (SCID-DSM-IV-TR Non-Patient-Version; (except current nicotine) or any past history of a disorder (except for substance use); and (ii) first-degree relative with psychotic disorder. The local IRB approved the study. Subjects provided informed consent and were paid.

Clinical and Neuropsychological Assessments

Subjects completed the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS; Buchanan et al, 2005). In patients, psychopathology was assessed with the Positive-and-Negative-Syndrome-Scale (PANSS; Kay et al, 1987). PANSS raters reached good inter-rater reliabilities (positive symptom ICC=0.86 and negative symptom ICC=0.64). Assessments were completed within 1 week of scanning.

MR Acquisition

A Siemens 3 T Tim-Trio with 12-channel-RF coil was used. An MPRAGE was initially acquired: 1.0 mm sagittal slices, 7° Flip angle, TR=2530 ms, TE1=1.64 ms, TE2=3.5 ms, TE3=5.36 ms, TE4=7.22 ms, TE5=9.08 ms, FOV was 256 × 256. The DTI was obtained in the axial direction along the AC-PC line, had 30 directions, b=800 s/mm2 and five interleaved measurements of b=0. The FOV was 256 × 256 mm with a 2 mm slice thickness, 72 slices, 128 × 128 matrix size, voxel size=8 mm3, TE=84 ms, TR=9000 ms, NEX=1, partial Fourier encoding of 3/4, and with a GRAPPA acceleration factor of 2 (6 min total).

1H-MRSI was performed with point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS). Briefly, PRESS with and without water pre-saturation were acquired (TE=40 ms, TR=1500 ms, slice thickness=15 mm, FOV=220 × 220 mm, circular k-space sampling (radius=24), 20 min. total). The nominal voxel size was 6.9 × 6.9 × 15 mm3 with effective volume of 2.4 cm3. The one 1H-MRSI slab was immediately above the lateral ventricles and parallel to AC-PC axis including portions of the medial frontal and parietal lobes (Gasparovic et al, 2006).

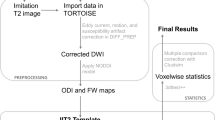

DTI Data Analysis

The analysis was based on FSL (available from: http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk). Preprocessing consisted of the following: (i) removal of gradient directions with signal dropouts owing to motion (subjects with >10% gradient directions removals were not included); (ii) motion and eddy current correction; and (iii) corrected gradient directions for any image rotation completed during the previous motion correction step. FA, RD and AD, scalar diffusion parameters, were calculated using DTIFIT. The FA image was normalized to MNI space with a nonlinear registration algorithm (FNIRT). A mean FA image was calculated from these spatially normalized images. The TBSS algorithm was then applied to the mean FA image to calculate a mean WM tract skeleton. The FA data of each subject was then projected onto the mean WM skeleton. Similar analyses were performed for RD and AD.

1H-MRSI Data Analysis

1H-MRSI data were analyzed using Linear-Combination-Model (Provencher, 1993). We automatically selected spectra with goodness-of-fit, as measured by Craemer-Rao-Lower-Bound of ⩽20 for N-acetylasparate plus NAAc, the metabolite of interest. These values were corrected for partial volume of gray matter (GM), WM and cerebrospinal fluid (using segmented T1 images) and relaxation effects, as outlined previously. Voxels with WM fraction (WM%÷(WM%+GM%))⩾66% were considered ‘white matter’ voxels. (‘gray matter voxels’ and other neuro-metabolite data will be included in a future report with the full sample). Finally, voxels were classified as right or left hemisphere and frontal or parietal based on their position relative to the central sulcus (see Gasparovic et al, 2006 for full description)

Statistical Analysis

FA

Statistical linear models were tested on the TBSS skeleton. Significance of model parameters with multiple comparison correction (p=0.05) was determined by threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE; Smith and Nichols, 2009) combined with 5000 non-parametric permutations (randomize, FSL). Fifty regions on the skeleton were labeled as per a WM atlas (Mori et al, 2008). The number of voxels and their mean FA reaching statistical significance were calculated for each of these skeleton regions. Group differences in FA, accounting for main and interactive effects of age was tested with the formula:

where k is indexed over subjects, FAk is the FA at a voxel for kth subject, HCk=1 for HC and SPk=1 for SP, and Agek is the subject’s age. The contrast α0–α1 was tested for the difference of FA between the two groups; α2 is the slope of FA dependence on age (the selection of 40 to center age does not affect any conclusions). The interaction term α3 examines different relationships for FA and age across the groups (α3 was not significant, whereas α2 was, hence we include age as a covariate for all further analyses).

The following model examined in SP the FA relationship with positive PANSS scores (α4) accounting for antipsychotic dosage, as olanzapine equivalents (OLZ; Gardner et al, 2010); represented by α5):

A similar analysis was done on negative PANSS scores.

Finally, the main effect of MATRICS overall score (α6) and its interaction with group (α7) was examined by the formula:

Similar analyses were performed for RD and AD.

NAAc

NAAc values from all WM voxels were the dependent variable for PROC-MIXED (SAS version-9) analyses, with diagnosis as the grouping factor and age. MATRICS overall score, PANSS scores and OLZ were also used as co-variates. Only significant interactions or main effects were followed with post hoc tests.

Results

Demographics

Ninety SP and 74 HCs were studied. However, 26 SP and 10 HCs were excluded because of DTI artifacts (no subjects had defined brain abnormalities). Hence, 64 SP and 64 HCs were included (Supplementary Table). Of these, 64 SP and 61 HCs had 1H-MRSI data. There were no significant differences between the groups in: age or socioeconomic status (SES) of the family of origin. The SP group had a lower proportion of females (χ2=2.9, p=0.09), a higher proportion of smokers (χ2=4.3, p=0.04) and worse personal SES (χ2=25.7, p<0.0001). Vascular risk factors (Jonckheere–Terpstra test, p=0.02) and history of cannabis (χ2=7.9, p=0.0005) and stimulant use (χ2=5.4, p=0.02) were greater in the SP group. Excluded subjects did not differ in demographic, clinical, or neuropsychological measures compared with the subjects studied (p-values>0.05).

Group Differences in Diffusion

SPs had lower FA across multiple brain regions compared to HCs at p=0.05 (TFCE; α0–α1 is significantly positive in equation (1), see Figure 1). The distribution of significant voxels is shown in the Table 1 (column B). Reduced FA was found in anterior corona radiata, genu and body of the corpus callosum, superior corona radiata, right anterior limb of the internal capsule, and superior longitudinal fasciculus. There were no regions where FA was significantly higher in SPs. Including gender and smoking status did not affect these differences. FA and AD decreased whereas RD increased with age but there were no interactions with diagnosis and AD and RD were not found to be significantly different between the two groups.

Spatial distribution of voxels with significantly reduced FA (in red) in schizophrenia (n=64) compared with healthy controls (n=64) accounting for age. Various colors identify some fasciculi (Mori et al, 2008).

Diffusion and Symptomatology

The spatial distribution of significant correlations between FA and positive PANSS scores in SPs, based on equation (2) is shown in Figure 2a. FA had positive correlations with positive symptoms across multiple regions, whereas OLZ and negative symptoms had no effect. The Table 1 (column C) shows the distribution of significant voxels, several of which overlap with those having a group difference. They included: genu, body and splenium of corpus callosum, anterior, superior, and posterior corona radiata, superior longitudinal and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi, and the internal capsule. FA averaged over these significant regions positively correlated with positive symptoms (r62=0.59, p<0.0001; Figure 2b). RD had negative correlations with positive symptoms through many of the same regions as FA (r62=0.57, p<0.0001; Figure 2c) wheras AD had no such relationships. There were no correlations between hallucinations severity and FA or RD across any regions.

(a) Spatial distribution of voxels (in red) with a significant relationship between FA and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. (b) Scatter plot of mean FA (from 2a) vs positive symptoms in schizophrenia group (r62=0.59, p<0.0001; n=64). (c) Scatter plot of the mean RD values of voxels with a significant correlation with positive symptoms in the schizophrenia group (r63=0.57, p<0.0001; N=64).

Diffusion and Cognition

Over many voxels the MATRICS total score and group interacted in relationship to FA (α7 with P<0.05 from equation (3); see Figure 3a and Table 1, column D). A similar interaction was found for RD but not for AD. In the regions of significant interaction, an analysis for mean FA showed a positive correlation for HCs (r62=0.54, p<0.0001) and a negative correlation for SPs (r62=−0.27, p=0.03; Figure 3b). Similarly, in regions with MATRICS and group interaction for RD, there was a corresponding negative RD relationship with MATRICS for HCs (r62=−0.51, p<0.0001) and a positive correlation for SPs (r62=0.28, p=0.03; Figure 3c). Because of the presence of interaction, separate analyses for each group demonstrated a positive correlation between FA and MATRICS scores for the HCs, but no relationships in the SPs, across many voxels after multiple comparison correction; the Table 1 (column E) shows the spatial distribution of the significant voxels for HCs. A corresponding pattern was identified for RD, but not for AD.

(a) Spatial distribution of voxels (in red) with a significant interaction between MATRICS total score and group (schizophrenia and control subjects) as these relate to FA. (b) Scatter plot of mean FA vs MATRICS total score (from a) in the healthy control (r62=0.54, p<0.0001; n=64) and the schizophrenia (r62=−0.27, p=0.03; n=64) groups. (c) Scatter plot of the mean RD values of voxels with a significant interaction between MATRICS total score and group in the healthy control (r62=−0.51, p<0.0001; n=64) and the schizophrenia (r62=0.28, p=0.03; n=64) groups.

Next, in order to further understand the relationship between FA and cognition in SP, we explored regions where: (i) the MATRICS by group interaction (α7) was significant; and (ii) FA was not significantly correlated with MATRICS scores in the HCs. These regions more directly test a negative correlation between FA and MATRICS scores in SPs. After restricting the mask for multiple comparisons to the regions defined by conditions (i) and (ii), we found a significant negative correlation only in the body of the corpus callosum (r62=−0.42, p=0.0005); the Table 1 (column F) provides the distribution of these voxels.

To examine if the same regions would exhibit the principal findings described above, we tested voxels where: (i) FA was lower in SPs; and (ii) FA was correlated with positive PANSS scores; and (iii) FA correlated with MATRICS scores in HCs. The Table 1 (column G) provides their spatial distribution. These voxels are primarily in the genu and the body of the corpus callosum, and both sides of the anterior and the superior corona radiata.

Finally, adjusting for psychotropic exposure, history of cannabis/stimulant use, or vascular risks did not significantly affect the FA and RD group differences, or their relationships with cognition across groups, or the correlations with symptoms in the SP group (all p-values<0.05).

NAAc Differences and Correlations

SPs had a greater reduction of NAAc with age than HCs (F1,121=4.31, p=0.04). However, the NAAc difference between the oldest (median split >36 years) SP and HC subgroups was not significant (F1,59=1.94, p=0.17). Controlling for age, negative symptoms positively correlated with global NAAc (F1,60=51.9, p<0.0001). This relationship was apparent in both WM frontal regions (left: F1,62=31.7, p<0.0001 and right: F1,62=10.7, p=0.002) and in parietal regions (left: F1,62=11.4, p=0.001 and right: F1,62=4.5, p=0.04). Controlling for age, positive symptoms negatively correlated with NAAc (F1,60=34.3, p<0.0001). This relationship was apparent in both WM frontal regions (left: F1,61=24.0, p<0.0001 and right: F1,61=24.5, p<0.0001) and in right parietal (F1,62=12.9, p=0.001) but not left (F1,121=2.2, p=0.15) regions. There were no relationships between NAAc and OLZ (F1,60=1.2, p=0.28).

Group interacted with MATRICS score and age (F2,113=3.6, p=0.03). However, regardless of age, HCs had the expected positive relationship between NAAc and MATRICS (Deary et al, 2006); Schmithorst et al, 2005) whereas SP had a negative relationship (F1,113=72.8, p<0.0001; Figure 4). This relationship was apparent in both WM parietal regions (left: F1,121=23.3, p<0.0001 and right: F1,121=38.7, p<0.0001) and in the right frontal (F1,121=8.9, p=0.003) but not the left frontal (F1,121=0.56, p=0.46) regions. In addition, MATRICS was negatively correlated with negative symptoms in the SPs (r63=−0.34, p=0.007), but not with positive symptoms (r63=0.13, p=0.30). Negative and positive symptoms were not correlated (r63=0.06, p=0.64). Finally, adjusting for psychotropic exposure, history of cannabis/stimulant use or vascular risks did not significantly change the relationships between NAAc and age or cognition across groups or the correlations with symptoms in the SP group (all p-values<0.05, except for the group by age interaction with vascular risk, p=0.06, and with stimulant use, p=0.17).

Scatter plot of mean white matter NAAc vs MATRICS total score in the healthy control (r60=0.22, p=0.09; n=61) and the schizophrenia (r63=−0.31, p=0.01; n=64) groups.

Discussion

Our results are indeed paradoxical. In SP we confirmed FA reductions in several WM regions, remarkably similar to the ones described in a recent large study with TBSS (Skudlarski et al, 2013; however we did not find occipital reductions). Greater reduction of WM NAAc with age in SP was additionally detected, consistent with our previous study (Bustillo et al, 2011). However, we also found that these two measures of WM physiology, for the most part correlated counter-intuitively with the core symptom domains of SP: the higher the FA, the greater the positive symptoms, and the higher NAAc, the worse negative symptoms and cognitive function. Only positive symptom severity correlated negatively with NAAc. The spatial distribution of the FA/psychosis association was remarkable because it involved most of the analyzed FA skeleton (47 of 50 regions, though not most voxels in these regions). The NAAc/cognition relationship was present bilaterally in parietal WM, as well as in the right frontal region. Finally, both FA and NAAc had the expected positive correlations with cognition in HCs (Deary et al, 2006), supporting the validity of these measurements.

Several studies have reported positive associations between psychotic symptoms and FA in SP using region-of-interest, voxel-based (VB), TBSS and tractography approaches, with samples between 10 (Mulert et al, 2012) and 34 (Cheung et al, 2011). The majority of them also reported reduced FA (Choi et al, 2011; Hubl et al, 2004; Lee et al, 2013; Seok et al, 2007; Shergill et al, 2007; Szeszko et al, 2012; Whitford et al, 2010). The positive correlations with psychotic symptoms have been reported in several structures including left hemisphere (Hubl et al, 2004), left (Seok et al, 2007) and bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculus (Shergill et al, 2007), left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (Szeszko et al, 2008), anterior commissure (Choi et al, 2011), corpus callosum (Mulert et al, 2012; Whitford et al, 2010), and other regions (Cheung et al, 2011; Lee et al, 2013). However, others have reported negative correlations between FA and psychotic symptoms (Kitis et al, 2012; Skelly et al, 2008); (Boos et al, 2013; Catani et al, 2011; Cui et al, 2011). An important negative finding with VB is the study in mostly drug-naive first episode patients (SP, N=122; Wang et al, 2013). Finally, most 1H-MRS studies have not reported significant NAAc correlations with symptoms (Kraguljac et al, 2012). However, some have found a negative relationship between WM NAAc with positive and with negative symptoms (He et al, 2012).

Our study is generally consistent with the majority of this literature in chronically ill patients. However, the results are striking for the much broader spatial distribution of the FA/positive symptom relationship. This included several of the regions previously reported as potentially representative of networks involving inner speech (eg: superior longitudinal, inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi), as well as others not typically thought to be involved in language (eg: corticospinal tract, cerebral peduncles; see the Table 1, column B). Consistent with the previous literature in SPs, none of the regions that had this relationship were higher in FA than HCs.

Differences in sample characteristics and DTI and 1H-MRSI methodology may account for differences with the existing literature. Our sample was larger than most previous studies, except for two. One (Boos et al, 2013) utilized tractography, acquired at 1.5 T and found no FA reductions. Perhaps the averaging of FA along each tract, reduced the sensitivity in this study to detect the expected FA reduction in SP, as well as positive relationships with psychotic symptoms. The other (Wang et al, 2013) studied mostly drug-naive patients with VB. Our subjects were chronically ill but clinically stable, perhaps exhibiting more trait-like positive symptoms. Regarding methods, we used higher field strength providing greater signal to noise (predominantly in the periphery) than most previous studies. Also, use of TBSS provided broad unbiased spatial coverage with reduced partial volume effect (Smith et al, 2006), a limitation of VB.

Three studies have acquired DTI and 1H-MRS (single-voxel) in schizophrenia, in chronic patients and with smaller samples. Two studies (Tang et al, 2007; Steel et al, 2001) reported decreased WM NAAc. Tang et al, (2007), and Rowland et al, (2009) found reduced FA. None found relationships with symptoms or cognition. Finally, though the metanalysis found reduced NAAc in several WM regions (Steen et al, 2005), differences in the centrum semiovale were smaller, somewhat consistent with our negative findings.

The broadly distributed positive correlations between FA and cognition found in the HCs are consistent with previous literature (Deary et al, 2006; Schmithorst et al, 2005). This pattern was clearly lost in the schizophrenia group and even followed an inverse correlation in the corpus callosum, suggesting that, as with positive symptoms, FA values closer to the normal range correspond to greater pathology. The reported relationship between FA and cognition in schizophrenia has tended to be positive mainly early in the illness (Wang et al, 2013; Perez-Iglesias et al, 2010). However, our 1H-MRSI results clearly converge with the FA findings: NAAc correlated positively in HC but negatively in the schizophrenia group, supporting the validity of results in this sample.

What is the meaning of this counter-intuitive relationship of FA increasing with symptoms? FA is a composite measure related to myelination and axonal coherence, including both normal alignment and complexity (number of crossing fibers; however, the relationship between FA and myelin has been questioned; Sen and Basser, 2005). In WM, NAAc is found almost exclusively in axons and its concentration indicates axonal density (Rae, 2014). In addition, schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder and different aspects and stages of the illness may affect FA and NAAc through separate and even opposing mechanisms. Furthermore, the effect of antipsychotic medication cannot be discounted (Wang et al, 2013; Reis Marques et al, 2014). A trait dysfunction in myelination may account for the primary reduction in FA in schizophrenia (as supported by post-mortem and genetic studies (Hoistad et al, 2009), but also by lower FA in unaffected family members (Skudlarski et al, 2013). However, we did not find RD group differences. Still, in the more psychotic patients, we see increased structural connectivity (higher FA) perhaps secondary to increased myelination (lower RD), with lower axonal density (reduced NAAc). We speculate that the underlying tissue changes may involve increased oligodendrocytes, which would account for both increased myelin and reduced axonal density. Regarding the chronology of presentation of the relationships between FA and psychosis in schizophrenia, we posit two alternative models.

In an Adaptive framework (model-1), chronically psychotic subjects may develop increased myelination across various tracts, like those involved in the generation and monitoring of inner speech (Shergill et al, 2007), but eventually distributed though-out many WM regions. Our findings involving bilateral regions like internal and external capsule, corona radiata and superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculi (Table 1 column C) are consistent with bilateral fronto-temporal cortical regions of increased functional connectivity in schizophrenia patients with hallucinations (Jardri et al, 2011).

Alternatively, in a Cohort framework (model-2), patients with already increased myelination in critical networks may be predisposed to more sustained positive symptoms. However, contrary to model-2, the largest study of drug-naive patients (Wang et al, 2013) found reduced FA but no relationship with positive symptoms.

SPs had absent relationships of FA with cognition and in parts of the corpus callosum there was a negative correlation. With NAAc, the relationships were clearly negative. Though cognition is normally supported by higher FA (perhaps because of optimal myelination and axonal coherence) and higher NAAc, in schizophrenia it may be further affected by other neurobiological variables which may lead to compensatory remodeling of WM tracts to support cognition later in the illness (model-1). We speculate of a selective reduction of the more aligned axons, leaving fewer (reduced NAAc) but mainly crossing fibers (reduced FA), in those more cognitively intact SPs. Regardless of mechanism, the positive correlation between FA and cognition found early in the illness in the largest sample to date (Wang et al, 2013), argues against model-2 and suggests an undetermined adaptive process resulting in a fundamental microstructural reorganization of WM latter in the illness.

The diffusion, relaxation, and neurochemical characteristics of WM in schizophrenia are complex. In chronically ill medicated patients, both increased water T2, as well as decreased NAA T2 were found (Du et al, 2012) suggestive of reduced macromolecules and abnormal intra-axonal milieu, respectively. A follow-up study reported decreased magnetization transfer, consistent with reduced myelin, but increased NAAc diffusion. Though both of these abnormalities could lead to reductions in FA, they did not correlate with each other, suggesting ‘independent mechanisms leading to myelin and axonal abnormalities’ (Du et al, 2013). In addition NAAc diffusion and T2 relaxation were not related (Du et al, 2013), further arguing for the complexity of WM microstructural changes in schizophrenia.

This study had several strengths, including unbiased assessment of WM with automated DTI and 1H-MRSI analytic tools, contrasts of FA, RD and AD, reliable symptom assessments, standardized cognitive battery and a large sample. However, limitations should be acknowledged. First, patients were chronically ill and treated with antipsychotic medications, which have been reported to increase (Reis Marques et al, 2014) and decrease (Wang et al, 2013) FA and perhaps confound the relationships we found. However, current antipsychotic dose did not account for our results. Long-term treatment studies assessing antipsychotic compliance in different stages of the illness are necessary. Second, TBSS does not measure FA along tracts associated with specific brain function. Although some tractography-based studies have found similar relationships with psychosis (Lee et al, 2013), others have not (Boos et al, 2013). Third, our DTI sequence was not cardiac-gated. Fourth, we did not assess length of substance-use history. Fifth, diffusion and NAAc measures were not spatially co-localized. Finally, the cross-sectional study design supports mainly the descriptive and not the causal interpretations.

In summary we report, in the context of broadly reduced FA but normal WM NAAc in SP, positive correlations between positive symptoms and FA, but negative ones between these symptoms and NAAc and RD, suggestive of increased myelination throughout multiple WM bundles among the most psychotic patients. A separate set of abnormal relationships between cognition and FA, as well as with NAAc, converge to suggest that a fundamentally different WM microstructure supports the two core illness domains: psychosis and cognitive/negative symptoms. In the context of the current literature, an adaptive process evolving later in the illness is most consistent with these findings. Future longitudinal studies examining the evolution of these relationships and their specificity to myelination, axonal coherence, and functional connectivity may shed light on the underlying neurobiology of persistent psychosis and cognitive deficits.

Funding and Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Boos HB, Mandl RC, van Haren NE, Cahn W, van Baal GC, Kahn RS et al (2013). Tract-based diffusion tensor imaging in patients with schizophrenia and their non-psychotic siblings. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23: 295–304.

Buchanan RW, Davis M, Goff D, Green MF, Keefe RS, Leon AC et al (2005). A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 31: 5–19.

Bustillo JR, Chen H, Gasparovic C, Mullins P, Caprihan A, Qualls C et al (2011). Glutamate as a marker of cognitive function in schizophrenia: a proton spectroscopic imaging study at 4 Tesla. Biol Psychiatry 69: 19–27.

Catani M, Craig MC, Forkel SJ, Kanaan R, Picchioni M, Toulopoulou T et al (2011). Altered integrity of perisylvian language pathways in schizophrenia: relationship to auditory hallucinations. Biol Psychiatry 70: 1143–1150.

Cheung V, Chiu CP, Law CW, Cheung C, Hui CL, Chan KK et al (2011). Positive symptoms and white matter microstructure in never-medicated first episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med 41: 1709–1719.

Choi H, Kubicki M, Whitford TJ, Alvarado JL, Terry DP, Niznikiewicz M et al (2011). Diffusion tensor imaging of anterior commissural fibers in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 130: 78–85.

Cui L, Chen Z, Deng W, Huang X, Li M, Ma X et al (2011). Assessment of white matter abnormalities in paranoid schizophrenia and bipolar mania patients. Psychiatry Res 194: 347–353.

Deary IJ, Bastin ME, Pattie A, Clayden JD, Whalley LJ, Starr JM et al (2006). White matter integrity and cognition in childhood and old age. Neurology 66: 505–512.

Du F, Cooper A, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF, Ongur D (2012). Water and metabolite transverse T2 relaxation time abnormalities in the white matter in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 137: 241–245.

Du F, Cooper AJ, Thida T, Shinn AK, Cohen BM, Ongur D (2013). Myelin and axon abnormalities in schizophrenia measured with magnetic resonance imaging techniques. Biol Psychiatry 74: 451–457.

Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O'Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ (2010). International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry 167: 686–693.

Gasparovic C, Song T, Devier D, Bockholt HJ, Caprihan A, Mullins PG et al (2006). Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med 55: 1219–1226.

He ZL, Deng W, Li ML, Chen ZF, Collier DA, Ma X et al (2012). Detection of metabolites in the white matter of frontal lobes and hippocampus with proton in first-episode treatment-naive schizophrenia patients. Early Interv Psychiatry 6: 166–175.

Hoistad M, Segal D, Takahashi N, Sakurai T, Buxbaum JD, Hof PR (2009). Linking white and grey matter in schizophrenia: oligodendrocyte and neuron pathology in the prefrontal cortex. Front Neuroanat 3: 9.

Hubl D, Koenig T, Strik W, Federspiel A, Kreis R, Boesch C et al (2004). Pathways that make voices: white matter changes in auditory hallucinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61: 658–668.

Jardri R, Pouchet A, Pins D, Thomas P (2011). Cortical activations during auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 168: 73–81.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1: 261–276.

Kitis O, Ozalay O, Zengin EB, Haznedaroglu D, Eker MC, Yalvac D et al (2012). Reduced left uncinate fasciculus fractional anisotropy in deficit schizophrenia but not in non-deficit schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 66: 34–43.

Kraguljac NV, Reid M, White D, Jones R, den Hollander J, Lowman D et al (2012). Neurometabolites in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 203: 111–125.

Lee SH, Kubicki M, Asami T, Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Mesholam-Gately RI et al (2013). Extensive white matter abnormalities in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study. Schizophr Res 143: 231–238.

Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, Jiang L, Li X, Akhter K et al (2008). Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. Neuroimage 40: 570–582.

Mulert C, Kirsch V, Whitford TJ, Alvarado J, Pelavin P, McCarley RW et al (2012). Hearing voices: a role of interhemispheric auditory connectivity? World J Biol Psychiatry 13: 153–158.

Perez-Iglesias R, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Barker GJ, McGuire PK, Roiz-Santianez R, Mata I et al (2010). White matter defects in first episode psychosis patients: a voxelwise analysis of diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 49: 199–204.

Provencher SW (1993). Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med 30: 672–679.

Rae CD (2014). A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra. Neurochem Res 39: 1–36.

Reis Marques T, Taylor H, Chaddock C, Dell'acqua F, Handley R, Reinders AA et al (2014). White matter integrity as a predictor of response to treatment in first episode psychosis. Brain 137: 172–182.

Rowland LM, Spieker EA, Francis A, Barker PB, Carpenter WT, Buchanan RW (2009). White matter alterations in deficit schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 34: 1514–1522.

Schmithorst VJ, Wilke M, Dardzinski BJ, Holland SK (2005). Cognitive functions correlate with white matter architecture in a normal pediatric population: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 26: 139–147.

Sen PN, Basser PJ (2005). Modeling diffusion in white matter in the brain: a composite porous medium. Magn Reson Imaging 23: 215–220.

Seok JH, Park HJ, Chun JW, Lee SK, Cho HS, Kwon JS et al (2007). White matter abnormalities associated with auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a combined study of voxel-based analyses of diffusion tensor imaging and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Res 156: 93–104.

Shergill SS, Kanaan RA, Chitnis XA, O'Daly O, Jones DK, Frangou S et al (2007). A diffusion tensor imaging study of fasciculi in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 164: 467–473.

Skelly LR, Calhoun V, Meda SA, Kim J, Mathalon DH, Pearlson GD (2008). Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia: relationship to symptoms. Schizophr Res 98: 157–162.

Skudlarski P, Schretlen DJ, Thaker GK, Stevens MC, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA et al (2013). Diffusion tensor imaging white matter endophenotypes in patients with schizophrenia or psychotic bipolar disorder and their relatives. Am J Psychiatry 170: 886–898.

Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE et al (2006). Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31: 1487–1505.

Smith SM, Nichols TE (2009). Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44: 83–98.

Steel RM, Bastin ME, McConnell S, Marshall I, Cunningham-Owens DG, Lawrie SM et al (2001). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) in schizophrenic subjects and normal controls. Psychiatry Res 106: 161–170.

Steen RG, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA (2005). Measurement of brain metabolites by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 1949–1962.

Szeszko PR, Narr KL, Phillips OR, McCormack J, Sevy S, Gunduz-Bruce H et al (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging predictors of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 38: 569–578.

Szeszko PR, Robinson DG, Ashtari M, Vogel J, Betensky J, Sevy S et al (2008). Clinical and neuropsychological correlates of white matter abnormalities in recent onset schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 976–984.

Tang CY, Friedman J, Shungu D, Chang L, Ernst T, Stewart D et al (2007). Correlations between diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) in schizophrenic patients and normal controls. BMC Psychiatry 7: 25.

Wang Q, Cheung C, Deng W, Li M, Huang C, Ma X et al (2013). Fronto-parietal white matter microstructural deficits are linked to performance IQ in a first-episode schizophrenia Han Chinese sample. Psychol Med 43: 2047–2056.

Wang Q, Cheung C, Deng W, Li M, Huang C, Ma X et al (2013). White-matter microstructure in previously drug-naive patients with schizophrenia after 6 weeks of treatment. Psychol Med 43: 2301–2309.

Whitford TJ, Kubicki M, Schneiderman JS, O'Donnell LJ, King R, Alvarado JL et al (2010). Corpus callosum abnormalities and their association with psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 68: 70–77.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIMH R01MH084898 to JRB, NIMH 2R01MH065304 and VACSR&D IIR-04-212-3 to JC and 1 P20 RR021938-01A1 and DHHS/NIH/NCRR 3 UL1 RR031977-02S2. JRB received honoraria for advisory board consulting from the Otsuka America Pharmaceutical in 2013. We are grateful to Patrick Gallegos and Ashley Jaramillo, employees of the UNM Department of Psychiatry, and to Diana South and Cathy Smith, MRN employees, for their contributions with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caprihan, A., Jones, T., Chen, H. et al. The Paradoxical Relationship between White Matter, Psychopathology and Cognition in Schizophrenia: A Diffusion Tensor and Proton Spectroscopic Imaging Study. Neuropsychopharmacol 40, 2248–2257 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.72

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.72

This article is cited by

-

Reduced structural integrity of the uncinate fasciculus in incarcerated women scoring high on psychopathy

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2022)

-

Impaired cerebro-cerebellar white matter connectivity and its associations with cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia

npj Schizophrenia (2021)

-

Neurometabolic correlates of 6 and 16 weeks of treatment with risperidone in medication-naive first-episode psychosis patients

Translational Psychiatry (2020)

-

Ketamine modulates hippocampal neurochemistry and functional connectivity: a combined magnetic resonance spectroscopy and resting-state fMRI study in healthy volunteers

Molecular Psychiatry (2017)

-

Schizophrenia symptomatic associations with diffusion tensor imaging measured fractional anisotropy of brain: a meta-analysis

Neuroradiology (2017)